Dancing Towards Understanding

On 14 May 2018 the Japanese government’s Council for Ainu Policy Promotion accepted a report sketching the core features of a much-awaited new Ainu law which the Abe government hopes to put in place by 2020.1 The law is the outcome of a long process of debate, protest and legislative change that has taken place as global approaches to indigenous rights have been transformed. In 2007, Japan was among the 144 countries whose vote secured the adoption of the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: a declaration which (amongst other things) confirms the rights of indigenous peoples to the land they traditionally occupied and the resources they traditionally used, and to restitution for past dispossession.2 As a response to this declaration, in 2008 both houses of the Japanese parliament voted unanimously (if rather belatedly) to recognize the Ainu people as an indigenous people, and the government embarked on a ten-year process of deliberation about the future of Ainu policy. The main fruit of those deliberations is the impending new law. But how far will this law go in fulfilling Japan’s commitment to the UN Declaration? Will it, in fact, be a step forward on the path of indigenous people from colonial dispossession towards equality, dignity and ‘the right to development in accordance with their own needs and interests’? Will it take account of the vigorous debates that are occurring within the Ainu community about key aspects of indigenous rights, including the voices of those whose demands are at odds with the aspirations of the Japanese government?3 To answer those questions, it is necessary to look a little more closely at the way in which the pursuit of indigenous rights has played out in Japan over the past three decades or so.

In 1997 Japan finally abolished the assimilationist ‘Former Aborigines Protection Law’ which had governed Ainu affairs for almost a century, and replaced it with a new ‘Ainu Cultural Promotion Law’. The change came after more than ten years of protest by Ainu groups. In 1984, the Utari Association of Hokkaido (since renamed the Ainu Association of Hokkaido) had called for the creation of a New Ainu Law which, if implemented, would have created guaranteed seats for Ainu representatives in Parliament and local assemblies, promoted the transmission of Ainu culture and language, recognized traditional fishing and forest resource use rights, and established an ‘Ainu Independence Fund’ to sustain economic autonomy.4 But, as its title suggests, the law actually introduced in 1997 met only a small part of these demands. It recognized and provided financial support for Ainu traditional culture – including the teaching of Ainu language and the passing on of skills such as woodcarving and textile making – and it led to the creation of a Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture [Ainu Bunka Shinkō Kenkyū Suishin Kikō] which, under the umbrella of the Ministry of Education and the Hokkaido Development Agency, was responsible for encouraging research and promoting activities related to Ainu culture.

Many observers saw this as a first step in the right direction, but were disappointed by the law’s limitations. Ainu activist Tahara Ryoko summed up these mixed feelings when she commented:

We Ainu wanted the restoration of the rights that had been taken away from us, and demanded various things. In the end this turned out just to be a law to promote culture, but all the same it has great meaning as a first step in a new law recognising the Ainu people, and we acknowledge the hard work done by those who created it… [But] we Ainu thought this was a law for the Ainu people. We hoped that when this law was created it would bring great benefits to Ainu. We called for education and culture, the elimination of discrimination, employment measures, an autonomy fund and many things. But the law that has been passed is an Ainu culture law. This is not a law that Ainu alone can make use of. Rather, it benefits wajin [non-Ainu Japanese]. For example, any groups or individuals who conduct research or run cultural events on Ainu can apply for support [under the law]… And if you apply for support, you can get the chance to appreciate traditional dance. In order to be seen and understood, we Ainu will have to dance with all our might.5

Concerns were also raised about the fact that the majority of senior positions in The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture went to non-Ainu: a situation which persisted even as the representation of Ainu in the Foundation gradually improved.6

Ten years on, in the wake of the UN Declaration and the parliamentary recognition of Ainu as an indigenous people, there was a renewed flurry of activity around issues of Ainu rights. In 2008 Hokkaido University conducted a sample survey on the social conditions and attitudes of Hokkaido Ainu, which highlighted ongoing problems of discrimination and disadvantage. The report cited an official figure of 23,782 for the Ainu population of Hokkaido: a figure derived from a government survey which ‘defined Ainu as people who are considered to have Ainu bloodline and those who reside with Ainu people due to marriage, adoption and so forth, and counted those whom municipal governments concerned could identify as Ainu’.7 This figure, though, is recognized to be a serious underestimate of Japan’s total Ainu population. Identification is a complex issue for several reasons. On the one hand, a substantial number of people who are aware of having Ainu ancestry do not acknowledge it in public because of continuing discrimination (and are therefore not identified by municipal governments as being Ainu). Significantly, the Hokkaido University survey (which collected responses only from people who did publicly identify as Ainu) found that 44.1% of respondents reported having felt embarrassed about being Ainu because of experiences of discrimination, while only 2.2% said that non-Ainu friends or acquaintances had made them feel proud to be Ainu.8 On the other hand, the ‘bloodline’ criterion, which identifies people as Ainu only if they are known to have some Ainu ancestry, is problematic because there are people – particularly children of ethnic Japanese heritage who have been adopted by Ainu families – who do not meet this criterion but do identify and are identified by their communities as Ainu. Besides, there are thousands of Ainu people who no longer live in Hokkaido but have migrated to other parts of Japan; and in addition, as we shall see, people with Karafuto (Sakhalin) Ainu or Chishima (Kurile) Ainu ancestry are often neglected in discussions of Ainu issues.

