Introduction

The material introduced here is a re-working of a chapter from my monograph, Dangerous Memory in Nagasaki: Prayers, Protests and Catholic Survivor Narratives, Routledge (2019), which discusses the symbolism around water and a ‘cry for water’ in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. Dangerous Memory in Nagasaki is a collective biography of twelve survivors of the Nagasaki atomic bombing, including nine Catholic survivors in which I employ a ‘political theology’ as framework to interpret the survivor narratives, showing that their memory upholds the historiography of Nagasaki as distinctive from Hiroshima. Survivor testimony subtly subverts the notion that the atomic bombings made Japan a victim, as Catholics were already victims of prejudice and persecutions carried out by the magistrate on behalf of the Tokugawa and Meiji authorities. Their memory is also dangerous to dominant Catholic narratives which argue that the atomic bomb could be understood as providential, and I argue in the book that survivors are angry, dispelling a common perception that Nagasaki Catholics show passivity, exhibiting no sense of resistance, and therefore lack agency.

The book initially introduces the religious and sociological elements of the ‘fissured’ nature of Nagasaki, the survivors themselves and the ‘dangerous’ memory of the bodies many encountered in the hours and days after the atomic bombing. I explain how the idea of a providential atomic bomb was initially compelling for this community, but also caused troubling silences. Many Catholics, including a number of the interviewees discussed in this book did not speak for over fifty years about their memory. There has been a gradual increase in discussing Catholic memory of the atomic bombing since Pope John Paul II’s visit to Nagasaki in 1981 as survivors such as those discussed in my book have become more ready to participate in peace-activities and openly protest the bombing. An essential part of this protest has been participating as kataribe, or valued storytellers who narrate their memory of the atomic bomb. The chapter reproduced here falls into the second section of the book, part of the discussion of how symbolic memory and reinterpreting the bomb from the specific region of Urakami, north of the city centre, and location of Ground Zero, is made meaningful by considering symbols such as Urakami Cathedral which was destroyed, Mary statues of the Mother of Christ, and plaintive ‘cries for water’ in the atomic field. Urakami is the Catholic region around Ground Zero and a place of return for the exilees after the persecution of the 1870s.

The final section of the book engages with the political nature of the testimony of survivors, describing hope carried forward by survivors who demonstrate a resilience and tenacity by their speech and narrative, despite an extended period of prejudice and social exclusion in an irradiated and overlooked region of the city. The Catholic kataribe demonstrate a readiness to protest out of their lament and anger within this collective biography.

I engage in this chapter in a discussion of two atomic bomb survivors’ memory of a ‘cry for water’ they heard after the bombing and how the Catholics’ narratives of persecution from the nineteenth century echo this cry, through the recorded diary of the great-grandmother of an interviewee, whose name was Kataoka Sada. The geographical setting is essential to this writing, as the Urakami river in the valley is where many of the dying cried for water and then were laid to rest, as depicted in Miyake Reiko’s narrative the day after the bombing.

Echoes of the past on the atomic field: Water please!

I heard the [boy’s] voice saying, ‘Brother, mizu wo chōdai – water please!’ Nakamura Kazutoshi, 2016.

My God, why have you forsaken me? Jesus, Mark 15: 34.

From the sacred images of Mary to the broken-down cathedral, let us relocate our interpretive discussion to the Urakami river (Figure 1), where the cry for water – as identified by Miyake Reiko and Nakamura Kazutoshi – was indelible in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. This cry is dangerous, troubling memory, a motif identified secondarily in the previous persecutions, by Kataoka Chizuko’s great-grandmother, Sada. Miyake and Nakamura are haunted by their memory of this sad cry, although we know water as an elemental symbol of life. Water in both the atomic and persecution narrative was dangerous and this cry reflected the peoples’ utter betrayal and dehumanisation. Silenced cries for water are reanimated in this chapter by the two kataribe, who heard it and remember. They act as witnesses, protesting their own impotence in the face of oppressive and unfair treatment.

|

Figure 1. A tributary of Urakami River on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki photograph, used with permission, Fiona McCandless, 25 January 2019. |

Introduction

A ‘cry for water’ rang out again and again in the ‘atomic field’ after the bombing. Such a cry, abruptly silenced by death, is a common theme within many testimonies from both Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as the title of a book published back in 1972 suggests.1 The book, translated into English, was entitled, ‘Give me Water: Testimonies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’. Interviewees Miyake Reiko and Nakamura Kazutoshi also heard this call, which they could not forget.

Memoirs and recollections in literature present atomic bomb victims pleading for water and dying as soon as they could drink. The cry for water in the atomic wasteland: ‘mizu wo!’ – is a desperate cry for help by the victims, to ‘somebody’, to God or the gods. As Nakamura and Miyake remember the cry for water they identify an intrinsic part of ‘dangerous’ memory, ‘listening’ to those who were literally silenced. The cries for water haunt not only the atomic narrative, but also the public history about persecutions, namely in the experiences of the great-grandmother, Sada, of hibakusha (bomb-survivor) interviewee Kataoka Chizuko. Thus, here, I compare three instances of the cry for water, including the narrative of the persecution, each remembered from Urakami.

