Abstract: In this essay I provide an account of a series of commemorative events held in Eastern Australia since the compound disaster of March 2011 occurred in Fukushima in Northeastern Japan. Individuals expressed transnational solidarity through the embodied experience of attending and participating in local events. Reflecting on these events reminds us of the entangled and mutually imbricated histories of Japan and Australia, and the ways in which various individuals and groups are positioned in the global networks of nuclear power and nuclear weaponry.

Keywords: Japan, Australia, Commemoration, Social Movements, Disasters, Atomic Energy, Nuclear Power

March 2011

The compound disaster of 11 March 2011 unfolded under a global gaze.1 People around the world saw the devastation wrought by the earthquake and tsunami thanks to footage taken on mobile phones and disseminated through Facebook, Twitter and other social media, and re-broadcast via both conventional media and the internet. All over the world, people could watch the progress of events on the national broadcaster NHK or on live-stream sites like Nico Nico Dōga. CNN immediately dispatched several journalists to Japan who provided continuous coverage. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Tokyo correspondent also covered the issue comprehensively.2

Thanks to new social media, the demonstrations, concerts, commemorations and anniversaries of the multiple disasters of March 2011 were also accessible to a global audience. In disparate places around the world, people gathered in commemoration and mourning – in the immediate aftermath and on significant anniversaries since then. In this essay I will consider the transnational dimensions of the disaster and its aftermath, through an account of a series of commemorative events held in Australia.3 While much discussion of transnational connectedness focuses on the “virtual” – the apparently disembodied connections made through social media, I argue that we should not neglect the embodied dimensions of events and rituals. New social media have not superseded gatherings in public places. Rather, virtual communications and public actions complement each other. Solidarity is forged when people come together in public places to express shared emotions. A micro-level analysis of specific events can give insights into the processes whereby feelings of transnational connectedness and solidarity are mobilised, as I discuss below. This will necessarily involve the “thick description”4 of details of these events.

I was a long way away from Japan on 11 March 2011, the onset of the compound disaster which involved earthquakes and aftershocks, a tsunami and a nuclear crisis. Nevertheless, I immediately became aware of the disaster through television, radio and social media. The television news repeatedly showed footage of the huge black wave of water and debris that devastated northeastern Japan. The fact that Australia and Japan are in similar time zones added further immediacy.5 I was able to make contact with friends in Japan through e-mail, Facebook and messages relayed by mutual friends. Meanwhile, my friends in Tokyo described via e-mail their experiences of being stranded or having to walk home because the trains had stopped. They often interrupted the flow of their e-mails with phrases like “a! yureteru” (it’s shaking) or “mata yureteru” (here we go again) when another aftershock hit. These phrases appeared regularly in Facebook posts in the ensuing months.

Although the earthquake largely hit the northeast of Japan and surrounding seas, the effects of the tsunami were experienced in Hawai’i, the Philippines, Pacific island nations, and the Pacific coast of the Americas, resulting in damage to ports and coastal settlements. Even on the Australian coast there was a measurable increase in the size of waves, though not enough to cause any damage.6 Years later, we are still seeing reports of debris washing up on the other side of the Pacific.7 Traces of plutonium were detected on the other side of the ocean, too.8 The effects of the nuclear meltdowns, explosions and the leakage of contaminated water could not be contained within the notional boundaries of the Japanese nation-state or its coastal waters. In addition to the damage wrought by the earthquake and tsunami, the winds and sea currents took radioactive contamination well beyond Japan’s national borders.

The crisis was transnational in the sense of being experienced (albeit at second-hand for many) through global media and social media. People around the globe – as I did – saw the devastation wrought by the tsunami on a combination of social media and conventional media. In the US, a survey revealed that close to 60 per cent of the public there were following the issue during March 2011.9 This was also the occasion for a global outpouring of empathy, sympathy and solidarity. As Slater, Nishimura and Kindstrand note, with respect to the new social media that facilitated communication about the disaster, “what were once considered the personal, private, even intimate domains of micro-sociality became engaged in an alternative politics that reached others around the world”.10

This emotional response was followed up by charity campaigns, through conventional charity organisations such as the Red Cross, overseas offices of such organisations as the Japan Foundation, overseas non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and links from the websites of news organisations like CNN. In the U.S., the Red Cross advertised during the Super Bowl (one of the major sporting events of the year with the highest television viewership) to solicit donations for the Tōhoku relief effort.11 In February 2012, the Japan Red Cross reported that it had transferred U.S.$4.5 billion to affected communities, of which U.S.$4 billion came from international donors (excluding sister Red Cross societies).12

