Translated by Mieko Maeshiro

Introduction by Steve Rabson

Introduction

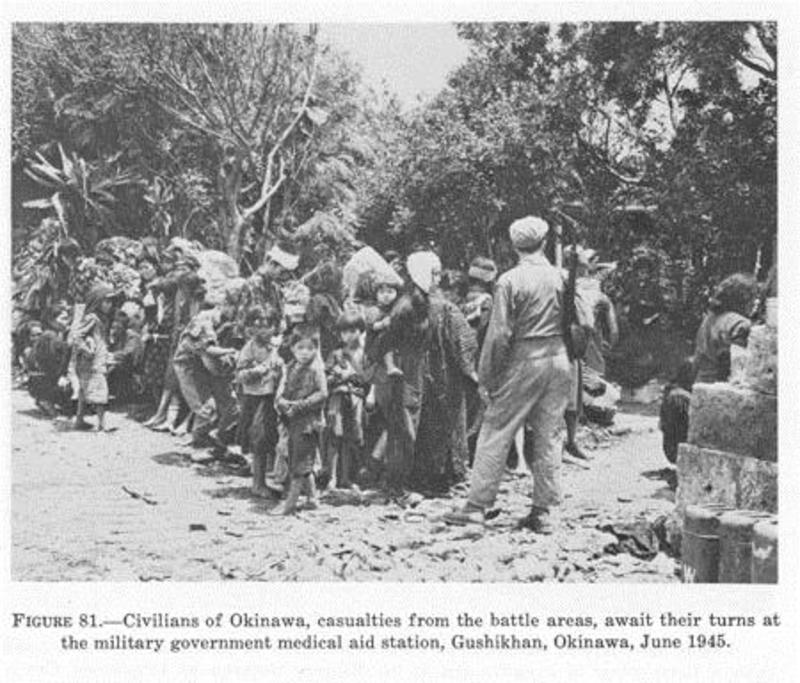

Below are translated excerpts from Yoshiko Sakumoto Crandell’s autobiography, Tumai Monogatari: Shōwa no Tamigusa (Tomari Story: My Life in the Showa Era), published by Shimpō Shuppan in 2002. The translation is by Mieko Maeshiro. Born in 1931, the 6th year of Shōwa, the author was raised in Okinawa’s famous port town of Tomari, a section of Naha City, the prefectural capital. Her father worked as a ship-builder and her mother made Panama hats, a major export from Okinawa at the time. The portion of her autobiography presented here describes her harrowing experiences during the Battle of Okinawa, in which she was wounded by shellfire and narrowly avoided rape by an American soldier. It concludes with her internment in a refugee camp during the battle’s chaotic aftermath. In the early months of the 27-year-long U.S. military occupation of Okinawa (1945-72), the author worked briefly for the American forces in food service and laundry, and later for the Ryukyu Life Insurance Company. In 1969 she married an American in the U.S. Air Force stationed in Okinawa. They live today in Newport News, Virginia.

Other accounts available in English of women’s experiences during and just after the battle are A Princess Lily of the Ryukyus by Jo Nobuko Martin (Shin-Nippon Kyōiku Tosho, Tokyo, 1984) on her service with other high school girls as a battlefield nurse; and interviews translated in Steve Rabson, The Okinawan Diaspora in Japan: Crossing the Borders Within (University of Hawaii Press, 2012), pp. 128-137.

Life in Okinawa Before the War

I was born on March 3rd in Shōwa 6 (1931) in Tomari, a section of Naha City, the capital of Okinawa, an island surrounded by coral reefs. When I was little, I often saw the bright sun setting on the horizon, a scene beautiful beyond description. The rippling waves made me want to play in the water like the fish. Those shiny silvery ripples under the bright sun dazzled my eyes. But winter made the blue ocean gray and brought a stiff, cold wind. Typhoons pounded the island regularly with the raging ocean beating the shore and splashing the wharf in a cloud of spray. It seemed

that, like humans, Mother Nature also possessed yin and yang.

At dusk after dinner, lights were lit in family dwellings. After the day’s work, the sound

of the sanshin (three string banjo-like instrument) resonated in the stillness of the evening. When my father started playing his sanshin, elders in our neighborhood tuned up their own instruments

and joined him. They played Ryukyuan classical as well as folk music. When I was in the second or third grade, I took Ryukyuan dance lessons. Sometimes I danced accompanied by my father’s sanshin music.

The sea in midsummer was cobalt blue and crystal clear. Boats came and went with the “pong-pong” sound of their diesel engines, the memory of which makes me yearn for times past. These boats were the only means of transportation between Okinawa’s main island and other islands, such as Miyako and Yaeyama. Yanbaru junk boats with huge brown patchwork sails filled with wind set out from the port. They went to villages in Yanbaru, the northern part of Okinawa. Some days later they returned with cargoes of firewood and charcoal, which were offloaded and piled up by the wharf. When the boats arrived, neighborhood children crowded the area. Among the bundles of firewood, we searched for garaki (rosewood) that had the smell of cinnamon and we peeled the bark to suck the spicy sweet juice. These were one of the few entertainments for us little girls who wore our hair in the Dutch-cut style.

Deigo (tiger’s claw) flowers captivated our eyes with their passionately red tropical color. The deep blue sky and splendid crimson of deigo (also: Indian coral bean) presented a spectacular contrast, along with the deep green leaves of cycad ferns and banyan trees that maintained their color throughout the year on this subtropical island. The red hibiscus flowers were the symbol of our home prefecture. In Japanese they are called bussoge (literally, “Buddha’s mulberry flowers.”) When we visited our ancestral tombs, we picked them from hedges.

|

Tomari, Naha and vicinity |

Tomari consisted of Maejima, Kaneku, and Shinyashiki (new district), Meimichi (the front

street), Kushimichi (the back street), Gakkōnume (in front of school), and Sōgenji (Sōgen Temple). The residents were united by esprit de corps, and local patriotism. “Ii sogwachi de yaibiiru” (Happy New Year) is the New Year’s greeting in Okinawan language. People visited their relatives and adults sipping sake to celebrate the New Year. Next came March 3rd. In the past, families went to a beach with boxed food, but this was no longer practiced. Instead we celebrated the day with March 3rd sweets (square-shaped donuts). Born on the 3rd of March, I had thought the special dishes were made for my birthday. When I discovered that every family made them, and that they were not just for me, I was disappointed and a little embarrassed.

The March 3rd celebration was followed by the Yukka nu hii festival on May 4th by the lunar calendar. My mother cooked wheat and red beans with sugar, and added rice dumplings. We called them amagashi (sweets). Another sweet delicacy my mother made was the pancake-like “chinpin” and “po-po.” Life at that time was simple, but we were never short of joyful events. When Yukka nu hii arrived, stores displayed various toys, and shop owners welcomed children with big smiles hoping that their parents would buy them toys. We felt like we were in heaven. Girls received colorful bouncing rubber balls decorated with painted flowers. They were the most popular toys and almost all girls had their parents buy them. Boys’ favorite toys were swords, tops and gittcho sticks. My brother loved swords. He always had a difficult time selecting one among the many sold at stores.

Yukka nu hii also brought haarii, the “dragon boat races” of fishing canoes to Tomari.

This was also the festival for fishermen to pray for good catches. The dugout canoes were decorated with dragons in bright colors. Crew members for each canoe included an oarsman, a flag bearer, a helmsman, and a coxswain who beat on a metal drum. My mother told me that people had to pay for reserved seats along the river banks from Tomari Bridge to the Tomari Port. When the race started, men, women and children all cheered for their favorite canoe teams. Some whistled through their fingers. The crew members wearing special team uniforms gave their all to reach a marked half-way point and then return to the finish line, rowing, striking the metal drums, waving banners, and chanting ”sa sa sa hai hai hai.”

Tomari is also known for its unique ji-barii, (land races of canoes on wheels). The crew

members paraded through the neighborhood streets in a boat-shaped structure as if they were rowing on the ocean. Before the event, they practiced at a neighborhood park or at my family boatyard. My father, as ji-barii team captain, trained crews when the ji-barii season approached. My best friend Kikuko’s father, Mr. Arume, was the only person who could sing the traditional ji-barii song in Chinese. I was fascinated by this strange song, whose words I did not understand. Boys played the gittcho game with two sticks, one shorter than the other. At the sound of a bell, began hitting the shorter stick with the longer one. The boy who hits the shorter stick farthest is the winner.