People cried out and died in the Urakami River after the bombing but water is simultaneously a symbol of life, replenishment and spiritual well being. An idyllic photograph depicts a tributary of the Urakami river which flows through the Peace Park, as a child plays on the 70th anniversary of the bombing (Figure 1). Today, water flows adjacent to the hypocenter memorial in the Peace Park and a sculpted basin of water is found at the Peace Memorial Hall at the top of the hill, ‘containing the water that the victims of the atomic bombing so desperately craved’.2

Water is an elemental symbol of a flourishing environment. Juxtaposed narratives of desecration and purification recall the bodies of the dead clogging waterways and harmonising with the ecosystem, just as bodies melded with Urakami’s soil in the wake of the bomb.

Mary! Give me water!

The cry for water in both atomic and persecution narratives questions God’s goodness, endangering belief. A literary group wrote a poem in 1982 reflecting upon the ‘cry for water’ with a Catholic-oriented perspective. The Christian faithful call for compassionate ‘Mary of Urakami’ to rise from her rest and to act, writing in the first line ‘Virgin Mary of Urakami, I beg of you, Answer me now…’ The poem imitates the literary form of biblical Psalms which pursue justice, calling for God to pass judgement on those who unleashed the bomb: ‘…Are you watching, God?… Pass your judgement…’ In another stanza, the group reiterates the cry for water: ‘…Water! Give me water! … Help me sustain the thread of life, Somebody.’3

The writers imagine religious victims complaining about God’s silence in the wake of the bombing. The line, ‘Who made this despicable bomb?’ follows pleas to God and Mary as the poet contemplates God’s complicity. The poem foreshadows the narratives described in this chapter of the memory of survivors and the bombing as physical threat and spiritual test.

Hell at the river

Interviewee Miyake Reiko arrived at the Urakami River on 10 August 1945 and observed a scene of ghostly chaos. I introduced Miyake’s testimony earlier, when she narrated her memory of the injured and the dead bodies at the devastated school where she taught. Twenty years of age at the time of the bombing, Miyake was a young teacher at Shiroyama Kokumin Gakkō (National School). Miyake also recalled the scene at the Urakami river after the bombing. The Asahi newspaper printed her recount of the surreal scene of the irradiated and dying who arrived one by one seeking water:

Burned and blackened people were standing in line for water on the stone steps leading down to the river. Young and old alike were groaning, “Water, water.” After a person at the front of the line scooped a handful of water from the river and sipped it, that person never lifted his or her head again. All of them would let themselves fall into the river. The next person in line would take a sip and fall into the river. Another and yet another followed in turn. Miyake gazed at this scene for a while.4

Miyake reports a discomforting memory of suffering. Her telling of her narrative allowed her to confront and, to at least some extent, come to terms with this horrible and painful experience. The retelling of the experience may push her emotional reactions into the background in favour of explaining what happened. For Miyake and for those reading (or listening), the lack of emergency support for those affected magnifies the memory. The narrative evinces the sentiment of the poem, ‘Help me sustain the thread of life. Somebody’. But few people were able to help the injured and suffering in either Nagasaki or Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath. Miyake, too, looked on with a sense of helplessness and confusion.

Miyake’s memory is yet more challenging because water, a life-giving element we take for granted, in this case did not give life but accompanied death. People, one after another, died after drinking, a phenomena which was and remains shocking.5 Even when people arrived at the water, drinking likely caused various complications due to injuries caused by irradiation and burns shock. A recent article about Hiroshima in the Journal of Surgical Education explained that victims drinking fouled water after the atomic bombing led to diarrhea and vomiting, and their irradiation added to the misery.6 Water may have actually aggravated blood loss sustained in injuries. After drinking water, burns victims may enter severe shock which results in death. Burns and trauma may affect all organ systems. Increasing fluid intake above a certain range leads to intracranial pressure, pulmonary edema, or heart failure.7 But the main issue was the contamination of the water supply. The water the people desired was in these circumstances physically dangerous.

There is an attentiveness to suffering in Miyake’s narration. She acknowledges the humanity she observed, undercutting ‘Catholic’ (and other) narratives which over-emphasise the role of graceful death in the face of the atomic bombing.8 Her observance and memory of human tragedy and environmental ruin is supported by local newspaper reports and historic testimonials.9 This report stands in contrast to the hansai narrative of Junshin Girls’ High School in which girls were said to sing ‘Christ, the Lamb’ as they went to their death in the same river.

