Abstract

The first consciousness that a new Korean cultural wave –hallyu– was in motion began to take shape in different forms and at different times in the rest of East Asia. It was the craze for Korean TV drama that represented a sudden apparition of something new from South Korea. Before long, however, this wave grew bigger and far more complex than anyone might have predicted, including Korean pop music and films, animation, online games, smartphones, fashion, cosmetics, etc. There have been resistances to this inundation notably in Japan, a country where several earlier mini-hallyu now seem long forgotten.

Keywords

Hallyu, tv drama, Korean pop, manga, film

I want our nation to be the most beautiful in the world. By this I do not mean the most powerful nation. . . . The only thing that I desire in infinite quantity is the power of a noble culture. This is because the power of culture both makes us happy and gives happiness to others.

Kim Ku, Baekbeom ilji (1947)

Introduction

|

Kim Ku, 1876–1949 |

Kim Ku (1876-1949), in this rightly famous call to culture published not too long before his violent death, went on to articulate a vision of a Korea in which Koreans would not only be free for the first time in a long while to be Korean, but would as well project their culture out into the world. As he put it: ‘I wish our country to be not one that imitates others, but rather the source, goal, and model of this new and advanced culture. And in that manner, I wish our country to both initiate and embody true world peace. . . . In addition, the historical timing of all this at a time when we are engaged in rebuilding our nation is more than appropriate for fulfilling this mission. Indeed, the days when our people will appear on the world stage as the main actors are just ahead of us’ (Wikilivres).

There is a sense in which Kim Ku called it right, even though he could not have predicted how long or what form this would take. Nor would we feel comfortable associating a modern or post-modern concept such as ‘soft power’ with this veteran patriotic schemer and scrapper. It is, however, certain that Korea – at least South Korea – has over the past decade and more offered up a model for a new and advanced culture; that culture has brought a great deal of happiness to people in many parts of the world; Korean film-makers, TV drama writers and producers, and popular music producers have become main actors in the Korean wave phenomenon in its sweep through East Asia, Southeast Asia then on about the planet. And this is to say nothing about the actual actors, singers and dancers whose skill and physical beauty have captured the imaginations and hearts of millions of mainly but not exclusively young people who have never been to, who may never manage to get to, the nation which generated this propulsive cultural energy.

Obviously, a Korean of Kim Ku’s generation would not have had cinema, TV drama and certainly not K-Pop in mind when dreaming about a future ‘noble’ culture radiating from the peninsula. Still propelling Hallyu seems to be an uneasy mix of the old developmental drive for exports most associated with the Park Chung-hee era of the 1960-70s with a consumerist culture emergent only in the past few decades. Both represent eras of profound political/economic change as well as massive changes in culture as experienced, produced and consumed by most South Koreans. Were you to invent a time machine that could magically transport, let’s say, Girls Generation back before these epochal shifts, back even to 1947 Korea when Kim Ku was writing1, it isn’t difficult to guess that the reaction of a yangban audience to this long-legged example of singing and grooving might vary from incomprehension to outright fury (whatever their sons or daughters might be feeling). Perhaps the reaction would be more controlled, in the manner of the stunned silence of the Pyongyang elite when they were favored by a visit from the South Korean boy-group Shinhwa in December of 20122.

|

Girls’ Generation, founded 2007 |

Situating the Korean Wave

Of course the phenomenon of the Korean Wave existed before Chinese journalists coined a word for it around 1998 by joining the character for South Korea han 韓 with another which commonly indicates a trend, style, wave of popularity, 流. This generates a new word韓流 (Hallyu), one easily, visually understood all around East Asia, even on a hanja-resistant peninsula. The first consciousness that such a wave was in motion began to take shape in different forms and at different times in Japan, China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. For Chinese and Japanese commenters it was the craze for Korean TV drama that represented a sudden apparition of something new from South Korea. Before long, however this wave grew bigger and far more complex than anyone might have predicted twenty years ago: ‘it now includes a range of cultural products including Korean pop music (K-Pop), films, animation, online games, smartphones, fashion, cosmetics, food and lifestyles’ (Kim 2013). We could even add the very advertisements which are often significant propellants of the wave to its roster of cultural contributions.