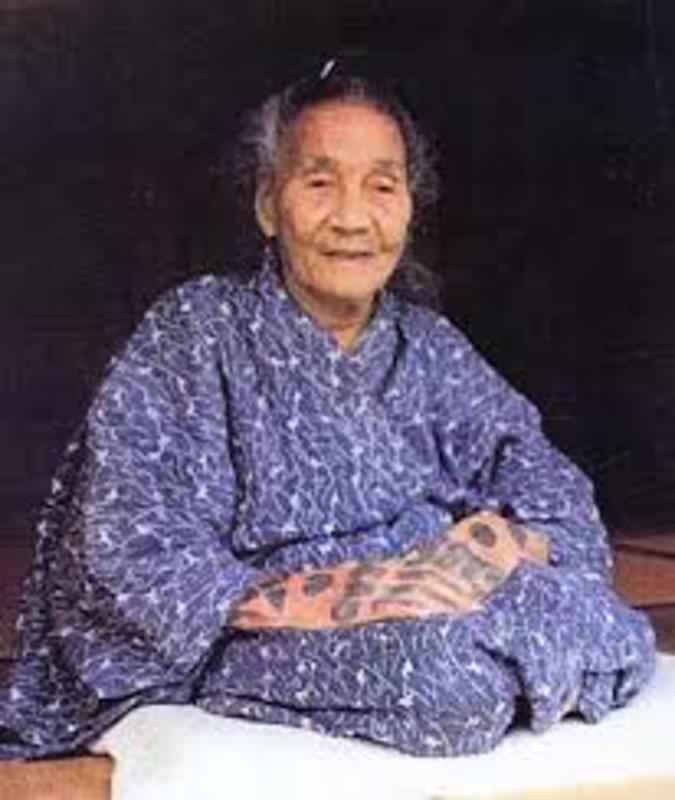

I remember my grandfather as a formal man. He was tall, handsome, and dignified-looking. His gentle eyes gave the impression that he was also very methodical. He talked slowly and politely. On the other hand, my grandmother was short and happy-go-lucky. We often laughed at her absent-mindedness. She was born around 1868, the beginning of the Meiji Era. Her skin was fair and her hands were covered with blue hajichi (tattoos). We grandchildren were fascinated by them. Girls received tattoos when they reached seven or eight years of age. Tattooing was a kind of fashion or status symbol among Okinawan women who competed for the most attractively tattooed hands, saying with a touch of envy that so and so “has beautiful tattoos.”

|

Tattoed hands |

Tattoos are now in style worldwide. Getting tattoos in those days required enormous courage. Girls went to tattoo artists with their friends or aunts with special dishes in lacquered lunch boxes. First, designs were drawn on their hands with a rubbing stick dipped in sumi India ink and awamori brandy. Then the artist inscribed the tattoos with from three to twenty-five needles bundled together while wiping away the blood. Friends who accompanied the girl kept talking to her to distract her from the pain. It took four or five visits to complete the process on both hands. Girls endured the pain in order to be fashionable, but on the fingers near the fingernails, it was almost unbearable.

Tattooing was the rite of passage to womanhood. It was said, “No tattoos, no admittance to the next world,” and “You cannot take your money after you die, but tattoos will stay with you into the next world.” Thus the custom may have had religious significance. The higher a girl’s social status, the more slender were her tattoo designs.

People in those days were very polite and bowed low when they greeted one another. I grew up watching my parents, especially my mother, carrying on conversations with her father or greeting him with very polite manners. It seemed that for my grandfather and mother good manners were extremely important. With all that low bowing, it was like watching a classical drama, and I always felt a little embarrassed. My grandfather lived near the Shuri Castle in Shuri, the old capital of the Ryukyu Kingdom. He owned a general grain store. The descendants of the Shō family (kings of the Ryukyus) were living nearby, and my grandmother took me to visit them. Grandfather visited us in Tomari once or twice a month after he finished his business in the city. When he visited, my mother knelt on tatami and bowed to him very deeply. My grandfather also bowed, and asked her how she was doing. I sat close to my mother and cast an upward glance. I heard that when he came to visit, our neighbors peeked through the fence. They were fascinated by their formal manners.

I learned about our neighbors “peeping” one summer evening under a banyan tree. Women came to the tree to enjoy the evening cool with their fans when the sun set behind the tree, finally bringing shade. This was the time to relax and gossip while sipping tea or munching black sugar coated with toasted ground wheat flour. One evening the subject was my grandfather. One person caused a burst of laughter among the women by imitating the way my grandfather carried himself. My mother did not know how to react and blushed. I wish I could be under the banyan tree once more. Smiling faces of good-natured neighbors, the big banyan tree, the evening ocean, and the red evening sky are treasured memories of my home. I wish I could visit it at least in my dreams.

My paternal grandfather was a ship builder. He also owned junks, and had people working for him. They set sail and brought back white coral to be used as building materials. He was physically handicapped. His back was bent over at a 90-degree angle due to a back injury he suffered when he was young. However, he never complained. He always sat in the living room near the veranda facing the ocean, because from there he could see his boats. When they did not return on time in fair weather he grumbled and became irritated. When the weather was good the boats could bring back coral twice a day. When the weather was bad they could bring it once a day. “Time is money” was his motto, and he was a hard-working man. He was self-employed with an office that was far from luxurious. At home he always had newspapers, an abacus, a brush and ink stone box and white rolled paper in his room. There was a magazine, Women’s Friend among the pile of newspapers. I did not understand why he read Women’s Friend. Later I learned that his wife passed away, leaving him to bring up eight children alone, and he needed help.

My father was the fifth child and when his mother died he was ten or eleven years old. A middle-aged couple lived with them. The wife worked as a maid and the husband as a caretaker. Since grandfather could not walk straight and perhaps was a little embarrassed, whenever he went to a barber shop, public bath, or downtown, the caretaker took him by rickshaw. His home consisted of a big and a small house connected by a covered roof. In between there was a yard and a pond filled with carp. Near the pond was a kumquat tree bearing fruits. At the corner of the yard was a tall banana tree. My mother used banana leaves to wrap rice balls. During summer, we lost our appetites because of the heat and heat rashes. To improve our appetites, my mother would often make rice balls wrapped in banana leaves, put them in a basket, and take us to a breakwater where we enjoyed a picnic lunch while watching pon-pon boats. The ocean breeze cooled us and seemed to cure our rashes.

When bananas were on the tree, I could not wait until they were ripe, and begged my father for them. My father picked the green bananas, wrapped them in newspaper, and put them in a rice barrel. By the time we forgot about the bananas a few days later, they were ready to eat. About ten meters away from the veranda were four or five banyan trees. They were trained to grow sideways and were 20 or 25 five meters long. A banyan tree with a big branch was ideal for hanging a swing set. During summer nights, we could see fishing boats with their flickering lights; the evening breeze blew gently; and stars in the dark sky glowed mysteriously. When my grandfather was about 70 years old, he remarried. The woman he married did not have children. I am sure they were happy to find companionship in their old age. It did not take too long for us grandchildren to become attached to our new grandmother.

My parents were not blessed with children for a long time. I was born after nine years of their marriage. I call my mother Kunibu in Okinwawan (bergamot orange, written in the characters for “nine-year mother,” Kunenbo in Japanese). Afterwards, like a horse that starts running and never stops, she bore three more children, and finally joined other mothers who were busy with child rearing. When I was six years old, our family experienced many tragedies. My younger sister suddenly became ill with encephalitis. The day before she died, my 5-year-old younger brother, Kōshin, drowned at the Tomari Port. My parents were too busy taking care of my sister and did not have time to pay attention to my brother. Guilt tormented them. The house was in turmoil. My mother’s sobs of despair pierced my little heart. When we returned home after entombing my brother, we learned that my sister had passed away. My mother’s refusal to leave our family tomb made others cry with her.

When the anniversaries of their deaths came two days in a row, my mother prayed in front of our family shrine and cried quietly, sitting on the veranda watching the ocean. I felt sorry for her, and when I sat next to her to comfort her, she wiped her tears and smiled at me. The house at that time was gloomy and oppressive. I still remember vividly these tragic events that took place 63 years ago. My younger brother would be 68 years old now. I wonder what kind of grandfather he would be if he were alive. My 3-year-old sister was a strange, mystical child, different from ordinary children. When my mother was going out, my sister would ask her, “Where are you going?” using the honorific expression like a grown-up talking to an elder. Our neighbors commented on her mysterious behavior.

Five years after the tragic incidents, my brother Kōkichi was born. Our family finally was relieved of gloomy obsession, and the house again was filled with laughter. I was eleven and my younger brother, Kōzen, was six. With the youngest boy, Kōkichi, we three grew rapidly and stayed healthy.

When I was in the first grade my father used to comb my hair, and put rouge on my cheeks even though I did not want him to. As soon as I left the house, I rubbed the rouge off my cheeks.

For us the sea was our second home. When summer arrived, we played by the sea with neighborhood children. We taught ourselves to swim. When junks and Yanbaru boats left the port, there were no obstacles, and we could swim to our hearts’ content. Small children swam or splashed water in the shallows. Those who could swim swam between Tomari and Kaneku beaches. I took a wash basin, put small kids in it, and swam. We also floated cucumbers in the salty water, eating them while we swam. The salt water enhanced the taste of the crunchy cucumbers. In those days the unpolluted water was safe. We had no toys, but found ways to entertain ourselves in nature. My mother, who had lost her child in the water, did not want me to play by the sea, and often came to warn me.