In addition to the international humanitarian focus, there was also a burgeoning international movement against nuclear power – building on over half a century of activism.13 As the movement against nuclear power developed, those of us who could not attend the various demonstrations in Japan watched from afar through links provided by social media. Demonstrations and commemorations in solidarity with our friends in Japan were also held in various parts of the world, including New York, Paris and various Australian cities.14 Activists in Japan increasingly addressed an international audience, such as the “Mothers of Fukushima”, who disseminated an English-language video on YouTube to express their concerns about the safety of their children.15 The reference points for understanding were also international, with comparisons being made with the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the former Soviet Union, the Three Mile Island incident in the U.S., the Bhopal chemical pollution incident in India and Hurricane Katrina in the U.S. Japan’s experience of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was also referenced.16 This list includes place names which are instantly recognised throughout the world as heralding the nuclear age.17 During the summer of 2012, the anti-nuclear movement took on the name “hydrangea revolution” (ajisai kakumei) for a time, making links with the concurrent Arab Spring, the Occupy Movement and the “jasmine revolution” in Tunisia.18

The “3/11” compound disaster also galvanised expatriate Japanese communities and their supporters. As soon as the terrible news of the disaster came through, vigils were held in capital cities and regional centres across Australia. In Melbourne, for example, a vigil was held in the city centre on the evening of 17 March 2011, on the steps of the former General Post Office Building. The steps were decorated with a flock of giant origami cranes and rows of candles. Every March since then, commemorative events have been held on each anniversary. Given the close connections between the issue of nuclear irradiation at Fukushima and at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Fukushima is remembered once again every August on Hiroshima Day and Nagasaki Day. There is now an annual rhythm of events in March and August. At each event the connections between these historical events have been explored in more detail and with more subtlety. By an iterative effect, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are constantly being re-remembered, but now through the prism of Fukushima. The organisations that hold these events have built up a repertoire of symbols and practices which carry over from event to event and from year to year, as we shall see below.

Figure 1: Flock of origami cranes at vigil for Fukushima, March 2011, Melbourne. Photograph by Kaz Preston.19 |

March 2012

On 11 March 2012, one year after the disaster, I stood on the steps of the State Library of Victoria in Melbourne, feeling the reverberations of taiko drumming. Around me was a crowd of people who had gathered to commemorate the first anniversary of the losses from the combined earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown.

The lawn in front of the State Library in central Melbourne is commonly used for demonstrations or as the assembly point for marches. The stepped space provides the feeling of an agora or arena. On this day a utility truck was parked at street level and the bed of the truck provided a stage for speakers and performers. It was cluttered with microphones and amplifiers and a bank of taiko drums. Opposite the State Library is a shopping complex known as Melbourne Central, originally built by Japanese business interests during the “bubble years”. It formerly hosted a branch of the Japanese department store Daimaru, but Daimaru closed down after the bursting of the bubble economy. The street between the State Library and the shopping complex is a pedestrian mall – the only traffic being trams, bicycles and pedestrians. The location of the demonstration in the middle of the business and shopping district meant that there was an easy flow between the different activities of the city. Some people may well have interrupted their shopping or library research to join the commemoration and demonstration. Others just observed from the surrounding streets or through the windows of the trams which rattled by every few minutes.

Children milled about, offering masks to the assembled crowd. The masks were yellow and black, a hybrid image combining the international sign denoting nuclear radiation and a face that mimicked Edvard Munch’s (1863–1944) painting of 1893, “The Scream”.20 Variations on this black-and-yellow sign for radiation also featured in demonstrations in other parts of the world. These graphic symbols were originally designed to warn of the danger of radioactivity in a way that transcended particular languages. In their adaptations, the new versions of the symbol have helped to forge a visual vocabulary of transnational activism. One demonstrator was dressed as a giant sunflower, the symbol of solar power – an alternative to nuclear energy and fossil fuels. Some children were dressed in red “oni” (devil) costumes symbolising the evil of nuclear power. A few carried origami cranes.

Figure 2: Photograph of Demonstrator at Commemorative Event in Melbourne, March 2012. Photograph by Tim Wright.21 |

I was not able to comprehensively survey the crowd, but my impression is that it was made up of a combination of long-term immigrants and residents of Japanese heritage, academics, students, working holiday-makers and tourists, Australians with ties to Japan, Australians with a commitment to the anti-nuclear issue, and journalists. Several speakers and demonstrators noted Australia’s connections with the disaster, for uranium from Australian mines has fuelled nuclear power plants in Japan.22 Some of the demonstrators carried placards saying that “Australian Uranium Fuelled Fukushima”, reminding the Australian audience of our own connection with these events, through the mutual imbrication of the Australian and Japanese economies. Later, some participants marched to protest outside the headquarters of the mining companies BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto.23

Marching, carrying placards and wearing masks and costumes were embodied expressions of solidarity. Participants were also enjoined to chant phrases together at various points. They learned the Japanese phrase “genpatsu hantai” (oppose nuclear power) and the taiko drummers beat time on each syllable to provide a rhythm for the chant. The use of the Japanese phrase was an explicit address to Japanese-speaking viewers of the UStream. There was also a call and response in English: “Uranium mining? End it now!” and “Fukushima! Never again!”. Through co-ordinated actions like chanting and marching together, the individuals came to feel part of a collectivity, at least for the duration of the demonstration.24