In South Korea as well as in other capitalist countries, commercial advertising, while created as a sales tool, in its everyday circulation is distinguishable from other cultural products primarily by its form. Advertising draws on the same pool of cultural references, relies on the same mass media, casts the same celebrities, and engages the same audiences as other media. Advertising slogans find their way into public discourse, unusual advertising is discussed with acquaintances and blogged about, and advertising images animate fantasies and ambitions (Fedorenko 2014: 341-20).

It is striking that online and published CV’s of South Korea’s successful actors list, right after films appearances and TV drama roles, the best-known ads in which they have featured. That direct commercial connection is something generally played down, or passed off with irony, in the case of most American and European actors. (Of course, in the UK one short-hand term for people in advertising is ‘creatives’ – not a claim that goes unchallenged.)

|

Popular stars flogging stuff |

It seems as though a popularity first formed around visual culture – TV and film – is now born along in a tidal wave of consumer products to such an extent that it may seem difficult, if not reactionary or at least old fashioned, to attempt to extract some residue of the cultural from the flow of consumable commodities. Formulating an intellectual response to something so unexpected (and potentially ephemeral) as the Korean Wave can seem a daunting task. Here is how one eloquent interpreter, Youna Kim, sets out the research problematic:

Even the processes of contraflows [competing with dominant US popular culture] today, such as the Korean Wave, are multiply structured, mutually reinforcing and sometimes conflicting, while reconfiguring the asymetrical relations of power within a hybridization process. The emerging consequences at multiple levels – both macro structures and micro processes that influence media production, distribution, representation and consumption – deserve to be analysed and explored fully in an increasingly global, cosmopolitan media environment (Kim 2013: 3).

Kim herself is a British-trained , prolific writer on a wide range of Korean media. Her language is perhaps too finely tuned to internal debates within media/cultural studies and its professional idiolect to appeal to a general audience – or to ordinary surfers of the Korean Wave. But the energy and hard work she and other cultural interpreters are bringing to Hallyu give the patient reader some chance of grasping the significance of the accelerating conjunction of culture and commerce.

|

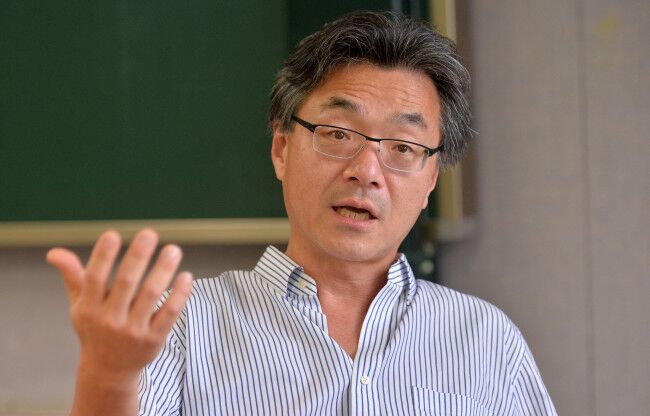

Professor John Lie |

Beyond cultural and media studies, Hallyu has attracted the formidable social scientific skills of John Lie. Lie’s previous works, such as Han Unbound, Multiethnic Japan and Zainichi, have established him as both a key political and cultural interpreter of modern South Korea as well as one of the most insightful guides to the experience of Japan’s Korean-origin minority, the zainichi – usually referred to in South Korea by the not altogether positive-sounding name of kyopo 교포. Lie has recently taken on what might seem to be the almost impossible task – perhaps especially for a fifty-something senior scholar (or so it must seem to this even older writer) – of understanding and contextualising the most intensely commercialised form of Korean Wave phenomenon, K-Pop. In so doing, he has dug back into the recent past of popular song in Japan, especially types of song such as Korean trot or Japanese enka, to remind us that Korean-origin and South Korean entertainers had gained an audience in Japan well before K-Pop stars such as BoA or the members of Dongbang Shingi were born.

Even if we exclude Zainichi singers, there were some South Korean trot stars – Yi Sŏng-ae, Cho Yong-p’il, and Kye Ŭn-suk among others – who were household names in Japan from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, the time of the boom in South Korean songs . . . Moreover, thanks to the karaoke boom of the early 1980s . . . personal renditions of South Korean trot songs became fashionable for Japanese businesspeople (Lie 2015: 113).

