Translated with an introduction by Tze M. Loo

In early May 2015, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) reported that the 23 sites related to Japan’s industrialization in the Meiji period (“Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining”) met the criteria for designation as World Heritage sites. ICOMOS’ evaluation paved the way for the sites to be inscribed in the World Heritage list at the 39th session of the World Heritage Committee in Bonn, Germany. South Korea voiced its opposition immediately, citing the use of Korean forced labor at 7 of these sites, and criticized Japan’s nomination for attempting to obfuscate that history. Seoul demanded that Japan address the use of forced labor at these sites, but Tokyo rejected these calls as “political claims.” Japan and Korea met twice to discuss the issue (on 22 May and 9 June) but failed to reach any agreement. At the same time, Korea’s foreign minister met with his counterparts in Germany, Croatia, and Malaysia – all three are members of the 21-member World Heritage Committee – to present Seoul’s case against Japan’s World Heritage proposal. On 21 June, however, Japanese and Korean foreign ministers meeting in Tokyo announced their agreement to cooperate to ensure the inscription of both Japan’s Meiji industrial sites and South Korea’s Baekje Historic Area into the World Heritage list at Bonn.

The World Heritage Committee convened its meeting on 28 June, and was scheduled to vote on the Japanese sites on 4 July. At the last minute, the Committee announced a postponement of the vote by a day, citing the disagreement between Japan and Korea, and asked both countries to continue negotiations. The World Heritage Committee voted on 5 July, after Japan and Korea reached an agreement on the wording about Korean labor at the sites. During the voting process, Japan issued a statement regarding an “interpretive strategy” for the sites that would allow for “an understanding of the full history of each site”. It included the following:

More specifically, Japan is prepared to take measures that allow an understanding that there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites, and that, during World War II, the Government of Japan also implemented its policy of requisition.1

The Korean delegation took the floor following this. It noted that Korea “decided to join the [World Heritage] Committee’s consensus decision on this matter” because it had “full confidence in the authority of the Committee and trusts that the Government of Japan will implement in good faith the measures it has announced” before the Committee.2

The successful designation was initially welcomed by both Japan and Korea as a moment of cooperation between them on a difficult historical issue. This optimism about Japan-Korea reconciliation, however, quickly evaporated. Commentary the very next day in both countries on the meaning of Japan’s statement revealed a deep schism. Korea viewed the statement as Japan’s public acknowledgment of its use of Korean forced labor at the sites. However, Japan’s foreign minister declared that the statement’s use of the phrase “forced to work” did not mean “forced labor (kyōsei renko).” Further, Japanese newspapers decried the politicization of the nomination process, and complained that this “threw cold water” on attempts to improve Japan-Korea relations. Some news outlets have also began to point fingers by attributing the delayed vote at Bonn to Korea’s refusal to compromise despite their agreement to do so on 21 June. This issue has the potential to return in the future: the Yomiuri newspaper reported that Korean government officials have raised the possibility that a similar kind of diplomatic row will erupt again if Japan proceeds with its nomination of “The Sado complex of heritage mines” to the World Heritage List because of forced labor that was used there.3

Takazane Yasunori’s essay was published on 29 May 2015, more than a month before the World Heritage meeting. While Japan’s nomination was successful, Takazane’s essay remains a timely interrogation of Japan’s historical consciousness about the history of Korean forced labor at these sites, a problem that the mainstream Japanese press seems reluctant to tackle directly. The essay is also noteworthy for his questioning of UNESCO’s responsibility in this matter. TML

* * * * *

The Japanese government’s nomination of Gunkanjima, [or Battleship Island] formally known as Hashima, in Nagasaki Prefecture as a World Heritage site is likely to be adopted. But is it acceptable to ignore the historical fact that Korean and Chinese people were forced into labor under extremely poor conditions at the coal mine there?

UNESCO’s advisory body, ICOMOS, recently recommended to UNESCO that the 23 installations nominated by the Japanese government for the World Heritage as “Modern Industrial Heritage Sites in Kyūshū and Yamaguchi” are as a whole “appropriate for inscription.”

