The original title of my proposed book about Hiroshima and Nagasaki was, “The Last Train to Nagasaki.” I believed the title conveyed how I would bridge the story of the two cities via the people who had survived both atomic bombings – the double hibakusha. In this manner, I thought I could correct the problem of how history all but forgot the second and even more powerful atomic bomb and its victims. As one survivor expressed the forgetting: “It is never good to be the second of anything.” I did not know how extreme the forgetfulness had become. In 2009, my editor discovered that almost no one at the publishing house knew what the name, Nagasaki, referred to – and thus the title change, to a name familiar to everyone: “The Last Train from Hiroshima.”

Approximately 300 people are known to have made the journey, aboard two trains, from Hiroshima all the way to Nagasaki in the wake of the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945. Of this group, approximately 90% were killed by the second atomic bomb. In “Last Train,” the double hibakusha bracket and interweave with the stories of other survivors, ranging from conscripted schoolchildren and doctors at Nagasaki to the origin of the thousands of paper cranes that were sent from the children of Hiroshima to the children of New York in 2001.

As a child of the “Duck and Cover” drills, I grew up to eventually embrace what I feared most (the very physics that made possible, the thermonuclear inverse to the Golden Rule). During the 1980s, I joined brainstorming sessions at Brookhaven National Laboratory, where we designed nuclear melt-through probes for exploration of new oceans turning up beneath the ice of Jupiter’s moon Europa – in addition to a Valkyrie rocket that could actually bridge the rest of the Solar System, and perhaps even interstellar space. Along the way, I met survivors of the atomic bombs, and began recording their stories. In 2001, I was working on forensic physics/archaeology in the ruins of the World Trade Center. In a landscape possibly even grayer than the surface of the moon, thousands of bundles of paper cranes were arriving, becoming the only splashes of color and beauty. I met the Ito and Sasaki families when they visited, and I learned from them the word Omoiyari – which may be rendered as empathy (translated, in America, as the “pay-it-forward” principle)–I learned it as a way of life, and not just a word.

In the New York death-scape, where expressions about “nuking” someone rolled too easily off people’s tongues, it occurred to me that almost no one really knew what the words “nuke-them” meant. Most seemed to regard the atomic bomb as an antiseptic weapon that instantly erased “the bad guys” and allowed those outside the target area to somehow just walk away. After I added new hibakusha interviews to my archive, and showed chapters to colleagues, the most important review I received (or probably ever will receive), came from archaeologist Amnon Rosenfeld – who had been very hawkish and believed in pre-emptive nuclear strike. After reading the draft, he said that everything he thought he knew about what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was wrong, adding that anyone who learns the truth, and who designs nuclear weapons or plans first use for any reason whatsoever, “has found the unforgivable sin.”

My hope is that others will come to the Rosenfeld conclusion. My hope is that this glimpse of the past (through the science of what happened, combined with the human perspective), will in at least some small way help to prevent the hibakusha experience from becoming prophecy for much of our world during the next thirty years. My hope is that nuclear war will have ended, forever, at the black granite pinnacle marking the hypocenter of Nagasaki.

After the first American edition of “The Last Train from Hiroshima” was published in 2010, I learned that one of the Tinian Island aviators I interviewed had exaggerated part of his war record, and I announced my mistake and the need for a correction from New York, on the John Batchelor Show. This seemed to have opened the floodgates for e-mailers denying the existence of “shadow people” and other thermal effects near the hypocenters, along with denial of radiation effects. The e-mail wrecking crew managed to spoof the NY Times and my publisher by pretending to be everyone from famed Hiroshima artist and hibakusha Keiji Nakazawa to veterans threatening mass public burnings of the book.

The real Keiji Nakazawa was in fact on my side and took special interest in my attempts to learn more about the atomic orphans. He helped me and Steve Leeper (then Director of the Hiroshima Peace Cultural Foundation) to fill in a blank space in our history (the orphans). With Nakazawa’s input, the atomic orphans can finally speak loud and clear- after seven decades. Real veterans of the 509th never made threats to my publisher about pickets and book-burnings, and in fact veterans and their families contributed details to the new edition. Nonetheless, the publisher had by then prevented book burnings (as threatened in emails from “veterans”), by withdrawing the first edition and pulping it. In the real world, you will be hard-pressed to find an American veteran who endorses censorship. No less an authority on such matters than Tom Dettweiler (who survived the destruction of the Pentagon’s Navy wing on 9/11 on account of having been called away for an eye exam), observed: “Despite past attempts to suppress this history, Charles has succeeded in a detailed immortalization of one of the true turning points in human existence… [It] should be required reading for all those making decisions of war.”

The ultimate accomplishment of 2010’s internet hoaxers and impersonators was to bring many new truths to light. Chief among these was the coming forth of survivors who had hidden their experiences, and who had intended to take their stories to the grave. For most, speaking of it was very difficult, often a very painful experience. I cannot thank them more, for their bravery.

Among these, in the new edition (To Hell and Back: The Last Train from Hiroshima, Rowman and Littlefield https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781442250581/To-Hell-and-Back-The-Last-Train-from-Hiroshima, August 6, 2015), are four new and more complete accounts from the double hibakusha.

I first heard about the double atomic bomb survivors from the father of a friend, who was trying to learn what happened to Kenshi Hirata and who (despite his background in the Federal Bureau of Investigation), died before finding any clues as to where the Hirata family had gone into hiding after 1957. Kenshi Hirata is one of the people who came forth after the 2010 controversy, and what has emerged is one of the most touching and improbable love stories in all of human experience.

We now have, finally, the rest of Kenshi Hirata’s story. I have excerpted and adapted the Hirata history below from the several chapters through which this family’s story arc weaves – including information about what was happening around him, to provide the context of time and place.

|

[Kenshi Hirata [Illustration: CP] |

AT A QUARTER-PAST eight on August 6, 1945, near the center of a pomegranate’s volume of compressing uranium, the vast majority of the bomb’s energy had radiated from a spark scarcely wider than the tip of young Setsuko Hirata’s index finger. By the time the golden white plasma sphere had spread eighty meters wide—still within only one small part of a lightning bolt’s life span—the spark had generated a short-lived but very intense magnetic field, from which streamers of iron and tungsten nuclei were shot-gunned toward the ground and toward the stars, at up to 90 percent light speed.

Setsuko Hirata was seated in her living room, slightly to the south and almost directly beneath the magnetic shotgun. Accelerated fragments of atomic nuclei came down through tiles and roof beams and either stopped inside her body or kept going until stopped by the first hundred meters of sand and bedrock. Neutrinos also descended through the roof. Born of the so-called weak force, their interactions with the world were so weak as to be utterly ghostly. Almost every one of them that encountered Setsuko continued through the floor without noticing her, then traveled with the same quantum indifference through the Earth itself. The very same neutrinos that passed through Setsuko, drawing a straight line between her and the bomb, and through nearly 5,000 miles of rock, emerged through the floor of the southern Indian Ocean and sprayed up toward interstellar space. Setsuko’s neutrino stream would still be traveling beyond the stars of Centaurus, beyond the far rim of the galaxy itself – still telling her story (as it were), long after the tallest skyscrapers and the Pyramids had turned to lime.

When Setsuko’s neutrino spray erupted unseen, near the French islands of Amsterdam and St. Paul, not quite 22 milliseconds after detonation, she was still alive.1 Ceramic roof tiles, three meters above her head, were just then beginning to catch the infra-red maximum from the flash—which peaked 150 milliseconds after the first atoms of uranium-235 began to come apart. The tiles threw a small fraction of the rays back into the sky, but in the end, they provided Setsuko with barely more protection than the silk nightgown her beloved Kenshi had bought her only a few days earlier during their honeymoon at the Gardens of Miyajima.

Overhead, along the lower hemisphere of the blue-to-gold to blue-again globe that expanded from the place where the bomb had been, the instantaneous transformation of matter into energy had produced a light so intense that if Setsuko were looking straight up, she would have seen the hemisphere shining through the single layer of roof tiles and wooden planks as if it were an electric torch shining through the bones of her fingers in a darkened room. And within those first two-tenths of a second, she might have had time enough to become aware of an electronic buzzing in her ears, and a tingling sensation throughout her bones, and a feeling that she was being lifted out of her chair, or pressed into it more firmly, or both at the same instant—and the growing sphere in the sky… she might even have had time enough to perceive, if not actually watch, its expanding dimensions.

