In 2013 Sejong University Professor Park Yu-ha published a widely criticized book titled “Comfort Women of the Empire.” In her thesis, Park calls for a more complex and nuanced understanding of Korean involvement in the recruitment of comfort women and their varied experiences that challenges the prevailing victim’s narrative about this system operated by the Japanese military in the 1930s and 1940s (Park 2013).2 Leaving aside judgments as to the accuracy, or not, of Park`s research and assertions, the response was highly predictable, with massive grassroots and national-level condemnation quickly emerging given its direct challenge to the generally accepted conventional wisdom in South Korea regarding Japan`s colonial and war-time transgressions. Widespread, vocal disapproval was followed by a court order to pay 10 million won (roughly $8,262) to each of the remaining survivors for defamation of character (Choe 2016).

|

Park Yu-ha |

While Park Yu-ha was a political outsider, the next well-publicized, significant affront to the average Korean`s sensibilities came from the political establishment itself, when government representatives under President Park Geun-hye agreed to a deal with their former colonizer on December 28th 2015. In return for a new apology and $8.3 million in care assistance for the remaining survivors, South Korea, promised to not make future claims on Japan with regard to the Comfort Women issue. Yet again, the widespread negative reaction by grassroots organizations and opposition political elites in South Korea was not surprising given the sensitive, ‘powder keg’-like nature of this topic. While supporters might highlight the pragmatic nature of the agreement, general sentiment on the ground characterized it as an insult to national pride (see for example, Jun and Martin 2015). It appears President Park paid a steep political price as her party was hammered in the April legislative elections, losing a majority as disaffected voters gave a thumbs-down on her ruling style, the stagnant economy and what was regarded as an ignominious capitulation on the comfort women that injures national pride.

|

|

| Foreign Ministers Reach Comfort Women Accord in December 2015 | |

|

The comfort women accord has drawn widespread criticism in South Korea |

While Park Yu-ha`s book and the December 28th agreement went against popular nationalist sentiments in South Korea, political activist Kim Ki-jong`s attack on Mark Lippert in March of 2015, in protest at joint American-South Korean military exercises, arguably won him at least more moral support than the previously mentioned examples. Kim Ki-jong had earlier been convicted in 2010 for assaulting a Japanese envoy (Choe and Sheer 2015).

To be sure, Park Yu-ha`s publication, coupled with the bi-lateral agreement on the issue of Comfort Women, and the actions of Kim Ki-jong are largely on opposite sides of the left-right political spectrum. Collectively however, they highlight the passions that drive nationalism in modern Korea, and the significance thereof, which is the topic of this article. More specifically, this article examines the emergence, evolution, and political salience of South Korean nationalism in the post-1945 era with a focus on how it has, in all its dynamic forms, manifested itself prior to, and following, democratization in the 1980s. The first section elucidates how nationalistic passions were both manipulated and suppressed by successive authoritarian regimes. The second section deals with democratic South Korea and how grassroots nationalism influences domestic politics and government policies regarding the inter-Korean conflict, anti-Japanese sentiments over historical legacies of colonialism, and the emergence of anti-American activism.

Manipulation and the Suppression of Passions: 1945-1987

Having served much of its early history as a tributary state to China, Korean national identity emerged as a politically salient, modern manifestation of, and reaction to, Japan’s 35 years of colonial rule (1910-1945). Post-colonial political development in Korea is thus intrinsically affected by a collective sense of injustice inspired by unresolved grievances of colonial subjugation.

Following Japan’s wartime capitulation and liberation from colonial rule in 1945, the peninsula was thrown into what can be characterized as a stateless period under U.S. military rule-chaotic, rife with crime and unemployment, and a collapsed economy. Although stateless, it was not without its state-seekers-those who were vying to take part in the shaping of Korea’s post-colonial trajectory. Nationalist groups active during the colonial era, and those that rapidly emerged in the post-colonial political vacuum, fractured along principally a left-right ideological divide that subsequently became a North-South split.

|

|

| The Cheju massacre in 1948-49 by rightwing Koreans who collaborated with Japan also implicates the US | |

The origins of the left-right fissure in the peninsula was principally the consequence of the colonial period in which the rightists (made up principally of a wealthy and relatively well-educated elite) were the clear minority, having in some form or other collaborated with the colonial power in order to secure their privileged status and the access it facilitated. That the rightists were the minority and suffered from legitimacy concerns-both in terms of coercive capacity and popular support-is clear.

