Abstract: This paper explores the politics surrounding the dismantling of the ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral. It shows how U.S-Japan relations in the mid-1950s shaped the 1958 decision by the Catholic community of Urakami to dismantle and subsequently to reconstruct the ruins. The paper also assesses the significance of the struggle over the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral for understanding the respective responses to atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It further casts new light on the wartime role of the Catholic Church and of Nagai Takashi.

Keywords: Nagasaki, Atomic Bomb, Urakami Cathedral, the People-to-People program, Lucky Dragon # 5 incident, Japanese antinuclear movement, the peaceful use of nuclear energy, sister city relation between Nagasaki and St. Paul, U.S.-Japan Security Alliance.

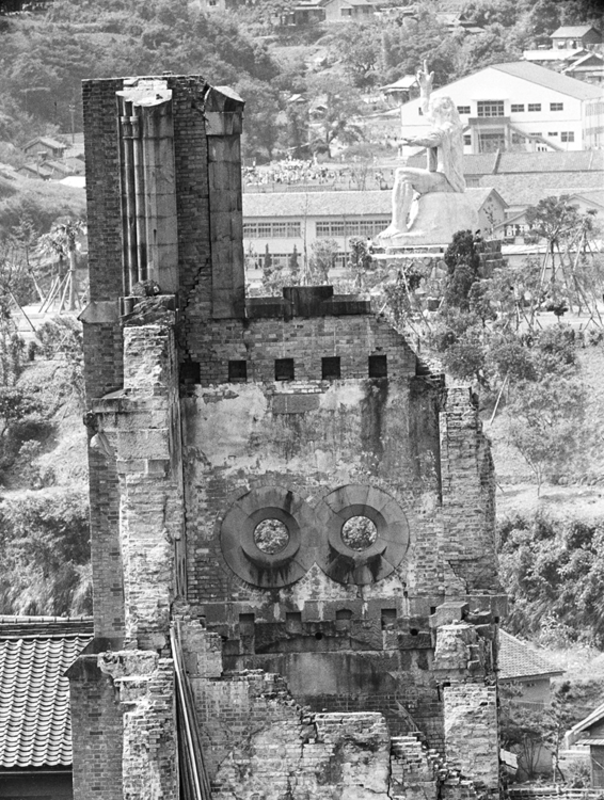

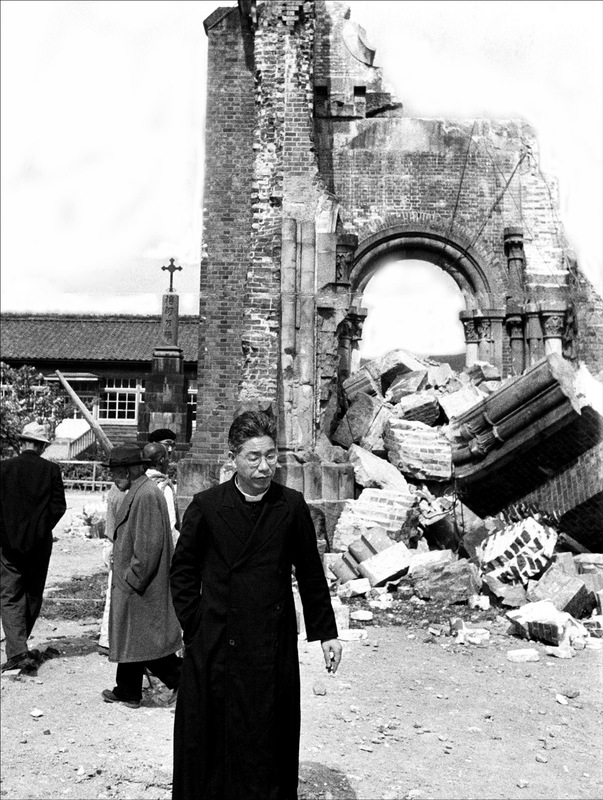

The two photographs below depict the remnants of the Urakami Cathedral following the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Both were taken in 1953 by Takahara Itaru, a former Mainichi Shimbun photographer as well as a Nagasaki hibakusha. Most of the children playing beside the ruins were born after the atomic bombing and grew up in Urakami’s atomic field. Takahara’s photographs capture the remnants of the cathedral in shaping the postwar landscape and lives of people in and around Urakami.1

|

|

|

Remnants of the Southern Wall and statues of the saints of Urakami Cathedral Photo courtesy of Takahara Itaru |

Children play in remnants of belfry of Urakami Cathedral Photo Courtesy of Takahara Itaru |

The Urakami Cathedral was inaugurated in 1914 and completed in 1925 with the installation of the twin belfries. But events leading to its construction date back to the late nineteenth century. Christianity was outlawed by the Japanese government from the seventeenth century to the late nineteenth century. In 1873, when the Meiji government lifted the ban on Christianity, approximately 1,900 Urakami Catholic villagers, who had survived exile and persecution, returned to Urakami. In June 1880, they purchased land from the village headman and converted a house into a temporary church. The property had been the site of the memory of the Urakami Catholics’ martyrdom; it was exactly the site where their ancestors were ordered to trample on Christian images (the practice was called ‘fumi-e’) in order to demonstrate renunciation of Christianity to the feudal authorities. This was also the site where many of their ancestors refused to renounce their faith in the face of the torture and death.2 In 1895, about 5,000 Urakami Catholics decided to construct a cathedral. According to the oral history of the Urakami Catholic community, the construction of the cathedral was paid for by a tithe in which each parishioner donated a portion of their scant wages. Many of them went to town to sell vegetables, and purchase bricks on their way back with the money they had earned. They also physically contributed to the construction by manually carving stones and laying bricks. It took thirty years to complete the Romanesque cathedral. Every corner was adorned with carvings and statues of Christ, Mary, and the saints. The Urakami Catholics believed that the cathedral symbolized retribution for four centuries of faith and sacrifice. It was the grandest church in the Far East.3

On August 9, 1945, twenty-four Urakami Catholics were preparing to celebrate the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, and Father Tamaya Fusayoshi was hearing confession. At the same time, the American B-29 bomber “Bockscar” was redirected from Kokura to Nagasaki due to haze and smoke obscuring the target site of the large ammunition arsenal in the city of Kokura. None of the twenty-five people in the cathedral survived the bomb explosion. In March 1958, the remnants of the cathedral were demolished. In 1959, the Urakami Cathedral was completely reconstructed, leaving no trace of the destruction of the original cathedral or the demolition of its remnants. Only photographs remain to testify to its destruction.

While many older residents remember the dismantling of the ruins as an ‘unfortunate’ event, younger residents were generally oblivious of the existence of the ruins until 2000 when Nagasaki Broadcasting Company (NBC), a private media corporation, produced a documentary entitled “God and the Atomic Bomb – The Past 55 Years of the Urakami Catholic Hibakusha” (神と原爆―浦上カトリックの55年). NBC’s documentary depicts how the General Headquarters of U.S. occupation (GHQ) decided to permit the publication of The Bells of Nagasaki written by Nagai Takashi, Urakami’s Catholic doctor and atomic bomb victim, in 1949, and how Nagai’s biblical interpretation of Nagasaki’s atomic bombing as “divine providence” and his biblical narrative of “forgiveness,” “reconciliation” and “prayers” have shaped the historical consciousness of Urakami Catholic atomic bomb survivors over subsequent decades. In one of scene in the documentary, a female Urakami Catholic hibakusha quietly watches the local TV news report on a U.S. nuclear test. The viewer sees only her face and her gaze turning towards the TV screen as an anchor reports that the purpose of the nuclear test was to examine the “safety” and “reliability” of U.S. nuclear weapons. Her face, half of which is covered by a keloid, seems impassive. But she bites her lip as if holding back tears. After the news, she offers a prayer. Then, she says:

I did have anger inside me toward America. But all I could do was seek the support of God and pray to him to keep me alive another day and give me the strength to survive tomorrow. I am still angry, but there is nothing I can do. I can’t join a movement or cry out in protest. All we can do as part of our [Catholic] teaching is to pray for peace. That is all we can do in our position, no matter how angry we may be.4