Of course, the 1970s or 1980s represent eras that to young people today must seem like cultural and technological dark ages, and older trot songs like something from an embarrassing past best relegated to the memories of grandparents and their dusty collections of LP records. Globally, it is only from around 1996 that music began to become available in digitized formats, and YouTube and competitors have only been around since 2005. It is not surprising that ‘South Korea [is] the first country where sales of digitized music exceeded sales of music in nondigital formats’ (Lie 2015: 119). For South Korean or English or Scottish teenagers, there’s always been a YouTube and downloadable music and video clips. The imaginations of South Korean youngsters – who perhaps rightly may themselves as having more in common with their European counterparts than their Korean elders – would be severely stretched to embrace a not so distant past when a largely rural population could hardly even listen to a radio – no electricity + no money = no radio – and where owning a record player was something most city kids could only dream about.

The earlier slow trickle of Korean popular music and musicians across to Japan was profitable for the entertainers and entrepreneurs involved. But the scale of K-Pop is altogether different. It has been estimated that in the single year of ‘2013, the government’s budget for promoting the popular-music business was roughly $300 million, roughly the same amount as total turnover in the industry a decade earlier’ (Lie 2015: 119). John Lie makes the case that it is not simply scale but the whole dynamic that is different. Unlike the Korean music of yesterday, ‘K-Pop has not been a demand-driven, quasi-organic development; rather, it has been the object of a concentrated strategy for its exportation’ (Lie 2015: 114). Within the music business, we can note the strategy by which Lee Soo-man and his now huge and diversified SM Entertainment invented singer BoA as cultural export for the Japan market. ‘SM Entertainment promoted BoA as a J-Pop star, one who just happened to be South Korean. The company hired leading Japanese voice and dancing instructors, investing £3 million in her debut’ (Lie 2015: 101). If you can’t beat them join them.

TV drama and resistance to the wave

|

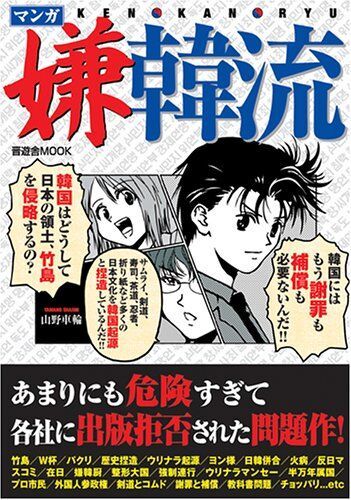

Manga Kenkanryu |

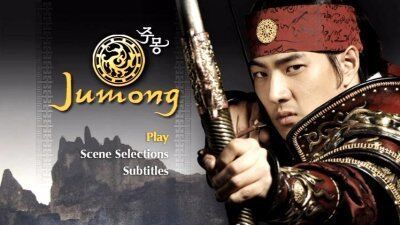

However, in the case of the Korean Wave, the result hasn’t been to so much to join with other markets of national pop cultural, as to seem to almost overwhelm them. This is of course one reason for the kind of negative reaction in Japan expressed with crude vigour in the best-selling series Manga Ken-Kanryū (Hating-Hallyu comic), one which cartoonist Yamano Sharin has stretched into four volumes between 2005 and 2015. One aspect of the reaction to the Korean Wave in Japan and China has been focused on the enormous popularity of Korean TV dramas. This reaction grew gradually from the early 2000s. Too many dramas on air for too many hours, has been the complaint of some social commentators. Some in China have, as is well known, reacted with less than enthusiasm to certain features of South Korean historical dramas. Take the case of one MBC favourite, Jumong, which ran for 81 episodes between 2006 and 2007. It has been sold to: Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Iran, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, The United States, and quite a few more countries. But China has not appreciated the way Han Dynasty figures are depicted as cruel and power-hungry, nor a story line that incorporates a large chunk of China’s Northeast – once referred to as Manchuria – into the Goguryeo kingdom; this was after all the same era in which the Academy of Chinese Social Sciences had been engaged in a massive research project, the Northeast Project (2002-07), destined to prove how integral the region was to China’s past and present. Efforts to broadcast the series in Hong Kong created controversy. The far-distant Han Dynasty is not the only source of Chinese villains dreamt up by Korean scriptwriters. The once much-revered Ming Dynasty provided a background, and some arrogant lecherous visiting Chinese officials, for the 2010 MBC series Dong-Yi4.

