The Kaesŏng closure in context

On February 10, 2016, the South Korean government announced that it would close the Kaesŏng Industrial Zone (KIZ) in response to the North Korean nuclear test of January 6th and the launch of a satellite on February 7th. The zone, sometimes simply called by the name of the adjacent city of Kaesŏng, had been the last tangible outcome of the historic first inter-Korean summit of June 2000, which later that year had earned one of its two participants, the South Korean president Kim Dae-jung, the Nobel Peace Prize. His counterpart Kim Jong-il, who hosted the summit, received none. He was compensated generously by what has been rumored to be millions of dollars from South Korea. The payment was allegedly facilitated by Hyundai.1 That is the same company that managed the Mt. Kŭmgang tourism project in North Korea, another successful joint project that has been frozen since 2008. Through its subsidiary Asan, Hyundai also built the Kaesŏng industrial zone.

|

Monument in front of the Korean War museum in Seoul: Two brothers meet on the battlefield. Note the obviously hierarchic relationship between the armed South Korean (left) and the unarmed and much smaller North Korean (right).2 Photo: RF |

The story of the summit is quite telling in many respects. It illustrates the Western perspective on North Korea in general, and on Kaesŏng in particular. Nelson Mandela once famously said that if you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy. This advice often seems to fall on deaf ears, notably with respect to North Korea. We tend to regard talking to and working with Pyongyang as a generous and precious gift. Each time the North Koreans agree to engage, we assume they do so only reluctantly. If we finally succeed in reaching an agreement, we regard this not as a win-win situation, but as a victory against or a generous compromise with a difficult enemy whom we do not trust and whom we, in the final analysis, want to defeat and destroy.