The overwhelming majority of Koreans aligned with the left. They were poor and agrarian with an overall rural population of just over 88%, as late as 1944. Furthermore, 99% of the employed women and 95% of the employed men were working as cheap laborers (Henderson 1968, 75). General distrust, if not outright disdain of homegrown rightists was such that in order to avoid the odium of past collaboration (and thus gain at least some semblance of popular legitimacy), the rightists had to look outside the peninsula-choosing exiled nationalists and staunch anti-communists such as Rhee Syngman and Kim Koo-to lead their cause.

|

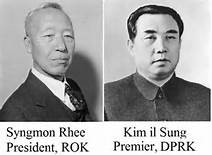

Bolstered by the presence and support of American forces in the South, the rightists consolidated power, however tenuous, under Rhee Syngman who was officially elected to power in May of 1948, with the Republic of Korea (ROK) being inaugurated in August of the same year. The leftists had already consolidated power in the North through the creation of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) under the Soviet- supported Kim Il Sung. The two newly formed republics would eventually collide in an all out fratricidal war from 1950 until 1953 when an armistice was signed. The two countries are still technically at war.

Although this paper is specifically about South Korean nationalism, it is important to note that the political elites on both sides of the peninsula have attempted to appeal to ethnic-nationalist, consanguineous sentiments to legitimize their respective claims and reunify the peninsula. Both sides continue to base their rapprochement policies on re-uniting what is perceived by many to be an ethnically homogenous ‘Han’ race.

In the ROK, nationalism draws on on a state-sponsored anti-communist ideology, while in the DPRK nationalism is based on state-sponsored anti-imperialist ideology. Both regimes trade accusations about being mere puppets of foreign regimes (Shin and Chang 2004, 127). Nationalism also had a local flavor as in the DPRK Kim Il-sung advocated ‘Juche” (‘self-reliance’) in response to Rhee Syngman’s ‘Ilmin juui’ (‘one-people ideology’).

Throughout the post-colonial period in the South, suppression and/or outright elimination of anti-government elements was carried out with swift brutality and efficiency. The government relied extensively on the sweeping powers of the National Security Law (NSL) created in 1948. This law was invoked to suppress criticism against the South Korean regime and the United States. Within a year of enacting the NSL, the South Korea government arrested 118,621 individuals for violations of the law and conducted massive purges of organizations including but not limited to political parties (Lee 2007, 82).

Through such repressive measures Rhee maintained control until he was finally forced out of power in the wake of unpopular national elections, mass demonstrations, and ultimately the loss of police and military support in 1960. Following a brief interim government, Gen. Park Chung-hee ascended to power through coup d’état in 1961. In doing so, Park espoused his own nationalistic rhetoric to establish popular legitimacy and justify his version of authoritarian management. He advocated continued suppression of anti-government progressives, economic development and more robust security capacity in order to achieve reunification of the ‘nation’ on Seoul’s terms. (Jang 2010, 95)

|

In 1961 Park Chung-hee seized power in a military coup and ruled until his assassination by the KCIA chief in 1979 |

The prerequisites for growth

Park Chung-hee came to power making promises of securing the ‘nation’ from Northern aggression and achieving economic industrialization and development. During Park’s tenure South Korea evolved from a military junta (1961-1963), to quasi-democracy (1963-1972) and finally institutionalized authoritarianism in 1972, all the while enhancing the state’s compliance-inducing capacity while largely delivering on his initial promises of a stronger military and robust economic growth. Such a transition resulted in a state that was, according to Woo (1991), “iron fisted at home and, therefore, capable of restricting the domestic economy and supporting sustained growth” (116). Between 1971 and the year preceding Park’s assassination in 1978, South Korea’s Gross National Product (GNP) per capita increased from US $288 to US $1,393, while recording a GNP growth rate averaging 9.8% (Oh 1999, 62).