A major sponsor of the demonstration was a local NGO, Japanese for Peace, which co-operated with other local organisations devoted to pacifism, environmental issues, the anti-nuclear cause and the issue of Aboriginal self-determination.25 Most speakers acknowledged the original Aboriginal custodians of the land they stood on – the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation – as is the practice at such public events in Australia. Other speakers came from the Greens Party and the Australian chapter of the International Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). A remote indigenous community sent a message that was broadcast both in their indigenous language and English. A message from an anti-nuclear organisation in Fukushima was read out in English translation too. The program was punctuated by interludes of taiko drumming. While the truck was being packed up in preparation for the march, the album “Human Error”, from Japanese performers Frying Dutchman blasted out from the speakers on the truck. While maybe only a small number of the participants could follow the anti-nuclear lyrics in Japanese, they would have responded to the raw punk energy of this poetic rant set to music.26

In front of me on the library steps, a journalist looked into a video-camera and presented a report for a television station back in Japan. Cameras, video-cameras and mobile phone cameras were ubiquitous on this occasion. People took photos and videos for their own records, to post on UStream, Youtube, Facebook pages, blogs, or the websites of their organisations. The commemoration and demonstration was streamed live, so that anyone with an interest could tune in from around the world. The UStream video had occasional voiceovers in Japanese, commenting at times and translating parts of the mainly English-language speeches for a Japanese-speaking audience. In other words, new social media enabled a series of rhythmical feedback loops. While people in Melbourne and other cities followed the progress of the anti-nuclear movement in Japan through social media, they also broadcast their own activities to their friends and comrades in Japan.

March 2013

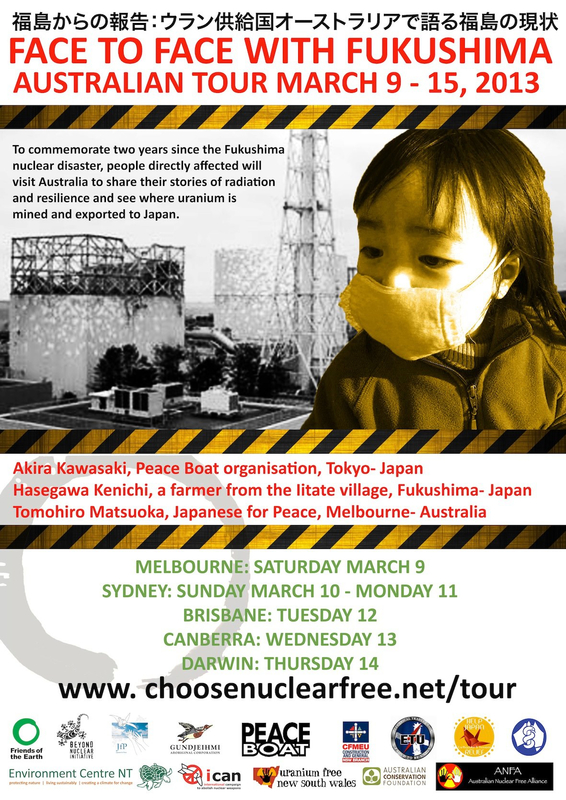

One year later, around the second anniversary in March 2013, survivors of the disaster toured Australia to tell of their experiences. The tour was called “Face to Face with Fukushima”, and was sponsored by an organisation called “Choose Nuclear Free” (formed through a collaboration between Friends of the Earth, Australia, the Medical Association for the Prevention of War, and ICAN). In each state, other local organisations co-operated in staging events. As well as touring several state capital cities, the group visited the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra and the Ranger Uranium Mine in the Northern Territory, where they met with members of local indigenous communities.

Figure 3: Poster for “Face to Face with Fukushima Australian Tour, March 9-15 2013”.27 |

