Abstract: In May 2011, just one month after the 3/11 triple-disaster, the Chim↑Pom artist collective conducted an unauthorised installation of a panel depicting the crippled nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant next to Okamoto Tarō’s large-scale mural Myth of Tomorrow in Shibuya railway station. In this paper I read the installation as a commentary on the history of nuclear power and anti-nuclear art in post-war Japan. This commentary reconnects the historical issue of nuclear weapons with contemporary debates about nuclear power.

Keywords: Graphic Arts and Photography, Disasters, Atomic Energy/Nuclear Power, Atomic Bomb and Nuclear War

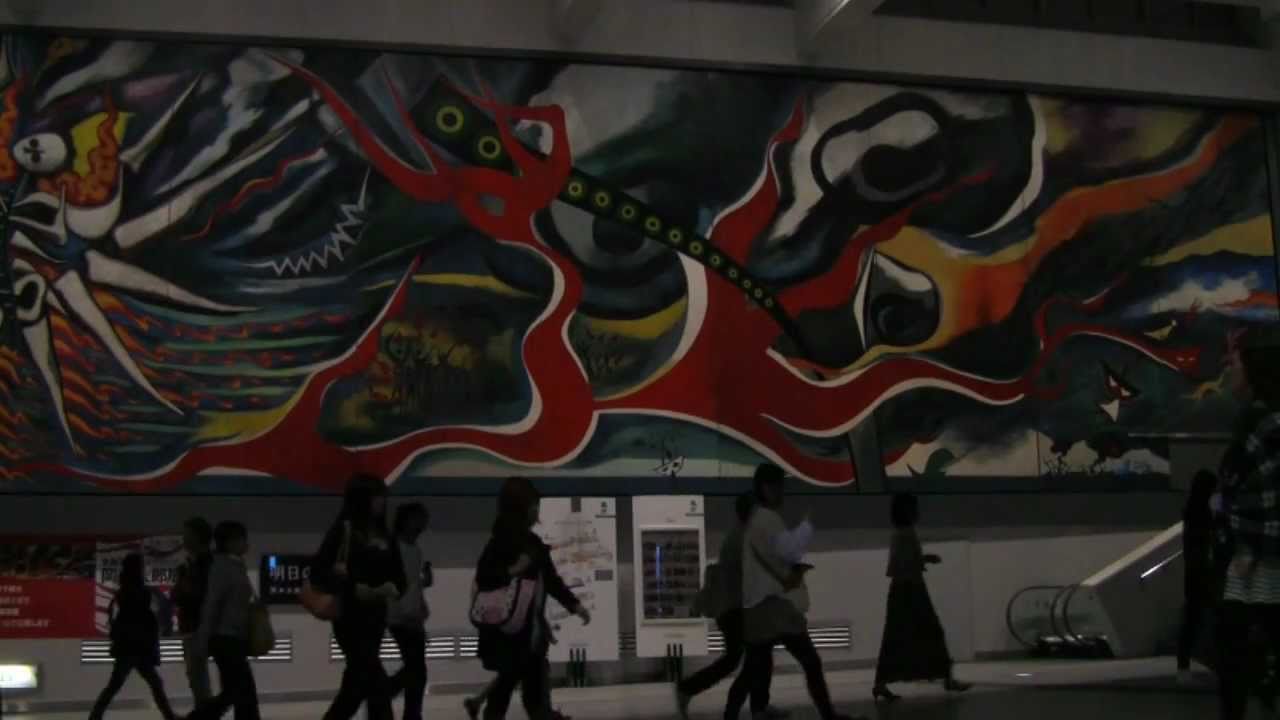

In a large airy corridor of Tokyo’s Shibuya railway station hangs Myth of Tomorrow (Asu no shinwa), an enormous 5.5 metre by 30 metre mural by the late Okamoto Tarō (1911–1996), one of twentieth-century Japan’s best known artists. At the centre of the mural is the dramatic motif of a burning skeleton which represents Japan’s first two encounters with the terrible power of the atom at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. In the bottom right hand corner of the mural is depicted the third: the Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon No 5), a Japanese tuna fishing trawler whose crew members were exposed to radioactive fallout from the U.S. “Bravo” hydrogen bomb test conducted in 1954 at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. On 30 April 2011, nearly two months after the Great East Japan Earthquake shook Japan and triggered a series of explosions at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, a small one metre by two metre panel appeared in an empty space in the bottom right hand corner of the mural. The panel, which blended seamlessly with the original mural, depicted this fourth and most recent major radioactive disaster in Japan’s history. Black smoke rising from the smouldering ruins of the reactors in the panel was painted so as to resemble Okamoto’s own haunting representation of the mushroom cloud, which rises from the skeleton at the centre of his mural.

Level 7 feat. “Myth of Tomorrow”, Chim↑Pom, 2011.

