Summary

Alongside even larger numbers of contingents drawn from France’s colonial empire, including a large pool of workers sourced from China, successive contingents of “Indochinese” – Vietnamese in addition to Cambodians – were also pressed into both military and labor battalions in World War I battlefields. Besides explaining the battlefield experiences of the Indochinese battalions in the European war – a little studied area – this article seeks to expose the contradictions raised by France’s patriotic appeal for “volunteers,” versus the domestic anti-colonial movement. On another level, the article examines the juncture between the worker-soldiers in France and the burgeoning socialist and communist underground in Paris, and back home in Vietnam, as best exemplified by the activities and writings of Ho Chi Minh in the run-up to his now-famous oration at the Versailles Conference.

Introduction

Faced with early setbacks in World War I battles on the Western Front, alongside a massive attrition of manpower, France began to look to its empire and even China as sources of labor alongside soldiers. Eventually Indochina would supply some 30 percent of France’s colonial forces alongside even larger contingents of Senegalese, Madagascans, and Moroccans and Chinese, in all totaling about half a million.

|

French colonial troops |

While the lion’s share of the “Indochinese” were Vietnamese, Cambodians also made up one battalion. While the transformative and emotional experiences of the soldier (linh tho)-workers in France has been the subject of at least one dedicated study in English (Hill, 2006; 2011a; 2011b), I am equally concerned with the objective experience of the Indochinese en route to the battlefields, their wartime actions, and intellectual responses. A horrible war by any standards, it was not surprising that many thousands of Vietnamese and Cambodians made the supreme sacrifice, or died for France (“mort pour la France)” as written on the epitaphs of those buried in France. I am also concerned to link Indochinese participation in the war with the “anti-war”and/or anti-colonial movement in Paris and in Indochina.

In sequence, the article seeks; first, to examine labor and military recruitment at the source, including the special roles of the royal courts; second, to assess the role played by the Indochinese infantry battalions pressed into the trenches in the Somme as well as in the Balkans; third, to expose the contradictions posed by France’s patriotic appeal for “volunteers” versus the anti-colonial movement at home and in the colonies; and, finally, to examine the juncture between the émigré worker-soldiers in France and the activities of the burgeoning socialist and communist underground in Paris and, back hone, as best exemplified by the activities and writings of Ho Chi Minh including the now-famous petition he presented on June 18, 1919 at the Versailles Peace Conference, the international gathering that literally bookended the war.

In particular I have examined little known Journal de Marche et Opérations documents, in turn sourced to the French Service Historique de la Défense (SHD), Départment de l’armée de Terre, to offer details on the journey of the conscripts to France, as well as their labor and frontline deployment in France and, in one case, in the Balkans. Taking the form of a diary, it is possible to track each of the battalions from their date of departure, arrival, deployment, service, and date of disbandment. Indispensable as possibly the only extant battalion-level documents relating to the actual work-combat experience of the Indochinese, the journals are nevertheless uneven in composition, and lacking in mobilization-demobilization details, evasive on casualty rates, and suffering from over-generalization. Written by French battalion commanders, the subaltern character of the Indochinese can be taken for granted, just as their voices are missing.

General Mobilization in Indochina/War Economy

Up until the outbreak of the “Great War” (1914-18), the total number of Indochinese immigrants in France scarcely exceeded several hundred. But as France turned to its colonial empire to defend itself in the wider war with Germany both at home and in the Balkans, the wave of Vietnamese soldier-workers arriving in France spiked in the 1915-1919 period to a figure of 42,922 tirailleurs (rifle company or infantry) and 49,180 workers (Brocheux 2012). They comprised together 15 infantry battalions and logistics formations. Among the latter were 9,019 male nurses and 5,339 clerical and administrative workers. Additionally, there were 48,981 civilian workers divided between specialists and non-specialists assigned to 129 metropolitan establishments. By origin, the 93,411 worker-soldier (practically all male) hailed from, respectively, Tonkin or northern Vietnam with some 24 percent, Annam or central Vietnam, 32 percent, and with Cochinchina or southern Vietnam and Cambodia with around 22 percent share (Rives 2013). The wartime experience of the Indochinese might be compared to that of the Chinese recruited by France and Great Britain, 140,000 in all, almost exclusively pressed into labor and logistics work (Calvo and Bao 2015). As explained below, the Vietnamese experience in France more closely resembled that of the can contingents.

The mechanized war that bled the industrialized nations of their physical resources in the production of munitions and weapons of destruction was no less a war for resources calling upon global – read imperial – supply networks to feed metropolitan industry and to succor its armies. As with the British empire, so the French looked upon its colonies for these resources. Notably, on August 8, 1914, Paris banned all exports of cereals and cattle from Indochina with the exception of markets in France, England, the Netherlands Indies, Japan, Russia and other French or Allied colonies (ANC 15765 Correspondances concernant la guerre…1914-18, Gouverneur Général Indochine, Aug. 8, 1914). In other words, trade with Allies was sanctioned while trade with the German enemy was foreclosed

In an order of November 6, 1914, repeated March 28, 1915, the French military in Indochina prepared for a general mobilization. Simultaneously, a “state of siege” was declared in Cochinchina, administered directly as a colony, and in Tonkin, a de facto colonial setup. Orders went out from the Ministry of War to register all French males in residence in Cochinchina as well as in Cambodia, then a French protectorate, with a view to mobilization. This was accomplished with respect to those employed in government services according to department. Certain groups fell through the cracks but were still liable for conscription. As of September 18, 1914, all reservists and French citizens up to the age of 46 were called up. Alongside the regulatory character of the mobilization, the patriotism of the French was also called upon. There is no evidence of anti-war opposition on the part of French in Indochina and, as with metropolitan French, most were initially stirred by patriotism.

It should be understood that, having invaded Vietnam in stages, France also began to raise loyalist battalions serving as auxiliaries in a version of colonial divide and rule against ongoing rebellions. This held not only in Vietnam, but also in Cambodia and Laos, especially when it came to “pacifying” ethnic minority rebels and other “bandit” gangs. . From May 1900, Vietnamese auxiliaries also served with French forces in the Boxer Rebellion in China, including Vietnamese sailors in service with the French navy (five warships). Not all returned home alive. The graves of 20 Vietnamese sailors killed in the Boxer Rebellion alongside French officers remain in one of Nagasaki’s international cemeteries.

|

Vietnamese grave from Boxer Rebellion in China, 1900. Nagasaki cemetery (photo credit Geoffrey Gunn) |

Mobilization of Indigenous Populations

Alongside the mobilization of French citizens, the colonial administration also sought to tap reserves of indigenous manpower, including reservists. Besides outright conscription winning over the native population in Indochina was carried out on a number of levels, from persuasion, to inducements, to deception. Contemporary (?) official Vietnamese histories are unambiguous in asserting the forced nature of wartime recruitment of soldier-workers, facts repeated in a number of international histories (e.g. Marr 1971, 229-30). Kimloan Hill (2011a, 55) by contrast has argued that most recruits volunteered, noting only isolated incidents in which individuals were coerced “not a general narrative of mass conscription.” She thus falls in line with the general argument made by French military historian Colonel Rives who highlights the attraction of metropolitan France for the Indochinese in search of adventure as well as new skills. As evidence of pull factors, Hill mentions that the Imperial Court of Hue offered 200 francs to each volunteer who passed a physical examination. Other inducements included bonuses, family allowances, and – important – exemption from the compulsory and despised body tax. The recruits also received a base pay of 0.75 francs a day, rising with seniority. As she claims, a package arrangement including bonuses, wages, pensions and family allowances is simply not consistent with out-and-out conscription (Hill 2006, 259), although this detail might be questioned.

