On April 13, 2016, about one hundred elderly people assembled in front of a stone memorial plaque in a park in Tokyo’s Toshima ward. Although their number has gradually diminished, they have been meeting on this day every year for more than two decades. Their purpose is to remember the victims of a massive firebombing raid that reduced three quarters of Toshima to ashes on the night of April 13-14, 1945. Most of them are now in their late eighties or early nineties, but they have vowed to continue to hold this meeting, the Nezuyama Small Memorial Service, for as long as they are able.

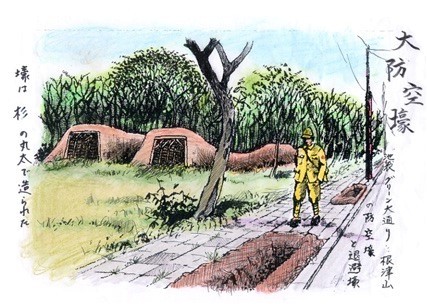

Nezuyama was the local name for a thickly wooded area to the east of Ikebukuro Station. During the war, four large public air raid shelters were built there. On the night of the air raid, hundreds of people fled from the fires to the shelters. The heat of the conflagration around Nezuyama was so intense that whirlwinds raged through the woods. The following morning, the bodies of 531 people who perished in the fires in the surrounding districts were temporarily buried in a field at the southwest corner of the woods. All that remains of Nezuyama is that space, now Minami-Ikebukuro Park, where they hold the memorial service every year.

|

Memorial plaque for the victims of the April 13-14 air raid in Minami-Ikebukuro Park. The map at the top left shows the burned area of Toshima ward in red. (Photograph by the author) |

After the war, Ikebukuro was developed into one of Tokyo’s biggest commercial and entertainment districts. On August 13, 1988, an article in Asahi Shimbun mentioned that a large number of human bones had been found under Minami-Ikebukuro Park during construction of the Yurakucho subway line. According to one of the workers, because they were behind schedule, they simply purified the bones with salt and put them back in the ground. This shocking revelation was the trigger for a grassroots movement that led to the inauguration of the Nezuyama Small Memorial Service. The first service was held on April 13, 1995. In August of the same year, Toshima ward erected the memorial plaque for the victims.

Apart from the survivors, very few people remember the air raid of April 13-14, 1945. It is hardly mentioned in books on the bombing of Japan. The seven-volume official history of the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) in World War II devotes just two sentences to it1, while the most detailed account of the firebombing of Tokyo gives it just five lines.2 However, in terms of the number of bombers deployed and tons of bombs dropped, this mission, codenamed Perdition #1,3 was the largest incendiary attack on Tokyo at that point in the war. The bare statistics are as follows: From 10.57 p.m. to 2.36 a.m. on the night of April 13-14, 327 B-29s dropped a total of 2,120 tons of incendiary and high-explosive bombs on Tokyo, burning out a total area of 11.4 square miles, destroying 170,546 buildings, leaving 2,459 people dead and 640,932 homeless.

In this article I examine the background, aims, execution, results, and memories of Perdition, particularly in the context of the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 10. I have used mainly primary sources, including US documents such as Tactical Mission Report No. 67, damage assessment reports and the US Strategic Bombing Survey, and Japanese sources such as newspaper articles, diaries, and eyewitness testimonies left by 105 victims on the ground. Of these survivors, 65 lived in Toshima ward, which suffered the greatest damage.4

The bombing of Tokyo during the Pacific War did not begin in earnest until November 24, 1944, when 111 B-29s raided the Nakajima aircraft factory in Musashino. The fall of Saipan the previous summer had at last made it possible for the Superfortress heavy bombers to fly the 1,300 miles to Tokyo from the Mariana Islands. Although the initial missions of the Twentieth Air Force’s XXI Bomber Command were almost entirely daylight precision attacks on military targets using high-explosive bombs, the USAAF strategists were already refining plans for incendiary raids on urban areas. They planned a major firebombing campaign for the following spring when the weather, particularly wind conditions, would be ideal for inflicting the maximum fire damage. By that time, senior airmen anticipated that sufficient numbers of B-29s would be available to conduct a series of massive firebombing attacks on Tokyo and five other Japanese cities by all three Wings of the XXI Bomber Command from the Mariana bases of Saipan, Tinian and Guam. In late November 1944, in response to a suggestion that the USAAF commemorate the anniversary of Pearl Harbor by bombing the Imperial Palace, Commanding General Hap Arnold replied, “Not at this time. Our position – bombing factories, docks, etc. – is sound. Later destroy the whole city.”5

The results of the first three experimental incendiary raids were not very promising.6 On February 25, 1945, however, 172 B-29s unloaded over 400 tons of incendiary bombs on the Kanda and Shitaya wards of Tokyo from an altitude of 25,000 feet. This time the results encouraged Air Force planners. In spite of the deep snow on the ground, the fires burned out one square mile of the city below, destroying 20,681 buildings. This experimental firebombing raid was the prelude to an inferno that would wipe out half of Tokyo. It gave the new Commander of the XXI Bomber Command, General Curtis LeMay, an idea: if such damage could be inflicted in daylight by radar from high altitude, a low-altitude night attack would be even more effective. This would eliminate the weather problem, improve bombing accuracy, and increase bomb loads by saving fuel. The outcome exceeded LeMay’s wildest expectations. In the early hours of March 10, 279 B-29s dropped 1,665 tons of incendiaries over the Shitamachi district of Tokyo, bombing individually at altitudes from 5,000 to 8,000 feet. Fanned by the gale-force winds blowing that night, the resulting firestorms destroyed 15.8 square miles of the capital, leaving an estimated 100,000 people dead and one million homeless. Now known as the Great Tokyo Air Raid, it remains the most devastating air raid in the history of modern warfare.

Tokyo was just the beginning. In a series of night incendiary raids, the XXI Bomber Command firebombed Nagoya on March 11, Osaka on March 13, Kobe on March 16, and Nagoya again on March 19. During what came to be known as the “March fire blitz,” it laid waste to 32 square miles of four of Japan’s largest cities. This ten-day firebombing campaign, particularly the Great Tokyo Air Raid, transformed the status of the USAAF overnight. Intoxicated by these spectacular successes, LeMay and other leading air force officers were now convinced that firebombing alone could end the war. After studying reports of the March fire blitz, the Joint Target Group designated 33 “urban industrial concentrations” to be included in a comprehensive plan of attack. On April 3, General Lauris Norstad wrote to LeMay, “If we are successful in destroying these areas in a reasonable time, we can only guess what effect this will have on the Japanese. Certainly their war-making ability will have been seriously curtailed. Possibly they may lose their taste for more war. I am convinced that the XXI Bomber Command, more than any other service or weapon, is in a position to do something decisive.”7

LeMay was eager to press on with the firebombing campaign immediately after the March attacks, but met with an unexpected obstacle: the XXI Bomber Command had run out of incendiary bombs. According to LeMay, the navy had failed to take seriously his warning that stockpiles were running low, and now informed him that the number of incendiaries required could not be delivered until mid-April. He later said in his memoirs, “We couldn’t mount another incendiary attack for almost four weeks. Folks hadn’t believed us and folks hadn’t supplied us … we flew some missions in between, but we couldn’t do another hour of incendiary work.”8 The “missions in between” included the bombing of Kyushu airfields in support of the planned Okinawa invasion and the aerial mining of the Shimonoseki Straits in support of the blockade of Japan. The latter mission, Operation Starvation, is considered to have been highly effective, but LeMay viewed it as a distraction from what he saw as his command’s most vital task: the incineration of the rest of Tokyo and, if necessary, every other city in Japan.

