Abstract

Through a historical analysis of Japanese constitutions and key constitutional drafts from the Meiji Era to the present day, this article examines the relationship between the constitution of Japan and the rights of indigenous peoples. In recent decades, the constitutions of a number of countries have introduced clauses recognizing the culture or rights of indigenous people, but this still remains a lacuna in Japanese constitutional debates. After examining the continuing social problems which result from this lack of constitutional recognition, particularly from the perspective of the Ainu and Ryūkyū peoples, the article concludes with a call to oppose current government schemes for constitutional change by putting forward a radical alternative proposal to revise the constitution in a way that would recognize and celebrate Japan’s ethnic, historical and cultural pluralism.

Keywords

Indigenous peoples; constitution; human rights; pluralism; Japan; Ainu; Okinawa.

Modern Japan and its Basic Laws

2018 marks the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration, an event generally seen as initiating the construction of a “modern state” which imported its political and legal system from the Western powers. The phrase bunmei kaika, used as a translation of “civilization” in Fukuzawa Yukichi’s “Outline of Civilization” (1875), became a term symbolic of the times. In the 1870s, the Family Registration Act (1871), the Military Conscription Ordinance (1871), and the Land Tax Reform (1873) were all promulgated and implemented, while railroads and telegraph were both initiated as early as 1872.

Strictly speaking, though, the characteristics of the political and administrative system of this time can be thought of as a modern revival of the Heian period imperial government system of the 8th-12th century (the ritsuryō system), rather than as westernization. As in the ancient ritsuryō system, the six ministries, Civil Affairs, Treasury, Military Affairs, Prisons, Imperial Household, and Foreign Affairs, and also the Great Council (created in 1869) were placed under the institutional authority of the emperor, and their officers were nominally appointed by the Emperor himself. In the 1880s, a westernized form of nation-building finally became clearly distinguishable; that is, the “Western exterior” of the traditional nation based on the ritsuryō system took on a recognizable shape. Beginning with the Imperial Rescript to establish the Diet (1881), the 1880s saw the creation of the cabinet system (1885), the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution and of the House of Representatives Election Law (both in 1889), and implementation of the constitution and opening of the Diet (both in 1890).

The basic laws of the modern nation of Japan, born of the history that emerged from this era, are contained in the following two documents, which were enduring, in the sense that neither ever underwent revision and they thus possessed the character of “eternal texts”1: the 1890 “Constitution of the Empire of Japan” (containing 7 chapters and 76 articles) and the 1947 “Constitution of Japan” (containing 11 chapters and 103 articles). In this essay, we consider the rights of indigenous peoples through an analysis centered on these two constitutions.

But it is also important to consider the alternatives that have been proposed. A number of private drafts were submitted during the preparatory debates about each constitution. For instance, in the Meiji Period, drafts called “private constitutions” were published, most of them in 1881, by Ueki Emori, Fukuchi Genichirō, Nishi Amane and others. In the case of the postwar Constitution of Japan, a draft constitution (1945) was drawn up by the Constitutional Study Group formed in 1945 by Takano Iwasaburō and Suzuki Yasuzō, and in 1946, by the Japan Liberal Party. The Progressive Party, the Socialist Party, and Communist Party also all compiled and published separate drafts. Finally, in addition to these, in the current constitutional amendment debate, the “Draft Amendment of the Japanese Constitution” announced by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in 2012 (containing 11 chapters and 102 articles) has become the focus of controversy.

As well as analyzing the two constitutions which were actually put into effect, we will consider two private drafts which, in different ways, cast important light on Japan’s constitutional possibilities and challenges: Ueki Emori’s 1881 “Draft of the National Constitution for Great Japan of the East” (which contained 18 sections and 220 articles) and the 2012 Draft Amendment to the Constitution of Japan compiled by the Constitutional Reform Promotion Headquarters of the Liberal Democratic Party. Through this analysis, we examine the larger context and significance of the relationship between the constitution of Japan and the rights of indigenous peoples.

The main point we wish to emphasize is the fact that, in all of the four constitutional models covered in this article (and in the other drafts from this period from the Meiji Era to the present day), there is no clause concerning multicultural / multi-ethnic society or pluralistic citizen’s rights. In recent decades, a number of constitutions (such as those of Canada, Norway, Sweden and Finland) have introduced clauses recognizing the culture or rights of indigenous people, but this still remains a lacuna in Japanese constitutional debates. This is both a cause and a consequence of the indifference of the Japanese government, and of the majority of citizens, to the reality of Japan’s multicultural / multi-ethnic society. It is also both cause and consequence of the situation in which there is no constitutional foundation upon which to consider Japan’s indigenous peoples and their rights. Based on this premise, we discuss the merits and shortcomings of the current Japanese Constitution from the point of view of the rights of indigenous peoples.

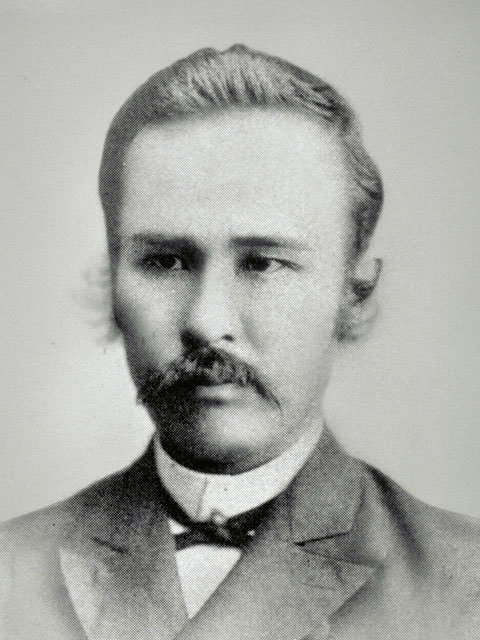

The Draft of the National Constitution for Great Japan of the East and Pluralism

We begin by considering the “Draft of the National Constitution for Great Japan of the East”, compiled in 1881 by Ueki Emori (1857 ~ 1892), because, to borrow from the words of historian Ienaga Saburō, Ueki’s remains the only one of the existing constitutional concepts to model Japan within a framework of pluralism.2 Ueki was a founding member of the political organization Risshisha (1874 ~1883), which played a central role in the Freedom and Popular Rights movement [Jiyū Minken Undō], and was also a member of the Risshisha Constitutional Investigation Bureau’s Drafting Committee. Ueki was a prudent Asianist, cautious about expanding national power through the use of force, His draft, though, is considered to be the most democratic / radical amongst the “private constitutions” of the time. While embracing constitutional monarchy, it is also known for clarifying the rights to democracy (Article 40), freedom (Article 5, Article 43 etc.), resistance (Article 64, Article 70), and revolution (Article 72)3. In addition, it is said that Takano, Suzuki et al. used Ueki’s manuscript as reference material for their 1945 “Constitution Draft Summary”. Ienaga evaluated Ueki’s draft as “the most democratic amongst all existing constitutional visions” in Japan.4