By cleverly incorporating the Fukushima disaster alongside Okamoto’s depiction of the atomic bomb, Chim↑Pom’s work drew a connection between the experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the nuclear disaster at Fukushima. In this essay I read Chim↑Pom’s LEVEL 7 in order to reflect on a question which has puzzled so many activists and observers in the wake of Fukushima: how a nation which experienced the horror of nuclear war could embrace the peaceful use (heiwa riyō) of nuclear power and become the world’s third-largest producer of nuclear energy. It took a major propaganda campaign conducted throughout the 1950s and 1960s to separate the memory of the atomic bomb and the Lucky Dragon from the idea of a “peaceful use” for nuclear power.7 By reconnecting the two issues, LEVEL 7 helps us to visualise the struggles and the competing “myths of tomorrow” which have shaped Japan’s encounter with the atom from 1945 to the present day.

I begin this essay by analysing Okamoto’s Myth of Tomorrow and showing how the artist’s ideas on anthropology, nuclear war and art practice influenced the production of the work. Okamoto produced Myth of Tomorrow while working as “theme producer” for a pavilion at the Osaka World Fair of 1970. I read Okamoto’s depiction of the atomic bomb in Myth of Tomorrow alongside his critique of the World Fair’s theme of “progress and harmony” (shimpo to chōwa). Chim↑Pom’s intervention, I argue, exposes the connection between the dream of a peaceful, nuclear-powered, high-growth economy and the reality of Japan’s continued economic and military dependence on the United States. By juxtaposing their own work with Okamoto’s mural in “real-time”, Chim↑Pom help us to recognise the connection between Fukushima and Hiroshima and the hidden histories of nuclear power which have unfolded under the American “nuclear umbrella”.

Okamoto Tarō’s Myth of Tomorrow |

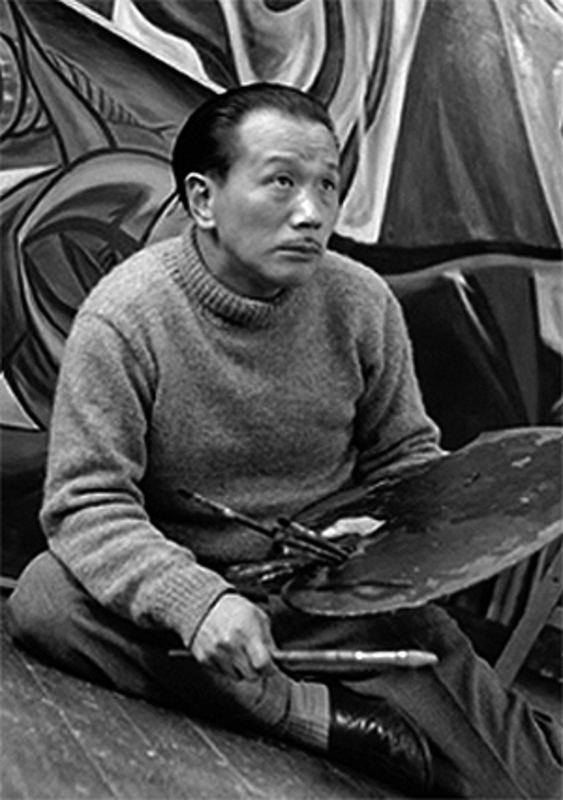

As an anti-war artist and a leading light in Japan’s post-war avant-garde, Okamoto Tarō played an important part in the rebellious and anti-establishment currents within Japanese contemporary art.8 After enrolling in the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1929 with the intention of becoming an artist, Okamoto studied for only half a year before leaving to accompany his parents to Paris. He arrived there in January 1930 and remained for a decade to pursue his studies of art and anthropology.9 In Paris, Okamoto studied anthropology with Marcel Mauss (1872–1950) and became involved in surrealist circles.10 War framed both the beginning and the end of Okamoto’s sojourn in Paris. It was his father, manga artist Okamoto Ippei’s (1886–1948), trip to cover the London Naval Conference of 193011 for the Asahi newspaper that provided the opportunity for Tarō to travel with his family to Paris in 1929; and it was the outbreak of war in Europe that forced Tarō to return to Japan in 1940. On his return, Okamoto was drafted for military service in China in 1942 where he served out the remainder of the war. He later referred to having been “frozen” during this “most futile part of my life”. Only a few portraits of his senior officers and sketches of soldiers remain from these years.12