|

Jumong, 2006–7 |

Historical dramas (sageuk) are primarily targeted at an older audience. It was the success of melodrama and above all romantic melodrama and comedies that made Korean television series hugely popular in Japan and China, then all over the world. By now the 2002 KBS series Gyeol yeonga — ‘Winter Love Song’ but better known via its Japanese transformation as Winter Sonata – is the stuff of TV legend. It made its young stars, Bae Yong-joon and Choi Ji-woo, East Asian icons; this was especially the case with Bae, who probably cringes every time people evoke his Japanese nickname ‘Yon-sama’. Journalist Claire Lee, on the eve of the tenth anniversary of the series, recalled the Yon-sama phenomenon which followed the massive popularity of Winter Sonata in Japan during 2003-4:

Bae, who the New York Times called “the $2.3 billion man” for his value in 2004, made his famous visit to Japan that year. Some 3,000 middle-aged women gathered at Narita International Airport to greet their heartthrob. According to a scholarly article published on Keio Communication Review in 2007, some 350 riot police were there to guard the scene. In spite of the presence of the officers, however, 10 women were sent to hospital as they were injured from “pushing and shoving” in an attempt to see their “Yon-sama” (Lee 2011).

At a time when many Japanese young women were being criticised for devoting themselves to careers or enjoying foreign travel and shopping, or just generally daring to be independent rather than getting married early and producing babies to prop up Japan’s declining population, it was bad enough that young women swooned over Korean TV stars: they rubbed the insult to Japanese manhood in when observing that the Korean men were not only handsome, but also more manly – must be that military service which toughens them up, more than our hard-working but rather dull fellows. But then the mothers got in on the act, and had enough disposable income to catch the plane to Seoul, to following in their thousands the TV drama trail to Nami Island – key location for Winter Sonata – and then come home and start studying Korean! The bitterness of slighted masculinity has provided fuel for some fairly silly publications such as the Ken-Kanryū comics. It may even have been one element motivating the notorious Zaitokukai, the quasi-fascist hate-group targeting zainichi and other foreigner residents in Japan. When life seems a bit complicated and full of people different than you, blame it on Yon-sama.

|

Japanese female fans greet Bae Yong-joon |

The changing fortunes of TV production as an export were themselves a kind of drama. Twenty years ago, in 1996, Statistics from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism indicate that South Korea imported US£42.2 million worth of TV programmes and exported barely US$ 5.5 million. In the wake of the take-off in TV series in Japan and elsewhere that occurred a decade later, the 2005 figures present a very different picture: imports up to US$ 31.0, but exports increased by almost twenty-fold to US$ 100 million (Shim 2008: 27). Compared, for example, to the export figures for Samsung the same year, those are small potatoes. But the increase in the export of South Korean culture was just about to add music and music videos to the mix, eventually the most profitable of all cultural exports. The year Winter Sonata aired in South Korea, 2002, the domestic market for popular music was estimated to be worth something like US$ 296 million. That, too, sounds like a lot, until you compare the relevant estimates for Japan that year, US$ 5.4 billion (Lie 2015: 116). No wonder that SM Entertainment or Park Chin-yong’s JYP Entertainment saw the neighbouring market as crucial for export breakthrough, on their way to conquering as much of the world as they could get to. By one accounting, K-Pop exports reached US$235 million in 2012: the Japanese market accounted for US$ 204 million of the total (Wikipedia [Eng]: K-Pop).