A crucial feature of Ueki’s draft is his concept of a federal nation state for Japan (Article 7), modeled upon the United States and Switzerland, and consisting of seventy independent state governments and a federal government. Articles 7 to 39 consist of provisions concerning the relationship between the federal government and the states, and specify state land rights (Article 14), as well as other points, in detail. Although Ueki’s draft contains a “Ryūkyū State”, Hokkaido is not envisaged as a “state”, and in this respect we can detect a marked ambiguity of territorial awareness in the early Meiji period5. In other words, the renaming in 1869 of the so-called “Land of Ezo” as “Hokkaido” effectively meant the colonization of the territory of the Ainu people, Ainu Mosiri, by the modern state. A parallel act of colonization occurred in the 1879 renaming of the Kingdom of the Ryūkyūs as “Okinawa Prefecture”. It is interesting that, while Ueki did not recognize Hokkaido as an independent area which should be treated as a “state”, he used the name “Ryūkyūs” and recognized their “statehood” (that is, their status as a province with considerable powers of autonomy) even after Okinawa Prefecture had been established.

Another important point in considering the constitution from the perspective of pluralism is the position of the emperor. Unlike the political position of the presidents of the United States and France, the emperor is simultaneously both a political and a religious institution of a specific ethnic group: the Yamato people. In other words, the Japanese emperor system is historically located outside of the Ainu or Ryūkyūan world. On that point, to Ueki’s credit, the “Draft of the National Constitution for Great Japan of the East” uses the term kōtei (the word used to translate the title of the emperors of other countries)6 rather than the (exclusively Japanese and Shintō based) tennō, and, while Articles 75 to 113 of Part 5 deal with the “Emperor and Imperial Regency”, the “emperor” is defined as a personage with authority limited solely to control over the federal government. Given the presence of other cultures and ethnic groups within the nation, this system would have reduced the oppressive nature of such sovereign power.

The “Constitution of the Empire of Japan” and the Emperor System

By contrast, Japan’s first constitution, the Constitution of the Empire of Japan, drafted by the Japanese government centered around Itō Hirobumi, was presented by the Meiji Emperor to Prime Minister Kuroda Kiyotaka in 1889, and promulgated as a constitution bestowed by the sovereign. By this time the Ainu people, having been distinguished in the 1871 Family Register by the derogatory label “Former Aborigines”, had been incorporated into the Japanese state as “commoners” in the new family registration system [known as the jinshin koseki] which was initiated in the following year. Meanwhile, in 1879 the Japanese government had completed the so-called Ryūkyū Shobun (Disposal) crushing the resistance of the Ryūkyū Kingdom and establishing Okinawa Prefecture via annexation. Thus, under the Constitution of the Empire of Japan, the problems of the Ainu nation and Ryūkyū people existed as a matter of fact, but the solution which the constitution proffered to these issues was the very simple expedient of completely neglecting them in its legal framework.

Unlike Ueki’s draft constitutional proposal, the Constitution of the Empire of Japan (which was modeled on the Constitution of Prussia) enshrined the Emperor (Tennō) from the start in its first chapter (Articles 1–17), prescribing “Imperial Sovereignty” in Article 1: “The Empire of Japan shall be reigned over and governed by a line of Emperors unbroken for ages eternal”. As mentioned above, following upon the model of Britain, a cabinet system had already been put in place in 1885 in Japan, but in order to realize a stronger imperial sovereignty, the constitution stipulated a “Minister of State” without ever even mentioning a cabinet system. In other words, under its provisions, the emperor held the position of head of state and exercised power over government on the advice of the minister of state. For example, the emperor appointed the prime minister to select the cabinet, and the cabinet had responsibility only to the emperor. Juridical powers were delegated to the courts in the name of the emperor, and he also commanded the army and navy. In return, residents of the empire, within the limits of the laws enacted by the emperor with the support of parliament, were guaranteed certain rights as subjects of the monarchy. Under this system, the forced incorporation of a number of non-Yamato ethnic groups was carried out through the “disposal” of the Ryūkyūs, the “acquisition” of Taiwan in 1895, the “Former Aborigines Protection Act” of 1899, and the annexation of Korea in 1910; but the diversity of these colonies and of Japan’s domestic indigenous peoples was simply incorporated under the absolute power of the “Emperor’s Sovereignty”, with no revision to the Constitution, but rather through extra-constitutional measures.

For example, in the formal colonies, the coercive powers of the emperor system embodied in imperial ordinances and “standardized law”7 made possible a constitutionally “un-problematic” (yet thoroughly discriminatory) regulation of the relationship between the emperor and his subjects. On the lands of domestic indigenous peoples, the same objective was accomplished through forced assimilation policies. To give one example, in 1915, under the local system of the colony of Karafuto (Sakhalin), villages and towns were organized under “Imperial Decree No.101”, and in 1918, mainland Japanese law became applicable to the colony under the standardized law, which had just come into force. In 1920 it became possible to apply the provisions of mainland Japanese law to Karafuto via “Imperial Decree No. 124”, and finally, in 1943, with the abolition of the same decree, Karafuto was fully incorporated into Japan’s domestic territories. In the process, unlike the Ainu on the main island of Hokkaido, who became Japanese citizens, Sakhalin Ainu until 1932 were designated as “Karafuto Aborigines” under the Karafuto Family Register, only later to be incorporated into the same mainland Japanese Family Register system as the Hokkaido Ainu.