The Hokkaido University survey, which focused on Ainu living in Hokkaido, noted gradual improvements in the social position of Ainu, but also pointed to ongoing disadvantage of the sort experienced by many indigenous communities worldwide. It found that Ainu households had, on average, an annual income of 3.56 million yen: lower than the 4.41 million yen average annual household income for the population of Hokkaido as a whole, which in turn was lower than the annual average household income of 5.67 million yen for the total population of Japan. The survey also found that a disproportionately large percentage of Ainu (27.5%) work in the generally low-wage farming, forestry and fishing sector (compared with a figure of 7.4% for Hokkaido as a whole).9 Although the number of Ainu completing high school had increased, it was still substantially below the national level, and while around 50% of young Japanese people overall attend university, the figure for Hokkaido Ainu as of 2009 was just 21%. Over 50% of Ainu under the age of thirty who responded to the survey stated that they would have liked to attend university, but cited ‘financial difficulties’ as the main reason for being unable to fulfil this ambition.10 The survey discussed the range of social welfare measures which national and local government has developed since the 1970s (including educational scholarships and loans for housing improvements, as well as support for cultural promotion) but noted that the budget for these schemes had been cut back over the past few years. The final question in the survey asked respondents to select five out of twelve suggested measures which they would most like to see incorporated into future Ainu policy. In response, the largest percentage (51%) chose improved educational support for Ainu young people, followed by ‘the creation of a society where human rights are respected and Ainu do not suffer racial discrimination’ (50%), ‘improvement of Ainu employment measures’ (43%) and ‘the teaching of Ainu language and culture in schools’ (33%).11

Meanwhile, an Advisory Council for Future Ainu Policy (including just one Ainu member) had been created under the chairmanship of Kyoto University legal expert Satō Kōji. Its report, issued in 2009, provided a lengthy historical examination of the process by which Ainu people had been deprived of their lands, resources, language and cultural traditions, and emphasized the need to ‘face up to’ this history, without specifically calling for an official apology or compensation. But, although it proposed new measures to improve public understanding of Ainu culture and history and stressed the importance of access to natural resources as an element in protecting and transmitting traditional culture, the report went on to recommend policies which remained firmly focused on the cultural dimensions of Ainu life.

As Uemura Hideaki and Jeffry Gayman have emphasized, the approach to Ainu rights embodied in the 2009 report relied on the argument that Article 13 of the Japanese Constitution already protects the rights of individual citizens, including the right of Ainu individuals, to choose their way of life, so long as this ‘does not interfere with the public welfare’. This protection is presented as providing a basis for a distinctively ‘Japanese approach’ to the issue of indigenous rights. But this conceptual basis of the Japanese government’s approach to Ainu policy is deeply problematic because it is devoid of any explicit recognition of the group rights of indigenous communities: the recognition that is central to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.12 Building on the basis of this ‘Japanese model of indigenous rights’, the core proposal of the 2009 report was the establishment of a ‘Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony’ [Minzoku Kyōsei Shōchō Kūkan], where ‘many people would come together to obtain a broader and deeper understanding and experience of Ainu culture’.13 This Symbolic Space, the report suggested, would ‘be a symbol of the fact that our country, facing the future, will build a society with the vitality of a diverse and rich culture which respects the dignity of indigenous people and is without discrimination’. 14

Designing the Symbolic Space

The report of the Advisory Council provided the starting point for a further eight years of deliberation about Ainu policy, during which the rather abstract concept of a Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony was given concrete form, in every sense of the word. The main deliberations were conducted by a fourteen-member Council for Ainu Policy Promotion [Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi], set up in 2010, and a ten-member Policy Promotion Working Group [Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai], which was created in 2011 and reports to the Council. Both bodies include a number of Ainu participants, but the majority of members on both are non-Ainu, and both have non-Ainu chairs. (The Council for Ainu Policy Promotion is chaired by the government’s Chief Cabinet Secretary, currently Suga Yoshihide, with the Vice Minister of the Cabinet Office as Deputy Chair.)15 In parallel with their deliberations, a number of reports on various aspects of the scheme were produced by Japanese government ministries and assorted sub-committees.

One positive aspect of this process was that it recognized the previously rather neglected presence of Ainu in parts of Japan other than Hokkaido. The president of the Kantō Utari Association is a member of the Council, and a subcommittee of the Council conducted the first small survey of 153 Ainu households outside Hokkaido, covering families as far away as Kyushu and Okinawa. This found types of social disadvantage similar to those found by the Hokkaido University survey, although it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions from its findings, since the total number of Ainu living outside Hokkaido is unknown, which makes it impossible to determine how well the sample surveyed represented the population as a whole.16