The ‘iron-fist’ that Woo refers to was frequently employed in order to push through politically sensitive policies against popular opposition. Discontent and its suppression were features of rapprochement with Japan-both leading up to and following the signing of the controversial Normalization Treaty in 1965 that flew in the face of widespread anti-Japanese nationalist sentiments. Although the South Korean regime received an agreed upon $800 million in a mix of grants, loans, and credit from Japan (Woo 1991, 87), this deal sparked widespread condemnation by anti-Japanese forces and more than six months of extensive protests, hunger strikes, and even a funeral service for “nationalist democracy” (Lee 2007, 31). This agreement remains controversial in the 21st century as Seoul renounced all further claims to compensation from Japan. In 2005 the controversy was further complicated following the release of previously classified documents which revealed that South Korean delegates had rejected Japan’s offer for individual compensation to victims in favor of lump sum ‘state-to-state’ payments which the government channeled into state-led development projects (Park 2007, 69). Regardless of the benefits to the economy, it is hard to imagine that such a treaty could have been signed had South Korea been a liberal democracy at the time.

|

1965 Agreement normalized relations between ROK and Japan |

In addition to pushing through widely unpopular normalization of relations with Japan, provoking accusations of neocolonialism, the U.S. maintained its position as South Korea’s staunchest ally. Maintaining such relations and securing the support of the U.S., however, was not without its costs, as Seoul committed more than 300,000 troops to fight with America in the Vietnam conflict (Cumings 1997, 321). In return, the U.S. continued to help finance Korea, Inc.

|

300,000 South Korean soldiers served alongside the US in the Vietnam War, here being welcomed home |

DEMOCRATIZATION AND THE MAKING OF MINJUNG.

In 1972 Park Chung-hee instituted his ‘Yushin’ (revitalization/restoration) constitution-drawing on Japan’s Meiji Restoration and ‘Fukoku Kyohei‘ (‘enrich the country, strengthen the military’) mantra. This reform, similar to that of his 1961 military power grab, was framed as a ‘patriotic mission,’ necessitated by an unstable and precarious domestic and international environment (Shin 2006, 103; see also Choi 1993, 27).

Despite the nod towards constitutional government, Park’s move effectively institutionalized authoritarianism and further enhanced his control over the South. Paradoxically, Park’s success at maintaining power by all necessary means and successfully promoting industrialization actually undermined the authoritarian system. His policies inadvertently sowed the ‘seeds of democracy’, spawning a popular backlash aimed at realizing accountability, the rule of law and an empowered civil society. (Chang 2008, 33, 36). Widespread disdain for Park’s Yushin Constitution served as a basis for collective action against the government.

Despite (or perhaps because of) continued authoritarianism, South Korea’s economic motor continued to fire on all cylinders, which had significant implications for the emergence of pro-democracy forces. In conjunction with the economic gains noted above, mass education expanded as well. For instance, from 1960 to 1980, middle and high school student enrollments increased from 802,000 to 4,169,000. College level enrollment in turn swelled from roughly 100,000 to just over 600,000 during the same time frame. By 1990, the number of college students would surpass the one million mark (Oh 1999, 66). Importantly, students were the most prominent group in the democracy movement during the 1970s. (Chang 2008, 33, 36). In the 1980s, the newly emerging and increasingly politicized and contentious middle-class would join students, along with journalists, laborers, and religious organizations in their collective efforts in bringing about real political change and claiming a right to have a voice in forging the national agenda. Despite the state’s concerted effort at instilling anti-Communism as the main and only acceptable ideology, continuous repression spawned a new Korean identity and national consciousness under the banner of anti-authoritarianism.