As far as the Ryūkyūs were concerned, due to purported reasons such as the Okinawan subjects’ “lack of loyalty” or “low degree of civilization”, there were arbitrary delays in enforcing of mainland Japanese law, and Okinawa was given the designation, so characteristic of colonialism, of an “anomalous region”; but the legal inconsistency of these processes were never questioned in terms of the constitution. For instance, the 1871 Military Conscription Ordinance was enforced in the main island area of Okinawa only in 1898, after the Sino-Japanese War, and only in 1902 was it enforced in the Sakishima Islands surrounding Ishigaki Island. Similarly, the House of Representatives Election Law of 1889 which stipulated the right of suffrage, a fundamental right of subjects, was only amended and applied to Okinawa Prefecture in 1912, and its application to the Sakishima Islands was delayed even further until 1919. Additionally, the Japanese Government enforced the Okinawa Prefecture Land Reorganization Law in 1899 and embarked on efforts to reform the land tax, but the land reorganization project was not completed until 1903, and meanwhile, the Okinawa Prefecture and Islands Towns and Villages Decree (Decree No. 40 of 1907), which established a special local administrative system for Okinawa Prefecture, was not enacted until 1908. Decree No. 40 that designated this regional system was abolished only in 1920, when the local system of Okinawa Prefecture became “equal” with the that of the “mainland”. Meanwhile in Hokkaido, in a policy which targeted not only Ainu people but other residents, the establishment of an equal system with the mainland was similarly greatly delayed, in effect creating an “anomalous area” of the sort used by the Japanese government to delineate its colonies8.

Such declarations and imperial decrees repeatedly presented the political fiction of the perpetuity and eternity of the Imperial family from ancient times as the legitimating principle of modern state sovereignty. For instance, a phrase from the Imperial Proclamation of the Constitution clearly states that Japan has persisted as an Empire since the times of the Goddess Amaterasu and Emperor Jimmu: “The Imperial Founder of Our House and Our other Imperial Ancestors, by the help and support of the forefathers of Our subjects, laid the foundation of Our Empire upon a basis, which is to last forever”. But in the context of such a vision, for those subjects who did not accept this religious ideology, even the “grace and favor” rights conferred on them were only arbitrarily protected. Under this structure, the Ainu people, despite their ethnic difference, were seen as gradually assimilating subjects (Former Aborigines) of the Empire, and the Ryūkyū people, as “Okinawan citizens”, were viewed as a group of subjects of the ancient Empire who had been absorbed by a process of ethnic integration. Neither was officially recognized as having their own distinctive sets of rights based on their own history, and both were subjected to severe discrimination.

|

|

The Constitution of Japan: Hopes and Harsh Realities

Current constitutional debates in Japan focus on proposals put forward by the Liberal Democratic Party for the amendment of the postwar Constitution of Japan, and particularly highlight the revisions of the constitution’s “peace clause” embodied in this proposal. Here we re-examine the nature of the existing postwar constitution from the perspectives of pluralism and indigenous rights, before going on to argue for an alternative strategy to counter the multiple negative features of the LDPs proposed revisions.

1) The Postwar Constitution, Japan’s Constitutional Scholars and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights

The Constitution of Japan which came into effect in 1947 essentially ignored issues of multiculturalism, multi-ethnicity and the rights of indigenous peoples. The premise behind its basic structure is exactly the same single, homogeneous political and administrative system as was presupposed by the Meiji era Constitution of the Empire of Japan and re-inscribed (as we shall see) in the LDP’s 2012 draft revised constitution. For example, in Article 1 of Chapter 1 of the postwar constitution, the emperor, although not the head of state, is still depicted as “the symbol of the national integration of Japan”. Moreover, the content of Articles 10 to 40 of Chapter 3—Citizens’ Rights and Obligations – which clearly lays outs the rights and responsibilities of citizens, is surprisingly similar to the content of the 2012 LDP draft for a new constitution.

Japanese constitutional scholars, in defending the postwar constitution, have been remarkably indifferent to the situation of Ainu and other indigenous people and to the conditions of pluralism. For example, even Miyazawa Toshiyoshi and Itō Masami, prominent and conscientious constitutional scholars, make such statements as the following (this from Miyazawa in 1967):

To discriminate by race means, for example, restricting the legal capacity of Ainu in the sphere of private law more than that of average citizens…In Japan, racial differences are small, so racial discrimination has not become a serious problem, but there are many cases in foreign countries.9

Campaigns by the Ainu people for a “New Ainu Law” as well as for the abolition of the discriminatory Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act took place in 1984, but these did not alter the views of Miyazawa (who had been one of the founders of the Constitutional Problem Study Group, created in 1958 in order to disseminate the values of the postwar Constitution of Japan). In 1994 he was still saying: “There is little difference in race among Japanese citizens, so discrimination on the grounds of race has never been a problem in Japan.”10

Meanwhile, Itō Masami, a constitutional scholar who served as a justice of the Supreme Court as well as chairperson of the 1995 Expert Council on Utari Countermeasures (discussed further below), made the following statement in 2006: “Currently, as there are few people of different races subject to Japanese rule, so the problem (of the recognition of Ainu people as having their own ethnicity under the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act) is less than in other countries.”11

On the other hand, Ebashi Takashi who, unusually amongst constitutional scholars, has commented and acted on Ainu issues, criticized this perspective as follows in a paper entitled, “Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Constitution of Japan”:

Discrimination against the Ainu people has been almost ignored in interpretations of the Constitution of Japan by constitutional scholars … After Ainu individuals and activist groups raised their voices expressing grief at continued discrimination, the problem surfaced in the United Nations Human Rights Sub-Commission and ILO and other bodies. In addition, discrimination against Ainu people has been identified by government and other studies. If most of the literature continues to keep silent even after that, this reflects a shameful ignorance of hundreds of thousands of human rights violations.12

Yet none of the six volumes of the Iwanami Series—Constitution, a major work on the subject published by Iwanami Shoten in 2007 and written mainly by the young constitutional scholars Hasebe Yasuo and Doi Shin’ichi – takes up the issue of multiculturalism and diverse ethnic groups in Japan and its constitution.

The key point about this situation is that constitutional scholars tend to see the reasons for the problem of the neglect of minority ethnic groups in Japan as lying in the fact that their numbers are small in relation to the total number of nationals, and simultaneously to construe this issue only in terms of the principle of “equality under the law”. In other words, for these scholars, there is no fundamental distinction between indigenous people and others, and there would be no problem if it were not for the fact that their numbers are small. These scholars do not even try to imagine, let alone try to try to address, indigenous peoples’ distinctive history and culture and the unique rights demands which stem from these. Kayano Shigeru, a person of Ainu ethnicity who served in the Japanese Diet, criticised Japan’s “democratic” system, including the constitution, for its “violence of numbers”13. What is completely missing from this analysis is that the violence inflicted by the principle of majority rule is also a post-colonial problem: an issue of indifference to the colonialism and colonial responsibility which created this situation in the first place14. To put it another way, the problem is not simply that Ainu are a small minority in Japan, but that they are a minority whose (quite large) land was appropriated by the Japanese state without their consent.