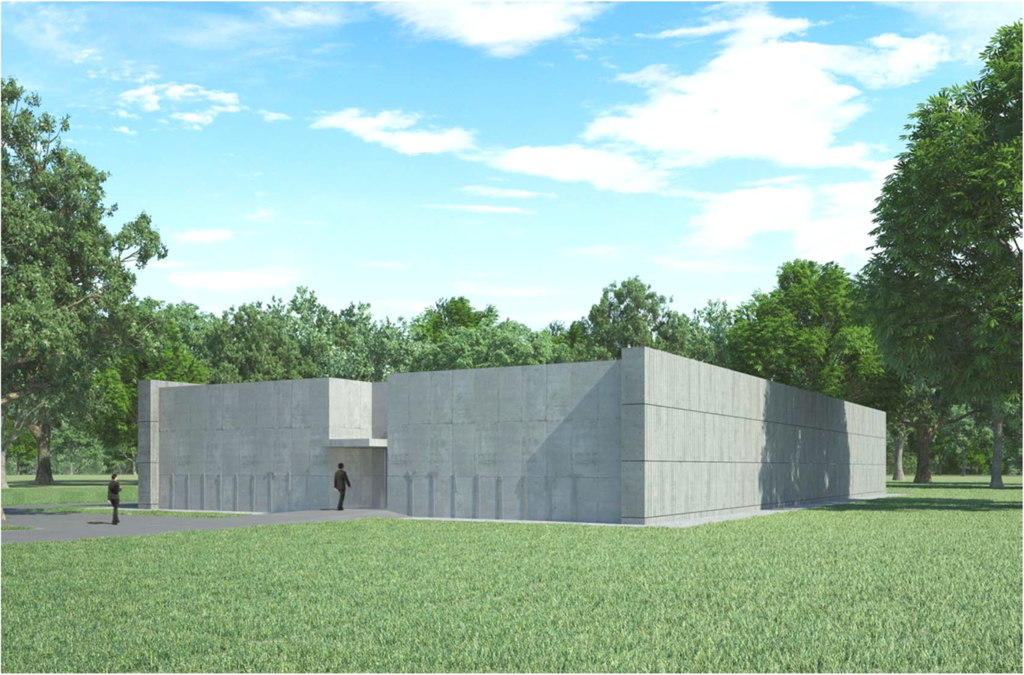

The main negative aspect of the complex deliberation process, on the other hand, was the fact that it failed to create a meaningful way of listening to and incorporating the concerns of the Ainu community at large (a point to which I shall return shortly). Between 2011 and 2012 a Working Group on the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony produced an outline plan for the Space, and this was then further reworked and refined by sub-committees and by government officials, culminating in a revised and more detailed master plan and architectural design which was adopted by the Council in 2016. 17 The Space is to be constructed on the site of the former Ainu Museum at Poroto Kotan, near Shiraoi (which was created in the 1960s and closed in March 2018). It will consist of three elements: a National Ainu Museum [Kokuritsu Ainu Minzoku Hakubutsukan], a National Ethnic Harmony Park [Kokuritsu Minzoku Kyōsei Kōen] and a Resting Place [Irei Shisetsu] for the remains of the dead (discussed further below), and will be opened in April 2020 – in other words, as reports on the project repeatedly stress, just in time for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

|

Design for the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony (Source: Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku Kankei Shiryō’) |

The design, indeed, is rather reminiscent of the dramatic modernist architecture that we have come to associate with the Olympic Games. It will feature four massive concrete structures on the shores of Lake Poroto. The centrepiece will be the ferro-concrete Ainu Museum, towering above the much more modest reconstructed traditional Ainu houses that will cluster at one side of the complex. To its west will be two ‘experience halls’ where visitors can see and participate in traditional Ainu cultural events, and to its east, the stern concrete cube of the Resting Place, accompanied by an obelisk-like monument adorned with Ainu-style motifs. (see Figures 1 and 2) In addition to its official Japanese name, the site will have an Ainu language ‘nickname’ to be chosen through a public competition. Official statements on the project repeatedly stress that the Symbolic Space is expected to attract one million visitors a year. The aims of the Space are described as being to ‘create a focus for promoting widespread national understanding at all levels of Ainu history and culture, and looking to the future, to create a focus which will link to the transmission of Ainu culture and the creation and development of new Ainu culture’.18

The complex is under the control of the Japanese government. The Cultural Bureau of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) is responsible for the Ainu Museum, while the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism (MLIT) has overall responsibility for the park and memorial, and the two ministries share responsibility for cultural training and exchange, publicity and other aspects.19 Day-to-day running of the project has been entrusted to a new Ainu Ethnic Cultural Foundation [Ainu Minzoku Bunka Zaidan], created by merging the old Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture with the management structure of the old Shiraoi Ainu Museum. There will also be a management committee, whose membership is yet to be determined.20 It is worth noting that the old Shiraoi Ainu Museum, which had been created in the 1960s by the local community itself, operated under a more flexible set of rules, while the new National Ainu Museum is firmly under state control and will be subject to higher levels of government scrutiny.21 The public tenders for the construction of major elements of the site were opened in April 2018.22

Perhaps the most striking feature of the convoluted process which produced the design of the Symbolic Space was the large amount of input from government ministries and non-Ainu public cultural institutions in various parts of Japan, and the limited input from Ainu themselves. Of the major reports on aspects of the project produced between 2012 and 2017, three were written by committees set up by the two ministries which will have overall control of the Symbolic Space, and four others were written directly by the ministries themselves. Ainu committee members had some input into the former, but it was the same small circle of five or six Ainu names which repeatedly appeared on the committee membership lists. The three names that recur most frequently belong to senior officials of the Ainu Association of Hokkaido.23 This body, which has existed under changing titles since 1946, is the largest single Ainu organization, and has become the conduit through which key elements of state welfare and scholarship support are distributed to Ainu individuals, but its membership in 2016 was only around 2,300: in other words, some 80–90% of the recognized Ainu population do not have any input into the policies of the Association. It is, therefore, not a representative body for the community as a whole, and there is indeed no overall representative body for the Ainu community. The problem of very restricted consultation, with a handful of non-elected people being treated as though they were representatives of the entire Ainu community, is not a new phenomenon. It dates back at least to the 1997 establishment of the Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture, of which one researcher observes:

The Ministry [of Education] failed to appoint Ainu in a fair and representative fashion. Local tensions were ignited when decision making appeared to rest in the hands of Hokkaido elites, many of whom did double duty as directors in the [Ainu Association of Hokkaido].24

It was only after the 2016 detailed master plan was put in place – and seven years after the start of its deliberations on the overall shape of future Ainu policy – that the Council for Ainu Policy Promotion’s working party undertook consultation with members of the wider Ainu community. The consultations began in December 2017, lasted for three months, and involved closed-door discussion sessions attended by 286 Ainu people in various parts of Hokkaido. Despite this small-scale and attenuated process, the consultations seem to have stimulated lively debate and generated a range of interesting suggestions for the future of Ainu policy. The main proposals put forward by participants included a call for the status of Ainu as indigenous people to be enshrined in law; a demand for Ainu to be given rights of access to state owned land; proposals for traditional fishing rights to be restored, spaces for traditional life practices to be created in all parts of Hokkaido, and support to be provided for autonomous economic and social activities; and a call for Ainu human remains removed by anthropologists, archaeologists and others to be returned. There were also pleas for the teaching of Ainu language and culture in schools; for stronger measures to promote the education of Ainu children and young people; for improved financial support to Ainu farming, fishing and forestry activities; for enhanced welfare for elderly Ainu; and for future discussions about Ainu policy to pay proper attention to questions of gender and regional balance. Some participants in the consultation sessions called for an official apology from the Japanese government for the long history of Ainu dispossession and the destruction of Ainu society and culture.25