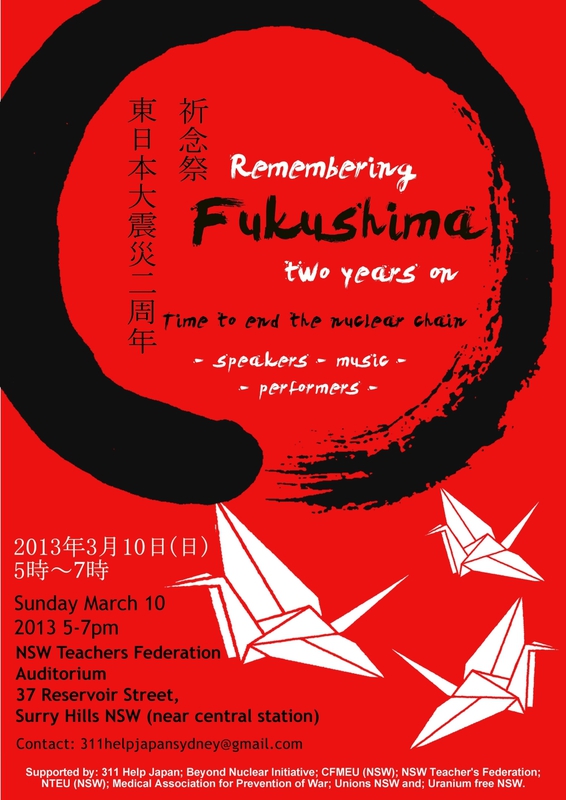

I attended the Sydney event to hear the testimonies of individuals who had been directly affected by the Fukushima disaster. Hasegawa Ken’ichi, a farmer from Iitate village, testified to his experiences. Kawasaki Akira, a representative of Peace Boat, spoke; and we also heard from a representative of an indigenous community from the Illawarra region, south of Sydney. Matsuoka Tomohiro acted as interpreter and represented Japanese for Peace from Melbourne. In addition to the “Face to Face with Fukushima” speakers, there were performances and a photographic exhibition. The poster for this event had a rich red background. In the centre was a brushstroke forming a black circle, and the bottom right foreground was decorated with drawings of white origami cranes. In preparation for the event, organisers and supporters had also folded chains of origami cranes in remembrance. Origami has become an important element of commemoration at Fukushima-related events. It is well-known that cranes are linked with the story of Sasaki Sadako, a girl from Hiroshima who died of leukemia in the 1950s. As an infant, she had been only a kilometre away from ground zero when the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. In her final stay in hospital she tried to fold one thousand paper cranes, as there is a legend that wishes will be granted to someone who does this. She died, however, before completing the one thousand, and the remainder were completed by her family.28 Origami cranes have now become an international symbol of peace, memorialisation and the anti-nuclear cause.29 When people come together to fold origami cranes, string them together, and then present them as a tribute, this is an embodied practice which expresses solidarity.

Figure 4: Poster for “Remembering Fukushima: Two Years On”. |

August 2013

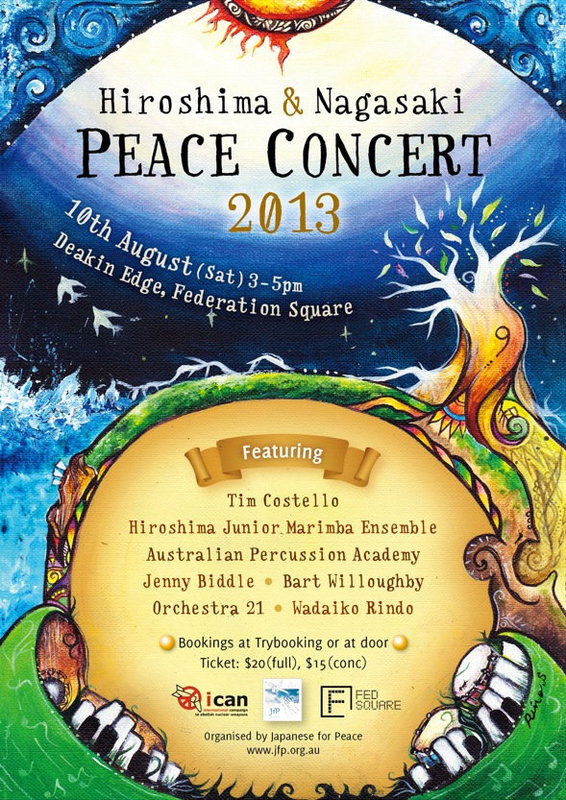

Japanese for Peace, one of the organisations sponsoring the Melbourne events, was formed in 2005 (the sixtieth anniversary year of the end of the Second World War) by some members of the expatriate Japanese community in Melbourne. They were concerned to go beyond the negative memories of the Second World War, when Japan and Australia had been antagonists. Japanese for Peace were keen to build new connections between citizens in Australia and Japan.30 Over the last decade they have conducted a series of community events, focusing on such issues as enforced military prostitution/military sexual slavery in the Second World War, the “pacifist clause” (Article 9) of the Constitution of Japan, and nuclear issues. In August every year they hold a peace concert in commemoration of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Since 2011, these commemorative events have brought together the issues of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Fukushima as well as connections with the nuclear industry, nuclear mining and nuclear testing in Australia.

In August 2013, the commemorative concert was held at Deakin Edge, a venue for concerts, symposia and various public events. It is part of an arts complex right in the city centre of Melbourne. The arts venues encircle a public space –Federation Square –where people regularly gather for community festivals, demonstrations, or to watch sporting events on the big screen. Unusual for such a venue, the wall behind the stage at Deakin Edge is glass. While the concert proceeded, other activities took place on the other side of the glass. I could see people rowing, jogging, cycling, skateboarding, strolling along, eating ice creams, picnicking, taking wedding photos. The life of the city on a mild weekend afternoon provided a backdrop for the concert.

Over the last decade these concerts and events have built up a repertoire of elements which are repeated and adapted from year to year. The iconography of the posters and fliers draws on recognisable symbols: the dove, the peace symbol, the candle of remembrance, the origami crane and images of nature. In the logo of the organisation, an origami crane is shown being released from two hands, appearing to fly into a blue sky like a dove being released to symbolise peace.

On entering Deakin Edge for the 2013 concert, the venue was full of psychedelic colours. On the back of each seat was a cardboard placard in hot pink, canary yellow or lime green. Each placard bore a peace symbol in red, with a white shape that looked like a broken missile.33 The placards were made by local children and children visiting from Japan. The logo is that of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), one of the sponsors of the event. As the concert proceeded, it became clear that these placards were more than just decorations.