In the absence of village-level documentation this conundrum is difficult to answer. First, we must acknowledge the role of the royal houses along with pro-French mandarins in the recruitment of, respectively, natives of Cambodia and those coming under the jurisdiction of the Court of Hue in Annam, both “protectorates” in the French Indochina set-up. We must also acknowledge government control over information and pro-France-anti-German propaganda. Recruitment posters promised prosperity and racial equality. According to military historian Rives (2013), to facilitate recruitment, propaganda films playing up the lavish lifestyle of the volunteers in France were shown at the village level. Posters appeared in all the major towns offering an image of a sharpshooter pointing out to a crouched peasant all the material benefits of recruitment.

Hill (2006) also allows for push factors favoring recruitment as with hardships stemming from the floods of 1913-15 in northern Vietnam, along with drought and rural banditry in central Vietnam and here I am in agreement. For the indigent landless Vietnamese, especially from the overcrowded northern delta and the marginal and poverty-stricken central Vietnam coastal region, there was every reason to move out, just as future generations would be lured into the mining camps of Laos and northern Vietnam, or as plantation labor in the south or even overseas, more often than not in deplorable conditions and with high mortality. But all labor recruitment in colonial Vietnam was a mix of inducements and pressure and, as I argued above, we can expect that wartime labor recruitment was no exception. Undoubtedly, to use the expression of Tobias Rettig (2005), these were “contested loyalties.”

Cambodian Princes

In Cambodia, the patriotism of the royal family was used to induce the conscription of their unlettered subjects or country cousins. With the permission of King Sisowath Monivong (r.1904-27), seven royal princes were inducted into the 20th Bataillon de Tirailleurs Indochinois (BTI) for service in France, three of them actively recruited by the king. The princes were granted special allowances, as with subventions to provide for their families in their absence. King Sisowath himself signed off on a royal ordinance declaiming the “voluntary” action of the princes in joining the 20th Battalion “for the war in France” (ANC 10421 “Princes éngagés au 20 Bataillon Indochinois, Oct. 28, 1916). In fact, such members of the royal family as crown prince Sisowath Monivong, a graduate of the Saint-Maixent military academy and a second lieutenant in the Foreign Legion, actively engaged in the recruitment of Cambodians for the World War I effort.

Undoubtedly, in a protectorate of highly restricted literacy matched by information control, recruitment of Cambodians for the “war in France” proceeded more easily with the royal volunteers stepping into the breech. At the moment of their departure for France from Saigon, the Cambodian volunteers were offered a “spectacular” official salute. Practically, the first Cambodians to set foot on a ship, much less leave their natal provinces, their lives would never be quite the same again.

Certain Indochinese who had been students in France or Algeria were inducted directly into metropolitan units as subjects of France and only subsequently admitted to the BTI. Among them were the Cambodian princes Pinoret and Watchayavong along with the Vietnamese, Nguyên Ba Luan. They were joined by students from trade and professional schools in Aix-en-Provence and Angers (Rives 2013).

The Journey

Depending upon place of recruitment, as revealed in Journal de Marche documents, the soldier-worker battalions departed from Haiphong, Danang, and Saigon, variously north, central and southern Vietnam.

|

Vietnamese soldiers enter St. Raphael |

Dubbed “Indochinese,” especially as “Vietnamese” did not enter French vocabulary until after the August Revolution of 1945, the French were also careful to maintain the cohesion of these regionally recruited battalions. Ships departing from northern ports invariably staged at Saigon before embarking upon the long journey to France. Typically the ships would bunker at Singapore, Penang in some cases, Colombo, Aden, Suez, and one or two Mediterranean ports prior to arrival in Marseilles. One variation was a stage at Diego Suarez on Madagascar. Another was at Djibouti. Nevertheless, there were a number of variations upon the typical six week passage, either delayed departure or circumstances en route.

Shipboard conditions, in the words of one analyst, were the first “disillusionment” experienced by the travelers (Hill 2011a: 55). This is not only a reference to overcrowded conditions and poor food (at least one contingent rioted over this question even prior to departure in Haiphong) but illness and death. The case of the 13th Battalion, raised in northern Vietnam is illustrative. Departing Haiphong on March 29, 1916 on the SS Amazone, an outbreak of cholera forced a disembarkation and the quarantining of the battalion in Saigon. Obliged to continue their journey aboard the SS Pai Ho, the 13th Battalion, numbering 1,023, were accommodated alongside 1,044 workers in atrocious conditions.

No sooner had the vessel departed Saigon/Vung Tau for the long voyage to Marseilles than health problems were encountered, especially stemming from overcrowding. Arriving in Marseilles on July 9, the total deaths from cholera and beri beri since departure numbered 129, a terrible attrition by any count. Besides “disillusionment,” the French also detected serious “demoralization” among the soldier-workers (SHD 26 N 874/12 Journal de Marches et Operations de 13th Bataillon de Tirailleurs). Adding to the risk, certain ships were also torpedoed (Hill 2006: 260).

First Combat

According to Rives (2013), the first Indochinese to see conflict in the war were crew members of the Mousquet, part of a French naval group which, on October 29, 1914, squared off against the German cruiser Emdem in the Malacca Straits. The three Vietnamese who died in this sea battle can thus be counted as the first victims of the Great War from Indochina. In January 1915, the Minister of Colonies, Gaston Doumergue, wrote to his colleague (Minister of War) Alexandre Millerand that “the loyalty of the subjects of the Union would be strengthened if we admit [them] to compete for military operations currently being conducted.” As a first step, Paris demanded the dispatch of Vietnamese mechanics and lacquer workers to treat the wings of airplanes, with the first arriving in Pau on March 28, 1915 (Rives 2013). The French high command then requested the dispatch of 35-40,000 men. Accordingly, on October 7, 1915 Paris authorized the participation of “Indochinese” military formations in the conflict. By that stage, 4,631 indigenous workers had already been sent to France. Governor General Ernest Roume (April 1915-May 1916) then authorized the departure of the first two battalions made up of career elements. On October, 21, 213 infantrymen of the 1st BTI boarded the SS Magellan, bound for France; the remainder following on the Mossoul (Rives 2013). Still, it would not be until early 1916 before the Indochinese battalions actually arrived in France, entering the war at a crucial stage. While avoiding certain of the earlier murderous trench warfare episodes on the Western front – although not entirely – they also bore the full brunt of German aerial bombing as it became more refined.