Beyond Tomari Port was Kaneku beach and Mitujii. On the other side was Shinyashiki and beyond was Aja. The area was filled with sea water at high tide, but low tide created a vast beach and people came to collect sea shells. I also went to collect shells with my neighbors. Chinbora and Hicharan shells were found under rocks. They were cooked and the meat was added to aburamiso (sautéed bean paste) as a nice addition to my school lunch. Once I was turning over rocks looking for sea shells when an octopus suddenly attached itself to my foot and calf with its suctions. I tried to take it off, but it refused to come loose. I screamed and shook my leg. I took off my shoes and almost fainted with fear. Fortunately an elderly man approached and removed it. I was so frightened that I never again went to collect shells. The man, ignoring my fright, just left my side smiling with his lucky harvest, an octopus.

My mother used to wear traditional Ryukyuan kimono with her hair coiled in a special Ryukyuan knot with a shiny silver hair pin on top. Indigo linen kimono worn loosely in ushinchi style went very well with her hair. My mother looked especially beautiful when she was carrying a parasol. Okinawan kimono does not require heavy sashes as in Japan, and looks very natural and comfortable. The Ryukyuan style of kimono that was adopted during the period of the Ryukyu Kingdom is suited to the climate and very beautiful.

My father was an uminchu (man of the sea) and frequently wore only a loin cloth. I was embarrassed by his attire, and was worried about my friends’ reactions. Whenever he wore nothing but the loin cloth, I wanted him to dive before my friends saw him. The loin cloth was the standard attire among uminchu at that time, but it always irritated me. I hated his loin cloth, but he was a good father. According to my mother, in winter my father always warmed cloth diapers inside his kimono for the next use. My children and my younger brothers’ children also used these diapers as if it was his privilege to warm them for his children and grandchildren. My father was a shipbuilder, and dedicated his life to shipbuilding. He was a talented builder, but I do not think he was a good businessman.

The Lull Before the Storm as War Approaches

Shōwa 15 (1940) was a year before the outbreak of the Pacific War. It was a quiet time on Okinawa with half of the roughly 600,000 citizens making a living fishing and the other half farming.

Assimilation into the mainstream Japanese culture was making inroads into our local culture, but the islanders still adhered to tradition. My mother and our neighbors, for instance, were still wearing Ryukyuan style kimonos and daily conversation was in Okinawan. I spoke standard Japanese at school and Okinawan at home. People in my parents’ generation had names that were distinctive to Okinawa. For example, men’s typical names were Makaree, Taruu, Sanree, Machuu and Kamijuu. Women’s were Chiruu, Ushii, Kamii, Utuu, and Makatee. The schools ran campaigns to “Speak Standard Japanese.” If pupils spoke dialect, they were punished, or had to carry a special placard to show that they had spoken the forbidden tongue. When we slipped into it accidentally, we looked around sheepishly to make sure that the teachers hadn’t heard us. The school was somewhat oppressive in that way. Daily life, on the other hand, was carefree and peaceful. My neighborhood was so quiet that the only sounds we could hear were a carriage’s squeaking wheels and the pleasant echoes of horses’ galloping. Food was rather limited in variety. The main staples were rice, sweet potatoes, fresh fish, vegetables, fresh tofu, and seaweed. Occasionally, when financially possible, fish cakes, meat, and eggs were served. Our eating habits were very simple, but everybody had enough to eat. Men were strong, and women were hard working. Neighbors were thoughtful, warm, generous and forgiving. The island was small, but the islanders’ hearts were many times bigger.

We celebrated the New Year of Shōwa 16 (1941) as usual by decorating the front entrance of our home with bamboo, pine trees, and the rising sun flag. New Year’s greetings were exchanged among neighbors. My mother was busy making special soup, a sauteed seaweed dish, red bean rice, fish tempura and sashimi. The fire god (hi nu kan) in the kitchen was decorated with a piece of charcoal wrapped in seaweed, pine tree branches, and an orange. Children were looking forward to receiving New Year monetary gifts (o-toshidama). We would count the money we collected with great excitement as the day progressed.

Families donned their best clothes to go to the Naminoue Shrine. We crossed Tomari Bridge, went through Suiwataibashi and on to Wakasa-machi which was crowded with people. Whenever we visited the shrine on New Year’s Day, the sea wind blew and piercing cold chilled our bodies. When we finally came to Naminoue Street, the road was already packed with worshippers. There was a group of middle school students in karate uniforms running toward the shrine shouting in unison through the icy cold wind. Summer arrived in the southern island, seeming to skip spring altogether. In June we were surrounded by the shrill chirping of cicadas, which seemed to make mid-summer even hotter. Neighbors came out and gathered under the trees carrying their fans. They brought popo (rolled pancake), sweet potato pudding, and donuts. My mother brought tea. The women enjoyed gossiping. The islanders knew how to cope with long, hot summers.

Gigantic masses of clouds looked like floating cotton balls in the endless blue sky. In the

sweltering heat, children’s foreheads and necks were covered with heat rash. My mother wiped us with towels and sprinkled on talcum powder. Our favorite summer food was watermelon. Since we did not have a refrigerator or air conditioning, we filled an urn with water and kept the watermelon there all day. When cold watermelon slices were served, children took big bites, ignoring the sweet juice that ran down their faces. Arrival of the fall made us forget the mid-summer heat and healed our weariness from it. One day I took a walk toward Sōgenji Temple through a pine forest. I picked flowers which I intended to press for decorations. I got the idea from a middle school girl, Higa Akiko. The area was surrounded by tombs that made me nervous. So I turned back. Pampas flowers were in full bloom and shaking like long-necked dolls. The white blossoms were as smooth as velvet. In the evening of the August moon (August 15), every family celebrated the full moon by offering pampas grass with its flowers and fuchagi (bean-covered rice dumplings). I always wondered about the old belief that on that night a rabbit made rice dumplings on the moon. The autumn passed as usual, and we were unaware that the war was about to pounce on us.

The Pearl Harbor Attack and Early Victories Celebrated

On December 8, Shōwa 16 (1941), we heard the news that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor. At school during morning assembly, our principal announced, “Japan had no choice but to declare war against Britain and the United States because they attacked and damaged a Japanese Red Cross ship.” I felt somewhat nervous, but in the past, Japan’s wars (the Russo-Japanese War and the Manchurian and China Incidents) were fought far away, and the current war apparently had nothing to do with Okinawa, so we were not afraid.

Immediately after the attack, all Japan was immersed in militarism. I, too, was very proud of Japan and admired the brave Japanese soldiers. Japan had never experienced defeat, and we had a feeling of superiority. All day long, news of victories was broadcast over radios where crowds gathered. “We won,” “We won.” People were intoxicated as if at a festival. I was only a child, but was swept up by the victorious mood and high spirits. We heard about the Imperial Declaration of War over the radio. I was only a fifth grader, but sensed that this was a big event for Japan.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, people’s spirits rose steadily, like the rising sun, and the cold north wind from the sea did not bother us, Celebrating the New Year of Shōwa 17 (1942) was most memorable, and the military mood heightened my spirits. I was burning with patriotism, and pledged that I would do my utmost for the nation. Our family visited the Naminoue Shrine as usual. The shrine was more crowded and animated with worshippers than in other years. After praying, we bought Fukusasa (bamboo branches to bring good luck). Along the road to the Shrine were two or three noodle shops. It was our custom to stop for bowls of noodles on our way home from the shrine, but that year we went straight home for my mother’s New Year dishes, ignoring the aroma of chopped green scallions coming from these shops crowded with customers.

