Tripartite Talk by Saito Masami, Nogawa Motokazu, and Hayakawa Tadanori

Translation by Miho Matsugu

Introduction by Sven Saaler

In 2018, a number of events in Japan and Europe have reassessed the legacy of the 1968 student movement and related phenomena. Generally speaking, “1968”—still considered a symbol of a critique of capitalism, imperialism, and the Cold War world order—is usually associated with left-wing forces. Only in recent years has attention been paid to student organizations opposed to the 1968 left-wing movement. This facet of “1968” is particularly important in Japan, where student groups that rejected the left-wing agenda of organizations such as Zengakuren (Zen Nihon gakusei jichikai sō rengō, All-Japan League of Student Governments) have made political inroads, while the representatives of the left-wing student movement eventually failed to do so.

The right-wing student groups formed in the late 1960s evolved into a political organization that has recently received a good deal of attention in Japanese journalism and academia: Nippon Kaigi (The Japan Conference, hereafter NK). While this association was founded in 1997, the controversy surrounding Japanese history textbooks unfolding around the same time preoccupied many researchers. NK received broad public attention only in 2012, when Abe Shinzo became prime minister for a second time and presented a platform strongly influenced by the demands of NK, to which he has close ties.

The official aims of NK as stated on its website sound like a rather non-partisan appeal to national unity and universal humanism.

- We want to preserve traditional culture shaped by eternal (yūkyū) history and to stimulate a healthy national spirit.

- We aim to preserve the glory and sovereignty of the state and the construction of a wealthy and disciplined society in which every national finds his/her place.

- We aim at harmony between humankind and nature and the realization of a world characterized by mutual respect for culture. co-existence and prosperity.

However, in a society that still debates the historical legacy of ultra-nationalism and militarism, the advocacy of a “healthy national spirit” remains contentious. But beyond these broad goals, though closely linked to them, NK has been lobbying among lawmakers for controversial “reforms,” including a revamping of education as well as a “revision” of the 1947 Constitution. These NK proposals have stimulated scholarly interest, leading to a recent upsurge of studies on the organization. While the number of journal articles was already increasing, the years 2016 and 2017 saw the publication of more than a dozen books on the NK.

In this contribution, experts discuss these publications, summarizing the significance of NK influence on contemporary Japanese politics. A key issue is the far-reaching character of NK demands. Notwithstanding the organization’s innocuous-sounding objectives, the demands call for fundamental change in certain facets of Japanese society, including gender relations, the role of the family, and attitudes to war and peace, demographics, migration, even foreign relations.

While not all authors of this contribution agree on this point, many NK demands are deeply informed by 19th century or pre-war views. They directly challenge key reforms undertaken during the period of the Allied occupation of Japan (1945–52) and aim to “overcome” these reforms, as Prime Minister Abe puts it, and return to pre-war values. In terms of a revision of the Constitution, the most controversial among these topics, NK demands go far beyond an amendment of Article 9, the issue that has received the most media attention globally, to include a limitation on freedom of speech, and a constitutionally prescribed duty to value the “greater good” of society as well as a duty to care for one’s family. The latter has been widely seen as a step towards limiting the role of women and preventing women from succeeding in professional life. However, the authors of this contribution also point out the active participation of women in the NK, which even has a separate sub-organization and reduced membership rates to attract women to join. They also point out that apart from Yamaguchi Tomomi, none of the numerous books published in the last years really addresses the problem of NK’s views on women and gender issues.

Another important point raised in this piece is the strong influence of religious organizations on the NK. Religious organizations such as the followers of Taniguchi Masaharu, the founder of Seichō no ie, and others are closely related and to and strongly support NK. Politicians belonging to these religions have risen to powerful positions in the government, such as Inada Tomomi, a former Minister of Defense. However, notwithstanding these religious connections, the authors reject the characterization of NK as a cult.

Whether or not PM Abe will succeed with his pledge for constitutional revision in the next years, what is certain is that his agenda has been deeply shaped by the NK and the values and goals it promotes. (STS)

Dissecting the Spate of Books on Nippon Kaigi, the Rightwing Mass Movement that Threatens Japan’s Future: Nippon Kaigi is the Tip of the Iceberg

Discussion by Saito Masami, Nogawa Motokazu, and Hayakawa Tadanori

Translation by Miho Matsugu

The original Japanese version of the article is available in the Tosho Shinbun’s website.

Saito Masami, Nogawa Motokazu and Hayakawa Tadanori. “Nippon Kaigi-bon o Kiru!” [Dissecting the Spate of Books on Nippon Kaigi]. Tosho Shimbun, No. 2214, October 28, 2017. |

Nippon Kaigi [The Japan Conference] is the embodiment of a conservative mass movement that has been heavily influencing Japan’s politics. Numerous books were published on Nippon Kaigi in 2016 and 2017, and it is safe to say that the public is now aware of the group’s existence. Now that all these books on Nippon Kaigi have been published and the boom has finished its initial stage, Saito Masami, Nogawa Motokazu and Hayakawa Tadanori, who have been critically monitoring the activities of conservative groups, evaluate each book. They clarify what has happened “until now,” and will happen “from now,” in the study of Nippon Kaigi.

Hayakawa Tadanori (top left), Saito Masami (bottom left) and Nogawa Motokazu (right) in Tosho Shimbun, No. 2214, October 28, 2017. |

The Nippon Kaigi Book Boom, A Year On

Hayakawa Tadanori: In 2016 and 2017, about ten books and mooks (a publication that is a cross between a book and a magazine) were published on Nippon Kaigi. Nippon Kaigi is the embodiment of a conservative movementcreated in 1997 by the merger of “Nihon o Mamoru Kai” [Association to Protect Japan] which is made up of anti-communist rightwing religious groups including Jinja Honchō [the Associations of Shinto Shrines], and “Nihon o Mamoru Kokumin Kaigi” [National Conference to Protect Japan]. The latter was an organization of rightwing intellectuals andlocal veterans’ groups(called kyōyūkai). Nippon Kaigi attracted national attention when it emerged that many ministers in the Second Abe administration were members of Nippon Kaigi Kokkai Giin Kondankai [Nippon Kaigi’s Diet Members’ League], and when the group spearheaded a mass movement for constitutional revision in part by establishing “Utukushii Nippon no Kenpō o Tsukuru Kokumin no Kai” [National Association to Create a Beautiful Constitution for Japan].

