On the crisp autumn afternoon of November 26, 2007, a black car picked up Graham Spanier, then president of Pennsylvania State University, at Dulles International Airport and whisked him to CIA headquarters in Langley, Va. Using his identification card — embedded with a hologram and computer chip — he checked in at security and was greeted by the chief of staff of the National Resources Division, the CIA’s clandestine domestic service. They proceeded to a conference room, where about two dozen chiefs of station and other senior CIA intelligence officers awaited them.

Spanier was expecting to brief them on the work of the National Security Higher Education Advisory Board, an organization he chaired and had helped create, which fostered dialogue between intelligence agencies and universities. First, though, the CIA surprised him. In a brief ceremony, it presented him with the Warren Medal, said to be the agency’s highest honor for nonemployees.

|

Graham Spanier |

The honor recognized Spanier’s dedication to alerting college administrators to the threat of human and cyber-espionage, and to opening doors for the agency at campuses nationwide. A former family therapist and television talk-show host with an unruffled, empathetic manner and features — round face, white hair, blue eyes—reminiscent of Phil Donahue, Spanier soothed many an academic’s anxieties about dealing with the CIA and the FBI.

Since the intelligence agencies were going to meddle anyway, Spanier reasoned, they should do so with the knowledge and consent of college presidents. “My feeling was, If there’s a spy on my campus, a potential terrorist, or a visiting faculty member you believe is up to no good, I know you’ll be pursuing it,” he told me in April 2016. “Here’s the deal. Rather than break into his office, come to me — I have top-secret clearance — show me your FISA [Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act] order, and I’ll have someone unlock the door.”

Spanier’s CIA medal, and a similar FBI award a year later, symbolized a reconciliation between the intelligence services and the academy. The relationship has come full circle: from chumminess in the 1940s and 1950s, to animosity during the Vietnam War and civil-rights era, and back to cooperation after the September 11, 2001, attacks.

US Intelligence and the Universities

Their unequal partnership, though, tilts toward the government. U.S. intelligence seized on the renewed goodwill, and the red carpet rolled out by Spanier and other university administrators, to expand not only its public presence on campus but also covert operations and sponsoring of secret research. Federal encroachment on academic prerogatives has met only token resistance.

The two cultures are antithetical: Academe is open and international, while intelligence services are clandestine and nationalistic. Still, after Islamic-fundamentalist terrorists toppled the World Trade Center, colleges became part of the national security apparatus. The new recruiting booths at meetings of academic associations were one telling indicator. The CIA began exhibiting at the annual convention of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages in 2004, as did the FBI and NSA around the same time. Since 2011 the FBI, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and the National Security Agency have participated on a panel at the Modern Language Association convention titled “Using Your Language Proficiency and Cultural Expertise in a Federal Government Career.”

|

Today universities routinely offer degrees in homeland security and courses in espionage and cyber-hacking. They vie for federal designation as Intelligence Community Centers for Academic Excellence and National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cyber Operations. They obtain research grants from obscure federal agencies such as Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity. Established in 2006, Iarpa sponsors “high-risk/high payoff research that has the potential to provide our nation with an overwhelming intelligence advantage,” according to its website. To date, it has funded teams with researchers representing more than 175 academic institutions, mostly in the United States.

While almost all Iarpa projects are unclassified, colleges increasingly carry out secret but lucrative government research at well-guarded facilities. Two years after the 9/11 attacks, the University of Maryland established a center that conducts classified research on language for the Pentagon and intelligence agencies. Edward Snowden worked there in 2005 as a security guard, eight years before he joined the government contractor Booz Allen Hamilton Inc. and leaked classified files on NSA surveillance.

The center is located off-campus. Like many universities, Maryland forbids secret research on campus, but its transparency stops at the far side of its neatly trimmed lawns.