On April 13, 1945, the USAAF was finally ready to launch Perdition. According to the Tactical Mission Report, the target of the air raid was the “Tokyo arsenal complex” located in the northwest of the capital. It stated: “This area is probably the greatest arsenal complex in the Japanese Empire. It contains over a dozen large and important arsenal targets interspersed with transportation, industrial, and scientific research installations. It also contains many industrial workers’ quarters.”9 The complex consisted of the Oji and Akabane army arsenals in Oji ward (now Kita ward) and the related factories and explosives warehouses. However, it is important to note that not only these factories but also the homes of “industrial workers” living around them were targets of the mission. Perdition was not a precision raid on specific targets but an attack on a whole area designated by the Joint Target Group as Tokyo Urban Industrial Concentration 3600 (UIC 3600). This was a 10.6 square-mile area consisting of Oji ward, Takinogawa ward, eastern Itabashi ward, northern Toshima ward and western Arakawa ward, bordered by the Arakawa River in the north and the Yamanote railway line in the south. Although UIC 3600 contained the “Tokyo arsenal complex,” it was predominantly residential, so it was sure to contain many of the “industrial workers’ quarters” designated as a target. As USAAF General Ira Eaker remarked after the war, “It made a lot of sense to kill skilled workers by burning whole areas.”10

Three aiming points within UIC 3600 were set, all of them in Oji ward in the upper two-thirds of the target area, where the greatest industrial concentration was located. These aiming points and the Wings assigned to bomb them were:

- Army Arsenal and Military Gunpowder Works (Target 205): 73rd Wing

- Army Central Clothing Depot (Target 202): 313th Wing

- Japan Artificial Fertilizer Factory (Target 204): 314th Wing

The incendiary weapons to be used were the same as those that had incinerated the Shitamachi district of eastern Tokyo on March 10: 500-pound incendiary clusters (each containing 38 M-69 napalm bombs) and 100-pound M-47 incendiary bombs. However, the planners were aware that they no longer had the advantage of surprise. Realizing that Tokyo would be much better prepared to meet a large-scale incendiary attack, they added 500-pound general-purpose bombs to the mix. One of these high-explosive bombs would be dropped first by each aircraft to create terror and confusion on the ground, paralyzing firefighting efforts. Carried by the first twenty planes across the target from each Wing, they were set to burst in the air. As its codename suggests, the planners had high hopes for Perdition.

The government and citizens of Tokyo had not been idle during their month of grace following the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 10. Although no details of the devastation caused by the air raid were provided in newspapers or radio broadcasts, rumors about the horrific ordeal of the victims spread quickly as hundreds of thousands of refugees streamed out of the Shitamachi district into all parts of Tokyo and beyond. The rumors sent waves of shock and fear throughout the capital, and many people decided to get out while the going was good. From March 13 to April 4, a total of 819,841 people evacuated to the country from Ueno, Shinagawa and Shinjuku stations.11 From the beginning of April, twenty-nine special trains were reserved solely for the “mass dispersion” of aged persons, children and expectant mothers out of Tokyo.12 Initially paralyzed by the sheer extent of the damage, five times greater than anything they had planned for in civil defense, the Tokyo authorities hastily implemented a drastic program of building demolition to create firebreaks. On March 19, the Metropolitan Assembly passed a huge supplementary budget of almost two billion yen for this demolition program, through which 100 firebreaks were to be established in the capital within a month. Residents were given just five to fourteen days to vacate the houses earmarked for demolition. Needless to say, this caused immense hardship to citizens already under great duress. Hidaka Momoko, who was eleven years old at the time, recalled: “We had been ordered to evacuate by March 31. I stayed in Tokyo to take a school entrance examination and cried when I saw our house being destroyed by a tank.”13 Tanks were only used when necessary; in most cases neighborhood groups tied ropes around the houses and pulled them down by manpower alone. Through this program, 143,120 buildings throughout Tokyo were torn down, displacing at least half a million people.14

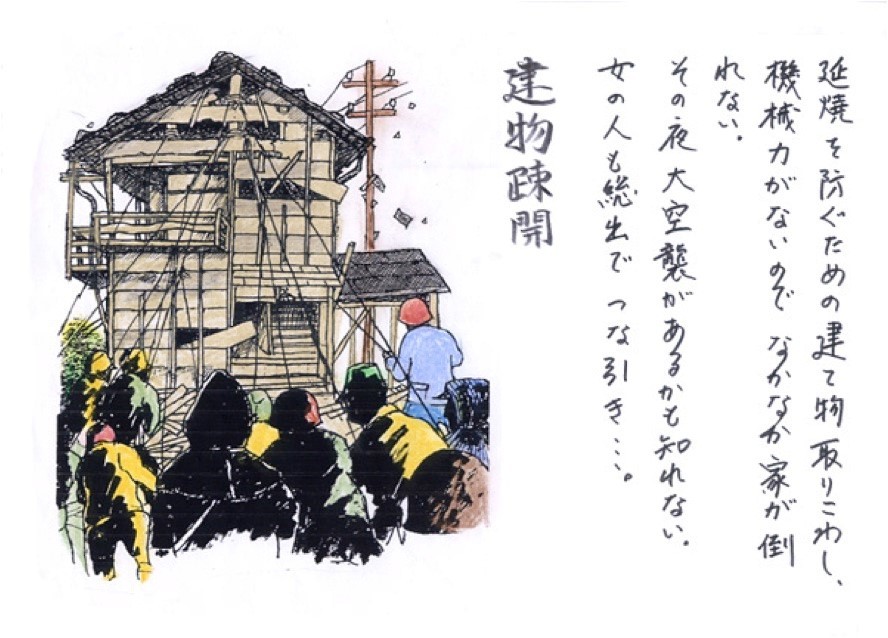

In Ikebukuro, the work was not completed on time. According to Kazama Hiroo, a 33 year-old company employee, “April 13 was the deadline for the demolition of the houses around Ikebukuro Station left empty after the forced evacuations up to the end of March, but now that all the young men were either fighting overseas or working in factories, the demolition work was behind schedule. When the deadline came, most of the empty houses in the surrounding neighborhoods were still there.”15

|

A house being pulled down in Ikebukuro “We demolished buildings to prevent the spread of fires, but without the help of machinery they didn’t come down easily. A big air raid might come that night, so even the women helped pull the ropes.” Painting by Yajima Katsuaki (courtesy of the artist) |

