Introduction

In recent years we have seen a worldwide increase in debates surrounding memorials that celebrate historical personalities. In the United States, statues of generals who commanded the troops of the Confederacy in the Civil War (1861-65) have been demolished or strongly criticized as inappropriate. In Oxford, students have demanded the removal of a statue of Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) because of the role he played in British imperialism and his advocacy of racist ideology, which is today widely considered offensive. In 2015, the University of Cape Town removed a statue of Rhodes, which had been erected in 1934 near the entrance to the campus. In Namibia, the statue of a German colonial soldier was demolished in 2009 and later re-erected at a less prominent position, only narrowly escaping complete destruction.1 In some cases, the controversies around these monuments have led to violent clashes between those who consider them remnants of a former age, out of sympathy with the twenty-first century zeitgeist, and those who either favor their preservation as part of the country’s “culture and heritage” or who continue to espouse the ideologies the statues represent.

In Japan, heated controversies over public statues and the historical roles played by the personalities they represented were common in the prewar and in the immediate postwar era. Today, however, such debates are rather muted, suggesting a low degree of historical awareness in contemporary society. This article examines earlier controversies and explains the reasons for postwar public silence over public statues.

Statues of controversial figures in prewar Japan

The erection of public statues in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Japan was often accompanied by heated discussion, reflecting vigorous historiographical debates over the historical significance and achievements of the individuals commemorated. In particular, many of these debates mirrored competing assessments of the history of the Meiji Restoration of 1868, i.e. the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and the establishment of a central government legitimized by the rhetoric of “direct imperial rule.” The government of the Meiji era (1868-1912) was comprised of leaders who had fought the shogunate and had prevailed in the civil war of the 1850s and 1860s. Their views dominated the historical narrative of Meiji Japan, and this narrative in turn shaped the development of public statuary in modern Japan.2

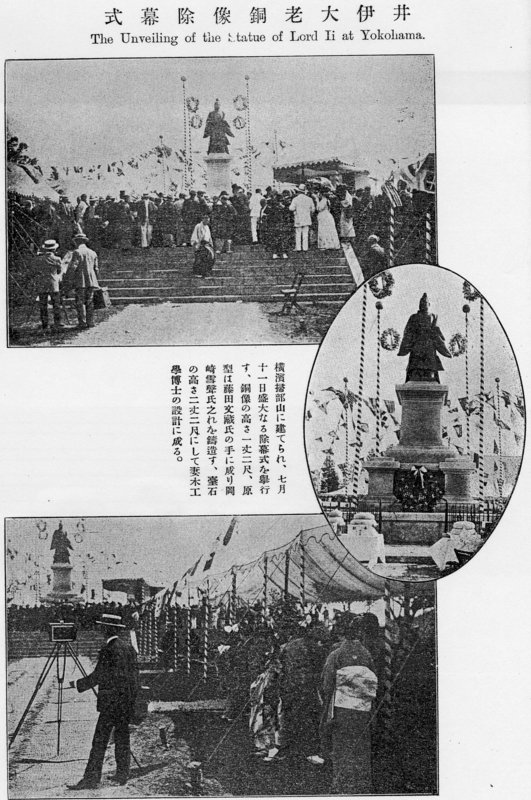

Among the most controversial statues erected during the Meiji era was a monument to the shogunate regent (tairō), Ii Naosuke (1815-1860). Under Ii’s rule, the shogunate had cracked down on the anti-Tokugawa movement. During the Ansei purge of 1858, for which he was directly responsible, several leaders of the rebel movement were executed. After the followers of these slain leaders had prevailed in the civil war and established a new government, Ii was branded a traitor and an “enemy of the court” (chōteki). When Ii’s former vassals proposed erecting a statue to him in 1881, these plans were understandably not well received by the representatives of the government – the supporters of the former anti-Tokugawa movement, which Ii had so harshly repressed in the late 1850s. It would only be in 1909 that a statue of Ii became a reality, and it had to be erected in Yokohama rather than in Tokyo, as originally planned. The background to Yokohama as the site for the statue was Ii’s 1854 decision to open Japan to relations with Western countries, which had led to the opening of Yokohama as a treaty port. The statue was erected to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the birth of that city. The inauguration festivities indicated that by 1909 the historical assessment of Ii had changed, even among the cliques dominating the government. Elder statesman and founder of Waseda University Ōkuma Shigenobu (1838-1922) gave a speech at the inauguration ceremony and emphasized that far from being an “enemy of the court,” Ii’s decision to open the country to foreign contact was that of a true patriot, an action that had saved Japan from the fate of colonization.