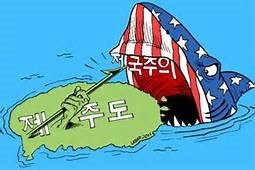

With the state-sponsored ideology of anti-communism losing its grip and society increasingly focusing its efforts on removing the authoritarian power structure, South Koreans began to question the role of the United States in not only supporting the dictatorship, but more broadly, in perpetuating the division of the peninsula. This was especially so following the Gwangju uprising where up to that point, noted “anti-Americanism had been about as common in South Korea as fish in the trees” (Henderson (1986) as quoted in Shin 2006, 168). The Gwangju uprising is frequently cited as being a key turning point in terms of the evolution and embrace of anti-American nationalism. (Lee 2007, 116)

|

|

| Gwangju Massacre 1980 | |

In late 1979 martial law was declared in the often-contentious southern region in the face of anti-government protests following the removal of Kim Young-sam from the National Assembly. Kim Young-sam (along with Kim Dae-jung) was a perpetual thorn in the side of the authoritarian leadership. Shortly thereafter, the director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) assassinated Park Chung-hee creating a vacuum of power that facilitated General Chun Doo-hwan’s power grab. Chun unleashed state security forces and cracked down on the protestors, sparking further protests centered most prominently in Gwangju, the then capital of South Jeolla province in the southwest. In suppressing this challenge, Chun employed the special warfare troops (those not under the U.S. controlled Combined Forces Command), resulting in the killing of hundreds of protestors and mass arrests in 1980 (Cumings 1997, 378).

Although the troops that carried out the violent campaign against the Gwangju protestors were not under the command of the U.S. (as most ROK troops are even now), Washington was seen to be complicit and guilty of a ‘moral failure’ (Woo-Cumings 2005, 70). Indeed, despite this bloody crackdown, Chun Doo-hwan, Korea’s new military dictator, received active support from the U.S. Carter Administration as the Ex-Im Bank guaranteed massive loans in June 1980 that served as an endorsement and President Ronald Reagan subsequently invited him to the White House in February 1981 (Scalapino 2004, 31). Thus, many activists became embittered towards the U.S. They identified the Americans as the main power behind the dictatorship, and barrier to both democracy and rapprochement with North Korea. As a result, there were a number of protests and attacks throughout the 1980s against American targets (Drennan 2005, 297).

In addition to the Gwangju uprising, Chun Doo-hwan faced a populist, quasi-Marxist but clearly anti-authoritarian challenge in the form of what was termed the minjung (literally the ‘people’s’) movement. Based largely on a new ideology of class-consciousness, which had evolved in the wake of rapid industrialization and repression beginning in the 1970s (but manifesting itself most prominently in the 1980s), this movement brought together an alliance of students, intellectuals, labor, peasants, elements of the emerging middle class, and other social groups. Such groups, although hailing from different sectors, shared a collective, nationalistic identity rooted in alienation from state power-whether the authoritarian regime or the United States (Koo 1993, 143-45). Minjung ideology, thus, became the basis of the pro- democracy movement that gained momentum in the 1980s, eventually toppling the authoritarian system.

|

Chun Doo-hwan, another military strongman, enjoyed US support |

In 1987 South Koreans, through a massive concerted effort, finally realized the political reform they had been demanding when Chun Doo-hwan stepped down and paved the way for a return to popular presidential elections and political liberalization. Roh Tae-woo became president in 1988 and promoted the democratic transition, as in 1993 Kim Young-sam became the first elected civilian president in three decades. Since then, power has oscillated back and forth between progressives and conservatives, which in turn has had a significant effect on various forms of grassroots nationalistic sentiment and activism, and South Korean foreign policy. With South Korea firmly in the democratic camp, such top-down control and manipulation of nationalism, as occurred during the dictatorship, was no longer possible. Democratization brought the public to the forefront and politicized nationalist issues, forcing politicians and bureaucrats to respond with policies that appealed to nationalist sentiment (Rozman 2010, 70-71). In addition, the proliferation of civil society organizations and social media has transformed South Korea into a vibrant democracy in which government policies and actions are carefully scrutinized and nationalist sentiments easily aroused.

Democratized Korea: Grassroots Nationalism and its Affects on Foreign Policy

Although there are a number of competing definitions for, and measures of democracy, basically it entails contested, free and fair elections, inclusion of naturally plural societal preferences, and peaceful, widespread participation in the political process. That South Korea has moved into the democratic camp is clear, and that move has importantly opened up previously closed institutional channels to power. Furthermore, since democratization was realized in South Korea, nationalism has taken on a number of new dimensions and directions in an environment where citizens no longer fear being imprisoned (or worse) for voicing their opinions.