Friday, April 13 was a fine day in Tokyo. After the coldest winter in nearly 40 years, the weather was finally getting warmer and the cherry blossoms were in full bloom. The writer Uchida Hyakken, who nearly lost his house that night, planned to celebrate hanami by drinking six bottles of beer with his friend Furuhi “even under these perilous skies.”16 That afternoon, he heard the news of President Roosevelt’s death on the radio at his company. His colleagues were delighted, but Uchida was more circumspect. “It seems like good fortune, but I cannot help doubting it. Something interesting is bound to happen shortly,” he wrote in his diary.17 Several survivors’ accounts mention this “good news,” some saying that they thought an air raid was unlikely on the day of Roosevelt’s death. Others doubted whether the enemy would attack on such an “unlucky” day as Friday the thirteenth. One of them commented ruefully, “It turned out to be unlucky for us.”18

That night an air-raid alert was issued at 10:44p.m., after the first wave of B-29s had already passed over the Boso Peninsula. According to the Tactical Mission Report, the first bombs were released at 10:57p.m. by the 314th Wing.19 The full air-raid warning sounded at 11:00p.m. Most witnesses state that fires broke out and spread fast at around the time of, or even before, the air-raid warning. Uchida Hyakken, who lived in Kojimachi ward about 700 meters east of the Imperial Palace, recorded in his diary that he saw fires in the east immediately after the air-raid warning sounded. Shortly after that, he heard incendiaries falling in Yotsuya to the west. The nearby Futaba Girls’ High School, a prestigious Catholic school founded in 1909, was soon in flames. Beyond the school, Sophia University was also hit and suffered considerable damage. According to the university records, 74 incendiary and two explosive bombs fell on the campus that night.20 It was located more than five miles south of the southernmost aiming point in the target area, UIC 3600.

|

The ruins of Futaba Girls’ High School on the morning of April 14, 1945 On the gate, a chalk-written message from the headmistress informs students that they can take refuge at nearby Sophia University. Photograph by Hayashi Shigeo (Tohosha) Source: Tokyo Air Raids and War Damage Center |

According to the Metropolitan Police fire department, “the first fires broke out at about 10:50p.m. in Iidabashi in Ushigome ward and Otemachi in Kojimachi ward.”21 Iidabashi and Otemachi were both about four miles south of UIC 3600. Nakaushiro Yoshiro, who was on night defense duty at Koishikawa ward office, later recalled the moment the air raid began: “At around 11:00p.m., our basement headquarters received an air-raid warning from the Air Defense Headquarters and the siren sounded. I ran up to the roof and saw B-29s dropping hundreds of flare bombs over the Korakuen anti-aircraft position, followed by countless incendiary bombs.”22 Korakuen was located 4.3 miles from the southernmost aiming point in the target area.

The all clear sounded at 2:22 a.m., though the last bombs fell at 2:36 a.m., according to the Tactical Mission Report. The raid had lasted 3 hours and 39 minutes, making it the longest of the six maximum-effort incendiary raids on Tokyo during the war.23 It must have been a long and terrifying night for the civilians on the ground, most of whom fled to open spaces such as woods, cemeteries and areas that had been ` burned out by the March 10 air raid. The fires continued to burn throughout the night. What the survivors saw around them after dawn broke is beyond the imagination of anyone who did not witness it. To describe it they invariably used the word yakenohara – a vast burned-out wasteland stretching as far as the eye could see. Nothing was left standing except the shells of a few concrete buildings, stone storehouses, charred tree trunks and telegraph poles. From the woods of Nezuyama people could clearly see, for the first time ever, the green copper roof of Gokokuji Temple in the distance. One survivor described it as “a vision of paradise in the middle of hell.”24 The well-known mystery writer Edogawa Rampo, whose house in Ikebukuro miraculously escaped the fires that night, recalled, “The area burned out by the fires was so large that from my window I could see the mountains in the distance beyond Ikebukuro Station. Those mountains had not been visible before the air raid.”25 In just one night, 170,546 buildings had burned to the ground. 640,932 people had lost their homes and most of their possessions. 2,459 had lost their lives.26

Ironically, it was the unforeseen consequences of the inaccurate bombing on April 13 that had the deepest psychological impact on the Japanese government. Stray incendiaries fell within the Imperial Palace grounds, causing fire damage in 36 places and killing one official of the Imperial Household Ministry.27 The details were never publicly disclosed, but Tokyo Metropolitan police photographer Ishikawa Koyo recorded in his diary that the Imperial Sanctuary, Shintenfu Hall, and Saineikan martial arts hall had all burned down.28 Fires also damaged the Akasaka Detached Palace and the Omiya Palace, the residence of the Empress Dowager. Undoubtedly the most eminent victim of the air raid that night was Marquis Kido Koichi, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and the Emperor’s closest advisor. Kido wrote in his diary: “At around 1:00a.m. our family home in Akasaka was hit by about one hundred incendiaries and burned down. Tsuruko [Kido’s wife] was in the air-raid shelter, but 45 incendiaries also fell there, so she escaped to No. 1 Group Headquarters. The house where we brothers had grown up and raised our children, with all its memories, has been reduced to ashes.”29 Kido fortunately found a vacant property nearby and moved there immediately, but in a sense he was unlucky. That night only 24 houses burned down in Akasaka, which was nearly five miles from the target zone.

The biggest shock of all was the destruction of the Meiji Shrine, the Shinto shrine dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken. Just one “rogue B-29” dropped its 6-ton load of incendiaries on the shrine. A magnificent structure surrounded by thick woods, it must have presented a tempting target, but it was located more than six miles south of UIC 3600. In fact, an earlier USAAF report on strategic objectives in this district had warned that “an attacking force would do well to try to avoid damaging” the shrine.30 Shimano Yoshiki, a 19-year-old student, witnessed the fire from his house nearby: “At first I thought they could not possibly have bombed Meiji Shrine, but then I heard the crackling sound of trees burning behind our house … When I went out to look, I saw sparks rising from the woods around the shrine. It didn’t look like a fire they could put out.”31 The Main Shrine and the Worship Hall burned to the ground. The containers of 1,330 M-69 incendiaries were reportedly found in the ruins of the shrine’s inner precinct.32 Prime Minister Suzuki Kantaro expressed the anger of the Japanese government in the typical rhetoric of the time: “The enemy’s acts of atrocity and disrespect to the Imperial Palace and Meiji Shrine … are hideous crimes beyond description. We, the subjects, are enraged at the American acts. I hereby firmly determine with the rest of the 100,000,000 people of this nation to smash the arrogant enemy, whose acts are unpardonable in the eyes of Heaven and men, and thereby to set the Imperial Mind at ease.”33

Another unintended consequence of Perdition was the burning down of “Building No. 49” at the Institute of Chemical and Physical Research (Riken) where Japanese scientists under the leadership of Nishina Yoshio were working on a top-secret project to develop an atomic bomb. Although they had reached the first stages of enriching uranium, the consensus among historians is that they were still a very long way from developing a usable bomb.34 Riken Institute was located to the south of Komagome Station on the Yamanote Line, just outside the target zone.

