Abstract:

For many people outside the South Korean popular music (K-pop) world, the December 2017 death of pop star Kim Jonghyun was a sad, but abstract event. Jonghyun, and dozens more like him, is a type of Korean celebrity known as an “idol.” In addition to being popular within Korea, idols are the public face of K-pop, which has become a worldwide phenomenon. This has made idols into incarnations of Korea and Korean culture, and brought the public’s powerful disciplining gaze to bear on these young performers. In this paper, we explore how characteristics of life in contemporary Korea—including a high suicide rate, and intense pressures in education and employment—compound with idols’ years of intense training in singing and dancing without adequate attention to physical, much less mental, health. Although this is the first incident of an A-list K-pop idol committing suicide, we propose that the nature of contemporary Korean celebrity, together with specific factors defining the lives of Korean youth, create an environment where suicide may become even more prevalent, escalating Korea’s suicide rate, which is already among the world’s highest. Finally, we discuss the potential impact of Jonghyun’s suicide on K-pop fans.

Keywords: Suicide, Jonghyun,2 SHINee, spectatorship, netizen, K-pop, celebrity, South Korea

The Note3

|

Introduction:

This suicide note, reproduced in part above, was passed from Korean popular music (K-pop) superstar Kim Jonghyun to the singer Nine9 (a member of the indie group Dear Cloud) before the twenty-seven year old star took his own life. Immediately after the news spread of Jonghyun’s suicide, legions of fans pointed to his 2017 duet with Taeyeon, “Lonely,” the lyrics of his other songs, comments made in interviews, and his final Instagram livefeed as revealing in hindsight his long struggle with depression.

|

|

Kim Jonghyun debuted in 2008 as a member of SHINee, roughly three years after he was scouted as a fifteen-year-old. The five-member K-pop group is one of the industry’s most successful and enduring acts, the source of multiple number one hits. They are managed by SM Entertainment (SME), the leading company in K-pop. Jonghyun was one of the first artists from SME to become involved with songwriting and producing, penning hits for SHINee, other K-pop artists in the industry, as well as for his own solo releases.4 He won awards for his work—such as the 2015 MBC Entertainment Award—for the radio division.5 In recent years, he had been actively engaged with numerous performances and recordings. Despite his prodigious success, on December 18th, 2017, he used a frying pan to burn coal in a well-sealed room, sent a good-bye text message to his sister, and died of complications from carbon monoxide poisoning.6

Legions of fans mourned worldwide at the news of Jonghyun’s death, which received coverage from outlets like CNN,7 the Guardian,8 The LA Times, The Washington Post, The Telegraph, The Daily Mail, Forbes, Newsweek and other major English-language publications‒a testament to the global nature of the Hallyu phenomenon (Hallyu is a term encompassing all of Korea’s internationally popular cultural products, including films, dramas, games, and music). An article in one of Israel’s most widely distributed newspapers read, “South Korea Mourns: A Pop Star Commits Suicide and Leaves a Letter to his Fans.”9 A local fan writes in the comments section:

“When I heard about this for the first time, I was with a friend, another K-pop fan, and we could not stop crying. He was dear to my friend, her favorite. When they [sic] share their private-life experience with you, they make you feel connected to the person, as if you know [the idols] personally.”10

Similar reports were written on high-traffic K-pop-related websites, such as allkpop.com,11 as well as music-related publications like Billboard12 and Rolling Stone.13 In Arabic, the news outlet Al Bawaba (“The Portal”) reported that “Korean singer Kim Jonghyun sends emotional words to his sister and then commits suicide!”14 In China, where K-pop is immensely popular, Jonghyun’s death was covered by such outlets as Entertainment China;15 in Hong Kong, by South China Morning Post;!6 and in Taiwan, by Liberty Times.17 The singer, well known for having released tracks in Japanese, was mourned in Japan’s Asahi Shimbun;18 Japanese celebrities remarked upon his passing,19 and Japanese fans gathered at concert venues where SHINee had performed to offer silent prayers.20 One specialized online store, K Drama Connections, even announced its intention to open a dedicated helpline specifically as a response to Jonghyun’s death.21 The profits from commemorative SHINee merchandise, the store announced, would be used to create a helpline for people suffering from stress and depression—the eventual goal was to have a multi-lingual helpline available to K-pop fans around the world, reflecting the global reach of K-pop culture. Brazil, Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam similarly saw coverage of Jonghyun’s death in breaking news. In Korean newspapers, magazines, and online news aggregators such as Naver, the coverage was non-stop.

For many people outside the K-pop world, the shared cultural sphere creating new communities around vibrant pop culture texts (Otmazgin 2016, Chua 2004), the death of a pop star may seem a sad, but abstract event. Anyone can recall any number of international pop stars, such as Prince and David Bowie, who have passed away in recent years. Even in Korea, there have been many celebrity deaths, including over a dozen by suicide, in the past decade.22 When young celebrities die from drug overdoses, traffic accidents, or suicide, it is not uncommon for people to feel frustration over someone who “had it all” treating life so cavalierly. Less commonly do we consider our role, our culpability in their deaths, outside of the worry that others will succumb to the same demons, but Jonghyun’s death presents an opportunity for us to consider these factors more attentively.

Jonghyun and dozens more like him are a type of Korean celebrity known as an “idol.” Idols are the public face of K-pop, which has become an increasingly worldwide phenomenon, with an audience that is growing—both geographically and demographically—beyond its original focus on tweens and teens in Korea. Their growing presence on the global stage has given idols the additional responsibility of representing Korea and Korean culture to the rest of the world (Epstein 2015; Fuhr 2015; Elfving-Hwang 2013), bringing the Korean public’s powerful disciplining gaze to bear on these young performers, who already face incredible pressure. They are acutely aware of the fleeting nature of celebrity and the intense competition from other hopefuls; they are subject to the commercial imperatives of their respective agencies, which regulate and micromanage their lives; and they are constantly being monitored, adored, and scrutinized by hundreds of thousands of anonymous individuals online.

As has been theorized elsewhere, the “parasocial relationships constructed between the idol and the fan” can mean that younger fans are “exposed [to] and unable to resist the beauty ideals and lifestyle choices of the idols as potential role models” (Elfving-Hwang 2018: 197). The legs of the Girls’ Generation members are presented as goals to aspire to (Epstein 2015), while the frankly disclosed plastic surgery of stars, extreme diets, and details of workout regimes signal that, with effort, anyone can be beautiful (Elfving-Hwang 2018: 197). In a world built on the idea that idols are role models for youth, Jonghyun’s suicide created a deep rupture between K-pop’s glittering façade and the darker reality experienced by idols and ordinary Koreans. Fandom is constructed through the maintenance of a fantasy relationship between fan and idol, a relationship that some fans enter into in order to distance themselves from present and future stress. Although fans are familiar with the sweat equity that idols pay, this effort is consistently and cheerfully portrayed to fans as parallel to efforts fans might expend in pursuing their own dreams. Therefore, we argue that Jonghyun’s breach of the unspoken contract, whereby hard work and fan adulation will bring a fabulous dream to life, created a rupture in the K-pop fantasy. Cognizant of this reality, fans in both Korea and abroad must come to grips with the heavy stresses in contemporary Korean society, as well as with the stresses in the lives of Korean idols.

In this paper, we explore how characteristics of life in contemporary Korea, such as intense educational and occupational pressures, drive the high suicide rate. This correlation, combined with the lack of adequate attention to idols’ physical, much less mental, health during their years of intense training in song and dance, provides context for Jonghyun’s suicide. We propose that the nature of contemporary Korean celebrity and specific factors defining the lives of Korean youth create an environment in which suicide may become even more prevalent, increasing Korea’s already high suicide rate. Finally, we discuss the potential impact of Jonghyun’s suicide on K-pop fans.

|

“Ring Ding Dong” was a huge hit for SHINee from their second set of releases in 2009. Jonghyun sings first.23 |

|

SHINee in concert at the Melon Music Awards, November 13th, 2013. Photo credit: By Sweet Candy (131114 Melon Music Awards) [CC BY 4.0 (here)], via Wikimedia Commons |