It is desperation in the cries Miyake relates, not song. The abruptly silenced cry of the people for water in the atomic narrative is specific ‘dangerous’ memory, witnessed by Miyake and shared for those who will listen. Creative minds after the Jewish Shoah similarly imagine ‘silenced cries’ of forgotten suffering. A poem by Jewish German-Swedish poet Nelly Sachs entitled ‘Landschaft aus Schreien’ (Landscape of Screams, 1957) describes a landscape where all that remains is human cries. Sachs incorporates Job’s and Jesus’ screams, depicted as impotent, like ‘an insect in crystal’.10 She connects Job’s scream to Jesus’ cry as he died recorded in the Christian scriptural narrative: ‘My God, why have you forsaken me?’

Likewise, both cries stand at the centre of theology and theodicy for the German theologian Johann Metz.11 For Metz, the suffering of the Jewish diaspora is a ‘landscape of cries’ – linking the Jewish suffering to ‘early Christianity, whose biography… ends with a cry…’12 Sachs and Metz question through their writing who will witness the silent screams, as in the poem quoted earlier.13 Those who cried for water in Nagasaki succumbed to immobilisation and lifelessness. And, after almost seventy years, it is Miyake who carries the cries at the river, burned into her memory. By narration and by sharing her discomforting memory, she is a courageous witness. The telling of the story of the forgotten, silenced ones demands our attention – in her re-voicing and re-imagining.

|

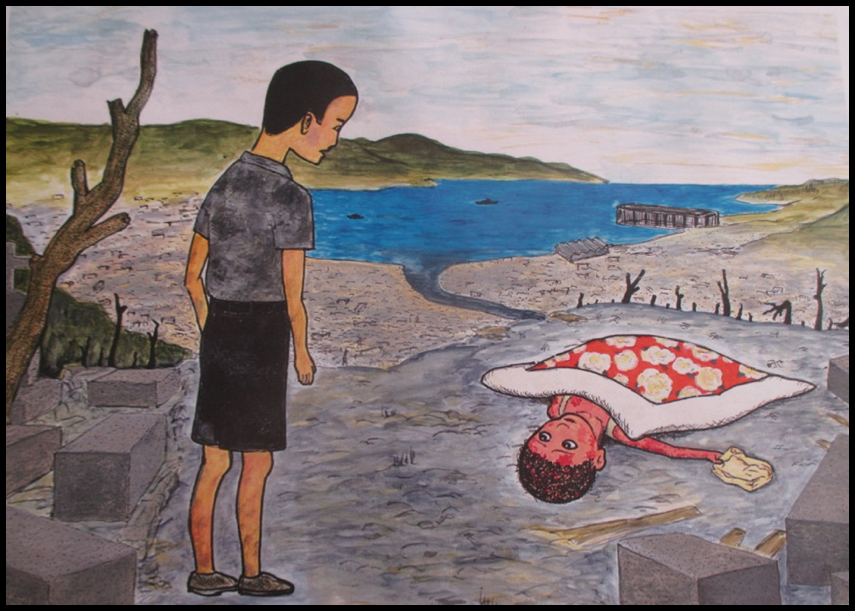

Figure 2. The boy who cried for water, drawn by his son, Nakamura Kōji, used with permission, Nakamura Kazutoshi, 17 January 2019. |

The boy who cried for water

The second mention of a cry for water was by Nakamura Kazutoshi, who discussed his own survival as tribulation or trial. Nakamura told me about an episode he remembered in the aftermath of the bombing.

Soon after the bomb was dropped, 11-year-old Nakamura, searching for his father, found a better view of the destruction from an elevated gravesite south-east of Urakami Cathedral. He came across a boy, lying flat on the ground with terrible burns. In the interview he used a picture drawn by his son to accompany the narrative, showing the scene after he was halted by the boy’s parched cry. I draw on two sources in understanding his story: the picture drawn by his son, Kōji (Figure 2), and the interview record:

My eldest son drew this picture for me (Figure 2) […] this is a child who was burnt by the bomb and thrown to the ground (genbaku de yarareta). He couldn’t handle the heat of the sun […] so I put this futon over him […] here in the cemetery. […] the grave stones had fallen over and there was a bright coloured futon which happened to fall out there. So, I took it and laid it over him […] it [the place] was out of the way, so people were not coming [here] […] this guy had become alone, without even a single person he knew, it was like he was the only person in the world, I felt […]14

Nakamura’s narration intensifies the imagery of forsakenness and abandonment: the boy ‘… was the only person in the world’. He laid a futon blanket over the injured boy in a cemetery, a location which itself epitomises death. The bright colours of the futon in the original colour picture are jarring when set against the rubble of vanquished Urakami and a broken tree. Japanese gravestones in the picture are lopsided, blown awry by the bomb. The boy seeks solace and Nakamura is the ‘Somebody’ in the poem, a witness offering humanity and hope. Nakamura continues:

[…] this was a high place and I could see the sea and I was relieved and thought maybe my father was over there, coming from the station, maybe he was on a road […] I was thinking I would walk when I heard the [boy’s] voice saying, ‘Ni-chan, mizu wo chōdai – water please!’ It was a long way to get water […] and I said, ‘I’ll definitely come back and give you water, so do your best until then!’15