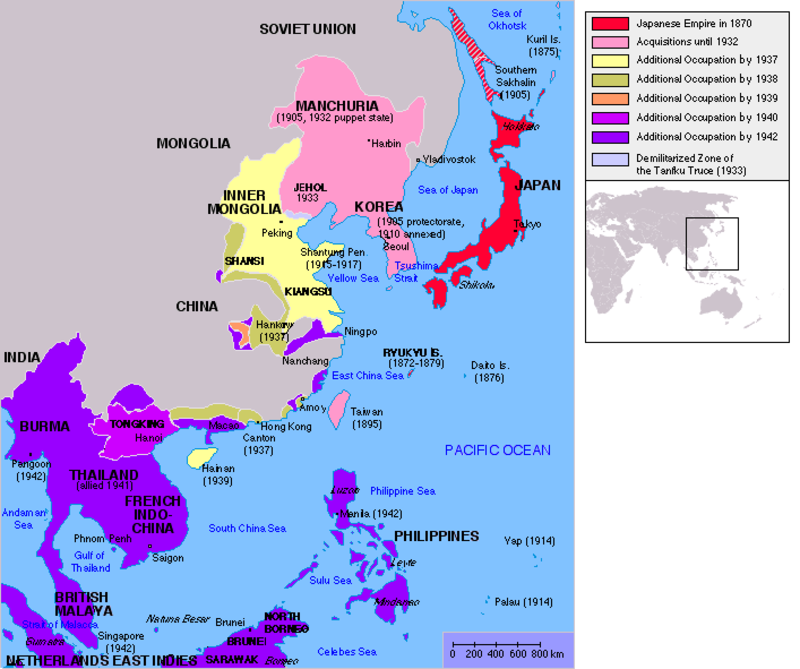

January and February passed quickly, and I entered the 6th grade in April. Around that time, the presence of soldiers in army and navy uniforms became conspicuous, but they were not carrying weapons, and looked relaxed. News of Japanese victories was broadcast in rapid succession. Japan had already invaded the Philippines, Borneo, the Malaysian Peninsula, Celebes, and Singapore. We made a huge map at school, and put little rising sun flags on locations that were occupied by Japan. Befitting a nation training for war, girls learned how to use a shafted axe called a naginata (halbard) at school. We realize now how absurd this practice was. However, we really believed that we could stop the enemy’s shells with a halberd. Never having experienced war, we did not know the real power of weapons, and we practiced very hard.

Music also reflected the war mood. Children’s songs were gradually replaced with songs about soldiers, warships, and fighter planes. When I was small, the songs or stories we learned fostered in us wonderful imaginings and dreams, but adults now used music to lead us to war. Adolescent girls, expected to be “guardians behind the guns,” fell in with the martial spirit by singing military songs in which white lilies, mountain cherry blossoms, and plum blossoms were used allegorically to idealize the war.

“Yamazakura” (Mountain Cherry Blossoms)

Mashiroki Fuji no kedakasa o

Kokorono tsuyoi tate to shite

Mikuni ni tsukusu ominara wa

Kagayaku miyo no yamazakura

Chini saki niou kuni no hana

Mountain Cherry Blossoms

Noble Mt. Fuji covered with white snow

Is the powerful shield for young women’s soul

Who dedicate their lives to their country,

They are mountain cherry blossoms in full bloom,

Their Sovereign’s beautiful flowerers

“Umi yukaba” “When We Go to Sea”

Umi yukaba mizuku kabane

Yama yukaba kusamusu kabana

Okimi no he ni koso shiname

Kaeri wa sezu

Across the sea, corpses soaking in the water,

Across the mountains, corpses heaped upon the grass,

We shall die by the side of our lord.

We shall never look back.1

The Tide of War Turns Bringing an Expanded Draft, Civilian Mobilization, and Food Shortages

Japan’s string of victories was short-lived. The winds of war shifted by the latter half of Shōwa 17 (1942). The massive U.S. offensive brought defeats to territories occupied by Japan. However, the Japanese government made utmost efforts to convince us that “Victory is certain.” The military and the government were most afraid of spies, and coined the slogan, “If you see a stranger, consider him a spy.” Nobody dared criticize the national policy.

Life became harder day by day. Food rationing was implemented in every village. A long line formed early in the morning in front of the neighborhood store where food was distributed. This was where we went to buy candies as children. We received rice, potatoes, cigarettes, candles, sugar (unprocessed black sugar), and cooking oil, but it was impossible to get enough. Worse, we never knew when the next distribution would become available. In order to supplement shortages, people obtained items on the black market or exchanged goods while being careful to avoid arrest by the police. However, they did not feel that they were committing crimes. This was just a way to survive. About this time, my mother’s brother, Soju Nitta, was drafted into the army and shipped to China. My mother and I made care packages for him. After the war he returned home, nothing but skin and bones. We then learned that he had received none of the packages we sent.

I welcomed the last summer vacation of elementary school that year. It would become the last school summer vacation of my life. When it arrived, my friends, now freed from school work, looked radiant and lively. We were together almost everyday. The vacation, however, was not filled entirely with fun activities. We went to Shinyashiki Park by 6:00 a.m. to do exercises broadcast on the radio. We had to get up earlier during summer vacation. Children went to the park rubbing their eyes and grumbling. No child was excused from the “radio exercises” unless sick. But exercise accompanied by radio music in the cool morning air woke us up and refreshed us. Teachers drew circles on attendance cards when we were there or an “x” if we were absent. When school started again we had to give the cards to our teachers. Therefore, we dared not miss morning exercises.

We also had lots of homework: crafts, drawing, and sewing aprons. The worst was the “Summer Vacation Companion Notebook.” Daily homework was assigned for each page. While having fun, we were constantly reminded of the unfinished pages. I tried to complete the missing days’ information at the end of the summer, but each page required that we record that day’s weather conditions. When the summer was almost over I had to “create” the weather for the days I had skipped. I could not ask my parents about the weather, so I borrowed my neighbor’s notebook to copy the conditions for each day. This last vacation brings a smile now. In spite of the hardships, it was an enjoyable time. Those friends I played with are all in their 70s now.

During Shōwa 18 (1943), we felt the war encroaching upon us. Islanders were at a loss whether to go to mainland Japan or to Yanbaru, the northern part of Okinawa Island. It was rumored that the United States had invaded Guadalcanal, that Japanese soldiers had suffered honorable deaths, and that Japanese forces were beginning to retreat. The military tried to suppress news of Japanese defeats. We busied ourselves with preparations to defend the nation. Neighborhood associations” were organized everywhere and air-raid drills were conducted. Middle school students between 14 and 18 were mobilized. Housewives were herded into “Japanese Imperial Women’s Defense Associations.” Under the “National Mobilization Law,” all Okinawans, with the exception of young children and the elderly, were subject to forced labor by

the military and the government. Each neighborhood association was comprised of 10 to 15 households, headed by a honchō (leader). The honchō’s duty was to distribute ration cards and survey the neighborhood in the evenings to make sure that no lights were visible. They were also responsible for relaying messages and for the welfare of the members.

Our honchō was Mrs. Heshiki Tsuru . Sometimes during the night, she yelled, “Sakumoto Tsutsu (my mother’s name), this is the official announcement of an air-raid!!!!” Then she ran to the next house yelling again. It was just a drill, but it sounded very real, and we obeyed her orders. As soon as we heard the “air-raid” announcement, my mother and I changed into monpe (pants made out of kimono), put on anti-air-raid hoods, and ran to the drill location carrying air-raid bags filled with emergency kits. The drills assumed that one of our neighborhood homes had been bombed. Men climbed a ladder to the roof, and people on the ground ran a bucket brigade with water from the water supply tank, finally handing the buckets to men on the roof to extinguish the imaginary fires. The drills took place three to four times a week, day and night.

“Mobilized students” were engaged in the construction of air-raid shelters or artillery emplacements. As a middle school student, I was sent to high ground at nearby Oroku or Ameku:, or, to Urasoe behind Shuri. Girls’ soft hands became as coarse as those of construction workers. When soldiers, who were supervising our work, signaled a break, we went under pine trees and licked small pieces of seaweed and cubed black sugar, listening to cicadas chirping. After a short break we resumed work. Soldiers dug with picks, and put the dirt into small baskets. The first girl in a line handed each basket to the next girl, and then to the next. When lunch time was announced we washed our hands and gathered under the pine trees to open our lunch boxes of rice mixed with sweet potatoes and peas, and sometimes sautéed bitter melon or tofu with vegetables, but rarely meat. If an egg dish was in the lunch box, my eyes glowed big with excitement. If there was no

side dish, I ate rice balls with sautéed bean paste inside. However meager the lunch box contents were, after hard labor, any food was a delicious, welcome feast.

Our Shinyashiki Women’s Defense Association was very active. When young men in our neighborhood were drafted and left their loved ones and homes for mainland Japan, the women got together and performed kachaashii (free form dance) with sanshin accompaniment and drums played by elderly people. My mother was not comfortable performing kachaashii. Once when she was pushed forward to dance, she raised her arms, but was too embarrassed to continue and quit within a minute. My father who had never seen Mother dance stared wide-eyed at her.

Around that time “banzai” (Long live the Emperor) send-off cheers were heard from many directions starting in the early morning. When ships departed, they were sent off with waving rising sun flags and military music. We sent soldiers sennin bari (thousand-stitch belts). They were sewn by women with red thread praying for soldiers’ success and safety at war. I stood on a street corner requesting women passers-by to add a few stitches. The commercial port became a military port. Military ships were seen often, heightening the feeling of approaching war. The masculine white uniforms of sailors were most becoming with matching sailor hats. When young sailors passed by we were excited, but did not have the courage to start a conversation.