2) The Constitution of Japan and Indigenous Peoples: The Case of the Ainu

Nevertheless, the Ainu, and also the Ryūkyū people (the emergence of debates about indigenous rights and rights to self-determination rights in the Ryūkyū context), also put their hopes in the postwar Constitution of Japan. This is because, compared with other basic laws or constitutional concepts, some possibilities and hopes of realizing their rights, however slight, appear to exist in this constitution.

For example, in the case of the Ainu people, these hopes can be seen in the movement for the enactment of the New Ainu Law. In 1984, the Draft for a New Ainu Law was passed by the General Assembly of the then Hokkaido Utari Association (now the Hokkaido Ainu Association), demanding the abolition of the 1899 Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act and calling for legislation that stipulated the rights of the Ainu people. In its “Preamble: Reason for Establishing this Law”, the draft refers to the Constitution of Japan as follows:

This law aims to recognize the existence of the Ainu people, who possess a culture unique in Japan, to ensure respect for their pride and establish a guarantee of their rights as a people on the basis of the Constitution of Japan …The Ainu ethnic problem is a shameful historical product of the processes of creation of the modern state of Japan, and embodies important issues related to fundamental human rights guaranteed by the Constitution of Japan. Recognizing that it is the government’s responsibility to solve such a situation, and that this is an issue for all citizens, we hereby abolish the humiliating Ainu racial discrimination law, the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act, and enact a new law concerning the Ainu people.15

This demand for a new law, drafted by the Ainu people themselves, located their problem within a very simple structure: it highlighted the lack of rights and of policies which should, as a matter of course, be assured to the Ainu people, and it defined this situation as an infringement of fundamental human rights that the Constitution of Japan is supposed to guarantee. Thus, the duty and responsibility to actualize these rights and policies is located in the constitution. In this way, instead of brandishing the grandiloquent interpretations of constitutional scholars, the Ainu people appealed directly to the fundamental principles of the constitution and demanded a new legal framework to address Ainu issues.

Following this movement, the Japanese government responded with what has since become a pattern in regard to Ainu affairs: a “council of experts” is established as an advisory body in the Cabinet Secretariat, the council submits a report, and the government implements policies in response to the recommendations of the report. In 1995 and 2008, the councils established, respectively, were the Expert Panel on Utari Policy (composed of seven members chaired by Itō Masami; hereinafter referred to as the Utari Panel), and the Expert Panel on Ainu Policy (composed of eight members chaired by Satō Kōji; hereinafter referred to as the Ainu Panel).

Though established separately, both groups were similar in composition. First, the chairpersons, Itō Masami and Satō Kōji, are both giants in the field of constitutional law, authorities from the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University, respectively16. Next, one of the committee members has inevitably been a constitutional scholar from the University of Hokkaido; in the Utari Panel this council member was Nakamura Mutsuo, former President of the University of Hokkaido and currently serving Chairperson of the Foundation for the Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture; in the Ainu Panel it is Nakamura’s leading disciple, Tsunemoto Teruki, the current Director of the Hokkaido University Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies. One of the main reasons for including these people was that, from the perspective of the constitution, which contains no specific recognition of the distinct history and special rights of the Ainu people or other indigenous peoples, it is deemed essential to have rulings or interpretations from constitutional scholars themselves in order to advance the issue. A telling example of this reliance on legal experts to provide constitutional interpretation can be found in the fact that, following the presentation of the Draft for the New Ainu Law, a “Committee to Examine the Issue of the Ainu New Law” consisting of administrators at the section head level from ten separate ministries and agencies related to Ainu issues, was established in 1989, only to be disbanded in 1995 on formation of the Utari Panel, without ever having reached a single conclusion. Apparently, the task of formulating Ainu policy was beyond the abilities even of bureaucrats from the central government without input from constitutional experts.

In any event, constitutional scholars in general have not shown increasing interest in the issue in recent years, nor has the discussion deepened, and it can thus be said with only slight exaggeration that the Japanese government’s approach to the indigenous peoples’ issue under the provisions of the Japanese constitution is actually being decided by two constitutional studies authorities and two constitutional law scholars from Hokkaido University.

The Utari Panel submitted a report in the year following its formation (1996), the content of which, as summarized by its Chairperson, Itō Masami, was broadly as follows: First, the panel recognized the Ainu’s “indigeneity / ethnicity” as a historical fact, but noted that that there were serious conflicts in various countries of the world over the definition of indigenous peoples, collective rights, individual human rights and the handling of self-determination rights, etc. In setting out new policies, the council considered that “it [was] necessary to make judgments in line with the actual circumstances of our country.” Secondly (with something of a leap in logic), the panel proposed that the aim should be “the realization of a society wherein the ethnic pride of the Ainu people is respected and the further development of national culture is advanced through the preservation and promotion of Ainu language and Ainu traditional culture and through fostering understanding of the Ainu people”17.

In July 1997, following this recommendation, the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act became law; but this was premised on the assumptions set out above: that in the “actual circumstances of our country” it is possible to create a society that respects Ainu pride merely through the promotion of Ainu culture. This was a major step back from the Ainu ethnic rights – i.e. indigenous rights – which Ainu groups had demanded in their Draft for a New Ainu Law. It should also be noted that another important event of 1997 was the handing down of the Nibutani Dam judgment. In this ruling on a case in which Ainu plaintiffs sued over the construction of a dam which would destroy culturally significant sites, the Sapporo District Court became the first official body to recognize the Ainu people as indigenous. However, this ruling also had limitations which are discussed below.

Subsequently, in June 2008, both Houses of the Diet adopted a “Resolution Seeking to Recognize the Ainu as an Indigenous People”, which led to the establishment of the Expert Council on Ainu Policy in the same year, but in the resolution itself there is no wording referring to the Constitution of Japan. Instead, it called for “further promotion of the Ainu policy [enacted] so far and the establishment of comprehensive measures” with reference to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples18 adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 2007, the previous year.

