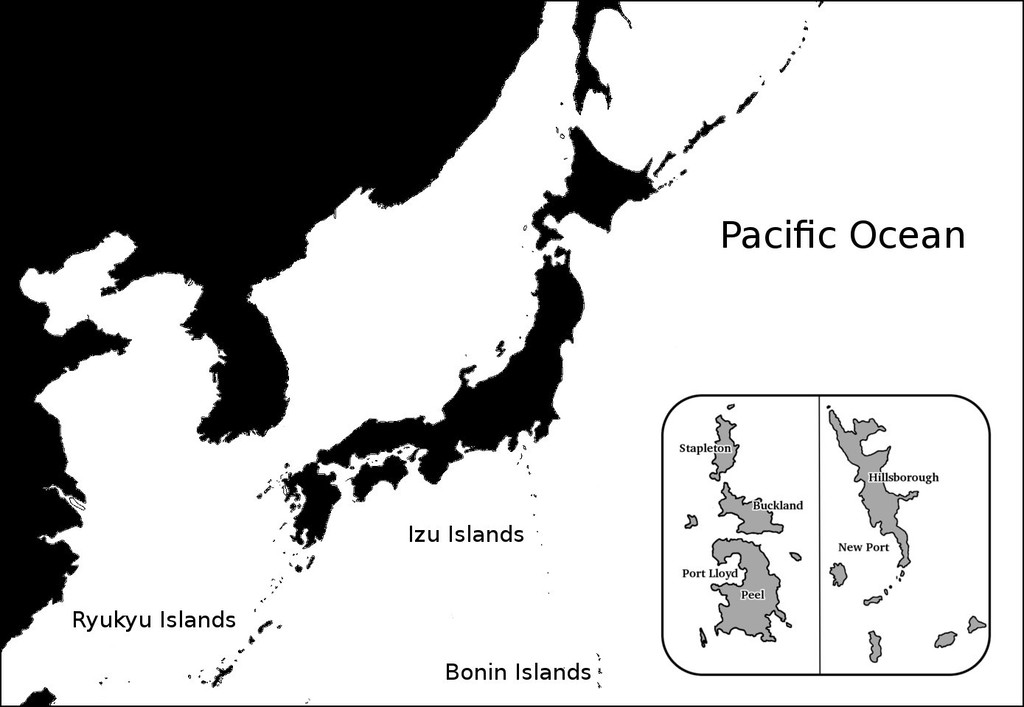

Abstract: In 1830 a group of pioneers from Hawaii settled the uninhabited Bonin Islands (Ogasawara Guntō), located about 1,000 km south of Edo (present-day Tokyo) where their descendants formed their own cultural identity. This article explores some of the challenges the Bonin Islanders have faced since the Japanese takeover in the late 1870s. An emphasis is placed on their struggles with a fabricated history that continues to define their relationship with the Japanese state.

Keywords: Bonin Islands, Ogasawara Islands, ōbeikei, kikajin

Maritime powers in the nineteenth century conquered, seized, annexed, and bought Pacific empires. Few islands escaped their grasp. Even fewer still remained to be conquered. Divided according to the logic of imperial rivalries, Oceania was pulled piece by piece into regional and global schemes. Gunboat captains and civilian sailors alike planted their country’s flag with patriotic zeal on remote shores in far-flung latitudes. Native sovereignty largely went ignored and, at times, so too did prior claims made by other great nations. As adventurers painted the globe in their national colors, overlapping ambitions led to conflicts that demanded resolution through bloodshed or diplomacy. The Pacific Ocean offered opportunities for rising powers to gain political leverage and promised established powers a way to cling to the status quo. It is in this context that the British Empire, United States, and Japan all laid claim to the Bonin Islands or, as they are known in Japan, Ogasawara Guntō (Ogasawara Islands).

