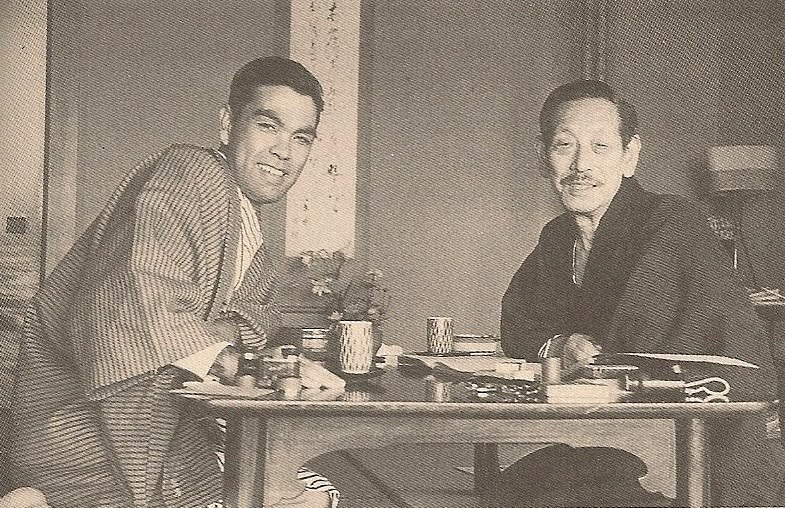

Kayano Shigeru (1926-2006) was an inheritor and preserver of Ainu culture. He was a collector of Ainu folk utensils, teacher of the prominent Japanese linguist Kindaichi Kyōsuke, and recorder and transcriber of epics, songs, and tales from the last of the bards. In addition, Kayano was the compiler of an authoritative Ainu-Japanese dictionary, a chanter of old epics, and the founder of a museum of Ainu material culture as well as of an Ainu language school and a radio station. He was the first (and so far the only) National Diet member to address the assembly in Ainu. He was also a fierce fighter against the construction of a dam in his village that meant destruction of a sacred ritual site as well as of nature. Finally, Kayano was an inspiration behind today’s appreciation of Ainu culture, in which young people, Ainu, and non-Ainu of various nationalities, join to celebrate and explore aboriginal cultures and their contemporary development. This movement includes youthful attempts to create new forms that combine traditional Ainu oral performances with contemporary music and dance. Ainu Rebels, a creative song and dance troupe that formed in 2006, for example, is constituted mostly of Ainu youth but also includes Japanese and foreigners. The group draws on Ainu oral tradition adapted to hip hop and other forms and also engages in artistic activities that combine traditional Ainu art with contemporary artistic elements.

|

Ainu Rebels 2009 performance with German subtitles |

The three major genres of Ainu oral tradition were kamuy yukar (songs of gods and demigods), yukar (songs of heroes), and uepeker (prose, or poetic prose, tales). The Ainu linguist Chiri Mashiho (1909-61, brother to Chiri Yukie whose work is included in this issue) located the origin of Ainu oral arts in the earliest kamuy yukar, in which a shamanic performer imitated the voices and behavior of the gods. In Ainu culture, everything had a divine spirit: owl, bear, fox, salmon, rabbit, insect, tree, rock, fire, water, wind, and so forth. Some spirits were not so esteemed or were even regarded as wicked, while others were revered as particularly divine. This gestured mimicry apparently developed into kamuy yukar, or enacting of songs sung by gods, in which a human chanter impersonates a deity. Kamuy yukar later included songs of Okikurmi-kamuy (also called Kotan-kar-kamuy) about Okikurmi, a half-god, half-human hero who descended from the land of gods to the land of the Ainu to teach humans how to make fire, hunt, and cultivate the kotan (hamlets) where they lived.

The following story by Kayano, published in 1975 (reprinted in 1999) as a children’s book with Saitō Hiroyuki’s illustrations, is an adaptation-translation from an old kamuy yukar dramatizing a contest of strength between the goddess of the wind and the demi-god Okikurmi.

|

Book cover to Kayano Shigeru, The Goddess of the Wind and Okikurmi |

I am Pikatakamuy,

Goddess of the Wind from the land of the gods.