Other universities have no such compunctions. “Classified research on campuses, once highly controversial, is making a comeback,” VICE News reported in 2015. The National Security Agency in 2013 awarded $60 million to North Carolina State University in Raleigh, the largest research grant in the university’s history, to create an on-campus laboratory for data analysis. Virginia Tech established a private nonprofit corporation in December 2009 to “perform classified and highly classified work” in intelligence, cybersecurity, and national security. Two years later, the university planted its flag on prime intelligence-community turf. It opened a research center in Ballston, a neighborhood in Arlington, Va., across the Potomac River from Washington, brimming with CIA and Pentagon contractors. The center features facilities for, according to the university, “conducting sensitive research on behalf of the national security community.”

The Origins of the Relationship Between Intelligence and the Universities

Academe was present at the CIA’s creation. Its precursor, the Office of Strategic Services, founded in 1942, was “half cops-and-robbers and half faculty meeting,” according to McGeorge Bundy, an intelligence officer during World War II and later national security adviser to the presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. The OSS was largely an Ivy League bastion. It attracted 13 Yale professors in its first year, along with 42 students from the university’s Class of 1943. A Yale assistant professor, under cover of acquiring manuscripts for the university library, became OSS chief in Istanbul.

When the CIA was established, in 1947, the Ivy influence carried over. Skip Walz, the Yale crew coach, doubled as a CIA recruiter, drawing a salary of $10,000 a year from each employer. Every three weeks he supplied names of Yale athletes with the right academic and social credentials to a CIA agent whom he met at the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool, in Washington. Although the agency gradually expanded hiring from other universities, 26 percent of college graduates whom it employed during the Nixon administration had Ivy League degrees. The agency helped establish think tanks and research centers at several top universities, such as MIT’s Center for International Studies in 1952.

Almost from its inception, the CIA cultivated foreign students, recognizing their value as informants and future government officials in their homelands. It learned about them not only through their professors but also through the CIA-funded National Student Association, the largest student group in the United States. With only 26,433 international students in the United States in 1950, less than 3 percent of today’s total, the CIA relied on the association to identify potential informants at home and abroad.

The agency, which supported the student association as a non-Communist alternative to Soviet-backed student organizations, meddled in the group’s election of officers and sent its activists, including the future feminist Gloria Steinem, to disrupt international youth festivals. “In the CIA, I finally found a group of people who understood how important it was to represent the diversity of our government’s ideas at Communist festivals,” Steinem told Newsweek in 1967. “If I had the choice, I would do it again.” With an assist from the CIA, the number of foreign students in the United States almost doubled from 1950 to 1960.

The Relationship Unravels

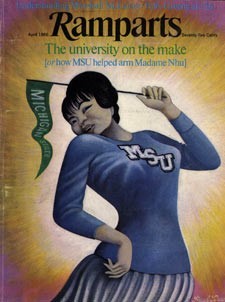

Then it all unraveled. Ramparts, a monthly magazine that opposed the Vietnam War, reported in 1966 that a Michigan State University program to train the South Vietnamese police had five CIA agents on its payroll. A year later, Ramparts revealed the CIA’s involvement in the National Student Association, stirring a national outcry. The Johnson administration responded by banning covert federal funding of “any of the nation’s educational or private voluntary organizations” — though not of their individual members or employees.

|

Privately, Johnson saw the hand of world Communism in both the Ramparts exposé and the antiwar protests, and ordered the CIA and FBI to prove it. FBI penetration and surveillance — including illegal wiretaps and warrantless searches — expanded under President Richard Nixon but failed to turn up evidence of foreign funding.

The government’s crackdown on its campus critics, along with CIA blunders such as the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, in 1961, fractured the camaraderie between intelligence agencies and academe. In 1968 alone, there were 77 instances of picketing, sit-ins, and other student protests against CIA recruiters.

The disaffection was mutual. Just as Ivy League graduates began having doubts about joining the CIA, so older alumni who devoted their careers to intelligence agencies bridled at the antiestablishment campus mood. “It is not true that universities rejected the intelligence community: that community rejected universities at least as early,” the Yale historian Robin Winks wrote.