Repatriated in June 1946, after having been interned in China for a year, Okamoto established a studio in Kaminoge in Tokyo’s Setagaya ward and began to produce socially-conscious art, including numerous works reflecting his opposition to war and nuclear weapons.13 In 1954 the Japanese tuna fishing trawler Lucky Dragon No 5 was exposed to fallout from the U.S. “Bravo” nuclear weapons tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The vessel’s return to the port of Yaizu in Shizuoka prefecture with its 23-member crew all suffering from radiation sickness sent shock waves through Japan and brought the popular movement against the hydrogen bomb onto the national and international stage.14 Okamoto’s Moeru hito (Burning People), composed in response to the Lucky Dragon, was exhibited as part of the Fifth World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in 1959, one of a series of anti-nuclear conferences organised in response to the Lucky Dragon incident. The work appeared alongside that of other prominent anti-nuclear artists such as Maruki Toshi (1912–2000) and Maruki Iri (1901–1995).15Moeru hito, art curator Ōsugi Hiroshi explains, was the first of Okamoto’s many atomic bomb-themed works and is painted “with the most intense and audacious composition”. For Ōsugi, Moeru hito evokes Picasso’s great anti-war mural Guernica, which Okamoto himself regarded as the crowning achievement of modern art and which inspired him in the composition of Myth of Tomorrow.16

|

|

| Moeru hito by Okamoto Tarō | Myth of Tomorrow by Okamoto Tarō |

The red flash which occupies the centre of Moeru hito reappears in Myth of Tomorrow as a potent representation of the destructive power of the atomic bomb. In the lower right hand corner of the mural we find the Lucky Dragon, caught up in a turgid wave of yellow that contrasts with the red flash of the hydrogen bomb. Okamoto represents the trawler with a face, body, arms and legs – evoking the terrible impact of the blast on the ship’s crew. This anthropomorphic figure is shown being blasted to one side by a large red streak which has its origins to the left of the central skeleton and reaches out to dominate the entire right half of the mural. It was in this bottom right-hand corner of Okamoto’s mural, below the representation of the Lucky Dragon, that Chim↑Pom installed their LEVEL 7 panel. This juxtaposition prompts us to consider the Fukushima disaster in the context of Japan’s multiple experiences of radiological disaster and its vibrant traditions of anti-nuclear activism.

While Okamoto explored the experience of war and its aftermath in his painting, in his anthropological work he applied the ideas he had developed in France to the study of the Japanese archipelago’s own neglected artistic traditions. As he waged war on the art establishment as part of the avant-garde, Okamoto tried to reclaim a neglected history of Japanese aesthetics via the study of prehistoric and folk art. Art critic Sawaragi Noi points out that in Okamoto’s study of the pottery of the Jōmon period (circa 12,000BCE – 300BCE),17 the artist saw Jōmon pottery not merely as the archaeological relics we see today but as the artworks (geijutsu) of their own era. He tried to smash Japanese art’s orthodox aesthetic tropes of wabi, sabi and wa (harmony), which he regarded as counterfeit traditions, and continued his research by traveling throughout the archipelago to explore the “lost Japan”. He was particularly fascinated by the artistic and festival traditions of Okinawa18 and the Tōhoku region of northeastern Japan. In the mid-twentieth-century, these regions were regarded as having little to offer in terms of art and culture but for Okamoto they were to play a central role in his development of an alternative art history of Japan.19

Okamoto had a particularly strong interest in the indigenous cultural traditions of the Japanese archipelago which preceded the coming of Buddhist culture, and he saw these earlier traditions preserved in the folk practices of regions such as Okinawa and Tōhoku. The essence of these traditions, he concluded, is that they “have no form, and do not remain”.20 His primary interest was not in artworks as artefacts but in the experience provoked by the encounter between a work and its observer. Okamoto wanted the memory of that experience to remain for a long time, even if the artwork itself was lost, and hoped that at some point the work might possess the power to change that person’s way of living. This sense of something capable of creating a transformation explains why Okamoto thought of art as a kind of “sorcery”.21

Okamoto’s deep appreciation of the magic of art as a means of provoking individual and social transformation, his experiences in Paris and his anti-war art are all reflected in the composition of what Okamoto Toshiko (1926–2005) regarded as Tarō’s greatest masterpiece: Myth of Tomorrow.22 The mural was originally commissioned by Mexican hotelier Manuel Suarez for a luxury hotel he was building in Mexico City. Okamoto worked on the mural during numerous trips to Mexico City between 1967 and 1969. Okamoto had earlier been inspired by the folk art and festival traditions of the Japanese archipelago, and he now drew on the Mexican folk tradition of the Day of the Dead festival in the composition of Myth of Tomorrow as well as Mexico’s contemporary mural painting culture. During his visits to the region in the mid-1960s to film a telemovie he had been inspired by the skeleton motifs that could be found in the festival traditions, in art and even in souvenir shops. These influences appeared in the mural’s central skeleton motif. A lover of Mexican culture, Okamoto even speculated in Bi no Juryoku23 that the similarities between Jōmon cultural relics and those from South and Central America were evidence for the existence of a pre-historic pan-Pacific cultural sphere.24

