This is the second of a two-part article. Part one, entitled “The ‘Japan Is Great!’ Boom, Historical Revisionism, and the Government” by Tomomi Yamaguchi, is available here.

Abstract: What I refer to as “Japan-Is-Great” materials are “consciousness products” (Bewusstseins waren) in which “Japan” and “Japanese people” are praised and held out as special for their wonderful historical, cultural, or ethical qualities, and as excellent on a global scale.1 This class of products has now spread through the Japanese media ranging from books, magazines, and mooks; to television, radio, and government-sponsored programs; and furthermore, to human resources seminars and various types of courses on culture.

Most notably, “Japan-Is-Great” variety shows have been produced at the public broadcaster NHK and at almost all private television stations, so many people have seen or heard their self-praising frolicking. It is striking that almost all stations started airing these programs between 2012 and 2014, coinciding with Abe Shinzo’s second term and the “Cool Japan” strategic formulation (2012) advanced by that administration.

Many “Japan-Is-Great” books have also appeared. The shelves of bookstores are lined with “bestsellers” with titles full of admiration for Japanese such as Japanese Acclaimed by the World and Why Japanese Continue to Be Respected Worldwide. All of them are essentialist and ethno-centric notions of Japanese culture expressed through catch phrases such as “pride in being Japanese” and the “splendor of Japanese culture.”

Teacher, Japan Is Great, Isn’t It?

The epitome of this trend is the book Teacher, Japan Is Great, Isn’t It? Live Coverage of Classroom Excitement (Takagi Shobo, 2015) by Hattori Takeshi, a social studies teacher at a public middle school in Kanagawa Prefecture. It is essentially a list of “Japan-Is-Great” stories that have been extracted from modern history.

|

Hattori Takeshi, Teacher, Japan Is Great, Isn’t It? (Takagi Shobō, 2015) |

One aspect of the book that sets it apart from others, however, is that it is a record of Hattori’s “moral” education lessons. Moreover, the teaching materials that have been chosen are full of anachronisms that can hardly be conceived of as appropriate for school textbooks in the 21st century. The majority of the historical figures lived prior to Japan’s defeat in the “Great East Asia War.” We have stories about the “Japanese army dispatching Siberian troops to help exiled Poles,” “Major General Higuchi and Colonel Inuzuka helping the Jews,” “Wills left behind by Kamikaze (Tokkō tai),” “Hatta Yoichi loved by the Taiwanese,” “Japanese saving the passengers of the shipwrecked Ottoman frigate Ertuğrul (1890),” and “Captain Sakuma” and “Uesugi Yōzan.”2

As a record of lessons, student impressions of each episode are included. These, too, are shocking. For example, for “The Showa Emperor and MacArthur,” Hattori relates that Emperor Hirohito tells MacArthur that he is responsible for everything and then asks the students, “What do you think about what the Showa Emperor did as the leader of the Nation?” The student responses to this question were “great.”

“I think we must be truly thankful to the Showa Emperor. I feel we must cherish the Nation of Japan.” “I thought, ‘Wow, even the fact that I am alive now is thanks to the Showa Emperor.’” “Just as I expected, the Showa Emperor was a very great man.” “I thought that the Japan of today exists and I myself am alive now thanks to these great people who have protected Japan.” Such voices attempting to outdo one another in interminable accolades for Japan appear throughout the book.

This book seems to be gaining popularity in the group “Lesson-planning JAPAN” formed by teachers who participated in a former Jiyūshugi Shikan Kenkyūkai. (The “Association for Advancement of an Unbiased View of History” is the official name in English, but it is also often translated as the “Association for the Advancement of a Liberal View of History”). Based on this lesson record, classes are conducted and seminars are held on how to plan lessons.

In fact, the form of discourse in which historical fables roll out one after another throughout Teacher, Japan Is Great, Isn’t It? is extremely popular in other “Japan-Is-Great” books.

