On September 5, Nishioka Tsutomu, a former professor at Tokyo Christian University, took the stand for the first time at Tokyo District Court. Former Asahi reporter Uemura Takashi had filed a libel lawsuit against Nishioka and Bungei Shunjū in January 2015.

|

Mr. Nishioka leaving court following his September 5th testimony. Photo by Takanami Atsushi |

For the first time, Nishioka admitted to having misquoted from the complaint to the court by former comfort women, as well as an article in a Korean newspaper, both of which Nishioka used as evidence of Uemura’s “fabrication.” He also admitted to adding text not found in the original documents. Nishioka’s claim of Uemura’s “fabrication” in his articles was shaken by the evidence submitted to the court.

|

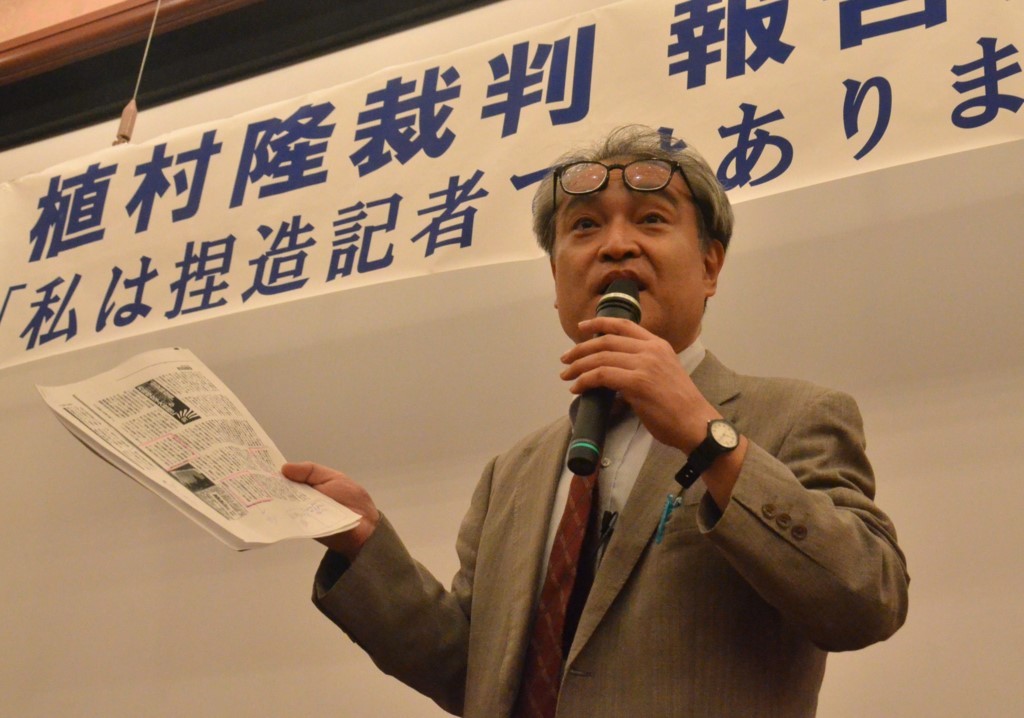

Mr. Uemura talking with supporters at court following his September 5th testimony. Photo by Takanami Atsushi |

In 1991, Uemura published articles in the Asahi Shimbun about Kim Hak-sun, the first Korean survivor of the comfort women system to come forward publicly and tell her story. Nishioka asserted that these articles contained the following “fabrications” by Uemura: 1) The addition of the detail, “I was taken to the battlefield as a member of the ‘girls’ volunteer corps’ (jyoshi teishintai),” a statement Kim herself had never made as part of her personal history; and 2) the omission of a statement that she in fact had made, about how she “was sold by (her) parents into becoming a kisaeng1 (female entertainer) for 40 yen.” As the basis for his argument, Nishioka pointed to a statement by Kim that he claimed had appeared in both an August 1991 article in the South Korean newspaper Hankyoreh and in Kim’s December 1991 complaint against the Japanese government: “I was sold by my stepfather into becoming a comfort woman.”

Commenting in an article that appeared in the February 6, 2014 issue of Shūkan Bunshun, entitled “Asahi Reporter, ‘Fabricator of Comfort Women,’ to Become Professor at Exclusive Women’s College,” Nishioka claimed that even though Uemura knew Kim had acknowledged that “her parents had sold her and [that was how] she became a comfort woman,” Uemura “failed to mention this fact and wrote as if she had been taken by force. It is no exaggeration to say that (Uemura’s) articles were fabricated.” This article triggered an avalanche of nearly 250 emails and numerous phone calls to the women’s university that was scheduled to employ Uemura from April of the same year. Uemura was forced to forfeit his new position.

Additionally, Nishioka stated that Uemura’s mother-in-law was a leading member of a Korean organization that had brought a lawsuit against the Japanese government. He claimed that Uemura “used the pages of the Asahi and had intentionally written lies to advance the cause of the lawsuit.” This led to doxxing, i.e. photos of Uemura and his family as well as addresses being exposed on the Internet. Multiple threats followed, including death threats, and as a result, police security was required for Uemura’s daughter who was a high school student.

Just at the height of these attacks, on October 23, 2014 Shūkan Bunshun published a conversation between Nishioka and journalist Sakurai Yoshiko in which they added further fuel to the “trash Uemura” fire by calling on Uemura to “stop playing the victim.” As a result, Uemura was unable to find full-time employment at any Japanese university; he currently teaches as a visiting professor in South Korea. Recently, he was appointed president of a publisher of Shūkan Kinyōbi (Weekly Friday).