|

Coverage of the unveiling ceremony of the statue of shogunate regent Ii Naosuke in Yokohama, 1909 in the journal Taiyō. |

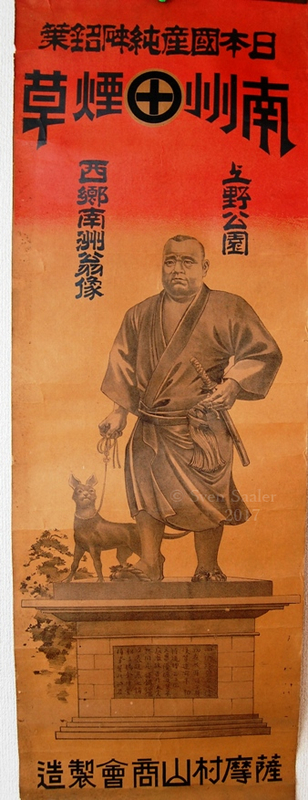

The attention the Ii statue received when it was erected in 1909 did not compare with the extensive publicity given to similar ceremonies in the 1880s, given that over 100 public statues had been built by the late Meiji era. The groups dominating the new government had all put up monuments to their heroes in public spaces. For example, a statue of the founder of the Imperial Japanese Army, Ōmura Masujirō (1824-1869), representing a clique of politicians from the former feudal domain of Chōshū (today’s Yamaguchi Prefecture), was erected at the Yasukuni Shrine in 1893. A statue of Saigō Takamori (1828-1877), the leading figure of the clique of politicians from the former Satsuma feudal domain (today’s Kagoshima Prefecture), was put up in Ueno Park in 1898. This statue was as contested as that of Ii. While originally a member of the anti-Tokugawa movement and the new Meiji government, Saigō had eventually rebelled against the central government – and thus against the emperor – in what is known as the Satsuma Rebellion or the Southwest War (1877). Branded a traitor and an enemy of the court (chōteki), as Ii had been, he and other chōteki were pardoned in 1889, when the Constitution of the Empire of Japan was promulgated and the creation of the Meiji state had been completed. Following his pardon, plans to build a statue to Saigō gained traction. However, it would take almost ten years before the statue was completed, and the plans had to be adjusted following a heated public debate. Originally planned to stand in front of the imperial palace, Saigō eventually had to “take refuge” in Ueno Park, a site associated with the shogunate and the enemies of the imperial court. Although his monument was planned to be Japan’s first equestrian statue, showing Saigō in military uniform, the final design shows him dressed in a simple kimono, as a private citizen walking his dog (see illustration 3).