The Council for Ainu Policy Promotion’s working party report, which was adopted by the Council two months after the end of the consultation process, fails even to discuss the great majority of these suggestions. The first two-thirds of the report provide further detail about the plans for the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony, while the remaining three pages deal with the likely outlines of a new Ainu law as a whole. The report notes that the consultation process highlighted the diversity of opinions in the Ainu community. It then announces that in future the focus of Ainu policy will be expanded from ‘aspects of welfare’ to ‘a wide initiative embracing regional development, industrial development and international exchange’.26 Given the overwhelming focus of the report’s content on the Symbolic Space, it is clear from the context that, if ‘industrial development’ has any meaning, it refers primarily to the tourism industry. The report goes on to state that the proposals from the consultation process should be considered together with the proposal for the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony initiative, and that an Ainu Law should be enacted as soon as possible to ‘put into effect those policies which are most effective and have the highest possibility of being realised’.27

The unmistakable implication here is that calls for things like an official apology, access rights to state land, restoration of fishing rights, an Ainu autonomy fund, or even expanded welfare for the elderly are viewed by the Council as having a low ‘possibility of being realized’, and have been excluded from the agenda, while the Symbolic Space of Harmony and a handful of related cultural tourism activities have been selected as ‘effective’ and ‘realistic’. There is, indeed an interesting oxymoron in the report’s formulation. Since it is the government who ultimately decides which proposals are to be realized, the ‘highest possibility of realization’ criterion gives the state almost endless scope to decide what to include or exclude. The report ends with a few further proposals, including a plan to display Ainu cultural symbols at Chitose Airport ‘in collaboration with private industry in the lead up to the opening of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony’. There is also a promise to develop a promotional Ainu culture tourist video associated with the opening of the Space, and to examine the inclusion of new material on Ainu in school textbooks.28 But the nature of the material on Ainu history and society to be included in future textbooks remains unclear. One of Japan’s eight approved textbook publishers has recently expanded its coverage of traditional Ainu culture within the junior high school ethics curriculum, but elsewhere there has been little change so far.29

The release of the Council on Ainu Policy’s 2018 report was welcomed by some senior Ainu figures particularly by those in areas which have substantial Ainu tourism sectors. Other responses, though, were more pessimistic. For example, Sasamura Ritsuko, who heads an Ainu cultural study group in Obihiro, observes, ‘I really hope that they mobilize Ainu culture more in local development schemes’, but goes on to note that the new law will not incorporate welfare measures for the elderly because of a perception that it would be ‘difficult to obtain public understanding’ for such measures. She then comments: ‘I just wish they would face up to the history in which [Ainu people] were pushed into poverty by discrimination’.30 Other criticisms were harsher. The Citizens’ Council to Examine Ainu Policy [Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi], a civil society group which contains both Ainu and non-Ainu members, presented Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga with a statement protesting the way in which the government was pushing ahead with the new law: ‘this government-centred process does not approach Ainu as a people who should have an inherent right to self-determination. Rather, it is a colonialist process which only listens to opinion from one side of the debates, and it is no exaggeration to describe it as trampling underfoot the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People’.31 The Citizens’ Council, meanwhile, had put together its own interim report – Let us Realise an Indigenous Peoples Policy that Meets International Standards [Seikai Hyōjun no Senjū Minzoku Seisaku o Jitsugen Shiyou! – containing a range of alternative policy proposals (discussed further in the following section).

Haunting the Symbolic Space

There is little dispute about the importance of giving the Japanese public and international visitors to Japan a deeper understanding of Ainu history and culture. The Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony could contribute to that understanding, as well as creating employment opportunities for Ainu people and opportunities to pass on traditional cultural knowledge to the next generation. It is not surprising, then, that the initiative has been welcomed by some observers, both Ainu and non-Ainu. But the criticism expressed by other members of the Ainu community reflects frustration at the lack of widespread consultation, and deep concern that a process which began as a search for a new policy on indigenous rights appears to have morphed into a state controlled cultural tourism scheme.

The very name ‘Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony’ begs large questions. Is the ‘ethnic harmony’ that the Space symbolizes a noble aspiration or a comforting illusion? In other words, will the displays of Ainu culture and history within the Space not only celebrate the beauty and richness of Ainu tradition, but also face up to painful legacies of colonization, dispossession and discrimination, thereby inaugurating a serious commitment to overcoming those legacies in order to achieve future ethnic harmony? Or will the Space present a ‘cosmetic multicultural’ image, conveying to viewers the message that ethnic harmony has been achieved, or perhaps even that it has existed from time immemorial? Given the diverse range of ethnic groups in Japan, the title of the Space also begs so far unanswered questions about the ways in which the relationship between Ainu and groups like Okinawans, Zainichi Koreans and other minorities will be presented. Will the museum, for example, touch on the story of the help that some Ainu communities gave during the Asia-Pacific War to Korean forced labourers who had escaped from labour sites in Hokkaido?32

The brief descriptions of the future exhibits suggest that the National Ainu Museum will not present a single static ‘Ainu culture’, but will try to link past to present. The plan for the Museum envisages six main exhibition spaces, equipped with the latest augmented reality technology and labelled ‘Our Language’, ‘Our World’, ‘Our Life’, ‘Our History’, ‘Our Work’ and ‘Our Interaction’. Of these, ‘Our History’, will present visitors with a story that extends from ‘the Old Stone Age to the present day’, while in ‘Our Work’ will show how ‘traditional culture, even though it changes, is passed down to the present’.33 It seems clear that the museum will highlight the ways in which traditional Ainu culture is being refashioned in new media through creative works like hybrid Ainu rock music or the highly popular manga series Golden Kamuy, which (although written by a non-Ainu author) introduces readers to important elements of traditional Ainu life.

But deeper public understanding of and respect for Ainu people also requires an understanding that proud Ainu identity may exist in the minds and hearts of people even when they are not performing in visibly ‘indigenous’ or ‘cultural’ ways. And that type of understanding can only be achieved when the discrimination and disadvantages faced by Ainu in everyday life are tackled, so that non-Ainu Japanese, as a matter of course, can have an opportunity to encounter people who proudly identify as Ainu while working in offices, teaching in schools or universities, treating patients in hospitals, presenting the news on TV, serving on local and national government assemblies, working in factories, and so on. Depending how the Symbolic Space is developed, it could become one small step in the long journey to this second form of understanding. But the plan as it stands risks, on the contrary, reinforcing a narrow form of recognition that perceives Ainu identity only in the performance of traditional or neo-traditional culture in spaces of spectacle and entertainment set aside from the world of everyday life.