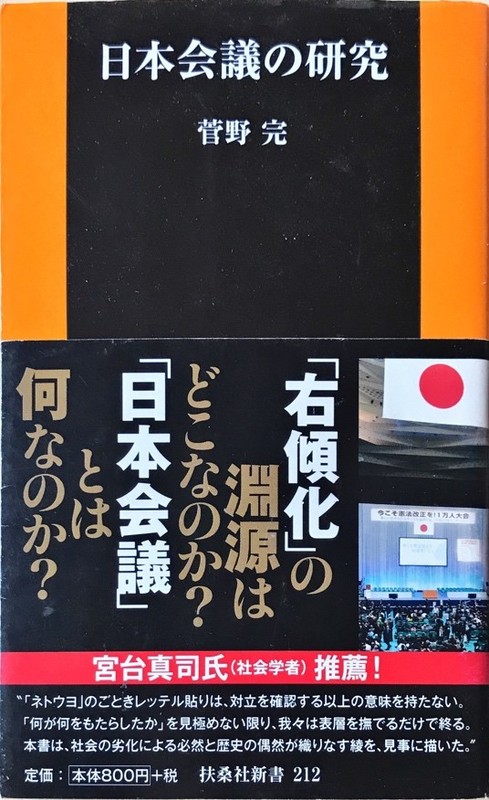

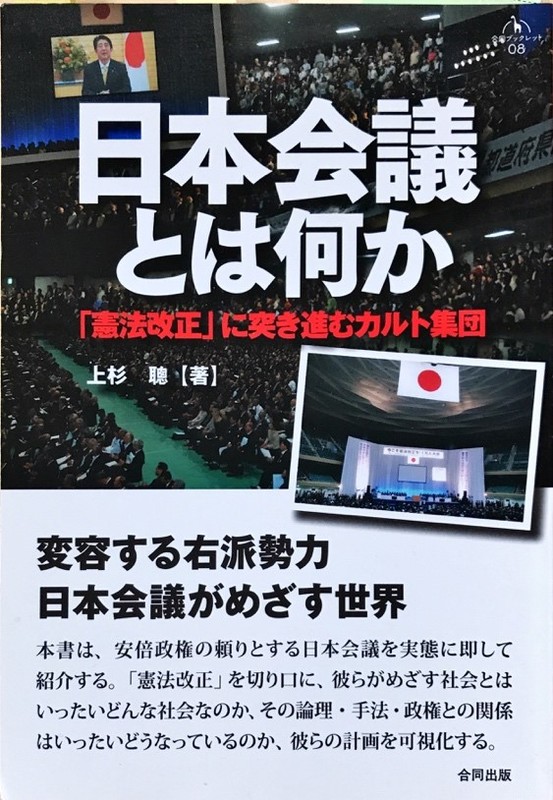

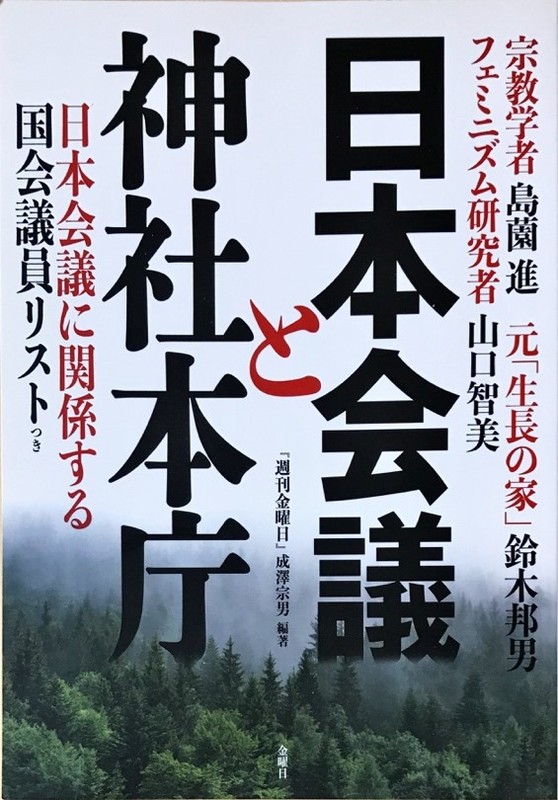

On September 5, 2016, Asahi Shimbun‘s evening edition carried a front-page story on the Nippon Kaigi boom in publishing, noting that Sugano Tamotsu’s Nippon Kaigi no Kenkyū [A Study of Nippon Kaigi] (Fusōsha 2016) had sold 150,000 copies, Uesugi Satoshi’s Nippon Kaigi towa Nanika: “Kenpō Kaisei” ni Tsukisusumu Karuto Shūdan [What is Nippon Kaigi? A Cult Group Rushing toward “Constitutional Revision”] (Gōdō shuppan 2016) sold 22,500 copies, and Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō [Nippon Kaigi and the Association of Shinto Shrines] (Kinyōbi, 2016) edited by Narusawa Muneo sold about 10,000 copies.

Sugano Tamotsu. Nippon Kaigi no Kenkyū [A Study of Nippon Kaigi] (Fusōsha 2016) |

Uesugi Satoshi. Nippon Kaigi towa Nanika: “Kenpō Kaisei” ni Tsukisusumu Karuto Shūdan [What is Nippon Kaigi? A Cult Group Rushing toward “Constitutional Revision”] (Gōdō shuppan 2016) |

Shūkan Kinyōbi, Narusawa Muneo (ed.). Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō [Nippon Kaigi and the Association of Shinto Shrines] (Kinyōbi, 2016) |

Nogawa Motokazu: Including other books, there must have been more than 330,000 volumes sold.

Hayakawa: As someone who publishes books in the unpopular field of humanities, that is a tremendous number. The eerie organization seemingly behind the Abe administration clearly has become a subject of popular interest. While the Abe administration is losing popularity, the move toward constitutional revision for the worse is accelerating under Kibō no Tō [the Party of Hope], led by Koike Yuriko, the Governor of Tokyo and a former vice Secretary-General of Nippon Kaigi’s Diet Members’ League.1 I believe that now is the time to take stock of the books that have been part of the Nippon Kaigi book boom.

Back in the 1970s, there were numerous books published on rightwing organizations. Works by political critic Yamakawa Akio2 and journalist Chamoto Shigemasa among others,3 triggered by Japanese-South Korean collusion and the Lockheed bribery scandal,disclosed how right wingers and former military personnel infiltrated politics. In the 1980s, excellent documents like Hayashi Masayuki’s Tennō o Aisuru Kodomotachi [Children who Love the Emperor] (Aoki shoten 1987) and Kokumin Gakkō no Asa ga Kuru [The Morning of National People’s School is Coming] (Tsuge shobō shinsha 1983) revealed how rightwing movements influenced highly controlled education.

From the 1990s, partly because of the prominence of the history textbook controversy, writers like Tawara Yoshifumi and Uesugi Satoshi published detailed reports on the rightwing network within “Atarashii Rekishi Kyōkasho o Tsukuru Kai” [The Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform]. Unfortunately, however, readers might have viewed these writings as merely about the history textbook controversy. It seems to me that their works did not boost social awareness of the overall structure of the right wing movement.

The start of the 2000s saw a conservative backlash against “male-female co-participation in planning” (danjo kyōdō sankaku—the Japanese government’s official English translation is “Gender Equality”),4 “gender free” (jendā furī),5 and “sex education” (sei kyōiku). Feminists fought against this backlash with a spate of books such as Jendā-Furī Seikyoiku Basshingu [Gender Free and Sex Education Bashing] (Otsuki shoten 2003), “Jendā” no Kiki o Koeru! [Overcome the Crisis of “Gender”!] (Seikyūsha 2006), and the most famous one, Bakkurasshu! [Backlash!] (Sōfūsha 2006).

In 2003, Iyashi no Nashonarizumu [Nationalism as Healing] by Oguma Eiji and Ueno Yoko (Keiō gijuku daigaku shuppankai), an account of people drawn to rightwing organizations like The Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform appeared. And in 2012, Shakai Undō no Tomadoi: Feminizumu no “Ushinawareta Jidai” to Kusanone Undō [Social Movements at a Crossroads: Feminism’s “Lost Years” vs. Grassroots Conservatism] (Keisō shobō 2012) by Yamaguchi Tomomi, Saito Masami, and Ogiue Chiki came out. Written from a feminist perspective, this book revealed how not only Nippon Kaigi but also the Unification Church of Japan (now the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification) have played a part in the grassroots conservative movement in Japan.

Saito Masami: Our book, Shakai Undō no Tomadoi, is an attempt to meet with and interview people who were on the conservative side during the 2000s when Nippon Kaigi and the Unification Church of Japan were leading thebashing of gender equality and sex education. We wanted to verify who they were, how they were organizing their networks, how they were acting individually, and what motivated their criticism. Although we were conducting research after the fact, we were able to trace the actions that conservatives were taking in their own fields. We pointed out that there was not only a “central control tower” giving orders, as has been understood, but that there were also various approaches to activism in each local area, using media, politicians and activists, and expanding their movement by cooperating with other regions. Still, our research was not able to reach Nippon Kaigi itself.

Nogawa: In 2008, Tawara Yoshifumi published a book titled “Tsukurukai” Bunretsu to Rekishi Gizō no Shinsō [The Split in “the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform” and the Depth of Historical Fabrication] (Kadensha) that detailed the split among proponents of textbook reform. But the book was not widely read. That’s why there are still many people who do not know that “the Society” broke up and that publishing companies such as Ikuhōsha and Jiyūsha are publishing right-leaning textbooks.

Hayakawa: Personally I think the Nippon Kaigi book boom was significant because it sparked broad interest in this rightwing group that was deeply embedded in the Abe administration’s efforts to revise the Constitution. There must be great numbers of people who have heard the name Nippon Kaigi, including those who may not have read books on the subject. That’s why many people were now able to look skeptically at the Moritomo Gakuen and Kake Educational Institution scandals, surfacing in February2010, and question their relationship to Nippon Kaigi.

Nogawa: It was especially clear when the Imperial Rescript on Education [Kyōiku Chokugo] problem occurred.6

Hayakawa: Most of the books on Nippon Kaigi point out that some of its core members were originally activists from Seichō-no-Ie [House of Growth]7 when it was run by the founder Taniguchi Masaharu. So the view that then Minister of Defense Inada Tomomi was “one of the Taniguchi Masaharu fundamentalists” made a splash when it came out that she had defended the private kindergarten Moritomo Gakuen’s use of the Imperial Script on Education in their curriculum. It was also interesting that Nippon Kaigi Osaka immediately announced that the chairman of the Moritomo school board, Kagoike Yasunori,8 was not one of their members.

Nogawa: Before the “Nippon Kaigi” book boom, there was some publicity around photos of politicians like prime minister Abe and Upper House member Yamatani Eriko9 with a former activist for Zaitokukai (or Zainichi Tokken o Yurusanai Shimin no Kai [Association of Citizens against the Special Privileges of the Zainichi Koreans])10, which has been distributing discriminatory propaganda. But the connections were not thoroughly investigated and seem to have been forgotten. It would have been different if the photos had come out after the boom.

Hayakawa: From 2014 to 2015, Zaitokukai was seen as the most troublesome group. But the Nippon Kaigi book boom made many people realize that there was a more established and larger movement behind the Abe administrations.

Saito: Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko’s exclusionist tendencies drew public attention when she included “opposition to the right to vote by foreigners in local elections11” as one plank in her Party of Hope’s political platform, and refused to send eulogies to an annual ceremony to commemorate Korean victims massacred at the time of the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 (doing so had been customary for Tokyo Governors). In his Nippon Kaigi no Zenbō: Shirarezaru Kyodai Soshiki no Jittai [The Complete Picture of Nippon Kaigi: The Unknown Reality of a Mammoth Organization] (Kadensha 2016), Mr. Tawara clearly explained Nippon Kaigi’s exclusionist stance, including its opposition to the proposal for the 2010 bill allowing non-Japanese residents to vote in local elections. His descriptions also anticipated the movement’s eventual political clout.

Tawara, Yoshifumi. Nippon Kaigi no Zenbō: Shirarezaru Kyodai Soshiki no Jittai [The Complete Picture of Nippon Kaigi: The Unknown Reality of a Mammoth Organization] (Kadensha 2016) |

Nogawa: The most impressive part of Mr. Tawara’s book is that it includes many names that are not mentioned in other books such as the members of Nippon Josei no Kai [the Japan Women’s Association]. Conversely, for first-time readers on the subject, it may be hard to understand.

Is Nippon Kaigi a Cult?