Setsuko’s husband, Kenshi, had been working as an accountant at the Mitsubishi Weapons Plant, slightly more than four kilometers away, when through a window came the most beautiful golden lightning flash he had ever seen, or imagined he would ever see. Simultaneously there was a strange buzzing in his ears, a sizzling sound, and a woman’s voice crying out in his brain. He would suppose years later that maybe it was his grandmother’s spirit—or more likely Setsuko’s. The voice cried, “Get under cover!”

With all the speed of instinctive reflex, he dropped the papers he was carrying, dove to the floor, and buried his face in his arms. But three long seconds later when the expected shockwave had not arrived, he was left in adrenalized overdrive—with time to pray.

Outside his Mitsubishi office, in utter silence, a giant red flower billowed over the city, rising on a stem of yellow-white dust.

Kenshi’s prayers seemed to have been answered—yet again. He had walked away from the fire-bombing of Kobe on March 16-17, 1945 without a single blister or bruise, initially thinking himself a bit unlucky because he should never have been there in the first place; and Kenshi would never have been there, had he not finished his work in Osaka a day early and departed for Kobe ahead of schedule. Two nights after surviving Kobe, he learned that Osaka, too, had been heavily bombed. Indeed the very same hotel in which he should have been sleeping took a direct hit, with no survivors. At Hiroshima, Kenshi owed his survival to an instinct to obey an inner voice, and to the fact that the bomb had disappointed its creators, performing at only about half its intended yield (up to 12.5 kilotons), and sending forth a blast wave that was all but fractionally spent by the time it reached him. Kenshi’s next instinct did not serve him so well as his obedience to the voice. When he dropped to the floor, his initial impression was that a number of huge incendiary bombs were exploding right on top of the building and that he would be cremated even before he could finish the first lines of a prayer. But nearly five full seconds followed the flash, and the light itself began to fade without a hint of concussion—The bombs have not struck the building—

The multiple bombing-raid escapee raised his head to see what was happening around him. A young woman nearby had crept to a window and peeked outside. Whatever she saw in the direction of the city, Kenshi would never know. She stood up, uttered something guttural and incomprehensible, and then the blast wave—lagging far behind the bomb’s light waves—caught up with her. By the time the windowpanes traveled a half-meter, they had separated completely from their protective cross-hatched net of air-raid tape, emerging as thousands of tiny shards. Like the individual pellets of a shotgun blast, each shard had been accelerated to more than half the speed of sound. The girl at the window took at least a quarter-kilogram of glass in her face and her chest before the wind jetted her toward the far wall.

Kenshi did not see where she eventually landed. Simultaneous with the window blast, the very floor of the building had come off its foundation and bucked him more than a half-meter into the air. He landed on his back, and when he stood up he discovered to his relief that he was completely unharmed, then discovered, to his horror, that he was the only one so spared. All of his fellow workers—all of them—looked as if they had crawled out of a blood pool.

We must have taken a direct hit after all, Kenshi guessed. He did not realize the full magnitude of the attack until he stepped outside. In the distance, toward home, the head of the flower was no longer silent. It had been rumbling up there in the heavens for more than a minute, at least seven or ten kilometers high now, and it had dulled from brilliant red to dirty brown, almost to black. As he watched, the flower broke free from its stem and a smaller black bud bloomed in its place. It was, a fellow survivor would recall, like a decapitated dragon growing a new head.

A whisper escaped Kenshi’s lips: “Setsuko…”2

#

KENSHI MADE HIS WAY toward the center of the city. He had no choice. His wife was in there, somewhere beneath the dragon’s head. Within perhaps a thousand meters of the place he believed to be home, the streets and fields sprouted what seemed to be thousands of tiny flickering lamps. He could not determine what the lamps might actually be. Neither could any of the scientists who would hear of this later. Each jet of flame was about the size and shape of a doughnut. Kenshi knew that he could easily have extinguished any “ground candles” in his path merely by stepping on them; but he was “spooked” by an instinctive sense that it might somehow be dangerous to touch the fiery doughnuts, so he stepped around them instead.3 He thought of Setsuko. He passed men and women whose backs had been seared by the flash, but it was not the flash-burns that caught his attention and stuck in his memory. The people appeared to be growing strange vegetation out of their roasted flesh. It occurred to Kenshi only much later that thousands of glass slivers must have been pulled from the windows of every building and driven through the air like spear points. He thought of Setsuko. Limping, the young accountant circumnavigated a giant column of flame in which steel beams could be seen melting. He thought of Setsuko. Nearer the hypocenter, not very far from the city’s Municipal Office, he passed over a warm road surface upon which a great fire must have risen, then inexplicably died. All of the people simply disappeared here, and all of the wooden houses, on either side of the road, were reduced to grayish-white ash. He thought of Setsuko. The main street leading toward home and Hiroshima’s famous “T”-shaped bridge seemed more like a field than a road. In the middle of the field, he found two blackened streetcars. Their ceilings and windows had vanished and they were filled with lumps of charcoal that turned out to be passengers carbonized in their seats. The trolleys had apparently stopped on either side of the street to pick up more passengers, and two people were about to ascend the steps of one vehicle when the heat descended, and caught them, converting them into bales of coal with shirt buttons and teeth. In every direction, Kenshi saw pieces of people, and horses, and oxen, looking like charcoal. He thought of Setsuko, now blaming himself for their ill-omened honeymoon excursion, nearly two weeks earlier, to the Shrine Island of Miyajima.

There was a strange taboo in connection with the Miyajima Shrine. It had been dedicated to a goddess who was believed by the older generations to become jealous if a newly married husband and wife climbed the sacred steps together. If the taboo was violated, the old people said, the wife would shortly die. But Kenshi’s friend, a local innkeeper who had arranged honeymoon lodgings for them near the island’s gardens, had scoffed at this and said it was pure superstition. Since they had come all the way to Miyajima together, he advised, surely they should go at once to the famous shrine. So they did. And now, during the journey from his office into the heart of Ground Zero, Kenshi repented of it many times.4

#

THE STREETS OF HIROSHIMA were full of intriguing, seemingly impossible juxtapositions between the utterly destroyed and the miraculously unharmed. The roof tiles of Kenshi’s home had boiled on one side and were cracked into thousands of tiny chips, and evidently the entire structure was simultaneously roasted and pounded nearly a half-meter into the earth. A few doors away, evidence of a gigantic shock bubble, in which the very atmosphere had recoiled at supersonic speed from the center of the explosion, could be seen in the evidence of the bubble’s immediate aftereffect—the “vacuum effect” that had developed behind an outracing shock wave, pulling everything back again towards the center, toward the actual formation point of the mushroom cloud, almost directly overhead. The force of the imploding shock bubble had also pulled air-filled storm sewers up through the pavement. These manifestations only hinted at the forces unleashed when the low-density bubble, its walls shining with the power of plasma and super-compressed air, had spread and cooled to a point at which the press inward by the surrounding atmosphere started to become stronger than the heat and shock pushing away from the uranium storm. At this point, the shock bubble was only about 250 milliseconds old—just a quarter-second past Moment Zero and 400 meters in radius. When the bubble collapsed, less than two-tenths of a second later and nearly twenty blocks wide, the updraft experienced directly below, in Kenshi’s neighborhood, was amplified by the almost simultaneous rise of the retreating plasma, which behaved somewhat like a superheated hot-air balloon. As it rose and lost power, it had cooled from a fireball to an ominous black flower head, and had begun to shed debris the way a flower sheds pollen. Bicycles, bits of sidewalk, planks of wood, even half of a grand piano, fell out of the cloud, more than 800 meters away from the hypocenter.5

And yet, amid all this havoc, pieces of bone china and jars of jellied fruit lay unbroken upon the ground. Kenshi discovered that trees, although dry roasted and stripped of their leaves, were still standing upright and unbroken in a 30-meter wide area just outside of his immediate neighborhood. Along other points of the compass, everything either fell apart, or disappeared. Normally, one should not have been able to see the mountains or the weather station’s transmission tower from this location because there were rows of buildings in the way. But whenever the gusts of smoke and dust pulled apart, it was easy to see that the obstructions were all gone, now. The city was… flat. The whole thing. Little seemed recognizable, except broken sewing machines, concrete cisterns, blackened bicycles and streetcars, and piles of reddish-black flesh everywhere, a few vaguely in the shapes of human figures, or occasionally in the shapes of horses.