I have the power to fly through the sky

and to raise winds at will,

whether

a gentle waft

a strong gust

or a stormy blast.

In the land of the gods

and in the land of the humans,

women need be good at embroidery.

I lived at my house in the land of the gods

and passed my days

always embroidering.

One day,

I stopped my hand that held a needle

and chanced to look

across the land of the humans.

A village caught my eye.

It was a big village of the Ainu.

How cheerful the village looked!

All the villagers

were busily working.

Children and little dogs ran about joyfully.

My old habit began again:

“All right, I’ll dance the dance of the winds

and scare the humans—”

so I thought.

Once I felt like playing tricks

there was no restraining myself.

Right away, I put on

layers of very beautiful

wind-stirring robes,

storm-hurling gowns

that I had embroidered.

Then, with a swoop

I flew up to the sky.

I flew and flew across the sky—

And on landing on a lofty mountain,

I chanted,

“Blow wind, blow wind—”

and began to dance my dance,

my wind-stirring dance,

my storm-hurling dance.

Then, as usual,

from the tips of my fingers,

from the sleeves of my robe,

fierce winds began to blow.

They blew from the mountains out to sea,

raising fearful large waves.

The large waves,

like waterfalls,

began pounding

upon the village of the Ainu.

The raging winds

made me so happy.

Day and night with no rest,

for six days straight,

I danced.

When I finished dancing

and looked at the village of the Ainu,

it was clean and bare.

Not one thing was left.

Yet I found—

One house was still there. All alone.

It was the house where a young man lived.

Upset and upset,

at once, I danced more fiercely than before.

When I finished dancing,

I looked carefully, and there it was,

the house, not yet blown away.

Upset and upset, I thought of trying one more time,

but too tired to dance again, with nothing to do

I went home to the land of the gods.

When I came home,

again I passed my days

embroidering.

After days had passed, one day

I remembered the events in that village

and looked its way. To my surprise,

the village, which I thought I had blown away,

was just as it had been before.

Having rebuilt the houses,

All the villagers lived cheerfully.

Angered and angered to see this,

putting on at once my wind-stirring robes

and storm-hurling gowns,

I flew to the top of the mountain

and danced powerfully,

the wind-stirring dance, the storm-hurling dance.

From the tips of my fingers,

from the sleeves of my robes,

fierce winds began to blow.

Sand storms swirled around the Ainu village.

Creating such turmoil,

it was as if the sea was turning upside down.

Day and night for six days,

as I sent the winds,

the gods of the trees began wailing

so as not to be blown down.

Big trees broke with snaps,

while those that did not break

flew away, pulled up by the roots.

While dancing the wind-stirring dance,

the storm-hurling dance,

I glanced at the village of the Ainu.

The village had blown away, leaving

a bleak, empty wasteland.

Yet, believe it or not,

all by itself, the young man’s house

still stood there

as it had before the storm.

Appalled by this,

I gave up trying to blow the house away,

went home to the land of the gods

and passed my days embroidering.

Soon afterwards,

Suddenly, at my door

a young Ainu appeared.

How daring of him to come to my door.

Before I, a goddess, had realized it—

I was angered by the terrible Ainu.

But he smiled sweetly and said,

“Pikatakamuy, goddess of the wind,

thank you for showing us your delightful dance.

As a token of gratitude, let me show you

the dance of the Ainu.”

The moment he said this—

The young man came into my house,

and started to dance his dance.

Then from the tips of his fingers

from the sleeves of his robe, began blowing

strong, strong, fierce winds.

Things fell from the shelf.

Ashes and fire rose from the fireplace.

The house shook. The ceiling tore apart.

Moments later a mere framework

was all that was left of the house.

“Pikatakamuy, goddess of the wind,

The dance of the Ainu is not done yet,

I will show you another.”

Taking from his pocket

a fan, he danced.

On the fan was a drawing

of cold winter clouds.

And as he fanned,

cold, cold winds blew at me.

When he fanned harder,

snow and hail danced around,

grains of ice pelting against me.