Hostility between the intelligence services and universities peaked with the 1976 report of the Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, usually known as the Church Committee, after its chairman, Senator Frank Church of Idaho. In the most comprehensive investigation ever of U.S. intelligence agencies, the committee documented an appalling litany of abuses, some undertaken by presidential order and others rogue. The CIA, it found, had tested LSD and other drugs on prisoners and students; opened 215,820 letters passing through a New York City postal facility over two decades; and tried to assassinate the Cuban dictator Fidel Castro and other foreign leaders. The FBI, for its part, had harassed civil-rights and anti-Vietnam War protesters by wiretapping them and smearing them in anonymous letters to parents, neighbors, and employers.

The committee also exposed clandestine connections between the CIA and higher education. The agency was using “several hundred academics” at more than a hundred U.S. colleges for, among other purposes, “providing leads and, on occasion, making introductions for intelligence purposes,” typically without anyone else on campus being “aware of the CIA link.”

Bowing to the CIA’s insistence on protecting its agents, the committee didn’t name the professors or the colleges where they taught. Typically, the academics helped with recruiting foreign students. A professor would invite an international student — often from a Soviet-bloc country, or perhaps Iran — to his office to get acquainted. Flattered by the attention, the student would have no clue he was being assessed as a potential CIA informant. The professor would then arrange for the student to meet a wealthy “friend” in publishing or investing. The friend would buy the student dinner and pay him generously for an essay about his country or his research specialty.

Unaware he was being compromised, the grateful student would compose one well-compensated paper after another. By the time the professor’s friend admitted that he was a CIA agent, and asked him to spy, the student had little choice but to agree. He couldn’t report the overture to his own government, because his acceptance of CIA money would jeopardize his reputation in his homeland, if not his freedom.

The Church Committee and the Attempt to Control CIA Activity on Campus

Morton Halperin knew about this deception and found it “completely inappropriate.” He intended to end it once and for all. The Church Committee’s report showed him the way.

From a bookshelf in his office at the Open Society Foundations in Washington, where he is a senior adviser, Halperin extracts the first volume of the committee report. He opens the thumb-worn paperback to a passage he had underlined 40 years before: “The Committee believes that it is the responsibility of private institutions and particularly the American academic community to set the professional and ethical standards of its members.” That sentence sent him on a quest to persuade colleges to stand up to U.S. intelligence agencies and curb covert activity on their campuses. His mission would provoke an unprecedented confrontation between the CIA and the country’s most famous university. Its outcome would shape the relationship between U.S. intelligence and academe and still has repercussions today.

Halperin had Ivy League credentials as impeccable as any CIA recruit’s: a bachelor’s degree from Columbia and a Yale doctorate, followed by six years on the Harvard faculty. A former White House wunderkind who’d taken a top Pentagon post under President Johnson before turning 30 and then joined the National Security Council staff under President Nixon, Halperin had himself become a target of the government’s covert operations, largely because of his misgivings about the Vietnam War. With the approval of his mentor, Henry Kissinger, then national-security adviser, the Nixon administration tapped Halperin’s home phone in 1969, suspecting him of leaking information about the secret bombing of Cambodia to reporters. It also placed him near the top of Nixon’s notorious “enemies list.”

As director of the Center for National Security Studies, a project of the American Civil Liberties Union, Halperin had lobbied Congress to create the Church Committee. He attended its hearings and testified before it, urging a ban on clandestine operations because they bypass congressional and public oversight and are incompatible with democratic values.

Armed with the committee’s recommendation, he approached Harvard and asked it to set rules for secret CIA activity on campus. He expected that any restrictions placed by the nation’s most prominent university would spread throughout academe.

Morton Halperin, Harvard and the CIA

Harvard General Counsel Daniel Steiner, whom Halperin contacted first, was sympathetic, and urged President Derek Bok to take up the issue. As it happened, Bok was already familiar with the Church Committee. Its chief counsel, Frederick A.O. (“Fritz”) Schwarz Jr., was a family friend and former law student of Bok, who admired his political activism, especially on civil rights. As a third-year Harvard law student in 1960, Schwarz had organized a protest in Cambridge to support a sit-in by blacks at the lunch counter of a Woolworth’s department store in Greensboro, North Carolina, that refused to serve them.

“I can still remember walking into Harvard Square on a rainy day,” Bok said in a 2015 interview. “There in front of Woolworth’s were Schwarz and another student picketing over Woolworth’s refusal to serve Negroes in the South.”