Suicide and Mental Illness in Korea

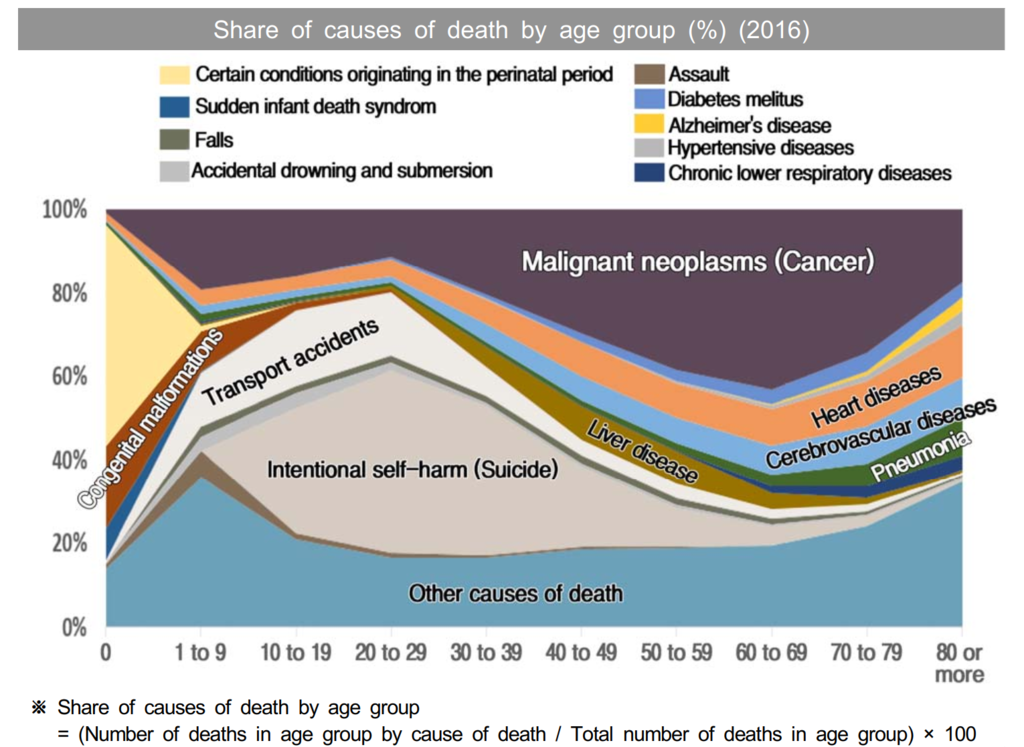

Since 2003, the Republic of Korea has recorded the highest suicide rate among the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations, including developed and developing nations such as Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, Haiti and Qatar. According to the 2015 OECD figures, 2009 was a peak year for suicides, reaching a rate of 33.8 per 100,000 persons, or a total of 15,413.. Turkey, with the lowest suicide rate in 2009, recorded just 2 per 100,000.24 According to Statistics Korea, 2016 saw 13,092 people commit suicide—a rate of 25.6 people per 100,000.25 While these rates have roughly stabilized in the past decade, suicide remains an important issue in Korean society, and as of 2016, the fifth highest cause of death,26 with previous high profile victims including former South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun and popular actress Jang Ja-yeon.27 The rapid industrialization, urbanization, and economic growth in Korea, colloquially known as the “Miracle on the Han,” initially brought hope for widespread economic prosperity, but the Asian financial crisis in 1997 caused rapid economic polarization, a decline in the middle class, and a rapidly growing Gini coefficient (Jo 2016: 290). The aftershocks even extend to causing “intergenerational inequality,” where children cannot escape their parents’ disadvantages (Ibid.), a social issue explained locally as sujeoron or “spoon theory” which claims that you cannot escape the type of spoon you are born with in your mouth (Kim HJ 2017). Research has shown the impact of the intergenerational production of inequality on depression in Korea (Jeong and Veenstra 2017). In 2016, Cho Donghyun and Kwon Hyukyong’s research revealed a particularly clear link between unhappiness and despair, and perceptions of inequality of opportunity. In Korea, both male and female suicide rates have increased, although the male suicide rate is higher and shows more dramatic jumps, such as in 1998 (after the Asian financial crisis), 2003 (domestic credit card crisis) and 2009 (impact of the 2008 American economic recession) (Kim et al 2017: 6). The same study concluded that the high degree of parental responsibility for women particularly makes women aged 30-54, during their child-rearing years, unlikely to commit suicide (Ibid.: 12).28 The largest share of suicides occurred among students, both male and female. In non-student populations, the share of suicides was highest among those of low socioeconomic status, including blue collar workers, the unemployed, and the undereducated, particularly residents in rural areas (Ibid.).

|

Figure 1: Share of Causes of Death by Age Group (2016) Source: Statistics Korea Figures for 2016. Graphic created by Statistics Korea. |

In Korea, there is a deeply rooted stigma surrounding mental illness, often originating from misconceptions of what mental illness is, as well as from negative assumptions about those who suffer from mental illness. A 2013 study examined data on depression and depressed individuals from 16 countries across the globe, including Korea (Pescosolido et al. 2013). Although the study affirmed that certain views held throughout the world, such as the majority understanding that mental illness improves with treatment or that individuals should seek help from a psychiatrist, mental health expert, or medical doctor, it revealed many worrying trends as well. For example, a considerable percentage of respondents agreed that bad character causes depression, or linked symptoms of depression with physical illness rather than mental illness (Pescosolido et al. 2013: 855). Furthermore, over 50% of respondents agreed that individuals with depression are not as intelligent, trustworthy, or productive as those without, and that depressed individuals should not be allowed to supervise others or teach children (Ibid.: 856). Other studies that looked at Korea have shown evidence of people who are known, or thought to have mental illnesses being subjected to stigmatization (Lauber and Rossler 2007).

The delays in initial treatment contact need to be viewed in the light of mental health delivery system in Korea. There, the decision of where to go for treatment largely depends on the patient’s own choice. Also, in Korea, the provision of general practitioners is in shortage, while specialists, as 85% of entire physicians, are predominant. As such, unlike countries where primary care physicians and other counselors actively participate in the care of patients with depression, in Korea, psychiatric treatment is mostly provided by psychiatrists. Free-patient choice and the loosely organized health care delivery system combined with an ingrained reluctance to psychiatric treatment in Korea may contribute to an underutilization of mental health services.

The prevalence of negative and misinformed views about depression reveals that Korea is still developing an understanding of mental illness and methods of treatment (Lee HJ et al 2017). Perhaps more troubling than the social stigma surrounding mental illness is the potential internalization of that stigma by those experiencing mental illness, as a by-product of widespread community views. Internalized stigma occurs when individuals suffering from mental illness apply negative and stereotypical views of mental illness to themselves (Drapalski et al. 2013: 264). This negative self-perception can further damage mental health, working against recovery and mental wellness (Ibid. 267). The stigma attached to mental illness makes seeking treatment a last resort for many. Misconceptions and stereotypes regarding mental illness and mentally ill individuals are pervasive in Korea, and the prevalence of community-based mental health stigmas creates an incubatory environment for stigma internalization.

A survey done by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 2011 indicated that only 15.3% of all Koreans suffering from mental illness receive treatment (Roh et al. 2016: 7).29 A large scale study based on a survey of 1,433 Korean patients in treatment for depression found that they waited, on average, 3.4 years before starting treatment for depression, although the scholars also acknowledged that their figures cannot account for those who never sought treatment (Ki et al., 2014). The study concluded that the delay in treatment could be attributed to a variety of factors, including a health care system with an overabundance of specialists—psychological treatment is carried out by psychiatrists but there is an “ingrained reluctance to seek psychiatric treatment”—and a need to expand mental health services that are not readily available in communities (Ibid., 422). In other words, an individual seeking help may have difficulty finding an appropriate professional, particularly at the time of urgent need. Even when a depressed individual does seek help from a psychiatrist, research shows that the treatment offered in Korea is often inconsistent with clinical guidelines (Yang et al., 2013). Where there is high social risk in acknowledging mental illnesses, people are less likely to seek out appropriate medical attention and may turn to harmful behaviour in the absence of proper care.

In addition to the shortcomings of mental health care in Korea, another factor behind the high suicide rate is the pervasive culture of “shame.” Anthropological approaches have proposed the classic division of cultures as motivated by fear, guilt or shame, and in shame societies, social behaviour is governed by the principle of maintaining honor and avoiding shame that could stain it. Many incidents of suicide in Korea therefore follow “dishonorable” failures—in 2009, former President Roh Moo-hyun committed suicide when his family was enmeshed in a corruption scandal, whereby his family members’ actions shamed him and stained his legacy. When confronted with a source of deep shame, other politicians and businessmen often make the same decision. In March 2018, actor and university professor Jo Min-gi committed suicide after a number of women accused him of sexual impropriety as part of Korea’s burgeoning #metoo movement.30 Victims of sexual abuse, harassment, and revenge porn have also made the decision to take their own lives after being publicly shamed.

Attitudes towards suicide in Korea have changed over the years. Before the colonial era, elite women still of marrying age were praised for committing suicide when they outlived their husbands. Confucian scholars would state their willingness to die for their beliefs when they sent strongly worded rebukes to the throne. In fact, Jeong Seunghwa, who carried out extensive research on suicide across Korean history, explains that during the Joseon Dynasty, entire families would commit suicide when male family members lost favor with the crown (2011: 184). After the Korean War, particularly among families in dire conditions, who family suicide became a serious social issue (Ibid., 185). Parents who were unable to provide for their children felt that leaving their children to fend for themselves would be crueler than killing them, justifying murder-suicide.

