An exhibition of censored artwork in Nagoya city triggers a furious debate on artistic expression.

The artistic director of the Aichi Triennale 2019 had few illusions when he planned an exhibition called “After Freedom of Expression”. By choosing items that poked painfully at some of Japan’s most tender spots – war crimes, subservience to America and the status of the imperial family – Tsuda Daisuke wanted to “provoke discussion” on the health of freedom of expression in the country. But what followed, he says, was “beyond our expectations”.

In the three days after the exhibition opened on August 1st at the Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya, the organizers were besieged with hundreds of angry phone calls and emails. Protesters shouted at staff or poured liquid on the floor, threatening to burn the exhibition to the ground. One man, later arrested, faxed in a handwritten threat to firebomb the exhibits in the same week as an arson attack on a Kyoto animation studio that killed 36 people.

“It was very frightening,” recalls Iida Shihoko, the Triennale’s chief curator. What surprised her, she says, was that so many of the protesters were women. Though the center had planned for blowback by hiring extra staff, they were quickly overwhelmed. As public servants, custom dictated they had to give their names if callers requested and listen patiently to tirades that could stretch for over an hour. Many callers appeared to be reading from scripts – “the staff could hear the pages rustling,” says Tsuda.

Far from being a spontaneous eruption of public fury, this campaign appears to have been coordinated, says Iida. Callers had the same talking points, which echoed the rhetoric of conservative politicians, notably Kawamura Takashi, the mayor of Nagoya and a member of the ultra-right lobby group, Nippon Kaigi. Kawamura made a highly publicized visit to the exhibition, where he zeroed in on a statue of a Korean “comfort woman” by the husband-and-wife sculptor team Kim Seo kyung and Eun sung. Officially called “Statue of Peace,” the statue, Kawamura intoned, “tramples on the feelings of the Japanese people” and shouldn’t be supported with taxpayers money (税金を使ってやるべきものではない). His intervention seemed to egg the protesters on. On August 3rd, Tsuda and Omura Hideaki, the governor of Aichi pulled the plug, citing public-safety issues.

Divorced from its context, the reaction to the statue, showing a beatific girl sitting beside an empty seat (so designed to allow visitors to sit eye-level with her) seems misplaced, even bizarre. But the controversy has less to do with the exhibit’s artistic merits than its ability to trigger well-worn political responses. “We’re not talking about art here, in the sense of artworks and their meaning or effect,” says Ayelet Zohar, an associate professor of art history at Tel Aviv University who is following the controversy. “We know what they signify, we do not care about their actual quality…It is about this specific signifier and what it does to politicians who understand very little about art and its subtleties, but can recognize a specific symbol when confronted with it.”

Kawamura is part of a political movement in Japan that regards the mainstream Western narrative of that nation’s war in Asia in the 1930s and 1940s as self-debasing and masochistic. In February 2012, he said the 1937 Nanjing Massacre never happened (a snub to the four former Japanese prime ministers who have made pilgrimages of atonement to the Chinese city – most recently Fukuda Yasuo). The movement’s minions leap into action over any suggestion that Asian women were pressed into sexual servitude by Japan’s wartime army dismissing an official Japanese apology and reparations program that says otherwise. The women were prostitutes, not sex slaves, they say, and the refusal of South Korea and China to put the issue behind them purposely stokes anti-Japanese feeling.

Despite a “final and irrevocable” deal between Japan and South Korea to end the dispute in 2015, the issue continues to poison bilateral ties. South Korea triggered a major row by scrapping a fund partly set up by Japan to compensate the surviving comfort women. A ruling last year in South Korea’s Supreme Court on Japan’s use of wartime conscript labour rubbed more salt on raw diplomatic wounds. The court ordered Nippon Steel and Sumitomo Metal Corp. to compensate four Koreans. Japan insists that all compensation claims were settled in the 1965 treaty that established diplomatic ties between the two nations. But resentment at Japan’s colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula from 1910-1945 still runs deep. At least a dozen similar suits have been filed against Japanese companies.