The Mitsubishi accountant would probably have escaped Hiroshima with no radiation injury at all had he not gone into the center of the blast area searching for Setsuko. Once he breathed the dry dust, then cleared the dust from his throat by drinking brownish-black water from a broken pipe, his cells were absorbing strange new variations on some very common elements. These new incarnations, or isotopes, tended to be so unstable that by the time he awoke in the morning most of them would no longer exist. Like little energized batteries, they were giving up their power. Unfortunately, they were discharging that power directly into Kenshi’s skin and stomach, into his lungs and blood. The quirk that spared him a lethal dose was the initial collapse of the shock bubble and the rise of the hot cloud. A substantial volume of pulverized and irradiated debris had been hoisted up into the cloud, and most of the poisons had already fallen kilometers away as black rain. Even in terms of radiation effects, in its own, paradoxical way, the central region of Ground Zero was sometimes the safest place to be. It was all relative, naturally: Mr. Hirata’s neighborhood was still hot with radioactivity; but places farther away were even hotter.6

By nightfall of that first day, Kenshi had positively identified a particular depression in the ground as his home. Only a day before, the house and garden were surrounded by a beautiful tiled wall—and now, chips of those distinctive tiles were strewn through the embers. The large iron stove that had heated bathwater for Kenshi and his bride seemed to have been hammered into the ground, but it still appeared to be located in the right part of the house. Only a few steps away, he unearthed kitchen utensils, which though deformed by heat and blast looked all too painfully familiar. They were gifts from Setsuko’s parents.

Kenshi had an odd instinctive feeling that the ground itself might be dangerous, and that he should leave the city immediately. The thought that stopped him was Setsuko: If she is dead, her spirit may feel lonely under the ashes, in the dark, all by herself. So I will sleep with her overnight, in our home.

Around midnight, he was awakened by enemy planes sweeping low, surveying the damage. The sky, in a wide, horizon-spanning arc from north to east, glowed crimson—reflecting the fires on the ground. Though there was little left to burn in what American fliers were already calling Ground Zero, flames grew all around the fringes of the bomb zone, creeping outward and outward.

The planes circled and left. Kenshi put his head down again, upon the ashes of his home, and lay in the otherworldly desolation of the city center. The silence of Hiroshima was broken intermittently by more planes and by explosions near the horizon in the direction of the waterfront and the Syn-fuel gas works. As the ring of fire expanded to the gas tanks, there were no working fire hydrants or fleets of fire trucks, and only a handful of firefighters were left alive to prevent the tanks from igniting. Kenshi heard huge metal hulls rocketing into the air on jets of flame, crashing back to earth one by one, and shooting up again. But Ground Zero itself was deceptively peaceful, and the noises that reached Kenshi from the outside did not trouble him. He was too exhausted and too filled with worry about Setsuko’s fate. If anything, the distant crackle of flames—even the occasional pops and bangs—lulled him into a deep slumber.7

#

THE FIRST SOLDIERS to reach the hypocenter came only an hour ahead of sunrise. The War Ministry had sent them in with stretchers—for what purpose, they could not understand. “There was not a living thing in sight,” one of them would later recall. “It was as if the people who lived in this uncanny city had been reduced to ashes with their houses.”

And yet there was a statue, standing undamaged in a place where not a single brick lay upon another brick. The statue was in fact a naked man standing with arms and legs spread apart—standing there, where everything else had been thrown down. The man had become charcoal—a pillar of charcoal so light and brittle that whole sections of him crumbled at the slightest touch. He must have climbed out of a shelter about a minute after the blast, chased perhaps by choking hot fumes from an underground broiler into the heart of hell. The fires killed him and carbonized him where he stood.8

The soldiers found an even more disturbing statue, covered in gray ashes. It appeared to have spent the last moment of its life trying to curl up into a fetal position. One of them probed it with a rod, expecting it to crumble apart. Instead, it opened its eyes.

The soldier flinched and asked, “How do you feel?” There seemed to be nothing else to say.

Instead of saying what he felt like saying—How do you think I feel, you moron?—the man replied that he was uninjured and explained, “When I came home from my job, I found that everything was gone, as you see here now.” The man insisted he needed no aid in leaving, nor did he wish to leave.

“This is the site of my house,” he said. “My name is Kenshi.”9

Without any further words or fuss, they left, and he began to dig. Even when Kenshi realized that the cloud had risen directly over his home, he prayed and held out hope that Setsuko might have somehow escaped harm. When he set out from the dockyard, he had packed a few extra biscuits for her. Now, a day later, he dug on all fours into the compressed ashes of his kitchen, descending nearly a half-meter—almost knee-deep. Whenever he paused to eat a biscuit or to sip water from a broken pipe, he sprinkled a share of the food and water ceremonially onto the ground—an offering to his bride of ten days.

As the August sun climbed higher and a snowfall of gray ashes blew through, the pipe stopped dripping. Kenshi was soon out of water as well as running low on biscuits, but he continued digging, hoping against knowledge that his failure to find any bones meant that Setsuko might not have been home when the flash came. For a while, believing he might have dug deeply enough to have found Setsuko if she had died at home, Kenshi left to search the nearest riverbank, wishing he might find her miraculously among the living. But hope died the moment he understood the condition of the few who were still moving among the bodies. Kenshi would never be able to forget their desperate faces, calling for “Water… water… water,” while he cried out for Setsuko. Finally taking some small measure of relief from the realization that Setsuko was not among this suffering multitude, Kenshi Hirata walked back toward the center of Ground Zero, and continued his excavation of the kitchen.

As exhaustion, thirst—and now hunger—began to compete with the first mild signs of radiation sickness, three women from his neighborhood returned to the ruins. Like Kenshi, they had been away, sheltered from what they had come to call the pika-don (the “flash-bang”). The oldest of them, the head of their neighborhood association, had rediscovered the place where emergency rations were buried and had directed the excavation of three large sealed cans of dry rice. Seeing Kenshi, and hearing his pleas for anyone who might have encountered Setsuko, she went straight off to a nearby pit in the ground that was filled with glowing red coals of wood. She mixed some of her own water ration with rice and cooked a bowl of mildly radioactive gruel for Kenshi. He would recall later that he was moved to tears by the kindness of this woman. He never saw her again.

After he ate the bowl of rice soup, he felt reenergized despite slight waves of nausea and resumed his search for Setsuko.

He excavated the entire kitchen, knowing that his wife loved cooking more than almost anything in the world, and that she fancied herself a top chef who could turn even the most meager rations into the most subtle flavors by coaxing spices and herbs from what most people called termites and weeds and citrus ants. The kitchen, he decided, was where he would most likely have found her at 8:15 a.m.—planning how to bulk up a cup of stale soybeans and turn it into what she had promised to be “a taste like walking on a cloud.”

When the dust of the kitchen had produced not the slightest trace of her, Kenshi began to grasp again, ever so slightly, at hope. He was soon joined by ten men who worked in the city’s sawmill. They knew the couple well and had heard of Kenshi’s distress.

They moved from the kitchen to the living room, excavating almost knee deep, and not a single trace of bone was found.

“She is not here,” Kenshi said. “She is still alive somewhere.”

“In order to make sure, we must dig a little deeper,” one of his friends said.

Minutes later, hope died again. His friend unearthed what seemed to Kenshi to be only a bit of a seashell.

“We both love conches and giant clam shells,” Kenshi insisted. “Setsuko uses them as table decorations!”

But already he knew in his heart that it was a fragment of human skull. The men quietly stepped back. Suppressing an uneasy feeling, Kenshi excavated gently with his fingertips, slowly widening and then deepening the area from which the “shell” had come. He touched little white scraps of spine, and found in them a pattern that indicated to him her final moment. She had been sitting when… it happened.