In Nagasaki, this recommendation was greeted enthusiastically, especially by the local media and tourism industry, but I was, to be honest, disappointed by it and by the “festive mood” in response. Was this a wise decision by ICOMOS? The nomination documents submitted by the Japanese government were inadequate in terms of acknowledging the whole history of each of the locations. Surely there were other ways for ICOMOS to proceed, such as by asking for the submission of additional materials?

In particular, one of the 23 suggested sites, Gunkanjima (Hashima Island) in Nagasaki Prefecture, an active coal mine until 1974, was worked by Korean and Chinese forced laborers during the 1930s and 1940s, and the terrible conditions they endured meant that many died. To be clear, I am not opposed to Gunkanjima’s registration as a World Heritage site under all circumstances. If Japan applies for registration predicated on this negative history (fu no rekishi) that acknowledges responsibility for this exploitation, then I think there is room for discussion.

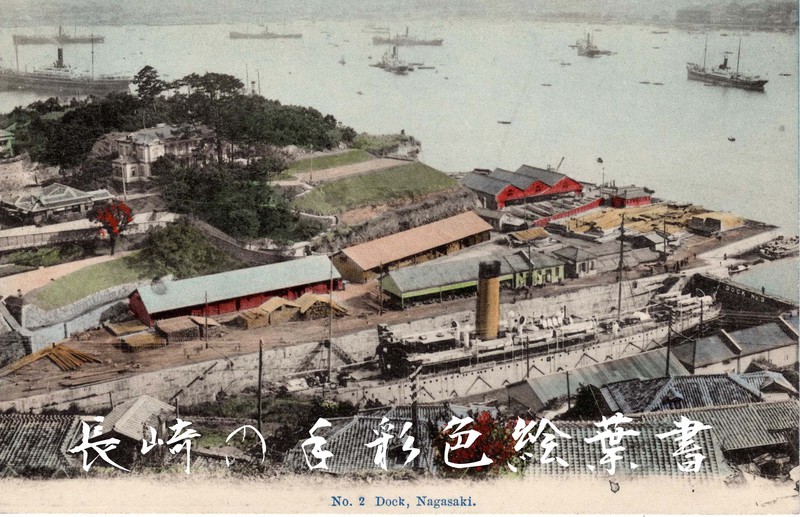

|

Hashima Island, also known as Gunkanjima (Battleship island) “Nagasaki Hashima 01” by Hisagi |

Sites like Auschwitz in Poland, Hiroshima’s atomic dome, and the English slave-trade port of Liverpool are registered World Heritage sites because of their negative histories, in order to provide materials for humanity’s self-examination, and warnings of actions that must never be repeated. However, the Japanese government does not regard Gunkanjima in that way.

Cries from those forced into labor

In January 2011, I learned of the existence of survivors who had worked as forced laborers on Gunkanjima from a DVD of a Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) program, and, visiting Korea, I met three such people who were in their 80s and 90s.

I heard their vivid accounts of personal experiences and their stories of suffering there. In speaking to them of the possible recognition of Gunkanjima as a World Heritage site, I was struck by their unanimous disbelief. “Isn’t this a concealment of history?” they asked. “What kind of experiences do people think we had there?” “Are Japanese people actually proud of this island’s history? Why?”

Because of this experience, I published If you listen carefully to Gunkanjima: Records of Korean and Chinese forced into labor at Hashima (Gunkanjima ni mimi o sumaseba: Hashima ni kyōsei renkōsareta Chōsenjin Chūgokujin no kiroku) later in 2011. I did so under the auspices of the “Committee for the Protection of the Rights of Zainichi Koreans in Nagasaki” – an organization with which I am affiliated and which has long worked with Korean atomic bomb survivors.

The South Korean government has already expressed the opinion that Gunkanjima clashes with the mission of the World Heritage Convention, which aims to protect heritage that possesses “universal values.” We should pay attention. According to South Korean government data, approximately 60,000 Koreans were pressed into service at seven of the sites, including Kyūshū’s coal mines, the Yahata steel works, and Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki shipbuilding works, where about 1,000 people died.