Bok had also met with Church Committee member Charles Mathias, a Republican senator from Maryland, and staff director William Miller, to discuss whether the committee should call for a federal law banning covert intelligence gathering on campus. Bok knew both of them slightly. Miller had been a graduate student in Renaissance literature at Harvard, while Bok had lobbied Mathias in 1970 against G. Harrold Carswell, whom Nixon had nominated for the U.S. Supreme Court despite an indifferent reputation as a federal district court judge. Mathias had impressed Bok by carefully reviewing Carswell’s record and then bucking a president from his own party and voting against the nomination, which was defeated 51-45.

Universities typically oppose any extension of federal power over academic decisions. Reflecting this view, Bok told Mathias and Miller at their meeting that colleges, not the government, should take the lead in curtailing covert operations. They agreed.

“The integrity of the institutions required it,” Miller said in a 2015 interview. “It could not be imposed from outside.”

Bok appointed four sages to set standards. They included Steiner and Harvard law professor Archibald Cox, who had become famous during the 1973 “Saturday Night Massacre,” when President Nixon fired him as special prosecutor for the Watergate scandal. Steiner met with top CIA officials, including Cord Meyer Jr., who had overseen the agency’s hidden role in the National Student Association. Based on their discussions, Steiner wrote to Meyer, “I would conclude that the CIA feels it is appropriate to use, on a compensated or uncompensated basis, faculty members and administrators for operational purposes, including the gathering of intelligence as requested by the CIA, and as covert recruiters on campus.”

The Harvard wise men disagreed. Their 1977 guidelines prohibited students and faculty members from undertaking “intelligence operations” for the CIA, although they could be debriefed about foreign travels after returning home. “The use of the academic profession and scholarly enterprises to provide a ‘cover’ for intelligence activities is likely to corrupt the academic process and lead to a loss of public respect for academic enterprises,” they wrote.

Also forbidden was helping the CIA “in obtaining the unwitting services of another member of the Harvard community” — in other words, recruiting foreign students under false pretenses. To Bok and his advisers, this perverted the trust between professor and student on which higher education is built. Posing as a mentor, a professor might seek a foreign student’s views on international affairs, or ask about his financial situation, not to guide him but to help the CIA evaluate and enlist him. And, once it snared the student, the agency might ask him to break the laws of his home country — a request that Harvard couldn’t be a party to.

“Many of these students are highly vulnerable,” Bok told the Senate in 1978. “They are frequently young and inexperienced, often short of funds and away from their homelands for the first time. Is it appropriate for faculty members, who supposedly are acting in the best interests of the students, to be part of a process of recruiting such students to engage in activities that may be hazardous and probably illegal under the laws of their home countries? I think not.”

The Harvard committee acknowledged that its new rules made the CIA’s job harder. “This loss is one that a free society should be willing to suffer,” it said.

Admiral Stansfield Turner saw no reason to suffer. CIA director from 1977 to 1981, he believed that the agency should take advantage of the presence of foreign students on U.S. soil. Since recruiting foreigners in totalitarian countries is difficult, “it would be foolish not to attempt to identify sympathetic people when they are in our country,” he wrote in his autobiography. Turner rejected Harvard’s guidelines — as well as a Church Committee recommendation that the agency tell university presidents about clandestine relationships on their campuses — and made clear that the agency had no intention of following them.

If professors want to help the CIA, Turner argued in correspondence with Bok, it’s their right as American citizens. Harvard’s policy, he concluded, “deprives academics of all freedom of choice in relation to involvement in intelligence activities.”

The CIA promulgated its own “Regulation on Relationships with the U.S. Academic Community,” which remains in effect today. The one-page regulation ratified the status quo, permitting the agency to “enter into personal services contracts and other continuing relationships with individual full-time staff and faculty members.” The CIA would “suggest” that the staff or faculty member alert a senior university official, “unless security considerations preclude such a disclosure or the individual objects.”

Harvard and the CIA bickered with one eye on the audience they wanted to impress: the rest of academe. One university, no matter how prestigious, couldn’t stare down the CIA. But if other universities lined up behind Harvard, the agency would be hard-pressed to resist.