After I finished Tomari Elementary School, we did not know whether to stay in Okinawa or go to mainland Japan. My father finally decided to stay, and I enrolled in Shōwa Girls School later than usual. We had classes for the first six months, but soon English was abolished, and eventually classes were replaced by physical labor for the military. This is why I only have sixth-grade school education. One unforgettable memory toward the end of the sixth grade was the time I had a coupon for a pair of sneakers. Our teacher inspected our sneakers, and a child who the teacher thought needed new shoes was given a coupon. My shoes were so torn that my five toes were sticking out and the heels were completely worn. It took a year for me to get the necessary coupon.

One morning I was in a line to get rations for my mother in front of the Iha Store. Familiar faces were all there waiting their turns. Women were wearing monpe and men were in black or khaki shirts and pants with gaiters, and rubber-soled tabi (two-toed sneakers). All of us waited our turns while exchanging pleasantries. When my turn finally came, I received about 20 cups of rice, 13 or 15 sweet potatoes, two or three packs of cigarettes, and several candle sticks. Getting the four kinds of items pleased me immensely, but they were the bi-weekly rations allocated for all five members of my family. And there was no guarantee that we would get another distribution in two weeks. In December of that year, the military began drafting students over the age of twenty. Student soldiers were sent to the front after brief training. Shortages of materials became more severe day by day.

Evacuations to the Mainland Begin as Tensions Rise

Following the New Year of Shōwa 19 (1944), the number of soldiers and civilians working for the military increased, and military vehicle traffic became heavier. I could feel the tense atmosphere. Refugees who were escaping to the north passed our neighborhood constantly day and night: young mothers carrying babies on their backs, parents holding children’s hands and a bundle of their belongings; a skinny elderly couple with their backs bent walked unsteadily carrying what they could hold. They were all heading north.

One day in April, my father got on the Shuri Bus at the Higashi-Machi bus stop after he finished some business in downtown Naha. On the bus a stranger asked him where the Tomari Reservoir was located. My father became suspicious of this man who asked about the reservoir that was a lifeline for the citizens, and concluded that he must be a spy. Also on the bus, there happened to be a teacher, Ms. Arume, from Tomari Elementary School. He asked her to keep an eye on this stranger. My father got off at the next bus stop, Uenokura, and ran into the police station. The police arrested the man at the Wakasa bus stop, the second stop after my father got off. Nobody knew what happened to him, but my father talked about this spy incident with great pride for a long time afterwards, as if it were a great achievement.

My classmates started disappearing one by one, and I spent hours wondering about their whereabouts. They went away without even saying, “Good bye.” Some might have gone to mainland Japan, and others might have remained some place in Okinawa. They were all scattered by the whims of fate.

In May, the government ordered my father to go to Miyako Island to repair ships. He was 46 years old, and most men his age were drafted into a defense corps, or rounded up as civilian workers for the military. This was something everyone expected to happen; however, it was unusual to be sent on temporary duty. Soon after my father left, my mother went out to buy sweet potatoes from a farmer with whom she had become friendly. She was wearing monpe and took a bundle in which she had kimono to exchange for food. This amounted to shopping on the black market, which was prohibited. Police surveillance was strict, but it was necessary to break the law to obtain food. After she left, I steamed sweet potatoes and fried eggs. Sweet potatoes had been given to us by the Uezato family across the street. After the breakfast of potatoes and fried eggs, my younger brother became sick. Then I remembered too late that he had gotten sick once before after eating eggs. I carried him on my back to soothe him, but he was not easily comforted. I decided to give him “wakamoto” stomach medicine. Three of us licked the tablets. Since he liked “wakamoto,” he calmed down and stopped crying.

Early in the afternoon I heard my mother’s voice from the kitchen. I ran to the kitchen to find her standing with a huge belly, soaking wet with perspiration. Anybody would think she was about to have a baby. Shocked by my her appearance, I went to my neighbors begging them to come by my house. About 7 or 8 came to find out what had happened. They first looked puzzled by my mother’s condition. Then my mother untied the obi saying, “I’ll take it off. They’re just too heavy.” As she untied the obi, potatoes rolled down on to the tatami mats. Realizing what she had done, my neighbors burst out laughing. It was the first time we’d laughed in a long time. When my mother left home she was wearing her monpe, but she came home in kimono wearing a kimono coat over it to cover her protruding stomach. Apparently, the police did not suspect a pregnant woman. I always felt that my mother was a gentle person, but was surprised to learn that she also possessed this tough side. After this incident she became very popular among the neighbors.

Later, I left to work on the hill in Oroku where artillery emplacements were being built. The construction had been going on for a week. The tedious job of handing baskets filled with dirt to the next person in a line was physically exhausting. Students were supposed to get to the work site by themselves. Meeting at school and walking there with my classmates was enjoyable, but walking about three miles alone from home in Tomari to the workplace depressed me. I had to cross the wooden Meiji Bridge in which there were many holes. Some were so big that I could see the water through them, and my legs became shaky. When a horse carriage passed, the bridge shook hard. As soon as I crossed the bridge, I breathed a sigh of relief.

Evacuation Ships Sunk by U.S. Navy Torpedoes

On August 19, Shōwa 19 (1944) I had a strange experience. We were close friends with the family living across the street from us. Uezato Tadanobu and Ushi had three sons and two daughters, Kami and Tsuru. The sons were in military service, and the older daughter was already married. About 7:00 PM, Tsuru came to visit us. Her parents had gone out to pick up a kimono that had been ordered for her. Tsuru asked my mother if it was all right for me to stay with her until her parents returned. Tsuru was 18 years old, and she was like my big sister. Ever since learning that she was going to the mainland, I felt lonely. I went to her house. Tsuru put out a futon in her 6-tatami mat room and we talked while lying on the futon. She said, “I hear there are many cute dolls on the mainland. I’ll send you a doll.” We talked and talked. A mosquito net was hung in the room, but I could see things through the net under the light. Adjacent to her room was another 6-tatami-mat room. After a while I became tired and yawned. Then suddenly the wooden door opened and there stood a female figure. I could see through the net that water was dripping from her long hair. I was so scared I thought I would faint, and I screamed. I felt cold, unable to open my eyes, and I kept screaming. Tsuru was frightened by my strange behavior, and ran to get my mother who came quickly and held me tightly. She told me to explain what had happened. During this time, Tsuru’s parents returned home. As I explained to them what I had seen, they listened with grave concern. Tsuru’s mother cleared away the net, and prayed in front of the family’s ancestral shrine. Then they went out to check the pig and sheep pens, and the chicken coop. They looked under the floor and behind the back door, but found no one.

Two days later on August 21, 1944, Tsuru was on board the Tsushima Maru at Naha Port headed for the mainland. She was going to work at a military parachute factory. About 1700 passengers including some 800 school children were being evacuated. On August 22, the ship was sunk by torpedoes near Akuseki Island off Kagoshima Prefecture. Fifteen hundred passengers perished; Tsuru was one of them. This tragedy followed the sinking of the Kōnan Maru the previous year. My father’s sister had gone to Argentina right after her marriage. But just before World War II, her husband decided that their four children should be educated in Japan, and in Shōwa 15 (1940) my aunt returned with the Argentina-born children. Her husband stayed behind to run a big coffee farm. My aunt loved fashionable clothes. She wore a fur coat in winter, high-heeled shoes, and a hat decorated with bird feathers. She looked so different that everyone stared at her. The children were all dressed in cute clothes. The boys’ names were Akira and Masatake, and the girls were Mariko and Tamako. My aunt sought my father’s advice whenever there were problems. She called my father “Yatchi,” brother in Okinawa dialect. My father always took good care of them. My aunt gave us a blanket with tiger designs that kept us warm. She also gave us white sugar cubes with coffee in them. When the cubes were placed in hot water, the coffee was ready.

My aunt seemed to be living comfortably, but when the war started, she became worried and decided to evacuate to the mainland. All five of them boarded the Kōnan Maru at Naha Port with 568 passengers. The ship left on December 19, Shōwa 18 (1943), but around 1:30 a.m. on the 21st it was sunk by torpedoes. About four hundred passengers were rescued by the Kashiwa Maru, but this ship, too, was sunk one hour later, and nearly all passengers aboard perished. The news that the ship was bombed and sank caused frantic confusion among the passengers’ families who were desperate to learn the fate of their loved ones. Along with my aunt and her children, hundreds of school children perished. My father frantically tried to make contact with the authorities, hoping that his sister and her children had somehow survived. After two months passed with no news of them, he looked suddenly aged. According to the Okinawa Prefecture Government, a total of 32 evacuation ships were sunk or damaged. They only know the full details about 13 ships. One of my classmates, Nakasone-san, who lived near us, was a Tsushima Maru survivor. I have been told that of 1700 passengers aboard the Tsushima Maru, only 177 survived. The Toyama Maru was also sunk on the way from mainland Japan to Okinawa, east of Tokunoshima Island. Very few of the roughly 4000 soldiers on board survived. These victims are still at the bottom of the sea. Television always broadcasts the annual memorial services for the atomic bomb victims at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but not for the thousands who died at sea. I wonder if my aunt, her children, and Tsuru-san are resting in peace at the bottom of the ocean. I hope that all those ships will be discovered one day to bring closure to their families.