From the kitchen he excavated a metal bowl, singed but otherwise completely undamaged. Kenshi recognized it as the very same bowl he and Setsuko had brought with them from her parents’ home on the train to Hiroshima, only ten days before.

Ten days, he lamented, and this poor girl’s bones are to be put in this basin that she had brought with her from her native place.

He was thirsty under the broiling sun of midsummer. Sweat had formed long streamers down his back and his trousers were soaked. He felt faint. His friend from the sawmill offered him water and he drank, then sprinkled some of the water over the basin—in the sense of giving his wife the last water to the end of her short life.

“The lumber mill is gone and there is no guessing what will become of us now,” his friend said, then announced that he and his wife had been hoarding a small ration of fine white rice and dried fish, just in case the gradually worsening conditions came down to what westerners called “a rainy day.”

“Well, it’s been raining fire and black ice and horse guts,” the mill owner said. “So, this must be the day.”

He invited Kenshi home for a late but hearty lunch, and offered a place to stay until he decided where to go next.

Kenshi had already decided. As a surviving member of Mitsubishi management, he would be able to get priority seating on any trains still running. “If I can get to Koi or even all the way out to Kaidaichi Station,” he said, cradling the bowl of bones close to his chest, “then I will be able to find a way to bring Setsuko home to her parents.”

“Then all the more reason for you to have a good meal before you leave,” his friend insisted.

On the outskirts of the city, the mill owner’s house had survived behind a hill with only a few roof tiles dislodged. Nausea came and went, which made it easier for Kenshi to eat slowly and to keep his portions small. He did not want to take too much of the last good meal in town for himself, and away from his friends. All the while, the bowl from his own kitchen lay at his side. From the bones of his wife, isotopes of potassium and iodine were being liberated. They settled on Kenshi’s trousers, and on his skin, and in his lungs.

While they ate, a young soldier came to the door with news that Hiroshima Station might never run again, and all of the high-priority seats at Koi Station were already taken for the afternoon of August 7. No trains were running out of Kaitaichi, owing to what the sixteen-year-old message-runner called “the most amazing train wreck ever!”

He explained excitedly how a train leaving Hiroshima during the flash had been fried so severely that even its deadman switches must have failed: “The thing shot right through Kaitaichi and just kept on flying. They say it was doing at least a hundred-and-fifty K when it finally hit a truck in a crossing and went off the rails!”

Kenshi merely thanked the boy for his report and asked him if any trains would be leaving Koi tomorrow.

“Yes,” he said. “There’s one leaving at 3 p.m., and you have provisional seating—which means you’re on it, as long as you can get there.”

Kenshi decided to make an early start. Many roads and bridges had ceased to exist, and how long the walk to Koi would take was anybody’s guess. He filled his canteen and put two biscuits and a few grains of rice into his pants pocket, then cut some strings and wrapped a cloth tightly over the top of the basin so that Setsuko’s bones would not spill if he tripped on the debris that filled the streets.

Before he left, Kenshi asked his friend for permission to pick a flower from his garden. Then, saying his thank-yous and good-byes, he went down to the river, where he threw offerings of a flower and rice grains into the water and bowed three times, in accordance with a Buddhist tradition that acknowledges a place of the dead.

Bodies were now being pulled from both sides of the river, and on the road ahead, mass cremations had already begun.

How, Kenshi wondered, was he going to tell Setsuko’s parents what happened to her? He could think of nothing else. He did not know yet that he would soon have much else to think about. It might even be said that his rendezvous with history these past two days had been merely the twilight before the dawn.

Kenshi Hirata reached Koi Station with time to spare; and at three o’clock on the afternoon of August 8, he set out to bring Setsuko’s bones home to her parents, aboard the last Nagasaki-bound train to depart Hiroshima.10

A Hiroshima survivor named Kuniyoshi Sato would later record that, aboard the night train, he sat across from a pale figure who was sweating profusely. Kuniyoshi would relate, decades later, that the anonymous fellow traveler was holding a cloth-covered bowl on his lap, and this he jealously guarded, as if it were filled with gold.

“What are you holding, there?” Kuniyoshi asked.

“I married just last month,” the stranger replied. “But my wife died. I want to take her home to her parents.” And then, after a pause, the man lifted the cover from his bowl.

“See? Do you want to look inside?” He spoke these words in a tone that also said, See? This is what you get for sticking your nose into other people’s lives.

The bowl was filled with scraps of human bone. And, though the train was very crowded and it seemed very unlikely that Kuniyoshi would be able to find another seat, he stood and hurried away.

Far behind Kuniyoshi, beyond the man with the bowl, the atomic bomb had left a child forever perplexed about why, following the cremation of his father’s body, he found “numerous shards of glass among his bones.” It left a soldier who walked nearer the hypocenter than the foundations of Kenshi Hirata’s house, unable to quite explain the positions into which people inside a bank had been frozen. It became possible to imagine that a demon from Dante’s hell had waltzed through the building, touching everyone with instant death, and posing them.

Being among the first soldiers into the hypocenter, Junichi Kaneshige was already absorbing dangerous levels of radiation by the time he entered what he believed had once been the Geibi Bank. Afterward, he would write about finding people thoroughly carbonized on the upper floors and near the windows. They fell apart at the slightest touch. Moving deeper into the ruin, he discovered a particularly horrible shock-cocoon – a space in the building that had been left disconcertingly intact, preserving a moment that was more or less fossilized in the midst of symphonic devastation: “Descending the staircase to the basement,” he recorded, “we found a certain female. She sat squarely upright, clad in a yukata dress amidst [what must have been] plenty of shower water coming down from the water tap installed above. Her face was pale, with her long hair hung over her shoulder down to her breasts. Although the surroundings had been burned down, the woman died in a dignified posture under the shower water. This scene was rather more emotion-stirring and provocative than the charred human bodies.”

Junichi would eventually recover from the ravages of radiation poisoning, but never from the image of the woman within the incinerated bank.11

#

KENSHI HIRATA ALMOST DOZED off, but a sudden bump in the train tracks and a bright flash outside his window snapped him to full alertness. Off to one side, an orange glow began blooming against the sky, spreading there, brightening. The city of Yahata was dying under what he guessed to be at least a fifty-strong B-29 raid.

He thought of Setsuko.

Kenshi’s intestines still did not feel quite right, and he noticed bleeding under the skin of his fingers – and though he felt weak and achy, he was afraid that if he started to doze off again, he would drop the bowl of precious bones lying on his lap.

Two additional swarms of night-raiders helped him to keep sleep at bay. En route to Nagasaki, he witnessed the fire-bombings of two more towns: Tobata and Yawata. It was difficult for him to believe the situation had deteriorated to such an extent that B-29s were being sent far afield of the cities, to target even the small towns.12

About mid-morning, Kenshi reached his parents’ home, on what was to become the shadow side of a tall hill. By then than an hour separated him from his second Moment Zero, barely more than 3.3 kilometers from the next hypocenter.

As he approached the steps, Kenshi’s parents came running through the door with tears in their eyes. At that same moment, an air-raid siren began to signal what was likely just another in a seemingly endless series of false alarms. False or not, he was not taking any chances. Mindful that a second flash might appear, he told his parents to come inside with him quickly and to stay away from the windows.

Kenshi’s father was shocked at the sight of him—pale, with shaking hands, and with perspiration running down his cheeks, his chest, and his legs. He looked like a man half starved to death.

“Have you eaten?” his mother asked.

“Not hungry,” he said. “I can’t seem to keep anything down.” He cradled the wedding bowl to his chest and rocked it gently, and his father bowed his head.

“I knew you were alive,” Mrs. Hirata said. “Even when no more word was coming out of Hiroshima, I knew you were still in this world.”

“And Setsuko?” his father asked, almost at a whisper.

Kenshi lifted the bowl and bent his head toward its rim, and kissed it. “This is all that’s left of her,” he replied.

“We already knew this,” his mother said.

“How can that be?”

“Because early this morning,” she explained, “Setsuko’s mother arrived at our door with the news. She knew her daughter was dead in Hiroshima because Setsuko has been visiting her in dreams.”