What do present-day Koreans think about those who commit or attempt suicide? Of course, not all suicides are received in the same way. If we loosely group suicides into those driven by private, personal reasons, and those driven by shame from a scandal, there is generally more post-mortem acceptance and sympathy towards the latter, as these individuals are seen as taking responsibility and preserving a degree of honor through their deaths. In the case of a high-profile wrongdoing, the family’s or company’s liability can end with the death of a single individual. Suicides by those who were shamed, but in retrospect are judged to be blameless (such as President Roh) generate great sympathy for the deceased. Suicides by those who cannot bear the weight of something outside of their control (as in the case of Kang Min-gyu, the vice-principal who was rescued from the Sewol ferry sinking, which killed about 250 of his Dawon High School students) tend to be met with understanding and regret by those left behind.

On the other hand, in many cases of suicide for highly personal reasons, such as mental health issues, families choose to hide the truth to the extent that some scholars have found figures on suicide to be significantly underreported in Statistics Korea data (Jeong et al 2016). This is not least because the survivors are left suffering from loss so severe that their decreased productivity impacts the Korean economy (Kim JW et al. 2017: 2). Jeong Sooim, Ben Park and Kathryn Ratcliff blame Confucian familism, noting that the “act of self-destruction has been typically seen as a serious breach of the Confucian norms” (2016: 2). Contemporary Korean families are shamed by familial suicide because from the perspective of Confucian familism, it shows a failure of the entire family (ibid. 6). Underreporting is possible because in the Korean procedures following a death, a family member or friend fills out a form about the deceased and their cause of death (unless the deceased passed away under the care of a physician or an autopsy was carried out). This means that non-professionals fill out this form in more than 60% of cases (ibid. 4), enabling the misreporting of details behind the death (often attributed to a traffic accident). The National Police Agency keeps records separate from those of Statistics Korea, and the study revealed a difference of 2,000 to 5,000 suicides between the annual figures of Statistics Korea and the higher figures of the police (ibid. 5). Naturally, the stigma that prevents accurate reporting can hobble efforts to reduce suicide.

|

SHINee in performance in Taiwan, March 21st, 2015 (SM Town Live World Tour IV). (l-r: Onew, Taemin, Jonghyun, Minho, Key). Photo credit: By Sparking (150321 SMTOWN SHINee) [CC BY 4.0 (here)], via Wikimedia Commons.] |

High-Pressure Society

Journalists, commentators, scholars, and everyday citizens are well aware that “Korea’s work and school cultures are dangerously toxic.”31 Scholars like Yi Chunghan see the issue as something caused by a depreciation of human value and blame Korea’s hyper-capitalist society (2015: 466). Korea’s high-pressure society contributes to depression, other mental illnesses, and a high suicide rate. Youth unemployment in South Korea, steadily rising since the 1997 financial crisis,32 has led to feelings of hopelessness about the future, which in turn, pose a significant risk of driving youth to suicide (Lee et al. 2010: 533). Youth unemployment refers to those unemployed between the ages of 15 and 24, in accordance with OECD and UN labor force standards, but, for studies on Korea, the range is often extended up to 29 years old, so as to account for the mandatory military service among young men (Bae and Song 2006: 4). To be considered unemployed, the individual must be currently not working but seeking employment. Despite rising trends of educational qualification and expanding ‘specs’ (specifications, referring to the individual’s specific qualities and qualifications) among Korean youth, securing employment is becoming increasingly difficult.33 This is partially due to a shift in hiring practices; in the economic downturn following the 1997 financial crisis, experienced workers were prioritized over new applicants, since the latter required investment in training (Ibid. 5).

In the last few years, narratives of despair have swirled around the peninsula, with some of its inhabitants even nicknaming the country “Hell Joseon” (Joseon was the dynasty from 1392-1910) to capture a feeling of hopelessness, particularly among the younger generation. Discussions of young people as residents of Hell Joseon, or as members of the “880,000 Won Generation” (referring to the monthly salary of a temporary or contract worker of approximately 650 USD), or the “sampo generation” (三抛世代, literally “Giving-up three generation,” a title that references the romance, marriage, and children that this generation might have to give up),34 have become so commonplace that these discourses may become self-fulfilling prophecies. Young people exhibit signs of anxiety and despair, partially due to the perception that government initiatives to address these problems have been ineffective (Song and Lee 2017: 31). For young Koreans who grew up under the narrative that studying hard and getting a good education will ensure future employment, this is devastating. With youth unemployment facilitating a feeling of hopelessness, the risk of mental illness and suicide among Korean youth skyrockets.

The Korean educational system has only become more stressful as a general sense of hopelessness spreads among youth—two decades ago, if a youth tested well on the college entrance exam, he or she could enter a top university, which would virtually guarantee lifetime opportunity and employment in Korea. Now, the panic in which students study while in high school extends into university, where each student frantically seeks to improve their chances of success on the job market. Educational inflation has become so severe that although there previously was a large difference in earnings between the college educated and those who graduated only from high school, that difference has continually fallen since the 1970s and 1980s (Kim and Choi 2015: 440). In other words, the social crowding of the education market has long since exceeded the demands of the labor market (ibid. 443). This pressure on Korean students is so intense that Korea has the highest per capita incidence of teenage suicide in the world, with an increase of 0.7% in 2016 compared to the year before.35 Students who have not scored well on crucial exams take their own lives—this is a recurring phenomenon, and even a cursory search on any news website will provide numerous results. In one case, twins texted their parents an apology for their scores before leaping to their deaths.36 In 2005, a family committed suicide together on the father’s orders because the son was not admitted into the top university. In a cruel turn of events, the son escaped the burning vehicle while his sister and parents perished.37

|

Jonghyun at a fan event in Busan, June 2016. Photo credit: By Pabian – 160606 종현 부산 팬사인회, CC BY 4.0] |

Suicide and Fame

Celebrity death creates what Margaret Gibson calls a “community of mourning,” a community that momentarily connects people from around the world, but which generally dissipates after the climax represented by some type of memorial service (2007: 1). The process of mourning tends to be a memorializing one, an intense period of reviewing memories and facts about the deceased. Fans, however, have a hard time moving on after a suicide, as they are emotionally invested in the celebrity. Fans’ relationships to the celebrity may have felt as intimate as if they were friends or even family as a result of the celebrity’s careful maintenance of parasocial relationships facilitated by social media.38 For many fans of Jonghyun, this process centered around trying to understand why Jonghyun would have taken his own life, causing them to explore deeply and often for the first time the dark side of K-pop and Korean society. Whether the fans were young Koreans with their nose to the grindstone trying to maintain hope for a bright future, or fans abroad with even less exposure to the downsides of contemporary Korea, Jonghyun’s death brought attention to the very things the bright façade of K-pop intends to conceal.

Celebrities, the object of innumerable fans’ invested hopes, dreams and aspirations, are subject to disproportionate amounts of pressure. For instance, in their work on Japanese celebrity, Patrick Galbraith and Jason Karlin illustrate one such example of “idols who stand in for the people and catalyze the feelings of the nation” thanks to their level of popularity (2012:26). The charisma of these celebrities — “a power that is not totally dissectible” (Marshall 2014: xx) — is the precondition necessary for them to enter the public eye. However, the difficulty of “[keeping] balance” between the various elements of a celebrity’s life is “a frightful list of requirements” (Inglis 2010: 230) that demands ever-increasing effort and attention, even as these idols are exhausted by their overwhelming schedules. As a product of the joint investment of a consumer culture of fans, agency executives, endorsement deals, and many other stakeholders, celebrities are handled with a “strange combination of cruelty, sentimentality, touching affection, and downright superstition” (Ibid. 16), the inherent dissonance of which amounts to significant psychological stress for the individual(s) at the core of such structures.