The documentary records how Nagasaki mayor, Tagawa Tsutomu, who had previously favoured preservation of the ruins of the cathedral, changed his position following a 1956 trip to the United States. The official purpose of Tagawa’s trip was to visit Nagasaki’s sister city, St. Paul. The sister city agreement was signed on December 7, 1955, the day commemorating the attack on Pearl Harbour. The documentary also discloses that Bishop Yamaguchi Aijiro, an influential figure in the Nagasaki Catholic community who was also invited by an American Catholic institution to the United States in 1955, determined to dismantle the ruins upon his return. During one scene of “God and the Atomic Bomb,” an interview is conducted with Nakajima Banri, an Urakami priest who, in response to the question of why the Urakami Catholic community agreed to the dismantling of the ruins, reluctantly said, “there were some external forces from the United States and international politics …” 5 Nakajima also mumbled that, “the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan was also concerned… because the Urakami Cathedral was damaged by the United States…”6 Similarly, Ikematsu Tsuneoki, a former Nagasaki city official and the first chief curator of the Nagasaki International Cultural Hall (The predecessor of today’s Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum), told a close friend that “preservation of the ruins [of the cathedral] would have caused some problem for the United States”.7 Consequently, a considerable sum of money was donated from the United States to the Nagasaki Catholic Church to reconstruct the Urakami Cathedral on condition that the ruins be dismantled. Ikematsu, however, never revealed where the money came from because, he said, “those who are involved in the politics are still alive”.8

In 2009, Takase Tsuyoshi, a journalist and second generation Nagasaki atomic bomb survivor, published a book entitled Nagasaki: Another Atomic Bomb Dome Lost (ナガサキ—消えたもうひとつの原爆ドーム). Takase conducted archival research in the United States and Japan to find out whom Tagawa had met during his 1956 trip, and if, and how those he met had persuaded Tagawa to dismantle the ruins. He traced the role of the United States Information Agency (USIA) in the sister city project, and shows that St. Paul officials had drafted an agreement for sister city relations to be signed by Mayor Tagawa on his scheduled (but postponed) trip to the city on December 7th, 1955, the fourteenth anniversary of the Pearl Harbor Attack. Takase concludes that the purpose of the sister city relationship was to symbolize the mutual forgiveness and reconciliation between the United States and Japan, and that the ruins were dismantled as a symbolic gesture of Nagasaki’s commitment to move toward a more peaceful future by forgetting the tragedy. One retired Nagasaki official I interviewed in August 2010 acknowledged that city workers had been aware of the role that politics played in dismantling the ruins of Urakami, but added that discussion of the topic had remained ‘taboo’ among them.9

Takase was the first to catalogue the evidence of U.S. involvement in Nagasaki’s decision to dismantle the ruins. However, some questions have not yet been fully answered. For instance, why did the United States seek a symbolic gesture of reconciliation between Japan and the United States centered on the atomic bombing in the mid-1950s? What role did the Nagasaki and Japanese governments play in the politics of dismantling the Urakami Cathedral ruins and shaping remembrance/oblivion of the atomic bomb memory? What accounts for the very different action of Hiroshima in the preservation of the Atomic Dome, and with what consequences?

This article examines the politics surrounding the dismantling of the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral in the face of strong opposition among the residents of Nagasaki and the atomic bomb survivors, the ‘hibakusha.’ It then explores the different outcome of the two atomic bomb ruins— Hiroshima’s Atomic Dome and Urakami Cathedral—and reflects on the significance of the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral.

Debating the Fate of the Cathedral Ruins (1949-1956)

In April 1949, Ohashi Hiroshi, the mayor of Nagasaki, established the Committee for the Preservation of the Remains of the Atomic Bombing (原爆遺構保存委員会) as a municipal advisory body. From April 1949 to March 1958, the committee held twenty-seven meetings, nine of which were dedicated to the fate of the cathedral ruins. In all nine meetings, the committee members voted in favour of preserving the ruins.10

On September 1st, 1951, an article in the Nagasaki Nichi-Nichi Shinbun asked: “Should Urakami Cathedral Be Preserved?” and included a comment by Ishida Hisashi, chair of the Committee for the Preservation of the Remains of the Atomic Bombing:

I believe that for the sake of both tourism and peace, Nagasaki city should preserve the cathedral as a work of art and as a testimonial to the atomic bombing. If it is demolished, what does Nagasaki intend to preserve as a reminder of the bombing? If a decision is made to remake everything anew without preserving the ruins, it will prove that Nagasaki has deliberately forgotten the reasons for its special designation as an international cultural city.11

This was the sentiment of the council and many Nagasaki hibakusha and residents.

However, Nagasaki Catholic leaders called for removal of the ruins and the reconstruction of a new cathedral on the site of the ruins, emphasizing that their souls were deeply attached to that site of memory where their ancestors had endured persecution more than two hundred years earlier. On the same day that the local paper published Ishida’s comments, the Nagasaki Catholic Public Relation Committee published an article in their bi-monthly bulletin, Katorikukyô hô, stating that the remaining walls were an obstacle to reconstruction of the cathedral and had to be torn down. The article asserted that removal of the ruins would be more appropriate to cultivate the “hill of blossoming peaceful flowers” in order to “plant hearts of peace”.12 The Hill of Blossoming Flowers (花咲く丘) is actually the title of one of Nagai Takashi’s books published in 1949. Nagai, who received the first Honorary Citizen of Nagasaki award from Nagasaki City Council in 1949 as well as a National Honorary Award from the Diet in 1950, wrote in that book that the reconstruction of the cathedral was critical to revive the Catholic community and spread Christ’s love in Japan.

According to Kataoka Yakichi, a scholar on the history of Japanese Catholics, especially those in Nagasaki, Nagai called for the removal of the cathedral ruins as follows:

Every time we see such a thing (konna mono) [referring to the ruins], not only do our hearts ache, but we also do not want to show the children— who will be born in the future— traces of the crimes of our generation that waged a war that even resulted in the burning of the house of God. Rather, we want to build a peaceful and beautiful church, and make this place a hill of blossoming flowers to point the hearts of the children freely to heaven.13

In using Nagai’s discourse, the Nagasaki Catholic leaders may have sought to legitimize their policy by framing the demolition of the ruins as the will of Saint Nagai, the representative figure of postwar Nagasaki.

In 1954, to counter the powerful call by non-Catholic Nagasaki residents and hibakusha for the preservation of the Cathedral, Nagasaki Catholics formed the “The Association for the Reconstruction of the Urakami Cathedral” (浦上天主堂再建委員会), and launched a fund-raising campaign. The Association estimated that the total cost for reconstruction would be over 60million yen. They anticipated that half of that could be collected through donations from Japanese Catholic churches. In the midst of their search for the other half, Bishop Yamaguchi received an invitation to North America.

In May 1955, Yamaguchi left for a ten-month trip to the United States and Canada. The official purpose of the trip was to receive an honorary doctorate from Villanova University, a private Roman Catholic institution in the United States, for his contribution to the development of the Nagasaki Catholic community and to the spiritual recovery of Nagasaki. It is believed that Yamaguchi also hoped to use the occasion to raise additional funds for the reconstruction.14 Yamaguchi visited St. Paul, Chicago, New York, Washington D.C., New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Honolulu, Toronto, Montréal, and Québec City. The trip was exceptional given that so few Japanese nationals were permitted by their government to travel abroad before 1964. Prior to his trip to North America, Yamaguchi had noted that some European churches were reconstructed in a manner that incorporated the ruins of their previous incarnations, though he had also noted that American tourists may not appreciate the reminder of the atomic bombings preserved in those ruins.15 Whatever transpired during the trip, when Yamaguchi returned to Japan in February 1956, he met with the Nagasaki Catholic community and announced that Urakami Cathedral would be rebuilt and that the ruins had to be removed.

The debate over the fate of the cathedral ruins among Nagasaki Catholics, the city council, the Committee for the Preservation of the Remnants of the Atomic Bombing, and the non-Catholic Nagasaki citizen groups intensified after Yamaguchi’s return from North America in February 1956. The city council and the Committee received support from non-Catholic Nagasaki hibakusha, who sought to ensure that the ruins were preserved, especially after the 1955 construction of the Peace Memorial Statue, which, in their eyes, far from capturing the destructive power and traumatic experience of the bomb, conveyed a warlike, masculine image that failed to reference the disaster.16 The pro-preservation group believed that the ruins of the cathedral could best convey the destructive power of the bomb to non-hibakusha both present and future. Nonetheless, Yamaguchi told a local newspaper that he was adamant because he did not believe that the ruins represented peace. They represented instead a far too vivid link to a troubled and troubling past.17

|

Nagasaki’s Peace Memorial Statue photographed by the author |

The specific motivation for preservation of the ruins varied from one group to another. Some city officials and business leaders saw a commercial opportunity in the remnants. Nagasaki was awarded first place in the “Top 100 Tourist Destinations of Japan,” as presented by the Mainichi Shinbun in October 1950. One of the most popular tourist attractions of postwar Nagasaki was the site of the ruins of Urakami Cathedral.18 The Nagasaki Tourism Office stated that removal of the ruins of the cathedral would result in the loss of important tourism revenue.