While the mural Myth of Tomorrow was completed by 1969, the Mexican hotel for which Okamoto’s mural was commissioned, originally scheduled to open in time for the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, remained incomplete. The mural was installed in the hotel lobby but the building was never completed. Suarez himself encountered financial difficulties before dying in 1987. The incomplete hotel was sold to a developer and the mural went missing. It was only rediscovered in 2003, more than thirty years later, by Okamoto Tarō’s life partner, Okamoto Toshiko, in a construction company storage yard outside Mexico City.25 Toshiko spearheaded a campaign in Japan to raise funds to purchase the mural and bring it back to Japan for restoration.26 It was finally hung in its current location in Shibuya station in 2008.27

Chim↑Pom: Making Art in Real Times

LEVEL 7 feat. “Myth of Tomorrow” by Chim↑Pom. After removal from Shibuya station. |

After Chim↑Pom’s LEVEL 7 feat. “Myth of Tomorrow” was removed from Shibuya station by police it was returned to the artists who exhibited it as part of their Real Times show alongside other works inspired by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disasters. The show was well attended, attracting an average of 500 people per day over six days.28 A press release issued by the Mujin-to Production gallery to advertise the exhibition explained that the exhibition would seek to explore the “post-3/11” era through its past, primarily through video works.29 The “Real Times” theme was described in terms of a “now à real-time” after 3/11 and a “real era/era of the real” which we refer to as “now”. The theme addressed the traces of the past which are manifest in the living present through the recognition that “now has been created by the past”. This was an exhibition about the times in which we are living right now, where the radiological disaster at Fukushima and its continually-unfolding consequences have become a part of our contemporary reality. The exhibition also puts this reality in its historical context. In the installation LEVEL 7 feat. “Myth of Tomorrow” Chim↑Pom had cleverly incorporated Okamoto’s tableau within their more recent work. Their use of the word “feature” in the work’s title situates the past depicted in Okamoto’s work within the present moment. Today’s Real Times are both new, modern times but they are also times which are shaped by the unresolved contradictions of the past. Notions of “post-disaster”, like that of the “post-war” which is ever-present in Japanese art and political discourse, are not fixed periods of time.30 By naming these periods of time we are not recognising a pre-existing reality but rather engaging in ongoing struggles over how to define and delimit the past. This affects how we produce the present. Chim↑Pom’s actions imply that the contested history of nuclear technologies is very much a part of our own times “after Fukushima”. By including their panel strategically next to Okamoto’s own reference to an event which contributed to the development of Japan’s anti-nuclear movement, the Lucky Dragon incident, the Chim↑Pom group prompts viewers to remember that their own artistic activism is part of a long history of anti-nuclear struggle.

The titular work of the exhibition, Real Times, was a video work in which the group carried out another legally dubious installation, this time in the restricted zone around the Fukushima nuclear power plant. In the video the group are shown unfurling a white flag at a lookout point within the power plant site. One member proceeds to spray a red circle on the flag – transforming it into the Japanese national flag – before painting three trapezoidal shapes around the edge of the circle. It now becomes the universal symbol for radioactivity, but painted in Japan’s national colours.31 The work thereby suggests a connection between the myth of safety (anzen shinwa) and the mythology of the nation-state. Works such as this adopted an activist stance towards the nuclear disaster and exposed the “hidden reality” of nuclear disaster which lay behind the meek repetitions in the mainstream media of official government sources which downplayed the seriousness of the event.32

For commentators such as zainichi Korean intellectual Suh Kyungsik, the imbrication of the events surrounding the Fukushima nuclear disaster with the unresolved conflicts of the post-war means that after Fukushima we are not turning “a new page” in history but rather that “the page which cannot be turned is once again exposed”.33 Suh points to the rarely-acknowledged fact that Japan’s nuclear reactors and the wastes (such as plutonium) which they produce are not simple the product of an industrial policy engineered to guarantee Japan’s economic prosperity. They are also a means of maintaining nuclear weapons potential and producing the fissile materials which could be used in nuclear weapons.34 Philosopher Karatani Kōjin has pointed out that the amendment of Japan’s Atomic Energy Basic Law (Genshiryoku Kihon Hō) in June 2012 to include “contribution to our national security” among the aims of nuclear power35 suggests that “the true motive for the restart [of the nuclear reactors which went offline after Fukushima] lies in ‘nuclear weapons'”.36 Chim↑Pom’s juxtaposition of the smouldering reactors at Fukushima and Okamoto’s atomic tableau suggests an understanding of the nuclear problem as inseparable from Japan’s security relationship with the United States, a relationship originating in Japan’s defeat in 1945, its occupation by a U.S.-dominated military force and its location under the U.S. “nuclear umbrella”.