Hayakawa: While the boom in its entirety was very significant, each author takes a distinct approach and has a particular emphasis. As much as they overlap, their opinions are diverse.

Nogawa: Most of the books provide a common understanding of Nippon Kaigi’s historical origins. It is symbolic that the title of the series written for Asahi shimbun, which became the basis for Fujiu Akira’s Dokyumento Nippon Kaigi [Document Nippon Kaigi] (Chikuma shobō 2017), the latest among all the books in the boom, was “Nippon Kaigi o Tadotte” [Tracing the Path of Nippon Kaigi] (November 6-21, 2016). Authors don’t generally disagree about Nippon Kaigi’s historical background; I think they share a common understanding. For instance, they all say that a major moment in the establishment of Nippon Kaigi was the reign-name legalization movement.13 Although, in Nippon Kaigi no Kenkyū [A Study of Nippon Kaigi] (Fusōsha 2016),Mr. Sugano says “the movement for legislating the reign-name system was the beginning of everything” (40), he also says “the origin of Nippon Kaigi lay in its failure to pass the ‘Bill for the establishment of state support of Yasukuni Shrine’ [Yasukuni Jinja Kokka Goji Hōan]”14 (74). This inconsistency may stem from merely putting these serial essays together in a book, which may have backfired since each issue tends to have a catchy topic (originally published in a web media, Harbor Business Online).

I think what divides authors are their views on the source and extent of Nippon Kaigi’s influence and its source of funding. The Sugano book says that the Association of Shinto Shrines,15 which is often seen as Nippon Kaigi’s funder, is not so important. In chapter 5, titled “A Crowd of People” (Ichigun no Hitobito), he emphasizes the administrative skills of Nihon Seinen Kyōgikai (Nisseikyō) [Japan Youth Council],16 a group organized by former members of the right wing student movements, many of whom are former members of Seichō-no-Ie.

On the other hand, Yamazaki Masahiro in his Nippon Kaigi: Senzen Kaiki eno Jōnen [Nippon Kaigi: Passions to Return to Prewar Japan] (Shūeisha 2016) regards the Association of Shinto Shrines as crucial. Aoki Osamu’s Nippon Kaigi no Shōtai [Nippon Kaigi’s True Colors] (Heibonsha 2016) appears to be somewhere in between. Although Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō [Nippon Kaigi and Association of Shinto Shrines] edited by Narusawa Muneo has “the Association of Shinto Shrines” in its title, Narusawa’s own chapter is titled “Nippon Kaigi to Shūkyō Uyoku” [Nippon Kaigi and the Religious Rightwing], which looks not only at the association but also at other conservative religious groups.

I think that we should neither overestimate nor underestimate the Association of Shinto Shrines. Certainly it sounds like a giant organization when we hear that there are 80,000 shrines in Japan. But in reality there are only about 20,000 so-called shinto priests. In other words, most of the shrines do not have full-time priests. Therefore, it clearly is an exaggeration to say that 80,000 shrines are mobilized in the movement. On the other hand, wealthy shrines hold significant power when we include their accumulated assets, despite their limited numbers. These issues need more research.

Fujiu, Akira. Dokyumento Nippon Kaigi [Document Nippon Kaigi] (Chikuma shobō 2017) |

Yamazaki, Masahiro. Nippon Kaigi: Senzen Kaiki eno Jōnen [Nippon Kaigi: Passions to Return to Prewar Japan] (Shūeisha 2016) |

Aoki, Osamu. Nippon Kaigi no Shōtai [Nippon Kaigi’s True Colors] (Heibonsha 2016) |

Hayakawa: In terms of which is more influential, the former Seichō-no-Ie groups or the Association of Shinto Shrines, I would say both. But as someone who has seen a lot of their various activities, I think it is too simplistic to regard them exclusively as “right wing religious movements.” A certain number of ordinary people who have little to do with any religious group are also participating. And in some regions, local vocational schools or far-right conservative company presidents also take part.

Indeed, Nippon Kaigi is a conglomeration of a variety of new religious groups, some of whom are extremely reactionary. For example, OISCA International (The Organization for Industrial Spiritual and Cultural Advancement International), a non-profit foundation, originates in the former Ananai kyō. The school they ran was highly militaristic, emphasizing the principles of hakkō ichiu (The Eight Corners of the World under One Roof), a political slogan used to justify an international order for Asia with Imperial Japan at the top, and The Imperial Rescript on Education. Now OISCA is often portrayed as an international NGO working on developing farming villages and protecting the environment, but it used to be ardently anti-communist. As Tsukada Hotaka describes in his Shūkyō to Seiji no Tenketsuten [A Tipping point in Religion and Politics] (Kadensha 2015), each religious group has different characteristics and a different level of right wing politics, yet many of the books on “Nippon Kaigi” seem to focus only on the former Seichō-no-Ie members.

Saito: Some of their main targets are women and family. Abe Shinzo and Nippon Kaigi have taken various actions against women’s human rights including their opposition to allowing married couples to go by different surnames since the mid-1990s; their criticism of Gender Equality policy, sex education and the right of sexual self-determination since the early 2000s; and the promotion of family education under the 2006 “revision” of the Fundamental Law of Education.17 While the Abe administration currently has a policy called “Women’s Active Participation” (josei katsuyaku), Abe Shinzo, as the chairperson of the Liberal Democratic Party’s Project Team to Investigate Extreme Sex Education and Gender Free Education, has a history of running counter to the Gender Equality policy by spreading groundless rumors about co-ed cavalry battles and men and women changing clothes in the same room. However, these books do not mention issues of women and family other than their opposition to separate surnames for married couples. Mr. Tawara’s book is an exception, giving details about the move toward constitutional revision like “Joshi no Atsumaru Kenpō Oshaberi Kafe” [The Cafe where Girls Get Together to Chat About the Constitution18. On the contrary, although Mr. Sugano talks about the issues of gender, there are some problems in his approach.

Nogawa: I remember thinking that Mr. Sugano does not really understand gender issues, when I read what he wrote about the two Supreme Court rulings on allowing separate surnames for a married couple. One ruling, he said, found it “unconstitutional” to forbid remarriage for a certain period. The other said it was “constitutional” to require a single surname for a married couple. He writes that these rulings represent a “very clear contrast.” Actually the court only declared “unconstitutional” an extended remarriage ban of more than one hundred days, and did not rule against the idea as a whole. It was not a response to the fundamental question asked by the plaintiff, of whether it is against the principle of equality under law when only women are not allowed to remarry given the advances of reproductive technology. It was nothing like the “clear contrast” that he claims to find.

Saito: Yet Mr. Sugano is saying on twitter and other social media that Nippon Kaigi is a “shut-up-women-and-kids” movement.

Hayakawa: Does it really “shut up women and kids”?

Saito: Not at all. Nippon Kaigi is certainly a male-centered organization, but it created Nippon josei no kai [Japan Women’s Association] and it does place women in positions as needed, like making Sakurai Yoshiko19 a co-representative for their “Utsukushii Nippon no Kenpō o Tsukuru Kokumin no Kai” [National Citizens’ Association to Create a Beautiful Constitution for Japan]. They do not openly tell women to shut up or look down on them, although they do emphasize the division of labor by gender and the value of family. In fact, plenty of women actively participate in the movement.

Nogawa: And take Mr. Yamazaki’s idea that Nippon Kaigi is all about a “return to prewar Japan.” It is true that right wing movements tend to evoke the image of the return to prewar Japan, just as the Imperial Rescript on Education became the focus in the Moritomo Gakuen Incident. But if we frame everything in that lens, we end up overlooking many things. For instance, as only Mr. Tawara’s book points out, recent educational reforms in Japan are modeled on those by Margaret Thatcher’s administration. Kabashima Yuzo, the president of the Japan Youth Council and Executive Secretary of Nippon Kaigi, and Nakanishi Terumasa, Professor Emeritus of Kyoto University, made a study trip to England with politicians including Shimomura Hakubun and Eto Seiichi and published Sacchā Kaikaku ni Manabu Kyōiku Seijōka eno Michi [The Path to Normalization of Education Learned from Thatcher’s Educational Reforms] (PHP kenkyūsho 2005). In other words, while some of the family policies and historical view of Nippon Kaigi are specific to Japan, new-conservatism gives those policies more of a global stage. I think the generalization of Nippon Kaigi as a “return to prewar Japan” may lead us to miss that point.

Hayakawa: In the case of Mr. Yamazaki’s book, I notice the way he finds expressions in Kokutai no Hongi [The Essence of the National Polity] (ed. Ministry of Education, 1937) that are similar to Nippon Kaigi’s statements and insists they are identical. To be sure, there are commonalities between prewar nationalist fundamentalism and contemporary right wing movements. But Nippon Kaigi is not making “the return to prewar Japan” its goal. Finding simplistic analogies in prewar Japan is easy to do, and I am as guilty of it as the next man, but I am afraid that it gets in the way of understanding why, at this moment in history, they are embracing a movement based on the prewar view of the family state.

Saito: It is illogical to say that Nippon Kaigi’s ideology is a “return to prewar Japan” just because its arguments are similar to those of The Essence of the National Polity during the war, which has nothing to do with Nippon Kaigi’s activities.

Nogawa: A book published this past spring, Kore ga Warera no Kenpō Kaisei Teian da [This is Our Proposal for Constitutional Revision] by Ito Tetsuo, Okada Kunihiro and Kosaka Minoru20 (Nihon seisaku kenkyū sentā 2017), objects to the criticism that Nippon Kaigi wants “to revive the ie system,” thepatriarchal family legislative system of imperial Japan. Indeed, ideologues of Nippon Kaigi themselves argue that “postwar GHQ destroyed our ie system,” so in some sense they are bringing this criticism on themselves. They are not trying to revive the rights of the household head as they were before the end of the war, but rather aim at the “restoration of family” in a form that fits the present time.