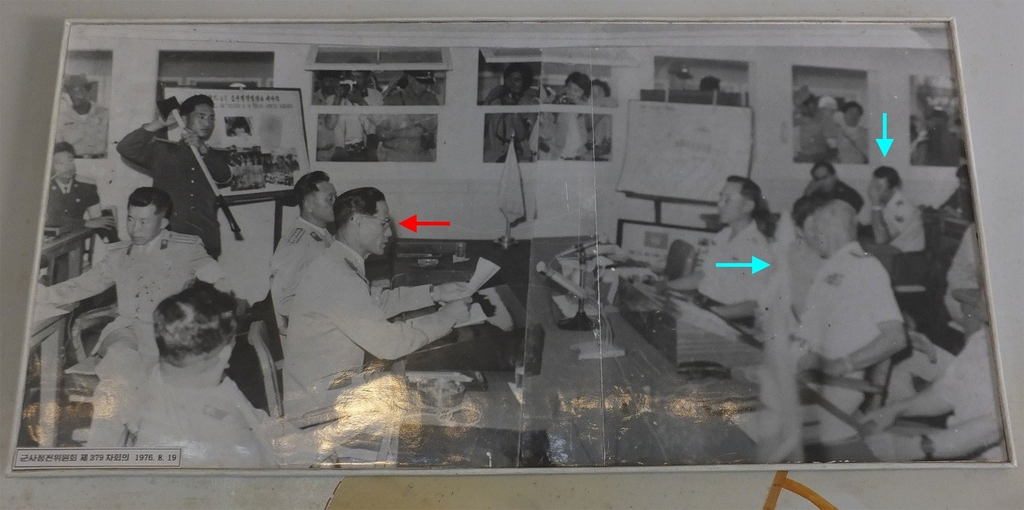

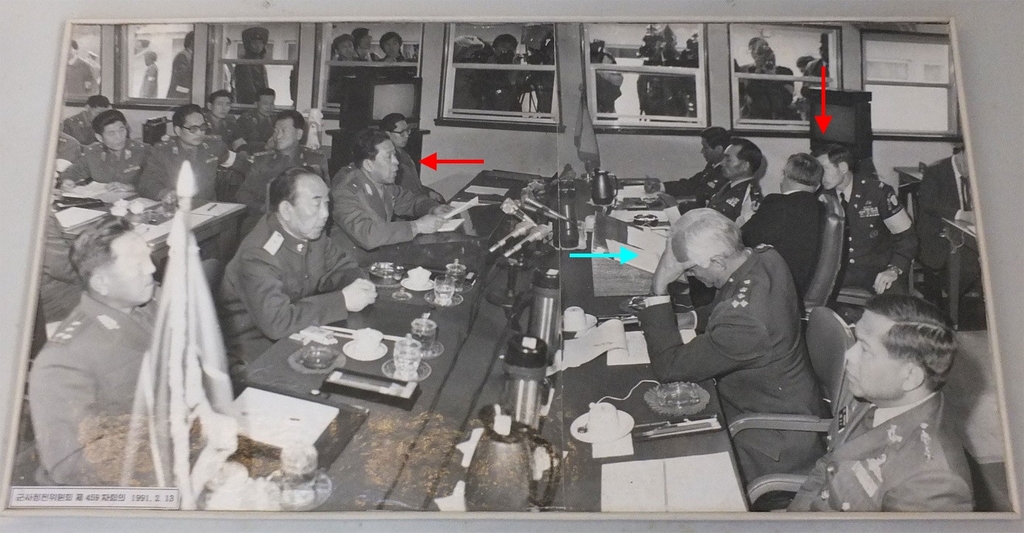

Ironically, the North Korean perspective on their dealings with the West is quite similar, the other way round of course. If you don’t wish to read North Korean history books or literature, just have a look at photos of negotiations that can be found in various museums around North Korea. The American negotiators are often pictured as either holding their head in desperation or turning to their staff for help, while the North Korean counterpart is calm, determined, and self-confident.

|

1976: 379th meeting of the Armistice Commission (negotiating the Axe Murder Incident) Photo: RF |

|

1991: 459th meeting of the Armistice Commission Photo: RF |

A quarter of a century after the end of Cold War I,3 the relationship between the West and North Korea is still mainly a matter of ideology. It is a war of words, of symbols, of gestures. Hard facts including military threats or economic costs and benefits are used if convenient, but they get easily discarded when found to be bothersome. The goal of both sides is political victory. For Washington and the current South Korean president, this explicitly means regime change in Pyongyang4. Kim Jong-un wouldn’t mind a regime change in Seoul, either. Both South Korea and North Korea want unification – on their respective terms. This is hardly a good foundation for sustainable cooperation. We should also not forget that often, the name of the real game is not US-Korean or inter-Korean relations; kicking North Korea often means China.

Not least, the story of the summit also shows the close connection between politics and the economy. For a system of state ownership like North Korea, this is self-evident. But even in the liberal market economy of South Korea, there is a tradition of large conglomerates sometimes acting as “private agents of public purpose”.5 It is difficult to understand and evaluate the events in and around Kaesŏng without considering both aspects.

The fate of the Kaesŏng Industrial Zone is part of a bigger story. Therefore, although the purpose of this essay is to discuss the effects of its closure, it will inevitably also run into the more general question of how to approach North Korea. Since perspective matters, we will start with an evaluation of the effects on South Korea, to be followed by a discussion of the effects on North Korea.

The balance sheet for South Korea

Winning or losing implies a positive or negative balance between the benefits and the costs of an action, and it requires a clearly defined set of goals. In addition to the above-mentioned issue of political versus economic effects, the question about who wins or loses is difficult to answer from the perspective of a whole country. The aggregate terms “North Korea” and “South Korea” are not very precise and subsume various groups of stakeholders who do not necessarily share the same goals and who might be affected very differently.