Chim↑Pom’s work explores our “real times” by visualising these hidden traces of the past. Writing about LEVEL 7, the group note that the existence of a gap in the lower right-hand corner of Myth of Tomorrow, into which their own PVC sheet was fixed, was itself an accident of history. This gap, which gives the appearance that the bottom portion of the two end panels of the mural are missing, actually exists because the mural was designed to fit into a particular space in the lobby of the never-completed Hotel de Mexico. Though left empty accidentally this space provided, the group write, a “prophetic blank for the 21st century”. They completed this “gap” in the mural with a work that depicted the reality faced by people in Japan, and indeed all over the world, who are living in in the aftermath of Fukushima.37 LEVEL 7 feat. “Myth of Tomorrow” incorporates the larger work, the “before”, into our Real Times. Chim↑Pom remind us that even though their panel has been removed from the wall in the corridors of Shibuya’s sprawling central station, we can still perceive its presence through our imagination. The group write that “to see the work [LEVEL 7] through its absence must require our imagination instead of eyes, just as to conceive history or radiation”.38 I had to practice this act of “seeing with the imagination” myself as I returned again and again to Shibuya station to gaze upon the mural while developing the ideas in this article. It is precisely this power of “seeing through absence” that we must cultivate in order to recognise the invisible traces of radiation left by the bombing of Hiroshima, the Bravo tests which contaminated the Marshall Islands and the Lucky Dragon, and the reactor explosions at Fukushima.

Myths of Tomorrow: Progressivism, Science and the Osaka 1970 World Fair

Chim↑Pom’s intervention alongside Myth of Tomorrow occurred exactly one hundred years after Okamoto was born.39 A number of commemorative events were organised for the centenary of the artist’s birth such as the exhibition “Okamoto Tarō –The 100th Anniversary of His Birth” at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Art critic Sawaragi Noi writes of his discomfort regarding this exhibition, the first major exhibition of Okamoto’s work in this “national”, state-sanctioned art gallery. He notes that Okamoto held the official art world in disdain. Does not the holding of such an exhibition at a prestigious state-sponsored art gallery therefore mean, Sawaragi asks, that Okamoto has now been re-incorporated into this very world? Nevertheless, as Sawaragi goes on to explore, the artist had his own contradictory relationship with institutions of state power during his lifetime.40

Okamoto completed Myth of Tomorrow during one of the busiest and most controversial periods of his life when he was working as theme producer for the Osaka World Fair.41 The World Fair split the avant-garde with many leading artists taking part while others affiliated with the anti-expo group (hanpaku) criticised the state-sponsored spectacle.42 Okamoto argued that he could best articulate a critique of the Expo slogan “the progress and harmony of mankind” (jinrui no shimpo to chōwa) from within the World Fair. His Tower of the Sun, an enormous sculpture constructed in the centre of the theme pavilion he was responsible for producing, was nearly 70 metres tall. The structure was so tall that it required a large hole to be cut in the centre of the roof to accommodate it. In this way Okamoto tried to disrupt the “progressive” logic of the pavilion which he saw represented in the soaring roof of the pavilion. His Tower of the Sun proposed an alternative vision of “life” as the primitive energy of humanity which is neither progressive nor harmonious. 43

Tower of the Sun by Okamoto Tarō. |

While Okamoto may have felt he could best articulate his own critique of technological progressivism from within the expo, the technological and artistic spectacle of the World Fair marked, Chim↑Pom point out, the symbolic beginning of the “Nuclear Power Era” (genpatsu gannen). The expo was powered, to great fanfare, using nuclear power, known at the time as the “energy of dreams”,44 sourced from Japan’s first two commercial light water reactors which had recently been completed at Mihama and Tsuruga in Fukui Prefecture.45 The Fair took place in 1970, the year the U.S.–Japan security treaty (Anpo) was to be renewed – ten years after the first Anpo struggle of 1960. In 1960, millions had taken part in protests against the ratification of the treaty by the Japanese Diet. In 1970, however, only small, mostly student protests took place. The issue of the security treaty had faded as the spectacular high economic growth of the 1960s lifted millions out of poverty and created a mass-consumer society. Nevertheless, while the Security Treaty may have faded from the public eye, Yoshimi Shun’ya points out that the growth of heavy industry and the development of nuclear power generation technologies in Japan were inseparable from a Cold War regime characterised by military and economic dependence on the United States. It was no accident that the nuclear energy which powered the World Fair’s celebration of the achievements of the high growth economy was sourced from reactors constructed by joint consortia between Japanese electric power companies and U.S. manufacturers such as General Electric and Westinghouse.46

