Part I

In June this year VFP-ROCK (Veterans for Peace Ryukyu-Okinawa Chapter International) drafted a formal letter – military style – based on research by ROCK member Makishi Yoshikazu, pointing out that Marine Corps Air Station Futenma (MCAS Futenma), by having no actual clear zones at either end of its airstrip, is in violation of US Military safety regulations and, for the safety of both the residents living and working around the base and the Marines flying aircraft in and out of the base, ought to be shut down immediately. We mailed signed copies of this letter to eleven US government officials, beginningwith Secretary of Defense James Mattis. We then rewrote the letter in the style of news commentary and published it in The Diplomat in its March 30, 2018 edition. A slightly revised version of that article is, with The

Diplomat’s permission, printed here.

In 2003 then US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld flew over Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Futenma, Okinawa, looked down, and declared it to be “the most dangerous base in the world.” Of course there are many bases, including some in war zones, that could contest that honor. The question is, what did Rumsfeld see that shocked him into making this extreme statement? He saw an airstrip smack in the middle of a crowded city, with residences, parks, schools, businesses, right up to the fence.

|

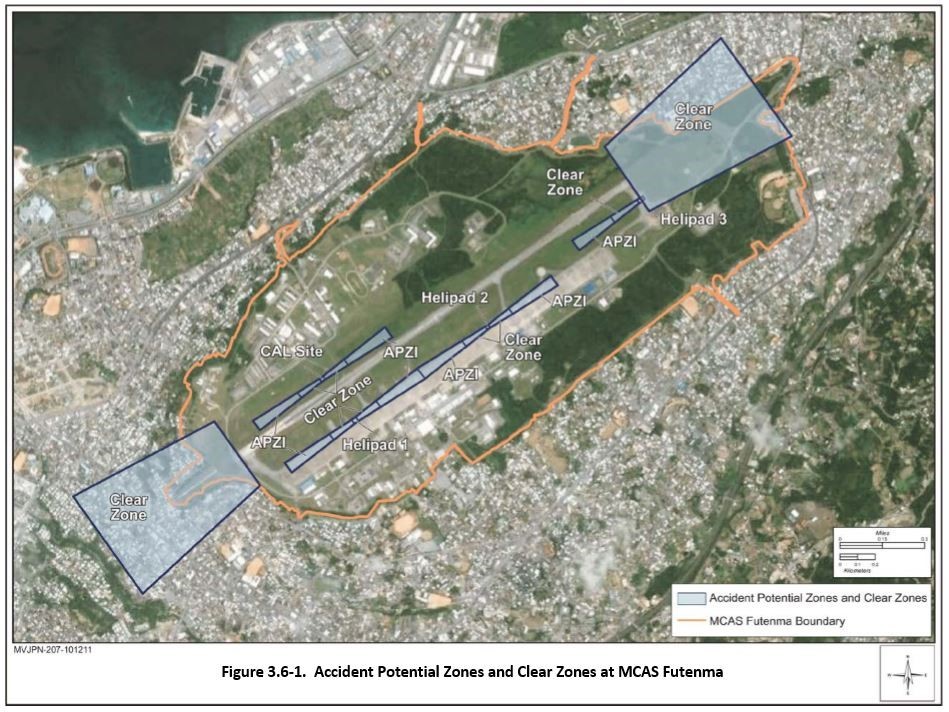

Image from the April 2012 report “Environmental Review for Basing MV-22 Aircraft at MCAS Futenma and Operating in Japan,” published by Marine Corps Installations Command-Pacific. |

While Rumsfeld is not known as an expert on aeronautical safety, his instincts were correct. The situation of MCAS Futenma is in direct violation of the safety standards set down for military airfields by the US Department of the Navy, in accordance with Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations. These standards include, among other things, the requirement that at each end of any runway there must be a clear zone, free of all construction other than airport lighting. The Department of the Navy directive OPNAVINST 11010.36c states, “Clear zones, areas immediately beyond the ends of runways and along primary flight paths, have the greatest potential for occurrence of air accidents and should remain undeveloped.” (4.a.[1]) “The clear zone is required for all active runway ends.” (4.b.[1]) “No structures (except airfield lighting) buildings or aboveground utility/communications lines should normally be located in clear-zone areas on or off the installation.” (Note 4 to table 2)