To start with South Korea, the Park Geun-hye government definitely won politically in the sense of showing that it is no longer willing to remain passive in the wake of what it regards as North Korean provocations. The list of such events is long and includes the sinking of the Ch’ŏn’an in 2010, the shelling of Yŏnp’yŏng Island in the same year, the mine blast at the DMZ in 2015, the four nuclear tests during these years, a number of missile and rocket launches which are seen as part of North Korea’s nuclear program, and many more major and minor incidents. Rather than turning the other cheek, Seoul decided to demand an eye for an eye. It dealt a blow to North Korea by eliminating a source of hard currency inflow into the country in the range of about 120 million US dollars annually.

However, the closure also entailed a cost for the South Korean government; this is the only way that we can reasonably explain that the zone had been kept open for such a long time despite the many actions listed above that were perceived as hostile. Unless Seoul deliberately and for many years acted against its own interests, it did not close the zone because it found it useful. Given the very peculiar political nature of the KIZ, the Blue House did, however, resist calls for the opening of a “second Kaesŏng” in North Korea by federations of South Korean SMEs6, which alone says much about the popularity of the Kaesŏng complex among business circles in Seoul.

Among the benefits was a large-scale, regular and unparalleled access to North Koreans. It is obviously important for policymakers in Seoul to know what is going on in North Korea; and although the 54,000 workers at the Kaesŏng zone were very carefully selected and thoroughly briefed by the North Korean authorities, interacting with them on a daily basis still constituted a very valuable source of intelligence for the South on the many small things that form a larger whole. To make matters worse, there are few if any alternatives. Information from defectors arrives with a significant delay due to their often arduous journeys, and information gathered in Northeast China suffers from a number of flaws including giving disproportionate weight to news from North Hamgyŏng province7 and the danger of for-profit production of allegedly authentic news by clever individuals.8 It is fair to say that because of the closure of Kaesŏng, South Korea now knows less about what is happening in the North.

The South Korean economy also suffered from the closure. Given economic complementarities between North and South Korea, Kaesŏng turned out to be very lucrative for South Korean businesses.9 124 companies brought raw materials and semi-finished goods to Kaesŏng, processed them with cheap North Korean labor, and re-imported them to the South. South Koreans were employed along the whole value chain of backward and forward linkages. The overall value of goods that were brought in and out of Kaesŏng was about 0.5 billion US$ in 2015,10 which was less than 0.04 percent of the South Korean GDP of over 1,400 billion US$. This will not bring down the economy, but the affected companies will have a hard time finding any alternative location for their production of labor-intensive light industry products such as shoes, textiles, watches etc. These industries cannot produce profitably in South Korea’s high-wage environment; if they are unable to operate in Kaesong, they need to find another low-cost place, or cease business. The statement of the manager of a firm at the zone that “hundreds of thousands of South Korean workers and families”11 will be affected might be an exaggeration, however it is fair to assume that a significant number of South Koreans will indeed suffer from a reduction in their incomes or lose their jobs.

This situation is even more complicated by the fact that China, one traditional place for such sunset industries to escape to, with steady annual increases in the state minimum wage, is now becoming too expensive itself and has begun outsourcing some of its own labor-intensive production to Southeast Asia and Africa. In addition, there is no other low-wage country except a few minority regions in China and Kazakhstan where Korean is spoken and communication between South Korean managers and their staff was thus relatively easy.

If we think about other stakeholders in South Korea, we could as well consider the whole population because tensions with North Korea increase the risk of war. This is not to say that the Kaesŏng closure will result in a North Korean attack; but it escalated a situation that is already on the brink, and it cut a few important communication lines that were used in the past to settle smaller issues before they could develop into bigger crises.

Regarding the effect of the Kaesŏng closure on unification, we are back to the more general discussion on how to deal with North Korea. Those who believe in unification as the result of engagement will say that the closure reduced the chances for unification. Those who think that the only way to reunify Korea is by making the North collapse and absorb it will point at the reduced inflow of hard currency and therefore regard the Kaesŏng closure as a step towards such a type of unification.