Sawaragi Noi suggests that we need to consider Myth of Tomorrow alongside Okamoto’s Tower of the Sun in order to understand the artist’s own “myth of tomorrow”. The mural contrasts the ability of atomic energy to “secure” the future with the original life-energy of humanity, which Okamoto saw preserved in ritual practices such as those he had observed in Okinawa and Tōhoku. While for Okamoto the technological threat was not nuclear power but nuclear war, Sawaragi argues that from today’s perspective we can re-read the fundamental opposition between humanity and technology as an opposition between human life energy and nuclear power.47 If humanity has a future, Okamoto proposed, it is not to be found in blind faith in the development of technology but in the original life-energy which is revealed in myth.48 The “prosperous post-war” (yutaka na sengo) which was celebrated at the Osaka World Fair depended on this electricity to power both heavy industry and the expanding consumerist lifestyle in Japan’s cities. We can not, Yoshimi observes, separate “atoms for peace” from the dream of electric-powered economic growth. In the face of the broad-based support for a “peaceful” and “prosperous” post-war lifestyle, the structural inequities of the U.S.–Japan alliance, founded on the destruction of Hiroshima, disappeared from view behind the “dream” of nuclear energy.49

Chim↑Pom’s LEVEL 7 reminds us that before the “peaceful use” of nuclear fission for fuelling the post-war dream of economic progress, Japan had already experienced the dreadful power of the atom at the hands of the U.S. military. The artists’ intervention beside Okamoto’s mural enables us to re-read the mural not only as an historical relic of post-war art with its concern with Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Lucky Dragon but as a contemporary work which is still relevant to the “post-3/11” world. As Sawaragi Noi observes, Chim↑Pom’s intervention has rescued the celebrations of the centenary of Okamoto Tarō’s birth in 2011 from becoming a simplistic “recollection and mythologising” of Okamoto Tarō. Their work has made his challenge a part of our times.50

Conclusion

Chim↑Pom’s intervention in the midst of what is both literally and figuratively a pedestrian space within a commuter corridor of a major railway station suggests that it is in the everyday that we make Real Times. Commuters could walk past the installation, as many did, without even noticing it. Or, as one person did on 2 May 2011, they could notify the authorities and have this uncomfortable visual trace of the Fukushima nuclear disaster removed, affirming Okamoto Tarō’s canonical status and reducing the threat that his work and his memory might still pose to the status quo. The memory of LEVEL 7, however, like the radioactive traces it depicts, will be with us forever. Chim↑Pom invite us not to look away from the discomfort of history. Their intervention in the lower-right hand corner of Myth of Tomorrow, in a gap which was left by an accident of history, invites us to imagine our own ability to intervene in the “blank spaces” left by history. They invite a historical truthfulness51 but also what amounts to a revolutionary praxis whereby we might construct different futures which are accountable to the past but are no longer bound to repeat it.

Chim↑Pom’s guerrilla installation skilfully utilised this large, prominently-displayed and well-known mural by a famous avant-garde artist to place the events of March 2011 into a larger historical context, thereby connecting nuclear power generation with its origins in nuclear war. By installing their own panel alongside a piece of public art, the artists invited viewers to reflect on the events at Fukushima in the context of their collective memories of nuclear devastation and nuclear-fuelled economic growth which have defined post-war Japan. LEVEL 7 connects the most recent tragedy of the atomic age with the bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. Its suggestive positioning below the Lucky Dragon invites contemporary activists to continue in the tradition of anti-nuclear struggle which has been such an important part of Japan’s post-war experience.

As Japanese society confronts its fourth major radiological incident the struggle over what kind of modernity Japan should pursue has prompted artists such as Chim↑Pom to re-examine Okamoto’s “myth of tomorrow” – an alternative to that proposed by nuclear war and high-tech economic growth. By cleverly “featuring” Okamoto’s original mural within their representation of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster Chim↑Pom enable us to recognise the contested development of nuclear power and its imbrication in the forgetting of nuclear technology’s deadly origins. Throughout the post-war period, struggles over environmental pollution and nuclear power have called attention to the contradictions of capitalist modernity and have contributed to the development of alternative “myths of tomorrow”. Chim↑Pom’s work suggests that the struggle for a different tomorrow can only take place in the midst of these unresolved contradictions of the past.

Okamoto believed that even terrible tragedies such as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be overcome by a humanity which refused to give in to despair.52 Chim↑Pom’s work likewise demands that we respond to Fukushima not with despair but by recognising the possibilities which emerge from tragedy. The disaster has brought about a rejuvenation of Japanese civil society and popular protest. This points to just the kind of “possibility” which Chim↑Pom see as the product of the imagination, something art is uniquely situated to provoke and reflect. Chim↑Pom’s installation alongside Okamoto Tarō’s mural produces a temporality which responds to but is not bound by the past. It spurs the power of the imagination to produce new futures. This seems closest to the artists’ own intentions, when they write,

we believe imagination is the very possibility for ground zero,

and the most fundamental power to create the future.