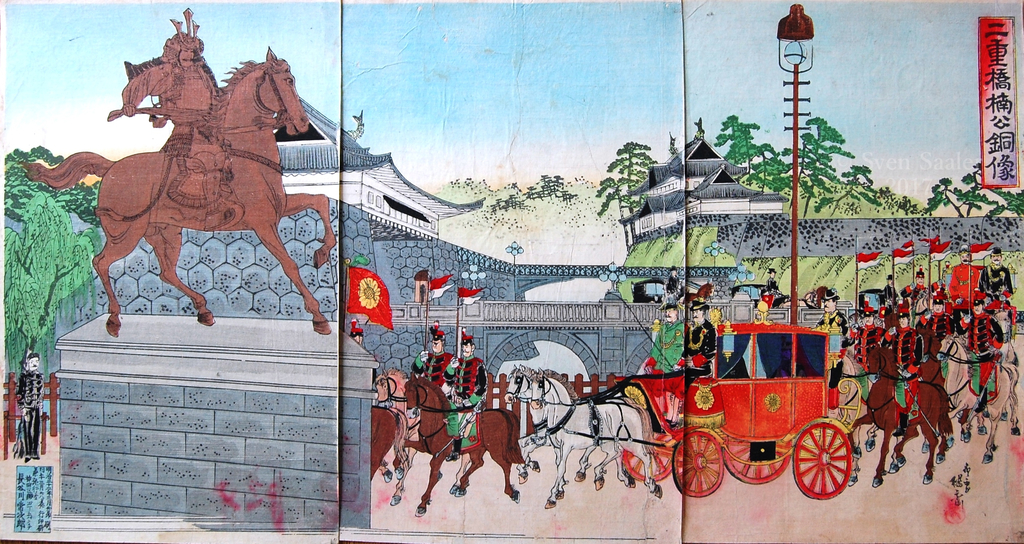

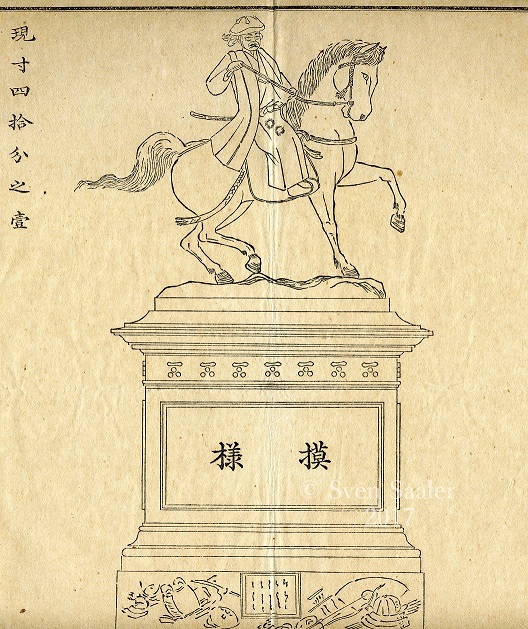

The site originally chosen for Saigō’s statue was eventually occupied by the figure of a “true” loyalist to the imperial court – medieval warrior Kusunoki Masashige (1294-1336). Kusunoki’s statue, however, was narrowly beaten in the race to become Japan’s first equestrian statue by that of another feudal lord, the daimyo of Chōshū feudal domain, Mōri Takachika (aka Yoshichika, posthumous name Tadamasa, 1819-1871; see below). The Mōri statue was unveiled on 15 April 1900, while the Kusunoki statue was placed on its pedestal in May of the same year and unveiled in July.3

|

Statue of Kusunoki Masashige in front of the imperial palace, Tokyo (woodblock print, 1899, © Sven Saaler). |

|

Tobacco advertisement showing the statue of Saigō Takamori in Ueno Park, Tokyo (late Meiji/Taishō period, © Sven Saaler). |

Although many prewar statues were destroyed during World War II, most of these early Meiji period statues survived to the present day. While they have become important landmarks symbolizing the sites where they stand, they also remain significant manifestations of the nation in public spaces, inculcating visitors with an official imprimatur of the idea of the nation. More importantly, their presence is not limited to the actual sites where they stand: they occupy a significant place in the mass media in modern Japan, being reproduced on woodblock prints (see illustration 2), lithographs, postcards (illustration 5), in tourist guidebooks and periodicals, on the internet and in advertisements (illustration 3), as well as on Japan’s currency (illustration 4).

|

Five-sen bill of 1944 showing the statue of Kusunoki Masashige (© Sven Saaler). |

A nationwide phenomenon

The commissioning of public statuary was not restricted to the capital. In fact, the first statues of modern Japan were built in the countryside, where the agents of the newly founded nation-state came to see that statues in public spaces could help spread the new – and at that time little-known – idea of Japan as a nation.

The first modern bronze statue of a historical personality commissioned in Japan was erected in 1880 in the city of Kanazawa. The statue shows Yamato Takeru, a figure from Japanese mythology who, nonetheless, was considered an historical personage in prewar Japan. According to the myth, Yamato was the son of Emperor Keitai and was sent by his father to subdue those resisting imperial rule in Kyushu and Eastern Japan. As a military commander, he was seen as a representative of the military prowess of the imperial dynasty. After the Meiji Restoration –following the restoration of both “direct rule” and the supreme military command of the emperor – Yamato Takeru was chosen to embody the tradition of the imperial dynasty’s commanding role in military affairs.

The plans for Yamato’s statue were initiated by the prefectural governor and the commander of the Imperial Japanese Army forces stationed in Kanazawa – the representatives of the central state in this important regional city.4 The statue was linked to plans to build a memorial to commemorate 400 soldiers from Kanazawa who had been sent to suppress the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877 and had lost their lives during their mission. It was put up in Kenrokuen – the former garden of the daimyo’s castle, which became one of Japan’s first public parks in 1874.

|

Statue of Yamato Takeru in Kenrokuen, Kanazawa (prewar postcard, © Sven Saaler). |

Further statues were erected in prefectural cities soon afterwards, including a (stone) statue of Emperor Keitai in Fukui (1883), bronze statues of Emperor Jimmu in Tokushima (1896) and Toyohashi (1899), and one of Yamagata Aritomo (1838-1922) from Chōshū in the former capital city of this feudal domain, Hagi (1898). The monument to Yamagata was one of the first examples of a large statue in a public space depicting a statesman who was not only still alive, but also a major public figure – five months after the statue was erected, Yamagata was appointed prime minister for the second time. Yamagata’s statue was erected even before monuments dedicated to the feudal lords of Chōshū were completed, demonstrating that feudal hierarchies had become less dominant in Japanese society.