The report of the Ainu Panel, on which Satō himself served as chairperson, was submitted in July 2009. Its core content can be summarized into four points. Firstly, the panel plunged into an in-depth history of the Ainu people. In Satō’s own words, “in order to develop a forthright new policy, the council could not avoid making an evaluation of history.”19 Secondly, based on its historical evaluation, the council concluded that, considering the serious damage which modernization policy had inflicted on Ainu culture, the Japanese government “has a strong responsibility to pay serious attention to the restoration of the culture of the indigenous Ainu people”20. Thirdly, “culture” is interpreted in the report in the broad sense of the “entire lifestyle,” specific to the Ainu people, including land use. Lastly, the fourth point is that “restoration of culture” encompasses the creation of a “new Ainu culture” for the future21.

Following the recommendations of this report, in December of 2009, the government established an “Ainu Policy Promotion Council” with the Cabinet Secretary as chair. This council was entrusted with a mission to advance two major initiatives: a project for the creation of a “Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony” and a “Survey of the Living Conditions of Ainu Living Outside of Hokkaido”. As a constitutional basis for such a policy, Satō turns to Article 13 of the Constitution of Japan, which states, “all of the people shall be respected as individuals. Their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness shall, to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare, be the supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs”.

Satō then introduces the following interpretation of this constitutional requirement:

Recognizing that a fundamental value for each person lies in pursuing his/her own happiness and living to the full as an autonomous being, we strive for a society and nation which will allow people to coexist while respecting this value to the greatest extent, and we envisage the guarantee of basic rights to each person from this point of view.22

In other words, Article 13 stipulates people’s “rights to personal autonomy” including “the right to the pursuit of happiness” as a moral right, and this includes the right for the Ainu to live as Ainu. According to this interpretation, Ainu ethnic policy further establishes a legal right which accords with the fundamental human rights of Article 11, and is supported by Article 97 of the “supreme law”23. The 1997 Nibutani Dam judgment also applies Article 13 of the Japanese Constitution, and Tsunemoto Teruki has evaluated this Article as “providing a context in which individuals belonging to an ethnic group can choose their way of life.”24

But in these cases, Ainu policy as construed in terms of the constitution depends not upon clear stipulations found in the actual constitution itself, but rather on the interpretations of a handful of constitutional scholars. Moreover, Article 13 of the constitution clearly deals with the human rights of individuals (not of groups), and does so only to the extent that this “does not interfere with the public welfare”. In other words, while the criteria of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples emphasizes the centrality of collective rights, Ainu policy falls at the exact opposite end of the spectrum: it is presented as a matter of the rights of individuals to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”. Tsunemoto came to refer to this unique rights policy in 2010 as “Japanese-style Indigenous Peoples’ Policy”25. Not surprisingly, this idea has become an extremely effective back-up for the Japanese government, particularly for central government bureaucrats who are reluctant to support group rights.

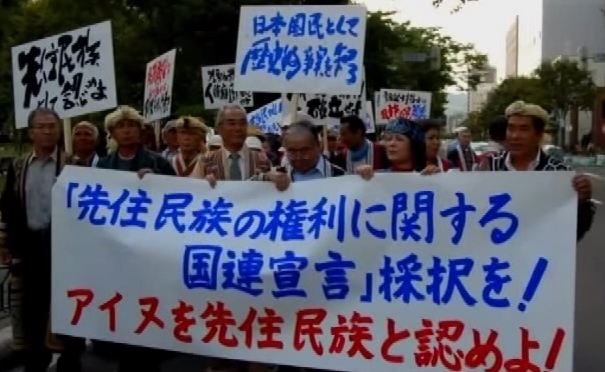

Demonstrators call for official recognition of the Ainu’s rights as indigenous peoples. |

3) The Constitution of Japan and Indigenous Peoples: The Case of the Ryūkyū People

The relationship between the Ryūkyū/Okinawan people and the postwar Constitution of Japan is further complicated by the direct intervention of the United States. At the same time, expectations by the Ryūkyū people toward the Constitution of Japan were as high, or perhaps even higher, than those of the Ainu. In March 1945, with the onset of the Battle of Okinawa, the US military promulgated the Nimitz Decree (US Navy Decree No. 1) which terminated the administrative power of the Japanese government over the territory of the former Ryūkyū Kingdom. After occupation by the American military, this territory came under the direct military control of the U.S. Army, and was thus outside the scope of Japanese rule. Although the name for this system of government was to change from the “United States Military Government of the Ryūkyū Islands” (1945 to 1950), to the “United States Civil Administration of the Ryūkyū Islands” (1950 to 1972), in essence the structure was always one of occupation by the US Army, with those serving as the heads of government—the “Military Governor”, “Governor”, and “High Commissioner—all being military personnel.

This Nimitz Decree was approved by the Japanese government itself at the 89th Imperial Diet of November 1945, held after defeat in the war. Simultaneously, the House of Representatives Election Law was revised, and in the general election of the House of Representatives on the 22nd of April 1946, at the same time that women’s suffrage was achieved, the right to vote of “Okinawan citizens” (and of former colonial subjects living both in Okinawa Prefecture and throughout Japan) was peremptorily terminated. During the 90th Imperial Diet session (June – October 1946), the draft of the Constitution of Japan underwent domestic scrutiny by serving Diet members, but at this time there were no parliamentarians elected from “Okinawa Prefecture” present. In effect, the Ryūkyūs/Okinawa was excluded by the decision of the Imperial Diet which accepted the Nimitz Decree, and, as a US military colony, was outside the Constitution of Japan which came into force in 1947.

Initially, the US military encouraged the inflated expectations of Ryūkyū residents, who hoped for the realization of democracy by the US in place of Japanese colonial rule. When those expectations were betrayed, however, a new social movement began in the Ryūkyūs. This movement defined Japan as the “motherland” and the US military as ethnic others – colonizers who did not even speak the language of the colonized – and placed its hopes in the pacifism of the Japanese constitution. The aim was thus the revival of Okinawa Prefecture under Japanese jurisdiction. At the movement’s center was the Okinawa Prefecture Reversion Council, formed in 1960, with goals which included “national unity” against “rule by foreigners”. This reversion movement, though, was not in reality a movement centering around Okinawan identity itself, but was rather an anti-war / anti-base crusade opposing oppression by the US military, and seeking protection from Japan’s peace constitution. When actual reversion to the “motherland” approached and it became clear that the condition after return would be the preservation of the US military bases, expectation changed to pervasive disappointment. This can be seen in the emergence of “anti-reversionism”26, which gained growing support in some circles just before reversion. It can also be seen in the fact that the members of the Okinawa Prefecture Reversion Council themselves were absent from the ceremony of reversion to the motherland, celebrating the return of Okinawa to Japan on May 15, 1972. In any case, on that day, Okinawa Prefecture was revived as a unit of local government and reintegrated under the Constitution of Japan. At the same time, the vast area of US military bases remained, its legal status redefined under the Japan-US Security Treaty.