Halperin set out like Johnny Appleseed to sow the Harvard guidelines across the country. To his shock, the soil was barren. Other universities were reluctant to follow Harvard’s lead without documented evidence of covert CIA-faculty relationships, which the Church Committee had suppressed. University presidents wrote to the CIA, asking for particulars about cooperating faculty members, which the agency declined to provide. Some professors complained that Harvard’s rules would infringe on their academic freedom.

Only 10 colleges adopted Harvard’s policy even in diluted form.

Forty years later, Halperin remains perplexed. “I thought once Harvard did it, everybody else would follow,” he says. “Nobody did. It was a big disappointment. If we had been able to make it the norm on major campuses, it would have had impact. I was befuddled, bewildered, and frustrated. Finally, I just gave up.”

CIA moves to mend the breach with the universities

The CIA moved to mend the breach with academe. In 1977 it started a “scholars-in-residence” program in which professors on sabbatical from their universities were given contracts to advise CIA analysts and made “privy to information that would never be available to them on campus.” In 1985 the agency added an “officers-in-residence” component, which placed intelligence officers nearing retirement at universities at CIA expense.

The effectiveness of the officers-in-residence program was “very mixed,” said the former CIA analyst Brian Latell, who ran it from 1994 to 1998. Before he took over, he said, “we were sending Dagwood Bumsteads who should have been forced into retirement.” Some were just hanging around campus with nothing to do. Latell set standards; the officers must have advanced degrees and be allowed to teach. At its peak, the program had officers in residence at more than a dozen universities.

The CIA supplied not only teachers but also students, intervening in a cherished academic bailiwick: admissions. In some cases it arranged schooling for valuable foreign informants who were in danger and had to flee to the United States.

In other instances, the CIA compensated foreign agents by arranging their children’s or grandchildren’s admission to an American college and paying their tuition, typically through a front organization. “When you’re recruiting a foreigner, you look at, ‘What can I do for this guy?’ Sometimes a guy will say, ‘I want my daughter to go to a good American school,’ ” says Gene Coyle, who went to Indiana University as a CIA officer in residence. He retired from the agency in 2006 and is now a professor of practice at Indiana.

“The answer may be, ‘We may be able to line her up with a scholarship from the Aardvark Society of Boston.’ Instead of giving Daddy cold hard cash, when he has to explain where he gets it, his daughter gets the Aardvark Society second-born scholarship for people from Uzbekistan.”

While the CIA can pull strings at top universities when it needs to, some informants ask for less selective colleges. “We sent an awful lot of Arabs” to state universities in the Southwest, an ex-officer recalls. “They all wanted to study petroleum engineering. Those schools had a huge Arab population, and they fit right in.”

A generational shift underlies the increasing ties between the intelligence community and academe. Baby-boomer professors who grew up protesting the CIA-aided misadventures of the 1960s began to retire, replaced by those shaped by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the first Gulf War, and 9/11. Younger faculty members are more likely to regard the collecting and sifting of intelligence as a vital tool for a nation under threat and a patriotic duty compatible with — even desirable for — academic research.

Barbara Walter considers it a public service to educate the CIA. The political scientist at the University of California at San Diego gives unpaid presentations at think tanks fronting for the agency, sometimes for audiences whose name tags carry only their first names. When CIA recruiters have visited UCSD, she has helped them organize daylong simulations of foreign-policy crises to measure graduate students’ analytic abilities — and even role-played a CIA official.

She’s aware that some older faculty colleagues frown on those activities. “My more senior colleagues would absolutely not be comfortable consulting with the CIA or intelligence agencies,” she says. “Anybody who remembers or had exposure to the Vietnam War has this visceral reaction.”

Graham Spanier was the exception to Walter’s dictum. The Vietnam War didn’t prejudice him against intelligence agencies. As an undergraduate and graduate student at Iowa State University, he told me, he had been an “establishment radical.” Spanier, who had student and medical deferments and so didn’t serve in the war, led peaceful, law-abiding demonstrations against it but disapproved of confrontational tactics, such as taking over administration buildings. Once, when a march threatened to turn unruly, he borrowed a police loudspeaker to urge calm.