Plans for statues depicting the daimyo of the Mōri family, which had ruled the Chōshū domain from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, were set in motion in the early 1890s, but it was not until 1900 that the statues were unveiled in Kameyama Park in Yamaguchi city. While the Yamagata statue in Hagi was initiated and financed by fellow statesman Katsura Tarō (1848-1913), the statues of the Mōri lords were the brainchild of one of the most influential politicians of the Meiji period from Chōshū, Itō Hirobumi (1841-1909), working in concert with Hayashi Tomoyuki (1823-1907), a member of the Upper House of the Imperial Diet and later of the Privy Council. They were financed by donations from the “people of Yamaguchi” (Yamaguchi kenmin), as the monuments’ inscriptions put it. Although the initial plan had focused on the equestrian statue of Mōri Takachika discussed above (see illustration 6), the project evolved to become a set of five daimyo statues. A sixth was added in 1906, once again initiated by Katsura Tarō. All these statues were erected to underline and demonstrate the role of the Chōshū feudal domain and its lords in the process of unifying Japan. Of course, their commissioning was also an act of feudal loyalty on the part of Itō, Katsura, Hayashi and others as vassals of the former feudal lords.

|

Sketch of an equestrian statue of feudal lord Mōri Takachika of the Chōshū domain, which was a part of a prospectus and a call for donations to cover the monument’s expenses (1893, © Sven Saaler). |

The Emperor’s invisibility in public space

While altogether around 900 statues of various public figures were built in Japan between 1880 and 1940, a conspicuous feature of public statuary in modern Japan is the invisibility of the reigning Emperor. We find statues of mythical emperors, such as Jimmu and Keitai, but not a single statue of Meiji Tennō was put up in an outdoor public space until 1968, and no statues of Taishō Tennō and Shōwa Tennō have ever been erected. Several attempts were made in prewar Japan to commission a statue of the Meiji Emperor, following the fashion for statues of monarchs in public space in Europe.5 When the emperor died in 1912, the daily newspaper Yomiuri Shinbun published a plan to mass-produce a 50cm high statuette of the emperor, which would be sold to subscribers for 70 Yen apiece (equivalent to 77,000 Yen at today’s values). Around the same time, former Imperial Household Minister Tanaka Mitsuaki (1843-1939), a zealous worshipper of Meiji Tennō, commissioned a life-sized statue of Meiji, which he planned to present to the Empress Dowager Shōken (1849-1914). It shows the late Emperor in military uniform, very similar to his popular official portrait, but standing, and with a saber in his hand (see illustration 7). It took two years to complete. The statue was designed by Watanabe Osao (1874-1952) and cast in bronze in March 1914 by Okazaki Sessei (1854-1952). The metal used was donated by corporations with copper-producing facilities,6 including Furukawa (which ran the Ashio copper mines), Kuhara (Hitachi) and Sumitomo (Besshi). All these firms were involved in multiple statue projects; Sumitomo had, for example, built the Kusunoki statue discussed above. After the Empress Shōken died on 9 April 1914, the completed statue was given to Emperor Taishō in October that year. It was later moved to the Momijiyama Archives of the Imperial Household Ministry, where it remained until after World War II. In 1980, the Shōwa Emperor presented the statue to the Meiji Shrine, where it is stored today.

|

Newspaper insert showing a life-sized statue of Meiji Tennō (1927). |

At least one copy of this statue at its original size (175 cm) was cast in later years and was owned privately by Tanaka Mitsuaki. In 1929, Tanaka founded a memorial hall dedicated to Meiji Tennō in Ibaraki, the Jōyō Meiji Kinenkan (Jōyō Meiji Memorial), and donated his Meiji statue to the museum, where the “Sacred Statue” (seizō) remains on display to the present day. (Today the museum is known as the Ōarai Museum of Bakumatsu-Meiji History or Bakumatsu to Meiji no Hakubutsukan.)7

One medium-sized statue of the same design, 94 cm high, even found its way abroad. This image of the Meiji Emperor became a sacred object of worship in the Dairen Shrine in the city of Dalian (Dairen) in the Japanese-leased territory of Kwantung (Kantō) in southern Manchuria. When Japan surrendered in 1945 and Russian troops occupied the city, the head priest of the shrine feared that Soviet soldiers would confiscate or destroy the statue. However, to his surprise, the Soviets, though clearly not fond of symbols of Japan’s monarchy and its military, allowed him to take the massive statue with him when he was repatriated to Japan in 1947.

