Introduction: The Lies of War

Steve Rabson

Months before the U.S. invasion of Okinawa in April. 1945, thousands of civilians evacuated Okinawa with their families to rural areas of mainland Japan. Tamaki Rieko’s father, a physician, decided to stay as his duty in the war effort. Among his family of ten only Rieko survived the battle. She writes, “even as the onslaught worsened, Okinawans believed that, if they could just endure a little longer, a huge force of support troops from mainland Japan would be coming to their rescue.” Later the family decides to leave the cave-shelter where they’d evacuated and move farther south to avoid advancing U.S. forces. “We heard from the adults speaking in low whispers about what the enemy did to prisoners of war. The ‘devil-beast Americans’ would slice them up into little pieces, they said. We firmly believed this, which was . . . why we had to leave the shelter.” Of the battle’s end she writes, “How could the war be over, I wondered again, never imagining that it could end with Japan’s defeat. After all, we’d been taught that Japan was ‘the land of the gods,’ and no matter how desperate the situation might be, the kamikaze winds would blow and bring the nation victory.”

In the early 1960’s Defense Secretary Robert McNamara kept issuing optimistic predictions of rapid success for Green Beret “advisors” in Vietnam. Even after the Johnson administration began sending draftees there in mid-1965, McNamara promised they would be home by Christmas. In 1969 Richard Nixon touted his “Vietnamization” war policy as saving American lives. More than 20,000 Americans died during his presidency.

These are the lies of war. To them must now be added George W. Bush’s claim that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, a lie that resulted in 4,424 American deaths and 31,952 wounded. The war’s total death toll is estimated at 1.2 million, while millions more became refugees.

Hillary Clinton voted for the Iraq war as a senator. As Secretary of State she reportedly pushed for increasing U.S. forces in Afghanistan by 60,000, far more than what President Obama eventually ordered. This, after former Afghan President Hamid Karzai told the Washington Post, “I don’t think military means will bring us [peace]. . . . We did that for the last 14 years and it didn’t bring us that.” Then she boasted in her 2014 book Hard Choices that she was the one to “seal the deal” for military intervention in Libya. That country subsequently descended into the chaos of a failed state that not only took the life of a U.S. ambassador and tens of thousands of Libyans, but forced hundreds of thousands into exile, a mass exodus that continues to this day. Yet the Democratic Party nominated her for president.

In her postscript below on the deployment of Japan Self-Defense Forces to the Iraq War, Tamaki Rieko writes of “Human stupidity endlessly repeating,” which recalls this verse from Pete Seeger’s song “Where have All the Flowers Gone” (1955):

Where have all the soldiers gone?

Long time passing

Where have all the soldiers gone?

Long time ago

Where have all the soldiers gone?

Gone to graveyards every one

When will they ever learn?

When will they ever learn?

Amidst War’s Devastation

“Oh, God. Please don’t let the shellfire tear up my arms and legs! I know I can’t escape it flying all around me, but couldn’t stand the pain. Just let me die quickly!” This was my prayer at age ten.

Nearby lay corpses, and people with their arms and legs shredded by shrapnel, people with their intestines sticking out, dead mothers with crying babies on their backs, and people trying weakly to brush off maggots that crawled out of their wounds. I knew I could be one of them tomorrow, or even in the next minute. Trembling with fear, I envied those who had died instantly.

Of my family of ten swallowed up by the fierce fighting in southern Okinawa, only I survived.

War is a giant monster randomly devouring precious lives—young children, the elderly, gentle mothers–and cruelly robbing families of their homes.

My father, Sakai Ginnosuke, was a doctor. With more signs every day of approaching war and more evacuees leaving Okinawa, he must have thought about joining them.

|

Rieko’s father, Sakai Ginnosuke, her older brother Shōkō, and Rieko |

But the national government was urging doctors not to leave the prefecture. My father, a man of integrity, thought evacuating would violate his professional ethics, and decided to stay. I had wanted to join the students evacuating from my school even if it meant separating from my family, but my grandmother refused permission. She probably thought that, as a fourth grader small for my age, I was too young. One group of students at our school was assigned to the ship Tsushima-maru. On August 22nd as it neared its destination at Kagoshima in Kyushu, an enemy torpedo struck, sinking the ship. 1,788 on board were swallowed up by the ocean with only 59 students rescued. Later we learned that sharks swarmed in those dark waters, killing many. I can still remember the names of my classmates who died in an age when even children were sacrificed in a war that brought death and destruction to every segment of society.

The massive air raid on Naha City

My mother died when I was a baby, so her mother, my grandmother Sumi, cared for me and my brother. She opposed evacuation of the children and elderly in our family, probably thinking she wanted to be with us if we died. Thus it was our fate to be caught in the October 10, 1944 air raid on Naha City, and trapped later in the devastating ground battle.

In those days every family built a bomb shelter in their garden or in a nearby open space, digging a hole large enough for all of them. Ours was in one corner of our garden with large camphor trees. The hole was dug deep, and old tatami mats laid over it were covered with soil where grass grew, so seen from the air was what looked like just another garden. Skillfully camouflaged, it was where we could seek safety at a moment’s notice.

On the morning of October 10, 1944, I was hurrying to finish breakfast before leaving for school. The air raid siren hadn’t gone off, but we heard a strange rumbling in the distance. Still holding my chopsticks, I ran barefoot out to the garden with my older brother and the maid. My brother, a second-grader in the prefectural middle school, was only fourteen, but his voice sounded unusually grown-up when he told me, “Yakka (my childhood name), you’re not going to school today!” and ran out to warn the neighbors. As soon as he got back, he yelled for us to “Get to the shelter, now!” and, carrying Grandmother, led us out to the garden and into the bomb shelter. My father and the maid followed, climbing slowly down inside. We could see, far off in the sky overheard, the glitter of silver warplanes steadily approaching–the B-29’s. From the ground far below them, our army’s anti-aircraft cannons fired what looked like white strands of silk into the air. “Those damn guns’ll never reach ‘em,” Father grumbled. He seemed to spit out these words, then fell silent. For me, a fourth-grader in National School,” as all Japanese public grade schools were called to instill patriotism during the war, that day was long and boring. The adults were super-serious about being in the shelter, but I just wanted to run right out of there. I asked for some of our “emergency rations,” dried cuttlefish and brown sugar, to relieve the boredom. For me, still a kid, this seemed only natural after I had done everything I learned from our regular air raid drills—putting on my monpe (fatigue work pants), donning my bomb-protection hood, and hitching up my first-aid and emergency bags on my shoulders. Surely, now that a raid was actually happening, we could eat the emergency rations. “Absolutely not!” said Grandma with a stern face. This seemed unreasonable to me. Hadn’t we gone through all those drills day after day just to prepare for the real thing?