An interesting argument concerns South Korea’s leverage over China. By being tough on North Korea in the case of the Kaesŏng zone, Seoul can now more reasonably demand China to be tougher on NK, too. However, this is not equivocally shared by all experts. John Delury argues in the opposite direction: The South Korean president might have undermined her credibility with China by acting as a hardliner.12 This, and the fact that the Chinese were strongly in favor of the Kaesŏng zone as one open channel for regular exchanges, reduces Seoul’s influence in Beijing and leads Chinese analysts to blame tensions on the peninsula not only on the North, but also on the South.13

From a strategic perspective, by further severing ties with Pyongyang, Seoul risks a return to the Cold War I situation where the two Koreas were not seen as independent actors, but as parts of two opposing camps. Korea’s history is full of examples in which similar constellations led to endless suffering on the part of Koreans; think about the Imjin War 1592-1598 or the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95. In both cases, the Chinese and the Japanese fought on Korean soil over supremacy in Northeast Asia. The Korean War is just the latest, and arguably the most disastrous, in a long chain of such events. It is easy to interpret the North Korean insistence on “uriminjokkiri” (by our nation itself) as an attempt to disrupt Seoul’s alliance with Washington in preparation for another attack.

But the North Koreans are ultra-nationalists, and they think strategically. They neither trust the Americans nor the Chinese. Nor do they trust the Japanese. The museum in Sinch’on is filled with very graphic depictions of atrocities in the Korean War, but the perpetrators are always the Americans. South Koreans are spared this kind of exposure in the expectation of an eventual national unification that would enable all Koreans to defend the nation against hostile outsiders.

In this context it is interesting to note that the South Koreans seem to apply a similar strategy to explain why the announcement of the goal of regime change by President Park does not contradict her “Trustpolitik”: they emphasize the difference between the North Korean leadership and the North Korean people14. This separation of “people” and “leadership” is not a new idea; after World War Two, in an effort to justify cooperation with East Germany, Stalin famously stated that “Hitlers come and go, but the German people, the German state, they stay.”15

Back to the effects of the Kaesŏng closure on South Korean, the balance is in the eye of the beholder. We dare say that there is little room for optimism about a positive result, but perhaps we are looking at the wrong end of the equation and should rather turn to North Korea.

The balance sheet for North Korea

The same argument as for South Korea could of course be made for the North. They could have closed Kaesŏng anytime, and they actually did so for a few weeks in 2013, but then they opened the zone again. So Pyongyang’s assessment of the net benefits of the zone must have been positive, too.

Among the immediate reactions to the Kaesŏng closure there was unanimous agreement that the hard currency income from Kaesŏng was important for North Korea. We share this assessment. One of the weaknesses of economies like North Korea is that their currency is not convertible and thus worthless outside their own territory. In case of a shortage of funds for imports, the North Korean state cannot just order its Central Bank to print more money. Counterfeiting is not a sustainable strategy either. If the North Koreans want to buy something abroad, they need to generate hard currency through the export of goods or services, by receiving loans, or by attracting transfers such as aid, remittances of nationals working abroad, and so forth. North Korea generated valuable hard currency income from Kaesŏng through various fees, and by collecting the wages for the workers from their employers in US$ but paying them in local currency, which is more or less cost free for the North Korean state. We can thus count 100% of the wages as income for Pyongyang.

The overall amount of this income is provided by the South Korean government as 120 million US$. When it comes to data on North Korea, caution is due because of a general lack of precise information, and because political motives often dominate. The number of 120 million US$ might be somewhat overstated if we consider that 54,000 workers received at least 75 US$ per month, which makes roughly 50 million a year. But if we take the figure of 100 million US$ in annual wages16 at face value, the income from fees etc. could indeed be another 20 million, which coincides with the anecdotal evidence one of the authors has picked up in Kaesŏng.

So let’s assume the North Korean income from the Kaesŏng zone was indeed in the range of 120 million US$ annually. Is this a lot? Or to put it differently, what shall we use as a benchmark to find out the relative value of this amount for the North Korean government? Haggard and Noland suggest contrasting this number with the 450~750 million US$ of North Korea’s trade deficit with China, pointing at a relative weight of the income from Kaesŏng between 17 and 29 percent of that crucial deficit17.