A single equestrian statue of Meiji Tennō was also built – again on the initiative of Tanaka Mitsuaki, and again for a new memorial hall dedicated to the Emperor. It was unveiled on 9 November 1930 at the Tama Seiseki Kinenkan (Tama Seiseki Memorial Hall), where it still stands today.8 However, apart from mythical emperors such as Jimmu and Keitai, the imperial family remained virtually out of sight in public spaces. The statues of the Meiji Emperor were hidden within memorials rather than being put up in outdoor public spaces, and the location of the memorials was also a secure distance from the urban centers of Tokyo. This would not drastically change in the postwar era, notwithstanding the fact that the Emperor’s position changed: since his “Declaration of Humanity” in January 1946, he was no longer considered a sacred being; however, a somewhat sacred aura surrounds the monarch until today. Thus, the first outdoor statues of the Meiji Emperor only appeared in 1968, as a result of the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration in 1968, but overall, such statues remain rare until the present day.

Wartime destruction and postwar resurgence of public statuary

From 1937, Japan was engaged in total war with China and in 1938, the Imperial Diet passed the National Mobilization Law, which regulated the utilization of metals. Bronze and copper, the chief materials used in public statuary, were no longer allocated to Japan’s sculptors and metal casters. Stocks were handed over to the war industry for the production of armaments and ammunition and the building of statues largely ceased by 1940.9

In 1943, the government went a step further and began to promote the collection of metals of all kinds. In 1944, the Minister of Munitions, Tōjō Hideki (1884-1948), who also happened to be prime minister, convened a committee to categorize Japan’s public statues, deciding which to preserve and which to melt down. Statues to be preserved were mostly figures from the imperial house and monuments dedicated to major national heroes – to destroy them would only harm national morale. Only around 100 of Japan’s public statues would survive the war; the rest were removed from their pedestals and melted down.

After Japan’s defeat in the war, the occupation authorities did not directly order the destruction of any further statues. Committees were established on the local level to discuss which monuments were inappropriate for the “New Japan,” a peaceful and cultured state whose military had been abolished and, by 1947, constitutionally prohibited. However, none of the remaining statues were destroyed. Any considered offensive were relocated or temporarily removed, but only to be reinstated years later, though often in less prominent positions. A statue of General Yamagata Aritomo, for example, once sited in front of the Imperial Diet, was temporarily stored outside of a museum in Ueno before being moved to Inokashira Park in suburban Kichijōji in 1962. In 1992, it was again relocated, this time to the city of Hagi, Yamagata’s hometown, where it stands today.

Many, if not most, of the statues erected in prewar Japan were recreated in the postwar era. One of the first examples was a statue of Ii Naosuke. Given his role as a “villain” of the Meiji Restoration, it is unsurprising that he was not spared during the wartime mobilization effort. His statue in Yokohama and another in Hikone, the capital of his former feudal domain, were demolished and melted down in 1944. However, given that he was instrumental in signing the first treaty between Japan and a foreign country – the United States, the leading power in the postwar occupation of Japan – the city of Hikone decided to erect a new statue of Ii. Completed in 1949, it was one of the first prewar statues to be reinstated. According to the inscription, it was erected as a memorial to a “pioneer of Japanese–American friendship,” emphasizing the legitimacy of Ii’s decision to open the country in the 1850s and signing a treaty with the U.S. Ii’s statue in Yokohama was rebuilt five years later, in 1954, and many statues of feudal lords that had been sacrificed to the war effort followed suit. The latest addition is a figure of the last daimyo of Saga domain, Nabeshima Naomasa (1814-1871), unveiled in March 2017.

|

Unveiling ceremony for the statue of Nabeshima Naomasa in Saga, 2017 (© Sven Saaler). |