The Tourism Office’s statement provoked Nagasaki Catholics. Some described it as “disturbing” that the ruins of the cathedral was treated as a sightseeing destination.19 Kataoka claimed that the Catholic community wanted to rebuild the cathedral as quickly as possible, and that any resistance or impediment to that reconstruction for the sake of turning their destroyed place of worship into a tourist destination was “sacrilegious”.20

However, Urakami Cathedral was not only the House of God during the Asia-Pacific War. It also served as the warehouse for the storage of rice and food for the Japanese imperial army and the primary space for Urakami Catholics’ patriotic activities.21 Urakami Bishop Urakawa Wasaburo taught that Urakami Catholics must work together with Japanese spirit to “demonstrate the faithful spirit of sacrifice that shines with eternal hope” at the Cathedral. 22 Likewise, Katorikukyō hō, the Nagasaki Catholic’s bulletin, served as the medium to communicate Nagasaki Catholic leaders’ official views to the followers even during the war period. On January 1, 1938, Bishop Yamaguchi stated in Katorikukyō hō that “The religious life of the present world represents the duty to serve divine will.” He went on to claim that, “Heaven requires violence” because one “cannot obtain the crown of eternal happiness without passing through narrow paths and roads of thorns.” Yamaguchi then called Japan’s invasion of China a “crusade”, a “holy war against communism” guided by the “righteousness of the Imperial Army.”23

While Yamaguchi published his annual New Year’s greetings, Nagai was serving as an imperial surgeon in Nanjing where the Japanese Imperial Army occupied and devastated the city from December 13, 1937 and committed atrocities against civilians and unarmed combatants over a period of six weeks. Nagai’s letter sent from the destroyed city of Nanjing to his Catholic community was published in Katorikukyō hō in January 1938. He wrote:

I respectfully wish you all a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year from the battlefield. We have greeted this year along with grave current events, but especially this year Japan will soar. This is the perfect opportunity for Japanese Christians to display that essence. As I pray for the activities of everyone on the home front, I, too, will render the duty of a warrior of Japan, and repay the kindness of the emperor”.24

Nagai returned to Nagasaki from China in March 1940 as a decorated soldier. He also received the Order of the Rising Sun for his ‘bravery’ in China, and continued to wear the military uniform hanging a long sword at his waist in the Nagasaki Medical University to demonstrate his patriotism to the Imperial Shinto State.25 The “troubling past” the remnants of the cathedral reminded Nagasaki Catholic leaders, including Nagai, was not only the atomic bombing, but also their wartime efforts.26

Meanwhile, the Committee for the Preservation of the Remnants of the Atomic Bombing believed that they ought to respect the religious convictions of the Catholic community, and tried to find an acceptable compromise. First, they proposed that the ruins be reinforced to prevent them from collapsing to eliminate any safety concerns. Secondly, they proposed that the city provide an alternative location for the building of a new cathedral. Thirdly, they proposed that the Urakami Catholic community build a new cathedral next to the ruins. However, all of these proposals were rejected. Urakami Bishop Nakajima Banri argued that the current site was too small to both build a new cathedral and preserve the ruins; secondly, he argued that the ruins were deteriorating, so that it was no longer possible to reinforce them; thirdly, he argued that, from the religious point of view, “refining the tragic appearance of the cathedral” was unacceptable.27

From his inauguration in 1951 until 1956, Nagasaki mayor Tagawa Tsutomu sought to ensure the preservation of the ruins of the cathedral, which was the will of many Nagasaki residents. A local engineer who worked for the city reconstruction project recalled that Tagawa had said the ruins would be preserved, and that Nagasaki Prefecture would have to handle this as the city administration was preoccupied with other reconstruction initiatives. The engineer went on to say that “I drew up a detailed strategy for the preservation of the ruins that were to be reinforced with concrete. The mayor seemed satisfied [with the plans]”.28

In 1955, Tagawa received a letter from William Hughes, a member of the American philanthropic group, the “Friend of the World.” Hughes proposed to formulate a sister-city relationship between Nagasaki and St. Paul. The Nagasaki city archive documents that the original proponent of the sister-city project between the two cities was Lewis W. Hill Jr., grandson of the founder of the Great Northern Railway. The archive explains that prior to the Asia-Pacific War, Hill Jr. had travelled to Nagasaki where he became fascinated with Nagasaki’s landscape and its warm-hearted residents. After the atomic bombing, Hill was convinced that Peace could be achieved through mutual understanding and the cultivation of true friendship. A local newspaper claimed that St. Paul was chosen because of its large Catholic community.29 Nagasaki was the first Japanese city to receive such an invitation from the United States. The city administration enthusiastically welcomed this offer as increasing the number of foreign tourists to the city had been one of the primary agendas for the city’s economic policy since 1949. Tagawa and Nagasaki councillors accepted the proposal.

In September 1955, Tagawa received an invitation from St. Paul to the ceremony marking the start of the sister city relationship. On September 4th, Nagasaki Nichi Nichi Shinbun reported that, “…St. Paul is very interested in the reconstruction of the Urakami Cathedral, which was baptized by the atomic bombing. It is expected that [St. Paul] will financially support that reconstruction.” On September 13th, the majority of Nagasaki’s councillors supported Tagawa’s trip to St. Paul as an important step in the cultivation of friendship between the United States and Japan.30 The city council asked the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs to issue a passport for Tagawa and permit an exchange of currency. The Japanese government, however, declined the request given its strict proscriptions against exporting currency.

The U.S. State Department and the American embassy in Tokyo, however, intervened. On November 7th, 1955, the Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs of the Far East, a branch of the State Department, sent a telegram to Tagawa supporting the visit as a contribution to friendship and mutual understanding.31

Two days later, the State Department sent a telegram to the American embassy in Tokyo. The telegram described the Japanese government’s rejection of Nagasaki’s request for permission to exchange currency as a significant obstacle to Tagawa’s attendance at the inauguration ceremony. The State Department then requested that the American embassy in Tokyo be permitted to unofficially seek to persuade Tokyo to authorize Nagasaki’s request.32 The telegram also included copies of the letter the State Department had sent to Tagawa and the note St. Paul had sent to the United States Information Agency (USIA). One month later, on December 7th, 1955, the fourteenth anniversary of the Pearl Harbour Attack, St. Paul’s city council approved its participation in the sister-city program with Nagasaki.

The State Department, the USIA and the American Embassy in Tokyo helped Tagawa to overcome all obstacles to his visit to the United States. Tagawa left Japan for the United States on August 22, 1956. St. Paul’s original proposal was to have Tagawa attend the sister city inauguration ceremony; however, the trip turned into a grand American tour. Tagawa visited St. Paul, Chicago, New York, Washington D.C., New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Hawaii during his one-month trip. Nagasaki’s municipal budget could not have covered the cost of such a tour. Most of the population in Japan was still suffering severe economic hardship through the 1950s while the hibakusha were left without any medical or financial assistance until 1957. Given fiscal constraints on the Japanese and Nagasaki municipal governments to promote and organize the tour, its funding was almost certainly provided by the U.S. government and/or private U.S funding.

The Nagasaki local newspaper reported that Tagawa had an attendant, a “Mr. Shinohara,” for the duration of his tour. The article described Shinohara as the head of the secretariat of the Association for the Construction of the Peace Memorial Statue (平和祈念像建設協会), the primary funding source for the Peace Statue. A local California newspaper, the Press-Telegram, described Shinohara in greater detail. On September 14th, 1956, the Press-Telegram identified Shinohara as “Morizō Shinohara,” and described him as Tagawa’s secretary and translator. Shinohara was described as having studied English and the Bible with an American Methodist missionary in Nagasaki from 1932 to 1934. He later received a Fulbright Scholarship to study in the United States after the war.

A Nagasaki city report published on October 10th, 1956 catalogued Tagawa’s itinerary.33 He met with mayors and visited hospitals, schools, and other municipal institutions. According to the archive, Tagawa’s visit was extensively reported in the American media and the sister city program was received positively in the United States. The report also stated that the State Department received Tagawa and organized all his activities during his stay in Washington D.C.; it did not, however, identify whom Tagawa met and where he visited.

U.S-Japan Relations (1953-1957)

In January 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower took office as President. Eisenhower quickly launched a drastic review of American nuclear policy, military strategy, foreign affairs, and overseas information programs as detailed in a report of the National Security Council (NSC) in March of 1953, during which Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles discussed how to overcome the taboo surrounding the use of atomic weapons (NSC March 1953). Eisenhower and Dulles were convinced that the most effective way to change public opinion on the use of nuclear weapons was to shift the public perception of the non-military use of nuclear energy.34 Stefan T. Possony, a consultant for the Psychological Strategy Board of the U.S. Defense Department and originator of the Star Wars strategy, explained that, “the atomic bomb will be accepted far more readily if at the same time atomic energy is being used for constructive ends”.35 To this end, Eisenhower made a speech at the United Nations General Assembly on December 8, 1953 titled, “Atoms for Peace.”