Saito: To demonize them as a “cult,” “a crowd of people,” or an “inner circle” is problematic too. It’s a problem to try to consider Nippon Kaigi as heresy, claiming that they are a pack of evildoers.

Nogawa: The subtitle of Mr. Uesugi’s book refers to Nippon Kaigi as a “Cult Group.” The book defines “cult” as being “ignorant of the world, or not understanding the reality of society,” and to have a “tendency not to think independently.”

Saito: I think it’s very bad to use the word “cult,” especially in Japan, where the image of religion as scary or eerie tends to be strong. I feel that the book is trying to take advantage of this image.

Nogawa: The use of the word “cult” as I just mentioned may promote discrimination against religion, since, in Japan, it became known to the general public through the incidents caused by The Unification Church of Japan and Aum Shinrikyō. When I think about that kind of danger, Mr. Uesugi’s definition is excessively arbitrary. In the sociology of religion since the 1970s, the term “cult” usually refers to “a new religion that has a tense relationship with society (Shūkyōgaku Jiten [Religious Studies Encyclopedia] ed. Hoshino Hideki et. al, Maruzen shuppan, 2010). For example, with The Unification Church’s inspiration business fraud and Aum Shinrikyō’s terrorist sarin attack on the Tokyo subway, we can say, for the time being, that calling these institutions a cult follows this academic use of the word. I think, however, it is necessary to question whether the word is being used simply to designate a minority, as seen by the majority.

But to answer the question of whether we can call Nippon Kaigi or religious groups affiliated with Nippon Kaigi a cult, we have to look at the current state of Japanese society. For example, I am not sure if our society has such a tense relationship with the values of the Japan Youth Council that we would call them a cult.

Hayakawa: I see. It is not whether they are a cult or not, but whether we are able to separate ourselves from them as a cult.

Nogawa: In order to call them a cult, Japanese society must have had established values that are clearly disengaged from their values. But can we say that we have that kind of tense relationship with them? The issue of Moritomo Gakuen, for instance, had been well known among some people for a long time. The reason it became a topic for daytime tabloid TV shows, however, is because they were caught in a money scandal. Whatever we say, it was Japanese society who had neglected the kindergarten. That’s why I want to ask ourselves if we have the qualifications to call them a cult.

Nippon Kaigi, the History Wars, and Anti-Feminism

Hayakawa: You have both been looking at right wing conservative movements influenced by Nippon Kaigi. Is there anything that particularly concerns you?

Saito: For Nippon Kaigi, family education is very important, but these books say little about this. In his book, Mr. Tawara, who is knowledgeable about education, has the most detailed discussion of Nippon Kaigi’s emphasis on family. But school education was still his main focus. Oyagaku [Parental Education],21 advocated by Takahashi Shiro22 who has a very close relationship with Nippon Kaigi, regards the roots of various problems for children as “residing in problems at home,” and particularly those involving their parents’ “lack of effort to create affection.” Saying that “how parents engage is important,” oyagaku puts particular emphasis on family education (ed. Takahashi Shiro, Zoku Oyagaku no Susume [Encouragement of Parental Studies Part 2], Morarojī kenkyūsho, 2006).

Nogawa: Mr. Tawara, too, points out that the revision of the Fundamental Law of Education is modeled on the United Kingdom. But he cannot go further than that because, I think, he has not delved more deeply into the problem of family.

Hayakawa: Mr. Tawara and his group Kodomo to kyōkasho zenkoku netto 21 [Children and Textbooks Network Japan 21] focused on the changing view of family during the 1998-1999 revisions of home economics textbooks for elementary, middle and high schools (Tsuruta Atsuko, Kateika ga Nerawareteiru [Home Economics is Targeted] Asahi shimbunsha, 2004). That problem is resurfacing now.

Nogawa: In fact, right wing intellectuals who are very close to Nippon Kaigi, such as Yagi Hidetsugu 23and Takahashi Shiro, still now actively bring up home economics textbooks as their issue.

Saito: Takahashi Shiro has been reappointed twice as a member of the expert committee for the Conference for Gender Equality of the Cabinet Office under the Abe administration. He has also entered the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Yagi Hidetsugu, too, is a member of the subcommittee of the Civil Code in Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice and of Kyōiku Saisei Jikkō Kaigi [Education Rebuilding Implementation Council] in the Cabinet Secretariat. Both Takahashi and Yagi are taking active roles in the center of the government.

Nogawa: You mean, methodologically speaking, their feminist point of view is very weak.

Saito: Yes. That home and family do not enter the minds of the authors of the “Nippon Kaigi” books means that they do not understand the true nature of Nippon Kaigi. My fear reaches that level.

Almost all the authors of the “Nippon Kaigi” books are men. Nippon Kaigi has been tackling gender, sexuality and family as issues that are important for their theory of the state. But almost none of these books address what Nippon Kaigi has done on these themes. Only Ms. Yamaguchi (Tomomi), in Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō, discusses gender and sexuality, arguing that Nippon Kaigi has deployed the movement against the separate surnames for married couples in order to stop what they see as the breakdown of the family. She clearly writes that one of Nippon Kaigi’s targets is to weaken Article 24 of the Constitution.

Nogawa: By the way, the Sugano book says that Nippon Kaigi’s most likely target for constitutional revision is not Article 9 but Article 24 and the Emergency Situation Article. Ms. Saito and I both support 24 jō Kaesasenai Campaign [The Campaign to Oppose LDP and Rightist Revision of Article 24] and yield to no one in drawing public attention to it. Still, Sugano is wrong. Nippon Kaigi’s true target remains Article 9. He uses this kind of contrarian claim in order to give his argument a semblance of originality. For example, he points out that Sakurai Yoshiko, one of the co-representatives of the National Citizens’ Association to Create a Beautiful Constitution for Japan, mentioned only two concrete issues at a conference hosted by the association on November 10, 2015: the “Emergency Situation Article” and “family.” Sugano writes that this shows “their posture is to prioritize these two over Article 9.” But if you listen to Ms. Sakurai’s speech, even though “Article 9” as a word does not appear, it is obvious that “Article 9 constitutional revision” (kyūjō kaiken) is uppermost in her mind. Also, other than those two issues, she concretely mentioned the preamble of the Constitution. I’d like to touch later on this kind of arbitrariness in interpreting materials and testimony.

Also, while they focus on Seichō-no-Ie, almost none of the authors look at Yūsei hogohō kaisei undō24 (the movement to revise the Eugenic Protection Law). Actually this is one of the themes that Seichō-no-Ie was obsessed with.

Saito: Recently there are signs of a dangerous turn of events. This July (2017), in Kaga City, Ishikawa Prefecture, the Mayor Miyamoto Riku, one of the founders of Nippon Kaigi Chihō Giin Renmei [the Nippon Kaigi Local Assembly Members’ League], succeeded in passing an ordinance called “Onaka no Akachan o Taisetsu ni suru Kagashi Seimei Sonchō no Hi Jōrei” [OrdinanceDesignating A Day for Caring for Babies in Their Mothers’ Tummies]. The move came in cooperation with the headquarters of “Seimei Sonchō Center” [Pro-Life Center] in Tokyo. The Pro-Life Center claims “human rights for the fetus” and hosts lectures to raise awareness by creating akachan posuto (side haven boxes for new mothers to relinquish their babies without penalty)25 criticizing the current Maternal Body Protection Law (Botai Hogo Hō) under which economic reasons can justify legal abortion.

Nogawa: Regardless of whether the ordinance is a result of Nippon Kaigi’s organizational activities, it is ideologically consistent with it.

Saito: Yes, it is. The word “pro-life” (seimei sonchō) is being used to deny the right to self-determination for women as part of women’s reproductive health and rights. We have to keep our eye on this.26

Hayakawa: “Pro-life for the fetus” was a key phrase that often appeared in efforts in the 1980s by Seichō-no-Ie to revise the Eugenic Protection Law.

Saito: Seichō-no-Ie had tried to revise the Eugenic Protection Law in the 1970s, but failed because of opposition from some members of the Liberal Democratic Party, the Japan Medical Association, and the women’s liberation movement.27 In 1982, Murakami Masakuni,28 a member of the Upper House and affiliated with Seichō-no-Ie, claimed that “fetuses are human” and used calls for “pro-life for the fetus” to try to revise the law. Again opposition from women’s groups short-circuited this attempt, but he was very active in doing things like using Mother Teresa’s words.

Nogawa: But many of the authors view Murakami in a favorable light because he is their source of information.

Saito: This is why I think we are at a crisis point.

Nogawa: Takahashi Shiro, a member of Nippon Kaigi, is still active in the anti-reproductive rights movement. He and some others have given talks in recent years at rallies held by an organization that advocates the “rights of the fetus.” Relating to the topic of the return to prewar Japan that we just discussed, the current push to regulate reproductive rights is not a simple repetition of efforts to debase the Eugenic Protection Law. We should look at it as a movement linked to social concern over the declining birth rate.

Saito: They are using it cleverly. By talking about the policy in terms of the declining birth rate and the crisis of a decreasing population, it makes us hard to see that their true goal is to deny a woman’s right to decide whether she will give birth or not.