The Normalization Treaty and the mini-Hallyu of the past

|

The Same Starlight on This Land, 1965 |

Yoshinaga/Mochizuki Kazu with Korean orphans |

South Korean scholar Yang Inshil has unearthed an interesting mini-Hallyu, more a ripple than a wave, that we might regard as testing the waters for what was to come in later decades as regards both film and TV drama (Yang 2007). It occurred in Japan in the context of the major rapprochement achieved by South Korea and Japan through the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea signed in June of 1965. (For a recent overview, see Lee 2011). In that year director Kim Kiduk – the older Kim Kiduk – already known for his skills in genre film and for his commercial instincts, made a film about an extraordinary Japanese woman, Yoshinaga Kazu (also known as Michizuki Kazu). It had the long title The Same Starlight on This Land (<이땅에도 저별빛을>)3. She had ended up in Seoul at the outbreak of the Korean War and took it upon herself to rescue and care for orphans swept up in the chaos. She was made an honorary citizen of Seoul in 1964, and the next year her personal story became a bestselling book. Kim seized the double occasion of the treaty signing and the story of one remarkable Japanese individual to produce a bio-pic released in October the same year. It starred the most famous omoni (grandmother) in Korean cinematic history, the great Hwang Jeong-sun, who died last year at the venerable age of eighty-eight. It may be difficult to recall that this was an era in which film representations of Japanese characters were almost always two-dimensional, cardboard villains. To cast Hwang as a Japanese woman was a bold, clever move. The film was released in Japan the next year under the title Love Crossing Borders, and made a considerable impact, once again due in part to the context of the treaty. In Japan it had stirred some opposition, but never aroused the furious reaction of South Korea’s protestors of the troubled era. This is a case of one South Korean film, made by a South Korean director with staff and cast all Korean, being a modest success – by telling the story of a Japanese woman!

Yang Inshil has noted that in order to find a similar Korean wavelet in the realm of TV drama means waiting until the early 1980s. A 1981 KBS special drama was shown the same year in a late-night slot on Japanese television. The title was Yumi’s Diary. Unlike the sentimental route through the mothering central character of Kim Kiduk’s film, this drama treated the shocking story of a zainichi school boy, Im Hyeon-il. Hyeon-il took his own life in 1979, frustrated by bullying and discrimination. In an unusual step, the South Korean government staged his funeral as a state occasion. I don’t know what the particular forces were, political or other, which led the Chun Do-hwan regime to host the funeral; we might assume that it was an attempt to assert the regime’s legitimacy, after the massacre at Gwangju. I assume that it was old-fashioned Japanese liberal regard for zainichi and other minorities which got the drama on television, even if relegated to an 11.00 p.m. slot. You can only wonder if it could happen now given the current chilly climate between the two countries. Yang points out that the drama, by narrating Hyeon-il’s story through the figure of his older sister, manages to at least partially feminize and sentimentalize the harsher aspects of the story and the real, continuing contradictions and injustices of zainichi life in Japan.

Diaspora

Korea’s greatest export has been, since at least the mid-nineteenth century, Korean people. First the small groups and families trickling over the border with Qing China, attempting to leave behind the harsh taxation and arbitrary rule of late-Joseon Korea; then the late-1860s famines pushed more people, especially from northern provinces such as Hamhung over into the Russian far east. As Japanese forces intrude into the country from the time of the suppression of the Donghak Rebellion of the mid-1890s to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, the exodus of poor farmers is joined by disaffected Koreans of all classes. Some will end up in China or Russia, some try to get to the United States. Japan’s control of the borders makes the slender life-line to US cities for intellectuals, or to the cane fields of Hawaii for the poor, harder to make use of. In the early decades of the mid-twentieth century the land of the free would erect insurmountable racial barriers before immigrants from the East. Japan would attract, then eventually force, several million Korean workers to Japan to augment a workforce depleted by conscription of Japanese workers to fight the never-ending war in China and then the deadly war through the Pacific Islands.

Some 600,000 descendants of this single largest diasporic group remain in Japan. A roughly equal number make up the Chinese-Korean joseonjok population, many of whom now form a source of mainly low-paid labour in South Korea and Japan. What had been a vigorous Korean community of over 170,000 people in the Soviet Union’s Primorski krai/Maritime Province was loaded onto boxcars during the autumn of 1937, driven straight through the freezing weather into Central Asian, dumped off in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan and left pretty much to fend for themselves. Thus did Stalin – basking since the previous year 1936 in a orotund new title, ‘the Father of Nations’ – dispose of his people.