“I had the greatest respect for law enforcement,” he said. “I was always in the forefront of change, but I believed in working through the system. I wanted to be at the table, making change, rather than outside the building, yelling and having no effect.”

As he advanced in his career, gaining a seat at the table of administrators who hammered out academic policy, he paid little heed to the Church Committee or to CIA and FBI activities. Then, in 1995, he was appointed president of Penn State. Because the university conducts classified research at its Applied Research Laboratory, Spanier needed a security clearance. While he was being vetted, he read newspaper accounts linking a University of South Florida professor, Sami Al-Arian, and an adjunct instructor, Ramadan Shallah, to Palestinian Islamic Jihad, an Iran-backed terrorist group. Spanier was struck by USF President Betty Castor’s lament that she’d had no idea of Al-Arian’s alleged fund-raising for terrorists and that the FBI had not given her “one iota” of information.

The soft-spoken Shallah had been named head of Islamic Jihad and vowed war against Israel. The director of the international-studies center at USF was quoted as saying, “We couldn’t be more surprised.”

Spanier made his own vow: Never be surprised. As a university president, he thought, “I want to be the first to know, not the last.”

He convened a meeting in his conference room of every government agency that might conduct an investigation at Penn State, from the FBI and CIA to the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (the university does Navy research) and state and local police departments. “What I said to them is, ‘If there is a significant national-security or law-enforcement issue on my campus, you can trust me. I understand the importance and sensitivity of such matters. I would like you to feel comfortable coming to me to talk about it, rather than sneaking around behind my back.’ ”

They agreed to stay in touch. From then on, an FBI or CIA agent — usually both — would drop by once a month to brief him or ask his advice, typically about counterintelligence or cybersecurity issues involving foreign students or visitors. In 2002, David W. Szady became the FBI’s assistant director for counterintelligence. A quarter-century before, he had gone undercover at the University of Pittsburgh, posing as a chemist to befriend Soviet students. Now, like Spanier, he wanted to smooth relations between intelligence agencies and academe. Soon, FBI and CIA officials asked Spanier to expand the Penn State experiment nationwide.

|

The result was the National Security Higher Education Advisory Board (NSHEAB), established in 2005 with Spanier as its chairman. It consisted, then as now, of 20 to 25 university presidents and higher-education leaders, though some initially were nervous about their membership becoming public, fearing a campus backlash that never materialized. Spanier, conferring with the FBI and CIA, chose the members, primarily from prestigious research universities. At the FBI, Szady says, “nobody thought we could get it up and running,” because academe was perceived as hostile turf.

Board members receive security clearances and go to FBI and CIA offices periodically for classified briefings. The agenda for an October 2013 meeting at FBI headquarters, for example, included the investigation of Edward Snowden for leaking classified National Security Agency documents; the Boston Marathon bombing; Russian threats to laboratories and research; and Department of Defense-funded students abroad “being aggressively targeted” by Iranian intelligence. Afterward the FBI hosted a dinner for board members at a gourmet Italian restaurant in downtown Washington.

“There’s a real tension between what the FBI and CIA want to do and our valid and necessary international openness,” says one board member, Rice University’s president, David Leebron. “But we don’t want to wake up one morning and find out that there are people on campus stealing our trade secrets or putting our country in danger. We might be uneasy bedfellows, but we’ve got to find an accommodation.”

Spanier, the FBI and the CIA

The FBI and Spanier reached an understanding that it would notify him or the board about investigations at U.S. universities. In return for being kept in the loop, Spanier opened doors for the FBI throughout academe. He gave FBI-sponsored seminars for administrators at MIT, Michigan State, Stanford, and other universities, as well as for national associations of higher-education trustees and lawyers. Many of them arrived at his talks “with a healthy degree of skepticism,” he told me. Displaying his American Civil Liberties Union membership card to prove that he shared their devotion to academic freedom, Spanier would assure them that the FBI had changed since J. Edgar Hoover’s henchmen snooped in student files.