These three countries and numerous imperial dreams competed for sovereignty. British merchants envisioned Peel Island—the largest of the Bonins—as a thriving hub in the growing transpacific trade, while some of their hawkish countrymen contemplated turning it into an island fortress from which to dominate the region.1 True believers marked it as a potential beachhead for the Christianization of East Asia.2 Economic patriots in the United States lobbied their government to develop Peel Island’s principal anchorage, Port Lloyd, into a way station for cargo-carrying steamships and a resupply depot for blubber hunters combing the whale-rich waters surrounding the Bonins. Americans also imagined the islands as a hub in the burgeoning mail steamer network designed to increase global communications. The advantages of maintaining a naval base at the crossroads of the western Pacific was not lost on American military strategists either.3 Japanese bureaucrats proposed sending agricultural colonists to the tropical and subtropical Bonins, where they could grow out-of-season produce and gather medicinal herbs to lessen their country’s reliance on foreign suppliers.4 An intellectual named Watanabe Kazan thought the islands could host meaningful West-East exchange.5 Japanese scholars declined to voice support for his idea, perhaps because in 1841 the government silenced Watanabe by obliging him to commit ritual suicide.6 The Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1867) and subsequent Meiji regime (1867-1912) had other plans.

In 1876, Japan bested its rivals in the decades-long territorial dispute over the Bonins by invoking a fabricated history that claimed a Japanese samurai-explorer named Ogasawara Sadayori had taken possession of the islands in 1593.7 This narrative was accepted internationally, but in point of fact, Japan had little contact with the Bonins before making territorial claims; however, more on this anon. Japan’s victory produced three immediate rewards: (1) authority to deny foreign powers a safe harbor uncomfortably close to the Japanese mainland, (2) license to redraw political boundaries in the western Pacific that preemptively thwarted challenges to Japanese rule in the southern Izu Islands (located between Japan proper and the Bonins), and (3) a pretext to occupy a strategic foothold in Oceania. The far-reaching implications of this moment in history were not fully appreciated, even by the Japanese statesmen most responsible for their country’s diplomatic achievement.

Japan’s victory was not absolute. To avoid the ire of the Anglo-American powers over humanitarian concerns, Japanese officials agreed to recognize certain rights—such as land tenure—of the archipelago’s inhabitants, a unique people who owed their existence to colonialism but in many respects stood apart from it. Without much hyperbole it may be claimed that each of the aforementioned imperial dreams seeded the Bonins with settlers. This article is a brief overview of the formation of the Bonin Islanders as a distinct people and details a few of the challenges they have faced since the Japanese takeover in the late 1870s. An emphasis is placed on their struggles with a modern myth (a fabricated history) that continues to define their relationship with the Japanese state. This article also addresses their role as original inhabitants who lack recognition as ‘first peoples’ (also called indigenous peoples, aboriginal peoples, and native peoples).