Worker or Service Troops

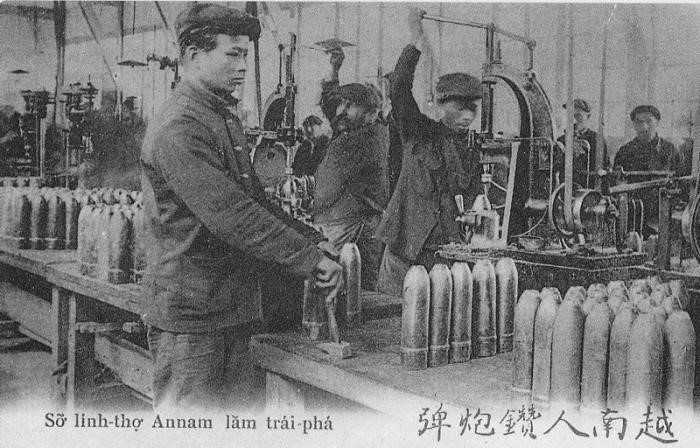

Indochina was generally considered by the French General Staff as primarily a reservoir of labor as opposed to a source of combatants. Accordingly, the great majority of the Indochinese battalions (bataillons d’étapes), 15 in all, comprised Service Troops. Certain battalions were pressed into difficult and unsafe employment as in gunpowder and munitions factories. As Rives (2013) explains, viewed as by the French as more docile than European workers, the Indochinese were used as “guinea pigs” in the Taylor system established in these institutions. On the other hand, French unionists considered them unworthy to be full-fledged workers because they refused to go on strike and willingly worked overtime to collect premiums. For instance, in the Bergerac munitions plant, they contributed 70 percent of production while representing only 50 percent of the workforce. They also proved to be skilled mechanics in both the aviation plants and railway workshops (Rives 2013).

As revealed by the Journal des Marches, the workers entered separate camps pending assignment to a variety of government departments such as forestry, agriculture, public works and, especially, munitions factories.

|

Vietnamese munitions workers |

Many of these work detachments were outside the war zone. Still others were given specialist training as drivers or as telephone operators. In fact, large numbers of workers served as railroad workers building or repairing vital rail or road links in the war zone. Other Service Units maintained lines of communication, such as with the 3rd and 9th Companies of the 9th BTI transformed into the 53rd and 54th Batteries, charged with building railway lines. Surviving postcards, such as published in Rives and Deroo (1999), offer graphic images of Vietnamese soldier workers arriving in Marseilles, staging at parade grounds, under instruction, at work, being conveyed to the front, and even deployed in the trenches.

For example, the 1266-strong 14th Battalion, raised in Tonkin, and arriving in Marseilles on October 5, 1915, spent most of the war (until December 16, 1917) employed in the Poudrerie Nationale de Saint-Médard, or gunpowder works located near Bordeaux (Journal de March 26N 874 14). An establishment dating back to the reign of Louis XIV, the atmosphere was intimidating and the health risks high. Short on detail, the incidence of hospitalization nevertheless appears high in the banal official account, while other evidence suggests that powder and munitions plants were operated under the most deleterious work conditions. Whatever else, the transition from farm to factory was telescoped for these peasant-workers. But it is also true that the instant making of a Vietnamese proletariat in France may also have been temporary as industrial development back home was deliberately choked to favor metropolitan business interests. And so, when it came to demobilization, as discussed below, very few continued in factory labor in Vietnam, and none in Cambodia.

Still, others learned new skills. In 1917, the BTI deployed 5,000 men in the automobile service. Having learned to drive in less than a week, these sections played a major role in bringing military supplies to the front. In Spring 1918, drivers of the No. 1 Automobile Reserve, two thirds of whom were Indochinese, relayed emergency reinforcements to the front. Some drivers came under artillery fire or were engaged by enemy infantry in combat. They sometimes come in contact with their Thai counterparts (Rives 2013).

Some Indochinese doctors also volunteered their service. Thus, the 10th BTI, served the Hospital Saint-Louis de Marseille, while the Caudéran near Bordeaux hosted a number of Vietnamese practitioners. Notably, from June 1916, Dr. Thai Van Du was assigned to Marseille hospital 224. Nurses, numbering 9,000, received only minimal training. The majority of them were deployed in the rear while others served as stretcher bearers on the battlefield. At least two received citations. On several occasions, the companies attached to the 21st BTI collected the wounded. Several Vietnamese also became pilots, among them, Captain Do Huu Vi, along with Phan Tao That and Cao Dac Minh. Notably, Corporal Xuan Nha of A 253 Squadron was shot down in 1917 by four enemy aircraft (Rives 2013).

The Battlefronts

As revealed by Journal de Marche documents, of the 23 battalions formed from Indochina, the majority arrived in the port of Marseilles. Typically, they immediately proceeded by rail to Saint Raphael camp near Fréjus in southeastern France where they trained and were prepared pending immediate dispatch to the front in the case of the rifle companies. A small number of battalions were actually formed at Fréjus from among arriving rifle company units.

But certain among the Service troops also experienced considerable risk including death. The experience of the 16th BTI might be taken as an example. Formed on January 19, 1916 at Hue in central Vietnam, the 1,000-strong battalion embarked from Danang on May 30 “to take part in the campaign against the “Austro-Hungarians.” Touted in official correspondence as a “purely volunteer” force, the battalion disembarked at Marseilles on July 18, pending relocation to the Saint Raphael-Fréjus camp. Reinforced by new arrivals who had staged in Madagascar, within two months the combined battalion was dispatched to Froissy, a station terminus on the vital supply rail link paralleling the Somme canal on the Western Front. Notably, the 16th BTI were tasked to supply artillery positions with shells. On April 11, 1917, they were caught in a bombing raid at the Froissy station, with three killed and five more were killed the following year. Initially assigned labor and guard duties at Froissy, and subsequently supplying artillery munitions to the front, within days of arrival on September 20, the battalion came under intense aerial attack, a new innovation in the age of mechanized warfare. Even so, the first major casualties were only recorded on December 11 with three Vietnamese killed and eight wounded. Through to September 1918 sections of the battalion labored on the Somme-Bionne rail line, others on labor duty, still others as telephone operators. None of the 16th Battalion appears to have been pressed into front line combat or exposed to trench warfare. Eventually, on June 6, 1919, the infantrymen (1,074 minus fallen comrades) shipped out of Marseilles for the home journey. Devoid of context, the Journal de Marche description masks the horrors of war on the Western Front.