Other damage caused by the air raid testifies to the randomness of area bombing. According to one source, about 140 incendiary bombs fell on Ueno Zoo that night.35 The wooden elephant house received several direct hits and burned down. The three Indian elephants that once occupied it were long gone, starved to death in the summer of 1943 as a precaution against the possible escape of “dangerous animals” during air raids.36 Just ten days before the April 13-14 raid, a captured B-29 crew member, Raymond “Hap” Halloran, had been put on display naked in the empty tiger’s cage at the zoo.37 Another victim of Perdition was the Cancer Research Institute and attached hospital in Nishi-Sugamo. Completed in 1934, the Institute was the only specialized cancer research facility in Japan. The nurses managed to guide the patients to safety in a nearby public air-raid shelter, but the building and research data collected over a decade were destroyed in the fire.

Reports of the damage in the newspapers were unusually detailed. In the Japanese media during the war, news of large-scale US air raids always took the form of an Imperial Headquarters Communiqué. The following communiqué was issued on April 14:

4 p.m., April 14

“1. About 170 B-29 bombers principally raided Tokyo Metropolis for about four hours from 11 p.m. on April 13, indiscriminately bombing the city areas with explosive and incendiary bombs.”

“Fires which broke out at parts of the edifices in the Imperial Palace, the Omiya Palace, and the Akasaka Detached Palace, due to the said bombing, were promptly brought under control, but the Main and Worship Halls of the Meiji Shrine were finally burnt down.”

“The majority of the fires, started at various places in the Metropolis, were extinguished by about 6 a.m. on April 14.

“2. Of the counterattacking battle results obtained by our Anti-Air Raid Forces, those that have become known follow:

Shot down: 41 planes

Damaged: 80 planes.”38

Needless to say, this announcement contains inaccuracies and exaggerations. The number of B-29s over Tokyo that night was 327, of which only seven were lost (two of them shot down) and 51 were damaged. However, according to the novelist Takami Jun, the newspapers provided details of air raid damage for the first time ever.39 Even after the devastating March 10 air raid, the only specific damage referred to in the Imperial Headquarters Communiqué was a fire at the Shumeryo, the Imperial Household Ministry bureau responsible for the Emperor’s horses. The fires that killed an estimated 100,000 people were simply referred to as “Others.” However, the April 15 edition of the Nippon Times, for example, mentioned extensive fire damage in Toshima, Itabashi, Oji, and Yotsuya wards and listed the principal buildings burned down: “Tokyo Metropolitan Planning Bureau, the Nishi Kanda, Ikebukuro, Nishiarai and Nippori police stations, the Oji, Takinogawa and Toshima ward offices, the Tokyo Medical College, the Peers’ School, the Women’s Higher Normal School, and the Otsuka, Nippon University and Okubo hospitals.”40

The reporting of the air raid in American newspapers rivals the Imperial Headquarters Communiqué in both inaccuracy and hyperbole. On April 14, an Associated Press bulletin in the Spokane Daily Chronicle trumpeted: “A record force of about 400 Superfortresses, raining incendiaries, turned Tokyo’s arsenal area into a flaming, exploding holocaust today … It was the 15th, and the largest, B-29 attack on the Japanese capital. Superforts were over the five-mile square target area – the most important military objective they have yet hit – for four hours.”41 Apart from the triumphalist language, this report exaggerates the number of attacking planes and more than doubles the size of the target area. On the same day an article in Chicago Tribune with the headline, “Big B-29 Fleet Sets 25 Square Miles of Tokyo Afire” explained the “tinderbox” theory underlying the raid: “Surrounding the arsenals are little home industries, mostly wooden houses. It was believed here that fire or an explosion in one building should result in uncontrollable fires spreading throughout the area.”42 The actual results of Perdition would expose the fallacies of this optimistic theory.

During the war Tokyo Metropolis consisted of 35 wards, which were integrated into 23 special wards in 1947. UIC 3600 was a 10.6 square-mile area covering all or part of five wards – Oji, Takinogawa, Toshima, Itabashi, and Arakawa. A detailed survey of the damage conducted shortly after the air raid by the Tokyo Metropolitan fire department found that buildings had burned down in a total of 26 wards. Areas were burned out as far west as Suginami ward, in Adachi ward to the north of the Arakawa river, and in Katsushika ward to the east of the Shitamachi district. In a pioneering study of the air raid, the historian Aoki Tetsuo calculated that the burned areas outside UIC 3600 accounted for between 49.1 and 53.4 percent of the total damage.43

|

Areas burned-out in the April 13-14 air raid (based on a map in the US Damage Assessment Report, June 4, 1945) Courtesy of Aoki Tetsuo |

As can be seen from the above map, large swathes of the target zone UIC 3600, particularly around the aiming points, remained undamaged after the air raid. Although all three aiming points were located in Oji ward in the top half of UIC 3600, the damage was concentrated mainly in Toshima, Takinogawa and Arakawa wards. There is little indication in US documents that this wildly inaccurate bombing was considered a problem. The Tactical Mission Report, issued on May 22, stated that “bombing was generally carried out as planned.”44 The report tentatively assessed “visible new damage” as being 10.7 square miles (later revised to 11.4 square miles). The damage assessment report of June 4 was somewhat more circumspect. It noted that, of the total building area damaged by the attack, 90.1 percent represented dwellings, 8.6 percent industrial establishments, and 1.5 percent was mixed industrial-residential. In other words, more than nine-tenths of the total area burned out was residential. The report estimated that the fires destroyed 160,000 to 180,000 dwellings, “dehousing” from 575,000 to 625,000 persons, although it provided no indication of how many of them were “industrial workers.” Regarding deaths and injuries, it simply stated, “No estimate of casualties has been made.”45

A further damage assessment report issued on June 7 gave details of the damage to specific targets in the Tokyo arsenal complex. The results were not encouraging. Of the three aiming points, while the Army Central Clothing Depot (Target 202) had been 75 percent destroyed, the damage at the Army Arsenal and Military Gunpowder Works (Target 205) and Japan Artificial Fertilizer (Target 204) was only 10 percent and 5 percent, respectively. The average damage at the other five numbered arsenal targets surveyed was under 30 percent.46 Two months after the end of the war, the Chemical Section of the Twentieth Air Force conducted a survey on the incendiary attacks against Japanese urban industrial areas. To determine the efficacy of Mission No. 67 (Perdition), they visited Tokyo Arsenal No. 1 in Jujo (Target 206). In interviews with Japanese army personnel, they found that only two B-29s had actually bombed the plant and that none of the 500-pound explosive bombs had hit the arsenal installations. Nevertheless, production had fallen by more than 50% after the air raid, partly because about half of the workforce did not return to work. Regarding the area damaged, this was the first US survey to point out, albeit cautiously, that the bombing had been inaccurate: “11.4 square miles was burned over in this attack, but a portion of this damage was in urban areas southeast of the general target area and somewhat short of the selected aiming points.”47 As US documents themselves confirm, this “portion” was much more extensive, accounting for about half of the total area, and the damage “somewhat short” of the aiming points was as far as six miles away.

|

The ruins of Ichigaya in Ushigome ward, April 14 Ichigaya was about four miles south of the target area. Photograph by Ishikawa Koyo. Source: U.S. National Archives |

Even though the mission failed to do substantial damage to its ostensible military-industrial targets and only burned out about half the targeted area, it caused immense destruction. The total area burned, buildings destroyed, and numbers of people made homeless were about two-thirds of those in the Great Tokyo Air Raid. If Perdition had killed an equivalent number of people, it might not have been forgotten by history. However, the death toll of 2,459 was just one fortieth of the estimated 100,000 people who lost their lives in the early hours of March 10. How can this huge difference be explained? Three factors seem to have been particularly important: wind conditions, topography, and preparedness.