At the UN, Eisenhower proposed the establishment of an international organization for the peaceful use of atomic energy. The speech described his determination to solve “the fearful atomic dilemma” by finding in nuclear energy “the miraculous inventiveness of man” dedicated to life rather than death,36 and emphasized the U.S intention to halt the nuclear arms race by negotiating with the Soviet Union.37 To this end, the United States would “encourage world-wide investigation into the most effective peacetime uses of fissionable material” by providing its allies and third-world countries with “all the material needed for the conducting of all experiments that were appropriate.” He also stated that the United States was ready to begin negotiating with the Soviets to reduce “the potential destructive power of the world’s atomic stockpiles.” Eisenhower’s speech at the UN General Assembly inaugurated the psychological warfare campaign named “Atoms for Peace.”

On March 1, 1954, however, the United States tested a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb codenamed ‘Bravo’ on the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean.38 ‘Bravo,’ which was the most powerful weapon ever tested, caused massive radiological contamination and acute radiation syndrome on the inhabitants on the islands of Rongelap and Ailinginae located within the Bikini Atoll.39 At the time of its detonation, a Japanese fishing boat named the “Lucky Dragon #5” (Daigo Fukuryu Maru) was 85 miles away. All crew members were exposed to radiation, one of whom died of radiation poisoning on September 23rd, 1954.

Yomiuri Shinbun first reported the incident on March 16th, 1954. Panic spread across Japan over the possibility that irradiated tuna had been sold to Japanese consumers. The Japanese media broadcast images of Geiger counters showing high levels of radiation in fish and fishing boats in the central fish market in Tokyo. The term “shi no hai” (“ashes of death”) became widespread as a means of describing the danger of the fallout. Some 8,000 fishmongers and sushi shop owners protested American nuclear tests, demanding that the American government compensate them for their losses in discarding the irradiated catch. They also demanded that nuclear testing be outlawed. Two months later, the Japanese media warned the Japanese population that it should filter its drinking water after a strong radioactive rainfall as a result of the Bravo. The incident heightened public awareness of and sensitivity to the dangers of nuclear testing.

Japanese antinuclear and anti-American sentiments grew rapidly as the American government sought to minimize the damage caused by the Bravo test and attacked Japanese critics including the victims.40 Moreover, the US continued testing hydrogen bombs in the Bikini Atoll even after the Lucky Dragon #5 incident went public; consequently an ever-increasing number of Japanese fishing ships brought home irradiated fish to Japanese markets.41 Japanese antinuclear and anti-American sentiments was heightened in the unprecedented scale and evolved into the national movement that called out the total ban of the nuclear tests.

On August 6th 1955, the tenth anniversary of the atomic bombing, the first World Conference Against the Atomic and Hydrogen Bomb took place in Hiroshima. Some survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings testified about their experiences to the thirty thousand participants from all over Japan and some fifty foreign delegates from thirteen different countries in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.42 In September 1955, the conference evolved into the Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, called “Gensuikyo.” The U.S government expressed growing concern about the growing anti-nuclear movement and the role of Japanese Communists as it evolved into a national and international movement calling for the remembrance of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Bikini to emphasize Japan’s nuclear victimization.

From the end of the Asia-Pacific War, Japan’s integration into the American network of bases and alliances was pivotal to American interests in the Far East. The deployment of nuclear missiles in Japan was also an American priority in 1954.43 On May 26th, 1954, Eisenhower warned that growing antinuclear sentiment threatened to evolve into anti-Americanism on a national scale. The Lucky Dragon #5 incident inspired the U.S to provide Japan with nuclear technology for civilian applications in order to counter Japan’s antinuclear sentiment, suppress communist influence, and keep Japan within the sphere of American power.44

Eisenhower’s nuclear campaign, “Atoms for Peace,” was very attractive to Japanese capitalists and politicians given shortages of electric power. Moreover, building nuclear power plants could pave the way for Japan’s development of nuclear weapons. However, the Eisenhower administration initially excluded Japan and West Germany from its list of possible recipients of American nuclear technology because of the risk that they would develop nuclear weaponry to challenge the United States.45

Shoriki Matsutaro, a Japanese media tycoon, was one of the most prominent promoters of the benefits of the nuclear energy. Shoriki was an unindicted Class-A war criminal imprisoned for two years who was released without trial in 1947. He became the president of the Yomiuri Shinbun in 1950 and of the Japan TV Corporation in 1952. Shoriki and Yomiuri became key Japanese proponents of nuclear energy. In January 1954, two months before the Lucky Dragon #5 Incident, Shoriki’s Yomiuri Shinbun began a series of special features on nuclear energy titled, “We Have Finally Caught the Sun – Can nuclear energy make human beings happy?” (「ついに太陽を捉えたー原子力は人を幸福にするか」), which vigorously propagated Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace campaign.

Meanwhile, a group of Japanese politicians were drafting a budget for the development of Japan’s first nuclear energy program. On March 3, 1954, under the leadership of a young politician Nakasone Yasuhiro, three political parties—Liberal Party (自由党), Reform Party (改進党), Japanese Liberal Party (日本自由党)—jointly submitted the draft. The next day, Koyama Kuranosuke, one of the authors of the draft budget and Nakasone’s ally claimed:

The American President has already stated that the United States would train Japan to use a new type of weapon, and it is extremely regrettable that our government has not yet accepted this invitation… If we are to avoid inheriting America’s out-dated conventional weaponry, we must understand the mechanisms of the new weaponry and become competent in its use. Therefore, we three parties have asked the Diet to pass a budget for a nuclear energy research program that aims to create nuclear reactors and pursue the peaceful applications of nuclear energy along with the United States…46

Koyama revealed that under Nakasone’s leadership Japan would seek access to the military applications of nuclear energy by means of a non-military nuclear program. Koyama’s statement created an uproar in Japanese public opinion. On March 4, an editorial in the Asahi Shinbun called for the “removal of the draft budget” for the nuclear energy program. It severely criticized the ambiguity of the project and suggested that the project could be construed as preparation for war, a course barred by Japan’s Constitution.

The members of the Science Council of Japan (JSC) also immediately criticized Nakasone’s approach. On March 4, 1954 the Asahi Shinbun published, “Sudden advent of the draft budget for the production of nuclear reactors – Scholars oppose it as premature” That day the Mainichi Shinbun headlined, “Scholars puzzled over the abrupt appearance of the budget for the nuclear power program and call for its amendment”.

The issue of Japanese development of nuclear energy was not new. Japanese scientists had conducted research into atomic bombs after the attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941; however, when they concluded that an atomic bomb was only possible in theory, not in practice, the project was abandoned.47 Thus, the Japanese scientific community was astonished by the atomic bombs and admired the scientific success of the American nuclear fission program. During U.S. occupation, while GHQ banned Japan from engaging in nuclear research, leading Japanese scientists and the three largest newspapers, Asahi, Mainichi and Yomiuri, began to promote nuclear energy research through the dissemination of the redemptive discourse “Atoms for Dreams” that the atomic bombing was the necessary precursor to rebuilding a new, stronger, more powerful, peaceful, and prosperous Japan.48 Yukawa Hideki, the most prominent theoretical physicist in postwar Japan as well as one of the scientists in the aborted Japanese atomic bomb development project, stated in 1948:

Nuclear physicists received significant benefits from the development of the atomic bombs as it facilitates the studies of nuclear physics. As long as human beings do not make a mistake that would result in the annihilation of the entire world, science will continue to progress […] We cannot anticipate what kind of by-products can occur in the process of developing nuclear science technology. However, there is no doubt that it [nuclear energy] will enrich our lives and bring about the perpetual peace to the world […] The success of the atomic bomb explosion was the first step to realize such a dream. It will be beyond our imagination how the peaceful use of nuclear energy can contribute the welfare of the people.49

The discourse of “Atoms for Dreams” began to proliferate after Yukawa’s statement appeared in national newspapers and science journals, and reached a peak when Yukawa received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1949.50 The Japanese scientific community and print media had never opposed research on nuclear energy per se when directed toward the development of peaceful applications of nuclear energy. As Takekawa Shunichi argues, most prominent Japanese scientists and national newspapers “showed strong interest in the potential of nuclear power” and “drew a line between peaceful and military uses of nuclear power”.51 Put differently, Japanese scientists and media, regardless of political position, “embraced the dual nature of nuclear power”.52 Shoriki and Nakasone, recognizing the climate of public opinion and the position of the Japanese scientific community, modified the discourse on nuclear energy research accordingly.

