|

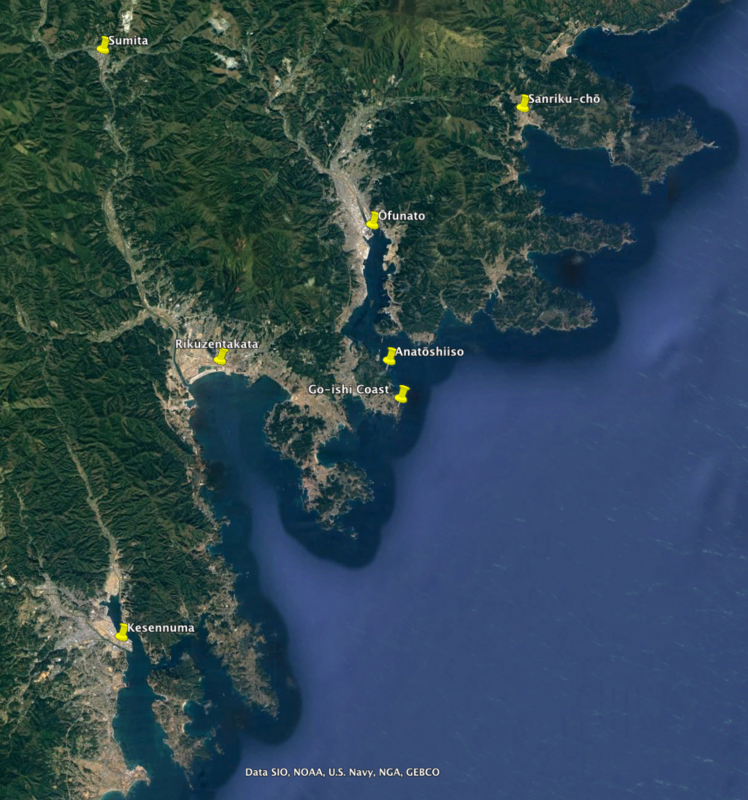

Map of Japan. Map data from Google. |

Abstract:

The city of Ōfunato is located in northeastern Japan, in the southeastern portion of Iwate Prefecture. It lies on the Sanriku coast and is a fine example of a ria coastline with several prongs of mountainous ridges that extend outward into the sea. The coast is home to Iwate’s largest port, and houses several well-developed industries, including industries related to fishing, marine products processing, and cement production.

The impact of the 3.11 triple disaster of earthquake, tsunami and nuclear power meltdown is told here in visual images and the poetry by Arai Takako.

Ōfunato and the 2011 disasters

The city of Ōfunato is located in northeastern Japan, in the southeastern portion of Iwate Prefecture. It lies on the Sanriku coast and is a fine example of a ria coastline with several prongs of mountainous ridges that extend outward into the sea. The coast is home to Iwate’s largest port, and houses several well-developed industries, including industries related to fishing, marine products processing, and cement production. On the outskirts of the city limits are Anatōshiiso and the Go-ishi Coast, which because of their dramatic rock formations and islands, are well known for their natural beauty. Ōfunato is home to approximately 40,000 people.

|

Anatōshiiso. The name of this site means “pierced rocky shoreline.” Photo by the author, June 2016. |

|

Go-ishi Coast. The name comes from the fact that the small islands look like stones used in the game of go (go-ishi). Photo by the author, June 2016. |

|

Map of the Kesen region, which straddles Iwate Prefecture in the north and Miyagi Prefecture in the south. Map data from Google. |

Ōfunato, along with the city of Rikuzentakata and the town of Sumita, are part of what is known as the Kesen Region. The speech used there has a high degree of regional distinctness and is known as Kesengo (literally “the language of Kesen”). In fact, there is an increasing push, which has been spearheaded by Yamauchi Harutsugu, a medical doctor who lives in Ōfunato, to have Kesengo recognized not just as a minor dialect of Japanese, but as a distinctive language with its own rich history and tradition.

Ōfunato suffered tremendous damage during the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011. According to the website of the Ōfunato Municipal Government, a quake just shy of 6.0 on the Richter Scale was recorded downtown and the nearby areas, and soon afterward, a devastating tsunami of approximately ten meters tall assaulted the coastline.1 In Sanriku-chō, one outlying area of the city, the tsunami reached the staggering height of twenty-three meters. The commercial district in the center center of Ōfunato was destroyed, and the rest of the town was left seriously damaged.