Nationalism and inter-Korean relations

After industrialization and democratization in the South, in conjunction with the collapse of the Soviet Union, end of the Cold War, and periods of famine and economic decline in the North, a massive political and economic gap has emerged between the peninsula’s two competing polities.3 Furthermore, with the end of the military regime in the South came a shift in inter-Korean rapprochement policies, which have oscillated back and forth along the progressive-conservative spectrum. Even so, the framing of the unification question continues to be shaped by the belief (real or perceived) in ethnic-national unity between the North and South.

|

Sunshine Policy: President Kim Dae Jung meets Kim Jong-il |

The major shift in South Korean policies vis-à-vis North Korea came with Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy, which was based on reconciliation, reciprocity, and economic cooperation rather than on the ideological battle that had previous shaped relations. Kim Dae-jung’s approach paved the way for a summit meeting with Kim Jong Il in 2000, which in turn led to an expansion in various forms of inter-Korean cooperation. Following Kim Dae-jung, Roh Moo-hyun followed suit with his own brand of progressive conciliatory moves towards inter-Korean relations. Reflecting South Korea’s newfound space for healthy political pluralism, the progressives lost power in 2008, giving way to conservative Lee Myung-bak, and most recently in 2013, to Park Geun-hye, the daughter of former President Park Chung Hee. Despite frequent bellicose actions by both sides, and barring a collapse of the DPRK, the current situation of limited inter-Korean relations suggests that the peninsula will remain divided for the near future.

Anti-Japanese nationalism

In democratic South Korea the unresolved grievances of the colonial past have become exceptionally politicized in ways that have undermined bilateral relations in significant ways. The government may want to make concessions and pursue negotiations aimed at improving ties, but this is very difficult in an atmosphere where injustices of the colonial period cast a long shadow into the 21st century. Since taking office in 2013, President Park Geun-hye repeatedly admonished Prime Minister Abe Shinzo to embrace a correct understanding of history as a precondition for a summit even as polls show that the public supports dialogue and improved relations. But because Park is the daughter of the former Japanese collaborator who signed the infamous 1965 normalization treaty that many South Koreans think was overly generous to Japan, the situation is awkward, and especially so in the wake of the December 28th agreement.

|

Park Geun-hye, ROK’s embattled president

Back in 1998 Kim Dae-jung and Japanese Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo inked a wide- ranging agreement intended to launch a new partnership, but subsequently relations have not improved significantly primarily due to differences over the shared past. Koreans feel that Japan has not been sufficiently contrite about its colonial misdeeds, complaining that apologies have been limited and stopped short of admitting legal responsibility, while even limited apologies were repeatedly coupled with swift undermining by repudiating comments by Japanese conservatives.

The issue of the ‘comfort women’ forced to serve as wartime sex slaves for the Japanese military has been an especially divisive issue which has become increasingly complex following South Korea`s move towards the democratic camp. In 1995 the Japanese government helped establish the Asia Women’s Fund to provide compensation for the former comfort women, but civil society organizations in South Korea opposed this gesture of atonement because it did not admit state responsibility for the comfort women system. In 2011 the Constitutional Court ruled that the government had violated the rights of former comfort women by not pressing Japan to take state responsibility and provide redress, thereby forcing the most pro-Japanese government since Park Chung-hee to aggressively pursue the matter. This undid much of the good will that had developed since 2002 when South Korea and Japan co-hosted the FIFA World Cup. Osaka-born President Lee Myung-bak grew so frustrated with Japanese stonewalling that he became the first Korean leader to land on Dokdo in 2012, the disputed islands that became globally famous at the 2012 London Olympics when a South Korean football player brandished a banner declaring “Dokdo is ours”; this nationalistic gesture kept him off the medal awards podium, but earned him a coveted exemption from national military service.

|

|

| In 2012 Dokdo dispute derailed ROK-Japan Relations | |

While nationalistic passions run high and anti-Japanese sentiments are arguably a touchstone of national identity, in the wake of the March 11, 2011 tsunami that devastated northeastern Japan, South Korean charities raised more money than anywhere else for Japan in the first few weeks after the disaster. But the warmth and donations quickly faded when the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs adopted a more assertive position regarding the territorial dispute over the Dokdo/Takeshima islands. Thus, Japan remains South Korea’s favorite bête noire, and politicians often play the history card to boost sagging support in public opinion polls, underscoring the nexus of democracy and nationalism.