On March 8, 1954 Shoriki’s Yomiuri published an article “Japan Enters the Nuclear Era,” promoting the draft budget for the nuclear energy program as a “progressive” idea. Promoters of nuclear energy research became more assertive. They again called on the memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as reason to promote Japan’s nuclear energy research. For instance, Taketani Mitsuo argued that, “the casualties of atomic war are entitled to have the strongest say in the development of atomic power… [Japan] has the best moral grounds to conduct research. Other nations are obliged to help Japan”. 53 On March 11, the Japan Science Council (JSC) announced that it would endorse the draft budget if nuclear energy research were directed exclusively towards civilian applications.54 The JSC’s shift in position towards nuclear energy research resulted from agreement between the JSC and Nakasone, the strongest political proponent of nuclear energy, that Upper House approval of the budget would respect their condition and provide them with significant research funds for JSC.55

On March 12, the Asahi reported that the “Science Council of Japan has endorsed the program”. On March 13, The Mainichi’s editorial stated that the draft budget had changed the objective of nuclear energy research from the “creation of nuclear reactors” to the “development of peaceful applications of nuclear energy.” The Mainichi editorial concluded that Japan could expect positive results from nuclear energy research.

The public debates over Japan’s nuclear energy program took place while the radiated Lucky Dragon # 5 was silently heading back to Japan from Bikini. On April 3rd, the Diet passed the budget, including the first nuclear energy program in the midst of the panic followed by the Lucky Dragon #5 incident. In his study on the role of the Japanese print media in the knowledge production of nuclear energy, Takekawa concludes that “…the three major newspapers argued against the military use of nuclear power, but did not oppose its peaceful uses while observing the Lucky Dragon #5 Incident and the rise of anti-nuclear sentiment and movement in Japan…[even] when the dark side of nuclear power was highlighted in Japan”.56

The USIA cooperated with Shoriki’s Yomiuri Shinbun to host exhibitions on the peaceful applications of nuclear energy in eleven major cities in Japan. The Yomiuri Shinbun reported that Japanese visitors praised the exhibition’s promotion of the civil applications of this new powerful, clean, and boundless energy source. Positive coverage of the exhibitions were disseminated throughout Japan by national and local media outlets.57

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum was selected as one of eleven sites of the exhibition in May 1956. The City Council, Hiroshima Prefectural Government, Hiroshima University, and Chugoku Shinbun enthusiastically welcomed the exhibition and co-sponsored it. Prior to the exhibition, Hamai Shinzo, the mayor of Hiroshima, even advocated construction of the first nuclear reactor in Hiroshima, stating that “the souls of the dead would be comforted should Hiroshima become the ‘first nuclear powered city.’ The citizens, I believe, would like to see death replaced by life”.58 Six members of the Association of Young Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Survivors attended the Hiroshima exhibition. The Chugoku Shinbun explained that the exhibition helped to understand that nuclear energy could positively contribute to civilization. The Atoms for Peace campaign reinforced the view that the peaceful use of nuclear energy was completely different from military use for nuclear weapons.

Nagasaki was not included in the list of nuclear energy exhibition site cities. At this time, however, USIA was coordinating a sister city program between Nagasaki and St. Paul in parallel.

Sister City Program and Eisenhower’s Global Expansion Policy

In the aftermath of World War II, William Benton, the American Assistant Secretary of State observed that diplomacy was no longer only between governments as “people of the world are exercising an ever larger influence upon decisions of foreign policy”.59 In 1946, the American military initiated its “exchange of persons program.” A number of foreign nationals received grants to come to the United States for study, research, teaching, lecturing, and observation.60 At the same time, American citizens were encouraged to go abroad to achieve similar ends. This collaborative effort of the American government and private American organizations in the service of U.S foreign policy was the centerpiece of what came to be called “U.S cultural diplomacy”.61 The program was transferred to the State Department in 1952.

The Eisenhower administration expanded U.S Cold War strategy and cultural diplomacy through military and economic integration of its allies and decolonized countries through new people’s exchange programs.62 The Eisenhower administration established the USIA in 1953 as an agency devoted to U.S cultural diplomacy and launched the “People-to-People program” to integrate other countries into U.S military, political and economic policies.

The Eisenhower administration assigned the USIA a role as the primary coordinator of the People-to-People program. The USIA Office of Private Cooperation selected American citizens to serve as members of the People-to-People program committee. The majority were well-known entrepreneurs who “had the most to gain from the integration” of the target countries.63 The creation of sister city relations between American and Japanese cities was typical of activities within the People-to-People program.64

One of the major collaborators in the People-to-People program was the American airline industry. Since the end of the war, U.S government had encouraged American airlines to expand in areas considered geopolitically vital to American security.65 American airlines frequently offered free flights for foreign guests of the State Department/USIA. The Nagasaki-St. Paul sister city program exemplifies how the Eisenhower administration and private entrepreneurs collaborated to achieve their mutual interests.

Nagasaki Mayor Tagawa travelled by Northwest Airlines to the United States in August 1956. In 1947, Northwest became the first American airline to open direct flights between the United States and Japan in 1947. It was eager to attract American tourists to Japan. However, the Lucky Dragon #5 Incident of 1954 and the subsequent rise of the anti-nuclear weapons movement appeared an obstacle to their expansion. Northwest Airlines was eager to cooperate in the People-to-People program and the sister-city program between Nagasaki and St. Paul as a means of overcoming anti-American sentiment.66

Northwest Airlines Headquarters is located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, whose capital is St. Paul. The Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP) is also a primary Northwest hub. This, together with its large Catholic population, made St. Paul an ideal candidate for the first sister-city program between the United States and Japan.

Lewis Hill Jr., the initial proponent for the sister-city project between Nagasaki and St. Paul, was one of the most powerful financiers in Minnesota and a member of the Minnesota State Assembly. He had a close relationship with Northwest Airlines and was a strong Republican supporter and friend of Eisenhower.67 The program was consistent with the diplomatic goals of the Eisenhower administration while at the same time serving the commercial interests of Northwest Airlines and the Minnesota economy.

William Hughes, who initially proposed the sister city program to Tagawa, was a member of the “Friend of the World,” the American philanthropic organization. Friend of the World had been working to establish the sister-city program between the United States and Europe since the early 1950s. Hughes’s wife was a second-generation Japanese American. Hughes was known for his strong sympathy toward and attachment to Japan. Visiting Nagasaki with his wife in 1979, Hughes explained in an interview that the St. Paul city council chose the fourteenth anniversary of the Pearl Harbour Attack as the day to sign the sister-city relationship with Nagasaki as an acknowledgement of mutual wrongdoing during the Asia-Pacific War. He also stated that the sister-city relationship would be a pledge to pursue peace in the future through healing the wound caused by the war.68 This narrative of healing and reconciliation through U.S. assistance with reconstruction/restoration of what the atomic bomb destroyed was central to Japanese and American media discourses in the mid-1950s.

Politics of Healing, Forgiveness, Restoration and Reconciliation

While Bishop Yamaguchi and Mayor Tagawa were touring the United States, a group of twenty-five young female hibakusha referred to as the “Hiroshima Maidens,” were invited to the United States to undergo reconstructive plastic surgery from 1955 to 1956. Although each visit was organized by different American private organizations, the visits were planned and carried out within the framework of U.S. cultural diplomacy. The guests from the A-bombed cities stood as symbols of healing, mutual forgiveness, restoration and reconciliation in American-Japanese relations.69

The Hiroshima Maidens first appeared in the Japanese media in June 1952 after the San Francisco Treaty went into effect and Japanese sovereignty was regained in April of that year within the framework of the US-Japan alliance. Tanimoto Kiyoshi, Hiroshima based Methodist minister and founder of the Hiroshima Peace Center, and novelist Masugi Shizue organized a fundraising campaign with Japanese celebrities, artists and writers to provide reconstruction surgery for the young women dubbed Hiroshima Maidens. With donations from all over Japan, nine Hiroshima Maidens underwent reconstructive surgery in the Koishikawa clinic in Tokyo in December 1952. Their successful surgeries encouraged Masugi to extend their fundraising campaign for Nagasaki Atomic Maidens as well.70

Masugi wrote to Mayor Tagawa that the Koishikawa clinic in Tokyo would provide the reconstruction surgery for five Nagasaki Maidens and the Tokyo branch of Hiroshima Peace Center would bear the cost. Of the 25 candidates that Mayor Tagawa and medical doctors had initially selected, three young female hibakusha were eventually chosen from Nagasaki based on the degree and location of the keloids caused by the burns, their age (those deemed still ‘marriageable’), and consequently how much they would benefit from the surgery.71

On January 21, 1953, the three Nagasaki Maidens embarked for Tokyo. On the way, they stopped by the Hiroshima Station, where six Hiroshima Atomic Maidens and Tanimoto waited for them to offer flowers to the Nagasaki Maidens. On January 22, Chugoku Shinbun reported that the Atomic Maidens from Hiroshima and Nagasaki greeted each other in tears and spontaneously began to sing the song written for the Atomic Maidens entitled “Come Back to Me, My Smile” (ほほえみよかえれ) together. The lyrics, written by Sako Michiko, one of the Hiroshima Maidens, go:

Cruel destiny I carry on my back/ A lonely life I live/ The maiden’s smile has faded/ My smile, when will it return?