When ICAN representative Tim Wright spoke, he invited each participant to take the placard from their seat and hold it up in front of them. As with the placards carried by demonstrators at earlier events, this action meant that solidarity was expressed through each individual acting together with the 200-or-so other audience members. A group of people who had, until then, been sitting as an audience passively listening to speakers and performers were now the centre of action. Photographers took photos of the sea of lime green, canary yellow and hot pink and posted them on the ICAN website.34 Actions like this have much in common with performance art, where the distinction between performer and audience is blurred. Each person in the room became an integral part of the event, rather than just a spectator.35

|

|

| Figure 7: Japanese for Peace Logo.32 | Figure 8: Anti-nuclear logos on placards at Deakin Edge, Melbourne. Photograph by Vera Mackie. |

This action, however, was just one step in a chain of embodied actions. The placards themselves had been made by local and visiting Japanese schoolchildren, an activity that forged solidarity between children of different countries. As in the second anniversary event in March 2011 in Sydney, origami cranes also formed a part of the ritual. A representative from a local school presented a chain of origami cranes to a member of the visiting Hiroshima Junior Marimba Ensemble. Like the placards, behind this simple ritual was the time spent by local children folding the cranes and stringing them together. In these ways, the bonds of solidarity reached into local communities well beyond the few hundred people who attended the concert.

Another feature of these events is the inclusion of performers who practise Japanese performance arts. In previous years, this has included koto players, shakuhachi players and taiko drummers. There are numerous troupes of taiko drummers in Australia. They often perform at community events involving the Japanese community, events celebrating multiculturalism and diversity, or at openings of major Japan-related academic conferences. This could be seen as an example of ‘glocalisation’, where cultural practices from Japan are adapted and embedded in local communities. Taiko drumming is now a regular feature of Japanese for Peace demonstrations and concerts. This is quite a localised adaptation: In Japan, taiko are associated with local festivals and celebrations rather than political demonstrations.36 The Wadaiko Rindō drumming group played a major role in the 2013 concert.

Rather than sending messages through speeches, the concert itself was structured so that solidarity could be expressed through music and performance. There were very short speeches from Tim Costello (the CEO of international development agency World Vision), Tim Wright (Australian Director of ICAN), Japanese for Peace co-founder Kazuyo Preston, and MCs Matt Crosby and Sara Minamikawa. The sequencing of the acts created meaning through the juxtaposition of, for example, the local chamber music ensemble Orchestra 21, the Australian Percussion Academy, Wadaiko Rindō and the Hiroshima Junior Marimba Ensemble. These different kinds of music and percussion from different countries provided a tangible expression of diversity. Then, when the different groups jammed together they performed co-operation and solidarity.

Among the highlights of the concert were the sets performed by the Hiroshima Junior Marimba Ensemble. The group was established in Hiroshima by Asada Mieko in 1991. The members of the ensemble all seem to be of primary school age, and play the marimba (a kind of percussion instrument similar to a xylophone), maracas, drums and whistles with extraordinary energy. As the troupe comes from Hiroshima, they are easily associated with anti-nuclear and pacifist issues. This is the reason that local children presented them with the chains of origami cranes. Their music is in many ways a festive performance of the forms of hybridity often associated with globalisation. A group of Japanese children perform a Latin American style of music, transposing melodies from Japan, China and Europe into this style. In one set, however, they brandish Japanese and Australian flags. This is, of course, a gesture for the benefit of the Australian audience, but the use of national symbols was at odds with the tone of the rest of the event. Nevertheless, the audience was captivated by a youthful energy which is hard to capture in words. The ensemble did not just play their percussion instruments, they leapt around the stage, performed Chinese dragon dances, and ran from one end of the auditorium to the other while the audience marked time by clapping their hands.37

The program also included Australian indigenous performer Bart Willoughby, known for fronting the pioneering indigenous rock band “No Fixed Address”.38 There were no speeches about indigenous issues. Rather, Willoughby’s presence signalled an acknowledgment of the relevance of indigenous concerns, and a recognition of the importance of music in indigenous politics. Aboriginal Australians suffered from irradiation in the 1950s when the British conducted atomic tests in Maralinga in central Australia; and the uranium mines in Australia are on indigenous land, albeit managed by transnational mining corporations.39 The inclusion in the concert of the Hiroshima Junior Marimba Ensemble, local Australian music ensembles, the Melbourne-based Wadaiko Rindō and Bart Willoughy demonstrated a recognition of the mutual connectedness of the survivors of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Fukushima and Maralinga. Both the Australian and Japanese economies benefit from the dispossession of indigenous land and the buying and selling of resources mined on those lands. The shared presence of these different groups might also invite reflections on these relationships of inequality between individuals and groups at different points on the nuclear cycle.

Conclusion

In the years since the Fukushima compound disaster, a series of commemorative events have been held around the world. In this essay I have focused on events in Eastern Australia, mainly in the city of Melbourne. These events have built on a pre-existing repertoire of practices and symbols, while also creating new practices and new ways of performing and representing feelings of empathy, solidarity and connectedness. These events often defy categorisation, blending elements of commemoration, demonstration, political activism and, at times, festival.