Another option would be to look at overall exports. Following the same logic as above, the costs in local currency for the production of these exports do not matter, because the KPW is not convertible and can be printed or otherwise obtained at any time. In 2014, North Korea’s exports according to KOTRA were about 3.165 billion US$.18 Trade is about the only way North Korea can get hard currency; loans, bonds and other instruments are not available due to sanctions and international isolation. This means the income from Kaesŏng was about 3.8 percent of North Korea’s known legal exports. There is also the option of making money through illicit trade and of counterfeiting, but the low level of our media reporting about these issues suggests that such activities have either been significantly reduced in recent years, or are much better hidden, or both.

A third option might be to compare the alleged revenue generated by Kaesŏng for North Korea with the salaries paid by Chinese companies for North Korean workers in Northeast China. According to the official Chinese press, there are as many as 40,000 North Korean laborers working in the three Northeastern provinces of the PRC, with the total revenue for Pyongyang estimated at more than 140 million US$19, slightly above Kaesŏng. But these numbers have to be considered with extreme caution since even the official Chinese press mentions large numbers of North Korean workers being unofficially employed in China. What’s more, exporting labor and recreating “North Korean communities” abroad generates costs, which reduce the North Korean State’s net income to an unknown extend.

No matter which benchmark we apply, it is relatively undisputed that the income from Kaesŏng was not just a flash in the pan for the North Korean economy. The closure of Kaesŏng thus hurt; but did it hurt sufficiently, and will it hurt long enough to trigger a change of direction in Pyongyang? If history is a teacher, this is far from inevitable. What is more, the effects of the Kaesŏng closure will very likely be compensated quickly.

The options for such compensation are manifold.

First of all, the KIZ proved that long-term economic cooperation with North Korea is viable and lucrative, although often subject to political and diplomatic developments in the peninsula. China, North Korea’s biggest economic partner, is obviously the very first potential actor that comes to mind to replace the former South Korean partner. Given the different nature of a tourist resort and a light industrial park, it might be far-fetched to draw too close comparisons between the possible fate of Kaesŏng and what happened to the Mt. Kŭmgang project, but clearly North Korea does search for alternative partners if one business relationship deteriorates. In the late 1990s, Hyundai Asan built a resort and port facilities in the North Korean Mt. Kŭmgang area near the border. Almost two million mostly South Korean tourists visited the resort, earning North Korea hundreds of thousands US$ over the course of a decade.20 When in 2008, a South Korean tourist was shot dead, South Korea withdrew from the project.21 The North seized the facilities. In June 2011, North Korea promulgated a new law on the tourism zone22 and opened it to investment from other countries, targeting mainly Chinese tourists.23

The direct leasing of Kaesŏng facilities to new owners is unlikely given that the KIZ was powered by South Korean electricity, not to mention potential political turbulence that could strain the Beijing-Seoul political and economic relationship. But North Korea has accumulated enough experience to try and operate the park on its own. Given that rising Chinese wages are reaching the threshold of profitability, outsourcing parts of Chinese manufacturing industry to North Korea might provide interesting opportunities to Chinese businesses: minimum wage in the Yanbian Autonomous Prefecture of China, bordering North Korea, is 210 US$ a month, versus slightly more than 80 US$ in the Rajin-Sŏnbong Special Economic Zone on the other side of the border.

North Korea could further try to more actively use the opportunities offered by the 24 other special economic zones in North Korea. In which case some of the 54,000 Kaesŏng workers would be relocated to other places where they would essentially fulfill the same function as a generator of hard currency, only with different partners and perhaps also with slightly different products. As for North Korea, it could also have the positive spillover of diffusing technological and managerial know-how learned in Kaesŏng to other parts of the country.