冷たきさだめ 身に負うて 寂しく生きる 乙女子の 頬より消えし ほほえみよ

再びいつの 日にかえる

The melody was composed by Kobayashi Kinsaku, a Class A-war criminal imprisoned for life in Sugamo Prison in Tokyo.72 Kobayashi was the senior military police officer in the Philippines during the war.73 In June 1952, Tanimoto and Masugi brought two Hiroshima Atomic Maidens to the prison to ‘console’ (imon 慰問) the war criminals. An article in the Chugoku Shinbun dated June 12, 1952 reports that Kaya Okinori, a Hiroshima native and the former Imperial Minister of Finance, offered an apology to the two maidens, saying that “I am guilty for the suffering of my fellow Hiroshima people. I wish I could console you all [Hiroshima citizens], but I am a prisoner…” Hata Shunroku, another war criminal and the former Imperial Army supremo of the Hiroshima military, also expressed his remorse to the Maidens that “It was inevitable that the former enemy targeted Hiroshima because the city was the pivot of the Imperial Army in Western Japan. Your sufferings are the result of our presence in Hiroshima.” Chugoku Shinbun continued to write that after hearing the confession from the two war criminals, one of the Hiroshima Maidens began to cry, saying that “We have never thought that you are responsible for our suffering. We came here to work with you to eliminate war.” The article ended that the tears had “gushed from their [war criminals] devilish faces.” During this visit to Sugamo prison, the Hiroshima Maidens and Tanimoto asked Kobayashi, a Christian as well as war criminal who “loved music since he was a child” and “never let go of his guitar” even during his imperial duty in the Philippines, to compose the melody for the maidens.74 In February 1953, the song was completed under Kobayashi’s songwriter name, “Kobayashi Michio.” Therefore, before going to the United States to undergo more advanced plastic surgery, the Hiroshima Maidens, who represented Japanese victimhood, already performed the symbolic role in the forgiveness and reconciliation between the Japanese military high command that represented the Japanese responsibility for the war on one hand, and the Japanese collectivized nuclear trauma on the other. In this domestic political theater of forgiveness and reconciliation, the Japanese war criminals were represented as the accountable for U.S’s use of the atomic bombs and the hibakusha’s suffering, rather than for the numerous Japanese war atrocities committed in Asia-Pacific. It can be further argued that their dramatic encounter in Sugamo prison also reconciled the dual subjectivities of the Japanese nation as the perpetrators and victims.

Nagasaki Shinbun reported on December 28, 1952 that the writer’s group in Tokyo had asked Pearl S. Buck, a Nobel Prize winning American writer, to help their efforts to provide more advanced reconstruction surgery for the Atomic Maidens in the United States. According to the Nagasaki Shinbun article, Buck contacted the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA) through the widow of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the chairman of AOA sent a letter to the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), saying that they were planning to send a group of American plastic surgeons to Hiroshima and Nagasaki for one year. On February 13, 1953, Nagasaki Shinbun reported that the news from AOA had significantly encouraged Nagasaki Atomic Maidens; and some of them cried for joy. Aoyama Takeo, the chair of the YMCA in Nagasaki, embarked on the establishment of the Nagasaki Atomic Maiden Association to host the AOA’s medical staff.75 However, the project faded away for unknown reasons.

On the other hand, Tanimoto arranged for Norma Cousins, editor of the Saturday Review and an antinuclear activist, to meet with the Hiroshima Maidens at his church in Hiroshima in 1953 and asked Cousins to organize fund-raising for Hiroshima Maidens’ surgery in the United States.76 Tanimoto was also one of the six survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bomb whose experience of the bombing is portrayed in John Hersey’s 1949 bestseller Hiroshima, which had made Tanimoto’s presence known to prominent American intellectuals and allowed him to connect with them, including Cousins.

Cousins received broad support and funding for his Hiroshima Maiden Project from all over the United States, most notably from the readers of the Saturday Review, whom Christina Klein (2003) characterizes as American liberals who felt “tremendous guilt over the dropping of the atomic bombs” and “eagerly donated funds to the Maidens project as a way to expiate that guilt”.77

The State Department was initially sceptical of the project as the government was promoting its “Atoms for Peace” campaign and concerned that the publicity of hibakusha’s deformed bodies would fuel antinuclear movements worldwide. Cousins realized that the U.S government would intervene or even interdict the project if he framed the project as the acknowledgment of American responsibility, or expiation for its use of the bombs. Consequently, Klein argues that Cousins tactically “caste[d] the relationship between the United States and Japan in the intimate terms of one family member feeling ‘love’ and ‘duty’ to another”.78 In so doing, the Hiroshima Maidens project ensured the hierarchical relationship between the United States and Japan by portraying the United States as the benevolent, healthy, strong donor capable of providing humanitarian aid to poor fragile Asian women, and consequently generated patronizing sympathies from Americans.79

In the end, none of the Nagasaki Maidens were invited to the Hiroshima Maiden Project in the U.S. However, the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral, also known as the Cathedral of the Virgin Mary, became the recipient of U.S. reconstruction funds.

The Japanese media called the young female hibakusha “Atomic Maidens” (Genbaku Otome) whereas they were consistently called “Hiroshima Maidens” in the United States. In Japan, the Hiroshima Maiden project was portrayed as a form of U.S. atonement.80 The Chugoku Shinbun and Asahi Shinbun also reported that after returning to Hiroshima from the United States, both the physical and psychological traumas of the Atomic Maidens had been healed by advanced American reconstructive plastic procedures.81 The project was presented by the Japanese media as the symbolic restoration of postwar American-Japanese relations, which had been ‘wounded’ by the Lucky Dragon #5 Incident and the rise of Japanese antinuclear and anti-American sentiments.82 Likewise, the plastic surgery the Hiroshima Maidens received in the United States served not only as a metaphor for the ‘reconstruction’ of postwar Japan, showing the humanitarian spirit within the American consciousness, but also served to underscore the view that the trauma of the atomic bombing was curable through advanced U.S. medical technology.83

Both Yamaguchi and Tagawa were aware of the media discourse surrounding the Hiroshima Maidens in the United States and Japan. The American print media from 1955 to 1956 indicate that Yamaguchi and Tagawa had agreed that the remnants of the cathedral would serve as a reminder of the hostile history between the two countries, hence the demolition of the remnants and reconstruction of a new cathedral would be more appropriate than its preservation to mark the first sister city relationship between the United States and Japan. The statements of the two Nagasaki officials cited in the American newspaper articles also reveal Nagasaki leaders’ competitive stance toward Hiroshima. On May 6th, 1956, The New York Times reported Yamaguchi’s comment that “many Japanese people thought it ironic that the atomic bomb took the grandest proportionate toll of the Christian community in Nagasaki”. But, he continued that the Catholics regarded Nagasaki’s atomic bombing as divine “trial” and its victims as “martyrdom to end the war, the final appeasement of God for wrongs done”.84 Yamaguchi reportedly went on to assert that “we felt that the sacrifice of Japanese at Hiroshima must not have been enough in the sight of Lord”.85He then stated that he had received $40,000 for the reconstruction of the Urakami Cathedral during his trip to the United States. The article concluded with Yamaguchi’s call for further donations of $100,000 to help rebuild it.

Yamaguchi visited St. Paul soon after the St. Paul City Council signed the sister-city relationship on December 7, 1955. On December 11th, the St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press published an interview with Yamaguchi during which he described the goal of rebuilding the Urakami Cathedral. He stated that given St. Paul’s desire to enter into a sister-city relationship with Nagasaki, he would favour dismantling the ruins of the Cathedral and rebuilding it anew.