In the blink of an eye, my robes were torn.

My entire body was

covered with bruises.

My body was cold as ice.

I thought I was freezing to death.

Then the young man said,

“Pikatakamuy, goddess of the wind,

the dance of the Ainu

is not done yet.”

With this he flipped his fan.

Now there was a drawing

of a burning red sun.

This time, each time he fanned

there was dazzling light

and a hot, hot wind.

It was hot, so hot, my eyes went blind.

My skin scorched and charred.

It was so painful

that I could think of nothing.

Falling like a rag,

I lost my senses.

After a while when I came to,

the young man approached me and said,

“Pikatakamuy, why did you

destroy the village of the Ainu?

Because of you so many humans

have lost their lives.”

“I thought, Pikatakamuy,

of killing you as I should have.

But you are the goddess of the wind in the land of the gods.

So I only punished you while keeping you alive.

If you make such strong winds one more time,

know that I won’t forgive you then.”

This said, the young man fanned me

with his fan.

Strangely, each time he fanned,

bruise after bruise on my skin

was gone.

As the young man fanned me with his fan,

my robes that were like tattered cloth flipped and flapped

into the beautiful robes they were before.

No, not only that—as he fanned around him,

my shattered house pulled and heaved

into the fine house that it was before.

“Who are you?

Please let me know your real name.”

When I asked,

“I am Okikurmi,”

the young man answered briskly.

“What? So you are Okikurmi!”

I was stunned to learn his name.

No wonder he was so strong.

Okikurmi is none other

than the strong, strong, wise youth, who went

from the land of the gods to the land of the Ainu.

Ever since then,

I have sent no strong winds

toward the Saru River

near where Okikurmi lives;

I only send

gentle winds,

refreshing winds,

healing winds.

In these words,

Pikatakamuy, the goddess of the wind

told us the story

of Okikurmi and the village of the Ainu.

About This Picture Book

This is a retelling in modern Japanese from a kamuy yukar in literary Ainu, further adapted into a style fit for an illustrated storybook. Pikatakamuy, the spirit of the wind, is a wind that blows down from the mountains, or yamase (cold mountain wind) in Japanese, and it is regarded as a wenkamui (evil spirit). The general word for “wind” in Ainu is rera, which includes both good and bad winds. This explains why the wind in this story is called Pikatakamuy. Okikurmi, who punishes this evil god, is the guardian god of the Ainu and is also called Ainurakkur (humanlike god, with “Ainu” meaning “human”), who teaches humans the skills needed for their daily lives. He lives in human villages and encourages the gods to protect the Ainu, and occasionally, as in this story, he punishes gods who play wicked tricks. Through Okikurmi, Ainu have expressed their ideal human image.

The Ainu have a unique view of the gods (kamui). The gods are not the absolute; they are divine only to the extent that they are beneficial to humans. For example, if a child drowns in the river, the Ainu would sharply reprimand the god of the river, saying, “This came about because you were not watchful. From now on, be sure to protect Ainu.” Of course, the Ainu not only expected protection but also rewarded the gods with prayers and constant offerings of inau. Inau is a ceremonial whittled twig or pole, usually of willow, with the shavings still attached and decoratively curled. Inau is equivalent to the Japanese gohei, a sacred staff to which strips of cut paper are affixed.

This translation is based on Ainu no min’wa: kaze no kami to Okikurumi (The Goddess of the Wind and Okikurmi), narrated by Kayano Shigeru and illustrated by Saitō Hiroyuki (Tokyo: Komine Shoten, 1975). Reprinted in 1999. First published in The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 9, issue 43, no. 2 (October 24, 2011). Kyoko chose to use the Ainu name Okikurmi instead of the Romanized Japanese Okikurumi.

Notes

Simon Cotterill covers this movement, including Ainu Rebels. See “Documenting Urban Indigeneity: TOKYO Ainu and the 2011 Survey on the Living Conditions of Ainu Outside Hokkaido,”Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 9, issue 45, no. 2 (November 7, 2011), available at http://japanfocus.org/-Simon-Cotterill/3642.