So I had to spend long boring hours cooped up in the shelter. That evening when we began hearing explosions some distance away, Father’s younger brother Yoshihiko showed up. He was the office manager at my father’s hospital. He’d come with the nurses to tell us how they’d struggled to evacuate the patients from the hospital building that had burned to the ground as had most of Naha City.

When we left the shelter a little later, I saw that the night sky had turned bright red. A restless breeze was blowing and there was a strange smell in the air. Now, in my childish mind, I finally realized how serious this was. During the hours we’d been in the shelter, Father’s hospital had burned down and the houses in Naha were being devoured in red flames and black smoke. Yet, though I could feel that this was an emergency, for some reason I didn’t panic.

With enemy planes still crisscrossing in the sky overhead, our maid decided to leave for her family’s home in Shuri. Father and grandmother told the five nurses who lived at Father’s hospital, now in ruins, that it was too dangerous for them to stay in Naha. They agreed to leave the city, and return when it was safe with their parents’ permission. Promising to meet again then, everyone was in tears when they left.

We could hear more explosions as firebombs continued to fall. Everywhere the city had turned into a sea of fire. I wore my bomb-protection cap, soaked in water so it wouldn’t burn, and wrapped myself in a blanket as we left Naha for the town of Tomari with the adults guiding us around houses in flames. On our way through the side streets at Wakasa-machi, we saw that the concrete covers had been removed from most of the large turtleback family tombs now turned into air raid shelters for the people seeking safety inside.

Brushing off the smoke and sparks, we finally arrived at the foot of Tomari Bridge. Father’s parents, who lived in Tomari, were waiting there, so somehow they must have known where to meet us. Now they joined us as we wended our way north. Leaving the burning city of Naha behind, we climbed the hill toward the town of Shuri now totally dark. For a child like me, it must have been a hard journey, but I have no memory of it until we reached a house in a dense grove of trees. That night our exhausted family slept in one of the rooms there.

Ginowan Village and Kakazu

The next morning we rode in a horse-drawn carriage to Ginowan.

That night we stayed at the home of Arakaki Bunkichi, Father’s cousin and the principal of Kakazu National School in Ginowan. The next day Kakazu’s mayor located a place for us. It was a small rented house where we had to stay all cramped together–our family, Grandpa and Grandma’s families, Uncle’s’ family, and the maid, Masako–a total of eleven people. Over and over again we heard the slogan “Covet nothing until victory,” and how as loyal Japanese we must “endure” anything. I felt totally confined in that house, but couldn’t go to school either. Almost all the schools in Okinawa had been taken over by the Japanese army for barracks, and the students had to hold classes in thatched roof huts where the lessons were mainly air raid drills. To protect ourselves when bombs fell, we were told to lie down on the ground, press our eyes closed with our fingers, and stick our thumbs firmly in our ears. This was so the bomb blast wouldn’t blow out our eyeballs and burst our eardrums.

Stationed at the school in Kakazu was the Ishi Cavalry Battalion, and we had to gather hay for their horses. This was called a “consignment.” Anything metal that could be converted to military use also became a “consignment.” The bronze statue of 19th century educational reformer Ninomiya Sontoku in the schoolyard, our families’ pots and pans, and even rings were all turned over to “our sacred nation.”

Since I’d never used a scythe before, I had trouble cutting grass for the cavalry horses, and watched enviously as the local children skillfully sliced away. When they saw how I was struggling, they all kindly gathered to help me cut. Every adult and child worked for the army. The spunky kids showed the soldiers where to find strawberries and mulberries, and that the grain tips of susuki grass were edible, as were raw potatoes after wiping them off on sleeves or cuffs.

All of us were much too cramped in the small house we had rented, so Uncle’s family rented another house with the unusual name “Sandaajiima.”

Three days after the massive air raid, my grandfather, elder brother and uncle went to see what had happened to Naha. When they returned, they told us that both their home in Wakase and the house in Tomari had survived the fires. But thieves had carried off all the roof tiles, wall sidings, and floor boards of the house, and also of Mr. Kinoshita’s soy sauce store next door. The adults called this “kama jishi kūtōtan,” an idiom in Okinawa dialect meaning “to taste bitterness.” But when I mistakenly heard the word “shishi,” meaning meat, I complained to Grandma that I wanted some, too.

Anyway, our family was happy to learn that, although thieves had stripped our house, they had left our belongings inside. This is what’s called “fortune in the midst of misfortune.” There was a clear reason why our stuff had been spared. After the air raid, the police used our house as their headquarters. “It has firewood, a bath, a well, and large rooms that made it perfect for us,” the policemen had told Grandpa, adding proudly, “in return for using it, we kept your belongs safe.” In the days that followed we loaded our belongings on to a horse-cart for transport to the house in Ginowan where we had evacuated.

As we began our lives there, I pressed the others to tell me what had happened in Naha—to my school, Tenpi National Elementary School, and my friends. I pestered them to take me to the city, but everyone refused, which put me on the verge of tears. Yet, I have to say, it was kind of fun in this new place, though, with almost daily air raid alerts, we had to keep moving back and forth from the shelter.

With his hospital burned down, father had only his books and writing brushes to occupy himself, and seemed to have lost interest in his favorite hobbies playing shakuhachi bamboo flute and reciting lines from classical Noh drama. Always a man of few words, he grew increasing silent.

My older brother Akimitsutraveled from Ginowan to the Second Prefectural Middle School in Naha. Though it was still called a school, no one studied there. The “lessons” consisted of manual labor for the army and military drills. Then, when he got home, he practiced kendō bamboo sword fighting with the landlord’s eldest and his second son who was about the same age as Akimitsu. The two became close friends having both attended the First Prefectural Middle School.

In those days Okinawa had eight or nine middle schools. Competition was fierce, and even now when I hear about someone who graduated from a pre-war middle school, I am much impressed. Yet even those gifted students had to change from their black school uniforms into “home defense force” fatigues, pull on gaiters over their shoes, and carry shovels on their shoulders to school.

Every day, with help from the maid Masako, Grandma Sumi devoted all her efforts and skills into making delicious meals from the meagre supply of available foodstuffs.

Having lived on a farm, Father’s parents went out walking in the rice fields to catch small frogs so we could enjoy them barbecued. I was amazed that even small frogs could have such a wonderful aroma and flavor. I can still remember that crispy taste. Back then the whole family worked together to pull through those very hard times.

In Kakazu lots of the limestone caves called “gama” were being used as bomb shelters.

Grandfather again applied his skills learned on the farm to build us a shelter that seemed more like a new house. Our gama was fully furnished with a tatami floor and chest of drawers. He channeled water from a spring in the cave to places convenient for cooking and washing clothes. To me it seemed no shelter could possibly be better than this one, and that we would certainly be safe here no matter how many bombs fell. Yet we never had a chance to use it.