Sea planes that I had never seen before started to appear on the ocean in front of my house. One young pilot was wearing a flier’s uniform and a hat. His white scarf was flowing in the air and he looked very strong. Many boys and girls were curious about such gallant figures, and felt great admiration for them. Their planes zipped over the water at full speed, and then took off toward the sky.

This reminds me of one sailor, Ken-chan, and his brother. Ships requisitioned by the military were anchoring at Tomari Port. We became friendly with the crew of one ship from Ehime Prefecture and they came to visit us every day. Captain Sakamoto, about thirty years old, and his engineer Ken-chan, about twenty. We were told that Ken-chan was the captain’s brother. The other crew member was about fifty. They would visit us after dinner. Sometimes they brought us a bar of soap, cigarettes, or canned fish. I do not know what happened to them during the war. I hope they survived and are living in Ehime.

In late summer of Shōwa 19 (1944), autumn winds started to blow, bringing cool air in the morning and evening. My favorite pampas grass flowers swayed gently in the breeze, but the heavy reality of the war weighed down on us. Soldiers, civilians working for the military, defense corpsmen, mobilized students, and other civilians believed the military’s propaganda and clenched their teeth, determined to give their utmost. All of us knew what we were expected to do, and did not feel depressed when told that we had to endure until we won the war.

American Firebombs Destroy Naha in 10-10 Air Raid

October 10, Shōwa 19 (1944) was a beautiful day with soft rays of sunshine. I never dreamed that such a bucolic town as Naha would be raided from the air without warning. My brother and I were on our way to school. When we came to Tomari Bridge, about twenty people were gazing toward Naha Port. Among them were several army soldiers. Flying low, three or

four airplanes approached Naha Port and dropped some black objects. With booming explosions, black smoke and flames soared high into the sky. Then gasoline tanks at Naha Port blew up one after another. At first, bystanders thought this was an air-raid exercise, but then they started saying, “It’s unthinkable to practice with real bombs.” Aware of the danger, the soldiers yelled at us, “Everybody, go home!” I ran to our house pulling my brother’s arm.

My mother had already started taking things outside. When she saw us coming, she looked relieved, handed me my two-year-old younger brother who she was carrying on her back, and continued to take furniture and clothing outside. Until then I had never felt so helpless in my father’s absence. With as many belongings as she could carry, my mother led us to higher ground where tombs had been built, a place she thought would be safer. The area was called Enjun, and was the location of a natural cave, Fusu Ferin, that had been designated as an evacuation shelter for the residents of Shinyashiki. We escaped to the cave, but as soon as we were settled inside, my mother went back to the house, telling us not to leave the cave. She returned with clothing and food; then, telling us she had forgotten to bring the family shrine, she went back home again.

Our neighbors were doing their best to bring their belongings. I had been told that at the first sign of an air-raid there would be a warning siren, followed by the air-raid siren, but there were no sirens before the 10-10 air raid, as the October 10, 1944 bombing came to be called.

After bringing our belongings to the cave, we were too afraid to go home. We all squeezed inside and waited. I peeked furtively at the city from behind a tomb. We were told that we could see signs of bombing in the sky. Soon the entire city was in flames. The fires spread uncontrolled, and soon engulfed Shinyashiki. First, Higa’s Barber Shop near the Tomari Bridge went up in flames. After that the fire spread rapidly and the wind blew sparks on to houses along the shore. Once the houses caught fire, they collapsed one by one with a roaring sound. Finally my house started burning. My mother and I watched in tears. All the furniture and other things that had been left inside were lost. Almost all the houses in Shinyashiki burned down. Only a few close to the tomb area escaped the disaster. One of them was my grandfather’s house. Meanwhile, the fires in the city were raging ever more furiously. Residents whose escape route was blocked by fire ran along the shore lines of Naminoue to Wakasa-machi, to Kaneku, to the Tomari Bridge, then to Uenoya and Aja. Long lines of hundreds, maybe thousands, of people were running, but many did not survive. We could not imagine why the Japanese military did not resist. The city of Naha was destroyed easily by just a few enemy planes.

Then, as suddenly as they had arrived, the enemy planes were gone along with the sounds of falling bombs. Later, the sun rose as usual, and people started coming and going among the pampas flowers. After sunset, the sky over the city glowed. When night fell, people came out of the cave and watched their houses burn in silence. I looked at the fire burning in the night. The only sound was insects chirping. Then I heard my mother’s voice. She had brought steamed sweet potatoes and sautéed turnips. I suddenly felt starved. I had not eaten anything all day. Later, my mother told me to get some sleep. I went back inside the cave, but was unable to fall asleep. I could hear adults whispering.

The eastern sky became white and morning dew glistened in the grass, but insects kept chirping at the tomb sites. Cool air filled the area refreshingly as if the bombing raid the night

before had been a bad dream. However, the sunlight revealed white and black smoke rising from my house. Small flames could still be seen from the charred objects in the kitchen where two or three pots lay overturned. I could not bear to look at the pitiful sight of that place I used to call home. All the houses along Tomari Bridge had burned to the ground. I wondered how we were going to survive after this.

Two days after the 10-10 air-raid, I saw a crowd gathered at Kaneku beach across from Tomari Port. I was trying to figure out what had happened when, seized by curiosity, I took off for the beach, though it hurt my feet to run across the coral. When I finally got there, what I saw made me want to cover my eyes. An American fighter plane was down with the pieces scattered all over. Next to it, I saw one thigh and part of a leg. They must have been severed from the rest of the body that was nowhere in sight. The red-burned skin was so swollen it seemed about to burst. I felt sorry for the enemy soldier. But then I remembered that two days before, the American military had killed many people in Okinawa. I felt confused. Twenty or thirty people were standing about. Some looked sad, some wore blank expressions, and others threw stones at the severed limbs.

Then we heard sirens, and everybody hurried away, running across the beach toward the street. There was no place to hide at the beach, and the fear that a bomber might spot us and kill me with a machine gun made me run as fast as I could, ignoring the pain stabbing at the soles of my feet. The bottoms of my sneakers were so worn out that it was like going barefoot. At school I had been given a new pair of sneakers, but I could not bring myself to wear them, and had stored them in my emergency kit bag. I intended to keep wearing the old shoes until they were completely gone.

I did not tell my mother about this incident for a long time. During the next few days, I was obsessed with the ghastly sight of that leg. Later I learned that the tide swept it away. The 10-10 air raid left many people homeless. We were relatively lucky. My grandfather sent his servant to us with an offer that we could live in one of his rental houses that had become vacant because the tenant had emigrated abroad. We moved in right away. My grandparents were living there with a boy three or four years of age I had never seen before. When I asked my grandmother about him, she hesitated for a moment, but then told me the truth. Apparently, before the war started, my father had gone to work on Rasa Island (present-day Okidaitō-jima), where he befriended a woman from the northern Yanbaru area) who gave birth to a boy. It seemed that my mother knew about this. I was not old enough to comprehend the complicated adult world. My mother looked as if there was nothing out of the ordinary about this, and told us his name was Kōsei and that we should call him Sei-chan. “He is your brother, so you have to be nice to him,” she added. We called our mother “Okkaa.” Soon Sei-chan, too, started calling her “Okkaa, Okkaa.” We quickly got used to him, and enjoyed having him around. My father at that time was in Miyako, and knew nothing of what was happening to us. My grandmother told me how Sei-chan came to live with them. According to her, his birth mother planned to marry someone else, and Sei-chan was brought to my grandparents. Strangely, he resembled my grandfather most closely among his grandchildren. So Sei-chan became his favorite grandchild. At least this was how it seemed to me.

Sadly, toward the end of October we had to leave my grandparents’ house. The war situation worsened and we were ordered to move to the countryside. The Uezato family, our neighbors who had also lost their home, found a house in Mekaru Village near Kogane no Mori behind Tomari Elementary School and we moved in with them. The Uezatos had three sons and two daughters. All three sons were in the Army, and the youngest daughter had died aboard the Tsushima Maru. The couple was living with their elder daughter who had a daughter of her own about four years of age. Her husband had a job with the military. With the war situation deteriorating, some of the troops that had been stationed in Okinawa were transferred to Taiwan. Now special volunteer defense corps were organized in many areas of Okinawa. We heard that the U.S. military was bombing Iwo-jima, and had invaded Mindoro Island in the Philippines. We were told that the U. S. mobile units were advancing on Taiwan and the Southwestern Islands. Strangely, however, there were no air attacks, like the 10.10 air raid, during the two months between December, 1944 and February, 1945. When we occasionally heard air-raid warnings, we got ready for the bombs, but they turned out to be just disturbances, the “calm before the storm.”