Important questions about the representation of Ainu history remain to be addressed, both in relation to the displays within the Symbolic Space and to the proposed revision of textbooks. Will the history displayed in the Symbolic Space of Ethnic Harmony, and included in textbooks, remind visitors of the removal of Hokkaido Ainu villages to less fertile and accessible locations, and the banning of their hunting and fishing livelihoods, to make way for the coming of Japanese colonists? Will it confront issues like the stories of the Sakhalin Ainu (also known as Enchiw) who were shifted to Japan in 1875 when Japan transferred control of their homeland to Russia, and were then forcibly removed to Tsuishikari, on the outskirts of Sapporo, where many soon died from epidemics of smallpox, measles, cholera and other diseases whose impact was aggravated by the effects of life in a crowded and unfamiliar environment?34 (So far, the deliberations of the Council have in fact said nothing at all about the Ainu of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, most of whom moved to Hokkaido when their land was again lost to Russia at the end of the Asia Pacific War.) Will it tell the story of the Ainu recruited in the 19th and early 20th century to be sent for ‘display’ in international expositions at home and overseas?35 And how will the history told in the new National Ainu Museum relate to the Resting Place next door, destined to house the ‘repatriated’ bones of Ainu whose remains, in the nineteenth and early to mid-twentieth centuries, were torn from their resting places by researchers and collectors and taken away to universities and museums around Japan and beyond?36 According to government estimates, the remains of at least 1600 individuals are still held by Japanese universities37, with many more in institutions overseas.

This Resting Place has evoked particular controversy amongst the Ainu community. Throughout the period when the new Ainu policy was being formulated, a group of Ainu from Urakawa and other small Hokkaido towns were fighting for the return of ancestral remains which were taken without permission from their community graveyards, some of them within living memory, by researchers from Hokkaido University and other academic institutions. In March 2016, after taking the issue to court, some members of the group finally reached a settlement with the university, and succeeded in returning the remains of twelve people to Kineusu, near Urakawa, for reburial. This helped to open the way for the repatriation of other remains to communities in Urahoro, Monbetsu and Kineusu in 2017. Further struggles for the return of remains to the Urakawa area are currently being played out in the Japanese courts. For members of the small Kotan Association [Kotan no Kai], which has been playing a central role in these struggles, repatriation of remains means the return of the bones of the dead to the earth, as near as possible to the place from which they were taken, in accordance with Ainu tradition. Even though there can be no perfectly ‘traditional’ ceremony to accompany this return, the Kotan Association has tried as far as possible to treat the dead with the respect given to them in Ainu custom. For them, the idea that Ainu remains are to be ‘repatriated’ to a concrete mausoleum in a major tourism complex under the control of the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism is anathema, and is indeed not repatriation at all, but merely the shifting of the dead from one alien space to another.38 Karafuto Ainu descendants are also concerned about the prospects for the return of the remains of their ancestors, and in June 2018 created a new ‘Association of Descendants of Deceased Enchiw’ [Enchiu Izokukai] to confront the issue.39

|

Design for the Memorial Building to House Ainu Human Remains ‘Repatriated’ from Public Institutions at Home and Abroad (Source: Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku Kankei Shiryō’) |

The May 2018 report of the Council for Ainu Policy Promotion working party calls on museums and universities to release information about Ainu remains in their collections as soon as possible, so that relatives or community groups can claim those remains, but states that remains which have not been claimed within six months, or those which cannot immediately be returned to their communities, should be interred in the new Resting Place within the Symbolic Space. But international experience suggests that this time frame is completely unrealistic. Prolonged struggles over the repatriation of indigenous remains in other countries have led to growing acceptance of the notion that remains should be returned to the cultural groups to which they are most closely affiliated, and that a single national resting place is appropriate only where the origins of remains are unknown.40 Such repatriation is an extremely complex process, fraught with pain and conflicting emotions. This process cannot be constrained by bureaucratic deadlines because the tasks of identifying descendants and traditional owners and establishing respectful ceremonies of return are challenging, and because (to cite Hawaiian repatriation campaigner Edward Halealoha Ayau and Cherokee activist Honor Keeler) ‘there is no established period of time by which human skeletal remains lose their humanity and become property’.41 In this context the Kotan Association, whose president – Shimizu Yūji – is also a board member of the Citizens’ Council to Examine Ainu Policy, calls for an apology from museums and universities which participated in the removal of Ainu remains from gravesites, and for a policy focused on returning remains to their original locality with ceremonies that as far as possible follow Ainu tradition.42

Particular unease is evoked by another suggestion in the Council for Ainu Policy Promotion’s 2018 report: that academic researchers, provided they undertake a yet-undefined consultation process, may still be able to gain access to the human remains enshrined in the Symbolic Space memorial for their personal research projects.43 The issue of identifying descendants and traditional owners is crucial here, as it is in the case of the return of indigenous remains. Many international bodies and national governments now have clear rules on the community consultations which must precede and accompany the academic study of the bodies of indigenous people, living or dead. For example, both a 1996 report by UNESCO’s International Bioethics Committee and a document issued by the UN Commission on Human Rights in 1998 emphasize that, in human genome research on indigenous populations, approval from national governments must be ‘complemented by consent from the individuals/local groups selected for the study, whether the consent is obtained directly or through formal/informal leadership, group representatives or trusted intermediaries. Consent would need to be obtained from the most appropriate persons, taking into account the group’s social structure, values, laws, goals and aspirations’.44 Consent, in this context, is not a one-off formality, but an ongoing process. In the words of the code of ethics adopted by the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in 2003: ‘it is understood that the informed consent process is dynamic and continuous; the process should be initiated in the project design and continue through implementation by way of dialogue and negotiation with those studied.45