Father is drafted

Two months later, just after New Year’s 1945, Father’s “red letter” draft notice arrived. He’d been assigned as medical officer to the Tama Brigade. The day he left I waited until late that night, forcing myself to stay awake, but he did not come home. Around the same time his younger brother, my uncle, was drafted into an infantry unit. Despite Imperial Headquarters’ upbeat announcements that “our forces are winning,” the air raids got worse every day, and the army seemed to be in a state of confusion. One evening a month or two after he was drafted, Father came home unexpectedly for a brief “family leave.” Frightened by the gravely anxious expressions on the adults’ faces as they gathered around him, I was unable to approach or speak to him. For the first time, I saw the Father I knew only in his white hospital uniform and men’s kimono sitting on our rain-dampened porch in an army officer’s uniform with its long sword and knee-length military boots.

Born in 1906 into a farming family in the countryside, Father had been an exceptionally bright child. With his parents’ permission, he attended Shuri Elementary School and later the Second Prefectural Middle school. With his outstanding grades there and the strong recommendation of the principal, Shikiya Kōshin (later Government of the Ryukyu’s chief executive and the first president of Ryukyu University during the U.S. military occupation), Father entered Jikeikai Medical University in Tokyo. Though struggling to make ends meet as a student, he graduated to become a physician. So that was his profession, but with his talents in calligraphy, Noh drama recitation and shakuhachi bamboo flute, I always considered him more a person of the arts. Then, swallowed up by the war, he had not yet turned forty when the army drafted him as a medical officer. Knowing this might be the last time we would see him, Father’s “family leave” seemed all-too-short. When the time came for him to return to duty, he picked me up and hugged me, but still I could say nothing. It was the first time I can remember him hugging me, and can still feel today his firm embrace and that starchy army uniform against my skin. A second or first lieutenant at the time, he left his sorrow-stricken family and returned to his unit with two lower-ranking soldiers. Even as a child, I had a fearful premonition that we would never see him again. My uncle, too, after entering the army, never returned home.

Private Inazuma, a former medical student stationed as a medic in the Ishi Battalion at nearby Ginowan, visited us often at our rental house in Kakazu. Father and Uncle had taken a liking to him, and he soon became friends with everyone in our family. When my wounded older brother was dying, his last words were “Find Inazuma.” But we didn’t know where he was from or anything else about him except that he was a medic in the Ishi Battalion. Just before leaving Ginowan in late March, he had told us, “The battalion is being transferred, I don’t know where, so I won’t be seeing you for a while.” But we never saw him again.

We try asking the army for help finding Father

On April 1, 1945 the U.S. military landed on Okinawa Main Island. We didn’t know about this, or that earlier, on March 26, they had landed offshore in the Kerama Islands. But we knew the war was going badly and vowed, if the time came, “Let us all die together.” Grandfather wanted desperately to see his two sons once more, so we decided to go search for them in the army.

We heard that army headquarters was in Shuri. There we hoped to find out the location of the field hospital where we might learn their whereabouts. We knew this was grasping at straws, but set out for the city anyway, creeping low along the road at night with artillery shells flying overhead, and arrived late the next day. (It wouldn’t take that long today.)

Under heavy assault by the U.S. military, Shuri had become a battleground worse than anything we had imagined. Well aware that Shuri Castle was Japanese army headquarters, the Americans were targeting it relentlessly with continuous shelling. When we arrived, the castle had burned to the ground, its walls collapsed, its siding stripped, the trees around it in cinders, its red roof tiles scattered in pieces, and its wooden statues burned to unrecognizable scraps. I will never forget the horrible sight of that historic castle town in ashes, the ground covered with shelling holes and shrapnel lying everywhere.

How, we wondered, would we ever find out about Father here? This seemed harder still when we asked a soldier for the location of the Tama Brigade and its field hospital. “What—are you spies?!” he barked back at us threateningly. Now we realized, with artillery shells falling everywhere, we had to find a place to shelter. Following others, we came to a large limestone cave where we joined hundreds of families huddled inside.

With each thunderous explosion from outside, adults fell into breathless silence and children trembled and screamed. Inside that cave everyone had to eat and defecate. The place reminded me of pictures of hell. But things soon got much worse. A few days later six or seven Japanese soldiers entered the cave. “The army needs this shelter for the decisive battle here,” they told us. “All civilians must leave by sundown.” No one among the hundreds of us complained or refused. This was, after all, ”our nation’s” decision and the army’s command at a time when everyone just followed orders with no objections.

That evening, as we were preparing to move, the grandmother who had raised me in place of my mother died suddenly without a word. It was suicide. This was the greatest shock of my young life. She was the grandmother who had decided that, if the time came, she would hold me in her arms so we’d die together. She was the grandmother who had thoroughly educated herself by reading; who had scolded me when I did something wrong. When I screamed, demanding to wear my dress kimono for New Years that had survived the firebombing of Naha, and to display the traditional emperor dolls on Girl’s Day in March, she made me understand that “As guests of the people here in Ginown, this is no time to dress up.” Instead, for New Years, she sewed monpe pantaloons with a quilted front piece using Kumejima kimono material; and, for Girls Day, she folded colored paper into dolls, and made cookies from potatoes, treating the neighborhood children, too. As an adult, I always thought of Grandmother as extremely wise. Our family ran a hospital and she knew a lot about medicines, so she must have gotten ahold of one she knew would kill her. She had decided to die because running from one place to another trying to escape the shelling must have become unbearable. Yet it still seems incredible to me that she should have died in silence without saying a word. I have no memory of what happened to her ashes.

After following army orders and leaving the cave, we were aghast at what we saw beyond the hills offshore. The ocean was covered with dozens of ships, seeming to surround the whole island. They were shooting streaks of fire with thunderous booms, sending out red arcs in the sky as explosions echoed far and near. This was “Kanpō-shageki,” naval bombardment. We learned later from accounts of the battle that the U.S. had amassed 1500 warships. As a child, I’d had no idea of the huge gap in war-fighting resources between the U.S. and a Japan where housewives in “Women’s National Defense Associations” practiced with bamboo spears to fight American soldiers. “Those are enemy gunboats,” the Japanese soldiers told us. “Their forces will attack here. You must leave now for the northern region!” But hearing no news from Father and determined to find him, our family ignored the soldiers’ instructions and headed south from Shuri in the pouring rain. We struggled to make our way along farm roads where our feet sank in the mud with every step. Ordinarily the crybaby of the family, I had somehow forgotten to cry. Holding my six-year-old little cousin’s hand, I put all my strength into trudging behind the adults who carried our belongings. At Tsukayama every cave was overflowing with refugees all jammed together, so there was no room for us. We sat down to rest at the entrance to a cave, shivering and dripping wet in the cold that felt like winter.