Fame brings with it heavy pressure and also creates a barrier between celebrities and the general public. Strain theory has been applied to understanding celebrity suicides. The theory identifies four types of strain, each of which represents being pulled in two or more directions, hence creating the strain: (1) conflicting values, (2) aspiration versus reality, (3) relative deprivation, and (4) coping deficiency (Zhang et al 2013: 230-231). Most celebrities seem to experience the most strain in reconciling aspiration with reality. While this seems to have been the case with Jonghyun, who was well known for his perfectionism, coping deficiency seems to have been a factor, as well. When more than one type of strain presents at once, the resulting strain cluster may increase the chances of suicide. In Jonghyun’s case, being a member of a group and an entertainment company with stars that shared similar hardships was not enough to overcome his personal demons. Certainly, he is not the first Korean celebrity to commit suicide. In past years, Korea has mourned the deaths of Jang Jayeon, Choi Jinsil, Chae Dongha, and other celebrities who took their own lives. However, Jonghyun, who has a significant international fanbase, is the most high-profile star to have committed suicide.39

|

“Deja-bu,” a solo song by Jonghyun featuring a guest appearance by Zion-T |

|

“She Is” was Jonghyun’s 2016 solo hit |

|

Jonghyun performs at the EXPO Arirang Pop Music Festival, July 27th, 2012. Photo credit: By livingocean (엑스포 팝 페스티벌 With 아리랑 ‘샤이니&달샤벳&이현&달마시안) [CC BY 2.0 kr (here)], via Wikimedia Commons] |

Idol Stars and Expectations of Perfection

It is widely known that idol stars are highly controlled by their management agencies in order to fulfill an image of “collective moralism” (Kim and Kim 2015). Agencies, such as SME, control all aspects of an idol’s life. Young hopefuls are recruited through street casting or rigorous auditions, the latter sometimes in the format of a reality television competition. After varying time periods spent as a trainee (sometimes exceeding seven years), the idols are organized into groups, or less often promoted as solo artists. They are often required to sign contracts, infamously nicknamed “slavery contracts” for the large latitude given to the agencies. After recruiting and training the idols, these agencies manage the idols’ image and diet regimen, and oversee selection of songs and choreography, as well as concepts for video shoots and performances—idols like Jonghyun who write (some of) their own material are less common than those who are fully crafted by the agencies. The agency also assumes the responsibility of promoting the artists, distributing their music, and placing them in TV shows and advertisements.40 The agency justifies its heavy involvement in management by pointing to the initial time and expense spent on training the artists, as well as to the costs of hiring stylists, videographers and other staff who are involved in each release following the artists’ debut.

The trainees are a relatively disposable and interchangeable part of the system. Agencies like SME employ artists—song writers, choreographers, producers and more—all of whom have greater opportunity to express their own ideas and artistic vision than the idols who serve as the face of the industry, effectively as puppets. Major agencies like SME tend to debut groups successfully, launching performers to mega-stardom, but the type of fame they experience differs from that of Western musical stars. Combining Korean cultural expectations for good behavior from stars with heavy-handed contracts, the disempowered stars feel enormous pressure to meet the demanding standards of their agencies and their fans. The only way out is for idols to wait for their contract period to end (contracts with SME are often for seven years or more), and opt not to renew their contract. However, such actions have negative ramifications not just for the idol, but for the group they belong to.

Groups like SHINee tend to have a specific role assigned to each member, and the idol system relies on each idol always maintaining the façade that the role represents their authentic self (Elfving-Hwang 2018: 194). These roles divide tasks in performance—for example, in SHINee, Onew was the leader and a back-up vocalist, Key was a rapper and back-up vocalist, Minho was the main rapper and the “visual,” (a position selected on the basis of an idol’s appearance), Taemin was the lead dancer and back-up vocalist, and Jonghyun was the group’s lead vocalist. The roles also extend to character—as in designating members as shy, funny, sexy, a little wild, clumsy and so on. Roald Maliangkay (2015) and Shin Haerin write that K-pop agencies allow a carefully scripted spice of rebellion or nonconformity, what Shin calls “the right dose of transgression” (2015: 134-5). According to Maliangkay, management companies will orchestrate expressions of rebellion so that fans will be satisfied that idols are more than puppets, that they make a creative contribution. However, because “they venture onto thin ice when challenging society’s hetero-normative foundations” (2015: 102), there are limits to the expression their management will permit. Therefore, each group is carefully manipulated to “avoid the image of complacency and mimicry,” (Ibid.) while also avoiding any behavior that could alienate the audience.

The agencies invest heavily in the trainees, but have no guarantee of a return on their investment; to increase the likelihood of success, they provide intense training in performance and related skills, arrange plastic surgery procedures, and enforce strict diet and exercise regimens. On top of the pressures to achieve performative perfection by training in dancing, singing, and acting, as well as taking private lessons in foreign languages so as to be able to sing and interview in those languages, idols must spend a considerable amount of time on achieving physical perfection. In contemporary Korean society, plastic surgery has become normalized as part of social etiquette (Elfving-Hwang 2013). Cosmetic surgery is considered an act of social consideration for others, not unlike taking regular showers and brushing one’s teeth. It is well known that many idols have used surgery to subtly perfect their appearance. Women are required to be very thin, while men are encouraged to work out and achieve muscle definition (Epstein and Joo 2012). On having a slim body, Stella Kim, an ex-trainee at SME, described a process of public weigh-ins and humiliation for those who had gained weight.41

The media participate in a narrative that glorifies the hardships idols experience. Predictably, more attention is paid to successful idols who have already overcome these hardships than to the trainees who are still struggling with them.42 However, the difficult realities of stardom should be considered more carefully, as they are an important counterweight to the glamorous illusion of fame. The physical stress that idols endure entails not only intense dieting, but also overall exhaustion and frequent injuries. In a recent but unexceptional case, Korean singer Heize was rushed to the hospital after fainting. She was previously diagnosed with pharyngitis and had to undergo surgery. Predictably, the incident was blamed on overwork; “the 26-year-old’s spokesperson said Heize’s extremely busy schedule might have something to do with her deteriorating health.”43 In the K-pop industry, having throat nodules (scar tissue in the throat due to overwork and or working through poor health) could almost be considered a rite of passage for singers, due to countless similar reports. Idols frequently injure themselves through overexertion or external factors, such as a slippery outdoor stage causing a fall. Schedules are unrelenting, with small and large performances, and other media appearances in between, making them physically difficult to sustain. In a deadly illustration of the impact schedules have on artists, in 2014, a van carrying five members of the mid-level group Ladies Code hit a guardrail when the manager sped on a rainy highway, ultimately killing two members.44

In addition to the stresses of maintaining their performance training and physical appearance, idols are also denied the chance to have a normal life. Dating, for example, is generally forbidden while stars are in the early stages of their career, and dating that occurs later is generally off-putting for fans whose fantasies are dashed. Extreme fans stalk idol stars’ every move, disclosing sightings of idols. If an idol is caught meeting a friend of the opposite gender, rumors will circulate, and sometimes be followed by an admission or denial of the relationship. Around the time of debut, and usually for a couple of years afterwards, the idols are denied cell phones, keeping them from making social media blunders, obsessing over the critical words of netizens, or having a social life. However, members of long-standing groups like SHINee are often encouraged to facilitate communications with fans through personal social media channels. Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms allow idols a window into the normal life of young people, yet almost anything they post can be twisted or politicized, further denying them a chance to live like other young adults. The constant spotlight prevents the formation of normal relationships and turns every action of a celebrity into “newsworthy” dissections, at the expense of a semblance of normal life.

Clearly, there are many deterrents on the road to becoming a K-pop star. However, if an idol falls short of industry demands or gives up their career, it can be difficult for them to change tracks, to attend university or pursue a job outside of entertainment. Many idols who debut as teenagers interrupt their high school education to accommodate the high demands of training. Some idols may feel trapped—stuck in an industry that chews up and spits out stars after a few years—and unable to see a secondary career path. Occasionally idol stars do bow out of fame, choosing to escape from an industry that seems poised to destroy them. For example, 2NE1’s Park Bom, B2ST’s Jang Hyeonseung and AOA’s ChoA have all retreated from the public eye. A few successfully re-enter the ranks of idol stars, like Sunmi who left the Wonder Girls to attend university in 2010, re-entered the group in 2015, and had a highly successful solo debut in 2017.

|

Jonghyun and Taemin performing, August 18th, 2012 in Seoul (SM Town Live World Tour III). Photo credit: By Idol Story (120818 sm콘서트-샤이니) [CC BY 2.0 kr (here)], via Wikimedia Commons] |

When Idol Stars Aren’t Perfect

Not all idol stars are successful in projecting the proper image, however, and when failings come to light, trouble ensues. From time to time, false or real accusations emerge, which can subsequently damage an idol’s career so severely that they may never recover, or they may be cast out of the industry. Such infractions can involve criminal behavior, political missteps (often in relation to military service), and sexual impropriety. Damaging criminal accusations include gambling, drunk driving, assault, and drugs. Various stars have been accused of and even convicted by the public, if not by the courts, for each of these infractions. Depending on the star and the seriousness of the charges, any allegation of such offences can seriously damage or even destroy a career. Kim Hyun-joong, former member of SS501, suffered major damage to his career from a sensationalized court battle over a physical altercation with his ex-girlfriend, as well as over a drunk-driving case. He entered the military and may, with a disciplined and newly “mature” image, manage to eventually rebuild his career. In a more extreme and recent example, Jeon Taesu, an actor who had been convicted of assaulting a taxi driver and two policemen in 2011, subsequently experienced major difficulties in getting cast. He committed suicide in January 2018.45