Nakamura subconsciously elides from the discussion his missing family members while the boy’s suffering consumes the kataribe. The cry for help as a reasonable and urgent need challenged Nakamura to action. He said, ‘I’ll definitely come back’. However, he continued his search for his father, who he eventually found. His other family members were also missing, but in his discussion of the boy, Nakamura does not mention them. Nakamura told me later in the interview that together he and his father came across the bodies of his close relatives at home and about the distress of never finding his mother. For now, though, he related:

This time I ran and joined the back of the column of people and finally I got to meet my father. After that, on the way back to the school, I came past here, near Urakami cathedral […] Just as I passed this place, I remembered that I had made the promise to the boy and had to bring him water. So, taking my father’s container, I went back to where the child was.16

Nakamura omits major events within his own narrative by the two words ‘after that’. In the interim his underlying trauma of coming across the remains of bodies of family members unfolded. The trauma may have caused him to forget the boy, until he finally walked past the area once more. When he recalled him, Nakamura took a container of water (his father’s) and desperately ran the final distance:

When I got there and approached, there was a mass of black big flies […] [and] because I was running, WAAA [the flies rose up] [PAUSE] I shuddered with a horrible chill. I had a premonition as I saw that the child had his eyes open, staring into the distance, looking at me and I realised that he had died. Even now, I think I did an awful thing to this boy. [PAUSE] […] all the boy wanted until the last was water […] If only I had gotten him some. Even now when I think of that […]17

The memory of the boy’s cry continues to threaten Nakamura’s sense of identity even as this happened to his eleven-year-old self. His dialogue and transcript shows the signs of ongoing emotional responses to the boy’s death, including the pauses and sound effects (WAAA). I highlighted above, ‘I did an awful thing to this boy’. Nakamura pronounces himself guilty, juxtaposing the needs of the boy against his own failure to respond. The boy’s cry for water is Nakamura’s ‘dangerous’ memory, which he cannot dismiss from his mind.

Survivor Guilt

Testimony of trauma is untidy. Neither Miyake nor Nakamura describe an ordered narrative with a beginning and an end.18 Nakamura put a futon on the boy, talked to him and brought water, but his primary memory is his failure to return before the boy’s death. His narration implies he is entrapped by a psychological ‘survivor guilt’. Summarised simplistically, survivor guilt is a remorse felt by those left alive after extreme events when others, including friends, family and acquaintances have died. Nakamura’s perception of his own guilt in the horror of the aftermath, ‘I should have done more’ or ‘tried harder’, is ineluctable.

A complication for Nakamura is the likely traumatic link to his (here) unmentioned shock of finding other bodies, including close relatives and the agony of never finding his mother. The shock of finding the boy’s body seems to evoke the unresolved lost body of his family member. He recognizes that the search for his father (and mother) was legitimate but suggests that, by neglecting to return quickly, he failed to show sufficient affection or care (aijō) to the boy:

[…] that I couldn’t get water for this child demonstrates I did not have enough compassion […] But maybe that was not the case […] Apart from finding my father, I was worrying most about finding water for this boy. I could see the river, but this was the top of a mountain, so there was no water […] The thing I was most afraid of was that, in the time it took to get water to this boy, my father would have gone away.19

Nakamura’s narrative exposes his inadequacy and his ongoing struggle with life after the atomic bombing. After his father, his next worry was finding water. Coming upon the boy dead, his actions were made redundant and this in turn may link to the lack of agency he says he experienced in his subsequent life.

The guilt described here by Nakamura bears some similarity to Ozaki Tōmei’s memory of his experiences I will describe in the following chapter. Both, as young men, later struggled with suicidal thoughts. But for Nakamura, like Miyake, sharing his story is the imperative that remains.

Nakamura’s sense of futility is juxtaposed against Miyake’s sense of agency after the bombing, exemplified by the continuation of her work as a teacher in Shiroyama, alongside Urakami. Compared to those who lived in Urakami, Miyake was privileged because her home was preserved and her family life continued, while Nakamura and other survivors were refugees, forced to seek places to live away from Nagasaki. She lost friends to the atomic bombing, though, especially her colleagues and students as she had worked at the Shiroyama National School, close to Ground Zero. Nakamura articulates his feelings of impotence in dealing with his experiences. He dwells on this ‘dangerous’ memory, ambivalent about his perceived failure. His laying of a futon over the boy and bringing water were actions rendered meaningless in his own mind in view of the boy’s death. Nevertheless, his actions are an understandable human response. Later, as a refugee, he was unable to take control of his own life, missed out on educational opportunity and contemplated suicide. Further, he had no outlet for at least sixty years to discuss his memory of the boy. For Nakamura, speaking about this ‘dangerous’ memory reminds him of feelings of ambivalence and impotence. However, his sharing of the distressing experience and his son’s drawing of the scene appears to have been cathartic.

|

Figure 3: Kataoka Sada, photograph from 信仰の礎 : 浦上公教徒流配六十年記念, a book produced in 1930, representing sixty years after the Fourth Persecution, Urakami Cathedral. Public domain. |

Withheld water as persecution

After a lifetime of hearing communal ancestral narratives, an Urakami Catholic listening to Nakamura’s or Miyake’s memory of the ‘cry for water’ might well be drawn to a comparable story found in the public history of the persecutions of the Tokugawa era. The father of interviewee Kataoka Chizuko, the historian Yakichi, wrote about the persecutions of the late nineteenth century and a semi-autobiographical account of his grandmother’s experiences.20 His grandmother was a mother with four young children who narrates her story even as she was singled out as one of the weakest of those exiled by the Nagasaki magistrate. Officials separated Sada from her family into the group made up of elderly, mothers and babies.

