|

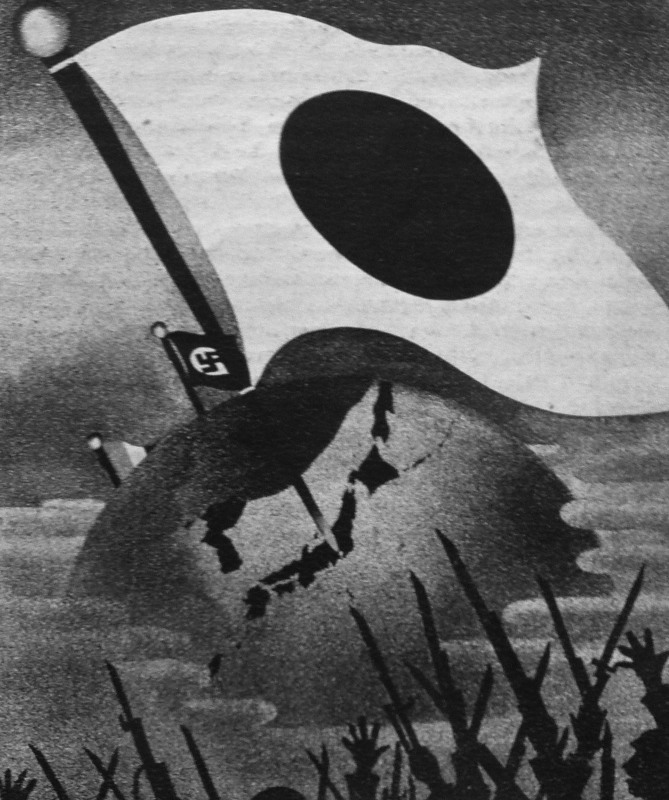

Figure 1. The alliance. Draft of poster by 15-year-old Japanese boy from exhibition of drawings of Japanese pupils, 1941/1942. |

In three articles published in 2013/14 in this journal, Brian Victoria and Karl Baier shed light on the relationship of Japanese Buddhists, in particular of Daisetz Suzuki, to German National Socialism, and, in turn, of German National Socialism to Buddhism, in particular to Japanese Zen Buddhism and to the history of the Japanese samurai.1 All three articles are highly commendable because these relations were hitherto nearly unknown and provide interesting insight into the cultural ties between Germany and Japan in the years of the “axis”. I would like to reexamine some of the assertions made in these articles, to present additional details and introduce certain sources, which neither Victoria nor Baier, nor other authors quoted by them, had utilized. I discovered these sources while conducting research for a comprehensive study on German-Japanese cultural relations between 1933 and 1945 which was published recently.2

Remarks on Suzuki’s report on a trip to Germany in 1936

I would like to begin with some remarks about Suzuki’s report on a trip to Germany in October 1936. Prior to Victoria’s discovery of this report, the fact that Suzuki had visited Nazi Germany and wrote about his visit was hardly known.3 Victoria has shown that the report reveals certain sympathies on Suzuki’s part for National Socialism and suggests that these sympathies might have been based on socialist inclinations which Suzuki had felt in his youth. It may be interesting to note that the report also reveals Suzuki’s lack of knowledge regarding Germany and German history in general and National Socialism in particular when he arrived there and shows that he merely reproduced what he heard and saw. One example of his unfamiliarity with Germany is his interpretation of the so-called Hitler salute as a sign of Hitler’s popularity. In fact, this salute was quite common since the National Socialists had come to power and even mandatary for representatives of the government and the Nazi party on official occasions. Suzuki’s remarks on the anti-Jewish policy of the Nazis serve as another example. They obviously repeat what followers of the Nazi movement told him – namely, that Jews had “rushed into Germany like a flood” after World War I, that they were a non-indigenous “parasitic people“ who lacked any ability to develop a “connection to the land”, and that “they monopolized profits in the commercial sector while utilizing their power in the political arena solely to advance their own interests.”4 All these statements were anti-Semitic clichés that had been rampant in Germany even before 1933 and blatantly distorted historical and social facts. In truth, in the early 1930s, the majority of German Jews belonged to families that had been living in Germany for generations – in many cases, even for centuries. They were assimilated culturally and successful economically and no longer perceived their Jewishness as an ethnic feature, but, if at all, as a religious or cultural one. They saw themselves as Germans. But they possessed little political power and observed with mixed feelings the increasing immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe into Germany – a trend which had already begun at the end of the 19th century. Nevertheless, for some time after 1933, many German Jews continued to believe that the revocation of their equality before the law and their segregation from German society would be impossible, even though the National Socialist Regime had begun its relentless pursuit of such a policy. As a consequence, many Jews did not leave Germany, while it was possible, after the onset of National Socialist rule. Suzuki’s encounter with Jewish émigrés in London must have given him an idea of what expulsion from Germany meant for them. His view, however, was that the expulsion itself was “an action taken in self-defense”, and thus justified.5