Throughout the day on March 9, a strong northwesterly wind was blowing in Tokyo even before the air raid began. According to statistics of the Central Meteorological Observatory, the average wind speed that day was 12.7 meters per second, with a maximum instantaneous speed of 25.7 meters.48 This fierce wind was mentioned by nearly all of the survivors who left accounts of their experiences. Some said that the wind made it hard even to stand up, while others recalled that it blew heavy futons out of their hands. After the fires started, the wind fanned the flames, creating firestorms that caused the fires to merge into conflagrations of unprecedented ferocity. Blizzards of sparks and burning embers settled on people’s clothes and set them on fire. Many instinctively fled downwind because it was so hard to move against the wind, but the flames soon caught up with them. According to one survivor, the firestorms were so powerful that they blew across the whole width of the Sumida River.49

Few survivors of the April 13-14 air raid mention the wind and two explicitly state that there was no wind before the air raid. The fires themselves generated strong gusts of wind and even whirlwinds, but there is no evidence of the massive firestorms that occurred on March 10. In late March 1945, the USSBS made a comparative study of the five maximum-effort night incendiary raids of the “March fire blitz”. Unlike the Tokyo attack, there was little or no surface wind prior to the four raids that immediately followed it. Although an even greater tonnage of incendiaries was dropped in each of these raids than on Tokyo, the areas burned out were much smaller. Regarding the Tokyo raid, the report concluded that, “It is likely that without a helping wind the damaged area may well have been a third less.”50 Although it does not mention the impact of the wind on casualties, the implication is clear enough.

The second factor affecting the difference in death tolls was topography, both natural and man-made. The target zone for the March 10 air raid was located in the Shitamachi district of eastern Tokyo. Compared to the hilly Yamanote district to the west of the Imperial Palace, the Shitamachi district was a flat, low-lying region characterized by its many waterways. In Honjo and Fukagawa wards, the crisscrossing canals joining the Sumida and Arakawa rivers cut through the towns in a grid-like pattern. Although their population had decreased considerably through evacuation by the time of the air raid, these were two of the most densely populated wards in Tokyo. The wooden houses were tightly packed together and the streets were narrow. There were very few open spaces; even the parks, cemeteries and shrines were much less spacious than those of the Yamanote district. As the fires spread with terrifying speed on March 10, thousands of people instinctively made for the waterways. According to Saotome Katsumoto, one of the lucky survivors that night, “Not many of those who jumped into rivers or canals survived. Flames and scorching blasts of air blew over them from both banks. Large numbers perished even before the flames could get to them, dying of asphyxiation as the fires sucked the oxygen out of the air. Others died of shock from the coldness of the water, froze to death, or drowned.”51 The grid-like network of waterways also hindered escape because the bridges soon filled with people, making it impossible to cross quickly. Several thousand people died in the conflagration on top of Kototoi Bridge over the Sumida River, and as many as two thousand perished on Kikukawa Bridge and in the Oyokogawa canal below.52 A week after the air raid, bodies were still being pulled out of the canal.

|

Bodies being removed from the canal below Kikukawa Bridge, March 17, 1945 Photograph by Ishikawa Koyo. Source: U.S. National Archives |

Although some of the areas burned over by the April 13-14 air raid, such as Arakawa ward, were located in the Shitamachi, most were in the elevated Yamanote district, particularly the burned areas south of the target zone. The difference in elevation within UIC 3600 may itself have slowed the spread of the fires. The analysts of the Joint Target Group were well aware of this, pointing out that, “The western half of the area has an elevation approximately 50 feet above the average elevation of the eastern half, which difference reduces the vulnerability of the area as a whole to conflagration.”53 The vast majority of residents escaped quickly to open spaces such as woods, parks, shrines, cemeteries, firebreak zones, and areas burned in the March 10 air raid. In Ikebukuro, Sugamo and Zoshigaya in Toshima ward, most people took refuge in the public air raids shelters and surrounding woods of Nezuyama and in the spacious Zoshigaya Cemetery. The novelist Yoshimura Akira, who lived in Nishi-Nippori, fled with his neighbors to the higher ground of Yanaka Cemetery. He later recalled, “There can’t ever have been so many people in that cemetery. The sky was red and it was so bright that you could clearly see the inscriptions on the gravestones. The cherry trees were in full bloom. Above them I saw the fuselages of the B-29s reflected in the red flames below.”54 Large open spaces such as these were not available to most residents of the Shitamachi district, particularly in Fukagawa and Honjo wards.

|

The public air-raid shelters in Nezuyama, Ikebukuro Painting by Yajima Katsuaki (courtesy of the artist) |

The third important factor behind the difference in death tolls was preparedness. The unprecedented scale and intensity of the March 10 air raid, and the ferocity of the fires it caused, took the residents, firefighters, and government of Tokyo completely by surprise. Since November 24, 1944, Tokyo had been subjected to as many as 36 air raids, but in total they resulted in just 2,525 deaths. The air raids had become part of people’s daily lives. From the summer of 1942, the neighborhood associations conducted regular drills in which chains of residents carrying buckets of water put out imaginary fires. It was assumed that, in the event of an incendiary raid, citizens would engage in this “initial firefighting” until professional firefighters arrived on the scene. The revised Air Defense Law of 1944 actually prohibited residents from escaping in an air raid “when it is deemed necessary for air defense.” The penalty for infringing this law was a fine of up to 8,000 yen or one year’s imprisonment.55

When the air-raid warning sounded at 12:15 a.m. on March 10, the bombing had already begun and the flames were spreading with terrifying speed. Tsukiyama Minoru, a 16 year-old student living in Fukagawa ward, recalled, “In no time at all, the fires were all around us and it became as bright as day. I had experienced many air raids, but I could never have imagined a conflagration like this. None of our firefighting drills and equipment – the brooms, grappling hooks, ladders, hand pumps, and water-soaked straw mats – would be of any use that night.”56 By the time residents realized their deadly peril, it was often too late. Countless people suffocated or baked to death in their air-raid shelters, most of which were no more than makeshift dug-outs under or next to their houses. Those with more time tried to salvage their most important belongings by loading them onto handcarts, but these often caught fire, with fatal consequences. Apart from the rivers and canals, vast numbers of people headed for the elementary schools, most of which were three-story ferroconcrete buildings designated as evacuation sites because they were thought to be safe from fires. 13 of the 17 elementary schools in Fukagawa ward were gutted by fire that night, and thousands of people died inside them. In Nihonbashi ward, the flames found their way into the Meijiza Theater, a five-story reinforced concrete building, and more than a thousand of those who took refuge there suffocated or burned to death.