The Combat Battalions

The experience of the 7th (Tonkinese Rifle) Battalion was entirely various. Formally created on February 16, 1916 at Sept Pagodes, a river town in Hai Duong province in the mid-Red River delta of northern Vietnam – the major source of conscript labor for mines and plantations both inside Vietnam and in the colonies – the 1,000 strong “volunteers” battalion sailed for Marseilles on October 5. Once in France the battalion made an obligatory stage at the Fréjus boot camp, prior to leaving direct for the Western Front on April 4, 1917. Within 10 days they were in place poised to launch attacks on German positions, literally to kill or to be killed. According to an internal French military memorandum, from May 27, until July 30, 1917, the 7th Battalion deployed at Linge in the Vosges sector successfully held their ground. As the report noted, “Great satisfaction in the manner in which they comported themselves both from the point of view of attitude towards the enemy and point of view of discipline” (Journal de March 26N 87/4/5). The Journal de Marche offers no details but Linge in the Vosges mountains in Alsace on the France-German border, was the site of trench warfare reaching murderous intensity in 1915 with both sides squared off at close proximity across a labyrinth of trenches and stone strong points.

Notoriously the war of attrition in the World War I trenches and battlefields brought about a great sense of unease in France. Social unrest was on the rise as a result of both the length and the brutality of the war (Duiker 2000, 54). In December 1915, antiwar protests even reached the French parliament. By 1917, heavy loss of life and economic crisis led to defections of French soldiers along with worker strikes, injecting an element of contention into the conduct of the war. While it remains unclear if the Vietnamese actively participated in the military mutinies discussed below, they began to participate in the labor movement (Hill 2006, 274-75).

Entering a long stalemate in 1917-18, the balance on the Western Front only began to shift with the entry of American forces following the American declaration of war against Germany on April 6, 1917. Certain Indochinese battalions would come under the wing of the Americans, as with the 12th Battalion formed in February 1916 in northern Vietnam. Facing down enemy bombardments at Chalons sur Marne (Champagne) in March 1918, where they labored on a railway line, the 1st Company earned a special citation for bravery. Meantime, the 2nd Company was placed at the disposal of the Franco-American Mission, including building the American hospital and, on August 10, 1918, joining the Génie Americain engineering brigade in rail work at Nevers in the Loire valley down until the end of hostilities.

The Balkans Campaign

In October 1915 a combined Franco-British force landed at Salonika (Thessalonika), present-day Greece to defend Serbia against Austro-Hungarian invasion as well as prevent Bulgarian aggression. Part of a broader Balkan war, the conflict pitted the French, British, Italians and Russians against the Austro-Hungarian enemy, backed by Germany and Bulgaria. Romania entered the war on the side of the Allies in 1915 and Greece in 1917. From late 1916, the Indochinese 1st Battalion would join the French expeditionary forces alongside other colonial forces as with those drawn from Senegal and Madagascar.

Some writers such as Dutton (1979, 97), have tried to explain the paradox of the French position in operating on two fronts, the vital Western Front versus the Balkans, where military activity was limited and with the campaign enduring over three long years, even when the Germans were in striking distance of Paris. As Dutton found, this was small solace for the participants or victims. French enthusiasm for the “largely abortive” Macedonian campaign – only triumphant in the last stages of the war – actually turned upon the vicissitudes of French domestic politics and parliamentary debates rather than strict military contingencies.

Two of the four Indochinese combat battalions were sent direct to the broad Balkans theater. One was the 10th Bataillon de Tirailleurs (Tonkin Rifles) which left Hongay port on the Gulf of Tonkin on July 14, 1916, and staged at Varna on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast on October 15, 1916 en route to Constantinople. Unfortunately, this campaign is not well documented. The other was the 902-strong 1st Indochinese (Tonkin Rifles) Battalion, whose exploits I will describe in some detail, especially as standard accounts of the Vietnamese in World War I have ignored the Balkans episode, just as their historic role has tended to be folded into French military exploits.

Raised in Bac Ninh in the impoverished and overcrowded lower Red River delta, the 1st Indochinese (Tonkin Rifles) Battalion embarked Haiphong on January 17, 1916. Staging in Djibouti, they were divided into four companies each comprising some 226 infantrymen. Additionally, a group of 32 formed a machine gun section. On April 28, they embarked Djibouti with the goal of joining the Armée Français d’Orient (French Eastern Army). On May 6 they arrived in the British bastion of Salonika.

Initially charged with static “guard and defense” duties in and around the Salonika camps, they were subsequently deployed with a view to securing the road connecting with Monastir (Bitola) in south Serbia, deemed a key strategic corridor in the campaign. From August 3, 1916, the 1st Indochinese battalion began to enter the Macedonian theater joining Senegalese and Malagasy forces already in place. Between August-September 1916, they began to deploy in the lower Vardar River area in Macedonia, staging at Kozani (northern Greece) between January-June 1917, inter alia, protecting convoys, guarding trains, marketplaces, , and prisoners, such as at Trikali-Kalabaka (southwest of Thessalonika) (July 1917). On August 30, 1917, they suffered the first casualty following an enemy bombing of a railway station (Journal de March 26 N 874/1).

The disposition of the forces changed on September 17, 1917 with the battalion placed at the command of the French Eastern Army. They were then redeployed into mountainous southwest Macedonia and adjacent areas in Albania, specifically around Lake Ochrida (Ohrid), prior to entering the battlefront. Notably, on October 14, the 4th Company coming under enemy grenade and aerial attacks lost one rifleman, with one wounded, and 12 “disappeared.” On the offensive at Pogradac (southeast Albania) on October 19, 1917, they also took casualties (with five infantrymen killed, and another 15 wounded). “The offensive continued” with the battalion occupying the heights of Lake Ochrida and controlling the road to Pogradac. On October 22, 1917 under constant pressure and taking losses, owing to “extreme fatigue” the 4th company was relieved by the 1st company. Coming under a massive enemy attack, they took more casualties from grenade attacks, suggesting close range fighting. Constantly bivouacking through this campaign, on October 25 both companies were withdrawn from active combat to focus upon road building activities, and with the roads also becoming targets of enemy bombing (Journal de March 26 N 874/1). Although seasonal or health conditions are not mentioned in the Journal de Marche account, we may assume that this was also a tactical retreat made necessary by a punishing winter with snow covering the higher elevations and peaks.

In early July 1918, the campaign entered a new phase with the Battalion now engaging offensive actions against Austrian positions. On July 10, a reconnaissance of Austrian positions revealed that the enemy had withdrawn in the direction of Bulgaria (Journal de March 26 N 874/1). The general enemy retreat in Albania was actually confirmed by the New York Times under such banner headlines as, “Foe Forced from Tomonica Valley and Austrian Attacks Fail: Bulgars also Menaced,” and “Vienna admits retreat in Albania” (New York Times, July 10-11, 1918).

Still, that was not the end of the war. Meantime, the second and third companies took up front line positions in the vicinity of Porocani (Albania), at high elevation. On July 31, 1918, the first companies faced down a “violent Austrian attack” on the Porocani front. At the cost of one casualty, they successfully repulsed the Austrian force and maintained their ground. But in August 1918, the battalion also began to take casualties in the form of “violent bombardments” by Austrian forces. “Violently attacked,” the first and third companies held fast At this time (August 25), a retreat by the Italians in the Tomorica and Devoli valleys weakened French lines (Journal de March 26 N 874/1). But the Bulgarians were also crumbling (New York Times, July 11, 1918).