Taking the wrong side on a political issue or angering audiences with unpopular opinions can be damaging as well. The clearest example of this is Yoo Seungjun, a major star at the turn of the millennium. Seungjun legally avoided completing his mandatory military service by giving up his Korean dual citizenship, but in so doing, he offended nationalist sensibilities so badly that he was permanently banned from re-entering Korea. When two members of girl-group AOA, Seolhyeon and Jimin, could not identify a photo of the Korean national martyr, An Junggeun, they were denounced as lacking patriotism and basic knowledge of Korean history. They came under extreme criticism, and were forced to tearfully and publicly apologize. Finally, if it is ever revealed that a starlet has been “receiving sponsorship,” a euphemistic phrase for giving sexual favors in exchange for “investment” in a young star, it can end their career, as was the case for several unfortunate young women, perhaps most visibly G.Na. Some critical netizens have continued to condemn stars even after their fall or suicide.46

Other issues that may have once had the potential to end a career, such as Hyun Jinyeong’s prison sentence for marijuana use in the 1990s, are slowly becoming less important to the public (as a case in point, TOP’s sentence for the same charge was deferred in 2017). But more than the prison sentences and fines levied by the court of law, it is the court of public opinion and the resilience of the idol that determine whether an idol can survive an accusation or conviction. The target of severe criticism and unable to restart his career, Hyun Jinyeong attempted suicide, as well.

Stars Being Disciplined by the Public

Stars stand “at the center of powerful processes of identification” (Waksman 2015: 297), yet the nature of celebrity is less studied than the products of that celebrity. Tom Mole proposes that modern celebrity has become hypertrophic (2004). Mole means that the mechanisms of celebrity and fame culture have become visible—the management and control exerted on K-pop stars by their agencies and the fans is, as in hypertrophic celebrity, clear to observers. The star apparatus—ranging from what were once gossip-filled newspapers (now mostly websites), to publicity departments—was already becoming visible in the decade from 1910 to 1920 (Gross 2003: 98), when the “private” lives of stars were already being exploited and revealed for a public seeking to discover the authentic person, not the fictional character or public persona of the star (Ibid.). The media has increasingly participated in this erosion of celebrities’ privacy, while simultaneously criticizing themselves for doing so (Ibid., 105).

The major companies who dominate K-pop, as well as their primary movers and shakers, are a matter of public knowledge. These companies frequently issue statements either shielding the stars or addressing issues connected to them. Companies are trapped between responding to the public’s reasonable and unreasonable demands, and simultaneously balancing complex factors in the management of artists with insatiable fans. The expectation that idol stars will be perfect creates tremendous tension in the idol star production system, and it gives both agencies and the general public, the consumer base that the agency must please, power over idols.

Fans, attuned to demands for perfection, engage more intensely in a bid to support idols in perceived career danger due to netizen critique or agency neglect. We observe four types of publicly imposed disciplines enacted upon idol stars in Korea. First, future releases could be put on hold until a date when the public seems more forgiving. Second, a member could be removed from promotional activities, or even performances, or could continue but with less screen time and fewer lines. Third, a member could be entirely removed from a group (as in the infamous case of Jay Park, once of 2PM). Fourth, idols could be pulled from advertising, acting, and other contracts beyond their musical activities. In each of these cases, the views of the public (beyond just fans) reach the company CEOs and presidents, who are then required to carry out or facilitate these disciplinary actions. These, in turn, are often accompanied by the spectacle of apology, which manifests in the K-pop idol context in three ways: (1) as public apologies ranging from press conferences to videos uploaded by idols, (2) as letters of apology—handwritten letters showing more sincerity than typed messages—and (3) in the least severe cases, as blandly worded statements from agencies with excuses and promises that another incident will not arise.

For idols, there is an ever-present awareness that mistakes, or even failure to please the agency, may have drastic consequences. Aware of this and angered by flaws and perceived missteps, anti-fans and ordinary netizens actively criticize stars, seeming to gain perverse enjoyment from flexing their collective digital muscle. The rapper Tablo, part of the hit group EPIK High, experienced years of attacks from organized groups of “anti-fans,” which eventually led to the suspension of EPIK High and Tablo’s activities, interrupting their momentum to the point that they may never recover their previous popularity. These attacks came from the ranks of the more than 100,000 members of his anti-fan cafes claiming that Tablo could not possibly have completed an MA in English Creative Writing at a school as prestigious as Stanford, despite his having growing up in Canada and having produced his diploma, transcripts, and interviews with former professors (Shim DB 2014, Shin HR 2015). Tablo’s case demonstrates the importance of the artist’s projected image, and the repercussions that can be directly caused by excessive attention to the private aspects of an idols’ life. Ultimately, even baseless claims can have a huge impact on celebrities.

If a K-pop star misbehaves their character is tarnished, and people may believe that they do not deserve their career because of the lack of separation between stage persona and the individual—as show-cased on the near constant stream of non-music media appearances idols are required to make. This high standard makes the lives of celebrities in Korea immensely difficult. The netizens discipline idols, demanding public apologies, official statements, and changed plans on a wide variety of issues. We can observe such behavior in the cancelled collaboration between Monsta X member Jooheon and No:el, a young rapper embroiled in controversy over his politician father.47 It can also be seen in netizens’ savage bullying of transgender star Harisu—they not only claim that she maintains her appearance only through surgery, but they also deliberately flout her chosen gender pronouns. At times, people near gleefully proclaim the end of a career, as when Lee Joon (formerly of MBLAQ) was demoted from active army duty to reservist status due to “panic disorder.” This prompted netizens to point out that he could not possibly continue with his musical or acting career if he truly suffered from panic disorder.48 Netizens, fans or otherwise, seek to control aspects of idols’ lives, and although this can bring about positive results (such as when fans pressure agencies to prepare a release for an idol), it can be downright malicious, such as when netizens demand that stylists take responsibility for perceived poor costume choices for their beloved stars, or when netizens burn Red Velvet merchandise featuring Irene because she read a feminist novel.49

Although a beloved star, Jonghyun had experienced his own share of privacy-invading stories and online attacks. For example, when Jonghyun dated the young actress Shin Se-kyung for several months in 2010 and 2011, the constant spotlight on the couple undoubtedly contributed to the end of the relationship.50 In 2013, Jonghyun was attacked online by Ilbe (a sort of 4chan website equivalent in Korea) for supporting LGBT rights in Korea.51 On other occasions, he was attacked online for what groups saw as a sexist comment on women as his muse, and for standing by his SHINee group mate Onew, who had been accused of sexual harassment after a drunken incident at a nightclub in 2017. While this type of scrutiny is not exclusive to K-pop or Korea, the level of vitriol and pervasiveness of criticism—criticism that may make the front page of newspapers—can contribute to suicide in the entertainment industry. Both celebrities and everyday targets of online harassment have expressed the difficulty of experiencing a stream of criticism from a faceless and anonymous mass. Clearly, a thick skin is required for weathering these attacks, but idols are not really chosen for thick skin. Jonghyun’s suicide note (at the beginning of this article) makes it clear that he had sought professional help and that his problems had not been taken seriously. Idols living in a pressure cooker should be provided with confidentiality-guaranteed, accessible mental health professionals in the same way that personal trainers and vocal coaches are made available.

Every aspect of Jonghyun’s life points to a deeply sensitive perfectionist, searching for unconditional love. Jonghyun’s last song, “Hwansangtong” (“Only One You Need”), purportedly about mourning a loved one, was the second track on his posthumous solo album, Poet | Artist. In it, Jonghyun wrote of a person at the very limits, seeking simple acceptance:

Things that are blindingly beautiful are always that way / Shaking as if it will collapse

Dangerously shining as if it’ll explode / The more nervous you get

Even if your body is ripped apart / I’ll embrace it all.

|

The lead single from Jonghyun’s posthumously released solo album, “Shinin.” |

|

A fan made lyric video for Jonghyun’s “Only One You Need.” |

What does it mean to be the focus of such a concentrated and controlling gaze? The 18th Century thinker Jeremy Bentham introduced the concept of the panopticon, a perfect tool for controlling prison populations, where a single individual could monitor multiple individuals without the latter knowing whether they were under observation or not. This idea of the panopticon, specifically as theorized by Michel Foucault (1977), has long been used in discussions of how the (real or imagined) gaze of others can discipline our actions. Can we talk of celebrities, and particularly idol stars, as being the object of the panopticon? Not really. The panopticon is one observing many, but the observed, the idol star, is actually one being observed by many. The sociologist Thomas Mathiesen specifically addressed the failure in Foucault’s argument to account for modern mass media, and supplemented the panopticon with the term synopticon, explaining: “increasingly the many have been enabled to see the few—to see the VIPs, the reporters, the stars” (1997: 219). In essence, Mathiesen wrote of how the lives of the mediatized famous are a form of social control over the watchers, who are given seductively aspirational points of reference. The synopticon has, in some scholarly disciplines, become the most “prominent way of theorizing the role of the media” (Doyle 2011: 287). The mass media can “conduct surveillance, engender public support for it,” as well as aid resistance to surveillance (2011: 290). Yet, Mathiesen and Doyle’s conceptualizations of the synopticon ultimately focus on what it means for ordinary citizens, falling short of capturing what it means for the objects of that concentrated gaze.