Individual feelings of sadness, concern and anger are brought together as collective expressions of solidarity through a range of embodied practices: preparing placards, folding origami cranes, stringing them together, carrying placards in demonstrations, presenting strings of origami cranes to visitors, marching through the streets, chanting in call and response sequences, clapping in time to a musical rhythm, or coming together for a group photograph of a mass of colourful anti-nuclear placards.

The iconography of these events also draws on pre-existing symbols, at times investing them with new meanings. The peace symbol, which began as a logo designed for a specific anti-nuclear event in 1950s Britain, has become a transnational symbol for pacifism. The symbol for radioactivity is still recognisable as such, but its very recognisability makes it easily parodied for use in association with anti-nuclear messages. The origami crane has moved from a folk practice in Japan to a more specific association with the aftermath of Hiroshima; and the practice of folding origami cranes has been adopted around the world as a gesture of sympathy and solidarity for the suffering of Hiroshima. It has now been adapted, at least in Australia, to express sympathy and solidarity for the suffering of Fukushima. In some visual texts, the origami crane takes on some characteristics of the white dove of peace.

Events commemorating the compound disaster of Fukushima also reference the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In place of the catchphrase “No more Hiroshima, no more Nagasaki” we now pronounce “No more Hiroshima, no more Nagasaki, no more Fukushima”.40 Each one of these place names now references the others. Each iteration of these commemorative events reinforces the connectedness of these events and places. When we remember Hiroshima, we now remember it through the prism of Fukushima, leading to a new understanding of the nuclear cycle in which we are entangled.

The events described here have been enacted in key sites around the city of Melbourne (and other major cities). The concerns of a rather small group of interlocking activist networks and community organisations have thus been imprinted on the streets of the city. For many participants and spectators, these commemorative events are overlaid with memories of other demonstrations, vigils and events that have taken place on the same sites. Indeed, these become embodied memories, reactivated each time we march through the streets or chant the call and response.

In the particular context of Australia, the inclusion of indigenous Australian participants in these commemorative events reminds us of our place in the global nuclear cycle. The economies of Japan and Australia are bound together through the import and export of uranium and other mineral resources. Our histories are bound together through a past of conflict and a present of diasporic movements. The transnational history of nuclear testing, nuclear power generation and nuclear weaponry ties together the Manhattan project in Nevada, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear testing in the Pacific and outback Australia, uranium mining in outback Australia, and the recent tragedy in Fukushima. Through the repetition of commemorative rituals, memories of tragic events are constantly being reframed.

No more Hiroshima.

No more Nagasaki.

No more Fukushima.

No more Maralinga.

Recommended Citation: Vera Mackie, “Fukushima, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Maralinga ( フクシマ、ヒロシマ、ナガサキ、そしてマラリンガ)”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 13, Issue 6, No. 5, February 16, 2015.

Notes

1 This essay draws on research completed as part of an Australian Research Council-funded project ‘From Human Rights to Human Security: Changing Paradigms for Dealing with Inequality in the Asia-Pacific Region’ (FT0992328). I would like to express my thanks to Kazuyo Preston and Tim Wright for permission to reproduce their photographs and posters. I am also grateful to Laura Hein (editor, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus), my co-editor Alexander Brown, and the journal’s reviewers for constructive comments on earlier drafts.

2 Mark Willacy, Fukushima: Japan’s Tsunami and the Inside Story of the Nuclear Meltdown, Sydney, Pan Macmillan Australia, 2013.

3 See also: Vera Mackie, “Reflections: The Rhythms of Internationalisation in Post-Disaster Japan”, in Jeremy Breaden, Stacey Steele and Carolyn Stevens (eds.), Internationalising Japan: Discourse and Practice, London, Routledge, 2014, pp. 195–206.

4 Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, New York, Basic Books, pp. 3–30.

5 I was reminded of the experience of watching the events of 11 September 2001 (“9/11”) unfold on my television screen in Melbourne over a decade ago. Once the abbreviation “3/11” started to be used, this provided further resonance with “9/11”. In the decade since “9/11” the advances in new social media have made huge differences in the speed with which information can be disseminated. Smart phones, for example, make it easy for individuals to disseminate photographs or videos of catastrophic events before conventional media appear on the scene.

6 Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology, “Tsunami Event Summary, Friday 11 March 2011”. Retrieved on 2 April 2014.

7 “Japan Tsunami Victim’s Soccer Ball Found in Alaska”, San Francisco Chronicle, 23 April 2012. Retrieved on 25 July 2012; “Workers Cut Up Tsunami Dock on Oregon Beach”, Japan Times, 3 August 2012. Retrieved on 4 August 2012.

8 Atsushi Fujioka, “Understanding the Ongoing Nuclear Disaster in Fukushima: A ‘Two-Headed Dragon’ Descends into the Earth’s Biosphere”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 9, iss. 37, no. 3, 2011. Translated by Michael K. Bourdaghs. Retrieved on 25 July 2012.