Recent Developments

Today, more than 2,000 statues of historical personages are displayed in public places throughout Japan. While some depict figures who played controversial roles, most of these statues were installed with little debate. If one group was dissatisfied with the building of a monument for an individual it did not like, then the group would organize the building of a statue for its own hero, but not campaign for demolishing the other. Thus, in Japan, statues have been commissioned to celebrate the “heroes” of the Meiji Restoration on the one side and, on the other, representatives of the shogunate forces that slaughtered these very heroes; they commemorate both those deemed to be responsible statesmen as well as terrorists involved in the assassination of these same statesmen, such as Inoue Nisshō (1886-1967);10 they honour extreme xenophobes in addition to a surprisingly large number of foreigners.11 Because postwar Japan took pride in its image as a “peace state” (heiwa kokka), apart from the statues of the premodern feudal lords, few statues of military figures have been erected since 1945. In order to underline the image of Japan as a “culture state” (bunka kokka), a larger number of statues of poets, composers and doctors have been built in recent decades. The famous poet Bashō (1644-94) is the individual to whom the largest number of statues have been dedicated. The statues of composer Taki Rentarō (1879-1903) and of bacteriologist Noguchi Hideyo (1876-1928), both placed in Tokyo’s Ueno Park in the early postwar period, are examples of statues of figures representing a modern, peaceful and cultured Japan.

As a result of the increasing proliferation of statues of historical figures, the statue-building boom in postwar Japan has led to a “ceasefire” in Japan’s wars over the memory of historical personalities. Historical figures representing a broad variety of historical figures have been staged in the public sphere. Since the majority of public statues in contemporary Japan is dedicated to historical figures linked to the Meiji Restoration, however, the coming 150th anniversary of this event in 2018 could lead to a revival of these debates, as the recent publication of books with such provocative titles as “The Meiji Restoration was a Mistake—Yoshida Shōin and the Chōshū Terrorists Destroyed Japan”12 indicates.

Notes

See Joachim Zeller, “Das Reiterdenkmal in Windhoek (Namibia) – Die Geschichte eines deutschen Kolonialdenkmals.”

For a summary of the historiographical debates around the Meiji Restoration, see Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. Szpilman, “Introduction,” in Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. Szpilman (eds), Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History, Routledge, 2018.

For more on the statues of Mōri and Kusunoki, see Sven Saaler, “Men in Metal: Representations of the Nation in Public Space in Meiji Japan, 1868-1912,” Comparativ. Zeitschrift für Globalgeschichte und vergleichende Gesellschaftsforschung 19, 2009, pp. 27-43.

Regarding the development of modern Kanazawa, see Louise Young, Beyond the Metropolis. University of California Press, 2013; Louise Young, “Urban life and the city idea in the twentieth century,” in Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. Szpilman (eds), Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History, Routledge, 2018.

Research on the modern statuary of Europe usually focuses on one country. For France, see Hargrove, June (1990), The Statues of Paris: An Open-Air Pantheon. New York and Paris: Vendome Press; for Germany, see Alings, Richard (1996): Monument und Nation: Das Bild von Nationalstaat im Medium Denkmal. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter. Highly informative regarding statues in the German kingdom of Wurttemberg is Alan Confino, The Nation as a Local Metaphor: Wurttemberg, Imperial Germany, and National Memory, 1871-1918: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. For a general overview of modern statuary in Europe, see Michalski, Sergiusz (1998), Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage 1870-1997. Clerkenwell: Reaktion Books. The statues of the United States and, in particular, those of the Confederacy, are addressed in Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1913, Oxford University Press, 1988.

The last major public statue built was the monument dedicated to Nara-era court noble Wake no Kiyomaro near the Imperial Palace, which was inaugurated in 1940. Between 1940 and 1945, less than ten public statues were built.

Inoue was one of the founders of the right-wing organization Ketsumeidan (Blood Pledge Corps). Its motto was “One Man, One Assassination,” and the group is usually held responsible for the assassination of former finance minister Inoue Junnosuke on 9 February 1932, of Director-General of the Mitsui conglomerate, Baron Dan Takuma, on 5 March 1932 (Blood Pledge Corps Incident), and of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyhoshi on 15 May 1932 (15 May Incident). See here.

Famous examples are the statues of foreign professors on the campus of The University of Tokyo or the statue of Commodore Matthew C Perry in Shimoda, where he landed in 1854 to sign a treaty with which Japan was to open relations with the United States.

Harada Iori, Meiji ishin to iu ayamachi. Nihon o horoboshita Yoshida Shōin to Chōshū terorisuto. Mainichi Wanzu, 2015.