|

|

| Figure 2. Nogi, the last samurai: the Japanese hero of Port Arthur, Ronald E. Strunk. | Figure 3. “‘Spirit of your spirit’: how Japanese women fight at home for victory”. |

Some remarks on National Socialism and Buddhism

Obviously, Suzuki did not meet prominent representatives of the National Socialist regime nor scholars and intellectuals during his visit to Germany in 1936. In addition, the German press, as far as is known, did not take note of his stay. At that time, Suzuki’s level of familiarity in Germany was limited to scholars of religion, and only a few of his essays had been translated into German.6 Victoria does not refer to these facts, nor does he mention that the German press began to show an increasing interest in Japan in general and Buddhism in particular soon after the Nazis’ rise to power. This interest was based on the desire to understand Japan’s coup d’état in establishing Manchoukuo in 1931 and subsequent conflicts thereafter. Even more important was the rapprochement between Germany and Japan which began in 1934 and was underscored by the December 1936 German-Japanese anti-Comintern pact (Antikominterpakt). By means of essays and books, photographs and films, screen plays and exhibitions, the Germans were to be familiarized mentally and emotionally with their new ally in the Far East. (See figures 2, 3, 4 and 5.)

One strategy used by many of the publications in question was the construction of alleged affinities and similarities between Germany and Japan – historical, cultural, and political kinships. Similarities were seen to exist between Shintoism and Japanese national ethics and Germanic pagan religions and ethics; in a common respect for ancestors; in placing the importance of the community above that of the individual; and in centering society and political structures around the Tenno or the Führer respectively. Furthermore, both societies were viewed as being similar in their rejection of liberalism, individualism, democracy, private capitalism, and communism as well as in their commitment to common ideas of race and hereditary health. Both nations were also depicted as having a common need for expansion, as both were seen to be suffering from a lack of “living space” (Lebensraum). Occasionally, descriptions of the alleged kinship between the two peoples even went so far as to suggest certain racial links.7

From very early on National Socialist authors showed special interest in Buddhism, mainly because of their race theory, particularly their assumptions regarding Aryans, whom they saw as the ancestors of the Germanic peoples. H.F.K. Günther, the leading National Socialist theorist dealing with racial questions, depicted Buddha as an Aryan, probably light-skinned and blue eyed, and explained the teachings of Buddha as being “a life teaching for individual nobles” („Lebenslehre für einzelne Edelinge”), demanding “self-discipline and inner superiority” („große Selbstzucht und innere Überlegenheit”).8 A National Socialist indologist described Buddha as an Aryan hero, as a “warrior yogi” („Kriegeryogi“), and presented his early followers as examples of “passive heroism”.9