By December 2016, at the time when this article was completed, the official death count from the 2011 disasters was 15,893 people dead, 2,556 people missing, and 6,152 people injured.2 Of those, 340 of the dead and 79 of the missing came from Ōfunato.3 2,791 households were completely destroyed, but if one were also to include the numbers of houses that were classified as “partially destroyed,” then the number of households that sustained damage rises to 5,582.4

About a month and a half after the disasters, I visited the city of Kesennuma, located in Miyagi Prefecture, a bit to the south of Ōfunato. I was there to help clean up earthquake-ravaged homes, but the destruction that I witnessed there is difficult for me to put into words even now, after all of this time.

|

Kesennuma soon after the disasters. Photo by the author, May 2011. |

|

Kesennuma soon after the disasters. Photo by the author, May 2011. |

Years have gone by since then. Rubble is still being removed throughout the region, and the ground beneath laid bare. Earthen mounds are being constructed, and large enterprises are moving ahead with plans to construct facilities for commercial use. Homes are being rebuilt, and victims placed in temporary housing are still in the process of trying to find permanent housing elsewhere. According to the Iwate Prefectural Reconstruction Bureau’s Division of Living Support (Iwate-ken Fukkō-kyoku Seikatsu Shien-ka), as of March 2016, there were still 1,691 people in Ōfunato living in temporary housing—a total of 781 households. Fortunately, through various efforts, this number had decreased by November 2016 to 808 people living in temporary housing—a total of 359 households.5

|

Meeting room at one of the temporary housing facilities in Ōfunato. Photo by the author, November 2014. |

My first trip to Ōfunato was in November 2014, a little more than three and a half years after the disasters. I had been making plans with the Museum of Contemporary Japanese Poetry, Tanka, and Haiku (Nihon Gendai Shiika Bungakukan) located in the city of Kitakami in Iwate Prefecture to start a project that we had labeled, “Words to Stir the Heart: The Voices of Ōfunato.” The plan was to go around to the meeting rooms in the temporary housing facilities and work with the local people to translate the tanka poems of the poet Ishikawa Takuboku (1886-1912) into the local language of Ōfunato—into Kesengo, in other words. As some readers may know, Takuboku is one of the great tanka poets of modern Japanese literature. He was a native of Iwate Prefecture, but his poetry was written in the language of modern Japan—the kind of increasingly standardized Japanese that would come to be seen as the language of the Japanese citizen. In other words, he wrote in Nihongo, “the language of Japan,” not Kesengo “the language of Kesen” or any other dialect. In working with the inhabitants of the temporary housing and their neighbors to translate Takuboku into Kesengo, our project aimed to help participants rediscover the unique charm of the language of the northeast and to help share that more broadly with the rest of Japan. As of December 2016, the “Words to Stir the Heart” project has held nine meetings, and we have reached the initial goal of translating one hundred different tanka into Kesengo. We are currently moving forward with efforts to publish them in book form.

Each time I visit, I see the changes in the city. The hotels in the center of the town, which were rapidly patched up after the disasters, have been completely rebuilt one after another. At the same time, people are criticizing the current plan to erect embankments against future floods, saying that the embankments are too large in scale. What should be the relationship between nature and mankind? Between the sea and humanity? The debates rage on.

|

Reconstruction near the port of Ōfunato. Photo by the author, November 2014. |

|

Reconstruction near the port of Ōfunato. Photo by the author, February 2016. |

Disaster poetry by the poets of Ōfunato

The Ōfunato Poetry Society

One of the big benefits of this project was that through it, I got to know many poets living in Ōfunato. While drinking beer together, enjoying ochakko (which is Kesengo for “snacks”), and riding with them in their cars, we talked about all sorts of things—not just the disasters, but also our families, our jobs, our poetry, and the culture and customs of the Kesen region. They are now the strongest supporters of our “Words to Stir the Heart” project, and one of the reasons that I now look forward to heading up to the northeast is because I want to see them again. In the remainder of this essay, I would like to introduce some of the poetry written by Ōfunato poets about the disasters. All of this was material that I discovered through working together with them on our project.

Japan is a big place—it might sound silly for me to say this, but when I encountered the work of the Ōfunato poets, that is one of the things that struck me. Their work is almost completely unknown in Tokyo and elsewhere, if it is known at all. Over the last few years, there have been many people speaking and arguing about the role and language of poetry produced in times of disaster. We’ve seen popular journals and literary magazines taking up those questions. There have been anthologies of disaster-related literature. Sometimes they feature local poets from the northeast, but I feel that I only gained a real sense of what they were doing when I met the Ōfunato poets in person.