This analogous cry in the Fourth Persecution is found in a diary, or experience-record (taiken-ki) recorded from the perspective of Sada, Chizuko’s great-grandmother (Figure 3).21 The diary may have been orally committed to paper, an early record of oral history. With her four daughters (aged twelve, nine, five and two years), Sada was exiled together with other Catholics, to Wakayama, a province found south of Osaka on Honshu island in the Kansai region of Japan, departing 6 December 1870 from Honbara-gyō, Ippongi in Urakami. Officials separated the women and men and the youngest children went with their mothers. The women wore an outward sign of their illicit faith, their Catholic baptismal veils (anima), as they set out.

The group spent seven days and nights on a boat on the way to Wakayama. Here, officials transferred them to a temple where they saw the men. The journey was arduous and relatives and friends were also often separated from each other. After twenty days, the groups were once again split up on gender lines and Sada, separated on this occasion from her three older children, went with the women with small babies and the older people who were ‘unable to work’ to a horse stable. Here, the group was forced in to the small space. The jailers stripped the Christians of their rosaries and Mary flags.22 Taking away their holy objects was an attempt to strip the kirishitan of any concrete items which helped them retain and practise faith.

Evidence of traumatic experiences is recorded in Sada’s diary. She remembered sordid conditions in the stable that lasted for over six months from June 1871 until January 1872. There was much sickness and, with no medicine and precious little water, nine people died from infectious diseases. When someone died, the women prayed (orashio, the prayers of the hidden Christians) and put an anima or veil on the body, which remained there overnight. The veils placed over the corpses turned black immediately, due to the presence of lice attacking the bodies. Those who remained in the confined space, remembered Sada, were nauseated by the bodies and their smell.23

The next section of the diary described cries for water similar to those of the atomic narratives.24 Water emerges in Sada’s narrative as a similarly ‘dangerous’ element. Giving in to those withholding the water meant abandoning faith causing death to your soul; otherwise the Christians faced physical death due to deprivation. Sada reported that when the overseer from Urakami came in and saw the dead bodies, he yelled, ‘You should give up (renounce your faith)!’ Even the apostates who had formerly been kirishitan betrayed their compatriots and refused to provide relief.

At the time, even as we cried, ‘Water please!’, we were told, ‘There is none’ and were not given any. There were people outside working, who had apostatised and so we asked, ‘Please give us water and we won’t tell anyone’, but they gave us nothing. The sick cried ‘Water, water!’ repeatedly, close to death. The children pleaded with their parents, ‘I want water!’ and ‘I’m hungry!’ and many of the parents gave up […] [Later,] on 7 April, in the 6th year of Meiji [1873], we returned home to Urakami.25

Fear of deprivation and death is reflected in the ‘cries for water’.

The cry for water in this older narrative, as in Miyake and Nakamura’s story, protests unjust treatment. The role of witnessing the experience truthfully as kataribe, is essential (although Sada is neither a kataribe nor an hibakusha). By recording and retelling memories of all three experiences, Sada, Miyake and Nakamura protest unthinking subjection to dehumanisation and victimhood. A second similarity among the narratives is the significant challenge to the people’s religious faith. An implicit challenge in the narratives of 1945 is potential subversion of the faith of the victims. Those who apostatised in the persecutions imagine both God’s betrayal and their own betrayal of God. However, the choice for those exiled was stark in Sada’s account. They had to choose between death/dehydration or abandonment of faith; physical deterioration or spiritual bereavement. Sada reports of mothers apostatising for the sake of their children.

Among 289 exiles to Wakayama, community historian Urakawa Wasaburō details 96 who died and 152 who renounced their beliefs. If correct, only 41 exiled believers avoided both death and apostasy in the group sent to Wakayama.26 Those who did not give up faith prayed or beseeched God and Mary, cried ‘water!’ and some died. Some who apostatised were enrolled in work for the magistrate and some returned early to Urakami village.

The atomic bombing was, like the Fourth Persecution, a threat to Catholic faith and dangerous to their identity, world view and discernment – truly a Fifth Persecution. Water was ‘dangerous’ to those who called for it. In atomic memory, water was physically dangerous to consume, whereas for Sada, the withholding of water and the cries for water represented a hellish reality, facing up to de-Christianisation, repression and abuse.