He also acted as a go-between for the CIA with university leaders who weren’t on the national-security board: “What a CIA person can’t do is call the president’s office, and when the secretary answers, say, ‘I’m from the CIA, and I want an appointment.’ It doesn’t work, and it’s not credible.

“Before anybody would do that, I would call the president,” Spanier continued. “The presidents all knew me. They would take my call. … I would say, ‘Someone from the CIA would like to come. There’s no issue on your campus now’ — occasionally there was an issue; most often it was a get-acquainted meeting. Sometimes I would just give the first name. ‘Someone will call your assistant; it’s Bob.’ … That worked 100 percent of the time.”

Spanier facilitated CIA introductions to the presidents of both Carnegie Mellon and Ohio State. A Pittsburgh-based CIA officer began visiting Jared Cohon, Carnegie Mellon’s president from 1997 to 2013, once or twice a year. “I know there was direct activity with selected faculty,” Cohon says. “They were interested in what the faculty might have observed when they went to foreign conferences. My impression, what I heard from the CIA, was that it was more defensive than offensive. Trying to make sure those faculty weren’t recruited by a foreign power.

“I was uneasy about it, and I am uneasy,” he adds. “I’m a kid of the ’60s, and I remember all the protests on campus. The idea of the CIA being on campus would have turned people crazy. Things have changed dramatically in that regard.”

Spanier frequently traveled abroad, visiting China, Cuba, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and other countries of interest to the CIA. On his return, the agency would debrief him. “I have been in the company of presidents, prime ministers, corporate chief executives, and eminent scientists,” he told me. “That’s a level of life experience and exposure you don’t have as a case officer or even a State Department employee.”

I asked if U.S. intelligence had ever instructed him to gather specific information — in other words, if he had ever acted as an intelligence agent. He smiled and said, “I can’t talk about it.”

His lofty contacts enabled Spanier to steer federal research funds to universities in general and Penn State in particular. When Robert Gates, who as president of Texas A&M University had been Spanier’s “close colleague” on the higher-education-advisory board, became U.S. secretary of defense, in December 2006, they brainstormed about academe’s role in national defense. The result was the Pentagon-funded Minerva Initiative, which supports social-science research on regions of strategic importance to U.S. security.

At meetings with the CIA’s chief scientist or the head of the FBI’s science-and-technology branch, Spanier invariably asked, “What’s your greatest need?” He rarely heard the answer without thinking, We can do that at Penn State. Then he would approach the director of the appropriate Penn State laboratory, explain what the CIA or FBI wanted, and say, “Why don’t you go and talk to them?”

Spanier resigned as Penn State president in 2011 and as chairman of the National Security Higher Education Advisory Board soon afterward, during a firestorm over child sex abuse by Jerry Sandusky, a former assistant football coach. University trustees hired Louis Freeh to investigate. He and Spanier had been friendly for years. Freeh was FBI director when Spanier welcomed the bureau to Penn State. In 2005, Freeh inscribed a copy of his memoir, My FBI, to Spanier with “warm wishes and appreciation for your leadership, vision and integrity.”

Freeh’s 2012 report portrayed Spanier quite differently. It accused him and others of concealing the child-sex-abuse allegations from trustees and authorities and exhibiting “a striking lack of empathy” for victims. Spanier denied the allegations and sued Freeh and Penn State separately, contending that they were scapegoatingd him. The university countersued. In March a jury convicted Spanier of one misdemeanor count of child endangerment for failing to report the abuse. In June he was sentenced to two months in jail, followed by at least two months of house arrest.

The CIA and FBI on Campus since 9.11

Thanks to Spanier, CIA and FBI agents could now stride onto campus through the main gate, with university presidents personally arranging their appointments with faculty members and students. But, except possibly at Penn State, they still slipped in through the back door whenever it suited them, ignoring their pact with Spanier that they would inform university leaders of their campus investigations.

For example, the FBI didn’t notify universities during the 2011 Arab Spring, when it questioned Libyan students nationwide, including Mohamed Farhat, a graduate student at Binghamton University, of the State University of New York.