The enemy’s shelling got much worse at dawn, so it was impossible for us to move during the day. Huge airplanes dropped bombs from the sky, warship cannons fired from the sea, and–even more frightening–small Grumman fighter planes swooped low directly over us and the roofs of nearby homes. Their machine guns could shoot hundreds of bullets at anyone or anything they aimed at on the ground. Grumman formations flew in at dawn and fired their guns throughout the day, returning to aircraft carriers at dusk, so we spent our days waiting with bated breath for nightfall. But, even at night, the shelling never stopped. Flares lit up the sky, firebombs burned down homes, shrapnel flew, and tanks fired shells and flame-throwers. At dusk, just after the terrifying Grummans returned to their carriers, was the one short time we had to look for the next place to shelter. We sloshed along roads muddy as wet rice fields and, with the sound of shells exploding nearby, even my little seven-year-old brother knew, without the adults telling him, to dive into a ditch or squeeze up beside a rock. After a few days we arrived behind the Kochinda National Elementary School where the local people had dug several underground shelters into a hillside. Although the Japanese army was using the one in the middle as a field hospital, there was still some room in the others, so we had finally found a safe place. But now all the food we brought with us had run out. My aunt Tsuru left the shelter to find food, risking her life in the shelling. After Grandmother’s death, she must have felt totally responsible for the elderly family members and us children. How terrifying it must have been to dig up potatoes with shells falling all around! It pains my heart today remembering how she had gone all-out to save us, ignoring the danger to her own life. We waited for her return to the shelter so worried we could hardly breathe. It made us all the more grateful for the one meal we ate each day.

My beloved older brother dies in the shelling

At Kochinda, after the Grummans stopped flying at dusk, we would leave the stale hot and humid air inside the shelter to breathe the fresh air outside and stretch our limbs. One evening, as usual, we were outside with other evacuee families enjoying the cool breeze. Of course, our nerves were on edge, seeing shrapnel on the ground and hearing bombs explode, well-aware of the danger all around us.

Then suddenly a shell exploded, though I couldn’t tell if it had fallen nearby or directly among us. It happened so fast I didn’t have time to lie down flat on the ground, as we’d been trained, and could only cover my face with my hands as my body tensed. In the strange quiet that followed, I nervously opened my eyes to a scene of carnage so shocking I couldn’t move, even to rush back to the shelter only two meters away. Hit by shrapnel were people on the ground unable to get up or who struggled to stand. Others, covered with blood, ran for the shelter. Among them I saw my brother, bleeding from his chest. Thinking I too had been wounded, I followed him, but after only a few steps I stumbled over something. At my feet was a boy I knew well, about my age, who I’d just been chatting with moments before, now lying on the ground. I could see that part of his head had been blown off, and that he was dead. Though shocked at the sight, I stepped over his body and hurried to be with my brother.

The shrapnel had torn open a deep wound from his shoulder down his side leaving only shreds of skin remaining. He still had his arm on that side, but couldn’t move it, so was using his other arm. Seeing him like this, I nearly passed out. Then, through my tears, I asked him if it hurt. “No, I’ll be fine,” he answered emphatically, though I knew he was in terrible pain. I wanted so much to help him, but had no idea what to do. Soon a stretcher arrived from the army field hospital, and he was carried there. I had no way of knowing how many were killed or wounded in the shelling. Until then my brother, younger sister and I had been visiting the field hospital for any news of my father, and become friendly with the army doctors and nurses.

Under battlefield conditions with meagre medical equipment, full treatment was impossible, but the doctors and nurses provided the best possible care and emotional support. Or, at least I wanted to think so. My brother’s left arm was amputated. I did not see the surgery, but watched as he was carried out on a wooden board with one arm missing and a blood-stained bandage wrap. Seeing that his wound still bled profusely, I began to lose hope. “Water, give me water!” he yelled, screaming in pain. Soon his breathing stopped. Standing beside his corpse, I apologized, wishing now I had given him all the water he’d wanted. He was only fourteen, going to school where all the students served as laborers for the military, and just happened to be home with his family when the Americans invaded on April 1, 1945.

Everyone admired him as a youth of great promise, highly intelligent and as well-read as any adult. He especially liked chemistry and often ran experiments. Once, when I was helping him, I got burned by one of the chemicals. I can say for sure—and not just because he was my brother–that he would have achieved great things in life had there been no war. Although we were brother and sister, it seemed natural that there was a huge gap between us. I felt great pride in him, the one for whom our family had the highest expectations. At age fourteen he was in the second year of middle school, and had been especially kind to me. In the shelter he’d passed me some pieces of brown sugar even after Grandmother said I couldn’t have any. “This is all I’ve got,” he’d said. “Keep this our secret.” To lose him so suddenly plunged me into unbearable loneliness. Only the vague thought that, before long, I would be rejoining our family kept me going.

My grandparents, too, were devastated by the death of my brother who had carried so many of the family’s hopes for the future. In our despondency we seemed to lose the strength to continue searching for Father, and I stopped eating. I remember Grandfather scolding me for refusing the precious food my aunt risked her life to bring us. Gradually, I got thinner and my body weakened.

We move farther south into an area of heavy ground combat

The day after my brother’s death we heard that a nearby shelter was attacked with a flame-thrower killing all the evacuees inside. And, since the army field hospital had pulled out, we decided to leave the shelter at Kochinda.

Flame-throwers weren’t weapons dropped from airplanes or fired from gunboats, but sprayed from tanks or by soldiers carrying canisters and hoses. So we knew that the enemy must be nearby. Our family hated to leave the shelter we’d had so much trouble finding without even knowing whether we’d find another one, but couldn’t stay in a place where we might soon be burned alive.

The movement of Japanese army field hospitals during the Battle of Okinawa had tragic consequences. Lacking the manpower to carry severely wounded soldiers on stretchers, only those who could walk went with the unit. The rest were left behind, though they pleaded not to be abandoned. Some might have a potato or one rice ball while others had nothing to eat. Each was given a dose of poison and a cup of milk so they could kill themselves to avoid capture by the enemy. We heard from the adults speaking in low whispers about what the enemy did to prisoners of war. The “devil-beast Americans” would slice them up into little pieces, they said. We firmly believed this, which was why the disabled soldiers took poison, and why we had to leave the shelter.

The area outside the shelter was littered with shrapnel fragments. Mortar shells had gouged holes in the ground that filled with muddy water, and in some of them corpses floated.

After leaving the shelter we saw the horror of a losing war. Corpses everywhere—along farm roads and in the fields. Some were black and swollen. Others stank from rotting in the hot summer sun. In some places they were lying one upon another. And there were wounded who couldn’t walk and small children sitting on the ground who had lost their parents. With no means of treatment, the injured spread lard mixed with salt on their wounds. Maggots swarmed over the dead. The injured, lacking medicine, disinfectant or bandages, tried desperately to brush maggots off the decaying flesh of their infected wounds. For us, after leaving Kochinda, there were no shelters or caves. Even when we found one, we were told it was already full of soldiers and civilians. We pleaded to be let in, but the soldiers yelled “Get out of here! Don’t hang around or the enemy will spot you and make us a target.” Nowadays, inside those caves is said to have been “a hell on earth,” but as the only place we could feel safe from the shelling, it seemed like “heaven” at the time. In that part of southern Okinawa, hundreds of thousands of civilian evacuees sought shelter in caves that were “army priority.” Many ended up wandering desperately in groups on the roads only to die in the shelling and become piles of corpses.