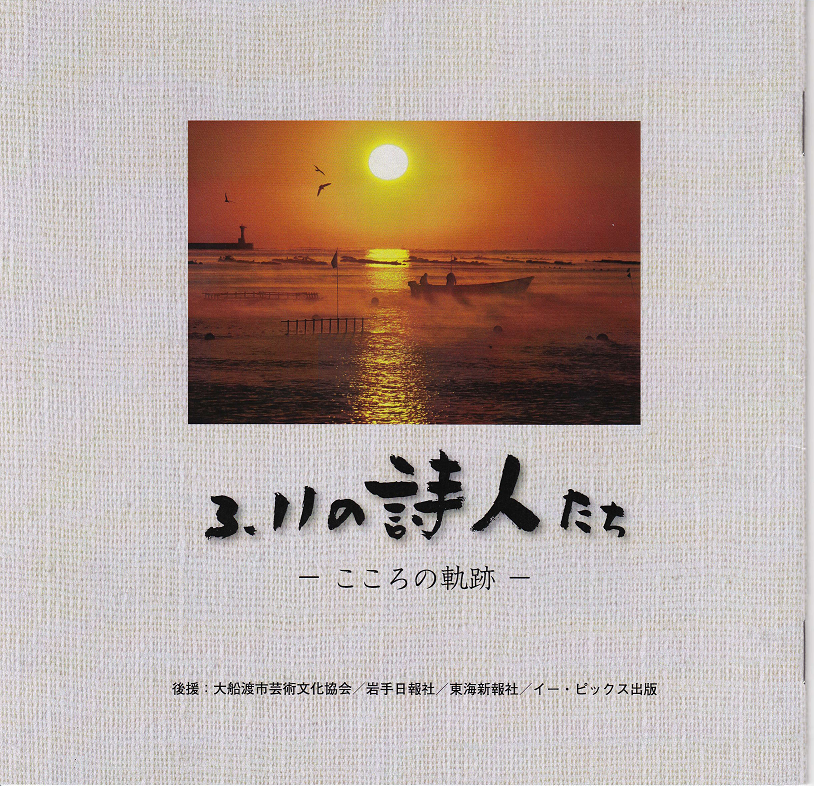

The first time we met for the project, we met in Okirai, Sanriku-chō. We held our event in the Sugishita Temporary Housing Complex. I was in the common room, putting away the CD player afterwards when someone handed me a booklet and said, “Please read this.” It was Nomura Miho, one of our participants. The title of the booklet was The Poets of 3-11: The Locus of the Heart (3.11 no shijin-tachi: Kokoro no kiseki), and it was published by an organization called the Ōfunato Poetry Association (Ōfunato Shi no Kai).6 In it, I found Nomura’s poem “Daffodil” (Suisen). Here it is in both an English translation and the original Japanese.

|

小さな白い水仙を 赤い南天の実にそえて活ける 部屋が暖かくなってくると ほどけるように 香りが広がってくる 水仙は 地中海沿岸が原産国という シルクロードを旅して 東アジアに渡って 日本の浜辺に たどり着いたのだろうか 三、一一 あの未曾有の災害にも耐え抜いて 厳寒の空の下 緑の葉を凛と伸ばし 可憐な白い花びらの中に 金の盃を抱き その盃に 陽光が満ちるように 輝く幸せに 溢れるときが 必ずやって来るだろう |

I place a small white daffodil Alongside a sprig of nandina covered with red berries As the room grows warm Their aroma spreads As if unravelling They say the daffodil Comes from along the Mediterranean coasts I wonder if it travelled Across the Silk Road To East Asia Reaching the coasts of Japan March 11 The flower made it through this unprecedented disaster Beneath the bitterly cold sky It grew its green leaves with so much dignity And now holds in its dainty white petals A golden cup Surely a time will come When that cup Will overflow With sparkling happiness As if filled with sunlight |

|

|

| The Poets of 3-11: The Locus of the Heart, edited by the Ōfunato Poetry Association. | Figure 1: Nomura Miho |

I was taken by surprise. I hadn’t realized that among the participants in our project there would be poets who wrote their own original works. This poem, describing the petals of a flower embracing a beautiful little cup, impressed me. I felt as if a sudden burst of light was washing the scales from my eyes.

And then, there was the remarkable poem “My Goodness, You’re Alive…” (Igide da gaa) by Kinno Yukie, in which she reproduces the kinds of conversations one heard after the disaster, all in the local Kesengo language. (The following English translation doesn’t attempt to render the dialect into any specific dialect of English, but I encourage readers interested in hearing the incredible musicality and intonation of the original to listen to the sound file. In it, Kinno reads her own work.)

|

Figure 2: Kinno Yukie |

|

あんだー 生きてたがぁー 熱い抱擁で涙する 家も無(ね)エ 部落も無エ 体一つだ なんにも無エ あんだー パンツと靴下けらい お握り一つ パン一つ 有難ァぐ食ってる この歳で一から出直しだぁ うん、うん うん 冷たい手を握りしめて あんだばかりで無エ 命あったべ 命あったんだから 頑張っぺえ なぁ! なぁ! なあ! |

You… My goodness, you’re alive… We weep in a warm embrace We’ve got no homes, no village Just our own bodies, nothing else You Give us some underpants and socks A single rice ball, a single loaf of bread We’ll eat them gratefully We’re starting all over at this age Yeah, yeah… That’s right We take one another’s cold hands You’re not alone You’re alive, right? We’re alive So let’s keep going Yeah! Yeah! That’s right! |