The media and the people accessing that media are constantly exercising surveillance over idols—robbing them of a greater deal of autonomy than that they relinquished in trusting their entertainment agency’s decision makers. Idols cooperate in churning out and broadcasting a constant stream of media products. To survive in the cut-throat industry, they appear on variety programs and reality shows; to make money, they appear in advertisements; and if their performances and other professional media activities are not enough to satisfy their fans, they engage social media in a wide variety of ways, from posting cute photos to uploading footage of themselves playing video games. The media further feeds the desire to feel close to the stars, creating a thirst for the details of idols’ private lives. The public surveillance of sensationalized tidbits, and the obsessive desire to know everything about idol stars are embodied by the sasaeng fan. One of the few academic papers on the subject explains, “Sasaeng fans are identified by a need to seek out their idols’ exact schedules in order to be as close to them as possible, as often as possible” (Williams and Ho 2016: 82). Going beyond buying tickets to fan meetings and attempts to interact further with the idols, the sasaeng fan actually supplants the role of the paparazzi in other countries—paparazzi stalk stars, capturing their private moments for a payout from a media outlet. The same type of news stories, more accurately called “infotainment,” are often generated by sasaeng fans in Korea.

Perhaps calling sasaeng fans ‘fans’ is misleading. In analyzing the Tablo case, Shin Haerin proposes that we discuss the consumption of celebrity life in terms of “spectatorship” (2015: 134). For Shin, fandom implies devotion, and audiences are somewhat removed, but spectators experience “transgressive enjoyment” from consuming scandals and personal details (Ibid.). Clearly, sasaeng fans seek not just transgressive enjoyment, but simultaneously convince themselves they do it in the spirit of love. This motivation allows sasaeng fans, who spend considerable amounts of money and time following and observing idol stars, to claim the title of “fan,” but their extreme actions are vilified by the media and the “good” fans who claim to respect the idols’ privacy. At the same time, the media, the general public, and the “good” fans readily consume the private details revealed by sasaeng, along with the stories of sasaeng fans’ extreme acts, taking on the role of spectators and participants as they rise to the online defense of their idol. In the absence of spectatorship (reading stories with clickbait headlines on sites that mix gossip with reviews of musical releases, or news in the form of statements by entertainment agencies), celebrities could experience privacy. It is a shaky moral position that allows others to pathologize the sasaeng fan for trying to get close to and be acknowledged by the idol, while still consuming celebrity infotainment that violates the privacy of idols. This is underscored by the fact that the industry “structurally condones or even actively promotes voyeurism as a lucrative add-on commodity” (Shin HR 2015: 137). Larry Gross explains that our society has become addicted to media, “our drug of choice is entertainment—then we should not be surprised at our willingness to sacrifice privacy to the intrusions of media we have collectively empowered” (2003: 110).

Worse, while idols are under this non-stop surveillance, instead of being subjected to one set of rules (as in prison), the idol star is subjected to discipline from a fan and non-fan, domestic and foreign public. Members of this public expect perfection in the idols, but may hold vastly different definitions of perfection. Foreign fans new to K-pop are often attracted to K-pop’s cleaner and more picture-perfect image, and therefore as the idols attract new fans they are pushed onto an ever-higher pedestal. Simultaneously the increasingly empowered netizens—fans, anti-fans, and the rest of the population—seem to have lost sight of reasonable limits to their monitoring and disciplining habits. In American pop culture, for example, the private life of celebrities is somewhat separated from their “art.” Although tabloids, paparazzi and “gossip news” entertainment channels like TMZ abound, they target a certain audience that purposely consumes this star gossip. The scandals surrounding stars’ behavior and covered by these media very rarely reach the general public. Justin Bieber, a North American superstar, has amassed a record of legal issues, drug use and behavioral misconducts, including an incident in 2013, where he urinated in a mop bucket behind a New York restaurant, while slandering former American president Bill Clinton.52 Even as these incidents are made public, the impact on Bieber’s career is negligible, as his celebrity does not seem to wane, and he earned his sixth no. 1 album on the Billboard 200 chart in 2015.53

In K-pop, Beiber-esque misdeeds would virtually destroy an artist’s career.54 In the Korean media, idols’ behavior can spark controversies and discussions around their “bad” attitude, which they might be accused of if, for example, they did not seem sufficiently sincere when greeting others, especially “senior” celebrities, on television programs.55 Has an American star ever been castigated in headlines for failing to enthusiastically say hello to another star? Control over stars in this way is made possible precisely by the fact that the Korean spectators are considerably more homogenous than, for example, the North American media consumer, and generally share ideas of performed politeness. Furthermore, in Korea, there is significant inter-generational media consumption—a popular drama may achieve a 20% viewership rate—and K-pop is similarly viewed and listened to by young and old alike (albeit more passively by older generations). Outside Korea, the viewers and producers of a show like Duck Dynasty may have little overlap with the American who objects to Kendall Jenner’s Pepsi ad or Roseanne Barr’s tweets. Those celebrities can do things that cause vocal protests, but maintain a core fan base and find future work. However, the smaller and more tight-knit nature of the Korean media business means that once consensus turns against a star, it can be very hard to find someone willing to offer them a second chance.

|

Jonghyun performing during the January 8th, 2015 Base Showcase. Photo credit: By Sperospera for Jonghyun! (150108 BASE SHOWCASE 종현) [CC BY 4.0 (here)], via Wikimedia Commons. |

Why Jonghyun’s Suicide Is About Much More than One Depressed Pop Star

The entire idol star system works by making the idols, their faces and their presence, into a monetized commercial object that is employed to advertise products (such as Jonghyun’s modeling for Labiotte in 2017). In Korea, more than 60% of all advertisements feature a famous face, and idol stars are among the most often used celebrities. Compared with other countries, the saturation of famous faces is extreme; vis-à-vis Western countries such as Australia (18.2%), Germany (13.9%), and the Netherlands (13.4%), Korea (61.1%) leads in Asia with Japan (49.0%) and Indonesia (26.4%) following behind (Turnbull 2016: 128). Since advertising in general “advances an ideological fantasy that explains the lack in a subject, and in society in general, by the lack of consumption and asserts consuming, and by extension participating in the capitalist economy, as a way to recover the impossible enjoyment” (Fedorenko 2014: 344), idol stars appearing in these ads become “coterminous with consumption” (Galbraith and Karlin 2012: 2). If product placement works—and K-pop videos are increasingly rife with product placement—and if people really ask for plastic surgery to look more like their favorite idols (as clinics claim), it is unreasonable to think that the suicide of an idol suffering from depression would not be grimly (but similarly) effective. Simply, if a fan will buy a product that a star endorses, will they not also choose to emulate the star in more destructive ways?

Suicide grabs headlines— the raw emotion of the one who is gone and those they left behind pull at our heart strings. Youth suicide is particularly chilling as the emotional rollercoaster of our teenage years is relatable. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) the American youth suicide rate nearly doubled between 2007 and 2016. South Korea’s suicide rate has also increased alarmingly in the past 20 years, especially with regard to other OECD countries (Jang et al. 2016; Ji et al. 2014a; Park et al. 2016; Song et al. 2014).56 Cluster suicides related to celebrity suicides may have contributed significantly to this increase (Myung et al. 2015). Cluster suicides fall within the CDC’s list of risk factors, including “history of depression, easy access to lethal means, and exposure to previous suicidal behavior by others.”57 Although the CDC undoubtedly means that cluster suicides impact people who physically reside within the same community, Jonghyun as a globally followed idol star exposed all his fans, to some of whom he surely seemed as close as a member of their own community, to suicide. Worse, Jonghyun’s suicide method is easy to reproduce—he provided an example of easily accessible lethal means to any suicidal person who can seal themselves in a reasonably small room with a stove and charcoal briquettes.