9 Leslie M. Tkach-Kawasaki, “March 2011 On-Line: Comparing Japanese News Websites and International News Websites”, in Jeff Kingston (ed.), Natural Disaster and Nuclear Crisis in Japan: Response and Recovery after Japan’s 3/11, London, Routledge, 2012, pp. 109–23.

10 David H. Slater, Keiko Nishimura and Love Kindstrand, “Social Media, Information and Political Activism in Japan’s 3.11 Crisis”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, 2012. Retrieved on 24 July 2012.

11 Slater, Nishimura and Kindstrand, “Social Media, Information and Political Activism in Japan’s 3.11 Crisis”.

12 Jennifer Robertson, “From Uniqlo to NGOs: The Problematic ‘Culture of Giving’ in Inter-Disaster Japan”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 10, no. 18, 2012. Retrieved on 27 July 2012.

13 March 2014 marked the sixtieth anniversary of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon No 5) Incident, almost coinciding with the third anniversary of the Fukushima Disaster. The irradiation of the crew of the Lucky Dragon was a major impetus for the international nuclear disarmament campaign in the 1950s.

14 John F. Morris, “Charity Concert, Paris, for Quake/Tsunami Victims”, H-Japan Discussion List, 19 March 2011. Retrieved on 8 August 2012. Japan: Fissures in the Planetary Apparatus. 2012. Retrieved on 17 August 2012.

15 “Heartfelt appeal by Fukushima mothers”, 17 May 2011. Retrieved on 24 July 2012; Junko Horiuchi, “Moms rally around anti-nuke cause”, Japan Times, 9 July 2011. Retrieved on 17 August 2012; David H. Slater, “Fukushima Women against Nuclear Power: Finding a Voice from Tohoku”, The Asia-Pacific Journal. Retrieved on 17 August 2012.

16 See the essays by Brown, Kilpatrick and Stevens in this issue.

17 To be more precise, the nuclear age started with the Manhattan Project and nuclear testing in the Nevada desert, but it is the names of “Hiroshima” and “Nagasaki” that have instant recognition. Oda Makoto, in his novel Hiroshima, translated as The Bomb, was one of the first to explore the global dimensions of the nuclear age, including nuclear testing in the Pacific and outback Australia. Oda Makoto, Hiroshima, Tokyo, Kōdansha, 1981; Oda Makoto, The Bomb, translated by D. Hugh Whittaker, Tokyo, Kodansha International, 1990. As I discuss below, the name ‘Maralinga’, where indigenous Australians and military personnel suffered the effects of British atomic testing in outback Australia in the 1950s, should also be added to this list.

18 Manuel Yang, “Hydrangea Revolution”, Japan: Fissures in the Planetary Apparatus, 2012. Retrieved on 13 August 2012; Slater, Nishimura and Kindstrand, “Social Media, Information and Political Activism in Japan’s 3.11 Crisis”.

19 Kaz Preston’s Gallery. Retrieved on 3 April 2014.

20 See Alexander Brown’s discussion (in this issue) of Chim↑Pom, who transformed a white flag successively into a Japanese national flag with a red circle, and then into a red version of the radioactivity symbol. See a similar morphing of the radioactivity symbol into a human face on a notice for a vigil in Boston. Retrieved on 3 April 2014.

21 “Photos of 11 March Day of Action in Melbourne”. Retrieved on 2 April 2014. See also the UStream video. Retrieved on 3 April 2014.

22 While beyond the scope of this essay, the establishment of the nuclear power industry in post-war Japan was also an international affair, involving advice from such US corporations as General Electric. More recently the Japanese nuclear power industry has been involved in the international promotion of the nuclear industry in third world countries. Yuki Tanaka and Peter Kuznick, “Japan, the Atomic Bomb, and the ‘Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Power'”, The Asia-Pacific Journal vol. 9, iss. 18, no. 1, 2011. Retrieved on 13 August 2012; Craig D. Nelson “The Energy of a Bright Tomorrow: The Rise of Nuclear Power in Japan”. Origins vol. 4, no. 9, 2011. Retrieved on 17 August 2012; Philip Brasor, “Nuclear Policy was Once Sold by Japan’s media”, Japan Times, 22 May 2011. Retrieved on 17 August 2012.

23 Australia holds an estimated 31 per cent of the world’s uranium resources. World Nuclear Association, “Australia’s Uranium”. Retrieved on 2 April 2014. As at the end of 2008, Japan bought around 23 per cent of Australia’s uranium exports. Clayton Utz, Uranium Mining Policy in Australia, Sydney, Clayton Utz, March 2013, p. 5. Retrieved on 2 April 2014, from http://www.claytonutz.com.au/docs/Uranium_Mining_Policy.pdf. TEPCO buys 30 per cent of its uranium from Australia. Although a major supplier of uranium to the international nuclear power industry, Australia does not generate nuclear power, except for one scientific reactor in Sydney’s Lucas Heights. The decision to export uranium in the 1970s was controversial and brought anti-nuclear demonstrators out on to the streets of capital cities (part of my own memories from student days) and to the remote indigenous communities where the mines were established. See Brian Martin, “The Australian Anti-nuclear Movement”, Alternatives: Perspectives on Society and Environment, vol. 10, no. 4, 1982, pp. 26–35; Helen Hintjens, “Environmental Direct Action in Australia: The Case of the Jabiluka Mine”, Community Development Journal, vol. 4, no. 4, 2000, pp. 377–390; Alexander Brown, “Globalising Resistance to Radiation”, Mutiny, 18 August 2012. Retrieved on 13 April 2014. Matsuoka Tomohiro, “Uran Saikutsuchi kara Fukushima e no Ōsutoraria Senjūmin no Manazashi” [The Gaze of Australian Indigenous People from the Uranium Mining Area to Fukushima], in Yamanouchi Yuriko (ed.) Ōsutoraria Senjūmin to Nihon: Senjūmingaku, Kōryū, Hyōshō [Australian Indigenous People and Japan: Indigenous Studies, Connections and Representation], Tokyo, Ochanomizu Shobō, 2014, pp. 165–185.