The warm blood of life seems to be flowing through these words. All along the coast, when people found one another immediately after the disaster, they would greet each other with the words, “You… My goodness, you’re alive…” (Andaa… Igide da gaa…) as in the first lines of this poem. Reading between the lines, one senses the shadows of the 20,000 people who were not able to mutter these words. I was also struck by the powerful phrase “Give me some underpants and socks” (Pantsu to kuzusuta kerai). In this one, condensed phrase, one senses how desperate the situation was for all those people who managed somehow to escape the tsunami with nothing more than their own bodies and the clothes on their backs.

Kinno Yukie, the same poet who wrote the poem I just quoted, wrote the following poem entitled “God” (Kami-sama) in response to the Catholic church’s public call for prayers. Once again, Kinno writes in the vivid, local dialect—an important strategic choice that allows her to quite literally give voice to the battered and dispirited people throughout the region.

|

津波の時 おらの命助けてくれて有難う 放心状態の空っぽの命 これからなじょすればいいんだ 砂浜におかれた蟻んこのようだ 右も左も東も西も何もわかんねぇ 親戚の人は四人死んだ おらなじょすればいいんだ 教えてけろ 息吐くたび 助けて助けてと無言の声が鼻から出て行く 神様 おらに何しろといってるんだ わかんねぇ わかんねぇ もっとぎっちり側にくっついてけろ ぎっちりくっついて教えてけろ わらすに語るように教えてけろ せっかくもらった命だもの 大事にすっから教えてけろ 大事にすっから教えてけろ |

Thank you for saving me when the tsunami came Saving my empty, absent-minded life But what am I supposed to do now? I’m like a tiny ant on the sandy beach I don’t know my left from my right, my east from my west Four of my relatives are dead What am I supposed to do? Tell me With each breath Unspoken voices pour from my nose–Help! Help! God What are you telling me to do? I don’t get it, I don’t get it Come closer and stay by my side Stay by me and tell me Tell me as if you were speaking to a child After all, I’ve been given this life I’ll take good care of it, so tell me I’ll take good care of it, so tell me |

In the breath that flows from the narrator’s nostrils, she hears the cries of the dead calling out for help. She hears and understands their silent plea, but is at a complete loss as to what to do. She calls out to God, hoping that he will come closer, almost as if she hopes that his proximity and direction will keep her from being carried away by the spirits of the deceased. This poem teaches us that the spirits of the dead seem to be lodged deep within the bodies of the surviving, moving aimlessly through them. The dead are within the living. In the disaster zone, the dead and the living are together in visceral ways.

Nakamura Sachiko and Tomiya Hideo

As we planned the second meeting of our project, we sent some a flier and a letter to Kan Chieko, the head of the Ōfunato Poetry Association. She came to the Sawagawa Temporary Housing facility where we held our meeting, and there introduced me to Nakamura Sachiko, who had been in charge of editing the booklet that I had received on my previous trip.

Nakamura, known by her nickname “Sat-chan,” is of the same generation as I am. Since we first met, I have spent time with her on almost every one of my trips to the northeast. She married when she was quite young, gave birth to three children, and is already a grandmother. She sees the real world in a cool-headed way, and in her gaze, I sense calm maturity.

Nakamura told me that when the members of the Ōfunato Poetry Association wrote the works that were collected in The Poets of 3-11, everyone was united in their desire to preserve the dignity of the dead. The mountains of rubble and refuse everywhere were, in fact, also cruel piles scattered with corpses of the local residents—the same people that were their relatives, friends, and neighbors… Each one of the poets was clear that they didn’t want to sully the memories of those deaths. As they wrote their work and published the booklet, no doubt they were keenly aware of the friction that arises between writing about something and laying bare for all the world to see something that they cared about deeply.

The coast of Akasaki-chō in Ōfunato is known for oyster cultivation, and Nakamura, who worked in that industry with her husband’s parents, referred to the sea as a “field” (hatake). The tsunami, however, had destroyed their oyster beds, and after deliberation, her father-in-law had decided to give up the business. She told me that the painful decision came as her own father was in the hospital dying. She describes the circumstances in her poem “Alongside a Certain Death” (Aru shi no katawara de).