In the American news coverage of Tagawa’s statements, Nagasaki competition with Hiroshima was a central theme. On August 9, 1955, on the tenth anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, The Daily Courier of Connellsville Pennsylvania reported Tagawa’s comment that while Hiroshima had become known around the world, Nagasaki had been all but forgotten. On the same day, the United Press cited Tagawa’s claim that “Hiroshima uses the atomic bombing as political propaganda” and that Nagasaki would never do any such thing. He even asserted that Nagasaki Atomic Maidens would never ask the United States for reconstructive plastic surgery and removal of their keloids.86 On December 1, 1955, The Times Record in New York reported Tagawa’s emphasis on Nagasaki’s long history as Asia’s “window to the West” since the sixteenth century and its status as a “Christian city”.87 The article continued that “[t]hese long contacts with the West, Nagasaki Mayor Tagawa said, gave Nagasaki people a tolerant spirit, and they met the atomic bomb without rancor”.88 The article ended with the following statement: “Nagasaki folks are genial in character; and their feeling toward America and Americans is good on the whole”.89 While Tagawa clearly intended to appeal to the Americans by contrasting the characteristic of Nagasaki citizens with that of Hiroshima, he was apparently oblivious of the fact that the surgery of Hiroshima Maidens and the demolition and reconstruction of the Urakami Cathedral, both paid for with American funds and both directed toward overcoming rancor between atomic victims and Americans, were perfectly parallel.

In August 1956, interviewed by the St. Paul Dispatch, Tagawa, playing the Cold War card, noted that many Japanese people wanted to strengthen relations with the United States, but that Japanese communists were seeking such a relationship with the Soviet Union.90 The question of the renewal of the US-Japan Security Alliance (Ampo) was a politically and emotionally charged issue in Japan in the mid-1950s, a time when many Japanese feared it could lead to their involvement in another nuclear war.

The USIA in Japan was undoubtedly abreast of the debate over the fate of the ruins taking place in Nagasaki in the midst of the Japanese antinuclear peace movement. Typically, USIA staff were stationed in embassies and American Cultural Centres (ACC) in major cities, and were responsible for the administration of various cultural and international exchange programs, such as the Fulbright Fellowship. The American Cultural Center had an office in Nagasaki and its officers were aware that Nagasaki had been the top tourist destination in Japan in the postwar years. The ruins of Urakami Cathedral were the city’s most popular tourist attraction as the remnants were emblematic of the popular imagination of Nagasaki as an exotic Christian city and fulfilled visitors’ desire to witness the city’s recent history of the atomic bombing. At the same time, American policymakers may have been apprehensive about the potential that the ruins of the cathedral could serve as an icon of an international antinuclear movement.91

Dismantling the Ruins

After his return from the United States in September 1956, Tagawa became reluctant to comply with the committee’s recommendation for preservation of the ruins. By that time, a decade had already passed since the atomic bombing. Roads had been widened in the Urakami district; new houses had been built; and, the number of tourists had increased. With the reconstruction, other ruins left by the bombing had been dismantled. The ruins of the Urakami Cathedral were the only notable remaining vestige of the bombing in the city. Non-Catholic locals, especially hibakusha, were calling for their preservation as a material artefact to commemorate the tragedy. In contrast, very few Urakami Catholic hibakusha participated in the debate.

|

Remnants of Urakami Cathedral (front) and Peace Statue (back) in 1958 Photo courtesy of Takahara Itaru |

Within the Urakami Catholic community, some members urged Nakajima, the Urakami chief priest, to preserve the ruins. However, Nakajima characterized the ruins as ‘trash,’ which was already destroyed, so the preservation of the ruins was meaningless.92 Nakajima announced in February 1958 that dismantleming of the ruins would commence within the month. The following day, a local newspaper reported Mayor Tagawa’s comment that the dismantling was “unavoidable”.93 The committee members of the Atomic Bomb Material Preservation and Nagasaki councilmen were puzzled by the mayor’s position. They requested that the mayor hold a meeting to clearly communicate his intention.

At an emergency meeting of the Nagasaki City Council on February 17th, 1958, Iwaguchi Natsuo, a former reporter for the Nagasaki Nichi Nichi Shinbun and the youngest member of the council, argued for preservation of the ruins. Iwaguchi emphasized that the ruins were of historical value as material evidence of the bombing. He reminded the Council that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the only two cities in the world where boys and girls walked around with keloid scars, and that the full ramifications of the event remain unknown. Consequently, it was the duty of the citizens of Nagasaki to preserve what evidence remained to ensure that no such tragedy would ever occur again. Iwaguchi stated, “We want political leaders and visitors from all over the world to witness the horrific power of the atomic bomb and the baseness of war!”.94 Tagawa responded to Iwaguchi, saying:

It is undeniable that the ruins are valuable as a tourist attraction, but I do not believe they serve to promote peace. The horrific power of the atomic bomb has already been studied and documented scientifically, so even those who have never experienced its power can understand that such weapons should neither be used nor produced. Consequently, the existence of the ruins is superfluous. The question at hand is whether the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral are appropriate physical materials to convey the tragedy of the atomic bombing. Frankly speaking, my answer is no. The preservation of the ruins is not necessary to the pursuit of peace. Therefore, I will fully support for dismantling of the ruins and reconstruction of a new cathedral at the same site to respond to the wishes of the Catholic people.95

Tagawa argued that while atomic weapons were widely viewed as an absolute evil, that characterization was little more than ideological posturing. In practical terms, the possession of atomic weapons by the Soviet Union, the United States and Britain could be construed as a necessary condition for peace.

Tagawa’s comment on the idea of nuclear détente shocked the council members. Iwaguchi once again rose and questioned Tagawa:

Let me ask you then. Why are you going to erect a memorial statue for the twenty-six martyrs?96 Why are you going to replicate the Dutch House?97 Isn’t it because you want to convey the history of Nagasaki as Japan’s window to the West and how Western culture came to Japan? Isn’t it because you want to let the architecture silently speak to the viewers about such history in the present? We have been collecting tiles, bamboo, and other small objects exposed to the radiation of the atomic bomb as artefacts of the tragedy. Do you really believe that those little pieces will adequately convey the horror of the atomic bombing? We are asking you to preserve the ruins not as a symbol of hatred, but as a symbol of the baseness of war, as the spiritual cross of our sins! 98

Councilman Araki Tokugorō echoed Iwaguchi’s plea.

[The ruins] are invaluable because they will forever call out to humankind that never again should such ruins be produced. All the citizens of Nagasaki want to preserve the ruins! If they are removed, how will your successors, the mayors of Nagasaki in 100 or 200 years judge our decision? They must be preserved! Those ruins, please preserve them! Please preserve them! Mayor! Please!99

Despite the six decades that have passed, Iwaguchi’s speech and Araki’s plea, which are preserved in audio in Nagasaki’s archives, remain heart wrenching. They were not sufficient, however, to change Tagawa’s course of action.

The following day, the Council voted unanimously to preserve the ruins of Urakami Cathedral. Moreover, approximately 10,000 Nagasaki residents signed a petition calling for the preservation of the ruins. The Council Chair submitted a resolution for the preservation of the ruins to Bishop Yamaguchi. Nagasaki hibakusha groups jointly submitted three proposals with the Commission for the Preservation of Atomic Bomb Material to prevent the removal of the ruins. The first proposal was to remove the ruins of the front walls, but integrate the sidewalls into the new cathedral. In the event this proposal was rejected, the group proposed to transport the ruins to Peace Park. Their third proposal involved the excavation and preservation of the belfry, which remained buried after the explosion.100 On February 26, Tagawa met with Yamaguchi and asked him to consider the preservation of the ruins. On March 5, Tagawa reported that he had tried to negotiate with Urakami’s Catholic leaders; however, the remnants were deemed to be obstacles to the construction of a new cathedral. Consequently, the mayor asked the Council and the Committee to find a location to which the ruins could be transposrted, a practical impossibility given the scarcity of available land as a result of the 1955 construction of the giant statue ‘Peace Prayer’ in the Peace Park. Nonetheless, the Council and Committee continued to strive for the preservation of the ruins, including a proposal for the relocation of the proposed new cathedral, a plan rejected by Catholic leaders. They insisted that the cathedral be reconstructed on the same location, the site of the memory of the Urakami martyrdom.

In the final meeting in March, the city council voted to leave the ultimate decision to Mayor Tagawa. Iwaguchi and the hibakusha group then addressed three new proposals. The first proposal was to hold surveys all over Japan to discuss the fate of the ruins at the national level. The second proposal was to invite the National Commission for Protection of Cultural Properties (文化財保護委員会) to offer their opinion. The third proposal was to provide financial support not only for the preservation of the ruins, but also for reconstruction of a new cathedral.101 However, Tagawa dismissed their final plea.