At the beginning of November my father came home from Miyako Island. He brought back lots of emergency food supplies: pork fat, dried bonito, pickled pork meat, and bean paste. Our house was in a festive mood. Usually we only had rice balls, and occasionally bean paste soup. To celebrate his safe return, Mother cooked rice and beans, radish mixed with seaweed, and pickled pork. She also made saataa andaagii sweet donuts and vegetable tempura. We hadn’t enjoyed such a feast for a very long time and we all ate until we were full. Without even taking a rest, Father started immediately digging an air-raid shelter. He worked from early morning until it got dark with Mother, Mrs Uezato’s daughter, Aunt Kamii, and me. Father gathered up anything that might be useful from the ruins of the fires. And from an anti-aircraft emplacement nearby, he brought back leftover boards. The shelter was finished in about three weeks. Inside the entrance, he built a “living room,” about 4 tatami mats in size (20 by 12 feet). Every morning the sun shone in and warmed it. The shelter was big enough for fourteen people. Besides our immediate family, there were my grandparents, my grandfather’s brother and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Uezato, their daughter Kamii, and her daughter. Six of these people were seventy years of age or older. My father ‘s work reflected the heavy responsibility he felt to the community. Now elderly people did not have to run for the shelter whenever an air-raid warning sounded. They could stay in the shelter every day, and were grateful to my father. Every morning three older ladies sat in the sunny front entrance. They arranged their hair in kampu style and enjoyed sipping tea.

One day I walked toward Tomari Elementary School for no particular reason. I saw many people heading north. There was a man carrying a newspaper among other belongings. I gathered all of my courage and asked, “If you’ve finished reading the newspaper, could you give it to me?” He looked surprised. Then he replied that the newspaper was old but for it was too precious to let go. Then, after pondering a moment, he decided to give it to me. After thanking him I ran to the shelter. My aimless walk had resulted in such a valuable harvest that I sprang up and raced to the shelter. My grandfather’s daily enjoyment was to read a newspaper, but they were not easy to come by, which made him unhappy. I put it in his lap without saying a word As expected, he looked surprised and peered at me over his glasses with his big eyes. He neither smiled nor thanked me. Since I knew him very well, his lack of emotional display did not bother me. I was sure he was pleased. I imagined that he was saying to himself, “Hey, job well done, granddaughter.” Later

I explained to him how I got the newspaper. The next day Grandmother told me how he’d said that, since I had such gumption, I could have gone far in life if only I’d been a boy.

The shelter was surrounded by potato, vegetable, and sugar cane fields. Most farmers had already abandoned their farms and left. Thus, my grandmother and I dug out sweet potatoes, and picked vegetables. Once in a while I felt guilty, but these feelings were replaced by the thought, “It’s unavoidable. We are at war.” At night everything became strangely quiet as if we were not in the midst of war. When I heard insects chirping, I felt peaceful, and could forget my fear of the war. We thought we could stay put in the shelter until it was over. However, within a month, we were ordered to leave for the north. We had worked so hard from morning until sunset to finish the shelter that the mere thought of moving to the far-away north made me feel exhausted. My father hired a horse carriage. Walking more than 40 kilometers (about 25 miles) would have been impossible for four old people over 70 years of age and four small children. We departed for the north with the owner of the horse carriage.

Evacuation to the North

At daybreak on January 6, Shōwa 20 (1945) nine people boarded the carriage–four elders, four small children, and my mother who was to take care of them. The carriage was overloaded with all of us and our belongings. My mother made many rice balls the night before. The children were excited about their first horse carriage trip. Their smiles eased our frayed nerves somewhat. My father, Kamii, and I followed the horse drawn carriage with more belongings on a cart my father pulled. Our job was to help Father pull the cart more than 40 kilometers by pushing from behind. Originally, fourteen people were to go north, but my grandfather’s brother and his wife declined to join us. Their house had survived the 10-10 air raid, and visiting their intact home occasionally gave them great comfort. Another reason they didn’t go with us was that there were abundant food supplies, such as potatoes and vegetables, in the nearby fields the farmers had abandoned. Because our uncle and aunt decided to stay behind, my father planned to return with Kamii and me to Mekaru about twice a month to make sure they were all right, and to take food back with us to the north.

Despite worries about rain that had been falling the past few days, the morning we started our journey it was clear, although the wind from the north made us shiver. If Okinawa had been at peace, we would have sat around the charcoal hibachi roasting special muuchii (rice cake), our favorite pastime in December and February. The war deprived us of these simple pleasures. Nevertheless, I was grateful to the gods that both elderly and young could evacuate to the north in the horse carriage. We passed through the farm road of Mekaru, and entered the prefecture road at Gusukuma where a long line of refugees was heading north to escape the war. Young mothers carried their babies on their backs; small children clasped older family members’ hands; an old man in a tattered kimono walked barefoot with a furoshiki (a large cloth for wrapping and carrying) bundle tied around his waist. We had our own burdens to bear, though, and could not help others. Fortunately, there were no air raid warnings, and we continued our journey. Kamii and I wore monpe suits and air-raid hoods. I knew that in case of an air-raid warning I was expected to hide somewhere. The horse carriage went far ahead of us. At first we tried to keep up, but fell farther and farther behind.

We left Mekaru about 5 o’clock in the morning. After that we rested a few times, quenching our thirst with tea and imbibing some energy by sucking on lumps of black sugar. About one o’clock in the afternoon, my father said, “We’re in Kadena Village, and have gone about halfway. Let’s eat some rice balls.” This was my first trip to the north, and I did not know where we were, but his suggestion made me happy. We stopped the cart and started eating rice balls with fried mustard leaves. I exclaimed, “How delicious.” Kamii said, “When we’re hungry anything tastes good. Even tea is delicious, isn’t it?” Our stomachs full, we felt energized. Now we had to face the second half of the trip. Military trucks were heading north and south. By the time we passed Yomitan, Nakadomari, and Chatan, it was after 8:00, and it was dark when we finally reached our destination, the Toma family’s home in Seragaki Village. Their house was surrounded by fukugi (garcinia) trees. We learned that my mother’s carriage had arrived four hours earlier. She had cooked warm rice and miso soup to welcome us, and then it was bedtime.

The bright morning sun woke me. I still felt tired, but was curious about the new place where we were to stay. I walked outside, and saw five or six houses in idyllic settings among green vegetable fields and rice paddies. I walked along the path through the rice fields. The house where we stayed was situated at the foot of Mount Onna that rose before me. This was a peaceful world, very different from Naha. The owner of the house had welcomed us warmly. “You know we are blood relatives,” he said. I was not used to the northern dialect, but it sounded full of love and kindness. My father was talking with the owner of the horse carriage while he took care of his horse.

Later Father told us he had decided we would leave for Mekaru at 7:00 that evening. At first I dreaded the fifty-mile round-trip journey, but he said, “The horse carriage will pull the cart, and you can ride in it.” This quickly changed my mood, and I even felt a little excited. My father filled a bag with very sweet taro potatoes that the owner of the house had given as a gift for Tanmee and Unmee. He also loaded charcoal while the carriage owner was busy piling on hay for the horse and checking the wheels. I brought a mat to sit on, my air-raid hood, and an emergency kit bag. My mother made rice balls and side dishes for the trip. Also added were a special snack, the pancake like chinpin that was hard to come by during those times. Chinpin is made from flour, baking powder, and black sugar, then is rolled up when done. My mother said the sweets would restore our energy during travel.

We started out at 7 o’clock. Kamii’s daughter, age 4, didn’t mind staying with her grandparents and didn’t cry when we left. Kamii looked relieved. Soon after we left Seragaki village, the East China Sea loomed into view on our right. The beach seemed close enough to touch the sand. We could smell the ocean and hear the gentle sound of the waves. The air was cold, but my padded air-raid hood shielded me from the chill. My father and the carriage owner were busy chatting. Perhaps due to the age difference between Kamii and me, we had little to talk about. So I just listened to the men’s conversations or looked up at the sky. While listening to the sound of waves, I entertained myself with romantic daydreams. On the dark road we occasionally encountered refugees heading north. Some were on foot, some in horse-drawn carriages or wagons. Military trucks headed full speed north and south. Some soldiers flew by on bicycles. They were wearing familiar khaki uniforms and combat caps with arm bands that said “Official,” indicating that they were carrying official messages.