The original Bonin Islanders

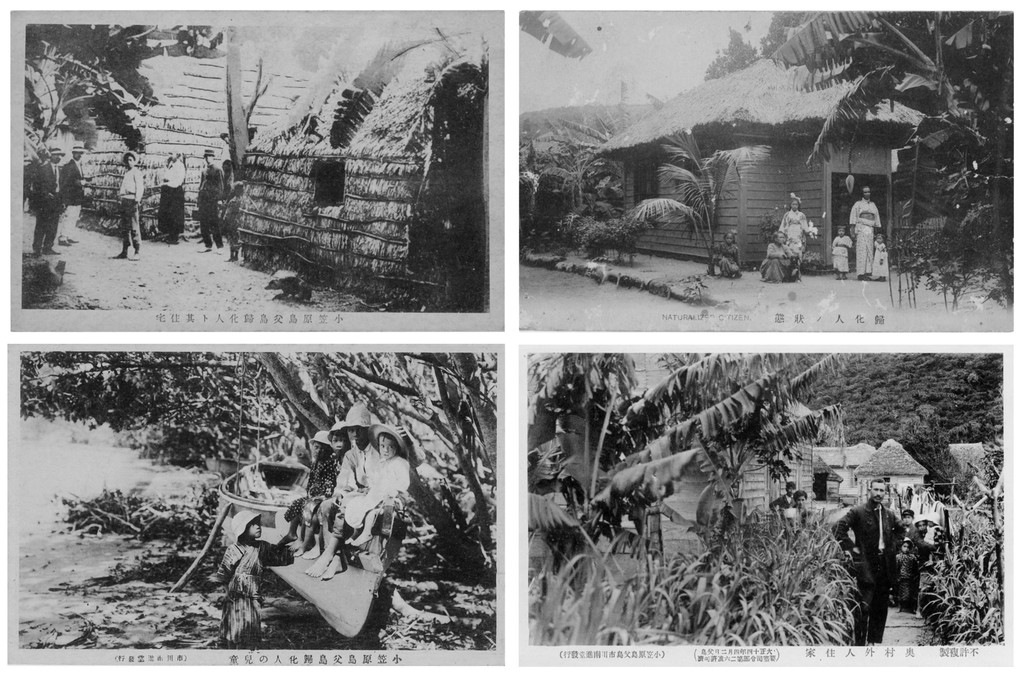

Prior to the 1830 arrival of pioneers from Honolulu, the Bonin Islands were uninhabited despite their idyllic weather and natural resources. These people had been drawn to the Bonins by news of an archipelago untouched by civilization: and that is exactly what they found. They consisted of a dozen or more Hawaiians and five Caucasian males from four different countries. Many aspects of daily life were imported from Hawaii, including material culture and tastes in clothing, handicrafts, and cookery. The locals lived in huts of Hawaiian design and spent many of their waking hours in Hawaiian-style outrigger canoes. They established themselves and began trading with visitors. The Bonin Islands became an important stopping place for whalers in need of solid ground and fresh supplies. The islanders worked as local pilots who helped visiting ships find safe anchorage. They were part time agriculturalists who sold their harvests to sailors and accompanied hunting parties as guides. They also made a living by fishing and turtling. Hawaiian customs and language held sway for the first decade or two.8 English was always the language of commerce, but eventually it became dominant in homes as well.

The original pioneers had received help from Richard Charlton, the first British consul to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), appointed in 1829, to relocate to the Bonins. Charlton never received official permission or support from his government for the venture, but he hoped that someday his fellow Britons would come to recognize the strategic importance of the islands and properly develop the archipelago for king and country.9 British interest did not materialize as Charlton had hoped, leaving the Bonin Islands to function as an independent settlement. This arrangement suited most of the islanders just fine. Over time, the population grew slowly by adding sailors from many nations and various stocks to its ranks.10 The children born on the islands were the consequence of interracial unions. According to one European observer, “[m]iscegenation has brought about rather curious results. In the male children the white parentage is very distinct… in the females the Micronesian blood is unmistakeable… in some cases the women are in appearance very closely akin to the Hindostanee.”11 These “mongrel offspring” or “half-castes,” as they have been called, have even left a small mark upon the English language lexicon.12 In the Oxford English Dictionary a sentence illustrating the term ‘half-white’ reads, “In this boat’s crew…was Charlie Diamond… He was a Bonin island half-white and is well known to old time sealers.”13 Continued miscegenation produced yet more distinct results. Their mixed features became accompanied by mixed feelings towards far off authorities. With time and autonomy, they became a unique people with their own cultural identity.

In the late-nineteenth century, the geopolitics of the western Pacific began to shift. The Bonin Islanders’ days as an independent people were numbered, for powerful nations had plans for their small corner of the world. This eventually led to a three-way sovereignty dispute between the British Empire, United States, and Japan. This is when the Ogasawara Sadayori legend arrived on the shores of the Bonin Islands.

Origins of the Ogasawara Sadayori legend

Europeans encountered and mapped the Bonin Islands first. A Spanish explorer discovered them in 1543.14 More Iberians, according to cartographic evidence, reached these remote shores over the course of the following centuries. In the late 1630s, a Dutch expedition happened upon the Bonins while searching for the fabled Rica de Oro and Rica de Plata (gold and silver) islands.15 A Japanese boat laden with oranges was forced to the Bonins by a storm in 1670, its seven occupants became the first Japanese to see or step foot on any of the islands. These merchant-seamen returned home with a story about an uninhabited archipelago where strange animals haunted alien forests. The Tokugawa Shogunate dispatched a navigator named Shimaya Ichizaemon to investigate the heretofore unknown islands. After spending several weeks there, Shimaya wrote a report that confirmed the details of the 1670 account. He also brought back exotic plants and animals to show his masters in Edo (present-day Tokyo). The men of this expedition called the islands Munin-shima or Uninhabited Islands.16 The Bonins were seen as alien and deemed to lie outside the boundaries of the realm by the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate. Traveling overseas was a crime potentially punishable by death during kaikin (a period that extended from the 1630s to the 1850s), so few Japanese attempted going to the Bonins before the mid-nineteenth century.