The survivors of Perdition had learned some valuable lessons from March 10. They learned that it was impossible to extinguish incendiaries with buckets of water and fire brooms; that, rather than trying to put the fires out, they should escape quickly with as few belongings as possible; that their air-raid shelters might be death traps; and that concrete buildings were not fireproof after all. Shinozaki Hiroshi, a landlord in Nishi-Sugamo, recalled, “Knowing the extent of the damage on March 10, I quickly urged my tenants to escape with me so that they didn’t meet the same fates as the victims of that raid.”57 This kind of information did not come from the government or media, but circulated by word of mouth. It was often quite detailed. Shimizu Matakichi, a factory employee in Ikebukuro, recalled, “We heard that the victims of the March 10 air raid even lost their cups and chopsticks. After the air raid started on April 13, I put chinaware, chopsticks and other items into three jars filled with water and buried them underground.”58 Of the 105 survivors who wrote accounts of their experiences, fifteen mentioned that they put their most important possessions into their air-raid shelters before escaping that night. 43 schools, many of them concrete buildings, were destroyed by the fires, but there is no record of anyone dying inside them.

The Tokyo Metropolitan Police fire department, which lost 128 firemen and 96 fire engines on March 10, implemented a new firefighting policy on April 13-14. According to a report by a local fire brigade, “Learning from the March 10 air raid, when both ordinary citizens’ houses and most of the important factories were reduced to ashes, the fire chief gave the strict order to protect the priority facilities.”59 These priority facilities were government buildings and factories important to the war effort, particularly munitions and explosives factories. As a result, firefighters managed to minimize the damage to the most important factories on April 13-14, but essentially left private homes to burn. In effect this gave residents tacit permission to flee, though they did not need much encouragement. As the fire brigade report put it, “in view of the fears resulting from the large number of deaths and injuries to those fighting fires on March 10, residents placed emphasis on quick escape and initial firefighting ended in failure.”60 It seems that citizens complied with this priority firefighting policy even to the extent of sacrificing their own homes. The company history of Nissan Chemical Industries, Ltd. records how one of its factories was saved on the night of April 13-14, 1945: “In a spirit of self-sacrifice, the workers actively took part in firefighting at the factory, paying no heed to the fate of their own houses. Thanks to their efforts, we were able to keep damage to a minimum.”61 The factory in question was Target 204, Japan Artificial Fertilizer, the aiming point assigned to the 314th Wing. As we have seen, only 5% of this target was destroyed in the fires. It seems that this was due not only to inaccurate bombing, but also to heroic firefighting efforts on the ground.

Relative to the area incinerated and the number of people made homeless, the death toll from the April 13-14 air raid may seem very low. However, the figure of 2,459 dead is by no means negligible; it is, for example, more than the 2,403 Americans killed in Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. While most of the victims of Perdition burned or suffocated to death as in the Great Tokyo Air Raid, some died from the blasts of 500-pound explosive bombs, which were not used on March 10. Hironaka Aikun, an 18 year-old student at the time, recalled, “My friend from college died that night from interior bleeding from a bomb blast. His mother was killed instantly and his sister lost a leg.”62 Although people had more time to escape and more open spaces to flee to, many still perished in the fires. Kariya Yoshio, who narrowly escaped from Ikebukuro 1-chome with his wife and three children, described what he saw when they returned to his neighborhood: “Near the Itsutsumata roundabout at the center of the previous night’s inferno, there were burned corpses here and there on the road. Some lay face down, shriveled and with their backs arched like monkeys, some had had their clothes burned off and were naked or half-naked, others were leaning over a water container with their heads in the water. Most of them were women and children.”63 Kobayashi Keiko, a 27-year-old housewife who lived in Zoshigaya, saw the bodies being brought to Nezuyama for temporary burial: “While we were picking up burned rice and canned foods from the ruins, a truck arrived from Otsuka piled high with charred corpses wrapped in straw. They threw them off the truck as if they were bags of coal. I heard that more than four hundred bodies were brought there. Most of them had their hands held up over their chests as if they were trying to protect a child.”64

Although most people chose to flee rather than risk staying in their air-shelters, many still sought safety underground. Twelve survivors’ accounts mention people, even whole families, dying in their air-raid shelters. According to Henmi Toshiko, who lived with her mother in Horinouchi, Toshima ward, “A family of five suffocated to death from the smoke in their air raid shelter. The father, wearing a civil defense guard’s uniform, was found dead at the top of the stairs near the entrance, his hands raised in the air. Inside the shelter were his two children and his wife holding a baby.”65 Yoshida Iwao, who was a 3rd-year high-school student at the time, told a particularly sad story. Four days after the air raid, he went to Nishi-Sugamo to look for a middle-aged couple who had been kind to him. He found them dead together in their air-raid shelter under the ruins of their home. The wife’s hands were still clasped around her national bonds and other valuables. Yoshida commented, “Those valuables must have been helpful to their surviving 10-year old son and elderly parents who had evacuated to the countryside.”66 The photograph below shows the cremation of the couple in the ruins.

|

A cremation in the ruins in Nishi-Sugamo, mid-April 1945 Yoshida Iwao is standing on the left. Next to him are his mother and three relatives of the deceased. Photograph by an unnamed relative of the deceased Source: Tokyo Air Raids and War Damage Center |

Apart from a few private cremations such as this, the bodies of the dead were temporarily buried in mass graves at various sites throughout the damaged areas. Most of the victims from Toshima ward were buried at the current location of Minami-Ikebukuro Park. One of the survivors, Kazama Hiroo, described the scene: “Several long holes about five and a half feet wide and deep were dug at the southwest corner of Nezuyama with the help of prisoners from Sugamo Prison. The bodies of the victims in Toshima ward arrived in trucks, piled up like tuna. Working in pairs, young policemen in white gloves picked up each body by the feet and shoulders and, standing on either side of the hole, dropped them in. The prisoners then covered them with earth.” Among the bodies were those of the director of Ikebukuro Hospital and a dozen or so nurses, who had perished while attempting to carry patients out of the burning building.67

Japanese civilians were not the only victims of Perdition. According to the records of POW Research Network Japan, 60 B-29 crew members died during the raid. Of the 17 survivors, 14 were interned in the Tokyo Military Prison in Shibuya, where they were among the 62 American airmen who burned to death after guards deliberately left them locked in their cells during the Great Yamanote Air Raid of May 25-26.68 Only two of the seven B-29s lost in the raid were shot down. One of them, nicknamed Wheel n’ Deal, from the 497th Bombing Group of the 73rd Wing, fell in Ikebukuro. All eleven of the crew led by Captain Everett P. Abar died in the crash. Several witnesses mention it in their accounts. Hironaka Yoshikuni, an 18-year old student, saw the B-29 turn into a red ball of flames from the window of his house. Later he came upon the wreckage: “That huge plane had been reduced to just a few pieces of wreckage. Next to it I saw the charred bodies of the crew. Policemen and civil defense guards were loading them onto a three wheeled truck.”69 Wheel n’ Deal came down behind Jurinji Temple, where the remains of the crew were temporarily buried. After the war, they were disinterred and returned to the United States.