The parallel cry for water in the atomic narrative alongside the Catholics’ past persecution raises another issue. There is a question around the possibility of hope versus despair. Miyake and Nakamura protest the ‘impossibility’ of the atomic narrative by telling their own versions of the cry for water. Sada’s is also an ‘impossible’ situation, which she lived through with her two-year-old child. The cry for water in atomic literature is often interpreted as a stark anti-nuclear message or a call for peace against war. However, the cry for water is doubly a ‘dangerous’ memory in the Catholic narrative and as reframed by their consciousness of suffering, reflects both physical and spiritual concerns, remembered previously within the Fourth persecution.

For the survivors, Miyake, Nakamura and Sada, the legacies of trauma continue to manifest long after the originating event.27 Trauma studies theologian, Flora Keshgegian, writes that the key to transforming memories of victimisation is to highlight instances of resistance and agency for the people involved. In the narration of such memories, the humanity of the dehumanised victims is re-imagined. Victims’ cries and actions seeking water before death reanimate memories of agency and their fight for life. Kataoka Sada was sent with her baby along with the infirm and old, and displayed faithfulness and resilience within the modern Catholic narrative. In the rendering of the story by her grandson Yakichi, she is one of forty-one believers who returned to Urakami and were granted life. She returned on April 7 1873, part of the faithful and enduring remnant. The roof of her house was demolished and the walls were falling in, but she endured.28 Her survival signals resistance and her return, God’s faithfulness. Later, grandson Yakichi and great-granddaughter Chizuko survived the atomic bombing while many others lost their lives.

Of Pollution and Restoration

Many of those who cried for water in 1945 ended their lives enveloped in water which became their grave. The atomic bombing brought severe environmental consequences, including blast, fire, and irradiation. The consequences of the bleeding of radioactivity into oceanic ecosystems since the 2011 Fukushima disaster presents devastation on an even greater environmental scale, threatening water’s purifying qualities. The Urakami river gradually returned to its wholesome state. In a blog post entitled: ‘For Nagasaki citizens, the river is for the repose of souls’, local teacher and illustrator Ejima Tatsuya estimated that between 10,000 and 20,000 bodies were in the Urakami river for at least a year after the bombing.29 Ejima writes that for the hibakusha of the day, the water represented ‘life-giving’ properties. The water, physically ‘dangerous’ for those victimized at the time, in death enabled purification and restoration. In Shinto belief, water is a purifying agent.30 The water was a symbolically appropriate and poignant resting place for the dead, a moving, living ecosystem. The remains lingered in the river for a long period, a ‘dangerous’ pollution as the bones were washed and washed again. The abandoned dead coalesced into the waterways, absorbed in the ecosystem, although for Catholics this was not a consolation.

Despite the healing powers of water, the ‘silenced’ cry for water re-voiced in the interviews and recorded in this collective biography remains jarring and shrill. A lack of resolution is expressed by Nakamura, Miyake and Sada, who recall the ‘danger’ and the ‘hellish’ scenes they observed.31 Physical and spiritual dangers are amalgamated in these narratives.

‘Give me water!’, a harsh cry of the atomic narrative, is ‘dangerous’ memory in the kataribe voice, protesting the peoples’ harsh treatment. The work of those breaking through silence after the bombing and remembering the cries as the witnesses or kataribe allow a release of emotion as described by Nakamura, Miyake and Sada.32 The ‘silenced’ cry reanimates generationally transmitted experiences of suffering and an ongoing challenge against oppressive and unfair treatment. The kataribe tradition channels the Urakami Catholics’ knowledge and memory through emotion and subjective experience. The cry for water shows how Urakami and the Catholic remnant were doubly and triply marked by societal oppression, physical pollution and environmental destruction. Yet the bodies of many were graciously enveloped by the element of water, itself a symbol of purification and hope.

Three especially potent symbols emerged in the interviews in the process of considering the atomic bombing: Mary, the Cathedral, and the ‘cry for water’. Past communal narratives assist in dealing with experiences of atomic desolation and loss. In the later part of the book introduced in this excerpt, I discuss the future of memory and how ‘dangerous’ memory provides reason for future choices. Even as their time on earth draws short, the kataribe continue to imagine their ongoing role as prophets or visionaries. Therefore, I continue by raising the themes of politics, hopefulness, lament and protest for examination alongside the rich and compelling survivor narratives.

Sources

Andrews, Molly. “Beyond Narrative: The Shape of Traumatic Testimony.” In We Shall Bear Witness : Life Narratives and Human Rights, 147–66. Madison, WI.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014.

Bergen, Leo van. Before My Helpless Sight: Suffering, Dying and Military Medicine on the Western Front, 1914–1918. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Ejima, Tatsuya. “Nagasaki shimin ni totte, kawa wa chingon no basho: Urakami gawa ittai.” Blog. Atorie Cho Shigoto nikki. http://hayabusa-3.dreamlog.jp/archives/51349615.html.