After the reversion of Okinawa to Japan, the issue of the US military bases in Okinawa was seen by many Okinawan critics as a problem created by the conservative LDP government, which was subordinate to the United States. Following reversion, Okinawan progressives joined with mainland progressives in the anti-security treaty movement. As its conceptual basis, this movement placed its hopes in the constitutional enshrinement of the right of peaceful survival (Preamble Section 2, Article 9, Article 13), the principle of equality (Article 14), respect for fundamental human rights (Chapter 3), and local autonomy (Article 95). For residents of the Ryūkyūs, the constitution thus became a valuable tool in their fight for the rights of the communities whose lives were dominated by the presence of US bases.

However, in August 1996, a legal struggle broke out between the Japanese government and Okinawa Prefecture over Governor Ōta Masahide’s refusal to give his proxy signature approving the forced use of land by the US military.27 At this time, the full bench of the Supreme Court ruled that the Act on Special Measures concerning US Forces Japan Land Release, which concerns the mandatory use of Ryūkyū land by the United States, was legal in terms of the Constitution of Japan. The Court proceeded to dismiss Ōta’s appeal on the grounds that Governor Ōta’s refusal to sign the leases would “significantly harm the public interest.” It should be kept in mind that this judgement was a unanimous one by the fifteen judges of the full bench of the Supreme Court, the institution which should be the guardian of the constitution28.

73.8% of US military-dedicated facilities are concentrated in Okinawa Prefecture which has only 0.6% of the nation’s land, and a wide range of abuses associated with the bases are occurring, with violations of freedom of expression, health rights, women’s rights etc. Yet, even though these abuses have often been highlighted, amongst the 475 members of the House of Representatives in the current Diet, only four members are elected from the Okinawa electoral district (five members of parliament from Okinawa also serve in the current Lower House, but are elected from a proportional representation bloc which includes Kyushu), and amongst 242 members of the House of Councilors, only two members are elected from the Okinawa electoral district, so voices calling for equality and human rights for Okinawa Prefecture are drowned out in the legislature. In this sense, even though the Okinawan situation is less extreme than that of the Ainu (who at present have no representatives in parliament), Kayano Shigeru’s claim about the “violence of numbers” is highly applicable to Okinawa as well. In the case of Okinawa, though, (as highlighted by the article by C. Douglas Lummis in this special issue) the problem is compounded by the way that the Security Treaty with the United States (Ampo) interacts with and (particularly in the case of Okinawa) impedes the application of the postwar constitution.29

On the other hand, Okinawan citizens were given hope by the promises of former Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio and his Democratic Party of Japan, which defeated the LDP and became the ruling party in September, 2009, after Hatoyama pledged to relocate the controversial Futenma Airbase “out of the country if possible, and at least to a different prefecture.” When Hatoyama visited Okinawa in May 2010, however, he instead disappointingly withdrew his pledge, apologetically stating that it was too difficult to relocate the base outside the prefecture. In the background to this development, it has been claimed that there was interference by bureaucrats from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense, non-cooperation within the Cabinet, criticisms of the plan by major media outlets as “unrealistic”, and so on: all of these, of course, were domestic problems within Japan itself, not problems of the US military. Under the same Democratic Party of Japan administration in February 2012, when the US government offered to relocate 1500 Okinawa-stationed Marine Corps troops to Iwakuni Base (Yamaguchi Prefecture), the Governor of Yamaguchi Prefecture and the Mayor of Iwakuni announced their opposition, and Foreign Minister Genba Kōichirō promptly announced his refusal to approve the transfer of the US military. In other words, the latter two cases show that the root of the problem could not simply be defined as lying either with the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, or with the “violence of numbers.”

In July 2014 an “All-Island Council to Realize the Demands of the Okinawa Petition and Open the Future”30 was created, going beyond Japan’s conservative versus progressive ideological frameworks. Then, in November of the same year, Governor Onaga Takeshi took office under the slogans “identity rather than ideology” and “richness of pride”. In September 2015, Onaga visited the United Nations Human Rights Council to read a statement that Okinawa’s right to self-determination under international law was being infringed, at the same time announcing the revocation of his government’s approval for the construction of the Henoko offshore base as a replacement for the Futenma Airbase. Governor Onaga’s decision to rescind the Henoko approval mobilized the right to local autonomy as a defense, but in December 2016 the Japanese government challenged this action in the courts, and in the ensuing court case, the second bench of the Supreme Court judged Onaga’s revocation of approval as illegal, dismissing the prefecture’s appeal and upholding the position of the Japanese government. This judgment too was a unanimous decision by the court’s four judges31.

Just as the Ainu people have relied on the interpretations of constitutional scholars, the Ryūkyū people, in the case of the courtroom battles, tried to mobilize the principles of the constitution itself. The Henoko Base opposition was also a fight by the Okinawa Prefectural Governor, who had been elected by the citizens of Okinawa. Yet, even when party control of the national government changed hands, no change in the situation occurred, and the “violence of numbers” in the National Diet could not be overturned by majority rule. Nor did the key organ of the judiciary, the Supreme Court, bring any improvement to the situation. Of course, there are still those experts who believe that such a situation would not occur if the Constitution of Japan were properly put into effect and duly respected. But if we face the facts, it is hard to deny that there is a major problem in the structure of the constitution itself. In other words, in the case of Okinawans as in the case of the Ainu, the rights of citizens are not being effectively protected by the postwar constitution’s general provisions on human rights, because these provisions fail to take account of Okinawa’s distinct history as a colonized area. This problem is further aggravated for Okinawa by the extra-constitutional powers embedded in the US-Japan Security Treaty.

The LDP’s 2012 Draft Amendment to the Constitution of Japan and the Denial of Pluralism

Now, let us turn to the LDP’s 2012 draft revised constitution, drawn up mainly by the Drafting Committee of the LDP’s Constitutional Reform Promotion Headquarters (under the chairmanship of Nakatani Gen), to show how this draft, far from amending the weaknesses of the postwar constitution, seriously aggravates them. The creation of an “autonomous constitution” has been part of the LDPs policy since the formation of the party in 1955, and this draft is described as embodying that aspiration.