While this brief account elides the broader geopolitical issues at play in the Balkans, by October 31, 1918, French and Italian forces had expelled the Austro-Hungarian Army from Albania. At war’s end (the Armistice went into effect on November 11, 1918), having endured two winters in the course of this punishing campaign, the brigade returned to Salonika, arriving on January 11, 1919. Now assigned to various logistics duties, the 1st Battalion staged at Fiume (present-day Croatia), Zagreb, and Belgrade, before departing on March 25 for France and home (Journal de March 26 N 874/1). To the extent that the French Eastern Army facilitated an ultimate Serbian victory, then the Indochinese battalion undoubtedly played its part, holding the line against the Austrians and pushing back the Bulgarians.

In this theater, according to Rives (2011), figures also corresponding to my reading, 23 infantrymen were killed, 41 wounded, with 10 missing. Among them would have been the loss of one rifleman and five wounded as the result of a grenade accident on June 10, 1918 (Journal de March 26 N 874/1). The sparse and terse Journal de Marche report offers no accolades, just as the heroics of the 1st Battalion were forgotten.

No overall casualty figures for the Indochinese in World War I service are offered in the Journal de Marches. But compared to France (with a 30 percent casualty rate) and other belligerents, the Indochinese battalions undoubtedly suffered less. Yet morale can never have been far from French thinking and doubtless the risk of defection outweighed the benefit of pushing colonial forces to the limit (although that also happened as well). According to Blanc (2005, 1160), it is impossible to say with accuracy how many were killed, although many war cemeteries around Marseilles offer eloquent testimony to the attrition of lives, workers included.

Nationalist Response to Wartime Conscription

Of the latter Nguyen dynasty emperors of Vietnam, one stands out in modern Vietnamese history today for his patriotism, namely the boy-king Duy Tan, born on August 14, 1899 to Emperor Thanh Thai (r.1889-1907) as Prince Nguyen Vinh San. In this narrative, as Vietnamese historian Nguyen Khac Vien (1975, 12-17; 22-25) embellishes, with his father removed from office ostensibly for insanity, the prince took his place on the Golden Dragon Throne in 1907 at the age of 7, assuming the reign name Duy Tan, or “friend of reforms.” Chosen for his youth, naivete, and pliability, Duy Tan (r.1907-16), however, proved to be as obstinate as his father before him. Ostensibly Francophile, the young king nevertheless called for a revision of the 1884 Protectorate Treaty. Against the background of local indignation at conscription for France’s wars in Europe, Duy Tan acting on the counsel of “patriot mandarins,” notably, Thai Phien and Tran Cao Van, organized a revolt on behalf of troops about to be sent to France. Timed for May 3, 1916, the plot was discovered, the French disarmed the soldiers, and Duy Tan was detained, dethroned, and exiled, joining his father in the French Indian Ocean colony of La Réunion. The two concerned mandarins were executed amidst a wave of repression.

It is of no small interest that, on May 3, 1917, the 16th BTI battalion which, as mentioned, took casualties on the Froissy-Somme front, was visited by a high ranking northern Vietnamese mandarin or imperial delegate, both talking up the kingdom of Annam and the cause of France against the “barbarians.” Commended in French dispatches for making a good impression on the troops, the mandarin also suggested a distribution of croix de guerre to the Vietnamese heroes of the bombardment. As the French military authority commented upon events back in Hue, the battalion was the first to be created in the wake of the deposition of the boy-king Duy Tan, exiled to Réunion, for “treachery” (actually, for falling in with the anti-French party). Duy Tan’s successor, as the imperial delegate observed, had swung the authority of the court and mandarins in support of the French cause. Notwithstanding the solicitations of the revolutionary party, as with distributing arms days before the events in question – the defection of the boy-king – the tirailleurs were to be commended for not participating in any anti-dynastic or anti-French movement, thus confirming their patriotism. Hence, in this narrative, the exemplary discipline of the battalion in facing down the enemy bombing was to be especially commended. This of course was pure cant. Obviously, if the emperor defected from the French cause, then the game of winning over the masses to voluntary conscription was a charade. The model the French respected, as explained, was that of the King of Cambodia who even rallied his own family. But French morale was also low. In May 1917, French veterans of the Battle of Verdun, mutinied, just as France lost more casualties relative to its population than any other power on the side of the Allies.

The 1916 Cambodian Revolt

In 1916, a revolt dubbed by the French the 1916 affair brought tens of thousands of peasants to Phnom Penh to petition King Sisowath for a reduction in taxes. Since 1912 a large-scale road-building program had been launched involving the mobilization of considerable numbers of corvée laborers. As Forest (1980: 67) points out, such conscription was poorly received by the peasantry. At the epicenter of the rebellion in Kampong Cham, some 100,000 peasants rose up prior to a march upon on the capital. Official opinion was divided as to the cause of the rebellion, whether a purely domestic affair stemming from discontent with the tax system along with official abuse, or as being manipulated by external actors. As Tully (2005, 96-99) summarizes, resentment at military recruitment for France’s war in Europe along with long standing resentment over rising tax and corvée requirements contrived to push ordinary people to rebellion. The event ended tragically with the “autocratic” Resident Superior Baudoin ordering a violent crackdown leading to the death of an indeterminate numbers of protesters.

In Cambodia, the war also opened a breach between contending members of the royal family. On one of his trips to Europe in August-September 1900, Prince Norodom Yukanthor (1860-1934), heir presumptive to the Cambodian throne, criticized French rule in Cambodia (Osborne 1969: 244-5). Having been exiled from Cambodia for “acts of disobedience,” Yukanthor then based himself in Thailand after having created an opposition movement. According to an official French source, Yukanthor was also involved in secret acts against the Protectorate and the royal government during World War I (AOM Indo NF/48/585), code for dalliance with the Germans.

Vietnamese Nationalist Response

The notion that making contacts with France’s enemy might help the anti-colonial cause was not lost upon certain Vietnamese nationalists. Confucian scholar and leader of the Look East movement (to Japan), Phan Boi Chau was one. First making contact with potentially sympathetic German consular officials in Hong Kong in 1906, again in 1910 he looked to Berlin for sources of funding for his activities (Marr 1971, 127; 151). He may also have influenced Prince Cuong De, a renegade scion of the royal family of Hue and a follower of Chau who visited Germany in 1913 more or less banking upon a German victory (Tran My-Van 2005, 97).

Other nationalists, such as Nguyen Thuong Hien, appealed in print for his countrymen to refuse conscription. He also received seed money from the German and Austrian consulates in Bangkok in support of armed rebellions against French border posts, although easily quashed by the French. Nevertheless, the numerous revolts and coups inside Vietnam continuing through World War I demonstrated (Marr 1971, 228-29) a lack of support for France in its war with Germany.