What became of the 640,000 or so people made homeless on the night of April 13-14? Among the 105 survivors who wrote accounts of their experiences, 77 lost their homes that night, but only 44 recorded where they went after that. Of these, 24 left Tokyo to live with relatives in the country or to seek accommodation in neighboring prefectures; 14 stayed in Tokyo, finding vacant accommodation or moving in with relatives in other districts; and six lived in their air-raid shelters or in makeshift homes built from corrugated metal and other materials they could salvage from the ruins. According to a USSBS survey conducted after the war, out of the 2,861,857 people in Tokyo made homeless by air raids, 1,922,739 – about two-thirds of the total – went to live with friends or relatives in the country.70 This proportion is higher than in the small sample for April 13-14, but it can be assumed that the numbers of people leaving Tokyo increased as it was steadily laid waste by three more massive firebombing raids after Perdition.71

In the days following the air raid, people slept in their air-raid shelters, in parks, or at temporary refugee shelters. Of the 161,611 people made homeless in Toshima ward, for example, 60,875 were provided with temporary accommodation at eleven schools, three universities, two private residencies, and a temple.72 Jurinji Temple accommodated 900 people and became the new headquarters of Ikebukuro Police Station, which had been destroyed in the fires.

Deprived overnight of their homes and possessions, the survivors faced formidable hardships. With all the familiar landmarks gone, many had great difficulty even finding the ruins of their homes on the morning of April 14. One recognized his house from the shape of his air-raid shelter, another from the remains of the foundation stones. Once they had located the site, they started digging for anything they could salvage. The novelist Yoshimura Akira described the scene: “Many of them were digging in the debris with grappling hooks or shovels. They looked like people scavenging on a dry beach at low tide. Following their example, I started foraging for anything that could be used, but it was hopeless. The teacups and plates retained their original shapes, but the intense heat had made them too fragile and they crumbled in my hands. The pots and pans had melted into weird shapes.”73 With no fuel, electricity or running water, the survivors cooked rice over fires that were still smoldering and collected water from burst pipes. 57 year-old Shoshi Kumao, vice-chief of a community council, recalled, “The rice my wife had left in the cooking pot was still there, so we cooked it in the smoldering embers, made a makeshift roof by attaching a burned metal sheet to the edge of the well, and invited our homeless neighbors to share our breakfast. We talked about the terrible events of the previous night.”74 Apart from the basic necessities, many people were heartbroken by the loss of prized possessions. Oguchi Tatsumi, a 17 year-old middle school student, expressed the frank feelings of a typical teenager in wartime Tokyo: “I felt an unbearable sadness and emptiness. At that time, when people lost their homes they would often say ‘a burden has been lifted’ or ‘now I’m the same as everyone else.’ Those kinds of comment would be featured in the newspapers to show the indomitable spirit of citizens on the home front. But when my house actually burned down and I stood in the ruins of my room, I felt devastated at the loss of all the books and magazines I had skimped and saved to buy, particularly my greatest treasure – my collection of a dozen issues of Navy Club.”75 Some survivors mentioned the deathly silence that pervaded the ruins that night; all the familiar sounds of the city – the rattle of trams and the blaring of car horns in the distance – were gone. Shoshi Kumao was overwhelmed with sadness at having to leave Sugamo, where he had lived for 27 years. The next day, he and his wife joined the endless procession of refugees walking along the Shinkaido road to Saitama Prefecture twenty miles to the north.76

A sizable minority of victims decided to stick it out in the ruins, living in their air-raid shelters or in temporary shacks built from corrugated metal sheets and any other materials they could find. In Oji ward, not far from the Nissan Chemical Industries factory (Target 204), a shantytown of about 50 households grew up in the ruins. To earn a living, they undertook work repairing Nissan Chemical’s damaged factory as a joint project. To supplement food shortages, they received pumpkin seeds from Adachi ward and sowed them in the ruins. They also cultivated vegetables on a plot near the Arakawa River, growing potatoes, peanuts, radishes, cucumbers and tomatoes. Many people moved into the community and within three months the number of households had increased to 250.77 On May 5, the Nippon Times reported that 800 families in Toshima ward were living in air-raid shelters. The article humorously pointed out that, “even though a raid warning may be sounded, the shining advantage of life in a shelter is that one can remain quite composed.” Dry biscuits, emergency rice, and miso were rationed to the air-raid shelter occupants, who bathed together in the open in a stone public bath that had survived the fires. Their greatest problem was the draining and waterproofing of their shelters, particularly with the rainy season coming. “And so life goes on,” the article concluded, “with the people making the best of everything and even if it be life in a makeshift house underground, it is home to them.”78 These examples of life in the ruins are testimony to the extraordinary resilience of some Tokyo residents amid the most extreme hardships.

The people who continued to live in the burned areas outside the target zone for Perdition were actually in grave danger. Most of these areas, particularly those to the south of UIC 3600, would be firebombed again in the Great Yamanote Air Raid of May 25-26. That night Edogawa Rampo’s house in Ikebukuro again caught fire, but was saved once more by the brave efforts of his neighbors.79 In Kojimachi, Uchida Hyakken was not so lucky: his house finally burned down and he and his wife moved into a hut in the ruins. At that time it was not uncommon to be “dehoused” more than once. Tsukiyama Minoru, who lost his brother and two sisters in the March 10 air raid, moved with his parents to an aunt’s house in Katsushika ward. On the night of April 13-14, the house burnt down after a single B-29 unloaded its incendiaries nearby. It was so far from the target area that Tsukiyama later wondered whether the crew had simply wanted to get rid of their bomb load before returning to base.80 From around that time, people from different parts of Tokyo began greeting each other with the question, “How’s your house?” They would either reply with a sad shake of the head, or have to say guiltily, “Not yet.”81

Conclusion

The most striking characteristic of the April 13-14 air raid is the wide gap between the view “from the air” and the reality on the ground. Although the ostensible targets of Perdition were the Tokyo arsenal complex and the “urban-industrial concentration” in which it was located, it failed to inflict significant damage on the arsenal facilities and about half the area incinerated was outside the target zone. Furthermore, over 90 percent of the buildings reduced to ashes by the fires were civilians’ homes. They also included schools, universities, shrines, and hospitals. The raid must have killed or injured many “industrial workers”, but the great majority of the victims were women, children and the elderly. Nevertheless, senior airmen of the USAAF expressed satisfaction with the damage caused and even stated that the mission had been “carried out as planned.” Perdition was not simply an attack on industrial and strategic targets, as the Tactical Mission Report claimed, but an indiscriminate firebombing raid on an urban area. As such, it was the second in a series of five maximum-effort night raids on urban areas of Tokyo from March to May 1945. The forces used and damage caused by these attacks are shown in the table below.

| Maximum-effort Night Incendiary Raids on Tokyo Urban Areas | |||||

|

Date of air raid |

No. of B-29s |

Bomb tonnage |

Area burned (sq. miles) |

No. of dead* |

No. made homeless* |

|

March 10 |

279 |

1,665 |

15.8 |

83,793 |

1,008,500 |

|

April 13-14 |

327 |

2,120 |

11.4 |

2,459 |

640,932 |

|

April 15-16 |

109 |

754 |

6.0 |

841 |

213,277 |

|

May 23-24 |

520 |

3,646 |

5.3 |

762 |

224,601 |

|

May 25-26 |

464 |

3,258 |

16.8 |

3,242 |

559,683 |

|

Total |

1,699 |

11,443 |

55.3 |

91,107 |

2,646,993 |

| * Statistics of Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department | |||||