News of Shimaya’s 1675 expedition reached the ears of a charlatan who started a persistent rumor that his ancestor, a samurai-explorer named Ogasawara Sadayori, made the discovery decades earlier in 1593. He also claimed that his family held the islands as a fief until they lost contact when the shogunate prohibited overseas travel. Officials investigated the matter. What they found was a down-on-their-luck family that had grown desperate. The government dismissed their petition to develop the islands.17 The public, however, willingly accepted the petition’s contents as true. The legend of Ogasawara Sadayori was born with this fraudulent claim. Genuine information about the Bonins inspired rumors and fanciful tales that over time became intertwined with one another. Put simply, within a few short decades the real events became confused with fictional accounts to all but a few.

In 1786, the military scholar Hayashi Shihei breathed new life into the Ogasawara legend with his book Illustrated Survey of Three Countries, wherein he urged the government to develop the Bonin Islands for economic and geopolitical reasons. The shogunate denounced Hayashi’s writings as criminally inaccurate and placed his works on the index of prohibited reading. He died under house arrest in 1793.18 Illustrated Survey of Three Countries nevertheless enjoyed considerable success, for although it was no longer being printed, individuals made illicit hand-written copies to fill demand.19 In 1832, Julius Klaproth published a French translation of Hayashi’s banned book.20 The details are too complex to explain here, but suffice it to say Japan won the three-way sovereignty dispute over the Bonin Islands by embracing its neglected son Hayashi Shihei. The scholar’s banned book Illustrated Survey of Three Countries was presented as evidence of Japanese sovereignty. Western countries yielded to Japanese claims because Klaproth’s translation convinced their diplomats that Ogasawara Sadayori was a bona fide historical figure.21 In short, Japanese officials knowingly presented a false history to bolster their sovereignty claims. Hayashi was quickly recast as a respected scholar and loyal patriot in Japan. His works were eventually made orthodoxy, and monuments dedicated to him followed. Despite having never existed, Ogasawara Sadayori became an officially celebrated historical figure. He too inspired monument builders.

The Japanese takeover

The thirty small islands of the Bonin archipelago, with Japan’s 1876 diplomatic victory, were conceptually torn from the Pacific and grafted onto the Asiatic fringe. Up until that point, most cartographers, pilot guide compilers, naturalists, and others in the Western world placed the Bonins firmly in Oceania (Oceanica) and often within Polynesia or Micronesia.22 Japanese had also viewed the territory as distinctly non-Asian. In the years following Japan’s takeover, short memories and embellishments to the Ogasawara legend served to distance the archipelago from its Pacific roots. The Ogasawara legend permitted Japanese to view Bonin Islanders as the descendants of foreign squatters instead of a people entitled to indigenous status. An early plan called for their expulsion. A less harsh alternative prevailed, which extended naturalization to the islanders.23 Being classified as naturalized citizens/subjects (kikajin), however, denied them their proper status within Bonin history and put their descendants at a disadvantage when dealing with the Japanese state.

Kikajin implies a courtesy granted by the government to an individual or individuals. For example, a foreign-born refugee holding a Japanese passport is a kikajin. More accurate terms in the Japanese language exist but have not been extended in any meaningful way to the original Bonin Islanders and their progeny, such as senjūmin (original inhabitants), genjūmin (original people), and dochakumin (people of the soil).24 Their descendants for generations were called kikajin and gaijin (foreigners) despite being born as Japanese citizens/subjects. The first inhabitants of the Bonin Islands have never been considered first peoples by the government of Japan.

The Cold War years (1945-1968)

In the early twentieth century, the Bonin Islanders clung to their cultural identity despite being significantly outnumbered by their Japanese neighbors. In doing so, they defied the predictions of would-be-demographers who anticipated their complete assimilation.25 The collapse of the Japanese Empire at the end of World War Two (1945) ushered in a period of profound change that offered opportunities and hazards for the descendants of the original islanders. The United States Navy administered the Bonins for more than two decades (from the post-WWII period up until 1968), while it used Port Lloyd as a Cold War-era naval base.26 This occupation of the Bonins was depicted by Samuel Jameson of the Chicago Tribune as “an attempt by the navy to set up its own little empire under the pretext of maintaining a base vital to free world security in the far east [sic].”27 Descendants of the original inhabitants were permitted to reside on the islands during these years while families considered to be ethnically Japanese were not. This policy of exclusion was viewed by observers in Japan as a case of racial discrimination.28