Under cross examination, it became clear that the statement attributed to Kim, which Nishioka claimed appeared in both her complaint and in the article in the Hankyoreh newspaper, existed in neither location. On the contrary, according to Korean newspapers that reported on Kim’s press conference, Kim had clearly stated that she belonged to the “teishintai” (volunteer corps). Moreover, television news footage of the press conference confirmed that she had clearly stated, “I was forcibly taken.”

As for the fact that the statement “Sold by my parents for 40 yen to become a kisaeng” never appeared in Kim’s written complaint, Nishioka acknowledged before the court, “I misremembered.” As to whether he would correct this error, he said, “When this trial is over, I will consider whether that is necessary.”

The Hankyoreh newspaper article was the other piece of evidence that Nishioka relied on. The core of his claim rested on the words, “I was sold for 40 yen, then went through a few years of training to become a kisaeng. Then I went to a place where a Japanese military unit was stationed.” But in court it became clear that no such passage existed in the article.

Even though Nishioka admitted he had made a mistake with his citations, when Uemura’s legal team asked, “Why did you make such additions?” and, “Where did you obtain such statements?” he repeatedly murmured, “I don’t remember,” and “I did not check the original text.” He avoided further clarification.

Nishioka’s translation of the Hankyoreh newspaper article has been repeatedly cited in his principal work, Yoku Wakaru Ianfu Mondai [A Clear Guide to the Comfort Women Issue], as well as in numerous other publications, including in the monthly right-wing magazine, Seiron. In court, Nishioka clearly admitted that as he translated the article, he had inserted sentences supportive of his own theory that Uemura fabricated his comfort women coverage. At this juncture, audible gasps filled the courtroom.

The latter part of the original Hankyoreh article reported Kim Hak-sun as stating that “My stepfather who took me away also seemed to have lost me to the Japanese military by force without ever receiving payment at the time.” Nishioka never quoted this part of the article.

Put simply, Nishioka inserted a sentence of his own while translating the Korean article into Japanese, and he knowingly omitted Kim’s testimony that she was taken by force.

Even after Uemura filed his lawsuit, Nishioka wrote, “(Uemura) failed to write about the important fact that Kim was sold as a kisaeng to a kisaeng house by her mother due to the poverty that Kim herself talked about, and from there was taken to the comfort station by the master of the kisaeng house,” and criticized Uemura’s “fabrication” (“To former Asahi reporter, Uemura Takashi, who filed a lawsuit against me,” Seiron, March 2015).

However, as was revealed in court, Kim never once said that she was “taken to the comfort station by the master of the kisaeng house.” Even in the evidence submitted to the court by Nishioka himself, Kim clearly stated, “My sister and I were taken by different soldiers,” and “My stepfather was threatened by officers with their swords, forced to get down on his knees, and taken away somewhere.”

While ignoring Kim’s testimony that she was “taken away by the Japanese military,” Nishioka added to her story statements that she did not make, such as “I was sold by my parents to a kisaeng house for 40 yen,” and “I was taken to the comfort station by the master of the kisaeng house.” Isn’t this sheer fabrication?

As for Nishioka’s claim that Uemura received assistance from his mother-in-law in writing his articles, it was demonstrated in court that Asahi’s Seoul bureau chief had given Uemura information regarding Kim Hak-sun’s story during a phone call and encouraged him to cover it.

Between Uemura and Nishioka, who was doing the fabricating? The court drama provided a clear answer to this question.

This is a translation and adaptation by the author of Mizuno Takaaki’s post on September 10, 2018 on the blog of Uemura saiban wo sasaeru shimin no kai (Citizens’ Association to Support Uemura Takashi’s Lawsuits).

Related articles

- Asia-Pacific Journal Feature and Hokusei University Support Group, “Japan’s Fundamental Freedoms Imperiled.”

- Norma Field and Tomomi Yamaguchi, “The Impact of ‘Comfort Woman’ Revisionism on the Academy, the Press, and the Individual: Symposium on the U.S. Tour of Uemura Takashi.”

- Katsuya Hirano. “A Reflection on Uemura Takashi’s Talk at UCLA.”

- Eunah Lee, “Reflections on the Symposium at Marquette University: ‘Integrity of Memory: ‘Comfort Women’ in Focus.’”

- Tom Looser, “Talking Points: Brief Thoughts on the Discussion with Uemura Takashi at NYU.”

- David McNeill and Justin McCurry, “Sink the Asahi! The ‘Comfort Woman’ Controversy and the Neo-nationalist Attack!”

- Nogawa Motokazu and Nishino Rumiko, Translation by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen. “The Japanese State’s New Assault on the Victims of Wartime Sexual Slavery.”

- Sven Saaler, “ Nationalism and History in Comporary Japan.”

- Akiko Takenaka, “Japanese Memories of the Asia-Pacific War: Analyzing the Revisionist Turn Post-1995.”

- Uemura Takashi and Tomomi Yamaguchi, “Labeled the Reporter Who “Fabricated” the Comfort Woman Issue: A Rebuttal.”

- Uemura Takashi, “Journalist Who Broke Comfort Woman Story Files 16.5 Million Yen Libel Suit Against Bungei Shunjū: Uemura Takashi’s Speech to the Press.”

- Uemura Takashi, “A Chronicle of My American Journey: The Things I Learned.”

Notes

When Nishioka used the term kisaeng in quoting Kim Hak-sun, he meant “a prostitute.” “Kisaeng owner” would be “brothel owner” according to Nishioka.