And we believe art exists as such.53

Notes

1 “LEVEL 7 feat. Myth of Tomorrow“, 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

2 “Okamoto Tarō san no Hekiga ni Itazura” [Okamoto Tarō’s Mural Vandalised], Asahi Shimbun, Evening edition, 2 May 2011, p.10; Chūnichi supōtsu, 2 May 2011.

3 Nishioka Kazumasa, “Okamoto Tarō Hekiga ni Genpatsu no e Tsuketashi, Sawagase Shūdan, Jitsu wa Shitataka” [Agitators Who Added a Painting of a Nuclear Power Plant to Okamoto Tarō’s Mural are Really Determined], Asahi Shimbun, Morning edition, 25 May 2011, p. 25; Chim↑Pom, Geijutsu Jikkō Han Art Perpetrators], Tokyo, Asahi Shuppansha, 2012, p. 10.

4 Aida has also tackled political themes, such as in his War Picture Returns series.

5 Edan Corkill, “Shock tactics return”, Japan Times. Retrieved 12 March 2013; Christopher Y. Lew, “Foreword” in Super Rat, Tokyo, PARCO, 2012, pp. 12–15 (p. 15); “The trashy art of Asian diplomacy”, Japan Times. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

6 The Level 7 in the title refers to the level assigned to the Fukushima nuclear disaster on the International Nuclear Event Scale, the International Atomic Energy Agency’s measure of the severity of nuclear accidents. The Japanese government raised their assessment of the severity of the disaster from an initial rating of 5 (equivalent to the Three Mile Island accident of 1979) to 7 (the same level given to the Chernobyl disaster of 1986) after the country’s nuclear safety commission revealed that the amount of radioactive materials released from the damaged reactors had reached 10,000 terabecquerels per hour for several hours after the March accident.

7 Yoshimi Shun’ya, Yume no Genshiryoku [Atoms for Dream], Tokyo, Chikuma Shobō, 2014, p. 23–26.

8 Carl Cassegård, “Japan’s Lost Decade and its Two Recoveries: On Sawaragi Noi, Japanese Neo-pop and Anti-war Activism” in Nina Cornyetz and J. Keith Vincent (eds.) Perversion and Modern Japan: Psychoanalysis, Literature, Culture, Routledge, 2009, pp. 48–52.

9 Sawaragi Noi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu: Kitaru beki Okamoto Tarō e Tarō and Explosion: To an Okamoto Tarō Yet to Come], Tokyo, Kawade Shobō Shinsha, 2012, p. 44.

10 Yuhara Kimihiro (ed), Okamoto Tarō Shin Seiki A New Century of Okamoto Tarō], Bessatsu Taiyō: Nihon No Kokoro [Taiyō Supplement: The Soul of Japan], no. 179, Tokyo, Heibonsha, 2011, p. 22.

11 The London Naval Conference of 1930 was the third in a series of five meetings to determine limitations on the naval capacity of the world’s largest naval powers in the wake of the First World War. Japan participated in the conferences alongside Great Britain, the United States, Japan, France and Italy.

12 Yuhara, Okamoto Tarō, p. 36.

13 Ōsugi Hiroshi, “‘Asu no Shinwa’ Kansei ni itaru Hansen, Hankaku no Messēji [Anti-war and Anti-nuclear Messages in the Lead up to Myth of Tomorrow]’ in Asu no shinwa: Okamoto Tarō no Messēji, 2006, p. 80.

14 Aya Homei, “The contentious death of Mr Kuboyama: science as politics in the 1954 Lucky Dragon incident”, Japan Forum, vol. 25, no. 2, 2013, p. 213. Ann Sherif has pointed out that although the Lucky Dragon incident is widely credited with sparking an anti-atomic bomb movement in Japan such a movement did already exist. Prior to the Lucky Dragon incident, however, the movement was primarily led by supporters of the Japan Communist Party, Japan Socialist Party and the labour unions. Following the incident, however, the involvement of large numbers of non-aligned citizens, particularly the famous homemakers of Suginami ward in Tokyo who led the “Ban the Bomb” petition movement, made the movement more palatable to media representation in the deeply polarised environment of the Cold War. See Ann Sherif, “Thermonuclear weapons and tuna: testing, protest and knowledge in Japan”, in Jadwiga E. Pieper Mooney and Fabio Lanza (eds.), Decentering Cold War History, Routledge, Oxon, 2013, pp. 15–30.

15 Ōsugi, “‘Asu no Shinwa'”, p. 80.

16 Okamoto Tarō, Jujutsu Tanjō The Birth of Sorcery], Tokyo, Misuzu Shobō, 1998, p. 32.

17 Okamoto Tarō, Nihon no Dentō [Japan’s Traditions], Tokyo, Misuzu Shobō, 1999.

18 Okamoto Tarō, Okinawa Bunka Ron: Wasurerareta Nihon On Okinawan Culture: The Forgotten Japan], Tokyo, Chūo Kōronsha, 1996.