Nogawa: The rhetoric of “a state of emergency” (kinkyū jitai) is also often used. This pulls people into a conservative backlash. If someone says “That’s dangerous!,” your response would more likely be “Oh my god!”

Hayakawa: You mean that these books on Nippon Kaigi rarely take up these right wing mass movements that have become enmeshed in our everyday lives.

Saito: I wonder if the authors of the books are not so interested in the problems of everyday life.

Nogawa: Exactly. Considering how much they emphasize the “grass roots” nature of the Nippon Kaigi’s movement, I feel that they ignore the activities of those living outside of Tokyo. This may be also related to the fact that most of the authors of the Nippon Kaigi books, including the media, live in Tokyo. In this sense, the greatest contribution of the Uesugi book is chapter five “Ikuhōsha wa Osaka de Donoyōnishite Tairyōsaitaku o Jitsugen Shitaka?” [How did Ikuhōsha Publishers. Make Possible the Massive Adoption of Their Textbooks in Osaka?], which describes the activities of Ikuhōsha29 in detail. This chapter is very worthwhile.

Saito: It gets into a structural analysis of the movement.

Nogawa: The fifth chapter is very useful for thinking about what exactly is happening in other regions. It mentions a company called Fuji Housing (Fuji Jūtaku).30 There are many CEOs and presidents who support this kind of movement all over Japan. In the context of Mr. Hayakawa’s question about whether to characterize Nippon Kaigi as a religious right wing movement, I think the presence of business people in local areas is often overlooked. At a rally by Nippon Kaigi Osaka on Constitution Memorial Day this year, a consulting company was involved in organizing the event and some of their employees were participants in the symposium.

I see only few books that talk about what Nippon Kaigi is really doing now. The Fujiu book, the most recently published, also focuses only on the historical origin.

Saito: I wonder why he does that when others have already done so.

Nogawa: Mr. Fujiu has been researching Nippon Kaigi for a long time, so I read his treatment of Nippon Kaigi’s historical origin as quite reliable. But what is happening now? Pardon me for my bias for wanting to talk about my own interests, but for example, we are at the height of the talk of “history wars” (rekishisen). Right wingers use the term “history wars” in reference to claims about “comfort women” and the “Nanjing Massacre” as false accusations in order to appeal to supporters both domestically and internationally.

Hayakawa: Speaking of the “history wars,” it was revealed in 2015 that LDP Upper House member Inoguchi Kuniko had sent out copies of the book History Wars: Japan-False Indictment of the Century, a shortened bilingual version of Rekishisen: Asahi Shimbun ga Sekai ni Maita ‘Ianfu’ no Uso o Utsu, published by Sankei shuppan, to numerous scholars of Japan in the United States.31

Nogawa: The Sugano book says that Takahashi Shiro wrote the letter opposing the inclusion of the Nanjing Massacre in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register sent by the Japanese government to UNESCO.32 The Yamazaki book also introduced Nippon Kaigi arguments denying both the Nanjing Massacre and the comfort women problem.

Hayakawa: I recently heard that a U.S.-based organization affiliated with the self-help group Rinri kenkyūsho [RINRI Institute of Ethics], which constitutes a part of Nippon Kaigi, is actively pressing a historical revisionist movement in New York and elsewhere. They are waging the “history wars,” including opposing the building of a “Statue of Peace” (statue commemorating military comfort women) and mobilizing people in the United States behind their movement. Nippon Kaigi is an umbrella organization for such movements. I believe this is the sketch that we have to have in mind when we talk about the “complete picture.”

Nogawa: If I may defend these authors a little, it might be hard for a single author to cover so much. The only authors who have been able to meet Nippon Kaigi members are Mr. Aoki and Mr. Fujiu. Mr. Sugano talked only to former members of Nippon Kaigi, who may have been able to talk candidly, but because they have left group their information might be wrong or be mixed with their personal antagonistic bias. We have to be careful about that.

Saito: Mr. Aoki and Mr. Fujiu both write about the difficulty of interviewing members, many of whom refused to talk with them. I admire and appreciate that these two journalists conducted interviews despite such difficulty. With increasing attention to Mr. Sugano’s articles on the Internet, I think that interviewing people in Nippon Kaigi has become harder. I myself was refused when I asked for the schedule of one of their constitutional revision campaign trucks. They said “we are only allowed to tell our board members.” I feel keenly the difficulty of research.

Further Critique of Ideological and Cultural Activism

Hayakawa: The concept of family, including the multigenerational family advocated by people like Momochi Akira33 (a member of Nippon Kaigi’s strategic committee), emphasizes “family bonding” as an ideal. They call for “caring for elders within the family.” Moreover, their Japanese family ideal provides justification to cut welfare. Takahashi Shiro and Yagi Hidetsugu, too, say, “This is an advantage of the Japanese welfare society.” The origin of this ideology is the Ohira Masayoshi administration’s “Policy for Perfecting Family Foundations,” which began in 1979. This is the forerunner of neoliberalism in Japan, much like Thatcherism or Reaganomics. It may appear as if Nippon Kaigi were praising the restoration of the prewar family. Yet what they propose as policies are in fact those of neoliberalism. If we frame everything as “misogyny” or “the return to prewar,” I think it makes it hard to see the discrepancy between the ideals they hold up and the reality of their actions, which will end up misleading readers.

Nogawa: The only book that mentions the name of Kato Akihiko, the professor at Meiji University who advocates multigenerational family residence, is Mr. Tawara’s. I give him credit for this.

Saito: We now have a pretty good sense of Nippon Kaigi’s background and the overall picture. Now we need micro-level fieldwork and investigative reporting on different themes and areas.

Hayakawa: I agree. For instance, the multi-generational household we discussed ended up being incorporated into government policy, through the tax incentive for multigenerational households (2015) passed during the second Abe administration. But if we conclude that there’s never anything wrong with a tax cut, we miss the family view that drives it.

Saito: The tax incentive applies even to those who are not living with their parents and grandparents. Still, they use the word “multi-generational household” that seems to favor a family of parents, their children and their grandchildren.

Hayakawa: After all, it became a system that gives you a tax advantage. Bottom line, as long as a construction project includes additions to accommodate another household, a second kitchen, bath tub, toilet, or entrance, you get favorable tax treatment. This is a prime example of the gap between their ideals and reality. Of course this is mainly a result of resistance on the part of the Ministry of Land, Information, Transport and Tourism and some members of the LDP to a taxation system that rewards certain life choices, but it would be interesting to follow the process at the micro level, starting from the proposal by Nippon Kaigi to when the policy was put into effect.

Nogawa: In any case, each book connects Nippon Kaigi with the Abe administration. Yet the problems each author finds in the Abe administration determine the problems that the author sees in Nippon Kaigi.

Hayakawa: Mr. Sugano writes, “Compared with any other prime ministers and LDP presidents, Abe is easily compromised and easily influenced by rightwing organizations’ old trick of ‘jōbu kōsaku’,” (sending members into positions in government or a political party thereby influencing their policy agenda and ideology) because the foundations of the administration are weak. This argument emphasizes the influence of what he calls “a crowd of people” within Nippon Kaigi, especially Ito Tetsuo, as “a promoter of Abe Shinzo.” The book reads as if Abe were manipulated by “a crowd of people.”

Nogawa: The Aoki book does that too. The Uesugi book says that Abe, influenced by his grandfather Kishi Nobusuke, had called for the revision of Article 9 since his college days. His diagnosis is that Abe was drawn to such ideology since his youth. Both Mr. Aoki and Mr. Sugano see Abe as an empty vessel. Their opinion is divided about what is all-important, however: that is, whether Abe Shinzo has an ideological affinity for Nippon Kaigi or not.

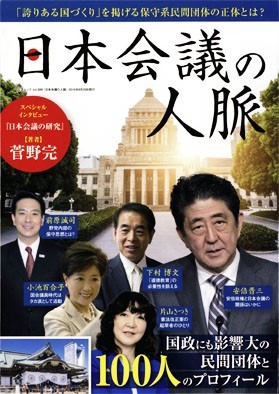

Hayakawa: On that, Nippon Kaigi no Jinmyaku [The Human Network of Nippon Kaigi] by Sansai bukkusu gives a detailed introduction into the brains behind both the administration and Nippon Kaigi’s think tank. It’s a good book, but unfortunately positive for the administration (laugh).

Focusing only on Nippon Kaigi could lead us to overlook other right wing movements that are gradually penetrating Japanese society, such as Nihon Seinen Kaigisho (Junior Chamber International Japan, or JC), Morarojī (The Institute of Moralogy), Rinri kenkyûsho (RINRI Institute of Ethics), the Clean-the-toilet-with-bare-hands-movement by Nihon o Utsukushikusuru Kai (the Council to Make Japan Beautiful) and other nationalistic business groups. Just this summer JC held its annual summer conference in Yokohama. I heard that there were many poster presentations on “the history wars.” JC’s organizational capacity and financial muscle should not be underestimated. It has already gotten deeply into education through programs like Ryōdo Ryōkai Ishiki Jōsei puroguramu [On and Offshore Territorial Consciousness-Raising Program], Tokuiku Zemināru [Moral Education Seminar], and Anzen Hoshō Kyōiku puroguramu [National Security Education Program].

Sansai bukkusu (ed.). 2016. Nippon Kaigi no Jinmyaku [The Human Network of Nippon Kaigi]. Sansai mook, vol. 899. Tokyo: Sansai bukkusu. |

Nogawa: Many important members of Nippon Kaigi do not appear in these books.