In Japan, the Anthropological Society of Nippon, the Ainu Association of Hokkaido, the Japan Archaeological Association and the Ministry of Education are currently cooperating in an exploration of ways to conduct research on indigenous remains and burial goods. One outcome of this exploration has been published in the official journal of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, in the form of a paper by Japanese scholars outlining the results of DNA tests on the skeletal remains of 115 Ainu people. The remains are held in Sapporo Medical University and Date City Institute of Funkawan Culture, and the researchers gained the one-off consent of the Ainu Association of Hokkaido at the start of their research project more than a decade ago. Although the provenance of all the remains is known, the anthropologists involved did not at any point consult the local Ainu communities from which the skeletons originated. Some of those indigenous community members were deeply shocked to read about the outcomes of the research, and raised their concerns in public in February 2017.46 The following month, without addressing these concerns, the researchers’ submitted their article to the American Journal of Physical Anthropology for publication, complete with assurances about ethics and consent, and the article was duly published in January 2018.47 An open letter protesting the research methods was sent by Ainu community members and their supporters to the researchers’ academic institutions in May 2018 but has, as of October 2018, failed to receive a satisfactory response.48 If this is indicative of the ‘ways of studying Ainu skeletal remains and burial goods’ to be pursued under the New Ainu Law, there are surely good reasons for concern.

In addition to protesting vigorously about the use of Ainu remains for DNA research without local community consent, the Citizens’ Council to Examine Ainu Policy has put forward a range of proposals for new policies to restore Ainu resource rights, provide compensation for misappropriated assets, and recognize the history and rights of Karafuto Enchiw and Chishima Ainu, and for a law to recognize Ainu as an official language (to be used in registration documents etc. alongside Japanese) in Hokkaido.49 For example, Council member Hatakeyama Satoshi, who also heads the Mombetsu Ainu Association [Mombetsu Ainu Kyōkai] highlights the irony of the fact that the Japanese government insists, in the teeth of strong international criticism, on asserting Japan’s right to continue ‘scientific whaling’, while denying the right of Ainu to maintain the indigenous whaling traditions which are permissible under international law.50 Tazawa Mamoru, who is both a board member of the Citizens’ Council and Chair of the Karafuto Ainu Association [Karafuto Ainu Kyōkai] points out that, because of the complex history of multiple displacements of Karafuto Ainu, it is extremely difficult for Enchiw/ Karafuto Ainu even to document their own origins, which means that they are almost entirely excluded from enumerations of the Ainu population. Tazawa emphasizes that Karafuto Enchiw/Karafuto Ainu have as much right to recognition under the terms of the UN Declaration as any other indigenous group, and calls on the Japanese government to provide that recognition.51 The Citizens’ Council also raises the long neglected issue of Ainu fishing cooperatives whose assets were placed under state control as part of Meiji assimilationist policy, and calls for the return of those assets.52 Yet there is no evidence to date that the Japanese government is paying any attention to these dissenting voices. This raises crucial questions about ‘representation’ in both senses of the word: which groups and opinions are being represented in the planning of the Symbolic Space, and how will Ainu history and society themselves be represented in the Space? These issues deserve particular attention because of extensive influence which (as we have seen) the government will wield over the operations of the new National Ainu Museum and the Symbolic Space as a whole.

Beyond the Space

The title of this article, ‘Performing Ethnic Harmony’, is not intended to be wholly negative or cynical. Performance matters. When bodies perform, hearts and minds may sometimes follow. Children who grow up visiting a site where they learn about and experience the wealth and variety of Ainu culture may gain new perspectives on the cultural and ethnic diversity that has always existed in the space we call ‘Japan’. But indigenous tourism is a two-edged sword. In the words of the 2012 Larrakia Declaration on the Development of Indigenous Tourism, ‘while tourism provides the strongest driver to restore, protect and promote indigenous cultures, it has the potential to diminish and destroy those cultures when improperly used’. It was to avoid the potentially destructive dimensions of tourism that the Declaration went on to insist on the importance of indigenous autonomy and control in relation to tourism projects centred on their culture: ‘indigenous peoples will determine the extent and nature and organizational arrangements for their participation in tourism and … governments and multilateral agencies will support the empowerment of indigenous people.’53

There is another risk, too, associated with large-scale symbolic construction projects carried out in the name of ethnic harmony. As some critics of the project point out, when the government spends large sums of money on ‘Ainu projects’ whose tangible benefits reach only a small section of the Ainu community, this creates a double bind for those who do not reap the direct benefits of this spending. They are left with little support to overcome the struggles they face in everyday life, while the general public is left with the impression that large sums of taxpayers’ money are going to support Ainu ‘special privileges’ [tokken]: an impression which all too easily fuels right-wing backlashes against minority rights. In this context, it is worth remembering that, despite a number racist campaigns attacking Ainu rights in recent years, an Anti-Hate Speech law enacted in Japan in 2016 limited its scope to foreign migrants in Japan, and provided no protection for indigenous minorities such as the Ainu.54 The government’s published statements on the future of Ainu policy also include no plans to extend the law to cover Japan’s indigenous people.

The social impact of the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony, then, will depend, not simply on the exhibitions and performances that take place within the Space, but, much more importantly, on what happens to indigenous rights, culture and identity outside the Space, and how inside and outside are connected. State supported cultural tourism and monument building projects can achieve positive results. But they do not restore lost land or resource rights, provide redress for dispossession, create opportunities for indigenous voices to be heard on the political stage, or support the education and welfare of indigenous people who are not directly involved in the project itself. Only conscious efforts to assure that cultural tourism is linked to redress and the creation of new opportunities for indigenous people can achieve such positive results.

In other words, the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony (together with the cultural events that occur on its fringe) does not constitute an indigenous rights policy, and cannot be treated as a substitute for one. If there is one lesson that has been learnt from the pursuit of indigenous rights around the world over the past three decades or so, it is that the righting of centuries of dispossession is a long and arduous process that requires commitment, sincerity and persistence on the part of both state and society. Even after steps have been taken to put land or resource rights laws in place, apologies have been made and funds have been allocated to promote autonomy or tackle inequalities, the results of those steps take decades if not generations to be fully felt, and constant effort is needed to prevent reversals caused by political backlash or simple inertia. There are no viable short-cuts; there are no quick fixes.