It has been well-established that celebrity suicides often lead to copycat suicides, and a phenomenon called the Werther Effect (Ji et al. 2014a, Myung et al. 2015; Park et al. 2016; Song et al. 2014). Copycat suicides that follow after the suicide of a celebrity and are not locally grouped are called mass clusters, according to the psychological research carried out by Alex Mesoudi (2009). Mesoudi determined that “national suicide rates rise immediately after the suicides of entertainment celebrities” (2009: 1), attributing this behavior to “social learning” (ibid.). Even more disturbing, Mesoudi found the suicide increase was “proportional to the amount of media coverage” (ibid.), making the media circus after Jonghyun’s death dangerous. Part of the importance of Jonghyun’s suicide is that it has the potential not just to elevate national suicide rates, but also, to elevate international suicide rates. In general, the more suicide is reported by the media, the more cluster suicides are induced in the general population (Jang et al. 2016; Lee JS et al 2014; Song et al. 2014). The copycat effect has proven to be more severe when the subject is a public figure (Fu and Chan 2013; Jang et al. 2016; Lee JS et al 2014; Park et al 2016; Song et al. 2014), particularly so when it is an entertainment celebrity (Jang et al. 2016; Myung et al. 2015).

Some studies show that the groups most affected by celebrity suicide tend to be the same age and/or gender as the celebrity (Fu and Chan 2013; Jang et al. 2016; Ji et al. 2014a; Park et al. 2016). Others believe that females or youth are more susceptible to the Werther Effect (Myung et al. 2015; Park et al. 2016). Studies in Korea have shown that after a friend commits suicide, youth suicidal ideation increases significantly (Song et al 2012). While there is some disagreement in the community as to which demographics are affected the most (Ji et al. 2014a), many scholars agree that the greatest correlation occurs in the group of people who use the same suicide method (Lee JS et al. 2014; Myung et al. 2015), which suggests that the cluster suicides that occur after a celebrity suicide are indeed copycat events. Before September 2008, carbon monoxide from charcoal was not a common suicide method in South Korea, but it has become widespread since. This increase is attributed to the suicide of Ahn Jae-Hwan, a celebrity who used this method in 2008 (Ji et al. 2014b). Of the 597 news articles published within the first two days of his death (September 5, 2008), 40% “contained a detailed method used for his suicide. Thirteen (76.5%) of a total of 17 TV video news on the day showed [the] charcoal briquettes [that] were found burned inside his car” (Ji et al. 2014b: 1175). With such information readily available to the public, it is likely that the ensuing increase in carbon monoxide poisoning as a suicide method can be traced back to Ahn’s death. “Risk of CB suicide was 11.69 times higher after September, 2008… compared to the months prior” (Ji et al. 2014b: 1176). Research on this suicide method in Korea has shown that most victims were “young, male, single, highly-educated, urban-based, and [died] between October and December” (Lee AR et al 2014).

Some think that the South Korean population may be more vulnerable to the Werther Effect than that of other countries (Jang et al. 2016). The Korean media violate suicide reporting guidelines more than media in certain other countries (Ji et al. 2014a; Ji et al. 2014b). Moreover, “the credibility and influential power of the media are relatively high in South Korea, and this may have evoked a significant copycat effect. […] Major television networks and newspapers are important players in the cultural scene in South Korea” (Lee JS et al. 2014: 470). According to Nielsen Korea figures from 2008, the year that Ahn Jaehwan committed suicide, the evening news broadcasts of the three major Korean TV networks “usually reaches at least 40% of the population” (Ibid.), a much higher figure than in the US, where ABC, NBC, and CBS news may combine for less than 2% of viewers.

Lee et al. describe two possible theoretical explanations behind celebrity suicide and those they affect: (1) vertical identification (or differential identification theory), in which people copy the behavior of those they look up to and (2) horizontal identification, in which people copy the behavior of those who are similar to themselves (Lee JS et al. 2014: 459). This helps to explain why positive portrayals of a star tend to induce more copycat suicides than negative portrayals. The suicide of rock stars like Kurt Cobain do not provoke the same copycat reaction—everyone knew that Cobain made vibrant music but had problems in his relationship, with being famous, and with substance abuse.

Most sources agree that media portrayal, more than any other factor, is responsible for the increased suicide rate after a celebrity suicide. As in the case of Ahn Jae-Hwan, the South Korean media frequently violates suicide reporting guidelines set by the World Health Organization (WHO), the Korean Association for Suicide Prevention (KASP), and the Journalists Association of Korea (JAK). It was common for stories to detail the method and location of suicides, but not to explain how to recognize the heightened prospect that someone might attempt suicide or what to do if one were to suspect suicidal intentions (Lee JS et al. 2014: 460). Moreover, suicide reporting via social media is unregulated and can also contribute to harmful exposure (Ji et al. 2014a; Park et al. 2016). This makes it particularly important that Jo Min-gi’s death was just “suicide” with no method or details disclosed, and Seo Minwoo, an idol star member of 100% was ” cardiac arrest.”58 Concern about the Werther Effect, and criticism of the press and its reportage on Jonghyun may have caused this change in reporting.

In this article, we have tried to convey the importance of Jonghyun’s suicide, with particular attention to how it reflects the stresses and lived reality of Korean society, as well as how it is connected to the social disciplining of idol stars, and the serious risk of copycat suicide. It remains to be seen what Jonghyun’s legacy will be.59 By sending his suicide note to a friend, online, and asking her to distribute it after his death, Jonghyun forced all of us to look at this issue. His death by his own hand could not be concealed, and this has forced fans, activists, and those with political power to (re)consider this serious social issue and how to effect change in society. At a cabinet meeting in January 2018, the Korean government finalized comprehensive measures to decrease the suicide rate.60 The 70,000 cases of suicide from the past five years will be analyzed, and 1 million health professionals will receive training to assist those suffering from depression. Finally, mandatory national health examinations will include tests for depression from 2018 onwards. It is the hope of this paper’s authors that Jonghyun’s legacy will be as improved and de-stigmatized mental health care measures, reinforcement of emergency services such as suicide hotlines, and an increased sensitivity to the role of the public’s spectatorship in generating insurmountable pressure on idols.

끝

|

Jonghyun singing in Taiwan, May 11th, 2014 (SHINee World Concert III). Photo credit: By Sparking (140511 SWC3 in Taiwan Jjong) [CC BY 4.0 (here)], via Wikimedia Commons.] |

Related articles

Joanna Elfving-Hwang. “Cosmetic Surgery and Embodying the Moral Self in South Korean Popular Makeover Culture.” Asia-Pacific Journal 11, no. 24 (2013): 1-16

Stephen Epstein and Rachael Miyung Joo. “Multiple Exposures: Korean Bodies and the Transnational Imagination.” Asia-Pacific Journal 10, no. 33 (August 13, 2012): 1-17

Nissim Kadosh Otmazgin. “A New Cultural Geography of East Asia: Imagining a ‘Region’ through Popular Culture.” Asia-Pacific Journal 14, no. 7 (2016): 1-12

Sources

Bae, Sang-hoon and Ji-Hoon Song. “Youth Unemployment and the Role of Career and Technical Education: A Study of the Korean Labor Market.” Career and Technical Education Research 31, no. 1 (2006): 2-21.

Cho, Dong-hyun and Hyeok-yong Kwon. “Mueosi han’gugineul bulhaengage mandeuneun’ga? Sodeuk bulpyeongdeung, gihoe bulpyeongdeung, geurigo haengbokui gyunyeolgujo [What Makes Koreans Unhappy?: Income Inequality, Inequality in Opportunities, and Social Cleavages of Happiness].” Gyeonghui daehakgyo illyusahoe jaegeon yeonguwon [Kyunghee University Center for the Reconstruction of Human Society] 31, no. 1 (2016): 5-39.

Chua, Beng Huat. “Conceptualizing an East Asian Popular Culture.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 5, no. 2 (2004): 200-22.

Doyle, Aaron. “Revisiting the Synopticon: Reconsidering Mathiesen’s ‘the Viewer Society’ in the Age of Web 2.0.” Theoretical Criminology 15, no. 3 (2011): 283-99.

Drapalski, Amy L, Alicia Lucksted, Paul B Perrin, Jennifer M Aakre, Clayton H Brown, Bruce R DeForge, and Jennifer E Boyd. “A Model of Internalized Stigma and Its Effects on People with Mental Illness.” Psychiatric Services 64, no. 3 (2013): 264-69.

Elfving-Hwang, Joanna. “Cosmetic Surgery and Embodying the Moral Self in South Korean Popular Makeover Culture.” Asia-Pacific Journal 11, no. 24 (2013): 1-16.

Elfving-Hwang, Joanna. “K-Pop Idols, Artificial Beauty and Affective Fan Relationships in South Korea.” In Routledge Handbook of Celebrity Studies, edited by Anthony Elliott. 190-201. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Epstein, Stephen, and Rachael Miyung Joo. “Multiple Exposures: Korean Bodies and the Transnational Imagination.” Asia-Pacific Journal 10, no. 33 (August 13, 2012): 1-17.