It is often noted that the problematic point of this 2012 LDP draft is that the current Constitution of Japan’s “Chapter 2—Abandonment of War” has been rewritten as “Chapter 2 — Security”. The draft replaces the renunciation of military power and the denial of right to belligerency with a proclamation of the right to self-defense and the right to a national defense army, and also strengthens “citizen’s obligations” at the expense of “citizen’s rights.” However, from the standpoint of emphasizing multicultural / multi-ethnicity and pluralism, the issue central to this article, we also need to pay close attention to the full rewrite of the constitution’s preamble, which in a nutshell, departs radically from that of the postwar Constitution of Japan and becomes close to the preamble of the Meiji Constitution of the Empire of Japan. In short, the LDP draft preamble re-emphasizes the origins and traditional values of the state, rather than focusing on the reasons why the constitution was enacted.

For example, it states:

Japan is a nation with a long history and unique culture, having the Emperor as the symbol of the unity of the people and governed… The Japanese people will defend the nation and homeland with pride and strong spirit, and respecting fundamental human rights, value harmony and form a nation state where families and the whole society assist one another.32

This statement from the preamble re-asserts that Japan is a nation with “a long history and unique culture” centered on the emperor, and highlights the spirit of “harmony” that supposedly characterizes the collectivism unique to the Yamato people, as well as the spirit of cooperation embodied in “family and society”. The attribution of these characteristics to the nation is reinforced in “Chapter 1— The Emperor”, with its clauses on the Head of State, the national flag, the national anthem, and so on. Needless to say, if indigenous people were to accept such characteristics of the nation, it could only be on the premise of re-assimilation into the Yamato nation. The “Rights and Obligations of Nationals” are set out in Chapter 3, Articles 10 to 40. These cover the “enjoyment of basic human rights” (Article 10). Discrimination against the disabled has been added to the list of types of prohibited discrimination in terms of “equality under the law” (Article 14), and environmental protection [Section 2], protection of Japanese nationals living abroad [Section 3], and consideration for crime victims [Section 4] have been added to “the right to life” (Article 25). But the content of the principle of equality in this draft constitution is being pursued with almost no improvement in terms of addressing core issues of a multicultural society. From a critical perspective, this draft provides no innovative constitutional concept for the 21st century, only a return to the embrace of the Meiji Constitution of the Empire of Japan.

The important thing to remember about the LDP draft is its date of compilation: 2012. Already in 1997, the Nibutani Dam Judgment (Sapporo District Court) had been handed down, recognizing the Ainu as an indigenous people. In the same year, with the adoption of the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act33, Japan’s status as a multicultural society had been recognized (Article 1). In 2008, both Houses of the Diet had already passed the “Resolution Seeking to Recognize the Ainu as an Indigenous People”, and in response to this, in 2009 the Ainu Policy Promotion Council, with the Chief Cabinet Secretary as Chairperson, had been established. Although these were fragmentary, they were steps towards the creation of a multi-cultural society. But unfortunately – or perhaps we should see this as the essence of Japanese society – these developments are in no way reflected in the LDP 2012 draft. A single homogeneous political and administrative system is taken for granted.

The Limits of the Constitution of Japan in Terms of Indigenous Rights

In this article, we have sought to examine the Japanese constitution and the rights of indigenous peoples in relation to one another. Viewed in terms of this relationship, it is clear that there is a fundamental problem in realizing the rights of indigenous peoples under the constitution. So far, no constitutional concept which can overcome the problem has been put forward in Japan. As long as there is little prospect of such a new concept emerging, it is unfortunately necessary to defend the existing constitution from the point of view of its recognition of civic rights, as well as for other reasons.

But, this does not mean that we should close our eyes to the problem. The point is that we must confirm multicultural and multi-ethnic society as the fundamental direction for Japan, and also clarify the fact that reflection on past history, and particularly on the history of colonialism, is the basis of this process. For example, the preamble to the constitution should clearly describe both the good and bad sides of Japanese modernity. Furthermore, while expanding human rights according to international standards, it is essential to include explicit clauses in the constitution which are premised on the presence of minorities and indigenous groups, and which create both collective rights and a system of pluralism.

Personally speaking, we feel that, in the face of demands for constitutional amendment from conservative groups, the liberal side has simply been reacting in a defensive way. The defensive liberal side brings Article 9 to the fore, but does not raise issues of pluralism. It may be argued that this approach is pursued for strategic reasons, but as generations who do not directly know war expand, is this really a sound strategy? Instead, how about boldly producing a radical revised draft, as Ueki Emori did, but this time including pluralism, and using it to confront the conservative group? In that way, we think that it may be possible to involve citizens in wide-reaching discussions that shake the conservative government. However, in places into which we cannot delve deeply, we have an uneasy feeling that the essentially authoritarian structure of the postwar Japanese society is still alive and well: a structure which, with its notion of “an ethnically homogeneous nation state”, fails to see, or disdains, pluralistic society.

Notes

The phrase “Eternal Text” (i.e. a legal code so excellent that it never becomes obsolete) is sometimes used in reference to the postwar Constitution of Japan; even the Referendum Law which is the procedural law necessary for the revision of this constitution was not enacted until 2007.

Kobatake Takashi, “Ueki Emori no Kenpō Kōsō: Tōyō Dainippon Koku Kenpō Sōan” (Emori Ueki’s Concept of the Constitution) “Draft Proposal of the National Constitution for Great Japan of the East”, Bunka Kyōseigaku Kenkyū. (Okayama University Graduate School of Social Sciences and Humanities), 2008, Volume 6.

In Shiryō ni Miru Nihon no Kindai (Historical Materials on Modern Japan) 1-14, Ueki Emori no Kenpō Kōsō – Tōyō Dainippon Koku Kenpō Sōan (Emori Ueki’s Concept of the Constitution/Draft Proposal of the) National Constitution for Great Japan of the East Accessed 27 July, 2017.

In Ueki Emori’s draft, the regulation in Article 10 stating that “states which have not achieved independence will be under the jurisdiction of the federal government” is thought to refer to Hokkaido.

In other words, the head of state as existing in countries like the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Japanese: kōtei), rather than a sovereign imbued with a divine lineage (Japanese: tennō), as in the conception of State Shinto.

