While the high drama of the Brexit vote and the U.S. presidential election has grabbed international headlines, Japan has quietly completed an election that may also have far-reaching implications. In the elections for the Upper House of the Diet (Japan’s parliament) on July 10, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its coalition partners won 162 seats, which, together with Diet seats not up for election and the seats of sympathetic but unaffiliated members, give the coalition a two-thirds majority in the Upper House. It already had a two-thirds majority in the Lower House.

A two-thirds supermajority in both houses is the threshold needed to initiate a revision to Japan’s Constitution, pending approval by a majority of voters in a referendum. This Constitution has never been amended since its inception in 1947. Since it was a product of the Allied Occupation, the ruling LDP has wanted to change it since the party was founded in the 1950s—an aim shared by the current prime minister, Abe Shinzō. The possibility of dismantling Article 9, in which Japan renounces war outside of self-defense, has received the bulk of press attention ever since the Abe Cabinet reinterpreted the Constitution to allow for “collective self-defense” of international allies in July 2014; this act set off a series of nationwide demonstrations, culminating in the Students Emergency Alliance for Liberal Democracy (SEALDS) all-night protests in front of the Diet as the Security Laws were passed in September 2015. While the LDP has not clarified which constitutional revisions they will seek, its intentions extend well beyond Article 9: As Lawrence Repeta has noted, the LDP’s blueprint for constitutional revision, last published in April 2012, would change not only most of the articles but also the overriding tone of the 1947 Constitution.

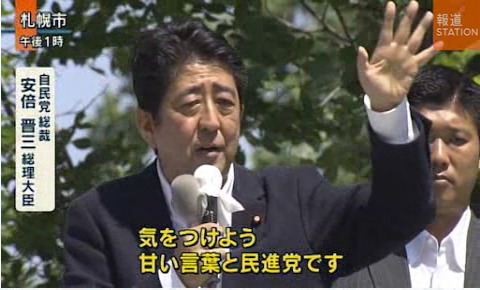

Television news coverage of the campaign

Following the passionate and well-attended protests against the Security Law in 2015, one might have expected greater levels of voter interest in the constitutional issue. However, Abe downplayed constitutional revision during the campaign, framing the election instead as a referendum on Abenomics, his program to revive the Japanese economy. Following Abe through a series of campaign speeches on the street (gaitō enzetsu), the Asahi News Network pointedly noted that the prime minister “did not mention constitutional revision even once,” instead criticizing the “irresponsibility” of the opposition parties and saying that he was only half-way through with Abenomics.

|

Abe Shinzō on Asahi TV, 8 July 2016 |

Nor did the media help to stir up the debate. One reason for this is that the campaign period is legally limited to seventeen days, which does not afford much time to generate public and media interest in a particular issue or candidate. Regardless, I personally saw no substantive discussion or debate on the issue of constitutional revision on television, on which most Japanese rely for news, during this period. Instead, long news spots were dedicated to portraits of the Japanese victims of the terrorist attack in Bangladesh and violence in the United States.

A search on Factiva on Japanese television for the campaign period (June 23 to July 9) yielded 364 spots that mentioned the Upper House election; of these, only 41 mentioned “Constitution” or “constitutional revision.” Moreover, most of these spots simply emphasized the importance of the two-thirds majority without discussing the significance of a change in the Constitution; only a handful mentioned which aspects of the Constitution were likely to be changed. Furthermore, some of these spots were placed at the end of a 30-minute program, where they were less likely to be heard or remembered. Several opposition members questioned the conspicuous absence of any LDP discussion on constitutional revision, particularly the lack of clarification on which of the many redrafted articles they planned to revise (e.g., Fuji TV, 3 July, 7:52am; NTV, 25 June, 4:20am). And while the opposition parties did emphasize constitutional revision when they campaigned in the streets, voters were unlikely to hear concerted explanations on television. On an NHK spot shortly after the election, Hōsei University professor Yamaguchi Jirō labeled this lack of discussion “deceitful to the people” and “counter to democratic principles.”