Political Backlash

We should not ignore the radicalization process experienced by sections of the worker-soldiers in metropolitan France. It is notable that the majority of the immigrants arriving in 1915 were illiterate (23,234 out of 34,715). But, as Brocheux (2012) points out, the literates would emerge as the proponents of the independence movement alongside such auxiliaries as those serving communication networks (restaurateurs), liaison persons, and propagandists (sailors, workers, house boys, and sometimes, soldiers).

Arriving in Paris from London in late 1919, where he may well have been awaiting the end of conscription for France’s war (Duiker 2000, 54), the young Ho Chi Minh registered opposition to conscription in his first extant writings. Appearing in the French Socialist Party newspaper, L’Humanité, published in Paris on November 4, 1920 under the signature, Nguyen Ai Quoc, he wrote, “We oppose sending Annamese soldiers to Syria. We must make the highest authorities understand that many of our ill-fated oriental brothers were killed in battles between 1914 and 1918 during a war for “culture and justice.” ‘Why, then, do we not have culture and justice?'” (cited in Borton 2010, 38). As Ho Chi Minh decisively shifted his allegiance away from the Second International to the Third International Congress, especially around the colonial question, he also came to rationalize World War I as an “imperialist war,” with colonial rivalry as one of its causes (Ho Chi Minh, La Vie Ouvrière, Sept. 7, 1923 cited in Fall 1967, 34).

|

Ho Chi Minh addresses Tours Conference |

From London, Ho Chi Minh had been in letter contact with another Vietnamese who made the voyage to France during the war years. This was Phan Chu Trinh (1872-1926), also known as Phan Chau Trinh, a pioneer nationalist alongside Phan Boi Chau in seeking an end to France’s occupation. Calling for the abolition of the monarchy and its replacement with a democratic republic, he then went to Japan with Phan Boi Chau. Back in Vietnam in 1907, after peasant tax revolts erupted in 1908, he was arrested. Sentenced to death, but commuted to life imprisonment, in 1911 he was pardoned and deported to France. From Paris in 1915, he sought to win the support of progressive French politicians and Vietnamese exiles. According to Vinh Sinh, (2009: xiii), when Germany attacked France, Chau refused to be conscripted for French military service. He was duly arrested and spent 10 months in Santé prison in Paris (September 1914-July 1915) on suspicion of asking Germany for help to fight against France. Phan Chau Trinh, radical lawyer Phan Van Truong, and Ho Chi Minh (Nguyen Ai Quoc) jointly drafted the set of demands presented by Ho on June 18, 1919 at the Versailles Peace Conference. These included a complete amnesty for Indochinese political prisoners, and reform of the justice system (Vinh Sinh 2009, xvii).

We should not ignore as well the presence in Paris in the 1919-1921 period of such key figures in Chinese communism as Deng Xiaoping, Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, and Li Lisan alongside some 1,500 Chinese work-study students many deeply touched by international events and left-wing politics (Bailey 1988: 442). But if we compare the Vietnamese with the Chinese national experience, as discussed by Calvo and Bao (2015), then we would have to say that Vietnam had no equivalent to China’s May 4th Movement arising out of failure to secure any gains at Versailles. To be sure, Prince Cuong-De sought to make capital from the event by writing a missive of February 12, 1919 to US President Wilson. As Cuong-De’s biographer Tran My-Van (2005: 102) writes, while the French authorities took serious note of the exiled Prince’s actions, at the same time they were able to dismiss Ho Chi Minh’s petition as mere “libel.” In any case, departing the scene for Moscow, the future Vietnamese leader literally remained out of the picture for the next fifteen years, and with the Tokyo-based Cuong-De increasingly beholden to Japanese patrons and remote from the mainstream of Vietnamese nationalist politics

The Paris-Based Foyer Indochinois

The end of the war and the demobilization of workers only signaled a new problem for the French authorities, namely one of community control, especially as the numbers of Vietnamese resident in France grew, along with their political engagements. As Duiker (2000, 56) remarks, of the 50,000 odd Vietnamese remaining in France at the end of the war, a few hundred had arrived to study, mainly the children of wealthy families. They entered a highly politicized atmosphere.

The authorities looked to guide these individuals not only towards French culture but away from subversive activities. The authorities closely monitored student and other Vietnamese circles throughout France. The dossiers are huge just as the spying and surveillance exercise must have consumed considerable resources and ingenuity. But on November 26, 1920, with the approval of the minister of colonies and with the special support of the minister of interior and former governor general of Indochina, Albert Sarraut, the authorities pressed ahead with the creation of an Association Mutuelle de Indochine also dubbed the Foyer Indochinois. Furnished with premises at 15 Rue de Sommerand, vested with an annual subvention of 50,000 francs, and under the directorship of a former Vietnamese member of the colonial council, the medical doctor, Le Quan, the Foyer went about its professed mission of socializing its members into French culture, doling out social welfare assistance, and keeping up links with their homeland (AOM SLOTFOM III 40 “Association Mutuelle de Indochine”).

By 1926, however, as a newer generation of Vietnamese arrived in Paris, the conservative leadership of the Foyer dominated by the “constitutionalists” (the Parti Constitutionalist Indochinois which attracted a student membership), came under challenge. By this juncture, Vietnamese organizations active in Paris also included the Annam Independence Party, the Annamite Union, and the Association of Annamite Workers (active in Le Havre). On February 26, 1926, on the occasion of a leadership ballot, “violent” scenes emerged with members of the “bloc de progressistes,” shouting nationalistic and communist slogans, including the words “Vive l’independence de l’Indochine.” In elections on May 2, the constitutionalists lost ground to the progressive bloc. In elections on October 31 the progressives strengthened their hand winning 110 votes out of 130. This success was made possible through the recruitment of a new membership largely comprising Vietnamese cooks working in Paris. Behind them stood former Nguyen Ai Quoc associate Nguyen The Truyen, founder of the Annam Independence Party and editor of three left-wing newspapers, Viet-Nam-Hoc; Phuoc-Quoc and l’Ame Annamite. Nguyen The Truyen was also the force behind an Association des Travailleurs Manuelle (or manual workers’ association), which had hitherto avoided political issues. As described by a judicial inquiry into the election “fiasco,” the association comprised 150 members, for the most part “communist cooks,” members of the radical “Association des Cuisiniers,” along with Bolshevik students, led by the anti-French Vietnamese Nguyen The Truyen. As the head of the Sûreté Générale or political police then advised, “It seems that the moment has come in Indochina to suppress the liberalities accorded such groups which, one after the other, fall under the influence of the Bolsheviks.” In the meantime, he advised, the Foyer should be brought back under the control of “healthy” elements as with ex-Indochina bureaucrats outside of the “excesses” of young extremists (AOM SLOTFOM III 40 “Association Mutuelle de Indochine,” Note pour le Ministre de la Police et de la Sûreté Générale en Indochine).