|

震災のさなか ようやく長い夜が明け 父は旅立った 選ぶことも 選ばないこともできずに ひとり残された私は 混乱と疲労の病室で 息を殺していた 慰安室は 次々と運ばれてくる犠牲者のためにあり 止まったままのエレベーター トリアージを待つ行列 避難者で溢れるロビー 電話も車も使えない 一時間で戻ると約束して その変わり果てた町を いくつもの悲しみの中を 無言で歩く 海と陸の境目に残った 地震で崩れた部屋に 薄い布団を敷き 真新しいシーツで包み 写真立てを捜して 約束の時間はとっくに過ぎていて だらだらと続く坂道を上り 町を見下ろす病院の 五階の奥の つめたい父の頬に触れて いつになるか分らない という死亡診断書のために 薄暗い階段を下りて また上がっては下りて 昨日と変わらないはずの 外界の眩しさに戸惑い 思えば 誰もがみな喉がからからで 遺族の悲嘆も 空腹に泣く幼子たちも 自然あいての戦場の 膨れ上がる雑踏に紛れてゆく わたしはまだ 取り残された死の傍らにいる |

Right in the middle of the disasters The long night finally came to an end My father set out on his journey Unable to choose Unable not to choose either Left behind all alone In a hospital room of turmoil and exhaustion I held my breath The mortuary room Was for the sacrificial victims brought in one after another The elevator was still stopped A procession waiting for the triage The lobby overflowing with refugees Neither telephones nor cars working I promised to return in an hour I walked without a word Through the utterly transformed town Through so much sadness In a room ruined by the quake At the border of the sea and land I spread out a thin mattress Wrapped up a brand new sheet Looked for a stand for the memorial photo It took much longer than the hour I said I’d be gone I walked up the long, gently sloping street And in back of the fifth floor Looking down over the town I touched my father’s cold cheek I went down the gloomy staircase For the death certificate That would be issued who knows when I climbed up and down the stairs again Confused by the brightness of the outside world Which must have been no different than yesterday Come to think of it Everyone was completely thirsty The grief of those who were left behind And the cries of the hungry children Get lost in the crush that swells up On the battlefield with nature Still I am alongside Death left behind |

Unable to get a death certificate in the midst of so much confusion, the body of her father grows colder and colder; meanwhile, the bodies of the people killed by the tsunami are carried in one after another. Moreover, the hospital was running so desperately short of materials that they asked family members of the victims to bring sheets to wrap the bodies of their loved ones. It is difficult to imagine writing this poem unless one actually lived through the disasters oneself. In her volley of crisp words, Nakamura conveys the weighty importance of time as she deals head-on with her own grief and that of the town where she lives. As she pushes the jumble of objects in her disordered room to the side and spreads out some bedding, she prepares the sheet which she will use to wrap her father’s body. The image of the fresh, new sheet in the midst of so much confusion is striking.

The water supply did not work for many days. In one of her e-mails, Nakamura told me soon after the disasters, everyone was thirsty so they collected rainwater and drank it with great relish. Even if they did come in contact with one of the vehicles that traveled through the region to update residents and share information, their radios were just broadcasting information about evacuation centers and safety concerns. She said that they didn’t know a thing about the meltdown taking place at Fukushima. That was the situation that everyone was in when she writes, “Come to think of it / Everyone was completely thirsty.”

Below is one stanza of Nakamura’s poem “Seeds of Tomorrow” (Ashita no tane), which appears in a small collection called Songs of Support for Sanriku’s Recovery (Tachiagaru Sanriku e no ōenka).7

|

暗黒の街を 最初に照らしたのは 信号機だった まじめに 明るく 馬鹿正直がいいと 声が聞こえた(後略) |

The first thing to illuminate The dark town Were the traffic lights Soberly Brightly Honest to the point of foolishness I heard someone say […] |

The power was out of course. Every light in the center of Ōfunato was broken, plunging the town into a series of pitch-black nights. As the poem says, the first lights to come back on were the traffic lights… The narrator recounts overhearing someone talking about the traffic lights performing their job soberly, brightly, and in a fashion that is honest to the point of absurdity. There is darkness in this, perhaps even irony.

Nakamura also writes novels and children’s literature. She does not only write about her personal experiences. She is a writer with a real ability to bring together scraps of news and documents to form narratives. Her story “The Bear of Mt. Nametoko and Matsuyoshi” (Nametoko-yama no kuma to Matsuyoshi) which appeared in Issue 66 of the literary journal Literature of the North (Kita no bungaku) gives a fresh and elaborate portrait of a hunter, and is a richly rewarding read.8 I feel incredibly fortunate to have suddenly come across a writer like her during my trips to Ōfunato.

|

Tomiya Hideo |

I would like to introduce one more poet from the Ōfunato Poetry Society, Tomiya Hideo. One of his essays appears in the collection Neckties and Edo-mae (Nekutai to edo-mae), edited by the Japan Essayist Club. Subsequently, his home and the house he rented out—both of which were located close to Ōfunato Port—were lost to the tsunami.9 There have been big changes in the lives of everyone in the region, but Tomiya’s life underwent a particularly severe and dramatic transformation. After the disasters, he lived in temporary housing in Sakari-chō, where he continued writing, but he earned his livelihood by clearing rubble and working nights at a health center for senior citizens. After years living in temporary housing, finally in the autumn of 2016, he moved into a public building created for the disaster victims, and there, he has finally been able to embark on a more stable, comfortable life.