Recent surveys conducted in 2014 in Korea by the East Asia Institute (EAI) and the Genron NPO found that 70.9% of those polled (n = 1004) had an unfavorable impression of Japan (down from 76.6% in the previous year). The three main reasons cited for the negative perceptions included: (a) inadequate repentance over the history of invasion; (b) continuing conflicts on the issue of Dokdo, and; (c) unfavorable words and actions by Japanese politicians.4 Without passing judgment as to the quality and/or sufficiency of Japan’s attempts at resolving past and present issues with South Korea, recent nationalistic moves by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s government (e.g. issues related to comfort women, on-going territorial claims, visits and/or tributes to Yasukuni Shrine, and constitutional revision, textbooks, etc.) and apparent tolerance of Japanese right-wing hate speech targeting ethnic Korean resident in Japan have certainly not helped matters.

|

|

| Unapologetic Japanese PM Abe Unpopular in ROK | |

Under successive authoritarian regimes that ruled until 1988 anti-Japanese passions were suppressed. It is only in the democratic era that the past has been exhumed with a vengeance, as civic groups and politicians demand a more forthright reckoning from Japan that stokes nationalist sentiments in ways that constrain diplomatic maneuvering. In a democratized setting, mobilization of votes and support by appealing to anti-Japanese sentiment has become a popular tool of both power-holders and power-seekers, but as President Park has discovered, doing so cannot rescue an unpopular president.

Prior to democratization, the authoritarian government was able to exercise significant leverage over outpourings of anti-Japanese sentiment to secure Japanese economic assistance. Leading up to Prime Minister Nakasone’s visit to Korea in 1983, the South Korean government moved to ban from TV and radio the song “Dokdo is our Land,” along with the suppression of other types of grassroots activism that had the potential of exacerbating the already tense relations. Significantly, during this historic state visit Nakasone committed $4 billion in Japanese loans, facilitating further Japanese-South Korean meetings and a deepening of economic relations. (Choi 2005, 469)

In contrast to the authoritarian period, since the 1990s, the “Dokdo movement” has become a favorite focal point of NGO and political action. Groups such as the National Headquarters for Defending Dokdo, the Korean Dokdo Research and Preservation Association, among many others, frequently pursue: (a) legal strategies aimed at strengthening South Korea’s claim over the islands; (b) stage protests, and (c) initiate petition campaigns that mobilize anti-Japanese nationalism. Politicians of all stripes are quick to burnish their nationalist credentials by grandstanding over the Dokdo controversy. (Korea Joongang Daily, Aug. 16th, 2011).

Anti-American Sentiments

Undoubtedly the role and general perception of the United States in South Korea complicates the issue of inter-Korean relations and the prospects for unification, as well as South Korean-Japanese relations, discussed above. If one were to rely solely upon modern Korean cinema as a barometer of anti-American sentiment, it would be easy to assume it was rampant. For instance, widely popular films such as ‘Welcome to DongMakGol’ often portray the United States government and military as being the main opponent to Korean ‘national’ independence and reconciliation. Other films have shifted the focus away from a one-sided depiction of North Korean atrocities during the war to shed light instead on U.S. transgressions during that violent period in the not too distant past.5

|

|

| Anti-US backlash in Seoul | |

Roh Moo-hyun’s election in 2003 arguably owed much to highly visible anti-American sentiment that has emerged in post-democratized South Korea, often triggered by the misbehavior of U.S. military personnel and/or joint-US-Korea training exercises. Roh, known for his criticism of the US-ROK alliance, catapulted into the Blue House due to popular anger fuelled by the US military court’s acquittal of two American soldiers who hit and killed two South Korean teenage girls while driving an armored vehicle. Other grievances remain salient, including but not limited to those perceived to be unfair trade agreements and practices as evidenced in the 2008 protests following the government’s reversal on a ban of US beef imports that had been imposed due to concerns over ‘mad cow’ disease.