Fenn, Richard. “Ezra’s Lament: The Anatomy of Grief.” In Lament: Reclaiming Practices in Pulpit, Pew, and Public Square, edited by Sally Ann Brown and Patrick D. Miller. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2005.

Genbaku taiken o tutaeru kai. Give Me Water: Testimonies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Translated by Rinjiro Sodei. Tokyo: Citizens Group to Convey Testimonies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1972.

Kataoka, Yakichi. Urakami yonban kuzure Meiji seifu no kirishitan dan’atsu. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1963.

Keshgegian, Flora A. Redeeming Memories: A Theology of Healing and Transformation. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2000.

Mano, Keita. “Nagasaki: Urakami Kirishitan ‘yonban kuzure’ 150 nen de kikakuten.” Asahi Newspaper online. September 4, 2017, Digital edition, sec. Culture. http://www.asahi.com/articles/ASK475W4QK47TOLB00P.html.

Metz, Johann Baptist, and J. Matthew Ashley. “Suffering Unto God.” Critical Inquiry 20, no. 4 (1994): 611–22.

Minear, Richard H. Hiroshima: Three Witnesses. Chichester: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum. “Sculpted Basin.” Museum website. Nagasaki Atom Bomb Museum, 2017. http://www.peace-nagasaki.go.jp/english/information/i_02.html.

Nagashuu Shinbun. “Amari shirarenu 2 man tai no ikotsu hibaku 1 nengo ni shuushuu shi maisou.” Newspaper. Higashi Honganji Nagasaki, May 18, 2009. http://www.h5.dion.ne.jp/~chosyu/amarisirarenu2manntainoikotu%20hibaku1nenngonisyuusyuusimaisou.html.

Nakamura, Kazutoshi. Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum. Interview by Gwyn McClelland, February 23, 2016.

Namihira, Emiko. “Pollution in the Folk Belief System.” Current Anthropology 28, no. 4 (1987): 65–74.

Okada, Gen. “Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Asahi Shinbun. December 2008, sec. Nagasaki Nooto. http://www.asahi.com/hibakusha/english/shimen/nagasakinote/note01-16e.html.

Selden, Kyoko Iriye, and Mark Selden. The Atomic bomb: voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1989.

Shijō, Chie. Urakami no genbaku no katari: Nagai Takashi kara Rōma Kyōkō e. Tōkyō: Miraisha, 2015.

Southard, Susan. Nagasaki: Life after Nuclear War. New York: Viking, 2015.

Thompson, Janice Allison. “Theodicy in a Political Key : God and Suffering in the Post-Shoah Theology of Johann Baptist Metz.” PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 2004.

Urakawa, Wasaburō. “tabi”no hanashi : Urakami yonban kuzure. Nagasaki: Katorikku Urakami Kyoukai, 2005.

Wiebelhaus, Pam, and Sean L. Hansen. “Managing Burn Emergencies.” Nursing Management 32, no. 7 (July 2001): 29–35.

Yoshida, Kayoko. “From Atomic Fragments to Memories of the Trinity Bomb: A Bridge of Oral History over the Pacific.” The Oral History Review 30, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 59–75.

Notes

In the days after the bombing, there were some who believed it was not helpful to give water to survivors and others who thought the least they could do was to fulfill someone’s dying wish. See, for example, Genbaku taiken o tsutaeru kai, Give Me Water: Testimonies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, trans. Rinjiro Sodei (Tokyo: Citizens Group to Convey Testimonies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1972). Kyoko Iriye Selden and Mark Selden, The Atomic bomb: voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1989), 95. Richard H. Minear, Hiroshima: Three Witnesses (Chichester: Princeton University Press, 1990), 192.

Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, “Sculpted Basin,” Museum website, Nagasaki Atom Bomb Museum, 2017, accessed 27 September 2017.

Poem read by the Literati group for Appealing the Dangers of a Nuclear War, March 3, 1982 and quoted in Kayoko Yoshida, “From Atomic Fragments to Memories of the Trinity Bomb: A Bridge of Oral History over the Pacific,” The Oral History Review 30, no. 2 (July 1, 2003): 74.

Gen Okada, “Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Asahi Shinbun, December 2008, sec. Nagasaki Nōto, accessed 24 May 2016.

Water is required for casualties, but fluid is not absorbed well by mouth. Shock should be treated in accordance with medical advice. Water assists those who have gone into shock, but in this case the water may have been polluted and the amount they drank is unclear. Leo van Bergen, Before My Helpless Sight: Suffering, Dying and Military Medicine on the Western Front, 1914–1918 (New York: Routledge, 2016), 233.

Don K. Nakayama, “Surgeons at Ground Zero of the Atomic Age,” Journal of Surgical Education 71, no. 3 (May 1, 2014): 446.

Pam Wiebelhaus and Sean L. Hansen, “Managing Burn Emergencies,” Nursing Management 32, no. 7 (July 2001): 34.