For many islanders sharing the Bonins with the U.S. Navy in the postwar era was preferable to welcoming back the Japanese government. In the 1950s, a group of them petitioned the U.S. government “to establish the Bonin Islands as a United States affiliate in any capacity which may be considered suitable for the protections of these islands.”29 The petition was instigated, at least in part, by Commander Bronson who may have been a student of history because this proposed arrangement bears resemblance to the “Colony of Peel Island” plan advocated by Commodore Perry in the 1850s.30 The petition upset “Japanese families” who wanted to return home to the Bonins.31 While the idea of turning the Bonins into an American affiliate met with enthusiasm in some circles, Washington policymakers refused to strip Japan of its sovereignty. Instead, in 1970, the United States offered the islanders a pathway to U.S. citizenship for those who had not already obtained it through marriage or military service.32 This further fragmented the small population. The convoluted politics of the era led the islanders to be increasingly called and defined as ōbeikei (people of American and European descent), a term that ignores their Pacific island roots entirely. Following the reversion of the Bonin Islands to Japan in 1968, former residents of Japanese descent returned to find their homes destroyed and lands occupied by islanders.33 The circumstance created by the war and subsequent American occupation unfolded in such a way that the “ōbeikei” once again would be negatively viewed as squatters on Japanese land. History repeated itself.

Life on the Bonin Islands today

The population of roughly 2,500 men, women, and children is confined to a few settlements on the archipelago’s principal islands of Peel (Chichijima) and Hillsborough (Hahajima). Japanese newcomers with no pre-reversion association with the islands now form the majority of the population at about 75 percent. Many are short-term residents who will likely leave the islands by intent or circumstance within a few short years. Kyutomin (old islanders) are about 16 percent of the population. Locals speak of a sannen no kabe (three year barrier), which describes the phenomenon of newcomers as they watch their lofty island dreams crash against the realities of island living. For most people this happens within three years.34 In 2014, approximately 14 percent of residents relocated off the islands. An almost equal number of new arrivals came that year to replace them.35 High turnover is a normal part of Bonin life. Tokyo does not provide relevant statistics on race or ethnicity, but scholars estimate that less than ten percent of the population is descended from the original islanders.36 Japanese with pre-World War II ties comprise the rest of the population at about 16 percent.37 Although the government shies away from highlighting the distinctions between inhabitants, shintōmin (new islanders), kyūtōmin (old islanders), and ōbeikei are terms in common parlance.38 There is some tension between these groups as well as periodic bouts of fatigue from dealing with the 18,000 tourists that visit per year, but disputes seldom escalate into disturbances as cooler heads usually prevail.39 Increased contact and intermarriage blurs the distinction between these groups with each successive generation.

The people of the Bonin Islands enjoy a relatively high standard of living as the Tokyo government ensures that their material needs are met and their access to basic health care is adequate. Moreover, residents enjoy the same legal protections found elsewhere in Japan. Children receive public schooling that meets the standards of Japan’s compulsory educational system, and some of their parents are gainfully employed by municipal, prefectural, and national government offices present in the islands. Quality of life on the Bonins is arguably superior to that in many other parts of Tokyo. Beautiful beaches, clean air, and rural charm are all enhanced by a functioning infrastructure and access to modern conveniences. However, for the descendants of the original Bonin Islanders this comes at a cost.

They are outnumbered. Their culture is slowly being pushed to the margins of society. Demographic trends, Japanese sensibilities, and official policy all contribute to the situation. Whether or not it still is commonly believed, the Ogasawara Sadayori legend continues to cast a shadow over local affairs shaping how the Bonin Islanders are viewed. Here we can blame a sort of cultural inertia. Stated differently, the legend established a cultural frame of reference that affected subsequent events. In 2012, vice mayor of the islands Ishida Kazuhiko stated that no efforts were being made to preserve the non-Japanese culture of the Bonins since it is not a recognized legacy of an indigenous people.40 Other elected officials and bureaucrats have more or less said the same thing. This stance means that the Bonin Islanders are not entitled to special services, nor is the government obligated to provide assistance or fund cultural preservation projects. There is a general sense of pessimism among the descendants of original islanders that elements of non-Japanese culture will endure longer than a generation or two. There are no signs of a cultural reawakening on the horizon to reverse this trend. “All that can be done now,” one interviewee lamented, “is to chronicle what remains of a culture before it disappears.”41 These people are not targeted by their Japanese neighbors or local government for mistreatment. Rather, they are treated fairly as individuals today, but their collective needs as a unique people have been ignored for generations.