His mother’s words brought no comfort, only more agitation. He remembered how, when the pika-don came to Hiroshima, a woman’s voice had cried out in his brain and had made him stay under cover while everyone else stood up and was either grievously injured or killed. At first, he had thought it might have been his grandmother’s spirit—then he thought, later, that it must have been Setsuko, urging him to live. Now he knew it was her. Knew it.

Kenshi held back his tears, stood, and said to his father, “We must go at once to Setsuko’s parents, with this bowl, and bring her home.”

When they stepped outside, though only a few minutes had passed, the day had become noticeably drearier. Thick clouds now covered more than half the sky.

The air-raid siren wound down and blasted the all-clear signal. Another false alarm, Kenshi reassured himself. The Hiroshima blast had come out of a perfectly blue and clear sky. Dreary days were good news, in these times. The Americans never dropped bombs if they could not see the ground. Everyone knew this, and took it for a fact.

Passing a row of houses and a Buddhist shrine, Kenshi and his father drew some small comfort from the thickening cloud cover, and Kenshi’s stomach spasms abated ever so slightly. He believed that he might even be able to drink a little water now, and to keep it down. All he needed was a little breathing space. All he needed was for Nagasaki to be safe today.13

Now, however, by aid of jeep-sized portable computers and radar mapping machines, cloud cover was not an obstacle. This time, Kenshi actually heard one of the planes straining to turn around and fly away from the bomb, sounding at one point as if it were flying straight at him.

“Nooo!” he cried out to his father.

|

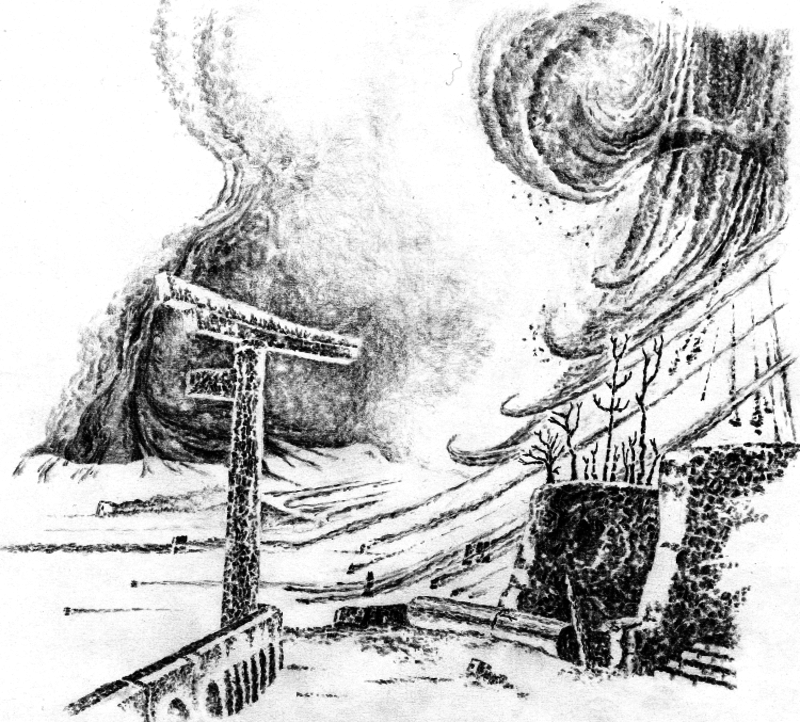

Under the mushroom cloud, within only a few minutes, a mountain of flames taller than the pyramids emerged from Urakami’s “lake of flames.” Just short of one kilometer from the detonation point and the growing cyclone of fire, on an overlook where every living creature perished during the first five seconds, the delicate arch of the Sano Tori Shrine still stood on one leg, with the other leg knocked away. [Illustration: CP.] |

Once again, he was slightly more than three kilometers away from the center of the explosion, on the opposite side of Kompira Hill, near one of the Nagasaki suburb’s most prominent landmarks, a large, oval-shaped stadium. The first time, distance combined with a voice in his head and an instinct to stay away from the windows until the blast wave passed had kept Kenshi alive. This time—in the presence of a bomb up to three times more powerful—what saved Kenshi was not so much a matter of distance and response as the shielding provided by Kompira Hill. Despite the greater fury of the plutonium device, Kenshi found the blast and roar “not so terrible as Hiroshima.” He would not be aware for some time to come how a small mountain (standing only 366 meters high) had shadow-shielded him from the heat rays and shock-cocooned him from the blast. Not very far from where Kenshi and his father stood, at the same radius from the hypocenter—and all within those same few seconds—people down in the shipyard were simultaneously flash-grilled, uplifted, shotgunned by flying glass, and hurled through walls. Only a short distance away, on the other side of Kompira Hill, almost everyone who witnessed the pika was either grievously grilled or dead. Only two miles further north, the people on the streets were now steam and phosphorus, ashes and radioactive fallout.14

Walking through a neighborhood that if not for a mountain would no longer have existed, Kenshi was buffeted by a harsh wind and saw only a few roof tiles loosened. And after the wind had passed, dragonflies still flitted about, seemingly unshaken. But the bones—Setsuko’s bones, to which he had made offerings of flowers and rice and which he had held close to his chest for most of two days—the bomb had ripped the cover from Kenshi’s wedding bowl and flung the bones out of his hands.

“All this way,” Kenshi said to his father, weeping. “All this way, and her bones are scattered who knows where—and to what purpose?”

There was no purpose. No dignity in it, either, Kenshi told himself. No purpose. No dignity. No purpose.

Except, Setsuko might have said, to bear witness.15

|

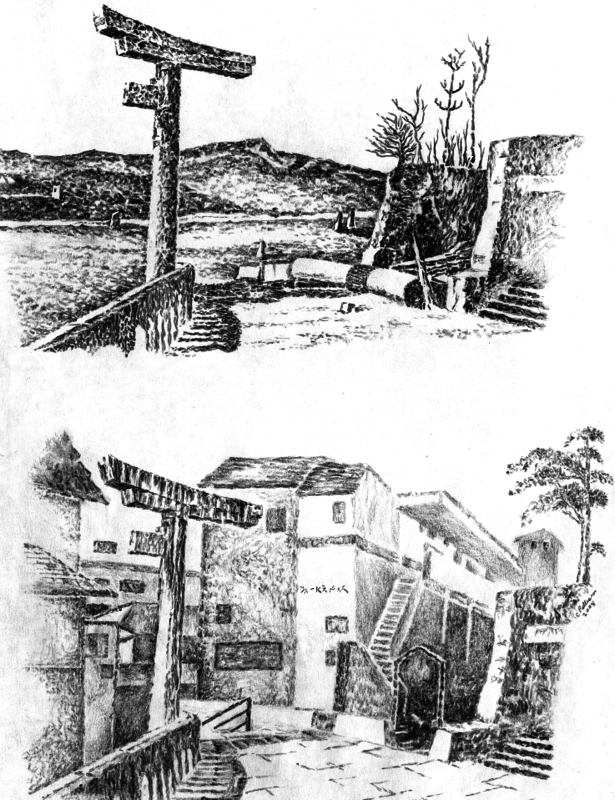

A recovery from symphonic destruction: Upper Nagasaki’s Sano Tori Shrine the day after (in 1945) and in 2010. The difference between then and now is that in 21st century nuclear warfare, there is no guarantee of people coming from outside to rebuild. [Illustration: CP] |

#

WEST OF KOMPIRA HILL, at Kenshi Hirata’s same distance from the hypocenter, fellow Hiroshima survivor Kuniyoshi Sato had been waiting with a crowd of people on the Oohato Pier when, like Kenshi, he survived his second encounter with the atomic bomb. He knew, long before two planes began counting down the last five miles to the new hypocenter, that he would forever be haunted by the image of the man on the train, transporting a bowl-full of his bride’s skull fragments to her parents in Nagasaki.

During the minutes before the bowl of bones was knocked out of Kenshi’s hands, Kuniyoshi Sato prepared to board a ferry that would bring him to the main office of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, on the west bank. He had no way of knowing that across the river, at his destination, fellow engineer and double-survivor Tsutomu Yamaguchi had just been reprimanded for losing contact with him in Hiroshima, and failing to convey him safely to the office. What Sato did know, to a certainty, was that Hiroshima had been destroyed by a single bomb.