Above all I didn’t want to become one of the severely wounded. I knew, if I died, I would be spared their horrible suffering. No way would I pray to God to save my life! I was resolved to die, but not after days of writhing in pain from a rotting shrapnel wound infested with maggots. Thus, at age ten, I began praying to God for a quick death.

During this time we saw no Grummans, but shellfire crisscrossed overhead threatening us day and night. We managed to survive by dodging behind rocks or in the ruins of barns and farmhouses. Unlike children of today, I knew little about Okinawa’s geography or terrain. Fleeing the battle from north, south, east and west, people with no place to go crowded into this one corner of the Southern District wandering aimlessly like sleepwalkers in the dark of night. Did they think, if they just kept moving, they would find safety somewhere just ahead? Even for me, a ten-year-old child, this seemed pointless. With shells exploding all around, as soon as they heard another explosion, they would take off running.

Day after day with no let-up in the shelling and no clue to Father’s whereabouts, we lost our resolve to look for him as we pushed on to escape the inferno. Even as the onslaught worsened, Okinawans believed that, if they could just endure a little longer, a huge force of support troops from mainland Japan would be coming to their rescue. To this day I have been unable to stop remembering the extremes of horror I witnessed then.

Moving by night in search of a shelter, we came under heavy enemy fire and dropped down for cover. As usual, when it let up, we checked with each other to make sure everyone was all right. Our family was safe, but a woman we didn’t know who’d begun traveling with us had fallen into a shell hole just gouged in the ground. She was screaming and writhing in pain. “My daughter is waiting for me in the forest. Take me to her!” she begged. Then we saw she had lost both her legs. We all felt sorry for her, yet by this time no one had the strength or will to do anything but save themselves, not even to help her out of that shell hole. A Japanese soldier who just happened to be passing by lifted her legless body onto his back, and resumed walking using his army sword to hold her in place. Shredded pieces of flesh and gobs of blood fell from her torso, staining his uniform and gaiters a dark red. She continued saying that her daughter was waiting in the forest as the soldier carried her along until she fell unconscious and stopped breathing. It must have given her comfort, as she rode on that soldier’s back, to hope that she would be able to see her daughter again.

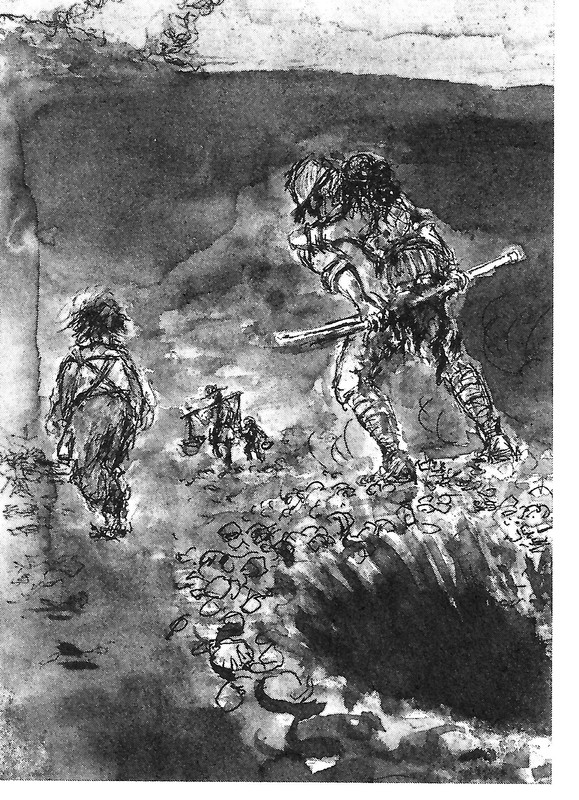

|

A woman who lost her legs is carried by a Japanese soldier. |

His was a beautiful expression of humanity on the battlefield. Today I wonder what prefecture he was from. Was he able to survive war’s devastation and live to see it end? How many precious young lives did this war cut short—of soldiers with such noble spirits and of students drafted into the army? With their talents just beginning to bloom, they must have dreamt of bright futures.

As more soldiers got separated from their units, they mixed in with the civilians heading south. Some acted arrogantly, taking their frustration out on civilians; others who had deserted the fighting put on farmers’ clothing over their uniforms to disguise themselves as civilians; and some soldiers snatched potatoes from the hands of children. Having lost their humanity in the terror of battle, they were hardly the valiant warriors we were supposed to rely on for protection. Yet, looking back today, we cannot condemn them. They were also the nation’s victims with families—devoted parents and siblings– waiting for them anxiously at home, praying for their safe return.

The grandfather we all relied on is wounded by gunfire and kills himself

Moving on unfamiliar roads with strangers who went their separate ways, I did not learn until after the war where our family had ended up. It was in the Southern District where we stopped in the village of Makabe at a small, thatched-roof farm house. We knew it was too small to hide us from the artillery fire and Grumman fighter plane attacks that started at dawn. We’d hoped to find another cave like the one at Kochinda where at least the Grumman pilots couldn’t see us. Here our family of six could only try to protect ourselves crowding together with one tattered blanket over our heads. I sat on Grandfather’s lap cuddled in his arms. Starting before dawn that day, the relentless shell fire got so bad we were afraid to move. Then I heard Grandfather moan. Lifting the blanket, I saw he had been hit by shrapnel with blood streaming from a gash that ran from his back around his left side. I was unhurt. It seemed that grandfather had protected me by shielding me on his lap, and gotten gravely wounded himself. Now we all fell deeper into despair. Not wanting us to see him, Grandfather had the family move us children behind a nearby stone fence. We could still hear his voice, though. Terrified, we grasped each other’s hands so tightly they hurt. Then we heard a sound that seemed not of this world, his final cry of death.

Later my uncle told me that Grandfather, bleeding profusely and not wanting to be a burden to the family, had killed himself. I couldn’t stop crying, thinking how much he must have suffered. If only his son, a doctor, had been there to treat his wound! This was the world of war where all human efforts, determination, and endurance come to nothing.

That Grandfather, whose kindness and honesty was an inspiration to all of us, should die this way was proof, I thought, that there was no God.

I learned later that the adults had previously agreed they would kill themselves if they were gravely wounded and couldn’t walk. This was both for the sake of the family, and for the wounded who would quickly end their suffering when death was inevitable. Grandfather had been the first to act on this agreement.

He had been a farmer and raised many children. His oldest son, my father, had excelled in school, and was recommended for medical college by the principal, Shikiya Kōshin. It was thanks to the high value Grandfather placed on education that my father became a doctor, an enormous achievement at the time.