24 On the embodied dimensions of demonstrations see also: Vera Mackie, “Embodied Memories, Emotional Geographies: Nakamoto Takako’s Diary of the Anpo Struggle”, Japanese Studies, vol. 31, no. 3, 2011, pp. 319–331.

25 Japanese for Peace. “11 March Day of Action to End Uranium Mining: Fukushima One Year On”. Retrieved on 13 August 2012 . This organisation will be discussed further below.

26 For the lyrics of Human Error in Japanese and English, see the website Human Error Parade. Retrieved on 3 April 2014.

27 The poster was retrieved on 2 April 2014.

28 Eleanor Coerr, Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, New York, Putnam, 1977.

29 For an example of the origami crane as an expression of solidarity, see the photograph of Kawasaki Natsu (1889–1966) presenting an origami crane to a Latvian child on a tour of the Soviet Union after attending the Women’s International Democratic Federation’s World Congress of Mothers in Lausanne in 1955. “Nihon no Haha Soren o Iku” [Japanese Mothers go to the Soviet Union], Ōru Soren [All Soviet Union], Vol. 2, No 1, 1956, p. 68. On the Japanese women’s participation in the World Congress of Mothers (where the nuclear issue was a major theme in the year after the Lucky Dragon Incident), see Vera Mackie, “From Hiroshima to Lausanne: The World Congress of Mothers and the Hahaoya Taikai in the 1950s”, Women’s History Review, in press.

30 Japanese for Peace. ‘About JfP’. Retrieved on 13 August 2012. Despite the name, not all of those associated with the group are of Japanese nationality or ethnicity. I have been involved with the group in the past as a speaker at their seminars. For the purposes of this essay, however, I draw only on publicly available information.

31 The poster was retrieved on 2 April 2014.

32 The logo was retrieved on 2 April 2014.

33 The peace symbol (a circle bisected by a vertical line, with two more diagonal lines), was designed by Gerald Holtom for the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1958. The vertical line is the semaphore signal for the letter “D”, while the line with two “arms” pointing down is the semaphore signal for “N”. Together, they spell the initials of “Nuclear Disarmament”. The symbol is now widely used in peace movements and anti-nuclear movements. Ken Kolsbun with Mike Sweeney, Peace: The Biography of a Symbol, Washington DC, National Geographic, 2008.

34 See the photograph. Retrieved on 2 April 2014.

35 See my discussion of Yoko Ono’s performance pieces from the 1960s, where there was a similar blurring of the roles of spectator and performer. It is interesting that Ono herself moved from quite abstract happenings and performance pieces to happenings with a more overtly political intent, such as the “Bed-In for Peace” with John Lennon and the constant reworking of “Cut Piece”. Vera Mackie, “Instructing, Constructing, Deconstructing: The Embodied and Disembodied Performances of Yoko Ono”, in Roy Starrs (ed.), Rethinking Japanese Modernisms, Leiden, Global Oriental, 2012, pp. 490–501. Ono is one of the celebrities who sends a message of solidarity on the ICAN website. Retrieved on 5 April. See here.

36 On glocalisation, see: Anne Allison, Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2006, p. 281, n. 4. On taiko drumming as a global phenomenon, see Shawn Morgan Bender, Taiko Boom: Japanese Drumming in Place and Motion, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2012.

37 See: “Hiroshima Junior Marimba Ensemble JFP 2013”. Retrieved on 5 April 2014.

38 On these performers see: https://www.facebook.com/bartwilloughbyband.willoughby; www.orchestra21.org.au; www.percussionacademy.com.au; www.wadaikorindo.com; www6.ocn.ne.jp/~marimba. Retrieved on 4 April 2014. On “No Fixed Address” and the place of music in indigenous Australian politics, see Chris Gibson, “‘We Sing Our Home, We Dance Our Land’: Indigenous Self-determination and Contemporary Geopolitics in Australian Popular Music”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 163–184.

39 See: ICAN, Black Mist: The Impact of Nuclear Weapons in Australia, Carlton, ICAN, 2014. Retrieved on 5 April 2014.

40 See, for example, this blogger’s reflection on the first Hiroshima anniversary after Fukushima (that is, August 2011). Retrieved on 5 April 2013.