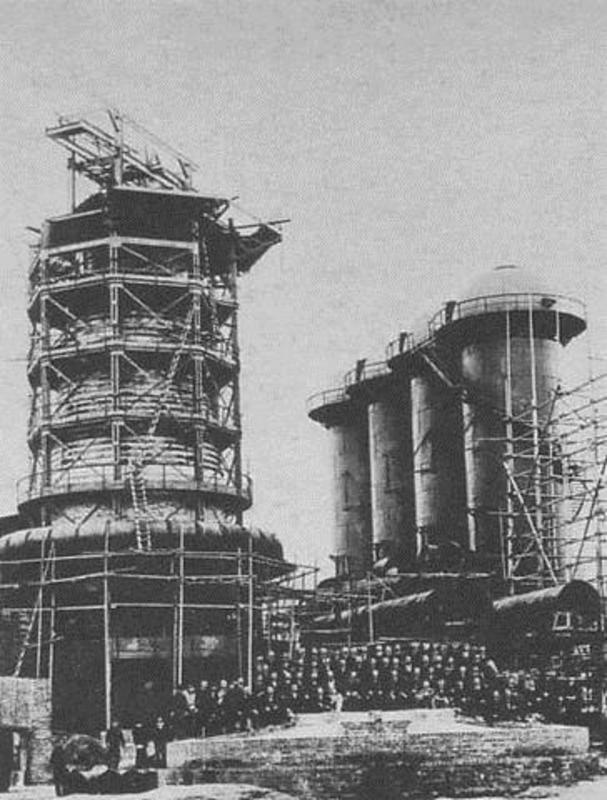

|

“Governmental Yawata Iron & Steel Works” in Mainichi shimbunsha, Ichi oku nin no Shōwa shi |

However, Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide responded that, “This is something that an expert organization has recognized. There is no need to introduce political claims as Korea has.”

But this is not a problem of politics, it is a problem of history. What does Japan mean by ignoring a historical event and rejecting it as a “political claim?” Is such an argument acceptable – or is it only acceptable in Japan? Such a claim is not persuasive to countries and peoples who have suffered the damage of invasion or war.

When foreign minister Kishida Fumio presented the Japanese government’s standpoint, he noted that “the years that are relevant to [the World Heritage designation] are the 1850s to 1910” and are “different from the time frame, historical assessment, and background context [of forced labor].”

But the very fact that Hashima began to resemble a battleship from afar – and thus acquired its famous nickname of Gunkanjima or Battleship Island – was due to the high-rise buildings on the island, even the oldest of which was built only in 1916. There are no pre-1910 buildings on the island today that could be added to the World Heritage Register. Does that not mean that the Foreign Minister’s remarks are divorced from reality?

Historical consciousness in question

It is also significant that while the 23 locations have been described as “industrial revolution heritage sites,” for some reason Shōkasonjuku in Yamaguchi prefecture’s Hagi City is included. It seems that the Japanese government wanted to include Shōkasonjuku at all costs, doubtless to cast Yoshida Shōin as the great philosopher and leader who led Japan into modernity.4

Yoshida Shōin, however, should be remembered not just as a precursor of the Meiji Revolution and the associated industrialization, but also for having drafted a grand philosophy of invasion. Yoshida Shōin inculcated these ideas into his disciples Itō Hirobumi and Yamagata Aritomo, the leaders of the Meiji era, and there is no question that they put them into action.5 From the First Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars, to the annexation of the Korean peninsula, and through the Manchurian Incident and the Second Sino-Japanese war, the modern Japanese state focused on territorial aggression.

Is not Korean and Chinese forced labor, of which Hashima was but one example, precisely one of the things brought about by Japanese imperialism? Shōkasonjuku too should not be added to the World Heritage register without any recognition of its negative history. The fact that Shōkasonjuku and Gunkanjima are without question joined by negative history should not be forgotten.

Furthermore, many of the Korean and Chinese people forced into labor on Gunkanjima were deployed to clean up the debris caused by the atomic bombing of Nagasaki in August 1945, and they suffered radiation exposure on entering the city. Others had earlier been forcibly moved from Gunkanjima to the Mitsubishi shipbuilding works in Nagasaki and suffered directly from the atomic bombing. Most of them passed away without ever receiving compensation for suffering A-bomb exposure. What would they think upon seeing this current push to celebrate Gunkanjima as a World Heritage site?