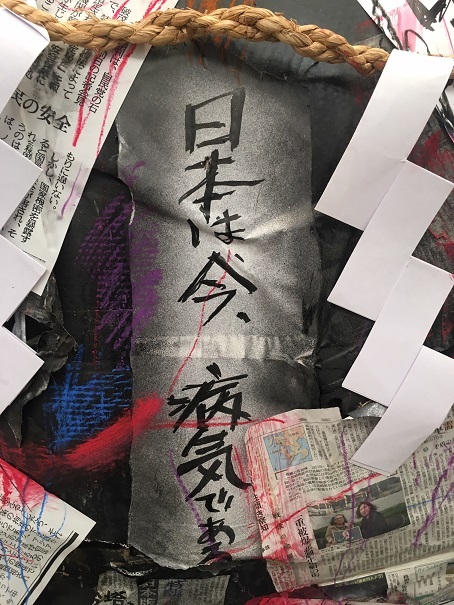

Arguably, the statue is among the more anodyne exhibits in a show defined by transgression. Nakagaki Katsuhisa’s “Portrait of the Period – Endangered Species idiot Japonica,” a dome-like installation, contemptuously lambasts the Japan-US military alliance. Koizumi Meiro’s Air#1, a portrait of the Imperial Family with all its members erased, nods to the ghostly space they occupy in the collective Japanese unconscious. Shimada Yoshiko’s twin portrait of the Showa Emperor with his face scratched out, then burned, also infuriated nationalists. All have previously run afoul of timorous curators. Shimada’s portraits, for example, which she created to “raise questions about the taboo” against the use of the emperor’s image, were returned by Toyama Modern Art Museum in 1993 (see here). The point of Aichi, said Tsuda, was to drag such pieces out of dusty warehouses and back into the public sphere – the Japanese title of the exhibition Hyōgen no jiyū: sono go – implies it was a second chance to view them.

|

|

In one sense, the reaction by the Japanese establishment bore out the worst fears of the Aichi curatorial team and seemed to confirm the old dictum that censorship reflects a society’s lack of confidence in itself. Okamoto Yuka, a member of the Freedom of Expression Organizing Committee, called the shutdown an act of “artistic violence” and blamed not just the shifting political climate under Prime Minister Abe Shinzo but a worldwide clampdown on freedom of expression. The Japanese government’s response was mealy-mouthed at best. Suga Yoshihide, the chief cabinet secretary, called the threats against the exhibit wrong “generally speaking”. A month later, the Agency for Cultural Affairs pulled Yen 78 million in subsidies for the Triennale because of “inappropriate procedural matters.” Education Minister Hagiuda Koichi, who is in charge of the agency, denied he was in effect telling the rightwing mob that violent threats work. The decision to terminate the funding was based solely on “whether the event could be properly managed and organized,” he said, to widespread skepticism.

Yet, the shutdown also inadvertently helped answer Tsuda’s call for a wider audit on the health of artistic freedom in Japan. Angry debate spilled out into public view. Omura Hideaki, the governor of Aichi Prefecture, openly criticized Kawamura, calling his demand that the exhibition be closed “unconstitutional” and pledging to legally fight the subsidy withdrawal (The prefecture is paying roughly half the Yen 1.2 billion cost of the Triennale). Dozens of artists in Japan, South Korea and around the world boycotted the event in solidarity over the decision to remove the offending material. Some spoke at a forum, organized by the prefecture to discuss the row on October 5/6th. (I was a speaker at this event.) “Censorship thrives on fear and insecurity and silence is its accomplice,” said Mexican artist Monica Mayer. She advised the organizers to prepare “offensive strategies” against attempts at further suppression.

These strategies were in place when the show reopened for a week on October 8th. Phone staff rotated every two hours to avoid over-exposure to toxic callers, and they were allowed to hang up after 10 minutes. Metal detectors were introduced at the entrance. The number of visitors was limited by a lottery system for a guided tour, complete with lengthy exposition on each exhibit. Photography was restricted and posting snaps on social media was banned. Still, the protests continued: a total of 10,000 often abusive phone calls, faxes and emails by the week of October 9th. Some callers threatened to film staff and put the videos online. Kawamura, meanwhile, announced the city was refusing to pay its share of 33.8m for hosting the event.

At least the tactical reopening answered criticism that Tsuda and the organizers were in over their head in August when they decided to poke Kawamura and his ilk in the eye. Tsuda acknowledged that the exhibition was “extremely challenging” in a “society rife with intolerance” towards different opinions and attitudes. “It is precisely because of the value we set on freedom of expression that we worked so hard to overcome numerous difficulties and realize this exhibition,” he said. The row comes roughly a decade after similar controversy over the documentary “Yasukuni”, directed by Li Ying (with the help of Yen 7.5 million in funding from the Japan Arts Council). More recently, “Shusenjo,” a crowd-funded documentary on the comfort women issue, directed by Miki Dezaki has also been violently threatened. The result in both cases was that many more people have seen these films than if their critics had gone instead to the local pub for a moan with their friends. It’s unclear if the same will apply in this case. Once the exhibition ends on October 14, the censored art may be returned to storage, waiting for a curator brave enough to risk the consequences of another public viewing.