At the end of 1927 Nguyen The Truyen returned to Vietnam traveling up the coast to Hue and meeting Pham Boi Chau, but breaking with the communists. Back in France during the progressive Popular Front period (1936-37), although home in Vietnam in 1938, he was arrested by the French in 1941 (Quinn-Judge 2003: 329). He was not alone and one by one other France-based intellectuals (Trotskyists and “Stalinists” alike) would return to Vietnam injecting a new dynamism into the anti-colonial movement, especially in the world of literature and political journalism which blossomed in Saigon, at least until the suppression of liberals “liberalities” became a reality by the end of the decade.

Demobilization

The demobilization of the battalions (as testified by the Journal de Marche et Opérations) progressed rapidly. As of July 1920, just 2,000 Vietnamese soldiers remained in such diverse locations as Germany, China, the Levant, Syria, Lebanon, Morocco and the Balkans. By contrast, the demobilization of the workers in France was delayed especially as they were pressed into reconstruction projects, although essentially completed by December 1920. Nevertheless, some 2,900 Vietnamese soldiers and workers gained permission to remain in France for work, study or marriage, literally the first Vietnamese “immigrants” paving the way for waves of newer arrivals. Confronting discrimination, they too organized, as with the formation of workers’ organizations. Others gravitated to French Communist Party affiliate organizations, with some, such as sailors, linking up with the underground communist movement back home. By the late 1920s France would be somewhat supplanted as a center of anti-colonial activity, especially as French police surveillance became tighter. Increasingly, Vietnamese nationalists looked to China and with Canton (Guangzhou) especially a major pole of attraction such as documented by scholars such as Marr (1971) and Duiker (2000).

In 1915 a battalion of the 3rd Regiment of Tonkinese Rifles (3rd RTT) was sent to China to garrison the French concession in Shanghai. The rifle companies remaining in Indochina saw service in 1917 in putting down a mutiny of the Garde Indigène (native gendarmerie) in Thai Nguyen province in northern Vietnam. In August 1918, three companies of the Tonkinese Rifles formed part of a battalion of French Colonial Infantry sent to Siberia as part of the Allied intervention following the Russian Revolution (Rives and Deroo 1999, 53-54). In the course of conflict, Indochinese units won 11 military medals and 333 “croix de guerre” (Rives 2013). Four regiments of Tonkinese Rifles continued in existence between the two World Wars, seeing active service in Indochina, Syria (1920-21), Morocco (1925-26) and in the frontier clashes with Thailand (1940-41) (anon., 1991).

The Soldier Returnees

As described by Rives (2013), when the Indochinese soldiers returned home, they were officially informed of their rights. In addition, by province, an Assistance Committee assumed responsibility for sending them parcels during the hostilities. Very soon, however, indifference or annoyance set in against the unruly “returnees from France” as they were called. In turn, they tended to reject the traditional authorities and sought to deal directly with the colonial administration whose language they had learned to speak. Some of them received a share of ricefields reserved for them along the Bach Ghia canal in Thai Nguyen province, while others received a bonus that allowed them to set up as an artisan or farmer. Those demobilized from Annam and Tonkin were honored with a mandarinal grade. Those from Cochinchina were given a right of precedence in ritual ceremonies. The Cambodians were decorated with royal honors (Rives 2013).

Others, however, began to pursue more activist careers. In the wake of the suppression of the Nghe Tinh peasant rebellion of 1930-31, a partly communist-inspired affair also leading to the creation of “soviets,” an official commission of inquiry collected a large number of depositions, basically, confessions from suspects (Gunn 2014, 94-95). Taking the declaration of one peasant-cultivator cum soldier returnee from France, Bui Hat, as emblematic, the judicial official asked, “Why did you join the communist party?” To which he answered. “It took me by surprise. It happened that I was forced to join the communist party.” “What is communism? he was asked, to which he replied, “I deny having been a communist. I spent several years in the military infirmary. I spent three years at Fréjus after the war” (AOM Indochine NF/334/2689 “Commission d’enquête sur les evénéments du Nord Annam,” July 9, 1931).

Ton Duc Thang

The most celebrated returnee, at least in Vietnamese communist historiography, was undoubtedly future Democratic Republic of Vietnam president Ton Duc Thang (1888-1980) who, upon return to Vietnam from France in 1920 formed the Association of Workers of the Saigon Arsenal. Setting aside disagreements over Ton’s involvement with a Saigon labor union in the 1920s and the naval-yard strike there in 1925, Giebel (2004, 13-14) questions whether he participated in a mutiny on a French ship sent to the Black Sea in 1919 to help defeat Bolsheviks. Shipping rosters and naval records reveal he was not on any of the ships on which the most decisive revolts broke out, and also did not participate in any of the core revolts on the Black Sea in 1919. Nevertheless, as Giebel (2004, 24) allows, having heard stories of the Black Sea mutinies while serving as a French conscript in Toulon, the future president was involved in the mass protests in southern France.

Postwar, the first major defection from within the colonial army ranks occurred in the northwest of Vietnam. On February 9, 1930, part of the 4th Regiment of Tonkinese Rifles stationed at Yen Bai mutinied against their French officers. Led by the major non-communist political party, the Kuomintang-modeled VNQDD or nationalist party, the Yen Bai mutiny, obviously premature, was not only doomed but the leadership collectively executed. Other rifle companies eventually defected from the French cause in the mid-1940s, lending crucial support to the then embryonic Viet Minh (Gunn 2014, 61-63). But it is another matter to suggest that their actions were a result of distantly remembered World War I experiences, especially as other rifle companies remained loyal.

It is hard to trace the career tracks of Cambodian soldier returnees, but some were in the vanguard of future social movements, especially as their loyalties were tugged by nationalists just as their eyes were opened by experiences – shipborne and in battle – that few at home could have imagined. One who did play a key future role in the development of modern Cambodian nationalism was Pach Chhoeun, a former interpreter for the troops. Another who had fought for France was Khim Tit. Joining the colonial service during the Pacific War, he took his place in the Japanese-sponsored cabinet, later becoming a governor of Kampot province. A pro-monarchist but also a pro-independence politician, he also played a cameo role at the end of the war (Kiernan 1985, 20-21).

Summing Up

From the above it is clear that there was no straight line evolution of thinking on the part of the near 100,000 Vietnamese worker-soldiers serving in France and other World War I theaters and the iniquities of imperialist war or, for that matter, even the paradox of dying for France while Vietnam remained enslaved. In fact, the majority of soldiers were cocooned from politicization and, for the survivors, doubtless glad to be alive and to receive their hard won wages and pension packages. Unlike the France-based workers, many of the rifle company battalions served outside of France. Even those who served in France were more mobile or quarantined from contact with locals. . Not so the workers who were more closely exposed to the realities of grinding munitions factory, and agricultural work and, doubtless, discrimination. Certainly, as with those exposed to the French labor movement, they were easily mobilized. Although this essay has mostly focused upon the soldier’s actual experiences, we have also noted the role of the “communist cooks” in Paris in the early postwar period. But others, especially lacquer workers employed in the aircraft industry, were also radicalized and unionized.