“Standardized Law” was a law enacted in 1918 to coordinate laws and regulations between the Japanese external colonies of Taiwan, Korea, Karafuto, Kwantung and Japan’s South Seas Mandate, and the Japanese mainland.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs Treaty Bureau’s “Foreign Legal Journal” published in 1957 (Volume 2 “Outline of Foreign Legal System”) (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs) defines colonies (foreign areas) as “anomalous areas” and lists Japanese colonies prior to 1943 as Taiwan, Korea, Kanto Province, the South Seas Mandate, and Karafuto. In relation to the land tax system, Hokkaido was also an anomalous area. The Japanese government started the modern tax system with the enforcement of the Land-tax Reform Ordinance (Chiso-Kaisei Jorei) in 1873. But this system was only introduced into Hokkaido in the 1890s. After the start of the Hokkaido Colonial Development Program in 1869, the Japanese government encouraged the settlement of Japanese migrants from mainland Japan to Hokkaido, and established an ordinance to issue certificates of land title in Hokkaido in 1877. It also started a land survey throughout Hokkaido (of course totally ignoring traditional relationship of Ainu people to the land) which was completed in the 1890s. A revenue office was established in Hokkaido in 1890. In the early years of colonization, land was exempted from tax, or taxed at a much lower rate, in Hokkaido than in mainland Japan.

Miyazawa Toshiyoshi, Kenpō Kōwa (Lectures on the Constitution), Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1967, p. 69.

Itō Masami, Kenpō Nyūmon (Introduction to the Constitution) [Supplemented 4th Edition], Tokyo: Yūhikaku, 2006, pp. 138-9.

Ebashi Takashi, “Senjū Minzoku no Kenri to Nihonkoku Kenpō” (Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and the Japanese Constitution). In, Higuchi Yōichi et al. (eds), Kenpōgaku no Tenbō (Prospects of Constitutional Studies), Tokyo: Yūhikaku, 1994, pp. 471-490.

Honda Katsuichi, Senjū Minzoku Ainu no Genzai (Indigenous Ainu People Now), Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, 1993, p. 220.

Uemura Hideaki and Fujioka Mieko, “Introduction. Nihon ni Okeru Datsushokuminchika no Ronri to Heiwagaku” (Theory of Decolonization in Japan and Peace Studies) in Japan Peace Studies Association (ed.), Heiwa Kenkyū: Datsushokuminchika no tame no Heiwagaku (Peace Research: Toward A Peace Studies for Decolonization) Tokyo: Waseda University Press, 2016, Volume 37, pp. 1-xx.

No Ainu participated in the “Utari Roundtable”. The logic behind their exclusion was that they possessed a “conflict of interests”. As for the “Expert’s Council on Ainu Policy”, Katō Tadashi (Chairman of the Ainu Association of Hokkaido) was the sole Ainu person serving as a Committee Member.

Satō Kōji, Nihonkoku Kenpō to Senjū Minzoku de aru Ainu no Hitobito (The Constitution of Japan and the Ainu, an Indigenous People) (Booklet Number 1), Sapporo: Hokkaido University Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, 2013, p. 6.

Tsunemoto Teruki, “Ainu Minzoku to ‘Nihongata’ Senjyūminzoku Seisaku” (The Ainu People and “Japanese” Indigenous Policy) in Gakujutsu no Dōkō (Academic Trends), Tokyo: Japan Science Support Foundation, 2011, Volume 9, pp. 79-82.

For example, Shinkawa Akira and Kanamaru Shinichi, editors of the only comprehensive magazine in “Okinawa” at the time, New Okinawa Literature, were made “Anti-Reversion Theory” a central feature of volumes 18 and 19 (1970-71) of the journal.

During the period of US rule, land was forcibly taken from Okinawan landowners for bases. Following a prolonged struggle in the 1950s, owners were paid rent for this land, but some owners refused to sign lease contracts, as a sign of their opposition to the presence of the military bases. After the reversion of Okinawa to Japan, the Japanese government introduced a series of measures forcibly extending these contracts, which were signed by local mayors as “proxies” for the anti-base landowners. If the mayors refused to sign (as three did in 1995-1996) the governor of the prefecture was required to provide a proxy signature on the leases. Governor Ōta’s refusal to provide this proxy signature resulted in a court case which he lost.

“Proxy Signature Lawsuit Prefecture’s Loss Confirmed”, Ryūkyū Shimpō, August 29, 1996. From this era, the movement to position the Ryūkyūs as “indigenous peoples” began to develop mainly within UN human rights institutions.

See also Gavan McCormack, “Japan’s Problematic Prefecture: Okinawa and the US-Japan Relationship”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, volume 14, issue 17, number 2, September 1, 2016; and Gavan McCormack and Sandi Aritza, “The Japanese State versus the People of Okinawa: Rolling Arrests and Prolonged and Punitive Detention”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, volume 15, issue 2, number 4, January 15, 2017.

The Okinawa Petition is a protest document from Okinawa Prefecture submitted to the Prime Minister of Japan in January, 2013, calling for the cessation of deployment of new military model Osprey aircraft as well as the closure and removal of the US Military Futenma Base. Unlike protests which had been submitted before that time, the Petition was a non-partisan document symbolically rising above ideology and including the signature of all of the 41 mayors and chairs of municipal assemblies in the Prefecture of Okinawa.

“Henoko Lawsuit Receives Supreme Court Ruling” (Editorial), Okinawa Times, 21 December, 2016. For further information on the Henoko struggle, see Hideki Yoshikawa (trans. Gavan McCormack), “U.S. Military Base Construction at Henoko-Oura Bay and the Okinawan Governor’s Strategy to Stop It”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, volume 16, issue 2, number 1, January 16, 2018.

Uemura Hideaki notes: I am indebted, and hereby express my gratitude to Ms. Takara Sachika of Okinawa University for providing me with information regarding the Okinawan situation.

The Ainu Cultural Promotion Act refrains from defining the rights of the Ainu people. Nonetheless, Article 1, which remains vitally important law in terms of recognition of the multicultural nature of Japan, reads as follows:

Article 1 To realize a society in which the ethnic pride of the Ainu people is respected and to contribute to the development of diverse cultures in our country, by the implementation of measures for the promotion of the Ainu traditions and culture from which Ainu individuals find their ethnic pride (hereafter referred to as “Ainu Traditions”), the spread of knowledge related to Ainu Traditions, and the education of the nation (hereafter referred to as “The Promotion of Ainu Culture”), in light of the situation Ainu Traditions are currently placed in (emphasis by authors).