Such an equation has two sides; the compensation of the income loss from Kaesŏng by expanding cooperation with the Chinese will only work if both sides cooperate. The statement by China’s foreign ministry spokesman Hong Lei that “sanctions should not affect the normal life of North Korean people” suggests a certain level of flexibility.24 China, which has seen its resource-hungry hyper-growth slowing down in recent months, seems to be willing to reduce the import of minerals from North Korea, especially when it concerns areas where North Korea could become a challenger to China’s near monopoly on the world market, in particular for rare earth metals.25

But it is not obvious that China would acknowledge a direct relationship between textile production26 and the North Korean nuclear program. While supporting the harshest sanctions to date on North Korea, China might be tempted to, on the other hand, boost its economic engagement with Pyongyang, in order to mitigate potentially dramatic effects, prevent the situation from spinning out of control, and to encourage economic reform in North Korea. However, we should note that Chinese economic engagement in North Korea has so far not nearly exhausted its full potential; this suggests that Beijing reserves more investment as a reward for reform and opening policies by Pyongyang. From this perspective, it is interesting to note that some analysts have suggested that the latest UNSC sanctions according to Resolution 2270 might be applied selectively by China.27

Another potential source for compensation is Russia. Its interests are slightly different from those of China.28 Russia suffers from a shortage of labor in its Far East and is thus unable to fully exploit its own natural resources there. The production of timber is among the most publicized instances.29 In October 2015, Russia’s Minister for Development of the Far East, Alexander Galushka, visited North Korea and discussed a number of projects for the expansion of economic relations.30 Sizeable investments from Russia have already been made in the infrastructure of the Rajin-Sŏnbong Special Economic Zone. As part of a trilateral project between South Korea, the Russian Far East and North Korea’s northeastern territories, it could provide a strong incentive for Moscow to push for an early resumption of inter-Korean economic exchanges.31 Considering the worsened relationship between Moscow and Washington over Crimea and Ukraine, it remains to be seen whether Russia would wholeheartedly join the West in more radical sanctions or rather use the North Korean card to retaliate.

Regarding the political effects of the Kaesŏng closure, two interpretations are possible.

National unification is not only the official goal of the North Korean government; it is a great source of hope for most North Korean citizens. The Kaesŏng zone was one of the few tangible steps towards reunification. It could thus be argued that the closure would not be welcomed among North Korea’s population, at least among those familiar with the project. In the unlikely event that this closure is seen as a consequence of Kim Jong-un’s policy, the effect on the legitimacy of the North Korean regime would be negative. However, this is not an overly realistic expectation given the still strong dominance of state media over public opinion and the fact that the zone was closed by Seoul, not by Pyongyang. In fact, South Korea’s initiative is likely to reinforce the official North Korean position that the Park government is an obstacle to national unification.

More importantly, the closure of the Kaesŏng Zone ended over a decade of ideological “poisoning” of tens of thousands of young workers, to use North Korean terminology. Whatever the reasons were – greed, naivety – the North Korean state risked a lot by exposing tens of thousands of young women from the countryside to a high-end South Korean working environment and daily contact with South Korean managers.32 Whoever has visited a typical North Korean factory and compared it with the clean, bright, propaganda-free33 and modern facilities in Kaesŏng with their stable supply of tasty snacks, electricity and clean, hot water can imagine the power of such a comparison. Experience from other socialist countries suggests that no ordinary ideological training sessions would have been able to hide the obvious material superiority of the South. The experience of former socialist countries in Eastern Europe suggests that the state’s attempts to explain this as a mere showcase, and to argue that such affluence even if it was real was earned at the price of selling one’s pride to foreign forces, will have fallen on mostly deaf ears.