The April 13-14 raid (Perdition) accounted for about a fifth of the total 55.3 square miles of Tokyo incinerated and a quarter of the 2,646,993 people made homeless by these five firebombing raids. The number of people killed that night was comparable to the three attacks that followed it, but even the combined death toll of these four raids was only 7,304 people. The deadly combination of factors that killed an estimated 100,000 people in the early hours of March 10 would never be repeated. The death toll of that air raid alone was higher than the total number of people killed by all the other 92 urban firebombing raids on Japan during the war.82 In a relentless incendiary campaign that continued even after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nearly half the built-up areas of 67 cities throughout Japan were reduced to ashes. Apart from the Great Tokyo Air Raid, these other urban firebombing missions of the XXI Bomber Command have been largely forgotten.

|

Mimura Kazuo speaking at the Nezuyama Small Memorial Service, April 13, 2012. Source: Ikebukuro Television Corp. The video, with an English translation below it, can be viewed here. |

The only people who remember Perdition now are the survivors and the families of those who lost their lives. The Japanese survivors continue to gather in Minami-Ikebukuro Park on April 13 every year for the Nezuyama Small Memorial Service. It is a simple ceremony: two or three participants recount their experiences and the meeting closes with communal singing. On April 13, 2012, it was Mimura Kazuo’s turn to tell his story. Sixteen years old at the time of the air raid, he was now eighty-three. That year the cherry trees bloomed late, just as they had in April 1945. As Mimura spoke, cherry blossoms drifted down from the branches above. He told how, soon after the air raid began, a young mother with a baby on her back ran into his family’s house in Sugamo and sat down on the floor, trembling with fear. She held out a tiny woolen hat and asked Mimura to put it on her baby’s head. Together with his father and sister, Mimura escaped holding the young mother’s hand, but in the panic and confusion they became separated. The next morning, on the way back to the ruins of their house, they found the charred bodies of the mother and baby on the pavement. Fighting back his tears, Mimura said this greatest regret was that he had not held her hand more tightly.

All material from Japanese sources has been translated by the author.

Notes

Quoted in Michael Sherry, The Rise of American Air Power: The Creation of Armageddon (Yale University Press, 1987), p. 248.

Tokyo on November 29-30, 1944, and Nagoya and Kobe, on January 3 and February 4, 1945, respectively.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS), Field Report Covering Air Raid Protection and Allied Subjects, Tokyo, Japan (Civilian Defense Division, March 1947), p. 155. The USSBS estimate is 644,040 people, based on an “average of 4.5 persons per home,” but considering the wartime decline in Tokyo’s population, this average is too high. My estimate is based on 3.5 persons per home.

According to TMR 67, the 73rd and 313th Wings started bombing at 11.18p.m. and 11.23p.m., respectively.

The fires destroyed the red brick university building and the auditorium section of Building No. 1 was burned out. Most of Building No. 1, however, survived the fires and it is still in use today.

Daietsu Kazuji, Tōkyō Daikūshū ni okeru Shōbōtai no Katsuyaku (Efforts of the Fire Brigades in the Tokyo Air Raids; 1957) p. 299.

The lengths of the six air raids were: February 25 (114 minutes), March 10 (173 minutes), April 13-14 (219 minutes), April 15-16 (133 minutes), May 24-25 (119 minutes), May 25-26 (155 minutes).

Torii Tami, Shōwa Nijūnen (Showa 20; Shisosha Bunko, 2015), Vol. 8, p. 9; Yomiuri Shimbun, ed., Shōwashi no Tenno (The Showa Emperor; Chuko Bunko, 2011), Vol. 2, p. 111.

Tōkyō Daikūshū no Zenkiroku (Complete Record of the Tokyo Air Raids; Iwanami Shoten, 1992), p. 112. Ishikawa was on friendly terms with the Superintendent-General, so he may well have had access to confidential information.

Kido Koichi, Kidō Kōichi Nikki (DIary of Kido Koichi; Tokyo Daigaku Shuppankai, 1966), Vol. 2, p. 1194.

USSBS, Economic Warfare Section, War Division, Department of Justice, Confidential Report, June 30, 1943, “Re: The Shibuya, Shinjuku and Ikebukuro Stations, Tokyo, Japan”.

Nippon Times, April 16,1945. The rebuilding of Meiji Shrine after the war was finally completed in 1958.

See John Dower, Japan in War and Peace (New York, 1993), pp. 76-80. The Americans were of course aware of the existence of Riken Institute, but did not find out about Japan’s atomic bomb project until after the war.

See Frederick S. Litten, “Starving the Elephants: The Slaughter of Animals in Ueno Zoo”, Asia-Pacific Journal, September 21, 2009.

Saotome Katsumoto, Haroran no Tōkyō Daikūshū (Halloran and the Tokyo Air Raids; Shin Nippon Shuppansha, 2012), p. 44.

Aoki Tetsuo, “1945 Shigatsu 13-14 Tōkyō Kūshū no Mokuhyō to Songai Jittai” (Aims of and Damage Caused by the Tokyo Air Raid of April 13-14, 1945), Seikatsu to Bunka (Life and Culture) Vol. 15, 2005, p. 3-19.

USSBS, Entry 59, Security-Classified Damage Assessment Reports, 1945; Tokyo Report No. 3-a (20), 4 June 1945: Preliminary Damage Assessment Report No. 2.

USSBS, Damage Assessment Report No. 81 (June 7). The Tokyo arsenal complex remained on the target list and was bombed again on August 8 (Mission 320) and August 10 (Mission 323).

USSBS, Headquarters 20th Air Force (Chemical Section) Special Report on The Incendiary Attacks Against Japanese Urban Industrial Areas (December 13, 1945).

USSBS, Analysis of Incendiary Phase of Operations against Japanese Urban Areas, Report No. 1-c (30), p. 30.

For victims’ accounts of the inferno on Kototoi Bridge, see Richard Sams, “Saotome Katsumoto and the Firebombing of Tokyo,” Asia-Pacific Journal, March 16, 2015.

USSBS, Index Section 7, Entry 47, Security-Classified Joint Target Group Air Target Analyses, 1944-45: Targets in the Tokyo Area, Report No. 1.

Nissan Chemical Industries Company History Editorial Committee, Hachijūnenshi (80 Years’ History, 1969). Quoted in Aoki, op. cit., p. 17.

Nezuyama Small Memorial Service, Hisai Shōgenshū Dainishū (Victims’ Testimonies Vol. 2), p. 55-56.

USSBS, Field Report Covering Air Raid Protection and Allied Subjects, Tokyo, Japan (Civilian Defense Division, March 1947), p. 155.

Arima Yorichiku ed., Tōkyō Daikūshū Jūkyūnin no Shōgen (The Great Tokyo Air Raid: Nineteen Testimonies; Kodansha 1971), Matsuura Sozo, “Kakarezaru Tōkyō Daikūshū ” (The Great Tokyo Air Raid Nobody Writes About), p. 426.

Based on statistics in USSBS, The Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946, p. 33. The total number of people killed by the other 92 urban attacks is estimated to be 89,050.