Not surprisingly given this lack of media attention, voters prioritized other issues. When television network TBS asked 1,200 adults what their top three issues for the election were, they found constitutional revision to be well down the list:

|

Issue |

Percentage of voters citing |

|

Social security, e.g. pensions and medical care |

23% |

|

Economy and employment |

18% |

|

Aging society and child-rearing measures |

15% |

|

National security |

8% |

|

Energy policy, such as nuclear power |

7% |

|

Constitutional revision |

7% |

|

Money in politics |

6% |

|

Education reform |

5% |

|

Foreign policy |

4% |

|

Okinawa US military base issue |

4% |

Hence, despite the far-reaching implications of a supermajority for constitutional revision, voter turnout for the 2016 election was low, at 54.7%—the fourth-lowest for an Upper House election, according to Kyodo News. This election was the first in which 18- and 19-year-olds were allowed to vote, but their turnout was even lower, at 45.5%; they also voted for the LDP and Komeitō in greater proportions than did the elderly population.

An NHK election exit survey showed that voters were equally divided between those who believed that constitutional revision was necessary (33%) and those who did not (32%); the percentage of anti-revisionists had actually risen by seven points since the 2013 Upper House election, while the pro-revisionists had fallen by six. But a significant percentage of voters for the pro-revisionist parties (15-21%) said they were against revision, while 11-17% of voters for the anti-revisionist parties were for revision; this mismatch lead NHK to conclude that voters placed little importance on the issue of constitutional revision. More revealing was the fact that the percentage of voters who said “no opinion” on constitutional revision was higher than either the pro- or anti-revisionists, at 36% for all voters and 52% for 18-to-19-year-old voters. Such numbers suggest that voters had little awareness of the issues behind constitutional revision.

Following the election, the Abe government said it would begin Diet discussions on constitutional revisions this fall, beginning with what it believes to be less contentious issues.

The difficulties of critical information

|

This pattern of delayed or sparse information disclosure follows a pattern that came into stark relief during the 3.11 crisis, particularly with respect to the Fukushima nuclear disaster. As it is, the press-club system, which provides preferential access to key government agencies and people for selected journalists, has been criticized for encouraging information distribution over investigative reporting. As explained in the book, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised: Protest Music After Fukushima, the Fukushima nuclear accident exposed the underreporting of maintenance irregularities, accidents, and collusion in the nuclear industry. Following the accident, crucial information was reported well after the fact, including the path of radiation flows (which the government system SPEEDI had estimated), the possibility of a meltdown, and radiation leaks into the ocean. Outrage over limited information disclosure was among several factors feeding into antinuclear protests, which themselves went underreported.

These concerns were heightened further by the sudden passage of the Secrecy Law in December 2013. This law punishes the unauthorized disclosure of a state secret by ten years’ imprisonment for the person entrusted with the secret (e.g., a bureaucrat) and five years’ imprisonment for the person receiving it (e.g., a journalist, academic, citizen’s group, or legislator). However, as one does not know what is classified as a state secret, the law could discourage investigative journalism or whistleblowing.

Recent events have further alarmed media watchers. In February, when Internal Affairs and Communications Minister Takaichi Sanae said that the government could suspend broadcasters that are not “politically neutral”, Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga defended her. Over the following months, several prominent television news commentators who had been critical of government policies or asked hard questions–Kuniya Hiroko of NHK’s “Close Up Gendai,” Kishii Shigetada of TBS’s “News 23,” Furutachi Ichirō of TV Asahi’s “Hōdō Station,” and Koga Shigeaki of “Hōdō Station”—left their posts. Reporters Without Borders dropped Japan’s ranking in press freedom to 72 out of 180 countries in 2016, down from 11 in 2010.

|

Takaichi Sanae on TBS, 8 February 2016 |

Several of the constitutional revisions outlined in the LDP’s 2012 blueprint have implications for press autonomy and free speech. As Lawrence Repeta has noted, the LDP’s proposed Article 19-2 reads, “No person shall improperly acquire, possess or use information concerning individuals.”1 Not only is “information concerning individuals” an all-encompassing descriptor that could include names and photographs, but the prohibition is also against “improper” use, as opposed to “illegal” use. Citizens would be taking a risk as to what a government authority might interpret as “improper.” Bloggers have raised concerns that the article could make it more difficult for journalists and writers to conduct interviews, or for activists to collect signatures for petitions, among other issues. Coupled with the Secrecy Law, the article could further dampen investigative journalism and writing.

Article 12, which guarantees individual freedoms and rights, would be redrafted to say that “the people will be aware that duties and obligations accompany freedoms and rights and shall never violate the public interest and public order.” “Freedoms and rights” would be subordinate to “public interest and public order,” which according to the LDP’s Q&A pamphlet is the maintenance of “social order” and a “quiet life.” As public protests involve noise and occupation of public space, they could be interpreted as a disturbance of public order.