|

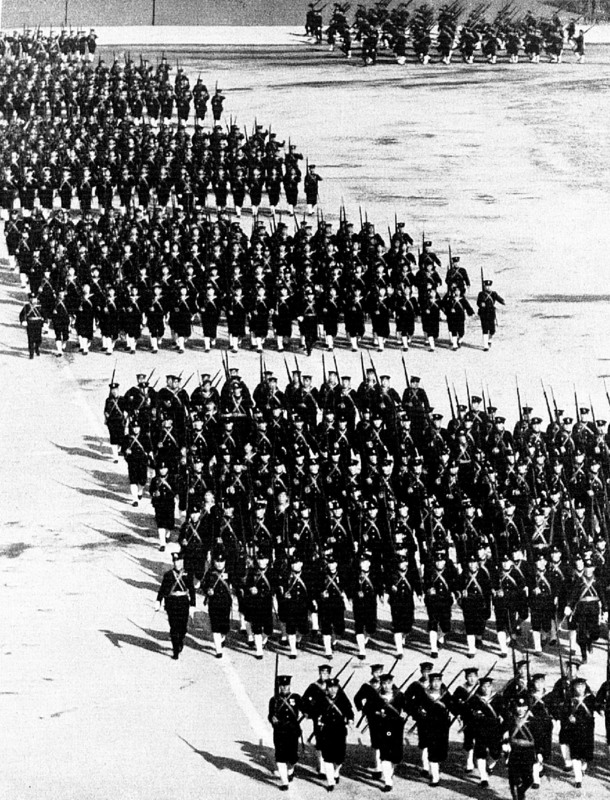

Figure 6. Japanese soldiers in German press, circa 1940-43. |

Ideologists of National Socialism held Japanese Zen Buddhism in particularly high regard. They described it as a “path of utmost discipline and self-denying commitment” to “inner concentration and meditative contemplation” („Weg härtester Zucht und selbstverleugnender Hingabe“ zu „innerer Sammlung und Versenkung”), but perceived the contemplation in question as one “leading to action” („Tatversenkung”) which was “excellently suited to the art of combat” and which gave fighting its “unconquerable force” („unbezwingliche Gewalt“). This interpretation of Zen Buddhism was inextricably linked to an affirmation of the existing (outer) world, including that of fighting („Jasagen zum Weltgegebenen, ja zum Kampfe“). Thus, Zen Buddhism was not perceived as a spiritual phenomenon but as a prerequisite state of mind for the “most outstanding type of warrior”; above all, for the “aristocracy of warriors” (für einen „hervorragenden Kriegertyp“, ja „Kriegeradel“) – that is, for the samurai. It was also treated as an integral part of a “folkish-national ethos”.10

Victoria does not deal with the vast number of German works on Japan that were published in the 1930s, nor does he deal with the increasing German interest in Buddhism in general and Zen Buddhism in particular. Similarly, he devotes no attention to the small group of Buddhists who lived in Germany in the early 1930s and whose spokesmen showed a surprisingly strong affinity to National Socialism.11 He treats only one aspect of the Nationalist Socialist interest in Japan, namely the explicit and early interest in the samurai, whose history is closely connected to that of Zen Buddhism. He rightly mentions a series of articles about the samurai which was published by the SS periodical The Black Corps (Das Schwarze Korps) in the spring of 1936. These articles suggested that the samurai had not only displayed similarities to medieval Germanic knights but also possessed characteristics embodied in the political ideology of National Socialism, such as “an ethos of chivalry and masculinity” („ritterlich-männliche Gesinnung“), a “strong emphasis on obedience and loyalty” („starke Betonung des Gehorsams und der Treue“), and an “ideal principle of leadership” („ideales Führerprinzip“)12. It is worth noting that the author of the articles, Heinz Corazza as early as 1935 published a book about Japan in which he drew strong parallels between Japan and National Socialist Germany.13

On one point regarding the relationship between the SS and the samurai, Victoria’s observations may be somewhat inaccurate. He remarks that Heinrich Himmler, leader of the SS, “planned to model the SS on the Japanese samurai”, and “received permission from Adolf Hitler” to do so.14 This belief, which appears to be an idée fixe of Victoria, is based on a conversation between Himmler and Hitler quoted in Peter Longerich’s biography of Himmler.15 Victoria not only misdates this notice by stating that it was written in 1937 (it was written in November 1935), but also exaggerates its importance. Himmler noted that he presented Hitler with the idea “that the SS should one day become the German samurai”, and that Hitler agreed.16 In my understanding this does not mean that Himmler presented a solid plan to Hitler, but merely referred to the samurai in a general sense rather than as a model. Furthermore, it seems that Hitler concurred only generally but did not grant any official consent. If Himmler had had a solid plan, other sources would have reported it, too.