Below is an excerpt from his poem Toward Tomorrow (Ashita ni mukatte).

|

津波で流された自宅跡 初めて見た時 不思議と涙は出なかった 両親の位牌さえ持ち出せず かろうじて助かった命 でも亡き両親が救ってくれたと思う お盆の墓参りで不思議な現象を目撃した 以前の地震で少しずれていた墓石が 大地震で元通りになっていたのだ 環境が変わると生き方も変わる 避難先を親戚宅からカメリアホールへ移して 避難所で多くの人たちと知り合えた喜び 盛小学校の仮設住宅に決まり 引越し前夜は最後の避難者になった たった一人で大広間に泊まった心細さ 大きく変わった人生観 がれき撤去の仕事に就いて 夏の暑さにも冬の寒さにも耐えながら ペンよりも重いものを持ったことがない私が スコップを手に働いている 甥や姪たちにとって私はヒーローなのだ(中略) これ以上のどん底はないから 後は希望を持って前へ進むだけなのだ(後略) |

When I first saw what little was left Of my home washed away by the tsunami Strangely, I didn’t shed a tear Unable to carryout my parents’ memorial tablets I barely escaped with my own life But I think it was my dead parents that saved me During the Bon Festival, I witnessed something odd Our gravestone, which had shifted during a previous earthquake, Returned to its rightful place when the big one came Change environments and your life changes too When I moved my refuge from a relative’s home to Camelia Hall I felt such joy at finding so many friends there They decided to use Sakari Elementary School as temporary housing I was the last evacuee left the night before the move Such loneliness sleeping there in the large hall all alone My views on life changed so much I took a job clearing rubble As I suffered through the summer heat and winter cold I, who had never held anything heavier than a pen, Worked with a shovel in hand To my niece and nephew, I was a hero […] There are no depths lower than this So the only thing to do is hold out hope and keep moving forward […] |

Some time ago, Nakamura, Tomiya, and I had dinner together at a Chinese restaurant. He took our hands in his and said, “It’s been decades since I held a flower in each hand.” I couldn’t help thinking what a kind man he is, but with a small show of embarrassment, we apologized saying, “Sorry we’re such dried up flowers.” After participating in the second meeting of the “Words to Stir the Heart” project, Tomiya wrote warmly about that night in an essay he published in the Tōkai News (Tōkai shinpō). That evening too, as we were having beers together, he spoke encouragingly about our project saying, “The people that stayed on afterwards said that they found it really interesting.” But then he suddenly changed the subject. With a smile lingering unchanged on his face, he told us, “I’ve been diagnosed with depression.”

In his poem, Tomiya mentions the abject depths to which he has fallen. It is difficult for me to ascertain exactly all of the feelings that are contained within the word “depths”… In fact, when I first read The Poets of 3-11, I found myself thinking that perhaps if more of the lines didn’t conclude with words like “hope” (kibō), “smiles” (egao), and “hang in there” (ganbaru), the poems would be more interesting. After all, I am a writer, and as I read, I find myself slipping into those questions about the craft of writing—avoiding stereotypical language and the like… However, as I got to know these writers and found myself developing a relationship little by little with Ōfunato, even if only as a visitor to the region, I began to realize the depth of feeling and implication that was contained in these relatively commonplace words. If anything, I was the one who was not able to appreciate the depth that they contained. When Tomiya speaks about needing hope, he reflects the depression, hopelessness, and desperation he feels. Only after meeting him could I begin to understand that it was precisely because he was feeling such boundless despair that he turned it around and dared to speak of hope. With this realization, I began to understand how essential it was for people like him to hold on to the idea that there would be a recovery one day.

Meeting Kinno Takako

Nakamura introduced me to another poet as well, Kinno Takako who belongs to another poetry group in Ōfunato known as the Akane Poetry Society (Akane Shi no Kai). (She is not related to Kinno Yukie, the poet mentioned earlier.)10 In August 2015, she self-published a book of poetry entitled Kerria Flowers (Yamabuki).11 When she contributed to the Kesengo translations in our “Words to Stir the Heart” project, she did so with such vigor that I had assumed that she was probably in her seventies, but when I saw the biographical note included in her book of poetry, I was surprised to find that she was older than that—she was born in 1932.