Saito: For example, among the forgotten are Tashimo Masaaki, a pediatrician and executive secretary of the Hokkaido branch of Nippon Kaigi, and Okamoto Akiko, an activist journalist.34 Ms. Okamoto was long a very active member of Nippon Kaigi, writing for journals like Seiron and speaking as a housewife. She was deeply involved in Nippon Kaigi’s movement to prevent married couples from having separate surnames, and the backlash against the Gender Equality Policy. Ms. Okamoto accused the Japanese government of sending only leftists to the United Nations. In order to watch developments on women’s rights and family issues at the UN, she founded Kazoku no Kizuna o Mamoru kai or FAVS [Family Value Society] and sent people to the hearings by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and the Committee on the Rights of the Child. Yamamoto Yumiko of Nadeshiko akushon (Nadeshiko Action, Japanese Women for Justice and Peace), an organization formed to deny the “comfort” women problem, and Ganaha Masako of Ryūkyū Shinpō Okinawa Taimusu o Tadasu Kenmin Kokumin no Kai [Association for the Inquiry of Ryūkyū Shimpō and Okinawa Times by the People of Okinawa and Japan], an anchor woman for the Okinawa branch of Channel Sakura, carry on Ms. Okamoto’s legacy.35

Nogawa: This is important. In addition, Ms. Okamoto wrote in the May 2012 issue of Seiron that Japanese children were bullied in the U.S. because of the “Comfort Woman Monument,” and pioneered criticism of “Comfort Woman Monuments” in the United States and other countries.

Saito: I met a member of Nippon Kaigi who said “Mr. Tashimo is important for me.” His house had many books written by Mr. Tashimo. Particularly important to him were a series of articles titled “Seminar to support raising kids who say I love Japan, Thank you mother” that Tashimo wrote in Nippon Kaigi’s official publication, Nippon no ibuki [Japan’s Breath of Energy]. “Mr. Tashimo’s articles are the most important,” he told me. “Everyone in our house is reading them.” The series was written for mothers to learn about raising children.

Nogawa: Mr. Tashimo’s main theme is a critique of the “critique of the myth of the first three years.” He says it is not a myth.

Hayakawa: If we only look at how Nippon Kaigi advocates “constitutional revision,” we will not pay attention to ideologues like Mr. Tashimo who focus on child rearing and family.

Nogawa: The only works of Ito Tetsuo that Mr. Aoki includes inches bibliography are Ito’s books on the constitution and the Imperial Rescript of Education. Based on this, we can see where Mr. Aoki puts his emphasis.

Saito: Nippon Kaigi considers important not only matters of state such as constitutional revision and national security but also culture. In terms of legislating the reign-name system, for instance, they know people are easily drawn in through everyday life, through events like “the Day of Meiji” and “the Day of Showa.”36 I also heard that some are questioning the way Motoya Toshio (CEO of APA group37) and his followers focus on hardcore politics and suggest, instead, a softer way through culture.

Nogawa: Looking only at hard-headed people keeps us from seeing how so-called ordinary people are participating in the movement.

Also in his book, Mr. Sugano interviewed an adjunct lecturer at Doshisha University who had been recruited by Japan Youth Council, but in this case the recruitment failed. While he writes that Nisseikyō skillfully persuade people to join the group, Mr. Sugano says young members are all the children and grandchildren of members. I see this kind of contradiction everywhere in his book. But scholars seem to often refer to this book since it was the first and it sold well.

Saito: Sugano writes that Nihon Seisaku Kenkyū Sentā or Japan Policy Institute focuses on four main issues: “historical recognition,” “opposition to separate surnames for married couples,” “military comfort women,” and anti-“gender free,” referring to the May 2004 issue of Asu eno sentaku [Choice for tomorrow], the institute’s journal. He writes that these are also the “main themes” for the Abe administration. A scholar referred to this part and wrote as if these four themes were still the Japan Policy Institute’s.38 The Sugano book is problematic because it introduces random documents convenient for his argument without considering the context.

Nogawa: Mr. Sugano also writes about Takahashi Shiro’s study abroad in the United States largely based on speculation. As supporting evidence, he says that Takahashi had written almost no “articles on education.” I wonder how he researched this claim. Until the mid-1980s, Takahashi Shiro wrote many articles on educational reform under the occupation. Sengo Kyōikushi Kenkyū Sentā (The Research Center for Postwar Educational History of Japan) at Meisei University was established using materials Takahashi collected in the United States. The author uses his unfair evaluation of Takahashi’s work to speculate about his motivation to study in the U.S. Because it is a best-selling book, I’d like to make this point clear.

Saito: I met someone, a right winger, who told me that he was angry because Mr. Sugano wrote about him as if Nippon Kaigi and Ito Tetsuo manipulated him, without even interviewing him. He said he complained to Fusōsha39, the publisher of the book.

Hayakawa: The book’s climax points to Ando Iwao40 as “a man who is standing at the origin of the swing to conservativism.” We can see that he wanted to identify the same kind of “final boss” character found in video games by digging up the human network of the former Seichō-no-Ie in Nippon Kaigi. But this is surprising when we look at the mainstream scholarship of the postwar right wing movements. Also, I thought the ending in which he says “We are still living in the extension of the violence in front of Nagasaki University’s main gate” is a quite stunning characterization.

Saito: It must be so upsetting if you were labeled that on the basis of simple speculation.

Hayakawa: Although the Sugano book was a best-seller, I have doubts about relying exclusively on this book, especially in the academic field. I hope scholars will look at not only the Nippon Kaigi books but also other books on right wing movements.

Nogawa: At least I want them to read more than two books so that they have a basis for comparison.

Saito: But in reality I bet most people only read the Sugano book.

Nogawa: Basically most of the authors are either scholars who are interested in the textbook problem or journalists. This topic may be too new and close to tackle, but in the future, political scientists will have to analyze the actual policy-making process and find out how Nippon Kaigi became involved. After all, it looks like we just took the first step in that vein with these smaller scale book forms such as shinsho, mook, and booklets. Scholars and journalists should build on these thin volumes and delve into the topic of Nippon Kaigi more deeply.

Hayakawa: I think many people have been able to grasp the contours of Nippon Kaigi for the time being. Now we need a critique of the ideology and thought that penetrates the Nippon Kaigi movement.

Saito: We have to include their cultural activities in addition to critiquing thought.

Nogawa: And it’s also important to know what kind of society they want to create. Aside from whether I agree with him, in this sense, I can understand the aim of Mr. Yamazaki’s “return to prewar” criticism.

Saito: We need to examine how conservative politicians, from the Abe administration’s cabinet down, turn the Nippon Kaigi ideology into policies and laws. At the same time, those who are engaged in religious groups’ activities that are tied to grassroots movements may not be aware that they are participating in the Nippon Kaigi movement. I think it’s important to look carefully at what Nippon Kaigi is doing every day.

Hayakawa: We’ve got enough books dissecting Nippon Kaigi as a cult. Nippon Kaigi is “the tip of the iceberg” and under the surface, it encompasses various movements, seminars, lectures, and patriotic businesses. I believe we are reaching a phase where we must turn our focus to concrete right wing movements that are connected with our daily life.

Related articles

- Hayakawa, Tadanori. Translation by Joseph Essertier. “The Story of the Nation: ‘Japan Is Great,’”

- Jeff Kingston, “Nationalism in the Abe Era”

- Adam Lebowitz and Tawara Yoshifumi. “The Hearts of Children: Morality, Patriotism, and the New Curricular Guidelines.”

- David McNeill, “Nippon Kaigi and the Radical Conservative Project to Take Back Japan.”

- Sachie Mizohata, “Nippon Kaigi: Empire, Contradiction, and Japan’s Future.”

- Mark R. Mullins, “Neonationalism, Religion, and Patriotic Education in Post-disaster Japan.”

- Nakano Koichi, “Contemporary Political Dynamics of Japanese Nationalism.”

- Nogawa, Motokazu and Nishino, Yumiko. Translation by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen. “The Japanese State’s New Assault on the Victims of Wartime Sexual Slavery.”

- Lawrence Repeta, “Japan’s Democracy at Risk – The LDP’s Ten Most Dangerous Proposals for Constitutional Change“

- Sven Saaler, “Nationalism and History in Contemporary Japan” https://apjjf.org/2016/20/Saaler.html

- “Nationalism and History in Comporary Japan.”

- Sasagase Yuji, Hayashi Keita and Sato Kei. “Japan’s Largest Rightwing Organization: An Introduction to Nippon Kaigi.”

- Akiko Takenaka, “Japanese Memories of the Asia-Pacific War: Analyzing the Revisionist Turn Post-1995.”

- Tawara Yoshifumi. “The Abe Government and the Screening of Japanese Junior High School Textbooks 2014.”

- Tawara Yoshifumi and Tomomi Yamaguchi, “What is the Aim of Nippon Kaigi, the Ultra-Right Organization that Suports Japan’s Abe Administration?”

References

Aoki, Osamu. 2016. Nippon Kaigi no Shōtai [Nippon Kaigi’s True Colors], Tokyo: Heibonsha.

Beckford, James A. and Demerath III, N. J. (eds). 2007. The SAGE Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and Singapore: SAGE Publications.

Dower, John W. 1999. Embracing Defeat: Japan in The Wake of World War II. New York and London: W. W. Norton and Company/ The New Press.

Fujiu. Akira. 2017. Dokyumento Nippon Kaigi [Document Nippon Kaigi]. Tokyo: Chikuma shobō.

Hayakawa, Tadanori. Translation by Joseph Essertier. 2017. “The Story of the Nation: ‘Japan Is Great,’” 15(6-4).