To Article 21, which guarantees freedom of speech, press, assembly, and association, the LDP would add, “Notwithstanding, engaging in activities with the purpose of damaging the public interest or public order, or associating with others for such purposes, shall not be accepted.” The prohibition is not against actions that actually disturb the public order, but those that simply aim to do so; the authorities would be interpreting that aim. Repeta notes that the revision has the potential to diminish protections for the right of free speech as well as the right of association.

Following their electoral victory, the LDP has suggested that it may first discuss “less controversial” revisions of the Constitution, such as Article 98, which would grant the prime minister the power to declare a national emergency. But national emergencies in the proposed article include not only armed attacks and natural catastrophes, but also “disturbances of the social order due to internal strife, etc.,” making for a broad and vague set of circumstances. Under such emergencies, Repeta notes, the Cabinet would be able to enact orders with the same effect as laws (Article 99), without the scrutiny of a Diet debate. He points out that speaking out against government policy during a national emergency would likely conflict with the maintenance of “public interest and public order” and be prone to harsh punishment.

Rebukes and victories

The ruling government suffered a few rebukes at the ballot box. Two cabinet ministers—Shimajiri Aiko, State Minister for Okinawa and Northern Territories Affairs, and Iwaki Mitsuhide, Minister of Justice–were defeated respectively in Okinawa and Fukushima, two prefectures that have borne the brunt of particularly heavy burdens. Immediately after the election, construction on the long-delayed helipad in Okinawa was resumed, prompting a new round of protests from citizens and the governor.

In Kagoshima prefecture, former Asahi TV commentator Mitazono Satoshi was voted in as governor, ousting the LDP incumbent who had approved the restarting of two nuclear reactors at the Sendai Nuclear Power Plant in 2015. Mitazono plans to call on Kyushu Electric Power to suspend the two reactors pending additional safety checks, following recent earthquakes and seismic activity in Kyushu.

On July 31, former defense minister Koike Yuriko was elected as Tokyo governor in a landslide victory that was a slap in the face for the LDP, which did not nominate her as its candidate, but a victory for conservatives nonetheless. Koike’s status as one of Japan’s few successful female politicians, combined with the LDP’s endorsement of another candidate and Ishihara Shintarō’s heckling her as an “old woman with too much makeup,” provided the governor with an attractive narrative for herself as a woman who is undaunted by bullying and untainted by corruption, allowing her to become the first female governor of Tokyo. Meanwhile, the opposition candidate, Torigoe Shuntarō, was damaged by allegations of a sex scandal from 2002. These media sideshows, again, overshadowed policy discussions.

While Koike’s policy statement pledged to promote “diversity” in education, she did little to clarify what she meant by “education reform.” This has concerned liberal parents given Koike’s strong reputation as a conservative. An active member of Nippon Kaigi, she has advocated making “moral education part of the curriculum with the goal of clarifying standards for unacceptable conduct and duties and responsibilities,” which is reminiscent of pre-1945 school curricula. The conservative Japan Society for History Textbook Reform endorsed Koike in the election, as the only major candidate to support their activities. Koike may have more say in shaping Tokyo’s curricula than her predecessors, thanks to a law passed in 2014 giving local governments more power in regional education policy. She has also voiced opposition to having free Korean schools for the zainichi community and is believed to be opposed to foreign immigration and open to nuclear weapons.

Coda

On the weekend of the election, SEALDs hosted a series of concerts titled, “Don’t Trash Your Vote,” as if to bring their supporters together for a last party before dissolving the organization, which its leader Okuda Aki later announced for August 15. Well-known musicians like the Boredoms and Gotch (Gotō Masafumi of Asian Kung-Fu Generation) helped to attract sell-out crowds. SEALDs rapper UCD performed several tracks from his recent EP, his rapping skills audibly honed through two years of constantly rapping call-and-response patterns in protests. The last evening, on election night, featured an unannounced performance of the Ese Timers, with Gotō, Hosomi Takashi of Hiatus, and Toshi-Low of Brahman performing political covers in a homage to the Timers. Looking disappointed with the early results, Gotō remarked, “It’s written in the Constitution that the people must protect it with tireless efforts, which we must maintain for all of our lives.” Even though the results of the election did not go as they wanted, they wished the audience a bright tomorrow.

|

From a SEALDs concert in Shimokitazawa, 9 July 2016 |

Notes