The biggest, fairly recent change in the diaspora concerns the Korean-Americans. It was only with the final removal of racial quotations in the mid-1960s that this group of highly motivated communities really began to take shape. By the 1980s Korean-Americans famously, or infamously, were regularly included in that condescending term of praise for Asian Americans, ‘model minority’. Koreans Americans have played a part in the Korean Wave: as singers and actors, as musicians, artistic advisers and promoters, and business contacts for Korean entrepreneurs and performers trying to crack the US market. One of SM Entertainment’s ‘first stars, Hyǒn Chin-yǒng, was a Korean American. Especially in the 1990’s, a steady stream of Korean Americans . . . began returning to South Korea’ (Lie 2015: 60; see also Russell 2008: 133-65). Others, of course, might come to South Korea in order to explore family roots, to study Korean, or to land a job in an economy that seemed to be booming. As significant as this American connection has been, below I want briefly to consider the role of one key member of the zainichi diaspora in the diffusion of South Korea’s new cinema.

Yi Bong-u and the cinematic wave

After leaving behind his home in Kyoto and studying in Paris for two years in the mid-1980s, Yi Bong-u had become a devoted cinephile. It would take some doing but by 1989 he had set up his own distribution company. He traveled to the great European film festivals and brought back films to the Japanese arthouse audience by the great Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski, by radical British film-maker Ken Loach, and even our beloved British animation, Wallace and Gromit. By 1993 he had moved into film production. He worked with fellow zainichi director Choi Yang-il (Sai Yōichi) to create the first really popular film about the experience of zainichi and other minority people, All Under the Moon (Tsuki wa dochi ni dete iru?).

|

Seopyeonje, 1993 |

Around this time he heard about a film that was breaking box office records in South Korea.

Im Kwon-taek’s small, intimate film about an odd family of wandering pansori singers – Seopyeonje – had stirred something profound, it seemed, in the newly democratizing country. At a time when the film industry was deep in the doldrums, overwhelmed by American imports and its own mediocrity, a veteran director had wagered that a literary adaptation exploring a disappearing form of Korean musical culture might just sell some tickets. Although only screened in a few cinemas, Seopyeonje became the first Korean film to attract more than one million viewers. Thanks to the generosity of the Korean Film Archive, you can go to YouTube and judge for yourself.

Hearing that the film might be screened at the Cannes Film Festival, Yi Bong-u flew to France only to discover that Im had changed his mind about the screening. Luckily, someone was there from the Korean Film Council with a version on VHS. Yi was stunned by the beauty of what he saw and heard. Back in Japan he faxed the production company, eager to acquire the Japanese rights. He was desperately eager to fly to Seoul and make the deal with Taehung Pictures before some other distributor got there. Which is when things started to get really complicated. Because the generally apolitical Yi Bong-u comes from an important family in the North Korea-affiliated organization usually referred to by the short name Sōren/Chongryeon. He had neither a Japanese nor a South Korean passport, but travel papers good enough for European countries. At the Korean Embassy in Tokyo it took him several days to persuade staff to issue a temporary visa – he was granted all of three days. So a Saturday came when off he went, to find himself met at the airport by officials of the security service. They ushered him through a diplomatic channel and drove him straight into the city. By this point Yi was having doubts about the wisdom of following his passionate attachment to Seopyonje.

He was taken to the Shilla Hotel and given a thorough questioning, both as to his purpose in coming and concerning his family’s history which, disturbingly, they knew in great detail. Once they had left him alone, Yi dashed off to meet Im’s producer Yi Tae-won. The story had a more than happy ending. After an all-night drinking session with the formidable Mr Yi, he flew back to Japan Sunday morning with his contract, scrawled on a scrap of paper (Lee & Omota 2005: 269-76). Yi Bong-u went on the bring films such as Swiri (1999), Park Chan-wook’s JSA (2000), Yi Chang-dong’s Oasis (2002) and Bong Joon-ho’s real breakthrough film Memories of Murder (2003), to Japanese screens. The impact on serious film-goers, Japanese critics and film-makers was extraordinary.

I would argue that films such as these represent a Korean Wave that is thankfully still lapping at our shores. Films by the three directors mentioned above are recognized as landmark achievements in the creation of a South Korean cinematic culture, one which blends high artistic standards, technical virtuosity and popular appeal. Yi Bong-u, from his often uneasy position within the Korean diaspora, set something in motion which, I believe or at least hope, will prove of more lasting significance for global culture than all the clips on YouTube ever could.