Ienaga, Saburo. 2002. Taiheiyo sensō [Pacific War, Tokyo: Iwanami shoten.

Ishibashi, Gaku and Narusawa, Muneo with an introduction byYoungmi Limtranslated bySatoko Oka NorimatsuandJoseph Essertier. 2017. “Two Faces of the Hate Korean

Campaign in Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 15 (24-5).

Koyama, Emi. 2015. “The U.S. as ‘Major Battleground’ for ‘Comfort Woman’ Revisionism: The Screening of Scottsboro Girls at Central Washington University,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 13 (22-2).

McNeill, David. 2015. “Nippon Kaigi and the Radical Conservative Project to Take Back Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 13 (50-4).

Mitchell, Jon. 2015. “U.S. Marines Raise Tensions on Okinawa,” Counterpunch. March 2.

Norgren, Tiana. 2001. Abortion before Birth Control: The Politics of Reproduction in Postwar Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nogawa, Motokazu and Nishino, Yumiko. Translation by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen. 2014. “The Japanese State’s New Assault on the Victims of Wartime Sexual Slavery.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 12 (51-2).

Osaki, Tomohiro. 2017. “Imperial Rescript on Education making slow, contentious comeback” The Japan Times. April 11.

Repeta, Lawrence. 2017. “Backstory to Abe’s Snap Election – the Secrets of Moritomo, Kake and the “Missing” Japan SDF Activity Logs,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 15 (20-6).

Rubinger, Richard. “Education in Meiji Japan,” (De Bary, Theodore, Carol Gluck, and Arthur E. Tiedemann [eds.]. 2001. Sources of Japanese Tradition: 1600 to 2000. New York: Columbia University Press.), 81-116.

Ruoff, Kenneth J. 2001. The People’s Emperor Democracy and the Japanese Monarchy, 1945-1995. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: The Harvard University Asia Center and Harvard University Press.

Sansai bukkusu (ed.). 2016. Nippon Kaigi no Jinmyaku [The Human Network of Nippon Kaigi]. Sansai mook, vol. 899. Tokyo: Sansai bukkusu.

Shūkan Kinyōbi and Narusawa, Muneo (eds.). 2016. Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō Nippon Kaigi and the Association of Shinto Shrines].Tokyo: Kinyōbi.

Sugano, Tamotsu. 2016. Nippon Kaigi no Kenkyū [A Study of Nippon Kaigi]. Tokyo: Fusōsha.

Tawara, Yoshifumi. 2015. “The Abe Government and the 2014 Screening of Japanese Junior High School History Textbooks,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 13 (17-2).

Tawara, Yoshifumi. 2016. Nippon Kaigi no Zenbō: Shirarezaru Kyodai Soshiki no Jittai [The Complete Picture of Nippon Kaigi: The Unknown Reality of a Mammoth Organization]. Tokyo: Kadensha.

Tawara, Yoshifumi. 2017. “What is the Aim of Nippon Kaigi, the Ultra-Right Organization that Supports Japan’s Abe Administration?” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 15 (21-1).

Tsukada, Hotaka (ed.). 2017. Tettei kenshō nihon no ukeika [Thorough Investigation of Japan’s Turn to the Right]. Tokyo: Chikuma shobō.

Uesugi, Satoshi. 2016. Nippon Kaigi towa Nanika: “Kenpō Kaisei” ni Tsukisusumu Karuto Shūdan [What is Nippon Kaigi? A Cult Group Rushing toward “Constitutional Revision”]. Tokyo: Gōdō shuppan.

Yamaguchi, Tomomi. 2014. “‘Gender Free’ Feminism in Japan: A Story of Mainstreaming and Backlash,” Feminist Studies. Vol. 40, No. 3 (2014), 541-572.

Yamaguchi, Tomomi, Saito, Masami, and Ogiue, Chiki. 2012, Shakai Undō no Tomadoi: Feminizumu no “Ushinawareta Jidai” to Kusanone Undō [Social Movements at a Crossroads: Feminism’s “Lost Years” vs. Grassroots Conservatism]. Tokyo: Keisō shobō.

Yamazaki, Masahiro. 2016. Nippon Kaigi: Senzen Kaiki eno Jōnen [Nippon Kaigi: Passions to Return to Prewar Japan], Tokyo: Shūeisha.

Notes

This round-table took place in August before the Lower House election on October 22, 2017. In July, CNBC had reported on “the biggest collapse in the cabinet approval rating” for Abe since his reelection in 2012, to below 30 percent. The election produced a victory for the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito despite the low approval ratings for the Abe administration. The Party of Hope ended up losing seven seats and its leader Koike Yuriko stepped down to take responsibility for the defeat.

Nippon Kaigi has deeply influenced the Abe administration’s new approach to constitutional revision. Abe proposed adding a clause about the Self-Defense Forces to Article 9 on May 3, 2017. This proposal took place in a video message to a rally calling for constitutional revision organized by “Utsukushii Nippon no Kenpō o Tsukuru Kokumin no Kai” [Citizens’ Association to Create a Beautiful Constitution for Japan]. The timing coincided with the publication of Ito Tetsuo’s “Kenpō kaisei: ‘sanbun no ni’ kakutokugo no kaizen senryaku” [Constitutional Reform: Strategies for constitutional revision after gaining a two-thirds majority] in The Japan Policy Institute’s journal Asu eno sentaku (September 2016, 18-22). One of his proposals was to add a third paragraph about the Self-Defense Forces to Article 9. The Japan Policy Institute is a think tank group shaped by Nippon Kaigi members, which has been the brains behind Abe. Ito, the founder, is also a board member of Nippon Kaigi. It is clear that Abe’s proposal was based on the Institute’s proposal.

Since Abe’s announcement in May 2017, the mass movement for constitutional revision led by Nippon Kaigi and the National Citizens’ Association to Create a Beautiful Constitution for Japan has narrowed their target. This followed the article’s suggestion to focus constitutional revision on “the emergency situation clause,”, and “the specification of the Self-Defense Forces.”

As of August 2018, the movement for constitutional revision continues, although there is a degree of internal resistance from some LDP members. Abe, who was shaken by the Moritomo and Kake scandals, is preparing to introduce a proposal for constitutional revision as part of his political agenda as he runs for a third term as LDP president in the fall of 2018. His opposing candidate Ishiba Shigeru seems to have different views about the speed and the way to proceed towards constitutional revision, yet is also a firm advocate of constitutional amendment and the removal of the second paragraph of Article 9.

Both the National Citizens’ Association to Create a Beautiful Constitution for Japan and the Japan Policy Institute have narrowed their objectives to the specific inclusion of the Self-Defense Forces in Article 9, and have downplayed the idea of adding a clause to cover emergency situations and revising Article 24.

Yamakawa Akio (1927-2000) was a critic, editor, and publisher. Active in the movement to democratize high schools in 1945, Yamakawa joined the Democratic Youth of Japan as a student at Naniwa High School in Osaka. Later, at the University of Tokyo, Yamakawa joined the Japanese Communist Party in 1948 and remained a member until 1972. In the context of this round-table, Hayakawa suggests two of Yamakawa’s works are particularly relevant. One is “Nihon-Chosen-Amerika: Nikkanbei no Taisei Yuchaku o Abaku” [Japan-Korea-United States: exposing the systematic collusion among the three countries] for the journal Gekkan jichiken, a 12-part series begun in May 1977. The second is Scott Anderson and Jon Lee Anderson’s Inside the League: The Shocking Expose of How Terrorists, Nazis, and Latin American Death Squads Have Infiltrated the World Anti-Communist League (Dodd Mead, 1986) on which he worked as editor of the Japanese translation (Insaido za rīgu: sekai o oou tero netto wāku, translated by Kondo Kazuko, Shakai shisosha 1987).

Chamoto Shigemasa (1929-2006) was a freelance journalist known for his investigative reports on the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity (now the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification). After fighting in the Asia-Pacific War as a child soldier and as part of a special attack unit (tokkōtai), Chamoto was a critic of militarization in postwar Japan and published numerous works including Documento Gunkaku Kaiken Chōryū [Documenting the Trend of Military Reform] (Satsukisha, 1983). He was one of the organizers of Kyūjō masukomi no kai (The Article 9 Association of People in Mass Media).

The term danjo kyōdō sankaku literally means “co-participation and co-planning by men and women.” On the decision to use the word sankaku, meaning “participation and planning,” committee member Osawa Mari writes that “since the word ‘sanka’ (participation) is used to mobilize the masses in Japan, ‘sankaku’ (participation and planning) was chosen in order to emphasize that people are participating in the decision-making process” (Osawa, Radikaru ni katareba: Ueno Chizuko taidanshū [Speaking radically: a collection of dialogues with Ueno Chizuko], edited by Ueno Chizuko, Heibonsha: Tokyo, 2001, p. 17). The committee chose danjo kyōdo (cooperation between men and women) despite its lack of clarity because many LDP politicians strongly disliked the word danjo byōdō (gender equality). Nevertheless the government had to use “gender equality” as the English translation of this phrase.