If one includes not only publications by ordinary publishing houses such as Kō Bunyū’s Japanese Admired by the World (Sekai kara zessan sareru Nihonjin, Tokuma shoten, 2011) and his Japanese Who Made the World Weep (Sekai wo gokyū saseta Nihonjin, Tokuma shoten, 2012), which tops the list; Shirakoma Hitomi’s Impressed! Japanese History—How Japanese Lived through Adversity (Kandō suru! Nihon shi—Nihonjin wa gyakyō wo dō ikita ka, Chūkei shuppan, 2013); and Onagi Zenko’s Japanese Who Were Great Both Then and Now (Mukashi mo ima mo sugoi zo Nihonjin!, Saiun Shuppan, 2013) but also the works of various conservative groups such as “Biography Series for Children” put out by the educational organization New Educators Federation (Shin kyōikusha renmei), which is an anti-mainstream branch of [the new religion] Seichō no Ie (“house of growth”), and Urabe Kenshi’s (1950~) Tales of Japanese Resurrected beyond Time-space that is put out by a self-improvement organization called the Institute of Moralogy (Morarojī kenkyūjo), then there are clearly a sizable number of such books being published.3

Hattori writes in his “Afterword” to Teacher, Japan Is Great, Isn’t It?, “In our country there have been many great predecessors and examples, and just by relating the facts as they are, [children] experience excitement.” He also writes, “The excitement brings about the purification of evil things in [a child’s] heart. When one makes contact with a beautiful life, values that one could call the “aesthetics” of action gradually sprout up in the hearts of pupils.”

“The purification of evil things in one’s heart” can no longer be categorized as a “moral” education class at a public middle school.

Conservative and right wing organizations have for some time focused their energies on breaking into the market of public primary and middle school teaching materials for “moral” education classes through their discourse of “Japan Is Great,” mixing in plenty of historical revisionism.4 They are on the verge of calmly and quietly reviving material of the likes of Captain Sakuma, who played an important role in “moral training” under the Japanese Empire, thereby creating a tool to produce “good Japanese.”

Desire for a Story about the “Japan-Is-Great” Nation

As for me, this book must not be imagined as the final form of the “Japan-Is-Great” materials.

In fact, the method of selling “Japan Is Great” by accumulating historical fables and anecdotes one after another has been around for a long time. In teaching materials on history in Japan prior to Defeat, the method of speaking about “National History” through a mechanical listing of fables about loyal retainers, righteous gentlemen, sons and daughters notable for their filial piety, and chaste women was fully exploited in state-sponsored, history textbooks and primary-school readers for Japanese language classes. Fables and legends were employed in order to deepen understanding of the history of the nation through empathy for the characters presented, and also as teaching materials [in order to represent] a model morality for the nation.

The person who pioneered this indoctrination through legends to fit our present-day conditions was Sakamoto Takao (1950-2002), a board member of the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (Atarashii Rekishi Kyōkasho Wo Tsukuru Kai, founded in December 1996, often abbreviated as “Tsukuru Kai”). For Sakamoto, history education should “aim to nurture consciousness of the Nation,” and he theorized it as a “story of the Nation” that would “respond to the question of how to unify the people.”5 What most faithfully applies this “story-of-the-Nation” method is the “Japan-Is-Great” materials in the style of historical fables. A prime example of such materials is Hattori’s Teacher, Japan Is Great, Isn’t It? The historical revisionist dimension of conservative groups in Japan has been closely analyzed, and the fake history that results from mechanically listing fables continues to manifest itself as the “story of the Nation.”

No longer can one talk of “Japan-Is-Great” materials as something merely functioning at the level of entertainment. An ideology reformulated over a 20 year-period that spreads a “consciousness of the Nation” is knocking at our door.

The Period of the Great Flood of “Japanism”

Once previously, after the Manchurian Incident of 1931, the publishing industry flooded the country with “Japan-Is-Great” patriotic books. Historian Akazawa Shiro found that the “momentum was such that one sees a tendency for books and editorials that preach Japanese spirit and Japanism to begin to dramatically increase in 1933, and by 1934, one finds ‘two or three new publications with titles like Japan Spirit Such and Such appearing every day without fail’ in the ‘newly arrived titles column’ in newspapers.”6