“We have heard rumors of this,” a shipyard worker said. “The whole city? One bomb?”

“I saw it,” Sato affirmed. He began to describe the kaleidoscope of strange colors in the pillar of fire and smoke, and the city stamped flat, when a B-29’s engines let out “a high-pitched squeezing noise,” somewhere over Urakami Cathedral, nearly 3.5 kilometers upriver. Instinct moved Sato; and before anyone else on the dock could respond, he dove into the water, and stayed under. A great wing of searing white light cut across the sky. The blastwave pounded down and passed in less than a half second, taking with it almost everyone who had been standing – standing afire on the pier above. The water thoroughly shielded the young engineer, though he did not yet fully comprehend how, or from what.16

#

KENSHI HIRATA had escaped the fire-bombings of Kobe, Osaka, and now, after only three days, his second atomic bomb. It must have seemed to Kenshi that the American B-29 crews were seeking him out personally.

At Nagasaki, he had been completely shielded behind one of his neighborhood’s many hills. The neighborhood itself was mysteriously cocooned against harm. The grasses remained green and the cicadas, though silent, were still alive. The blast wave had done little more than loosen roof tiles, yet it kicked the wedding bowl out of Kenshi’s hands. With his father, he spent the first few minutes after the blast searching for the metal bowl and tracking down every piece of bone they could find, all but oblivious to the cloud rising overhead, and the strange objects falling out of it, including a horse and carriage that crashed into a tree, from which it hung like a Christmas ornament.

When they reached the house, Setsuko’s five-year-old brother appeared at the door, and saw the bowl of bones. The child called out for his parents, noticing that his brother-in-law seemed to be very ill, and scarcely noticing the blizzard of charred paper and clothing that was falling along the street.

The parents gazed with amazement, at Kenshi and the bones.

“Oh, you had a hard time,” Setsuko’s father said, in a calm and uniquely Japanese manner by which multiple feelings and complex messages could be represented by only a few words.

“You had a hard time,” Setsuko’s mother repeated, and Kenshi understood, immediately, the real meaning of this: We are not blaming you. We sympathize.

Then, in one of history’s quintessential examples of how, in Japan, what was said directly and on the surface often conveyed an ocean of meaning, Setsuko’s father said, “You were not registered yet with the city, as a couple. Please don’t worry.”

The words shocked Kenshi. Setsuko’s parents were using a legal technicality as a tool for releasing him from what happened to their daughter and from any obligation to her – past, present, or future. They wished him to move forward with his life and, without looking back, to find love again one day, and to raise a family.

Kenshi did not say anything. He simply left the porch; and even in this silent response, an ocean of emotions was communicated. He was very thankful to the parents for not reproaching him with blame, for instead understanding his situation, understanding his love, his sympathy for Setsuko. And at the same time, their words meant that this was the moment in which their relationship with him was to be terminated. Unspoken, yet said: Because your marriage was not officially registered, we can restart everything. You have your life. We can continue to live together as neighbors, and we will never talk about the contract of marriage.

According to the traditions of Kenshi Hirata’s generation, the wife’s family was permanently bound with the husband’s family because, by tradition, the parents of the wife either encouraged or discouraged the marriage. We don’t blame you, Kenshi, Setsuko’s father had tried to say. Blame the parents for the hastened marriage, and for this sadness. We release you.

“Please don’t worry.” In that simple phrase was hidden a lifetime of meaning.

“The true sadness of the moment was unfathomable to most people,” Kenshi would tell history, as the sixty-fifth anniversary of Setsuko’s death approached. “I felt very sorry for the parents, because they had to say, ‘Please don’t worry.’ I felt so sorry for Setsuko.”

The words, “Please don’t worry” signified, as a rule, the end of all communication between the two families. And yet, after Kenshi Hirata eventually remarried, and after a newspaper report mentioned that his children were fathered by a man exposed twice to radiation, Setsuko’s parents would help him to protect his children from a widespread prejudice that began rising against atomic survivors and their offspring. They helped the Hirata family to disappear, and to stay out of history’s way.

Even during the 1970s, when an American who studied the physical effects of the atomic bombs applied all of his skills as an FBI agent to finding where Kenshi Hirata had fled with his family, he failed to turn up a clue, and eventually died without knowing that Kenshi had disappeared in open view. Setsuko’s family, and Kenshi’s parents, and all of their neighbors, would protect his identity and the identities of his children so well that he never had to move from the neighborhood.

In the end, the same man who slept on the ground where his wife had been vaporized in Hiroshima, desiring only that her spirit would not feel abandoned, never lived more than half of a city block from the stone pinnacle where Setsuko’s parents had buried her bones. Even after sixty-five years passed, Kenshi continued to make offerings of water at the shrine, keeping his own private promise that Setsuko would never be left behind, or forgotten.17

#

ELSEWHERE ALONG THE FRINGE of Ground Zero, Takashi (Paul) Nagai had been one of the few physicians to survive the much more powerful Nagasaki bomb. During the year in which Setsuko’s parents built a shrine on the fringe, Dr. Nagai established a research outpost deep within the fringe, overlooking the hypocenter. There, he recorded short-lived mutations in gardenias and clover during a gradual but labored recovery of nature, in a region where the gamma rays, neutron spray, and fallout dosing were many multiples greater than anything to which Kenshi Hirata had been exposed. It became possible for the physician to believe that nature would heal the wound in the Earth, and that everything might somehow be okay; but he had grave doubts. In a tunnel air raid shelter nearer the hypocenter than Dr. Nagai’s makeshift monitoring station, a young mother-to-be had already learned that everything was going to be “far, far from okay.” At Moment Zero, she was underground, double-checking a small hoard of emergency rations and clothing for her relatives, in the house above. In barely more than a lightning bolt’s lifespan there was no longer a house above, nor any living thing, and the Nagasaki gamma-shine had reached into the shelter, and into her womb.

Whether or not he was reading a cautionary tale into a merely coincidental line of ancient scripture, it was plain from what Dr. Nagai witnessed in the deformed flowers, and in what came afterwards, that too much of what happened under the atomic bombs echoed a prophecy recorded in the twenty-fourth chapter of Matthew: “But woe to those who are with child and those who are nursing babies in those days.”

For the woman in the shelter, the developmental pathway that led to growth of the brain’s frontal lobes was cut short. Random facial features and major pathways to limb development were sped up and slowed down.

The child was born male, with scarcely more than an ancestral, reptilian framework of a brain, abandoned in mid-construction. His arms and legs were as the limbs of an amphibian, and he moved much in the manner of the overgrown salamanders that waddled on their bellies across the pre-Triassic/Jurassic mudflats of central Japan’s Gifu Prefecture.

As recorded by Nagasaki memorialist Kyoko Hayashi, “When he grew to twelve or thirteen, he developed sexual desires. Not knowing how to control himself, he threw himself on his mother as led by his instincts.”

Still loving the being as a child, but perplexed, the mother harnessed him and leashed him to a pillar in the living room, where he howled unbearably like a wild beast and tried to gnaw through the leash. A doctor finally suggested that he needed to be calmed down like a gelded animal, and near the end, she consented to surgical removal of the boy’s testicles.

In her warning to future generations, Hayashi would write that, after his gelding, the child of gamma rays and fallout-borne alpha particles, “became a ‘good’ boy with dulled responses, a quiet boy who did no harm to healthy people. In the spring of his fifteenth year, he was overcome by intense convulsions, and died after quivering all day long. The only human-like response the boy had ever demonstrated was his unrestrained sexual desire before the operation.”18

#

IN THE SUBURBS of Nagasaki, an entire neighborhood helped Kenshi Hirata to hide in plain sight, and to rebuild his life. Setsuko Hirata’s parents chose to regard the rebuilding as a tribute of their daughter’s love for Kenshi and to what she would have wished for him. After their sorrowful release of Kenshi, love had come again for him. By 1955, Kenshi was remarried, and had become the father of two healthy children. After the Mitsubishi Corporation allowed its records of his survival report to be published by an American journalist in 1957, he had no choice but to disappear with his wife and their “contaminated” offspring. Setsuko’s family participated in the hiding of the Hirata family’s identity so well that the children themselves did not know exactly who they were.