We left the remains of our beloved grandfather where he had died, and set out again among strangers. We had no destination in mind, but couldn’t stay where we were, so we resumed our wandering in search of a place that would provide at least some shelter. Everywhere on farm roads and in fields lay corpses amidst the stench of death. Seeing dead and wounded without arms and legs, with heads blown off, or with intestines protruding sent waves of fear through me. Grandfather’s death had convinced me there was no God, yet I now prayed to God again for a quick death.

I get trapped under a fallen house.

To our surprise we found a house with tiled roof that had partly survived the inferno of shells and bombs, though the walls and floor were gone. We joined other evacuees crowded inside, but this only lasted for one night. A huge bomb fell in the field behind it and, although there was no fire, the house collapsed in the blast from the explosion. We had barely escaped a direct hit, but I didn’t get out in time and was buried under the rubble. I yelled loudly for help, but couldn’t tell if anyone heard me. My small body was stuck under a heap of broken tiles. I had no idea whether my family was safe, or even if I’d been hurt. Above, I could hear people walking, and thought they must be searching for me. I yelled out again as loud as I could. At last, after what seemed like a very long time, I was rescued by my uncle and an army civilian worker. My uncle seemed on the verge of tears as he checked my head, shoulders, arms and legs to make sure I wasn’t hurt, and then, greatly relieved, hugged me tightly. It seemed like a miracle I’d escaped injury.

The blast had killed or injured most of the other nearby evacuees. It was early afternoon so, as usual, the Grummans were crisscrossing low overhead. With everyone confused about where to go next, my aunt grabbed my hand and we headed for the storage shed where her children and Grandmother were waiting. It was then I saw a boy about my age looking totally bewildered as he lay with his back against the crumbling stone front gate. His neck covered with blood from a shrapnel wound, he propped up his head with one arm. He seemed lacking the strength even to cry. Surely, he must have lost his parents in the bomb blast. Everywhere I looked there were dead and wounded, and everyone else knew they could be next. I continued praying for a quick death.

Shellfire kills Grandmother instantly and wounds my aunt and cousins

For the next several days we took cover wherever we could during daylight hours, and walked around searching for a cave shelter at night. My memory of this time is very hazy. I cannot remember eating anything. With no hope of seeing Father again, I was exhausted in body and mind. I had resolved to die, and avoid the suffering of a wound that could tear my arms and legs into blood-spurting shreds. And I wondered, does a war ever end?

Refused entry into the few cave shelters we found, we ended up taking cover in one of the groves of umbrella pine trees that grew in the fields. Here we thought we could hide from the Grummans when we stayed still and put the tattered blanket over our heads. We saw no one else around. All we could hear were the drone of bombers high in the sky, the roar of low-flying Gummans, and the explosions of shellfire. I curled up tightly trembling in fear. Even today I shudder to remember how we were trapped in that assault on the Kyan Peninsula. This was where, when he knew the battle was lost, General Ushijima, the commander of Japanese forces, killed himself at the foot of Mabuni Hill.

Fleeing from place to place on the battlefield, we became all-too-familiar with the sounds of shells firing and detonating far and near. One day in the umbrella pine grove there was a blinding flash of light and a roar so loud it seemed to envelop my body. Stunned, I felt my head swelling and pressure on my ears. I don’t know how much time passed before I came to my senses. Then, as before, I threw off the blanket and turned to see if my family was all right. The tree leaves over us had been blown away exposing the blue sky. I called over to my grandmother, but there was no answer, even when I shook her. I could see no wounds, but she had stopped breathing. I saw that she had died instantly, and envied her for being so lucky. Death without suffering was what I had prayed for myself. I began feeling this envy after my wounded grandfather’s courageous suicide. After that, surrounded by war’s devastation, Grandmother had apparently stopped speaking, and I realized now I had not heard her voice in a long time. My younger cousins beside me were crying out weakly in pain. “Where does it hurt,” I asked, but they couldn’t tell me and only continued sobbing. “I can’t move either,” said my aunt, gasping for breath. “You’ve got to get out of here, Rieko. Go!” she insisted. I was too exhausted to think whether it was better to face the fear of fleeing alone or stay with the others. Propelled by her words, I ran from the grove.

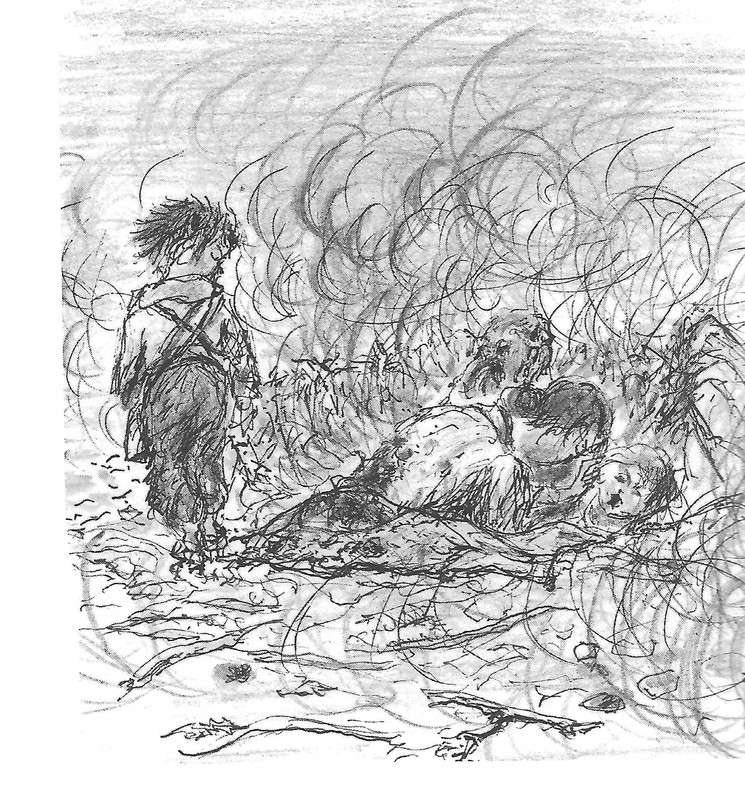

|

Rieko, her wounded aunt and cousin |

Walking alone at age ten through war’s inferno.

I looked around for someone—anyone—who might be sheltering behind rocks. Surely, everyone must have taken cover from the relentless rain of shells. But there was no one in sight, and I had the gruesome illusion that everyone in Okinawa had died. By this time my shoes were in tatters. After months of fleeing through the rain and mud, the soles had peeled off. I had managed, with a child’s resourcefulness, to tie the soles back on using bandages and rags so the shoes wouldn’t slip off my feet. Still, it was hard to drag them along as I walked, taking cover behind rocks and beside susuki trees. Without the means or strength to look for father and with fear rioting inside me, I was desperate to find someone—anyone.