|

|

|

| Figure 8. Japanese army. | Figure 9. Japanese infantry. | Figure 10. Japanese navy. |

| From German press, circa 1940-43. | ||

National Socialism and Buddhism during the war

Victoria indicates correctly that after the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 main works of Suzuki were translated into German: in 1939 his Introduction to Zen Buddhism, in 1941 Zen Buddhism and its Influence on Japanese culture17; in the same year, the second edition of the German translation of Introduction to Zen Buddhism appeared. These translations were consistent with the image that National Socialist authors and German Buddhists had previously created of Japan in general and of Buddhism in particular. Thus the South German edition of the central organ of the NSDAP, the Völkischer Beobachter, quoted at length from Suzuki’s book on Zen and Japanese culture, placing special emphasis on the samurai’s readiness to die.18

The translations of Suzuki’s writings were part of a flood of publications on Japan that were appearing in Germany during the war.19 Victoria mentions only one of them, Count Albrecht von Urach’s booklet “On the secret of Japanese power” („Vom Geheimnis japanischer Kraft”), which was printed in several editions comprising 600,000 copies altogether.20 It must be pointed out that numerous other books and articles on Japan were published as were translations of Japanese heroic literature, films, screen plays, poems, and even musical compositions. The goal was to increase empathy among the Germans towards their ally in the Far East and, above all, to present the morale of Japanese soldiers as an example for German soldiers. A Japanese article quoted by Victoria asserts that the translations of Suzuki’s writings exerted a deep influence on the military spirit of National Socialist Germany.21 This assertion merits reexamination. According to a classified report of the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst) of the SS of August 1942, the depiction of the Japanese “as something akin to ‘Super-Germans’” („sozusagen als `Germane im Quadrat`”) had a rather daunting effect on German soldiers, for whom these depictions were to serve as examples. Accounts dealing with Japanese swimmers who removed mines near Hong Kong or describing Japanese kamikaze pilots who, in total disregard for their own life, crashed their bomb laden planes onto enemy vessels, the report said, produced “a kind of inferiority complex” („so etwas wie Minderwertigkeitskomplexe”) among Germans and failed to do justice to the achievements of German soldiers. The Security Service thus concluded that the image of Japan presented to “fellow Germans” („deutsche Volksgenossen”) was “in need of correction, mainly in the form of a clear and positive comparison to [Germany’s] own achievements and values.”22 In the summer of 1944, however, in an address delivered to high ranking SS officials in Sonthofen (Bavaria), Himmler again expressed his respect for the bravery of Japanese soldiers, who had no fear of death, but went on to say “that we, the world’s oldest civilized people and its oldest warrior people, do not need a foreign race to provide us with examples or to serve as role models. The history of German soldiers and German women can most certainly present us with as many numerous examples and role models as can that of the Japanese, Chinese, or any other people.”23 (See figure 11.) Praise of Japan disappeared in publications of the SS. In other publications it continued but was superseded everywhere by depictions of the Germanic heroes of the Edda, the medieval Nibelungenlied, and the myth of Walhall. These were now to provide the dominant role models.24

|

Figure 11. “‘Jibaku’ for the future of his country: determined to die, the pilot ties the sun banner to his forehead and in an act of self-annihilation will dive his aircraft and payload into the enemy battleship.” One of the last images of German propaganda for Japan, 1944. |

Count Dürckheim’s path to Japan

Victoria and Baier must both be commended for their in-depth treatment of the biography and writings of Count Karlfried von Dürckheim, a German who propagated National Socialism in Japan between 1938 and 1945. Baier traced Dürckheim’s intellectual development, in particular his völkisch religiosity and his involvement with the so-called Bureau Ribbentrop, a private foreign office of sorts which Hitler’s expert on international affairs, Joachim v. Ribbentrop, maintained before he became Foreign Minister. Victoria describes Dürckheim’s contacts to Suzuki in Japan. As to the reasons why Dürckheim went to Japan in 1938, Victoria and Baier rely on what Dürckheim himself later wrote and said: that he had been dismissed without notice in 1936 as “politically unacceptable” („politisch untragbar”) at the instigation of Göring25, or that his removal from the Bureau Ribbentrop and ensuing “deportation” to the Far East were due to the discovery that his maternal grandmother had been Jewish.26