I knew almost nothing of horses before that night. During the trip I discovered many interesting things about them. Horses rhythmically shake their heads back and forth as if to keep their balance. I was fascinated by the movement of their sensitive ears and the sounds coming out of those big nostrils. Their tails wave left and right as if conducting music. These fond memories from my teenage years have stayed with me until today. At the same time I remember feeling sorry for horses that had to work so hard all their lives for human beings. A story that my father told us during the trip back to Mekaru has also stayed with me all these years. According to him, he was drafted and sent to Manchuria to repair buildings and ships. Sometimes he made up excuses to get permission to go out. He told his commander that his tools needed repairs, so he left the barracks with a saw, chisel, and other carpentry tools. After leaving the gate he went wherever he pleased. After spending about two hours outside, he returned. After a while he stopped using the same pretext, fearing his ruse might be discovered. He finished his story by saying, “Item One: a soldier’s duty is to be shrewd.” His phrase parodied the military instructions soldiers were expected to memorize, and we all had a big laugh. Later, we stopped to feed the horse and ourselves. We savored rice balls, stir fried vegetables, delicious tea, and chinpin, as well as good conversation. It was strange that we could still have an enjoyable journey at the same time that terrible ordeals were tormenting others.

The horse carriage brought us back to Mekaru village while it was still dark. The driver dropped us at the entrance to the air-raid shelter. Tanmee and Unmee came outside when they heard the commotion of our arrival. We called my father’s uncle “Tanmee” (grandfather in Okinawan) and his aunt “Unmee.” Unmee looked surprised. “You’re back so soon. I thought Seragaki was far away.” We unpacked our belongings quickly, and Kamii and I went to a little cottage on the farm where we would sleep. My father told us he was going to sleep in the shelter. Kamii and I slept until noon. Unmee brought us a porridge of rice and vegetables that we ate until we were full. She also brought two kimonos from her house and asked me to make monpe suits, one for her and one for myself. My father and Tanmee went to the house to fetch a brazier. We had brought back charcoal from the north, and my father wanted the brazier to heat the shelter. Later in the evening the shelter was comfortably warm, which greatly pleased Tanmee and Unmee who said, “We feel like we’ve been reborn.” They only had one daughter who was five or six years older than my father. He called her “Unmii” (sister). She was blessed with five sons, and had taken four of them to be with her husband in Osaka. The second son was in Okinawa as a student soldier assigned to the signal corps. In their absence, my father was looking after his uncle and aunt in addition to taking care of his parents, the elderly Uezato couple, their daughter Kamii, and he four-year-old daughter, Kazuko. This meant he had to care for six people over the age of 70. We stayed in the shelter for a while. Unmee and Kamii were busy cooking and washing clothes, while I was absorbed in making monpe suits. My father also kept busy, abruptly leaving and returning periodically.

We planned to return to the north with food, but the war situation got worse, and we could not leave as planned. One day a soldier came to tell us that this area had become especially dangerous because a Japanese military anti-aircraft emplacement was only two minutes away on foot. Now we had to find a safer place and, having nowhere else to go, hid inside the same tomb where we had escaped the 10-10 air raid. But this time it was crowded to full capacity. Many people were then taking shelter in tombs. Refugees, constantly on the move, did not have time to dig shelters, which was also a waste of their precious energy for walking. Underground cave shelters were wet, but Okinawan tombs that stood above ground were dry and seemed more welcoming. People also felt safer inside. In order to survive, most of them did not mind sitting next to urns filled with human bones. As many as ten people would stay in one tomb. It seemed that the U.S. military knew about the tombs where civilian refugees hid, and did not bomb them. Still, the tomb that smelled like a mixture of warm tombstones and bones made me sick. I always sat next to the entrance where I could breathe the outside air. I hid rice balls in the grass outside the tomb, and, despite my hunger, waited until an air-raid warning was lifted to go outside and eat them. I just could not bring myself to eat inside the tomb.

Sometimes we saw U.S. planes flying over the tombs toward Naha. When someone reported that they could be seen 5,000 or 10,000 meters high, we looked up. They were not easy to detect. Only when the sun hit a plane could we see its glimmering image. If we blinked our eyes, we would lose sight of it. They looked very small and were hard to find again. Since no anti-aircraft gun could shoot so high, they seemed to cruise arrogantly across the sky.

Once, a small child was crying because he was too scared to go into a tomb. He knew that the dead were inside, and I could certainly empathize. An old woman explained, “Our ancestors love their descendants and are protecting us from danger. You don’t need to be afraid.” After repeated escapes and hiding, our chance to go back to Seragaki where our family was waiting finally came. We planned to carry food back to the others twice a month, but it became harder to find any. Soldiers also started looking for food, and vegetables in the fields disappeared as soon as they were ready to be picked. Three of us planned to go out and look for food one night near the end of January. Tanmee and Unmee decided to stay in tombs during the day and sleep in the shelter at night. After a successful search, we started back at dusk, our cart piled with food. As we passed along the farm road with the cart rattling, noisy insects stopped chirping all at once. The stars were beautiful and sugar cane stalks rustled in the wind. This time the cart was not as heavy as before. My father pulled it in silence. Kamii and I talked and laughed as we walked along. I started singing military songs, and they joined me.

Marching in the Snow

Marching in snow and walking on ice

Where is the river? Where is the road?

How can I abandon a dying horse?

Marching into unknown places

surrounded by enemies.

“Oh, well,” I mutter, puffing on a cigarette

With only two more left in my battlefield bivouac.

I left home with bravado, pledging to bring victory.

How could I die now without distinguished service?

Whenever I hear the sound of a bugle on the march,

The image of waving flags comes to mind.

The song teaches us that soldiers are expected to give their lives, that dying for the country is an honor.

Fateful Parting

After passing through villages, we walked on Tako Mountain. Legend says that it was infested with bandits who stole travelers’ money or belongings. Along the bumpy, winding path, we met a relative, Jirō Maeda, a baker who sold bread and pastries. He told us he was hoarding flour on the mountain, and offered my father some. He gladly accepted three big bags of flour, and loaded them onto the cart. Soon it started raining, and Father covered the cart with a water-proof sheet. As it rained harder, my soaking wet air-raid hood and monpe gave me chills. Now the bumpy path became muddy, and we had a hard time controlling the cart. My old sneakers finally gave out. I had in my air-raid bag a pair of new sneakers that I’d received at school many months before, but I decided to conserve them and walk barefoot. There were no houses on the mountain. We were soaked to the bone, and trembling with chills. My bare feet gave no traction, and I slipped constantly in spite of my exertion. I became so discouraged that I started crying. In order to hide my tears, I looked up at the sky as I walked, clinging to the cart, and ignored the rain falling on my face. To make matters worse, the cart’s handle broke under the weight of the extra flour bags. My father looked for a piece of wood whenever headlight beams from trucks that passed us occasionally lit up the surroundings briefly. Fortunately we found some wood, and he somehow managed to repair the handle with the tools he was carrying.

We finally reached our family. After taking off our wet clothes and eating warm food, we fell asleep quickly. A good night’s sleep restored me to my usual self. Crows were cawing among the fukugi trees that morning when I heard some good news. My classmate Yamazato Yoshiko and her cousin Iha Tomiko were staying in the neighborhood. I was surprised to learn that all of us had relatives in this small village. I also heard that my best friend, Arume Kikuko, was living with her family in the next village. I wanted to see her, but I was not allowed to walk over there. My father told us this time he intended to stay here for three or four days to find a suitable hiding place for us. I was delighted that I could be with my family a little longer, and hoped to remain with them. Many families in the village had shelters on Onna Mountain, including the owner of the house where we were staying, but it was not big enough for all of us. My father told us that he was not planning to dig a shelter on the mountain, apparently remembering that we’d had to abandon our shelter in Mekaru Village. He also said that the mountain was infested with mosquitoes that might give us malaria, and that cooking smoke might attract the enemy’s attention for bombing. After looking around, he found a natural cave facing the ocean near Mehki Point. We were told that in the past lepers lived in the cave, which contained many human skeletons. He gathered the bones in a big basket, buried them in the ground, then piled rocks on the surface as a burial mound for the dead. He arranged them to look like a stone fence in an attempt to avoid scaring the children. Although it had a gloomy history, the cave, its entrance covered with adan bushes, made the best hiding place. From an opening at the top of about 50 centimeters (20 inches) the sun shone in. The sky looked small from the cave, but, thanks to the sunlight, it was never too dark inside during the day. The cave was about 20 minutes on foot from where we were staying, close enough to reach in case of an air-raid warning.

While we were busy setting up the hiding place, we had a surprise visitor, my cousin Sakumoto Koga, grandson of Tanmee and Unmee. He’d been my classmate back in Mekaru and was now a student at a middle school, but currently assigned to the military communications section, and staying on Onna Mountain with his unit. We were like a real brother and a sister. He always handed down his textbooks to me, and when he’d see me playing outside at night, he used to bring me home. He had to return to the mountain as soon he finished the food my mother served. His unit was allowed to stay out for only a limited time.