Despite eruptions of anti-American nationalism in South Korea, opinion polls carried out since the 1990s point to South Koreans as having some of the highest levels of support for the U.S. in the region (see for example, Kim 2014).6 The U.S-based Pew Research Center finds that South Korean attitudes towards the US are generally quite favorable, rising sharply from 46% in 2003 to over 78% since 2009 and reaching 82% in 2014. Moreover, even when US-South Korean relations become strained as they do at times, anti-American activism has generally been non-violent and has not had a major impact on bilateral relations.

Conclusion

Korea is often called a ‘shrimp among whales.’ Among those frequently pugnacious whales, Korea has often played an important role in complex geo-political machinations involving superpowers. This looming presence, and a sense that affairs on the Korean peninsula are determined elsewhere, serves to bolster nationalist sentiments.

In the post-colonial era, nationalism has served as a source of legitimacy and political contestation that keeps the peninsula divided at the 38th parallel. In South Korea, authoritarian regimes manipulated nationalist sentiment with varying degrees of success to shore up legitimacy and suppress anti-authoritarian, anti-US, and anti-Japanese activism. The collapse of Communism as a real threat, however, coupled with the rise of the middle class and democratization, unleashed politicized nationalism.

In democratic South Korea, nationalism continues to manifest in terms of the inter-Korean conflict and debate over unification. As of 2016 the two countries are still technically at war, and Article 3 of the South Korean Constitution asserts that the ROK consists of the entire peninsula and adjacent islands, complicating any move towards reconciliation.7

Anti-Japanese and anti-American nationalism are more evident and subject to political grandstanding for electoral advantage. Popular nationalist sentiments have also escalated in social media, a political arena that lends itself to extremist positions that are quickly disseminated and influence public opinion. Government policies are also subject to critical scrutiny on social media, creating a democracy in which the government finds its room to maneuver on complex diplomatic issues circumscribed by nationalist activism. The state, politicians, civil society groups and activists orchestrate nationalism in ways that reward assertiveness and brinksmanship while portraying compromise and concessions as betrayal rather than the currency of diplomacy. Democracy in that sense may be complicating, even straining relations between South Korea, North Korea, Japan, the US and China.

China’s rise as an economic and political powerhouse is another factor that boosts nationalism given disputed historical legacies and contemporary economic conflicts between these neighbors. Korea’s previous status as a vassal state paying tribute to China remains, like the era of Japanese colonialism and the ongoing American military presence, an affront to national dignity and therefore a source of humiliation, resentment and desire for redemption.

Related articles

- Millie Creighton, Through the Korean Wave Looking Glass: Gender, Consumerism, Transnationalism, Tourism Reflecting Japan-Korea Relations in Global East Asia.

- Herbert P. Bix, “Showa History, Rising Nationalism, and the Abe Government.”

- Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “The Re-Branding of Abe Nationalism: Global Perspectives on Japan.”

- Mark Selden, Economic Nationalism and Regionalism in Contemporary East Asia.

- Vladimir Tikhonov, Transcending Boundaries, Embracing Others: Nationalism and Transnationalism in Modern and Contemporary Korea.

Sources:

Chang, Paul Y. (2008).Protest and Repression in South Korea, 1970-1979. PhD Thesis, Stanford University.

Choe, Sang-hun. (2016). `Professor Ordered to Pay 9 Who Said `Comfort Women` Book Defamed Them,` The New York Times 13 January. Available here. [23 January 2016].

Choe, Sang-hun and Shear, Michael D. (2015), ‘Mark Lippert, U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, Is Hospitalized After Attack’, The New York Times 4 March. Available here. [4 April 2015].

Choi, Jang-jip. (1993), Political Cleavages in South Korea. In: Koo, Hagen, ed. State and Society in Contemporary Korea, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp.13-50.

Choi, Sung-jae. (2005), The Politics of the Dokdo Issue.Journal of East Asian Studies. Vol. 5, pp. 465-494.