“I’m a talkative guy,” Farhat told me. “I am very truthful. I don’t like hiding.” Married with three children — the eldest, a daughter, born in Libya, and two sons born in the United States — Farhat grew up in Zliten, a town about 100 miles east of Tripoli. He studied electrical engineering at a technical college, but it bored him, and he discovered that he had an aptitude for English. Within a few years he was teaching English at every level from middle school to college.

When Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, son of the dictator Muammar Gaddafi, decreed that the Libyan government would provide 5,000 scholarships for study abroad, Farhat seized the opportunity. He arrived in the United States in December 2008 and, after a year of English language study in Pittsburgh, enrolled at Binghamton.

As democratic uprisings sprouted throughout the Arab world in 2011, Farhat canceled his classes for the semester and joined cybergroups opposing the Gaddafi regime. There were about 1,500 Libyan students in the United States, and Farhat knew many of them. Soon friends began calling to let him know that the FBI had interviewed them, and that he, too, should expect a visit.

A worried Farhat contacted Ellen Badger, then director of Binghamton’s international-students office. She was accustomed to rebuffing FBI inquiries. When a university admits a foreign student or visiting scholar, it issues him or her a document required for a visa. It transmits the same information electronically to the departments of State and Homeland Security, but not to the FBI, which, unlike the other two agencies, has no regulatory authority over this population. Unless the FBI had a subpoena, under the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act she could provide only “directory information,” which includes basic student data, such as dates of attendance, degrees and awards, and field of study.

“There was a clear understanding they [the FBI] were going to chat with me in the friendliest way and would be happy with any information I could give,” Badger says. “I would respond in the friendliest way and give them nothing. That’s how the dance went.”

She reassured Farhat: The FBI would probably come to her first, and she would take care of it. Instead, the FBI bypassed Badger. Because the CIA was “somewhat blind” regarding on-the-ground intelligence in Libya, the FBI had been assigned to question students about the situation there, one insider told me. Agents were instructed to interview Libyan students off-campus, without alerting professors or administrators. To protect informants from exposure, the bureau wanted to be as discreet as possible.

An agent knocked on the door of Farhat’s apartment in a three-story brick building west of campus, showed identification, and said he wanted to schedule a time to talk with him. It never occurred to Farhat to refuse.

“I have no idea about rights,” he says. “This is not part of our culture. To me, the FBI are the ultimate power.”

Two agents showed up on the appointed morning. They sat at his kitchen table and unfolded a black-and-white map of Libya, asking where he was from. It was the first of five visits from the FBI, each lasting more than an hour, over a period of two months. The same local agent came every time, accompanied by one of two agents with experience abroad; one spoke a little Arabic. At the initial interview, they explained that they wanted to make sure that he wasn’t threatening, or threatened by, any pro-Gaddafi Libyans.

That mission reflected the bureau’s concern that, since most Libyan students in the United States were on government scholarships, some might be loyal to Gaddafi — and planning acts of terror against the United States for supporting the revolution against him. That worry turned out to be misplaced. “The students hated Gaddafi,” the insider recalled. “I don’t want to say it was a waste of time, but we satisfied ourselves that there was no threat from the Libyans.”

The agents proceeded to their other purpose: gathering intelligence. They asked Farhat about Libyan society and customs and his life from secondary school on. What disturbed him most were the questions about his and his wife’s friends and relatives, from other Libyan students to his uncles in the military. The agents wanted names, email addresses, phone numbers. Because they told him that they knew his email address and Facebook affiliations, he coughed up his most-frequent contacts, figuring that the bureau could track them anyway.

By the fourth visit, Farhat says, “I was annoyed.” The next time, he decided, would be the last. “I will tell them, ‘No more,’ ” he promised himself. As it turned out, he never had to muster the courage to defy them, because on the fifth session they wrapped up, then never returned.

Farhat didn’t tell Badger about the agents until afterward. “My reaction was regret,” she says. “What you want to do in a situation like this is make sure students are informed of their rights. They don’t have to answer any questions. They can decline a visit. They can set terms: ‘I want the director of the international office there.’ ‘I want a faculty member there.’ They have control.

“I never got to give that little speech.”

This is an expanded version of an article that appeared in The Chronicle Review.