The word “normally” indicates that there may be exceptions. But the Department of the Navy directive sets out a way of dealing with those. Of course where there are exceptions – buildings in clear zones – the Navy doesn’t have the authority to command their owners to raze them. Rather, the directive establishes the Air Installations Compatible Use Zones (AICUZ) program. The AICUZ program requires base commanders to cooperate with local governments in establishing clear zones through the use of zoning laws and other means within the local government’s jurisdiction. The purpose of this is described as twofold: “to protect the public’s health, safety and welfare and to prevent encroachment from degrading the operational capability of military installations in meeting national security.” (Cover letter to OPNAVINST 11010.36c) The purpose, that is, is twofold: to protect the people living or working near the base from death or injury, and to protect the base from being shut down.

The directive states that AICUZ programs are required for bases within the US and its territories and possessions, and that they “may be developed” at bases in foreign countries. That means they are not required. But at MCAS Futenma an AICUZ program exists, though for “noise study only”. (appendix [b]) As for clear zones, the aerial photograph above shows that MCAS Futenma has adopted the perfect bureaucratic solution: the requirement to have clear zones has been met by simply designating two areas (largely off the base) as “clear zones” while doing nothing actually to clear them. This, presumably, is what shocked the not easily shockable Donald Rumsfeld. Every USMC Air Facility inside the US has clear zones entirely within the base. Futenma base isn’t large enough to do that.

|

Futenma air station, surrounded by homes and businesses. Image Credit: The Diplomat |

None of this is unknown to the Marines who work in MCAS Futenma, or to the people in the Department of the Navy who oversee it. On the contrary, it was after assessing these dangers – and the threat they pose to the entire US military presence in Okinawa – that the US-Japan Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) announced in 1996 that Futenma base would be closed down by 2003, on the condition that the military units within it would be relocated somewhere in northern Okinawa. The great bulk of the Okinawan people rejected this condition, demanding that the operation be moved out of Okinawa. 2003 came and went; 2004 saw the terrible crash of a CH 53 Sea Stallion into one of the school buildings on the Okinawa International University’s campus. (If that building hadn’t been there, those boys might have nursed their helicopter along a couple hundred yards more, and made it back into the base. That no one was killed was blind luck.) Since then another 14 years have passed (total 22) and still, at the time of this writing, actual reclamation work – that is, work on the replacement facility itself – has yet to begin.

Aircraft safety is not simply a matter of following regulations. The dangers are real. The Navy Department directive distinguishes between two aspects of safety: “the probable impact area if an accident were to occur” and “the probability of an accident occurring.” The area that ought to be a clear zone is a probable impact area both because every aircraft using the runway flies over it, and because they all fly over it at low altitude. But from the standpoint of pilots and crewmembers, the danger increases if it is the location of multi-storey buildings, telephone poles, enterprises that emit smoke, bright lights, electromagnetic waves, or parks that attract birds. It is important to remember that by far the greatest number of people killed or wounded in US military air accidents are the pilots and crew.

Defenders of MCAS Futenma often say, Well, it was the Okinawans who built their houses next to the base, of their own will. So the danger is their fault. This ignores the fact that the base was originally built right after the Battle of Okinawa, when the Okinawan people were being held in concentration camps. The military bulldozed the villages and farmlands that were there, expropriated the land, and built the base. It is odd to blame people who were driven out of the area, for living nearby. It would also be odd for the military to use this blame shifting as an excuse for inaction, given that the situation endangers its own personnel – and its own bases.

Fixing blame may be a job for politicians, but not for safety officers. Neither trying to “turn the clock back” by razing all the construction inside the clear zones, nor waiting, fingers crossed, for the replacement facility to be built at Henoko in northern Okinawa (which will not be completed for decades, if ever) is a solution. MCAS Futenma is, from a safety standpoint, untenable, and there is no way to remedy this. Calling it “an accident looking for a place to happen” is inaccurate, because the place is already known, and the accidents are already happening. Helicopter parts are regularly falling into residential areas – most recently last December 13 when a window from a helicopter dropped into the playground of Futenma Daini Elementary School (located in the base’s pseudo clear zone); just six days earlier a smaller helicopter part landed on the roof of a daycare center (also within the pseudo clear zone). Again blind luck prevailed and no one was injured, but at the elementary school the students are now doing evacuation drills just in case. This is all in the context of a steady stream of accidents, not all directly connected with the clear zone problem but very much in the forefront of Okinawan people’s consciousness: the Futenma based C-53 that went down in flames in a farmer’s field last October, the Kadena based F-35A that dropped a panel into the sea the following November, the Futenma based MV22 Osprey that went down in the sea in December 2016 – the list is long.