Final note

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government oversaw the erection of a monument in 1993 that, according to its accompanying text, commemorates the four-hundredth anniversary of Ogasawara Sadayori’s discovery in 1593. This monument is located on the same property where the Ogasawara Shrine overlooks Port Lloyd. A retired superintendent of the local board of education, that same year, authored a history book that presented the Ogasawara Sadayori narrative as history rather than legend.42 Official views have changed somewhat since the 1990s, but there remains a reluctance to disabuse people of their belief in the Ogasawara legend as is evidenced by recent government publications.

The pioneers who settled the Bonin Islands were not people of American and European descent seeking to make homes for themselves in East Asia, as the Ogasawara legend and term ōbeikei would suggest when presented together. Instead they were people of predominantly Polynesian stock who brought their civilization to another Pacific island, where their children and their children’s children became a unique people partially through interracial unions and frequent cross-cultural exchange during the nineteenth century. The birth of a distinct ethnic identity on the Bonins bears some resemblance to the history of the multiracial Melungeon and Redbone peoples of North America as well as the inhabitants of the Pitcairn Islands in the South Pacific. The living descendants of the original Bonin Islanders present definitional challenges to the terms indigenous peoples, native peoples, aboriginal peoples, and first peoples, while also demonstrating these terms are not entirely synonymous. Through the lens of a modern Japanese myth, the roles of the colonizer and colonized become inverted in the Bonin Islands: the ‘first peoples’ are seen as latecomers and the Japanese colonizers are viewed as natives.

Related articles

- Ryota Nishino, “Pacific Islanders Experience the Pacific War: Informants as Historians and Story Tellers,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol 15, issue 20, no. 2, Oct 12, 2017

- Ilan Kelman, “Disaster Risk Governance for Pacific Island Communities,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol 13, issue 30 no.1, Dec. 14, 2015

- David Chapman, “Inventing Subjects and Sovereignty: Early History of the First Settlers of the Bonin (Ogasawara) Islands,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol 7, issue 24, no. 1, June 15, 2009

- Nanyan Guo, “Environmental Culture and World Heritage in Pacific Japan: Saving the Ogasawara islands,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol 7, issue 17, no. 3, April 12, 2009

Notes

- Thomas Horton James, The Sandwich and Bonin Islands: A Letter to a Noble Lord, on the Importance of Settling the Sandwich and Bonin Islands, in the North Pacific Ocean, on the Plan of a Proprietary Government (London: W. Tew, 1832), 9; William G. Beasley, Great Britain and the Opening of Japan 1834-1858 (London: Luzac & Company, Ltd., 1951), 10-21.

- G. Tradescant Lay, Trade with China: A Letter Addressed to the British Public on Some of the Advantages that would Result from an Occupation of the Bonin Islands (London: Royston & Brown, 1837), 10-13.

- Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the United States Navy was an advocate for turning the Bonins into an American colony for all of the above stated reasons and more, see Matthew Calbraith Perry, A Paper by Commodore M.C. Perry, U.S.N., Read before the American Geographical and Statistical Society, at a Meeting Held March 6th, 1856 (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1856).

- Sakata Morotō, Ogasawaratō kiji vol. 4 (unpublished collection of documents, 1874); Ōkuma Ryōichi, Rekishi no kataru Ogasawaratō (Tokyo: Ogasawara Kyōkai, 1966), 21.

- Tanaka Hiroyuki, ‘Bansha no goku’ no subete (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2011), 241-243.

- Ibid., 110.

- Inamura Hiromoto, “Ogasawaratō ni okeru shiseki oyobi enkaku, 1” Rekishi chiri, vol. 48 no.2 (1926): 18.

- Scott Kramer and Hanae Kurihara Kramer, “The Other Islands of Aloha,” The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 47 (2013): 1-3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Russell Robertson, “The Bonin Islands,” Transaction of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 4 (1876): 132.