In 1996, the Council of Gender Equality appointed by the Cabinet Office published two reports titled Danjo Kyōdō Sankaku Bijon or A Vision of Gender Equality and Danjo Kyōdō Sankaku Shakai 2000-nen Puran (A National Plan for Gender Equality for the Year 2000). According to The 1999 Basic Act for a Gender-Equal Society (Danjo Kyōdō Sankaku Shakai Kihon-Hō), danjo kyōdō sankaku shakai is defined as “a society in which both men and women, as equal members of society, are given opportunities to freely participate in activities in any fields of society and thereby equally enjoy political, economic, social and cultural benefits as well as share responsibilities” (Basic Act for Gender Equal Society [Act No. 78 of 1999]). After Danjo Kyōdō Sankaku Kihon Keikaku or Plan for Gender Equality 2000 was announced in 2000, many local governments began issuing ordinances that complied with the central government’s plan (See Yamaguchi, 2014, 545-546)

The term jendā furī or “gender free” became popular among policymakers, central and local administrators and educators after its introduction in 1995 in a handbook for school teachers and in a project report about gender equality in school education, both published by the Tokyo Women’s Foundation. The term “gender free” was meant to mean an attitude of being “free” from gender differences rather than aiming at achieving legal or institutional gender equality. Although no feminist scholars were part of the making of “gender free,” feminist scholars in women’s and gender studies later participated in various projects around the term, sponsored by local governments. From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, conservative critics and media embarked on a backlash against feminists, criticizing “gender free” as a repudiation of sexual differences and an attack on traditional gender roles and values. (Yamaguchi, Saito, Ogiue 2012, pp. 2-47; See also Tomomi Yamaguchi, “‘Gender Free’ Feminism in Japan: A Story of Mainstreaming and Backlash,” Feminist Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3 (2014), pp. 541-572).

Amid the scandal resulting from state-owned land being sold to Moritomo Gakuen at an extremely low price in February 2017, Tsukamoto Kindergarten, which is operated by Moritomo, also drew public criticism of its curriculum under which students were instructed to recite the Imperial Rescript on Education every morning (Osaki 2017). Promulgated in 1890, the rescript was seen as encompassing “the highest moral norms for public education under the Meiji constitution” (Ienaga 45). The rescript or chokugo refers to the words uttered by the emperor to express his will and thoughts. It was regarded as sacred and absolute. The rescript on education, which was distributed to every school and read on important occasions with one’s head bowed before a set of portraits of the emperor and empress, emphasizes “loyalty” and “filial piety” from family members to the nation. Through this mental and physical practice, the rescript was used to have children and young people internalize a sense of awe and submission to the emperor and his state. Especially the passage—“should emergency arise, offer yourselves courageously to the state (giyū kō ni hōshi); and thus guard and maintain the prosperity of our imperial throne coeval with heaven and earth” (Rubinger, 109)—was a pillar of militarism inspiring people to die for the emperor and his empire (Ienaga 46; see also Dower 33-34). After Japan’s defeat, The Ministry of Education announced in October 1946 that students should no longer recite the rescript. Both Upper and Lower Houses in June 1948 passed a resolution confirming that the rescript was no longer in effect and would be excluded from public education.

Seichō-no-Ie was founded by Taniguchi Masaharu (1893-1985) in 1930. As of July 2018, it had over 1.5 million members, according to the group’s website (http://www.jp.seicho-no-ie.org/about/index.html). Seicho no Ie actively participated in postwar right wing religious movements to re-establish practices GHQ had abolished, such as commemorating Foundation Day (1951-1966) and using the reign-name system (Ruoff 162 and 194). In 1983, however, Seichō-no-Ie announced it would withdraw from all political activity. Under the current leader, Taniguchi Masanobu, some followers and related organizations left Seichō-no-Ie and founded a new movement based on founder Taniguchi Masaharu’s teachings; these followers who left the organization include movement leaders heavily involved in Nippon Kaigi. In the 2016 Upper House Election, Seichō-no-Ie issued a statement that its beliefs are at odds with the political attitude of the Abe administration and Nippon Kaigi. The current leaders are interested in environmental issues, which departs from the previous approach of Seichō-no-ie.

Kagoike Yasunori (b. 1953) is the former president of Moritomo Gakuen. In July 2017, Kagoike and his wife Junko were arrested for fraud in purchasing state-owned land in Osaka. Prime Minister Abe’s wife Akie was honorary principal of the elementary school that planned to use the land for its new building. Her involvement in this suspected fraudulent deal has been under public scrutiny (The Japan Times, “Kagoike arrest isn’t end of story.” August 2, 2017). Kagoike was summoned to testify under oath in March 2017. According to Nippon Kaigi’s website, Kagoike was a member until 2011.

Yamatani Eriko (b. 1950) has been an LDP member of the Upper House since 2004. Yamatani is a member of Nippon Kaigi’s Diet Members’ League. Under the Abe administration, she has held positions including Special Adviser to the Prime Minister for Educational Reform (2006-2007), Chairperson of the National Public Safety Commission (2014-2015), Minister in charge of Ocean Policy and Territorial Issues (2014-2015), Minister in charge of the Abduction Issue as well as Minister in charge of Building National Resilience (2014-2015).

The ultra right wing group Zaitokukai was founded in 2006 by Sakurai Makoto (b. 1972). The group sees zainichi Koreans as recipients of social and economic “privileges” and campaigns using hate speech and demonstrations. See Ishibashi and Narusawa 2017.

“Koike’s opposition to foreign residents’ right to vote clashes with her call for diversity” October 4, 2017 The Mainichi

Ishibashi and Narusawa 2017; “Koike says no to eulogy for Koreans killed in 1923 quake” August 24, 2017, The Asahi Shimbun; “Koike’s silence on Koreans slain after 1923 quake fuels criticism” September 2, 2017, The Asahi Shimbun; “Tokyo gov. skips eulogy to Koreans massacred after 1923 quake” August 25, 2017, The Mainichi Koike again did not attend the ceremony this year.

The reign-name legalization movement or Gengō hōseika undō (1968-1979) was a right wing grassroots movement to re-establish the reign-name system that had been abolished during the Occupation.

Yasukuni Shrine was cut off from state control and became a religious corporation after Japan’s defeat in World War II. The ‘Bill for the establishment of state support for Yasukuni Shrine’ [Yasukuni Jinja Kokka Goji Hōan] was designed to allow the shrine to officially host events such as memorials honoring the war dead. While it was submitted to the Diet every year from 1969 to 1974, the bill never passed.

Nihon Seinen Kyōgikai was founded in 1970 at Nagasaki University. Nippon Kyōgikai (Japan Council) was established in 2005 to appeal to a wider range of ages than just college students, but the two groups are substantially the same organization sharing the same office and official website. See also Keigo Kawasaki “As I See It: Nippon Kaigi and the Debate over Constitutional Division,” The Mainichi, December 17, 2016.

[1] Nippon Kaigi established Atarashī kyōiku kihon hō o motomeru kai [Association for a new Fundamental Law of Education] in September 2000 (led by Nishizawa Junichi, then the president of Iwate Prefectural University). Since then, the group has lobbied the government and the LDP for the reform of the Fundamental Law of Education. At the same time, Nippon Kaigi succeeded in helping pass a series of resolutions in local assemblies seeking such reforms and launched a massive national petition campaign in 2004. Prompted by this movement, the Koizumi Junichiro administration proposed a revision of the Fundamental Law of Education in 2006, put it to the Diet, and it passed. The reformed law (the official English translation is Basic Act on Education explicitly states that, following Nippon Kaigi’s demand, a goal of education is “cultivating” a “sense of morality” and “love of country,” and it includes an emphasis on “education in family.” Based on this new “basic act,” elementary and middle schools are required to teach “love of the country,” “National Flag and National Anthem,” “Japanese mythology,” and “significance of national defense and the role of Self-Defense Forces”.

The Fundamental Law of Education was established in 1947 in response to ultra-nationalist education before and during the wartime. The 2006 revision added new educational goals such as “the public sprit,” respect for “tradition,” and “love of the country.” It also made several changes, one of which is that guardians for children have the “primary responsibility” for their education. There is a criticism that it strengthens the state control over education. The “reform” of the law was one of the important goals for Nippon Kaigi.

Nippon Kaigi responded to concern that women are less supportive of the constitutional amendment than men by publishing Joshi no Atsumaru Kenpō Oshaberi Kafe [The Cafe where Girls Get Together to Chat About the Constitution] edited by Momochi Akira (Tokyo: Meiseisha, 2014) along with a manga and video. They also organized gatherings for women nationwide under the same title. The gatherings are reported on Nippon Kaigi’s website. On the gender gap around constitutional revision, see the poll conducted by NHK in 2017.

Sakurai Yoshiko (b. 1945) is one of the “females in the vanguard of the history wars” for the rightwing camp (Mark Ealey and Satoko Norimatsu, “Japan’s Far-right Politicians, Hate Speech and Historical Denial — Branding Okinawa as ‘Anti-Japan’,” and a leading advocate of constitutional revision who works closely with the Abe Administration (see Tawara Yoshifumi, “What is the Aim of Nippon Kaigi, the Ultra-Right Organization that Supports Japan’s Abe Administration?” ). Sakurai founded Kokka kihon mondai kenkyūjo [Japan Institute for National Fundamentals] in 2007 and is its chairperson. Before becoming a prominent rightwing activist, Sakurai was a journalist, an anchorwoman for Nippon Television’s news show from 1980 to 1996, and an award-winning author of non-fiction books including Eizu hanzai: Ketsuyūbyō kanja no higeki [AIDS crime: a tragedy of hemophilia patients] (Chūō kōron: Tokyo, 1994).

Ito Tetsuo (b. 1947) founded Japan Policy Center in 1984 and is currently its representative. Okada Kunihiro (b. 1952) is the director of Japan Policy Center. Kosaka Minoru (b. 1958) is research director of the Center.