How should UNESCO decide this question now? There are rumors that UNESCO hopes that the Japanese and Korean governments, who have opposing viewpoints, will hold negotiations, which might also involve the Chinese government. But this is surely not the kind of problem that can be resolved by discussions between governments. A failure by Japan and Korea to reach an agreement will not lead to a settlement, but it is questionable for UNESCO to throw the problem back to national governments.. UNESCO must take full responsibility and make its own judgment, rather than simply accepting ICOMOS’s recommendation wholesale.

Japan should also recognize that the significance of this debate goes far beyond UNESCO’s approval or not of Gunkanjima as a World Heritage site. The more important issue is its own historical consciousness. How should Japan respond to Korean and Chinese criticisms on this issue? What kind of reply should Japan as the former aggressor give? As the 70th anniversary of the end of the war approaches, surely we have a duty to not be swept up in facile celebrations but instead to face history earnestly.

This article appeared in the May 29 edition of Shūkan Kinyōbi. Edited by Narusawa Muneo.

Takazane Yasunori is Professor Emeritus at Nagasaki University. He is Director of the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum.

Tze M. Loo is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Richmond and is the author of Heritage Politics: Shuri Castle and Okinawa’s Incorporation into Modern Japan, 1879-2000.

Recommended citation: Takazane Yasunori translated and introduced by Tze M. Loo,

Should “Gunkanjima” Be a World Heritage site? – The forgotten scars of Korean forced labor, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 28, No. 1, July 13, 2015.

Related articles:

• William Underwood, History in a Box: UNESCO and the Framing of Japan’s Meiji Era

• William Underwood and Mark Siemons, Island of Horror: Gunkanjima and Japan’s Quest for UNESCO World Heritage Status

• Richard Minear and Franziska Seraphim, Hanaoka Monogatari: The Massacre of Chinese Forced Laborers, Summer 1945

• William Underwood, Toward Reconciliation: The Nishimatsu Settlements for Chinese Forced Labor in World War Two

• William Underwood, Rejected by All Plaintiffs: Failure of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa “Settlement” with Chinese Forced Laborers in Wartime Japan

• William Underwood, Redress Crossroads in Japan: Decisive Phase in Campaigns to Compensate Korean and Chinese Wartime Forced Laborers

• Kim Hyo-sun, Allied and Korean Forced Labor at the Aso Mining Company and Japan-South Korea Relations

• William Underwood, Recent Developments in Korean-Japanese Historical Reconciliation

• William Underwood, Remembering and Redressing the Forced Mobilization of Korean Laborers by Imperial Japan

Notes

1 “Nihon seifu daihyōdan seimei bun,” Mainichi shimbun, 7 July 2015, 2.

2 Statement by the Korean delegation, Session of the World Heritage Committee, 5 July 2015 (accessed 8 July 2015).

3 “Kankoku ‘Sado kōzan’ mo chūshi,” Yomiuri shimbun, 6 July 2015, 2.

4 Translator’s note: Shōkasonjuku was the school established by Yoshida Shōin (1830-1859), who is well known for having tried to smuggle himself onto one of Perry’s ships. Several future political leaders who orchestrated the Meiji Restoration were educated at Shōkasonjuku. Popular interest in Yoshida Shōin—already substantial—is currently being hyped through NHK’s historical drama for 2015, “Hanamoyu,” whose main character is Shōin’s sister, Fumi.

5 In Yoshida Shōin’s words, “it is urgent that we now prepare militarily; we have enough ships and nearly enough cannon, so it is appropriate immediately to reclaim Ezo [Hokkaidō] and feudalize the various lords, then seize the moment and grab Kamchatka and Okhotsk, persuade Ryūkyū … pressure Korea … and then in the north divide Manchurian lands, and in the south acquire Taiwan and Luzon.” (The Collected Works of Yoshida Shōin, volume 1) Yoshida moreover advocated that the Shogun’s policy should be to “Cultivate national strength, carve up and subjugate the easy pickings of Korea, Manchuria and China, and make up for what we lose to Russia through trade with lands from Korea and Manchuria,” That is, after cultivating national strength, [Japan] should aim to enlarge its territory through military invasion. (The Collected Works of Yoshida Shōin, volume 5)