I had lost my father and uncle to the draft, my two grandfathers to suicide, and my grandmother and older brother to shellfire. I had abandoned my aunt and little cousins as they lay dying. Now I was wandering aimlessly through a battlefield on what seemed like the longest day of my life. Then, just as the sun was finally setting in the sky, I spotted some people up ahead, and they were alive! I ran toward them as fast as I could, careful not to step on the shrapnel or corpses. When I reached them, I could see they were a man and a woman in civilian army work clothes with a young girl about my age. “Are you alone?” they asked. Even before bothering to introduce ourselves, they welcomed me to join them. I can remember that, after the Grummans stopped flying at dusk, we began looking for some place to shelter. The best we could find was a large rock. We sat down beside it and were immediately surrounded by the stench of death from nearby corpses that soon became unbearable. Next thing I knew the man was passing around Japanese army hand grenades to each of us. It felt very heavy in my hand. Thinking this was how I could die whenever I decided, I received it from him gratefully, like some valuable treasure, and placed it in my first aid pouch. I realize now that I didn’t have the slightest idea how to use it. I have no memory of the four of us eating anything, but can’t remember being hungry either. I seemed to have forgotten about eating, and wonder now how many days it would have been before I starved to death. Anyway, somehow I survived. Maybe my nerves stimulated by fear kept me alive.

The next morning we realized there were no Grumman assault planes overhead. The big bombers were still flying and the warships firing their guns, but all the shells were bursting far away, and nowhere near us. We felt relieved, but it also seemed weird. We looked around thinking there might be enemy soldiers nearby. Then, cautiously, fearfully, we stepped out from behind the rock. The man set out low-crawling, as quietly as possible, to the top of a nearby hill.

“Hey,” he yelled down to us. “The war’s over, folks!” Was this true, I wondered. Was it really over? By this time I’d lost the strength to wish it would end, or even to think wars ever ended. Now the rest of us scrambled up the hill to look around. From every corner of the land huge crowds of refugees in tattered rags were streaming in one direction. What I saw seemed incredible, and for a moment I thought I was dreaming. How could the war be over, I wondered again, never imagining that it could end with Japan’s defeat. After all, we’d been taught that Japan was “the land of the gods,” and no matter how desperate the situation might be, the kamikaze winds would blow and bring the nation victory. Anyway, I couldn’t believe all these people were still alive. Where had they been hiding? Now I could fully appreciate how many lives Okinawa’s cave shelters had saved.

|

The battle ends |

Soon the four of us joined the crowd in tattered rags heading in one direction. After the many days staying in dark places to take cover, the dazzling midsummer sunlight made me dizzy reflecting off bare rocks denuded of surrounding plants and trees. Walking together with the other refugees, I had never seen people with skin so red or black. What I noticed most was how their teeth and eyeballs gleamed white in their dark faces. Soon we encountered American soldiers for the first time. I watched mesmerized as their company passed beside us shouldering rifles and walking in formation. Now I knew for sure that Japan had lost the war.

We were assembled in an open field and sprayed from head to toe with DDT. After months under the scorching sun or in hot and humid caves without changing clothes or bathing, we were caked with sweat and dirt. This spraying is how we were disinfected of fleas and lice after many hours walking. Though liberated from the terror of shellfire, we had no idea what was going to happen to us. I was surrounded by strangers, but since there were so many of us, I didn’t feel we were in danger.

A miraculous meeting

I can’t remember how far we walked after that, but when we reached Hyakuna in the town of Tamagusuku, Mr. Kyota, the mayor of Kakazu who had helped us find a place to stay in Ginowan, came running out of the crowd of refugees and hugged me. ”Rieko, are you OK? How about your family?” Feeling as though a god had rescued me from hell, I clung tightly to him. Thanks to Mr. Kyota, instead of going to a refugee camp for orphans, this god took care of me. In the days that followed he also escorted other people he knew out of the long lines of passing refugees and placed them all—more than sixty—in a large tent shelter. Everyone there was especially kind to me, an orphan who had lost her family. I even went to a “school,” which was really just a plywood board hung from a pine tree where I first learned the English A-B-C’s. That outdoor school was fun for me as a fifth grader.

With nothing to wear but the clothes on our backs, we washed them in a nearby stream and, while they dried on the grassy bank, we played in the water. Mrs. Kyota was sure I had a change of clothes in the first aid bag I was using as a pillow, and insisted I wear them. So I opened the bag to show her there were no clothes. Inside was that hand grenade! Greatly alarmed, Mr. Kyota snatched the bag from me and ran carrying it away from us in a hurry.

It was the time when children would gather around the Americans’ jeeps yelling “gibu me kyandii.” Though a child myself, I quietly vowed not to eat the candy or chew the gum they handed out. We received food rations from the American army, and the adults found lots of potatoes, pumpkins and melons abandoned during the battle in nearby fields. They were some of the biggest I’d ever seen, weighing dozens of kilos. We called them “ghost potatoes” and “ghost squash” because they grew abundantly in the ground under black leaves where there were also human bones. Earlier, during the battle when the shell explosions were far away, American soldiers led groups of refugees into the fields to dig up potatoes.

One day the adults went out to dig potatoes and I was left to look after the small children. All at once a man I recognized came running up to me and, without saying a word, grasped my hand tightly and pulled me out to the wide road. Then he hoisted me up into the back of a truck where a woman grabbed me in her arms. It was my father’s younger sister, Aunt Chiyo! Astonished at first, I felt joy and a profound relief. After the horrors I had endured alone for so long, I burst into tears sobbing my heart out in her loving arms.

Aunt Chiyo was being held in the refugee camp at Yanbaru when she decided to take a big risk and, with no particular destination in mind, jumped into the back of an American army truck heading south. At the time most areas outside the camps were still “off-limits,” separated by roadblocks, so traveling between northern and southern Okinawa was nearly impossible. Riding in the same army truck into the southern district refugee camp, the man had recognized Aunt Chiyo because they were from the same town, and decided, on the spur of the moment, to rescue her niece–me. My reunion with her was truly dramatic, and can only be called a miracle. Back when Chiyo’s older brother, my father, had entered medical college, she abandoned her own plans to attend women’s higher school so she could earn money for his college expenses. Never expressing the slightest regret for this decision, she felt only the greatest love and respect for her brother and pride in his achievements.

I was taken then to the refugee camp at Sokei in Yanbaru where several of my relatives were held. As they hugged me in our tearful reunions, I could hardly believe some of them had managed to stay alive. I’d been sure my aunt Tsuru, gravely wounded when we left her at the umbrella pine grove, would die, but here she was having somehow survived! It seemed like a dream. Her back was bent so she had to walk with a cane and her shaved head was wrapped in a kerchief. She was only twenty-six at the time, but, all shriveled up, she looked more like eighty. Seeing her this way was a shock that left me speechless and unable to stop crying. I remembered how she had risked her life alone in the midst of shellfire to leave the shelter and gather food for our family. Hers was a truly noble heart.