On March 14th, 1958, the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral were dismantled. Very few people were present at the site during the demolition process. Only the statues of St. Mary in Mourning and St. John the Apostle, and a portion of the southern wall were preserved from the demolition after a last desperate plea from hibakusha groups.

On the day of the dismantling, Nagasaki Shinbun reported:

[The dismantling] began with the remnants of the front walls. Those remnants, however, made for extremely difficult work. The sturdy ropes meant to pull them down were cut. Nevertheless, by mid-afternoon, the wall collapsed. About thirty tons of ruins were pulled down by early evening.102

The article indicates that the ruins were fairly robust, despite the Urakami Catholic church’s claim that the remnants had posed a physical threat of collapse.103On March 29th, two weeks after the demolition of the ruins, Nagasaki City Hall caught fire and was largely destroyed. Along with the building itself, much of the municipal archives were destroyed, including the materials detailing Tagawa’s trip to the United States. The fire occurred on Saturday when few people were in the city hall. The cause of the fire remains unknown.104 As a result of the fire, it is difficult to assess exactly Tagawa’s position concerning the cathedral and the U.S.-Japan security alliance as it evolved during his trip, who he met and what they discussed.

|

|

| Dismantling of Remnants of the Cathedral Photo courtesy of Itaru Takahara | |

The construction of the new Urakami Cathedral was completed in October 1959. The question of how they eventually collected another $10,000 remains unknown. Three statues that survived the bombing were rehoused in front of the new cathedral, and a portion of the wall is located right beside the tower, making it the epicenter in the Nagasaki Peace Park. The Urakami Catholic leaders described the new cathedral as a symbol of the recovery and reconstruction of their community. However, Nagasaki perpetually lost its most powerful symbol of the dawn and suffering of the nuclear age.

Remembrance of Absent Ruins in Photographs

Today, the Hiroshima Atomic Dome is recognized internationally as a symbol of the advent of the nuclear age and of a universal desire for peace. However, few municipal officials in Hiroshima were interested in the preservation of ruins prior to the late 1960s. They felt that their preservation would be an obstacle to Hiroshima reinventing itself from the former imperial army city to a city of peace.106

The Hiroshima Atomic Dome was originally the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. Discussion over whether to preserve the remnants of the atomic bombing took place in Hiroshima, too. However, neither city officials nor the citizenry was interested in the conservation. In 1951, Mayor Hamai claimed that preservation of the remnants of the Hall would be wasting money since the collapse of the remnants was inevitable.107 Likewise, the president of Hiroshima University, Morito Tatsuo, stated that preserving the remnants would only be a discomfort and that the construction of a new building symbolizing peace would be far more valuable.108 The Hiroshima municipal government did not regard the remnants of the Hall as a potential tourist resource,109 whereas the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral became the most popular tourist attraction in Nagasaki, which was the more popular tourist destination for Japanese due to Nagai’s popularity and its image as the baptized city by the bomb in the 1950s, right up to the 1958 demolition.

In May 1960, a children’s group called “Hiroshima Paper Crane Society,” founded to honor Sasaki Sadako, who had died of lymph gland leukemia caused by the radiation poisoning of the atomic bomb at the age of 12, created a petition for the preservation of the remnants of the atomic bombing. Hiroshima Mayor Hamai, however, believed that “the ruins have no scholarly value as they could not reveal the power of the atomic bomb”.110 Meanwhile, the remnants of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall continued to decay and some civil engineers warned that they were on the verge of collapse. The mayor and city officials waited for the question to sort itself out.111

|

|

|

Remnants of the Cathedral and Urakami Priest Nakajima Banri (center) Photo courtesy of Itaru Takahara |

Statue of St. John the Apostle tied up with rope for transport. The footprint from a shoe is visible on the chest105 Photo courtesy of Itaru Takahara |

However, city officials began to recognize both the symbolic power and the potential of the ruins as a tourist attraction when civil groups and prominent figures, such as Gensuikyo and Yukawa Hideki, the first Japanese winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics, called for the preservation of the Dome, describing it as the “Memorial Cathedral of Hiroshima’s Atomic Bombing” and “Unparalleled World Cultural Heritage”.112 The mid-1960s reference to a “Memorial Cathedral” has a bitter irony after the grandest and truly historical Cathedral in the Far East had already been dismantled. In July 1966, the Hiroshima City Council unanimously called for the preservation of the Atomic Dome and set a target of 40 million yen to finance the project. They collected approximately 67 million yen from all over Japan and the work was completed in August 1967. In December 1996, the Atomic Dome was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 1970, Matsumoto Hiroshi, a professor of literature at Hiroshima University, wrote that the Atomic Dome is no longer a ruin of the atomic bombing since it obtained the status of an object of “perpetual preservation”.113 He claimed that the restoration of the Atomic Dome rather indicated the death of the ruins. His controversial statement poses a question of what the ruins signify to viewers. Ruins embody a sense of loss and irreversibility of the past. The fragmented body compels us to recognize that the remnants will eventually fall into decay and oblivion if we fail to reclaim them by generating action driven by critical thought by working through what the ruins mean to us in the present. Contending that the Atomic Dome no longer evokes such a sense of crisis or dynamism, Matsumoto concluded that the perpetual preservation of the Atomic Dome would not guarantee remembrance of the substance of the atomic bomb memory; rather the pretence to perpetually remember would accelerate oblivion by effectively precluding the sense of crisis in our remembrance, the essential condition for the possibility of inheriting the remnants left by absent others.

Many Nagasaki residents today lament the dismantling of the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral which deprived them of a powerful monument to the atomic bomb experience—one arguably even more powerful than Hiroshima’s Atomic Dome. However, the photographs of the ruins of the cathedral evoke in the viewer the sense of loss precisely because of our recognition of the perpetual loss. The ruins of the cathedral permanently remain on the verge of the second destruction, continuously appearing as something to be erased. The ghostly remnants in the photographs provoke the viewer’s sense of crisis that some important history and memory surrounding the ruins would be forever obliterated if s/he fails to reclaim what was lost. The ruins themselves never speak to us. To have the ghostly remnants become part of our present and our politics against multiple forms of injustice, it is necessary to articulate the significance of that event in the present. In other words, the ruins in the photographs prompt the viewer to construct and reconstruct the means for what is visible and seek what is not fully recovered from oblivion by searching the traces of the past.

The disentanglement of the political implications of the sister city relationship and the dismantlement of the ruins reveals how deeply Nagasaki was embedded within Eisenhower’s U.S. cultural diplomacy and the “People-to-People program” that aimed to integrate Japan into U.S. global policy. The detour to the 1950’s political landscape, in turn, illuminates the postwar history of Nagasaki. While it is known that Nagasaki housed Mitsubishi’s largest warship production site, and monopolized the manufacture of torpedoes during the Asia-Pacific War, it is largely ignored that Nagasaki remains one of Japan’s largest manufacturing sites for military production under the Mitsubishi Heavy Industrial Corporation.114 Though Mitsubishi’s production of warships was briefly interrupted during the American occupation, it resumed operations in 1950 with the outbreak of the Korean War.

In recent decades, Nagasaki’s economic development has relied heavily upon Mitsubishi’s prosperity through the production of weapons, nuclear vessels and nuclear reactors. The Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipping Company built the first Japanese-made Aegis warship, which was originally built by the U.S. Navy, for the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force in 1991.115 The Aegis Combat System also allows the sharing of military-strategic information between the United States and Japan.116 In addition, Urakami is still home to the only factory producing Japanese torpedoes.117 Put differently, Mitsubishi/Nagasaki is one of the major beneficiaries of American-Japanese collaborative efforts both to produce weapons and to introduce nuclear energy into the country, both in the service of the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance.

Nagasaki prefecture hosts the third largest American military base in Japan today. In 1946 the U.S. took over the Japanese naval base in Sasebo, just 68 kilometers from the epicenter. Sasebo was for 60 years Japan’s imperial military port city. During the Korean War, it was reorganized by the U.S. into a military port and housed one of the Headquarters of the United Nations Forces.118 After the end of the U.S. occupation, Japan Self-Defense Forces were established in 1954 and Sasebo also became the homeport for Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force. As well, the Nagasaki Airport has served the U.S military base in Sasebo as a point of entry into, and exit from, Japan.119 Nagasaki has been firmly integrated into the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance since the mid-1950s—the period when the debate over the ruins of the cathedral took place and the sister city relationship was made. As the U.S Navy states on its official website:

The important bilateral relationship between Japan and the United States that exists today is very much in evidence at U.S. Fleet Activities Sasebo, where ships of the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force and the United States Seventh Fleet share this excellent port.120