Cumings, Bruce. (1997),Korea’s Place in the Sun, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Drennan, William M. (2005), The Tipping Point: Kwangju, May 1980. In: Steinberg, David I., ed. Korean Attitudes Toward the United States. London: M.E. Sharp, pp. 280-306.

Henderson, Gregory. (1968),Korea: The Politics of The Vortex, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Jang, Won Joon. (Summer 2010), Multicultural Korea: South Korea’s Changing National Identity and the Future of Inter-Korean Relations.Stanford Journal of East Asian Studies. 10, No. 2, pp. 94-104.

Jun, Kwanwoo and Martin, Alexander. (2015), `Japan, South Korea Agree to Aid for `Comfort Women,` The Wall Stree Journal 28 December. Available here. [28 December 2015]

Kim, Jiyoon. (2014), National Identity under Transformation: New Challenges to South Korea.The Asan Forum [online]. Vol. 3, No. 1, Available here. [4 April 2015]

Kingston, J. ed(s). (2015). East Asian Nationalisms Reconsidered, London and New York: Routledge.

Koo, Hagen. (1993), The State, Minjung, and the Working Class in South Korea. In: Koo, Hagen, ed. State and Society in Contemporary Korea, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp. 131-162.

Lee, Namhee. (2007),The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Moon, Chun-in and Li, Chun-fi. (2010). Reactive Nationalism and South Korea’s Foreign Policy on China and Japan: A Comparative Analysis.Pacific Focus. Vol. XXV, No. 3, pp. 331-355.

Oh, John Kie-Chiang. (1999),Korean Politics: The Quest for Democratization and Economic Development, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Park, Soon-Won. (2007), The Politics of Remembrance: The case of Korean forced laborers in the Second World War. In: Shin, Gi-Wook, Soon-Won Park, and Daqing Yang, ed. Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation in Northeast Asia: The Korean experience. New York, NY, Routledge, pp. 55-74.

Park, Yu-ha. (2013). Chaegu wianbu: shikminjiji paewa kiokwi tuchang. Ppuliwaipali.

Porteux, Jonson. (2015). Post-colonial South Korean nationalism. In: Kingston, J. ed. East Asian Nationalisms Reconsidered, London and New York: Routledge. pp. 186-195.

Rozman, Gilbert. (2010). South Korea’s National Identity: Evolution, Manifestations, Prospects.On Korea. Vol. 3, pp. 67-80.

Scalapino, Robert A. (2004), Korean Nationalism: Its History and Future. In: Pollack, Jonathan D., ed. Korea: The East Asian Pivot. New Port, RI: Navel War College Press. pp. 23-38.

Shin, Gi-wook. (2006),Ethnic Nationalism in Korea, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Shin, Gi-wook & Chang, Paul Y. (2004), The Politics of Nationalism in U.S.-Korean Relations.Asian Perspective. Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 119-145.

Woo-Cumings, Meredith. (2005), Unilateralism and Its Discontents: The Passing of the Cold War Alliance and Changing Public Opinion in the Republic of Korea. In: Steinberg, David I., ed. Korean Attitudes Toward the United States. London: M.E. Sharp, pp 56-79.

Woo, Jung-en. (1991),Race to the Swift: State and Finance in Korean Industrialization, New York and Oxford: Columbia University Press.

Notes

An earlier version of this article was published in Jeff Kingston, ed. Asian Nationalisms Reconsidered. 2015. Routledge, pp. 186-195

Although the DPRK does not publish reliable national statistics, the CIA World Factbook cites estimates published by an OECD-sponsored study which puts the ROK’s GDP (in terms of purchasing power parity) at roughly 40 times the size of North Korea’s in 2012 (accessed on 03/24/2015).

The 2009 film, ‘A Little Pond’ centers its story around the massacre of upwards of 400 civilians by the U.S. military at No Gun Ri in 1950.

In the Pew Research Center’s Spring 2014 Global Attitude’s survey, in terms of the U.S.’s ‘biggest fans,’ South Korea came in third with an 82% favorable response rate, behind the Philippines (92%) and Israel (85%) (accessed on 04/01/2015).