Kenshi’s daughter, Saeko, grew up to study journalism in college and was working for the Nagasaki Broadcasting Corporation when she learned, quite by accident, that she was born of what had turned out to be her father’s second marriage. Though curious, and wanting answers, a young Japanese woman could not, in those days, simply ask her father what happened. Instead, she asked her mother, who explained for the first time about the remarriage, and about her father’s first wife, who had died in a terrible fire-bombing. Saeko’s mother did not mention “double hibakusha,” or even the word, “atomic.” She told a strange story about how the second true love of Kenshi Hirata’s life was actually his first love, and how his first love (Setsuko) was actually his second.

At age twenty-three, about the time Japan engaged America in war, Saeko’s father had been sent to the battlefield. He returned with his legs all but destroyed by malnutrition and disease, and was thereafter assigned to a desk job.

Before the war, Saeko’s mother, and Setsuko, and Kenshi had grown up in the same neighborhood. Kenshi knew Saeko’s mother from the time they were toddlers, and almost from the start they had become inseparable childhood sweethearts. Yet when Kenshi approached Saeko’s grandfather in 1943 with a proposal for his daughter’s hand in marriage, he was refused. No one knew for certain why the father had blocked the marriage; but in the militaristic atmosphere of the day, men fighting and dying in the Pacific arena gained honor, while a man at home safely behind an accountant’s desk would likely have been viewed with dishonor, even if the desk job was born of Pacific injuries.

Two years after the refusal, love came to Kenshi Hirata a second time, and he married Setsuko, and brought her from Nagasaki to the city where she died.

More than a year after Kenshi lost Setsuko and Japan lost the war, Saeko’s grandfather had a change of heart and allowed Kenshi to marry her mother. Saeko learned that Kenshi wept and “confessed” to her mother everything that had happened to him, including the story of Setsuko, and how he recovered some of her bones and saw them placed in a tomb that he continued to visit.

Saeko’s mother had told the story – minus the part about her father sleeping on Setsuko’s radioactive grave in Hiroshima, minus mention of the city’s name and the part about the second atomic bomb – noting that she believed Kenshi had needed to “confess,” out of some inner shame. But his first love did not hold him to any blame at all for loving Setsuko, or for losing her to a fate that seemed as much beyond all human control as it was beyond all prior human experience. Saeko’s mother explained that she had long ago accepted these events. Indeed, it occurred to her mother that had Grandfather allowed her to become Kenshi’s first wife, fate would have dealt them all a very different hand. She came to regard Setsuko as a sister, as the gentle kind-hearted woman who traveled to a doomed city and died in her place. And so she made regular visits to Setsuko’s tomb, honoring her.19

#

IN JANUARY 2010, one of Kenshi Hirata’s Mitsubishi colleagues, a fellow double-atomic-bomb-survivor named Tsutomu Yamaguchi, succumbed to what appeared to be the fate of most hibakusha: a prolonged battle with cancer. He survived years with a form of stomach cancer that was often lethal within six months of discovery; and long ahead of the cancer, as far back as his daughter Toshiko could remember, his hair fell out every summer and the flash-burn scars seemed to temporarily worsen, and two or three times each winter, a simple common cold progressed to pneumonia.

In a suburb of Nagasaki, Kenshi’s daughter Saeko was, at the time of Yamaguchi’s passing, working for a TV news organization. She was both moved and fascinated by the story of a double hibakusha who had lived nearby. She did not know, yet, that another survivor of both atomic bombs lived much nearer, and that he was her own father.

About February 25, 2010, documentary film-makers Hidetaka Inazuka and Hideo Nakamura (who had befriended Tsutomu Yamaguchi and taken up the search for the Hirata family), finally located Saeko, and gently revealed to her who her father had been.

“Had been,” it turned out, was not the correct term. Kenshi Hirata was still alive. He was ninety-one years old; but like many of the survivors, he did not want to remember. Even those who did speak of it, as Yamaguchi had spoken, did so with great difficulty. Especially, Kenshi did not want to speak about Setsuko.

Nagasaki historian Tomoko Maekawa—who was doing all that was humanly possible to record and archive the stories of survivors before their generation vanished utterly—had volunteered for one of the world’s most heart-wrenching jobs. She understood why Kenshi Hirata, like so many others, wished not to remember.

“When I listen to the stories of the survivors,” the historian explained, “I can see that it is very tough for them—very saddening to remember and to tell of their experiences, almost as if they are bleeding from their hearts when they speak about it. I do not think I would be able to talk about it as they do if I experienced a similar thing.”

Only slowly, between March and August of 2010, did Kenshi Hirata begin to reveal what he had hoped, for most of his life, no one would actually learn about him. He did not want to remember.

“Being a double survivor was a shameful dishonor,” he said enigmatically; and for many weeks afterward it appeared that he would never say anything more about it. Hideo Nakamura and historian Tomoko Maekawa tried to comprehend what sort of survivor’s guilt must have accompanied being shielded from the atomic bomb twice while his wife and more than 200,000 people died all around him.

In time, Kenshi explained that part of his shame came from the demands of Japanese society during the 1940s. Even remarriage of a widower, in those times, came under the shadow of “the district gossip committee,” and was considered a dishonorable act that somehow stained the children: “So, I was not only trying to protect my children from radiation discrimination; I did not want society to carry rumors and scandals about my daughter as a second marriage daughter. And so I eliminated the secondness of the marriage.”

“How can you keep it in your heart?” Saeko asked her father. “I’m amazed that you kept it secret, like a clam, for sixty-five years.”

“I am relieved to finally speak out,” Kenshi said.

“I am sorry for him to now have to expose this secret after so many years,” Saeko recorded for history. “In that inferno, my father was trying to find his wife. Sacrificing everything – without complaining about the pain – to find her. I am amazed. For two full days, he was searching for his wife. This is something he has been hiding for a long time. But I am delighted to see my more real father.”

“I did not wish to be a double hibakusha,” Kenshi emphasized. “This is not my wish. It just happened, because they built the bombs. So, everyone has to think about it. If we really think about each other, this should not be. Nuclear arms are not [compatible] with civilization. I think such a thing should not be existing.”

And he concluded, “This is the first and last time I will speak to the world about it. These are my last words on the subject. Do with them what you may.”20

Charles Pellegrino is the author of twenty books, including the New York Times bestseller Her Name, Titanic, and Ghosts of

the Titanic, which James Cameron used as sources for his blockbuster movie Titanic and his 3D Imax film Ghosts of the Abyss. With Brookhaven National Laboratory physicist James Powell, he designed the Valkyrie anti-proton-triggered-fusion configuration for space flight (introduced in AAAS 1986 Symposium Proceedings and animated in 2009 by James Cameron for the Avatar films, in which Pellegrino served as a scientific consultant). With Powell he also worked closely with Senator Spark Matsunaga on the U.S./Russia Space Cooperation Initiative during the 1980s, as a means of helping to reduce the probability of nuclear war. Pellegrino is probably best known as the scientist whose “dinosaur biomorph recipe” became the scientific basis for the Jurassic Park series.

The second American edition of “Last Train” (other editions have already been published in a dozen languages since 2010, most recently in Arabic and Chinese) will be published by Rowman & Littlefield in August 2015, under the title: To Hell and Back: The Last Train from Hiroshima.

Recommended citation: Charles Pellegrino, “Surviving the Last Train From Hiroshima: The Poignant Case of a Double Hibakusha”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 26, No. 4, June 29, 2015.

Related articles

• Vera Mackie, Fukushima, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Maralingan

• Daniela Tan, Literature and The Trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

• Robert Jacobs, The Radiation That Makes People Invisible: A Global Hibakusha Perspective

• Mark Selden, Bombs Bursting in Air: State and citizen responses to the US firebombing and Atomic bombing of Japan

• Sawada Shoji, Scientists and Research on the Effects of Radiation Exposure: From Hiroshima to Fukushima

Notes

1 The first hundred milliseconds over Hiroshima: The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, internal report, Chairman’s Office, June 30, 1946, pp. 1–33; E. Ishikawa, et al., pp. 21–79. The next half-second, throughout Hiroshima, was reconstructed in accordance with U.S. high-speed film footage of tests near and below 15 kilotons, on structures and animals. Tests: Hot Shot, How, Sugar, Fizeau, Fox, and Stokes; at Bikini Atoll, Test Able; at Enewatak Atoll, Tests Seminole and Sequoia. Collectively, footage and results covered varying distances from the hypocenters. NOTE: The direction of neutrinos through Setsuko’s body is determined, not by a straight-line path from the bomb’s detonation point through the Earth’s core, but via an angle dictated by the location of the Hirata house, relative to the bomb (location verified by the Hirata family, 2010).