The Kaesŏng closure put an end to the embarrassing practice of a socialist state openly selling its youth to Southern capitalists who exploited their workforce for profit. A similar pact-with-the devil policy by Erich Honecker in East Germany earned the state millions in hard cash, but in the end contributed to the collapse of a heavily delegitimized system whose claims of moral superiority merely sounded hollow in the ears of its citizens.34 One could argue that China has since 1978 been doing something similar without the same effect, but this is mainly due to the strongly reduced relevance of ideology there and the fact that most Chinese in these decades have achieved enormous economic success including rising incomes and reduction of the worst poverty. It remains to be seen how the slower growth and rising social tensions will be dealt with.

For North Korea, we should note that it is not Marxist-Leninist logic that is applied, but rather chuch’e-type nationalism. This is how the regime was able to justify cooperation with the South; in more official conversations of one of the authors with North Korean officials, it was usually emphasized that North Korean labor was helping the South Koreans in some kind of patriotic endeavor. Nevertheless, in private conversations, a sense of uneasiness with that situation was visible. It remains to be seen which effect will dominate: the loss of hard currency income, or the elimination of an ideologically problematic situation.

Conclusion

In light of the above, it seems fair to conclude that neither side clearly wins from the Kaesŏng closure, indeed, that both sides face losses. An assessment that prioritizes short-term economic effects and dismisses the losses to businesses involved in production in the zone would conclude that South Korea is better off; a focus on long-term political effects might favor North Korea. The actual net effect depends on a number of variables. These include the ability of North Korea to quickly compensate the loss of hard currency income from Kaesŏng, and the ability of South Korea to compensate the loss in terms of intelligence and propaganda. Finally, it remains to be seen whether the closure of Kaesŏng will indeed be permanent. The role of external forces, in particular China, matters as well. It remains doubtful, however, that Beijing, in the interest of making a measure taken by Seoul more effective, is willing to review strategic considerations that have so far led to a tacit support of Pyongyang despite disagreement of many of its policies.

Recommended citation: Rüdiger Frank and Théo Clément, “Closing the Kaesŏng Industrial Zone: An Assessment”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 6, No. 7, March 15, 2016.

Related articles

- Charles Armstrong, Interview: Seoul’s hardline response “plays right into North Korea’s hands”

- Rudiger Frank, Why now is a good time for economic engagement of North Korea

- Jae-Jung Suh and Taehyun Nam, Rethinking the Prospects for Korean Democracy in Light of the Sinking of the Cheonan and North-South Conflict

- Jeremy Kuzmarov, Bomb After Bomb: US Air Power and Crimes of War From World War II to the Present

- Morton H. Halperin, A New Approach to Security in Northeast Asia: Breaking the Gridlock

- Peter Hayes, Chung-in Moon and Scott Bruce, Park Chung Hee, the US-ROK Strategic Relationship, and the Bomb

- Jeffrey Lewis, Peter Hayes and Scott Bruce, Kim Jong Il’s Nuclear Diplomacy and the US Opening: Slow Motion Six-Party Engagement

Notes

A profound and elaborate discussion of this statue and other patriotic symbols can be found in: Sheila Miyoshi Jager: Narratives of Nation Building in Korea: A Genealogy of Patriotism

In a way, one could argue that the Cold War never really ended on the Korean peninsula. In anticipation of a second Cold War between great powers to emerge in the next years, we prefer to call the Cold War (1945-1990) Cold War I, following the terminology on World Wars I and II. See “Cold War 2.0 would benefit North Korea”, The Korea Herald, 01.06.2014,

“‘Regime collapse’ awaits North Korea, says South’s leader in nuclear warning”, The Guardian, 16.02.2016, accessed 26.02.2016.

Jung-en Woo: Race to the Swift. State And Finance In Korean Industrialization (Columbia University Press, 1991).

“Businessmen seek a ‘second Kaesŏng Complex’ in N. Korea”, The Hankyoreh, 05.02.2014, accessed 02.03.2016.

People-to-people exchange is particularly intense in this northeastern region of North Korea because of the relatively lightly guarded border with China and the close ethnic ties with a Korean-speaking minority in Yanbian province. It is no coincidence that Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy (Spiegel and Grau 2009) is based on a story from Ch’ŏngjin, the provincial capital of North-Hamgyŏng.