- This term was used by Commodore Matthew C. Perry and others to describe a Bonin Islander of mixed ancestry.

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., s.v. “half-white.”

- Bernhard Welsch, “Was Marcus Island Discovered by Bernardo de la Torre in 1543?” Journal of Pacific History, vol. 39, no. 1 (2004): 117.

- Hyman Kublin, “The Discovery of the Bonin Islands: A Reexamination,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. XLIII, no. 1 (1953): 39-40.

- Tabata Michio, Ogasawaratō yukari no hitobito (Tokyo: Bunken Shuppan, 1993), 21-33.

- Isomura Teikichi, Ogasawaratō yōran (Tokyo: Ben’ekisha, 1888), 17-18.

- Yamagishi Tokuhei and Sano Masami, eds., Hayashi Shihei zenshū (Tokyo: Daiichi Shobō, 1980), 5: 411-413.

- Peter Kornicki, The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001), 104.

- Rinsifée, San kokf tsou ran to sets, ou aperçu général des trois royaumes, trans. Julius Klaproth (Paris: The Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland, 1832).

- Tabohashi Kiyoshi, “Ogasawara shotō no kaishū,” Rekishi chiri, vol. 39, no. 5 (1922): 28.

- This point is perhaps best expressed through period maps, such as Henri Duval, Atlas universel d’histoire et de geographie anciennes et modernes, Paris: L. Houbloup, 1835; Conrad Malte-Brun, Atlas complet du precis de la geographie universelle, Paris: Amie Andre, 1837; and Samuel Augustus Mitchell, A New Universal Atlas Containing Maps of the Various Empires, Kingdoms, States and Republics of the World, Philadelphia: Cowperthwait, Desilver & Butler, 1855.

- For further information on the naturalization of the Bonin Islanders, see David Chapman, The Bonin Islanders, 1830 to the Present (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2016), 73-102.

- These three terms are problematic in their own way if applied to the original Bonin Islanders and their descendants, but that is a topic beyond the scope of this paper.

- Among them was a prominent German-born geneticist. Richard Goldschmidt, “Die Nachkommen der alten Siedler auf den Bonininseln,” Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Natur-Und Volkerkunde Ostasiens, vol. XXII, section B (1928): B2-B3.

- For further information on the American occupation of the Bonins, see Robāto D. Erudorijji, Iwo jima to Ogasawara o meguru Nichibei kankei (Kagoshima: Nanpō Shinsha, 2008).

- Samuel Jameson, “Navy’s ‘Mystery Base’ in Bonins Irks Japanese,” Chicago Tribune, sec. 1A, November 1, 1964.

- Ibid.

- Dorothy Richard Pesce and Gordon Findley, A History of the Bonin-Volcano Islands (US Navy declassified document, 1958), 337.

- Chapman, 175-176; Commodore M. C. Perry, Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan (Washington: Beverley Tucker, 1856), 283.

- Interview with an island resident, June 2013.

- Chapman, 197-198.

- The 1968 reversion of the Bonin Islands is a complicated topic, in part, because it is deeply intertwined with the 1972 reversion of Okinawa. After passing control over to the Japanese government, the United States did not seek to maintain naval bases in the Bonin Islands.

- Yamazaki Masayuki, “‘Enshutsu’ sareru Ogasawara: Shintōmin to yobareru ijūsha o megutte” (PhD dissertation, Waseda University, 2017), 64-65, 68.

- Ogasawara-mura, “Ogasawara-mura jinkō bijon, sōgō senryaku” (Tokyo: Ogasawara-mura, 2016), 5.

- Abe Shin, Ogasawara shotō ni okeru Nihongo no hōgen sesshoku (Kagoshima: Nanpō Shinsha, 2006), 65.

- Kokudo kōtsūshō, “Heisei 26 nendo chihō zeisei kaisei (zeifutan keigen shochi nado) yōbō jikō,” no. 17 (2014): 3.

- Abe, 65.

- Ogasawara-mura, 11.

- Martin Fackler, “A Western Outpost Shrinks on a Remote Island Now in Japanese Hands,” New York Times, June 10, 2012.

- Interview with an island resident, June 2013.

- Tabata, 7-11. This issue aside, Tabata Michio’s book is evenhanded and well researched.