As revealed by the Indochina Foyer story, the real struggle for the French in both France and in Indochina, was for the hearts and minds of the young intellectuals torn between collaboration with the French project and those, as with the young Nguyen Ai Quoc/Ho Chi Minh, who understood Indochina’s predicament as one of colonial subjugation in the vice of imperialist war, and looked to international solidarity. Ultimately, the intellectuals including the France-trained returnees would galvanize the anti-colonial movement.

Denied credible prior knowledge of the horrors of the Western Front, and pumped up by false loyalty to France, plus inducements, the mostly illiterate peasants from the poverty stricken and famine-prone provinces of the Red River Delta and north-central Vietnam made ready recruits, even short of coercion. To be sure, as Brocheux (2012) has commented, France invoked the same patriotic call for men and resources during World War II. In 1939, Minister of Colonies Georges Mandel called upon 80,000 Indochinese. In June 1940 at the time of the French capitulation to Germany there were 28,000 (8,000 infantry and 20,000 unspecialized workers) on French soil.

The tombs of fallen Indochinese soldiers, such as those of the Douaumont ossuary in northeastern France and at sites in Albania, attest to sacrifices made during the Great War (Rives 2013). The same can be said of Fréjus, site of the military camp for forces arriving from Indochina, where a pagoda, an Indochina war memorial-necropolis, and a marine museum recall this link with the past but only for those “mort pour la France” or who “died for France.”

Geoffrey Gunn is emeritus professor, Nagasaki University, and visiting professor, University of Macau (2014-15). Books include, Rebellion in Laos: Peasant and Politics in a Colonial Backwater (1990); Encountering Macau: A Portuguese City-State on the Periphery of China, 1557-1999 (1996); Timor Lorosae: 500 years(1999), First Globalization: The Eurasian Exchange, 1500-1800 (2003) History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800 (2011); Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power (2014).

Recommended citation: Geoffrey Gunn, “Coercion and Co-optation of Indochinese Worker-Soldiers in World War I: Mort pour la France”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 1, No. 1, January 1, 2016.

Related articles

- Alex Calvo and Bao Qiaoni, Forgotten voices from the Great War: the Chinese Labour Corps

Bibliography

Archives

Archives Nationale du Cambodge (ANC)

Centre des archives d’Outre-mer (AOM)

Service Historique de la Défense (SHD), Départment de l’armée de Terre

Service de liaison avec les orginaires des territoires français d’Outre-mer) Fonds Ministèriel (SLOTFOM)

Ministère de la Défense. Memoires des hommes – Journaux des unités. Bataillons de tirailleurs indochinois > 7e bataillon: J.M.O. • 16 février 1916-15 mars 1919 • 26 N 874/5

References

anon. 1991. Les Troupes de Marine 1622–1984, Paris: Charles-Lavauzelle.

Bailey, Paul.1988. “The Chinese Work-Study Movement in France”, The China Quarterly, Volume 115, pp. 441-461.

Blanc, M-E. 2004. “Vietnamese in France.” in Melvin Ember, Carol R. Ember, and Ian Skoggard, eds., Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World. Vol. 2, Diaspora Communities, New York: Springer, pp. 1158–1166.

Borton, L. 2010. Ho Chi Minh: A Journey, Hanoi: The Gioi Publishers, (2nd ed.).

Brocheux, P. 2012. (September 20) “Une histoire croisée – l’immigration politique indochinoise en France, 1911-1945,” Mémoires d’Indochine, accessed December 1, 2013

Calvo, A. and Bao Qiaoni. 2015. “Forgotten voices from the Great War: the Chinese Labor Corps”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 49, No. 1, December 21.

Duiker, W.J. 2000. Ho Chi Minh, New York: Hyperion.

Dutton, D.J. 1979. “The Balkans Campaign and French War Aims in the Great War,” The English Historical Review, Vol. 94, No. 370. Jan., pp.97–113

Fall, B. 1967. ed, intro., Ho Chi Minh on Revolution: Selected Writings, 1920-66, New York: Praeger.

Forest, A. 1980. Le Cambodge et la Colonisation Française: Histoire d’une colonisation sans heurts (1897-1920), Paris: L’Harmattan.

Giebel, C. 2004. Imagined Ancestries of Vietnamese Communism: Ton Duc Thang and the Politics of History and Memory, Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Gunn, G.C. 2014. Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power, Lanham, MA. Rowman & Littlefield.

Hill, K. 2006. “Strangers in a Foreign Land: Vietnamese Soldiers and Workers in France during World War I,” in Nhung Tuyet Tran and Anthony Reid, eds., Viet Nam Borderless Histories, Madison WI, University of Wisconsin Press, pp.256-289.

_________.2011a. “Sacrifices, sex, race: Vietnamese experience in the First World War,” in Santanu Das, ed., Race, Empire and First World War Writing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.53-69.

________. 2011b. Coolies into Rebels: The Impact of World War I on French Indochina. Paris: Les Indes Savant.

Kiernan, B. 1985. How Pol Pot Came to Power: A History of Communism in Kampuchea, 1930-75, London: Verso.

Lockhart, G. 1989. Nation in Arms: The Origins of the People’s Army of Vietnam, Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Marr, D.G. 1971. Vietnamese Anti-Colonialism 1885-1925, Berkeley: University of California Press.

New York Times

Nguyen Khac Vien 1975, Nguyen Khac Vien, The Long Resistance (1858-1975), Hanoi: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Osborne, M. E. 1969. The French Presence in Cochinchina & Cambodia: Rule and Response (1859-1905), Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

____________1978. “Peasant Politics in Cambodia: The 1916 Affair,” Modern Asian Studies 12 , pp.217-243.

Quinn-Judge, S. 2003. Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years 1919-41. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rettig, T. 2005. Contested Loyalties: Vietnamese Soldiers in the Service of France, 1927-1939, Ph.D. dissertation, University of London.

Rives, M. 2013. “Les militaires indochinois en Europe (1914-1918).” Website of L’Association Nationale des Anciens et Amis de l’Indochine (ANAI) Accessed 5 March 2013.

Rives, M. and E. Deroo. 1999. Les Linh Tap: Histoire des militaires indochinois au service de la France, 1859-1960. Panazol: Lavauzelle.

Tran My-Van 2005. A Vietnamese Royal Exile in Japan’ Prince Cuong De (1882-1951), London: Routledge.

Tully, J. 2005. A Short History of Cambodia: From Empire to Survival, Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Vinh Sinh. 2009. ed. and trans. Phan Châu Trinh and his political writings, Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program.

In particular, the author thanks Alec Gordon for soliciting this article first published as part of a special edition on the Great War, “‘Mort pour la France,’: Coercion and Co-optation of ‘Indochinese’ Worker-Soldiers in World War One,” Social Scientist, vol.43, nos 7-8 (July-August 2014, pp. 63-84).