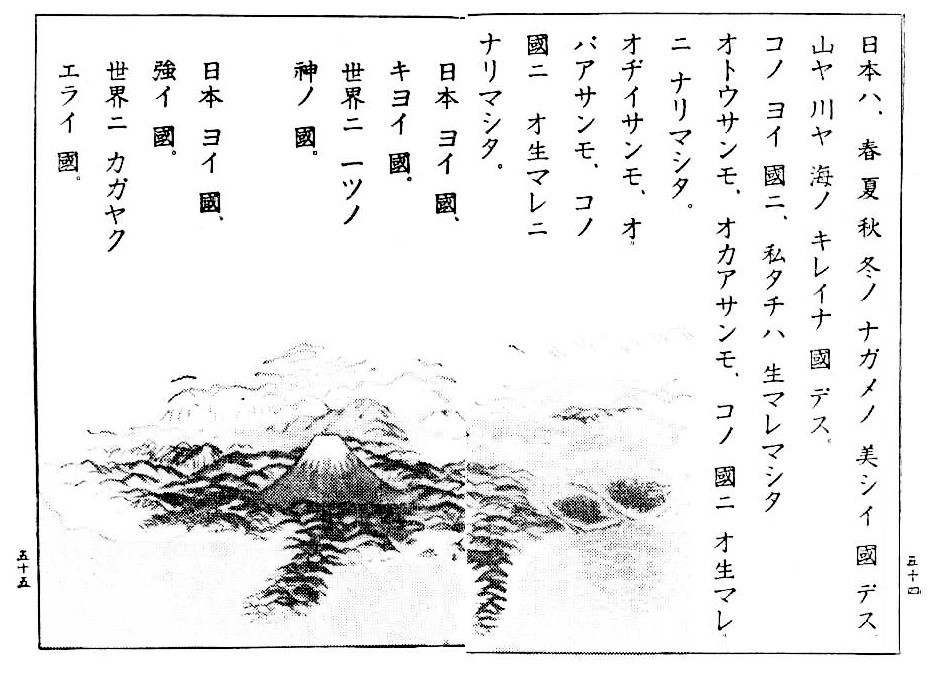

|

“The Japanese Nation,” from the second volume of Good Children, a textbook from the fifth stage of state-sponsored textbooks. Students in the second grade of primary school used this textbook. The message “Japan, the good country, the pure country, the one and only land of the gods” can be seen in the “Japan-Is-Great” discourse of today. Image provided by Hayakawa Tadanori. |

Only a few years after this “spirit of Japan” publishing boom started, the Second Sino-Japanese War became a full blown war and the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement (Kokumin Seishin Sōdōin Undō) started. After cultivating the spiritual soil as the subjects of his majesty’s country, people accepted all-out war and proceeded to actively bear the burden of that War.

The “Japan-Is-Great” materials of 70 years ago began with “divine possession,” and ended with “divine possession.” What had been the nonsense of some anachronistic people was raised to the level of state theological refinement. That ended up bringing about the universal conviction that “Japan is and always will be undefeated” (Nihon fuhai), and in the end led to the ruin of the Japanese Empire.

Related article

Shirana Masakazu and Ikeda Teiichi, Japan is Great.

Notes

In 1910 an accident occurred involving the Number 6 Submarine of the Japanese Navy. All fourteen members of the crew perished, but wills were drawn up just before they died. Captain Sakuma’s will appears in “Composure and Courage,” the sixth chapter of the state-sponsored textbook Primary School Moral Education (Jinjō shōgaku shūshin) during the Second Period; in “Composure and Courage,” the sixth chapter [of the state-sponsored textbook] Primary School Moral Education (Jinjō shōgaku shūshin) during the Third Period; and in “The Will of Captain Sakuma,” the third chapter [of the state-sponsored textbook] Primary School Moral Education (Shotōka shūshin) during the Fifth-Period. [Hatta Yoichi (1886-1942) was an engineer who contributed to hydraulic engineering in Taiwan when it was a colony of Japan. The full name of “Captain Sakuma,” 1879-1910 was Sakuma Tsutomu. “Yōzan” was the pen name of Uesugi Harunori, 1751-1822].

[Kō Bunyū (1938~) is a controversial Taiwanese author, who lives in Japan and has been accused of promoting Japanese neo-nationalism. See http://apjjf.org/-Matthew-Penney/3116/article.html Advertisements about the writings of Shirakoma Hitomi (1965~) can be found at http://www.dokusume.net/hitomi/index.html Onagi Zenko (1956~present), Urabe Kenshi (1950~present). The New Educators Federation website is at http://www.shinkyoren.jp/ The Institute of Moralogy’s site is at http://moralogy.jp/].

For instance, the same sort of fables and anecdotes about the will of Captain Sakuma and Uesugi Yōzan that appeared in the aforementioned “Moral Education” textbook appear [once more] in Moral Education Textbook for 13-Year-olds and Above edited by the Experts Group (Yūshikisha no Kai) that promotes moral education (Ikuhōsha Publishing Inc., 2012).

Akazawa Shiro, Thought Mobilization and Religious Control in Modern Japan (Kindai Nihon no shisō dōin to shūkyo tōsei, Azekurashobō, 1985).