If the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony is really intended as a starting point of a long journey of dialogue and policy-making to overcome injustice and secure recognition, rights and redress, then it could be a small step in the right direction. But if it is used to restrict the right of Ainu communities to demand the return of their dead, while privileging the rights of non-Ainu researchers to use the dead as research material, then it will become a symbol of the enduring legacies of colonial science. And if it is seen, and presented to the world, as an endpoint – the culmination of the search for a new Ainu law, and a triumphal declaration to Japan and the world that Japan’s indigenous issues have been solved and ethnic harmony prevails – the Space and the surrounding Olympic year performances will be a giant leap backwards for indigenous rights.

I would like to thank Jeff Gayman and ann-elise lewallen for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Related articles

- Uemura Hideaki and Jeffry Gayman, Rethinking Japan’s Constitution from the Perspective of the Ainu and Ryūkyū Peoples

- Ann-elise lewallen, Ainu Women and Indigenous Modernity in Colonial Japan

- Komori Yoichi, Helen J.S. Lee and Michelle Mason, Rule in the Name of Protection: The Japanese State, the Ainu and the Vocabulary of Colonialism

- Simon Cotterill, Ainu Success: the political and Cultural Achievements of Japan’s Indigenous Minority

- Mark Winchester, On the Dawn of a New National Ainu Policy: The “‘Ainu’ as a Situation” Today.

- Yukie Chiri and Kyoko Selden, The Song the Owl God Himself Sang. “Silver Droplets Fall Fall All Around,” an Ainu Tale

- Katsuya HIRANO, The Politics of Colonial Translation: On the Narrative of the Ainu as a “Vanishing Ethnicity”

- ann-elise lewallen, Indigenous at last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir

- Chisato “Kitty” O. Dubreuil, The Ainu and Their Culture: A Critical Twenty-First Century Assessment

- David McNeill, Oda Makoto, Pak Kyongnam, Tanaka Hiroshi, William Wetherall & Honda Katsuichi, The Diene Report on Discrimination and Racism in Japan

- Joshua Hotaka Roth, Political and Cultural Perspectives on Japan’s Insider Minorities

Notes

Asahi Shinbun, 15 May 2018; Hokkaidō Shinbun, 15 May 2018; Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku’, 14 May 2018, (accessed 27 May 2018).

United Nations, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Geneva, United Nations, 2008, (accessed 28 May 2018).

See Richard Siddle, Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan, London and New York, Routledge, 1996, p. 184.

Tahara Ryoko, ‘Genba kara Mita Ainu Shinpō no Mondaiten’, in Kayano Shigeru et al, Ainu Bunka o Keishō suru: Kayano Shigeru Ainu Bunka Kōza II, Tokyo, Sōfūkan, 1998, pp. 162–166, quotation from pp. 163–164.

As of 2010, 10 of the 17 members of the Foundation’s Board of Directors and 8 of the 18 members of its Board of Councillors were Ainu; see Ann-Elise Lewallen, The Fabric of Indigeneity: Ainu Identity, Gender, and Settler Colonialism in Japan, Albuquerque NM, University of New Mexico Press, 2016, p. 77.

Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, University of Hokkaido, Living Conditions and Consciousness of Present-Day Ainu, Sapporo, University of Hokkaido, 2010, p. 3 (accessed 26 May 2018).

Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, Living Conditions and Consciousness of Present-Day Ainu, p. 153.

Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, Living Conditions and Consciousness of Present-Day Ainu, pp. 33–35.

Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, University of Hokkaido, Living Conditions and Consciousness of Present-Day Ainu, pp. 68–71.

Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, Living Conditions and Consciousness of Present-Day Ainu, p. 170.

See Uemura Hideaki and Jeffry Gayman, ‘Rethinking Japan’s Constitution from the Perspective of the Ainu and Ryūkyū Peoples’, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol. 16, issue 5, no. 5, 1 March 2018 (accessed 30 March 2018).

Advisory Council for Future Ainu Policy, ‘Final Report’, p. 27 (I have adjusted the English translation on the basis of the Japanese original).

For the membership of the committees, see ‘Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Meibo’, and ‘Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai ni Tsuite’, (both accessed 28 May 2018).

Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi, ‘“Hokkaidō-gai Ainu no Seikatsu Jittai Chōsa” Sagyō Bukai Hōkokusho’, June 2011. (accessed 28 May 2018).

Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi, ‘“Minzoku Kyōsei no Shōchō to naru Kūkan” Sagyō Bukai Hōkokusho’, June 2011, (accessed 27 May 2018).

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku Kankei Shiryō’, (accessed 28 May 2018), p. 2.

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku’, p. 2.

The old Shiraoi Ainu Museum was a ‘general incorporated foundation’ [ippan zaidan hōjin], while the new museum will be a more highly regulated ‘public interest incorporated foundation’ [kōeki zaidan hōjin].

For further details of these reports and of committee memberships, see Website of the Council for Ainu Policy Promotion.

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku Kankei Shiryō’, p. 34.

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku’, p 9.

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku’, p. 9.

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku’, pp. 10–11.

Hokkaidō Shinbun, 28 March 2018. The publisher in question is Kyōiku Shuppan, whose year three junior high school ethics texts now include four pages of material about the traditional Ainu relationship with nature and the concept of kamui within the Ainu belief system.

Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi, ‘Genzai no Ainu Seisaku no Susumekata nit suite no Ikensho’, May 2018 (accessed 20 June 2018); Hokkaido Shinbun, 11 May 2018.

See, for example, Seok Soon-hi, ‘Kindaiki Chōsenjin to Teijūka no Keitai Katei to Ainu Minzoku: Awaji, Naruto kara Hidaka e no Ijū ni Kanshite’, Ajia Taiheiyō Rebyū [Asia Pacific Review], no 12, 2015, pp. 17–26, particularly p. 23.