|

|

| Kerria Flowers by Kinno Takako | Kinno Takako |

Kinno’s father was one of the first people to cultivate oysters at Akasaki-chō Aza Atohama along the seashore, but because he passed away at a young age, her mother worked to support her through needlework and other small jobs. Because she is so deeply rooted in the area, Kinno grew up to become what we might call a “bilingual” poet—fluent in Kesengo and standard Japanese. (When she speaks with her close friends, I can barely understand a word.) Kinno worked for nearly thirty years as a nursery school teacher in Akasaki-chō. Perhaps because she spent much time reading to the children, but she has rich experience with the world of books, and takes great pleasure in tanka poetry. Below is an excerpt from the poem “The Slope to the Fields” (Hatake e no sakamichi) in her collection Kerria Flowers.

|

戦中戦後の食料難の時代 母は畑を耕した 庭先に南瓜 丘の畑にはさつまいも 馬鈴薯 瓜 母は農家に生まれたが 畑仕事には慣れていなかった 〈肥やし いっぺぁしねぁば いい作ぁ出ねぁがら〉 母は私を相手に肥桶をかつぎ 坂道を畑へと往復した 背の高い母と父親似の小さい私 桶の中で揺れだす肥 肩の痛さ 惨めさ 恥ずかしさ なぜか笑ってしまった 後ろから母の大声 「なにぁ おがし あるげ」(後略) |

During the food shortages during and after the war Mother tended the garden Just outside were pumpkins On the hill were sweet potatoes, potatoes, and melons Mother was born into a farming family But wasn’t used to working in the fields “If you don’t give it tons of fertilizer You won’t get a good crop” Mother and I carried buckets of night soil between us on a pole Back and forth on the sloping street to the fields Mother was tall, I was short like Father The refuse splashed out of the bucket My shoulders ached, I was miserable and ashamed Still for some reason, I laughed From behind, Mother spoke loudly “Is something funny?” […] |

When I was a little girl and I visited the home of my grandmother on her farm, did it smell of night soil? In any case, when she was a girl, she had to carry buckets filled with excrement on a pole over her shoulder. We can sense in the poem how much the swinging buckets affected her feelings. She writes, “My shoulders ached, I was miserable and ashamed / Still for some reason, I laughed.” I can’t help but think that the fact that she began writing her own creative work had to do with that personality—she was the type of girl who laughed when she was miserable, and would remember that laughter for years to come. In other words, she is a person who keeps her feet on the ground, yet she has so much energy that she seems ready to take a gigantic leap from wherever she happens to be.

Not long ago, after one of our “Words to Stir the Heart” meetings, I went with Kinno to have lunch at the home of one of her friends who had just moved from the temporary housing erected after 3.11 to public housing supported by the prefecture. As we were talking, Kinno said that in the old days, they had to work hard to prepare their meals, feeding the flames of the stove with sticks. As she said this, she puffed up her cheeks, imitating the act of blowing through a tube of bamboo to feed oxygen to the fire. She recalled the days soon after she left home to start a new life as a wife. She recounted how a touring choir came to perform in Rikuzentakata City. She wanted so desperately to go hear them that she left her infant child with her own mother and set off to go listen to them. Although she initially said to me, “Honestly, I’m not even sure why exactly I wanted to hear them so much,” I pressed her further. It seems that one reason for her enthusiasm was that she wanted to hear the “standard” Japanese (Nihongo) she was learning in school put to practical use.

Let me share a poem that she wrote in Kesengo about the 3.11 disasters. The title is “The Day We Saw Spring” (Har-ar mēda hi). The English translation doesn’t try to reproduce the dialect, so once again, I encourage readers interested in the sounds of Kesengo to listen to the sound file.

|

なんだべ がれぎの中さ 黄色い花っこァ咲(せ)ァでだ なんと 水仙の花っこだがァ こんなせまこい間っこがら ゆぐ顔(つさ)っこだしたなァ あの三月の大津波ァ 平和な暮らしばさらってすまった それがらずものァ なにもかも止まった がれぎの山ァ 言葉も涙も止めだ 空では雪ばりふらせで 季節のめぐりまで止まったど思った そしたれば なんと 小(ち)せァ手っこさ春のせで だまァって動いでだものァ いだったんだねァ 泥水で固まった土ば 押しあげて 押しあげて 花っこ咲がせだ水仙 おらの 眼(まなぐ)ァひかってきた 胸でば大ぎくひろがって がれぎの果でまで叫(さが)びだがったァ おらァ春みだァ しっかどみだァ *せまこい=狭い、ゆぐ=よく、ばり=ばかり、 みだァ=見た、しっかど=しっかりと |

What’s this? In the rubble A small yellow flower blooming My goodness A small daffodil It’s done well to bloom here In such a small spot The huge tsunami in March Completely washed away our peaceful lives And then after that Everything stopped The piles of rubble and refuse Stopped even our words and our tears The sky dropped nothing but snow I thought that even the turning of the seasons had stopped But my goodness, even in the midst of that Something was silently moving Taking spring into its small hands The daffodils bloomed Pushing up, pushing up Through earth hardened by filthy water My eyes Begin to glisten My heart begins to swell I want to shout to the farthest edge of the rubble I’ve seen spring I’ve seen it for sure

|

The first line of the poem, “What’s this?” (Nan da be) suggests that the narrator is squatting down and looking down. There, barely emerging from the rubble, is a daffodil, which blooms as if not missing a beat. This poem reminds me of the poem by Nomura Miho, quoted earlier—after the disasters, it was these small yellow flowers, filled with light, that announced the coming of spring to the citizens of Ōfunato.