This is by no means to say that all of the information coming in that way is fake. However, it would be naive to assume that years of an obvious willingness to pay by South Korean and Japanese journalists and other information-seekers (demand) would remain without an effect on the supply side, i.e. inspire attempts by at least a few individuals to produce or manipulate evidence. Very often, the traumatic nature of the experience in North Korea and along the escape route has an impact on how the victims later present their memories. The case of Shin Dong-hyuk (“Escape from Camp 14”) who, after growing pressure admitted in January 2015 that some key facts of his story were not true, is one indicator of this phenomenon; the not uncontroversial personal story of Yeonmi Park is another one. See Mary Ann Jolley: “The strange tale of Yeonmi Park”, The Diplomat, 10.12.2014, accessed 03.03.2016.

“Gaeseong joint complex reaches $3 bln in accumulated production volume, 11 yrs after opening”, Korea Herald, 04.10.2015, accessed 02.03.2016.

“Shutdown of Kaesŏng Complex a possible response to North Korean rocket launch?”, The Hankyoreh, 05.02.2016, accessed 01.03.2016.

“After rocket launch, South Korea will shut down joint industrial park with North Korea”, LA Times, 10.02.2016, accessed 01.03.2016.

Kim Ga Young: “‘Trustpolitik’ should be not with Kim Jong Un, but the North Korean people”, Daily NK, 19.02.2016, accessed 26.02.2016.

“S. Korea tracks money flow over N. Korea’s Kaesŏng revenue use”, Yonhap, 15.02.2016, accessed 01.03.2016.

“The Kaesŏng Closure: North-South Trade over the Longer-Run”, Witness To Transformation, 19.02.2016, accessed 01.03.2016.

Kim InSung and Karin Lee: “Mt. Kumgang and Inter-Korean Relations”, NCNK, 10.11.2010, accessed 05.03.2016

Jonathan Watts: “South Korean tourist shot by soldier in North”, The Guardian, 12.07.2008, accessed 03.01.2016

“Law on Special Zone for International Tour of Mt. Kumgang”, KCNA, 02.06.2011, accessed 04.04.2012

“North Korea seeks Chinese tourists for Mount Kumgang resort”, The Telegraph, 01.09.2011, accessed 05.03.2016

“U.N. resolution must not affect normal life of N. Korean people: China”, Yonhap, 26.02.2016, accessed 26.02.2016.

North Korea became, in 2015, China’s most important foreign supplier of textile products, outranking Italy and Vietnam. 朝鲜首次成为中国最大服装供应国去年出口超6亿美元, QuanqiuFangzhi,05.02.2016. Last accessed 02.03.2016.

28

For a discussion of Russia’s interests and its position after UNSC Resolution 2270, see Georgy Toloraya: “UNSCR 2270: A Conundrum for Russia”, 38North, 05.03.2016, accessed 06.03.2016

Chad O’Carroll: “Russia and North Korea agree in principle to build joint trade house”, NK-News, 14.10.2015, accessed 25.02.2016.

“RZD says new U.N. sanctions might halt joint project with N. Korea”, Yonhap, 25.02.2016. Last accessed 02.03.2016.

A defector recently confirmed that people in North Korea have been discussing the working conditions at the Kaesŏng zone. See Je Son Lee: “I’m sad to see the Kaesŏng Complex go”, NK-News, 16.02.2016, accessed 18.02.2016.

To be precise, factories in Kaesŏng were free of North Korean propaganda, but not of posters put up by the South Korean employers that were seeking to instill the right work ethic among the employees.

Raj Kollmorgen, Frank Thomas Koch and Hans-Liudger Dienel (eds.): Diskurse der Deutschen Einheit. Kritik und Alternativen (Discussions on German Unity. Critique and Alternatives) (VS Verlag, 2011).