Shijō effectively describes the Catholic narratives in her book: Chie Shijō, Urakami no genbaku no katari: Nagai Takashi kara Rōma kyōkō e (Tōkyō: Miraisha, 2015), 108.

Miyake’s narrative is supported by: Tatsuya Ejima, “Nagasaki shimin ni totte, kawa wa chingon no basho: Urakami gawa ittai,” Blog, Atorie Cho Shigoto nikki, accessed 21 June 2016, http://hayabusa-3.dreamlog.jp/archives/51349615.html. Genbaku taiken o tutaeru kai, Give Me Water; Selden and Selden, The Atomic bomb. Nagashuu Shinbun, “Amari shirarenu ni man tai no ikotsu hibaku ichi nengo ni shuushuu shi maisou,” Newspaper, Higashi Honganji Nagasaki, May 18, 2009, accessed 24 June 2016.

Sachs refers to the Jewish Shoah or Holocaust as well as Hiroshima and other historic events. Janice Allison Thompson, “Theodicy in a Political Key: God and Suffering in the Post-Shoah Theology of Johann Baptist Metz” (PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 2004), 226.

Metz is writing of the Christological cry from the cross, reflecting a ‘landscape of cries’ and of Israel as a people who respond to history through memory in Jewish tradition. Theodicy, he continues, is ‘the’ question of Christian theology. Johann Baptist Metz and J. Matthew Ashley, “Suffering Unto God,” Critical Inquiry 20, no. 4 (1994): 614.

Kazutoshi Nakamura, interview by Gwyn McClelland, Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, February 23, 2016.

Molly Andrews, “Beyond Narrative: The Shape of Traumatic Testimony,” in We Shall Bear Witness : Life Narratives and Human Rights (Madison, WI.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), 43.

Kataoka Yakichi calls the record a ‘diary’ but it is not clear when Sada wrote it. She probably completed it in the years after 1873 when the survivors returned to Urakami. Yakichi Kataoka, Urakami yonban kuzure Meiji seifu no kirishitan dan’atsu. (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1963). Today, the diary is held by the Junshin University library, Megumi no Oka, Nagasaki. Keita Mano, “Nagasaki: Urakami Kirishitan ‘yonban kuzure’ 150 nen de kikakuten,” Asahi Newspaper online, September 4, 2017, Digital edition, sec. Culture, accessed 26 August 2017.

Kataoka Yakichi, Sada’s grandson, recorded Sada’s experiences by including her diary in his book about the Fourth Persecution. Yakichi Kataoka, Urakami yonban kuzure Meiji seifu no kirishitan dan’atsu. (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1963), 162–67.

This is the process referred to previously (Chapter 5), by which ‘holy’ objects were confiscated by the Nagasaki magistrate. Later, many of these items were transferred as exotic objects to Tokyo, where they remain in the Tokyo National Museum. The various items taken away are carefully listed in Kataoka, Urakami yonban kuzure, 170. In 2019, the Catholic community asked that these objects of significance be returned to Urakami.

Urakawa in his book, Tabi, relates that the lack of water during the persecutions especially affected the women and reports that men managed to use bamboo to redirect the water from the roof gutters. Wasaburō Urakawa, “Tabi”no hanashi (Nagasaki: Katorikku Urakami Kyoukai, 2005, 1938), 149.

Flora A. Keshgegian, Redeeming Memories: A Theology of Healing and Transformation (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2000), 120–21.

Ejima, “Nagasaki shimin ni totte, kawa wa chingon no basho: Urakami gawa ittai.” The Higashi Honganji temple’s Buddhist ladies’ association began cleaning up bodies from March 1946, according to an article which corroborates a figure of approximately 20,000 bodies across Urakami, although the number in the river is unclear. Nagashū Shinbun, ‘amari shirarenu’. Southard writes that barrels were placed at intersections in Urakami Valley for the collection of ashes and bones and there are reports of human bones collected from the river and buried under trees. Susan Southard, Nagasaki: Life after Nuclear War (New York: Viking, 2015), 128.

Emiko Namihira describes rituals for the dead as involving washing the bodies with water, as well as those who have encountered the dead. She notes that if ‘the pollution of death remains strong even after a fixed time has passed… this is thought to be all the more dangerous’. Emiko Namihira, “Pollution in the Folk Belief System,” Current Anthropology 28, no. 4 (1987): 66.

The ‘danger’ is exerted against the tendency for collective understanding of remembering of the atomic bombing without acknowledging the common humanity observed by these witnesses. They remind us to remember the ‘other’ and of hope for the oppressed and vanquished.

A sacred moment is identified in the breaking through of grief and lament, which I discuss in further detail in Chapter 9 of my monograph. Theologian Richard Fenn makes the claim that a sacred moment breaks through in lament (not about Nagasaki, but about victims in general) in Richard Fenn, “Ezra’s Lament: The Anatomy of Grief,” in Lament: Reclaiming Practices in Pulpit, Pew, and Public Square, ed. Sally Ann Brown and Patrick D. Miller (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2005), 139.