2 Robert Trumbull, Nine who Survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki (N.Y., Dutton, 1957), p. 24, referenced Kenshi Hirata’s prior near miss of the Osaka and Kobe fire-bombings of March 13 and 17, 1945 [p. 38]. Mr. Hirata at Hiroshima, Aug. 6, 1945: 8/9/55, translation of K. Hirata report for Mitsubishi, Nagasaki, in Trumbull, pp. 23–27, 34–35, 64–71, 76; Norman Cousins, personal communication (1987); Henshi Hirata and family, interviews via Hideo Nakamura and Hidetaka Inazuka (2010). On the Hiroshima bomb as a 10–12.5 kiloton “disappointment” (as opposed to 20 kilotons officially announced by President Truman): Smithsonian Timeline #2—The 509th (Composite Group), The Hiroshima Mission, p. 3: “8/6/45; 8:15:17–8:16AM—Little Boy exploded at an altitude of 1,890 feet above the target. Yield was equivalent to 12,500 tons of TNT.” (For comparison, the Nagasaki bomb was in the range of 24 kt (nomenclature, Sigurddson, Sheffield, Shoemaker, Pellegrino based on Nagasaki yield, in, “Ghosts of Vesuvius,” Harper, N.Y., 2004, p 62.)

3 See note 2.

4 Implosive effects, heavy machinery, air-filled storm drains “vacuumed” up through the pavement, in U.S. Strategic Bombing Surveys, Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Washington D.C., June 30, 1946). Tsutomu Yamaguchi pulled by a collapsing shock bubble (personal communication, 2008 and unpublished report, “I Live to Tell My Story,” translated by Hideo Nakamura, 2009). Carbonization of people: Testimony K. Hirata – “shadow people” and “statue people,” July 2010; testimony of Dr. Hiroshi Sawachika, p. 1; Japan Society Conference 5/21/10; testimony of Takehisha Yamamoto, p. 2 (and personal communication, 2010). Shadows and ash bodies: Yoji Matsumoto, in personal communication and via his daughter Kae Matsumoto (2010); testimony Setsuko Thurlow, May 2015. Conditions and views near the Hirata House: Morimoto (Mitsubishi account, 1945, 1946), translated in R. Trumbull (see note 2).

5 See notes 1, 4.

6 Residual radiation effects at the location of Kenshi Hirata’s home in Hiroshima: E. Ishikawa, et al, Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings. Originally published in Japanese, (Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 1979); English Translation, (N.Y., Basic Books, 1981), pp. 73–79.

7 See note 2. Further details about the first night, including planes and towers of smoke: Sumiko Kirihara’s family, in Youth Division of Soka Gakkai, Cries for Peace, (The Japan Times, 1978), pp. 78–80; Masahiro Sasaki, personal communication (2008).

8 “Statue people,” see note 2.

9 Kenshi Hirata and the soldiers, see notes 2, 4.

10 See notes 2, 6. Notes on the train that picked up speed, fanning the flames as it raced past Kaitaichi Station toward a collision with a truck: Nancy (Minami) Cantwell and the Hiroshima nurses of Dr. Fujii’s crew (personal communication, 2008). Their first rescue effort was in fact at the site of this famous train wreck. Some details on flavorings added to extreme rations: N. Cousins in personal communication (1987); Tokusaburo Nagai in personal communication (2008); Hiroko Nakamoto in personal communication (2010) and in her book, My Japan: 1930–1951 (N.Y., McGraw Hill, 1970), pp. 50–51.

11 Kuniyoshi Sato was a friend of fellow double-survivor Tsutomu Yamaguchi, who affirmed (first during interview, July 19, 2008, p. 9), that it was indeed Kenshi Hirata seen by Mr. Sato on the train from Hiroshima. K. Sato’s description of the man on the train, bringing his recent bride’s remains in a helmet-shaped bowl to her parents in Nagasaki, and Sato’s double-survival: Translations [in] Richard L. Parry, London Times (August 6, 2005). K. Sato’s story of survival in Nagasaki was recorded and translated by H. Nakamura, personal communication, 2010. On a cremated body full of broken glass, and the people Junichi found in a bank near the hypocenter: The Asahi Shimbun Messages from Hibakusha Project (accessible via C. Pellegrino home page and here); Junichi Kaneshige, Case 20003, 2010.

12 Kenshi Hirata, “the night train”: See note 2.

13 See note 2.

14 On the greater power of the Nagasaki bomb, including flash-dessication of leaves out to a radius of 80 km (compared to 12 km for Hiroshima): M. Shiotsuki, “Doctor at Nagasaki,” Koesi, Tokyo (1987), p108; Clarence Graham (radius 63km) in T. Brokaw, “The Greatest Generation Speaks,” Random House, N.Y. (2005), Ch. 1. See note 1.

15 See note 2 (Trumbull, p. 119). Note: Norman Cousins was quite familiar with the Hirata history up to the point of Hirata’s disappearance about 1955 (personal communication, 1987).

16 Kuniyoshi Sato’s late arrival at the ferry, for the meeting at which Tsutomu Yamaguchi was being upbraided for having lost track of engineer K. Sato in Hiroshima: Interview, Aug 6, 2005, R.L. Parry, The Times of London (chapter 5, footnote 18). T. Yamaguchi on K. Sato, personal communication July 2008. Events at the pier, on the opposite side of the river from Yamaguchi: K. Sato interview, Hideo Nakamura, 2010.

17 Further notes related to the first three minutes: Nagano in Nagasaki Museum Archives, Testimony of Atomic Bomb Survivors #14. Dr. Nagai (on the Urakami firestorm), in The Bells of Nagasaki, pp. 28, 32, 41; Nishioka, in Trumbull, p.113. The Nagai children, Dr. Akizuki and other eyewitnesses described a large variety of objects raining down from the cloud, some being whipped up into the air by cyclones of flame springing from an immense lake of fire, as in Tasuichiro Akizuki, Nagasaki 1945 (London, Quartet Books, 1981), p. 27. Tamotsu Eguchi, in “Nagasaki,” in Hiroshima in Memoriam and Today (Hitoshi Takayama, editor; Peace Resource Ctr., U.S., the Hamat Group, Hiroshima, 2000), pp. 58–60; Asahi Shimbun (Charlespellegrino.com), “Hibakusha Voices,” Disk #6, Witness #256. Kenshi Hirata and Setsuko’s family: Interviews with Kenshi Hirata, his daughter Saeko, and Setsuko Hirata’s brother, July 2010 (Hideo Nakamura, Hidetaka Inazuka).

18 Dr. Nagai: Tokusaburo Nagai, personal communication (2008); discussions with Father Mervyn Fernando (Subhodi Institute, Sri Lanka), about what Dr. Nagai was trying to learn and to teach (2007). The mother whose unborn son was fiercely irradiated in the womb, and the incomparable tragedy that followed, is only one episode in Nagasaki memorialist Hayashi Kyoko’s essay, “Masks of Whatchamacallit,” translated by Kyoko Selden The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 2014.

19 Kenshi Hirata, his daughter Saeko, and what happened after Kenshi disappeared (about 1955) to protect his family from anti-hibakusha discrimination [pp. 334–35]: Interviews with Kenshi Hirata, Saeko Hirata, and Setsuko’s brother, by Hideo Nakamura and Hidetaka Inazuka, March, July, 2010.

20 Tsutomu Yamaguchi and his family, personal communication, 2008 – 2015. Kenshi Hirata, after the war: see note 19. Tomoko Maekawa, personal communication (2010, 2014), Hideo Nakamura, Hidetaka Inazuka, personal communication, 2010 – present.