Epstein, Stephen. “‘Into the New World’: Girls’ Generation from the Local to the Global.” In K-Pop: The International Rise of the Korean Music Industry, edited by Jungbong Choi and Roald Maliangkay. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Random House, 1977.

Fu, King-wa, and CH Chan. “A Study of the Impact of Thirteen Celebrity Suicides on Subsequent Suicide Rates in South Korea from 2005 to 2009.” In PLoS ONE 8, no. 1 (2013).

Fuhr, Michael. Globalization and Popular Music in South Korea: Sounding out K-Pop. London: Routledge, 2015.

Galbraith, Patrick W., and Jason G. Karlin. “Introduction: The Mirror of Idols and Celebrity.” In Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture, edited by Patrick W. Galbraith and Jason G. Karlin. 1-32. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Gibson, Margaret. “Some Thoughts on Celebrity Deaths: Steve Irwin and the Issue of Public Mourning.” Mortality 12, no. 1 (2007): 1-3.

Gross, Larry. “Privacy and Spectacle: The Reversible Panopticon and Media-Saturated Society.” In Image Ethics in the Digital Age, edited by Larry Gross, John Stuart Katz and Jay Ruby. 95-114. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Ho, Swee-Lin. “Fuel for South Korea’s “Global Dreams Factory”: The Desires of Parents Whose Children Dream of Becoming K-Pop Stars.” Korea Observer 43, no. 3 (2012): 471-502.

Inglis, Fred. A Short History of Celebrity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Jang, Sooah, Minsung Ji, Jinyoung Park, and Wootaek Jeon. “Copycat Suicide Induced by Entertainment Celebrity Suicides in South Korea.” Psychiatry Investigation 13, no. 1 (2016): 74-81.

Jeong, Baekgeun and Gerry Veenstra. “The Intergenerational Production of Depression in South Korea: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study.” International Journal for Equity in Health 16, no. 13 (2017): 1-8.

Jeong, Seunghwa. “1950-60nyeondae Han’guksaehoe gyeongjegujo byeonhwawa gajokdongbanjasal [Changes to the Economic Structure of Korean Society and Whole Family Suicide, 1950-60].” Naeileul yeo-neun yeoksa [The History of Tomorrow] 42, no. 3 (2011): 180-200.

Jeong, Sooim, B.C. Ben Park, and Kathryn Strother Ratcliff. “Cultural Stigma Manifested in Official Suicide Death in South Korea.” Omega–Journal of Death and Dying 0, no. 0 (2016): 1-18.

Ji, Namju, Yeon-pyo Hong, Steven John Stack, and Won-Young Lee. “Trends and Risk Factors of the Epidemic of Charcoal Burning Suicide in a Recent Decade among Korean People.” Journal of Korean Medical Science 29, no. 8 (2014): 1174-77.

Ji, Namju, Weon-Young Lee, Maengseok Noh, and Paul S.F. Yip. “The Impact of Indiscriminate Media Coverage of a Celebrity Suicide on a Society with a High Suicide Rate: Epidemiological Findings on Copycat Suicides from South Korea.” Journal of Affective Disorders 156, no. 56-61 (2014).

Jo, Jungin. “Weapons of the Dissatisfied? Perceptions of Socioeconomic Inequality, Redistributive Preference, and Political Protest: Evidence from South Korea.” International Area Studies Review 19, no. 4 (2016): 285-300.

Ki, Myung, Jong-woo Paik, Kyeong-sook Choi, Seung-ho Ryu, Changsu Han, Kangjoon Lee, Byungjoo Ham, et al. “Delays in Depression Treatment among Korean Population.” Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 6, no. 4 (2014): 414-24.

Kim, Doohwan and Yool Choi. “The Irony of the Unchecked Growth of Higher Education in South Korea: Crystallization of Class Cleavages and Intensifying Status Competition.” Development and Society 44, no. 3 (2015): 435-63.

Kim, Hyejin. “‘Spoon Theory’ and the Fall of a Populist Princess in Seoul.” Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 4 (2017): 839-49.

Kim, Jungwoo, Heeyoung Jung, Doyeon Won, Jaehyun Noh, Yongseok Shin, and Taein Kang. “Suicide Trends According to Age, Gender, and Marital Status in South Korea.” Omega–Journal of Death and Dying 0, no. 0 (2017): 1-16.

Kim, Moon-Doo, Seung-Chul Hong, Sang-Yi Lee, Young-Sook Kwak, Chang-In Lee, Seung-wook Hwang, Tae-Kyun Shin, Seung-Min Lee, and Ji-Nam Shin. “Suicide Risk in Relation to Social Class: A National Register-Based Study of Adult Suicides in Korea, 1999–2001.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 52, no. 2 (2006): 138-51.

Kim, Sujeong, and Sooah Kim. “‘Jipdanjeok dodeokjuui’ etoseu: Honjongjeok keipapui han’gukjeok munhwa jeongcheseong [The Ethos of Collective Moralism: The Korean Cultural Identity of K-Pop].” Eonrongwa sahoe [Media and Society] 23, no. 3 (2015): 5-52.

Lee, Ah-Rong, Myunghee Ahn, Taeyeop Lee, Subin Park, and Jinpyo Hong. “Rapid Spread of Suicide by Charcoal Burning from 2007 to 2011 in Korea.” Psychiatry Research 219 (2014): 518-24.

Lee, Hyojung, Youngjun Ju, and Eun-cheol Park. “Utilization of Professional Mental Health Services According to Recognition Rate of Mental Health Centers.” Psychiatry Research 250, no. April (2017): 204-09.

Lee, Jesuk, Weon-Young Lee, Jang-Sun Hwang, and Steven John Stack. “To What Extent Does the Reporting Behavior of the Media Regarding a Celebrity Suicide Influence Subsequent Suicides in South Korea?” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 44, no. 4 (2014): 457-72.

Lee, Seung-yeon, Jun-sung Hong, and Dorothy Espelage. “An Ecological Understanding of Youth Suicide in South Korea.” School Psychology International 31, no. 5 (2010): 531-46.

Maliangkay, Roald. “Uniformity and Nonconformity: The Packaging of Korean Girl Groups.” In Hallyu 2.0: The Korean Wave in the Age of Social Media, edited by Sangjoon Lee and Abe Markus Nornes. 90-107. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015.

Marshall, P. David. Celebrity and Power: Fame in Contemporary Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Mathiesen, Thomas. “The Viewer Society: Michel Foucault’s ‘Panopticon’ Revisited.” Theoretical Criminology 1, no. 2 (1997): 215-34.

Mesoudi, Alex. “The Cultural Dynamics of Copycat Suicide.” PLoS ONE 4, no. 9 (2009): 1-9.

Mole, Tom. “Hypertrophic Celebrity.” In M/C Journal 7, no. 5 (2004).

Myung, Woojae, Hong-Hee Won, Maurizio Fava, David Mischoulon, Albert Yeung, Dongsoo Lee, Dohkwan Kim, and Hongjin Jeon. “Celebrity Suicides and Their Differential Influence on Suicides in the General Population: A National Population-Based Study in Korea.” Psychiatry Investigation 12, no. 2 (2015): 204-11.

Otmazgin, Nissim Kadosh. “A New Cultural Geography of East Asia: Imagining a ‘Region’ through Popular Culture.” Asia-Pacific Journal 14, no. 7 (2016): 1-12.

Park, Juhyun, Nari Choi, Seogju Kim, Soohyun Kim, Hyonggin An, Heon-jeong Lee, and Yujin Lee. “The Impact of Celebrity Suicide on Subsequent Suicide Rates in The General Population of Korea from 1990 to 2010.” Journal of Korean Medical Science 31, no. 4 (2016): 598-603.

Pescosolido, Bernice A, Tait R. Medina, Jack Martin, and J. Scott Long. “The ‘Backbone of Stigma:’ Identifying the Global Core of Public Prejudice Associated with Mental Illness.” American Journal of Public Health 103, no. 5 (2013): 853-60.

Roh, Sungwon , Sang-uk Lee, Minah Soh, Vin Ryu, Hyunjin Kim, Jungwon Jang, Heeyoung Lim, et al. “Mental Health Services and R&D in South Korea.” International Journal of Mental Health Systems 10, no. 45 (2016): 1-10.

Shim, Doobo. “The Cyber Bullying of Pop Star Tablo and South Korean Society: Hegemonic Discourses on Educational Background and Military Service.” Acta Koreana 17, no. 1 (2014): 479-504.

Shin, Haerin. “The Dynamics of K-Pop Spectatorship: The Tablo Witch-Hunt and Its Double-Edged Sword of Enjoyment.” In K-Pop: The International Rise of the Korean Music Industry, edited by JungBong Choi and Roald Maliangkay. 133-45. New York: Routledge, 2015.