Retro-elegy

John Lie, who I have quoted from throughout this essay, notes with wry humour a comment of Gustav Mahler: when it comes to debates about musical taste, ‘the younger generation is always right’ (Lie 2015: 17). Yes, they probably are. I would like to end with one last passage from Lie’s very fine book K-Pop. In it I think he eloquently captures the bemusement of older generations confronted with their tech-savvy children and grandchildren. He is speaking about music but what he says holds true for youth culture in general. (It also creatively recasts the famous closing line of The Great Gatsby.)

The urge to seize the moment valorizes the present and the new, contributing in turn to the devaluation of the past and the traditional, which in any case is suspicious precisely because of its association with parents and elders. The perpetual modernity of the popular-music canon goes hand in hand with a constant forgetting of the past. Youth’s discretionary spending power and the constant transition of the generations ensure that popular music beats on, borne ceaselessly into the future (Ibid.)

Readings

Fedorenko, Olga (2014) ‘South Korean Advertising as Popular Culture’, in The Korean Popular Culture Reader, eds. Kyung Hyun Kim and Youngmin Choe (Durham & London: Duke University), pp. 341-62

Kim, Youna (2013) ‘Introduction’, in The Korean Wave: Korean Media Go Global, ed. Youna Kim (London: Routledge), pp. 1-27

Lee, Claire (2011) ‘Remembering ‘Winter Sonata’, the start of hallyu’

Lee Bong-u & Omota Inuhiko (2005) 「パツチギ!対談篇」 (Tokyo: Asahi Books)

Lee Jung-Hoon (2011) ‘Normalization of Relations with Japan: Toward a New Partnership’, in The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea, eds. Byung-Kook Kim & Ezra Vogel (Cambridge: Harvard Univ Press), pp. 430-456

Lie, John (2015) K-Pop: Popular Music, Cultural Amnesia, and Economic Innovation in South Korea (Oakland: Univ of California)

Russel, Mark James (2008) Pop Goes Korea: Behind the Revolution in Movies, Music, and the Internet Culture (Berkley CA: Stone Bridge Press)

Shim, Doobo (2008) ‘The Growth of Korean Cultural Industries and the Korean Wave’, in East Asian Popular Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave (Hong Kong: Univ of Hong Kong Press), pp. 17-31

Wikipedia [Eng]: K-Pop

Yang Inshil (2007) ‘韓流の前夜’, in 2007 Trans: Asia Screen Culture Conference (Seoul: Korean National University of Art), pp. 127-29

Notes

This is not to suggest that Kim Ku was excessively straight laced. Bruce Cumings notes that when he finally returned to Korea from China, ‘Kim . . . traveled around with a “bevy of concubines” and a “flotilla of gunmen”’ (Cumings 1997: 197). The trajectory of Kim’s life was deeply inflected by Japan’s conquest of Korea. It took him from youthful student of the Confucian classics to Donghak rebel; after several spells in prison and the experience of torture, he became a member and eventual leader of the Korean Provisional Government in exile, based in Shanghai. Before and after his leadership of the KPG, his resort to political violence earned him the nickname ‘the Assassin’ (Ibid: 197-8). That makes it somewhat disappointing to see that the actor portraying him in the recent historical political thriller The Assassination (2015) only has a very minor role. A life that fairly begs for big-screen treatment has seemed to produce only dull hagiographies such as the stodgy 1960 film Aa, Baekbeom Kim Ku Seonsaeng.

This film, like a surprising number of films from the not so distant past, no longer exists except in the form of a scenario. During the 1960s heyday of South Korean cinema, the government restricted the number of prints that could be circulated, generally to six. The ostensible reason was to limit the outflow of capital, in this instance, money needed to buy raw film stock from overseas. As films moved from first-run theatres in cities to second- and third-run venues, to towns and smaller towns, the prints grew more and more fragile, often with badly made repairs and splices. Films were seen as commodities the value of which dropped rapidly once screened in any given theatre, whose owners would be anxious to get the newest release on the screen. Few people in the business really seem to have considered film as having lasting cultural value and worth careful preservation. Now, South Korea has in the Korean Film Archive one of the world’s most significant institutions for the preservation and restoration of visual culture.

One nasty-looking fellow even assumes he will bed our fair young heroine Dong-Yi, played wittily and with seductive virginal charm by Han Hyo-ju. Like other men of a certain age who watched and worried over Dong-Yi through all 60 episodes, I can testify that there was no way he was going to get away with that.