Now it is just a matter of waiting for The Big One, that being the one that drives the US military out of Okinawa altogether. Gambling that no such accident will happen over the next 20 or more years is wildly unrealistic – and amounts to gambling with the lives both of Okinawans and of young Marines. The smart thing will be to shut down MCAS Futenma now.

Part II

The fact that MCAS Futenma is dangerous is not unknown to the US Defense Department, nor is it something they try to hide. On the contrary, it is their main argument (to most Okinawans, their only potentially persuasive argument) in defense of building a new USMC airbase in the northern fishing village of Henoko. As the population density of Henoko is far less than that of Ginowan City, where MCAS Futenma is located, and as the airstrip will be located offshore and have no need of clear zones, its accident rate will be (so the argument goes) far lower than that of the Futenma base.

But it seems it’s not that simple. On April 9 – just a week after the above-mentioned article appeared in The Diplomat – The Okinawa Times ran a front page scoop revealing that in 2015, the Japanese Defense Agency sent a letter to the Okinawa Electric Power Company informing it that 19 of its steel transmission towers exceed height limitations that will come into effect once the new airstrip is built, and will need to be removed. This letter remained unknown to the public for three years, until The Times obtained a copy. An Okinawa Electric spokesperson told the Times that as this is public business the company expects the government to foot the cost. But there’s a legal problem. As this height limit is a US regulation, and most of the towers are on private land outside the base where US law doesn’t apply, the government may have no legal basis for requiring Okinawa Electric to remove them, and no legal basis for compensating the company for that work. What is clear is that, three years after the letter was sent, there is no sign of work beginning.

But there is more. According to The Japan Times, if the safety regulations that will come with the new base will render those (presently legal) towers in violation of permitted height limits, other buildings on the hills nearby are equally high, and also will have to be declared in violation of the safety rules. Among these are an elementary school, the Okinawa Campus of the National Institute of Technology, and (are you ready for this?) the US military’s Henoko Ordnance Depot. (See the illustration below.)

|

When asked by The Times what the Defense Agency was going to do about all these height violations, the Agency spokesperson replied, “We will consult with the US military officials and take appropriate action.”The spokesperson at the National Institute of Technology expressed surprise on learning from The Times reporter that their brand new campus was to be rendered in violation of military height regulations, and said that the Defense Agency had never contacted the Institute about that. Why the Defense Agency contacted Okinawa Electric and no one else remains unclear. Perhaps they were haunted by the memory of the 1998 accident in Italy, when a US military jet cut a gondola cable sending 20 tourists to their deaths. Or perhaps those multiple electric cables simply look like plane catchers, designed to snare aircraft and pull them out of the sky. But as for fearful images, they would do well to remember Friday, August 13, 2004, when a Marine helicopter trying to get back to Futenma Base crashed into the administration building of Okinawa International University, exploded, and burned (miraculously no one was killed).

So it seems that the casual attitude towards Okinawans’ safety that characterizes Japan’s Defense Agency and is organizationally built into the Marine Corps units stationed in MCAS Futenma [the technical term is “structural discrimination”] is going to survive the move to Henoko. Indeed, the new Henoko Base may stand a good chance of retaining the title, “the most dangerous base in the world”.

(Part II was written with the help of Teruya Masafumi and Makishi Yoshikazu.) This image is based on the US Defense Department’s Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC 3-260-01 17 Nov., 2008). Height limit is pictured as a horizontal surface 46 m. above the airfield (therefore 55 m. above sea level) and extending 2,286 m. from its edge. Anything protruding above that is in violation. The exact height of the ordnance depot is unclear as it is at an unknown depth underground. (The Okinawa Times, 12 April, 2018. English adaptation by Makishi Yoshikazu)