19 Sawaragi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu, p. 20.

20 Sawaragi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu, pp. 31–32.

21 Sawaragi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu, p. 32.

22 Asu no Shinwa Saisei Purojekuto (ed.), Asu no Shinwa: Okamoto Tarō no Messēji, p. 4.

23 Okamoto Tarō, Bi no Juryoku The Magical Power of Art], Tokyo, Shinchōsha, 2004.

24 Yamashita Yūji, ‘Okamoto Tarō ga “Asu no shinwa” ni Kometa Omoi’ [The Feelings in Okamoto Tarō’s Myth of Tomorrow], in Asu no Shinwa: Okamoto Tarō no Messēji, 2006, pp. 69–70.

25 Okamoto Toshiko, “Asu no Shinwa Hakken”, p. 4

26 The restoration process is chronicled in Yoshimura Emiiryū, Okamoto Tarō “Asu no Shinwa” shūfuku 960 nichi kan no kiroku A Record of 960 Days Restoring Okamoto Tarō’s “Myth of Tomorrow”, Tokyo, Puraimu, 2006.

27 Coco Masters, “A Lost Masterpiece, Now Found in Tokyo’s Metro”, Time, 18 November 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

28 Edan Corkill, “Chim↑Pom and the Art of Social Engagement”, Japan Times Online, 29 September 2011. Retreived 12 March 2013.

29 “Mujin-to Production”. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

30 For an exploration of the politics of the seemingly unending “post-war” see Harry D. Harootunian, “Japan’s Long Postwar: The Trick of Memory and the Ruse of History”, South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 99, no. 4, pp. 715–739.

31 Chim↑Pom, SUPER RAT, Tokyo, Paruko Entateinmento Jigyōbu, 2012, pp. 24–26.

32 Atsuro Morita, Anders Blok and Shuhei Kimura, “Environmental Infrastructures of Emergency: The Formation of a Civic Radiation Monitoring Map during the Fukushima Disaster”, in Richard Hindmarsh (ed.), Nuclear Disaster at Fukushima Daiichi: Social, Political and Environmental Issues, London, Routledge, 2013, p. 81–84. See also David McNeill, “Truth to Power: Japanese Media, International Media and 3.11 Reportage”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 11, iss. 10, no. 3, 11 March 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

33 Suh Kyungsik, “‘Igo’ ni arawareru ‘izen’ [The “Before” That Appears in the “After”]”, in Hihyō Kenkyū Critical Inquiry], vol. 1, 2012, p. 6. This and all subsequent translations are my own unless otherwise noted.

34 Suh, “‘Igo’ ni arawareru ‘izen'”, pp. 6–7.

35 “Genshiryoku Kiseiihō, Mokuteki ni, “Anzen Hoshō” Genshiryoku Kihonhō ni mo Tsuika [‘National Security’ Added to the Objectives of the Nuclear Regulation Authority Law, Same Change Made to the Atomic Energy Basic Law], Asahi Shimbun, 21 June 2012.

36 ‘Press Release (English)’. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

37 Chim↑Pom, SUPER RAT, p. 31.

38 Chim↑Pom, SUPER RAT, p. 31. Translation in original.

39 Chim↑Pom, Geijutsu jikkōhan, p. 12.

40 Sawaragi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu, p. 12–13.

41 Okamoto Toshiko, “‘Asu no Shinwa’ Hakken [The Discovery of Myth of Tomorrow]” in Asu no Shinwa Saisei Purojekuto (ed.) Asu no Shinwa: Okamoto Tarō no Messēji The Myth of Tomorrow: Okamoto Tarō’s Message], Tokyo, Seishun Shuppansha, 2006, p. 4.

42 Cassegård, “Japan’s Lost Decade and its Two Recoveries”, 48.

43 Cassegård, “Japan’s Lost Decade and its Two Recoveries”, 48–51.

44 Chim↑Pom, Geijutsu Jikkō Han, p. 11; Yoshimi, Yume no Genshiryoku.

45 The Japan Atomic Power Company Tōkai Daiichi nuclear reactor, which was based on a British Calder Hall type reactor, had been completed four years earlier at Tōkai-mura in Ibaraki prefecture but the technology was inefficient and expensive and all new reactors built during the 1970s were of the American light water type.

46 Yoshimi, Yume no Genshiryoku, pp. 14–15.

47 Sawaragi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu, p. 300.

48 Sawaragi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu, p. 299.

49 Yoshimi, Yume no Genshiryoku, pp. 39–42.

50 Sawaragi, Tarō to Bakuhatsu, p. 301.

51 Tessa Morris-Suzuki, The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History, New York, Verso, 2004, pp. 229–244.

52 Okamoto Toshiko, “‘Asu no Shinwa’ Hakken”, p. 10.

53 Chim↑Pom, SUPER RAT, p. 31. Translation in original.