Each time I listen to the participants in our workshops read their translations of Ishikawa Takuboku in their local language, I am struck by the sounds of Kesengo. Of course, there are many voiced consonants (dakuon), but the language is also rich in resonance. In lines like “A small yellow flower blooming” (Kīroi hanakko-ar sear deda) or “Something was silently moving” (Damātte ugoide da monar), Kinno sometimes extends her vowels with a small a(r) sound, which she represents with the katakana symbol ァ and which lends an emotional complexity to the line. In poetry, we sometimes talk about reading in the space between the lines, but here, she has created a space between the individual letters themselves, and in that space, we sense her emotion. In that space, the narrator seems to take in a feeling of wonder, and at the same time, mouths it slowly, clearly so that the reader can take partake of it as well. Through those seemingly small sounds, the look of the poem on the page and the sound of the words seem to waver slightly, as if one is looking at a vision through shimmering currents of air on a hot day. In the final lines, “I’ve seen spring / I’ve seen it for sure” (Orār haru mi dār / Shikkado midār), the narrator directs her gaze toward the vision of the daffodil. The sound and meaning of this beautiful poem work so well together that it is almost as if the entire poem is itself one gigantic onomatopoeia.

Although this has only been a whirlwind tour, this essay gives a brief introduction to the work of some of the local poets whom I met in Ōfunato. I hope that you will obtain copies of their booklets and anthologies to read for yourselves. It seems to me that the disaster-related poetry that they wrote differs significantly from that written by more mainstream poets in the Tokyo region. (I should know. I am one of the many poets living in central Japan who wrote about the disasters.) In their work, reality precedes rhetoric. Still, their work is different than what we think of when we imagine realism. Yes, their work is real, but even more than that, their work is rare and raw. What do we find there? How should we take it in? Their work challenges us in many ways.

With its dramatic cliffs and inlets, the seashore along Ōfunato is spectacularly beautiful. If you look out over the landscape on a clear day, it is so beautiful that it hardly seems it could belong to this world. I will never forget what Iwabuchi Fumio, a master ship carpenter told me during one of my visits. Iwabuchi lived in Kesennuma and lost everything, both his home and his workplace, to the tsunami. Even so, he told me that he hoped I would carry within me, “the heart of the sea.”

Notes

NOTES: This is a revised version of an essay that first appeared as Arai Takako, “Ōfunato nōto,” Mi’Te: Shi to hihyō, Vol. 134 (Spring 2016). Ōfunato-shi, Higai jōkyō nado, See here (accessed 28 Dec 2016).

Keisatsu-chō, Heisei 23-nen (2011-nen) Tōhoku chihō Taiheiyōchū jishin no higai jōkyō to keisatsu sochi, See here (accessed 28 Dec 2016).

Ōfunato-shi, Higashi Nihon Dai Shinsai ni yoru higai jōkyō nado ni tsuite (Heisei 28-nen 9-gatsu 30-nichi genzai), See here (accessed 28 Dec 2016).

Iwate-ken Fukkō-kyoku Seikatsu Saiken-ka, Ōkyū kasetsu jūtaku (kensetsu bun) kyōyo oyobi nyūkyo jōkyō (Heisei 28-nen 11-gatsu 30-nichi genzai), See here (accessed 28 Dec 2016).

Ōfunato Shi no Kai, ed. 3.11 no shijin-tachi: Kokoro no kiseki (Ōfunato-shi: E-Pix Shuppan, 2012). Readers interested in ordering a copy should contact the publisher at TEL 0192-26-3334.

Sanriku o Yomō Jikkō Iinkai, ed. Tachiagaru Sanriku e no ōenka (Ōfunato-shi: Sanriku o Yomō Jikkō Iinkai, 2014).

Kita no bungaku, vol. 66 (May 2013). This journal is published by the Iwate Nippōsha, the publisher of the Iwate Daily News (Iwate Nippō).

Nihon Esseisuto Kurabu, ed., Nekutai to Edomae: 7-nenhan besuto essei shū (Tokyo: Bungei Shunju, 2007).

In the city of Rikuzentakata, located next to Ōfunato, there is a mountain called Tamayama Kinzan, where gold ore was first discovered in ancient times. As a result, the surname “Kinno” (meaning “gold fields”) is common in the region.