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku Kankei Shiryō’, p. 9.

See Karafuto Ainu-Shi Kenkyūkai ed., Tsuishikari no Ishibumi: Karafuto Ainu Kyōsei Ijū no Rekishi, Sapporo, Hokkaidō Shuppan Kikaku Sentā, 1992; also Tazawa Mamoru, ‘Keishi Saretsuzukeru Enchiw’, in Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi ed., Seikai Hyōjun no Senjū Minzoku Seisaku o Jitsugen Shiyou! Sapporo, Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi, 2018, p. 9; Karafuto Ainu commonly refer to themselves as ‘Enchiw’, a word which, like ‘Ainu’, means ‘person; human being’.

See, for example, Morris Low, ‘Physical Anthropology in Japan: The Ainu and the Search for the Origins of the Japanese’, Current Anthropology, vol. 53, supplement 5, 2012, pp. 57–68, particularly pp. 60–61.

See Ueki Tetsuya, Gakumon no Bōryoku: Ainu Bochi wa naze Abakareta ka, Yokohama, Shunpūsha, 2008.

Kotan Association / Hokkaido University Information Research Disclosure Group, Ancestral Repatriation 85 Years Later: Ainu Ancestral Remains Return to Kineusu Kotan, documentary film, dir. Tomoaki Fujino, 2017; Shimizu Yūji, ‘Ainu Ikotsu no Songen aru Henkan no tame ni’, in Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi ed., Seikai Hyōjun no Senjū Minzoku Seisaku o Jitsugen Shiyou! p. 8; presentation by Shimizu Yūji and Kuzuno Tsugio at the International Workshop ‘The Long Journey Home: The Repatriation of Indigenous Remains across the Frontiers of Asia and the Pacific’, Canberra, Australian National University, 7–8 May 2018.

For example, the US Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, states that remains should be returned to the lineal descendants of the dead, or, if descendants cannot be identified, to the indigenous group from whose land they were taken, or the indigenous group which can claim the closest cultural affiliation to the remains; In Australia, where issues of repatriation are also central to the indigenous rights struggle, the government’s Advisory Committee for Indigenous Repatriation – all of whose members are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island people – produced a 2014 report on an Australian National Resting Place for indigenous remains which emphasised that this should only be for remains about which nothing is known except the fact that they come from Australia. In all other cases, remains should be returned to their communities of origin or, if these are unknown, to institutions in the region from which they came, which should continue the task of trying to identify the communities of origin; Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act [2006 edition] (accessed 22 June 2018); Advisory Committee for Indigenous Repatriation, National Resting Place Consultation Report, 2014, Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia, 2015.

Edward Halealoha Ayau and Honor Keeler, ‘Injustice, Human Rights, and Intellectual Savagery: A Review’, H/Soz/Kult Kommunikation und Fachinformation für die Geschichtswissenschaften, April 2017 (accessed 22 June 2018).

Ainu Seisaku Shuishin Kaigi, ‘Dai-10 Kai Ainu Seisaku Suishin Kaigi Seisaku Suishin Sagyō Bukai Hōkoku’, pp. 6–8.

See United Nations Economic and Social Council, Commission on Human Rights, ‘Standard Setting Activities: Evolution of Standards Concerning the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – Human Genome Diversity Researcn and Indigenous Peoples’, 4 June 1998, E/CN.4/Sub.2/AC.4/1998/4, p. 11.

Noboru Adachi, Tsuneo Kakuda, Ryohei Takahashi, Hideaki Kanzawa-Kiriyama and Ken-ichi Shinoda, ‘Ethnic Derivation of the Ainu Inferred from Ancient Mitochondrial DNA Data’, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, vol. 165, issue 1, January 2018, pp. 139–148.

See the letter of protest sent by Shimizu Yūji, Tonohira Yoshihiko, Ogawa Ryūkichi and others to the University of Yamanashi and the National Museum of Nature and Science on 14 May 2018. As well as raising questions about the lack of informed consent from the relevant Ainu communities, this letter questioned the researchers’ crucial assumption that the skeletons they studied were all of people buried during the Edo period (1603–1868). Documents relating to over 30 skeletons from a graveyard in Urakawa indicate that the Ainu skeletons unearthed from that site are modern (post-1868). In July 2018 the National Museum of Nature and Science and the University of Yamanashi sent two separate but identical replies to the letter of protest, without adequately addressing the issues raised. They stated that the research was conducted ‘in a manner that, as of 2007, was thought to respect indigenous rights. Thereafter we carried out [the research] without fundamentally altering our approach, which we consider also conforms to government policies’. This statement is clearly at odds with the ethical approaches set out by UN bodies in the 1990s and by bodies like the American Association of Physical Anthropologists well before 2007. For copies of the letter of protest and the two replies, see here (accessed 24 October 2018).

See Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi ed., Seikai Hyōjun no Senjū Minzoku Seisaku o Jitsugen Shiyou!

Hatakeyama Satoshi, ‘Umi no Shigen ni taisuru Kenri’, in Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi ed., Seikai Hyōjun no Senjū Minzoku Seisaku o Jitsugen Shiyou! p. 15.

Tazawa Mamoru, ‘Keishi Saretsuzukeru Enchiw’, in Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi ed., Seikai Hyōjun no Senjū Minzoku Seisaku o Jitsugen Shiyou! p. 9.

Inoue Katsuo, ‘Mikan no Ainu Minzoku Kyōyū Zaisan Mondai’, in Ainu Seisaku Kentō Shimin Kaigi ed., Seikai Hyōjun no Senjū Minzoku Seisaku o Jitsugen Shiyou! p. 7.

‘The Larrakia Declaration on the Development of Indigenous Tourism’, March 2012 (accessed 25 May 2018).

Craig Martin, ‘Striking the Right Balance: Hate Speech Laws in Japan, the United States and Canada’, Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, vol. 45, no 3, Spring 2018, pp. 455–532, citation from p. 468.