Aunt Tsuru told me she was barely consciousness when she found herself in an American army truck. She had apparently been picked up with her children. Losing consciousness again for several days, she awoke the next time in a bed at an army field hospital. As soon as she was able to walk with a cane, she searched among the many wounded patients for her son and daughter, but could not find them.

The war ends and my uncles return home.

Some time later, with the reopening of some civilian areas, we were able to go back to my grandparents’ hometown of Gushikawa. And, in more good fortune, Father’s younger brother Yoshiharu returned from the Japanese army air corps in Tokorozawa, Saitama Prefecture along with Mother’s younger brother Isamu from Australia. I thought about how war had taken the lives of my whole family, but these two uncles were spared.

Uncle Yoshiharu, barely eight years older than me, was the one who cared for me just after the war. It was a time when everyone was desperately poor, but with my two aunts’ helping us, I was raised in an abundance of love.

As other civilian areas reopened, we were able to collect the remains of my older brother and grandmother, but could find none for the others. We never learned where my father, a medical corps officer, or Uncle Yoshihiko, an army infantryman, had died. We received only a faded Japanese army notice of Father’s “death in battle on June 19th, 1945 in the Kyan area,” and a postcard stamped “combat death notification” for his younger brother Yoshihiko in the local infantry. As the only one in our family of ten who had miraculously survived without injury, I felt it was my duty to assign death dates for my older brother and grandfather estimating from my hazy memory of events. Each died without knowing of the other’s death, which at least spared them from grief.

At a time of militarism, emperor supremacy, and “education to be imperial subjects,” many Japanese felt discontent and anger, but could not speak of it. All protest was brutally suppressed. Then, with defeat in the war, people were suddenly liberated. Nowadays, individuals can sue the government for injustices, something that would have been unimaginable before.

Having followed the road to World War II defeat, Japan finally awakened. The people vowed never again to wage war and devoted their efforts to economic recovery and democratization, creating a nation of peace and material abundance that has placed Japan among the world’s great economic powers. Defeat in war brought the curtain down on the brutally militaristic society, and Japanese now have freedom of speech.

Yet conflicts persist in many places with chances remote for a world at peace. The scars of war are slow to heal, and clashes break out constantly. The number of people like me who grieve the loss of their families is countless. Still, we must advocate for peace.

I am deeply grateful that I lived to see Japanese enjoy the blessings of “freedom” today. But Japan remains at risk. We hate war that robbed us of our families and ruined our lives, but where should we aim our anger—at the nation, the emperor, government leaders of the time who’ve been executed as war criminals?

Everyone wants “true peace.” But it is not enough simply to wish that our grandparents, uncles, brothers and sisters—all those who died in the war—could have lived in this time when shells aren’t exploding and there is freedom of speech. We can’t just bemoan the past calamity. No matter how much government leaders blunder or what the circumstances are, we must never forget to revere the preciousness of human life.

The most important principle of education is to teach this reverence for life that is the source of our humanity. And this principle must be fully embraced by statesmen and teachers alike. In this way, when there is conflict between nations, it will not take thousands of precious lives.

As we approach the fiftieth anniversary of war’s end, we must remind ourselves again of this principle, and Okinawa, with lessons learned from the last war, must send a message for world peace. For history to stay on this righteous path would be a true requiem to the many victims of that war.

Tamaki Rieko (néé Sakai)

Heisei 7 (1995)

Summer

AFTERWORD

Though I lack writing skills, I was determined to record my memory of those days filled with terror that I cannot forget even if I try. Such things must never happen again. Today they remain all-too-vividly in my mind. Perhaps it was because I was a small child that they made such a deep impression, though I have trouble remembering dates and place names for what I might call “Memories from when I was age ten:”

“I want to tell you, my young cousins born after the war, about your grandparents, uncles, and older cousins. They were born into an age when war took their lives, so you never knew them. I want you to know what it was like for them, trapped on that battlefield.”

I emphasize that this is what happened to my family, and that experiences vary among those who were caught in the heavy fighting in the Southern District. They were soldiers defending their nation, home guards attached to the military, middle school boys in the “Emperor’s Iron and Blood Student Corps,” and girl students in the “Women’s Volunteer Corps.” Among the refugee families, students, teachers, and parents on the evacuee ship Tsushima-maru, more than 1700 died in a torpedo attack remembered as one of the war’s greatest tragedies. During the four months when Okinawa became a battlefield, more than 100,000 lost their lives, as many as died in one of the nuclear attacks. As in Okinawa, the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were forced to become victims. I want my young readers to understand that, trapped on a battlefield, all human efforts and determination are absolutely useless. You must not assume that peace and freedom are the natural state of things. I want you to fully appreciate the preciousness of life and convey this principle unadulterated to future generations. The war is over, and I have forgiven the enemy. I record these memories of how war devastates families because this must never be forgotten. I will never forget, or find relief, from my memories as long as I live.

A Postscript in 2004, Ten Years Later

Now war has started again [in Iraq]. Japan has sided with America, the instigator. Falsely labeling it “reconstruction assistance” and “humanitarian aid,” the Self-Defense Forces are sent into danger on battlefields. They smile facing the TV cameras, teeth clenched, reciting the words “We will carry out the mission.” Their families shed anxious tears as they see off their husbands, fathers, sons, and SDF women, too. The pride and reassurance Japanese felt vowing to renounce war—was it just a fleeting dream? Though proclaimed in our Constitution, this vow, flimsy as backyard gossip, is now crumbling before our eyes.

Already, this war has taken the lives of our countrymen—a diplomat and photographer. Why doesn’t Japan have the courage to say no and put down the guns? Italy and Spain refused, offering recovery aid, but decisively announcing their soldiers’ withdrawal.

Mass murder and destruction, the death of everything that lives, cultural legacies destroyed beyond recovery. Human stupidity endlessly repeating. In Okinawa the verdure, the buildings and the roads are beautifully restored. But lost lives don’t come back. There is no replacement for human life. How will Japan’s youth greet the future? Can Article Nine be preserved?

I say to all you young people, “It must be preserved—for your own sake.”

May, 2004. (Though having little influence, I convey this message.)

Related articles:

- Masako Shinjo Summers Robbins, “My Story: A Daughter Recalls the Battle of Okinawa”

-

Yoshiko Sakumoto Crandell, “Surviving the Battle of Okinawa: Memories of a Schoolgirl”

-

Ota Masahide, “Ryukyu Shimpo, Ota Masahide, Mark Ealey and Alastair McLauchlan, Descent Into Hell:The Battle of Okinawa”

-

Hirano Chizu, “In Love and War: Memories of the Battle of Okinawa”

-

Steve Rabson, “American Literature on the Battle of Okinawa and the Continuing US Military Presence”