In reality, Dürckheim was not dismissed without notice, nor was his dismissal instigated by Göring. Moreover, his partly Jewish family background was not the reason why his work in Ribbentrop’s office ended; and, contrary to Victoria’s assumption, neither did the establishment of closer ties between Germany and Japan in the second half of the 1930s have anything to do with Dürckheim’s journey to the Far East.27 The whole affair was much more trivial. Prior to his engagement by Ribbentrop, Dürckheim had been professor of psychology and philosophy at the College of Education in Kiel, from which he was only on leave during his stay in Berlin. His contract to Ribbentrop ended at the end of 1937, and he could have easily returned to Kiel. But after his involvement in foreign affairs, he wanted to remain in the German capital and be entrusted with more important duties than the education of teachers for primary schools. As Ribbentrop obviously did not intend to take him with him in the Foreign Office when he became foreign minister in February 1938, Dürckheim wanted to obtain a professorship in foreign studies (Auslandskunde) and go on a study tour of East Asia in order to prepare. Apparently, he succeeded in winning Ribbentrop’s support for this idea and in obtaining the promise that his study tour would be funded by the Bureau Ribbentrop. Ribbentrop may have agreed on the assumption that a College of Foreign Studies (Auslandshochschule), which had been under consideration for some years, would soon be established and that Dürckheim could be transferred there. For several reasons, however, this turned out to be surprisingly difficult. A dispute between the Bureau Ribbentrop, the ministry of Education, many of Dürckheim’s supporters, and Dürckheim himself ended after several months when it was agreed that Dürckheim would be granted leave for an additional year to conduct research in Japan to be funded by Ribbentrop and subsequently be engaged in the Foreign Office or would return to Kiel.

The German Embassy in Tokyo was not involved in this decision, and may not have been quite enthusiastic about Dürckheim’s coming to Japan. According to his own statements, made after the war, Dürckheim acted as a “cultural envoy” (Kulturdiplomat) in Japan. Victoria has given credence to these statements and linked them to a general discussion of the meaning and role of “culture” in National Socialism.28 His arguments are largely correct. Dürckheim, however, did not have diplomatic status when he arrived in Japan, and “cultural envoys” were unknown to the German Foreign Service. Instead, in every major German embassy one diplomat was in charge of cultural relations to the respective country. In Tokyo until the end of 1938, that was the brief of ambassadorial counselor (Gesandtschaftsrat) Hans Kolb.29 Nevertheless it may true be that, as Dürckheim later wrote, the embassy informed Daisetz Suzuki about Dürckheim’s arrival and Suzuki came to the embassy to meet him; however, embassy reports that have been preserved do not confirm this. It is worth mentioning that Dürckheim was not the first German scholar to visit Japan to campaign for the new Germany and meet prominent Buddhists. He was preceded in 1936-37 by the famous educator Eduard Spranger from Berlin University. Spranger had lectured throughout Japan and met prominent Buddhists, among whom Suzuki may have been included.30 Walter Donat, from the Japanese-German Cultural Institute in Tokyo, had accompanied Spranger. The Institute was a bi-national institution founded in 1926, and Donat had been serving as the Institute’s German secretary general since the beginning of 1937. He was a fervent supporter of National Socialism, leader of the Japanese chapter of the National Socialist Teachers’ Association (Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund) and strove to establish ties to Japanese scholars, intellectuals and artists. He may have been the one who introduced Suzuki and Dürckheim to each other. Suzuki knew Donat, as is mentioned in Suzuki’s diary, from which Victoria quotes.

Dürckheim stayed in Japan from mid-1938 to the beginning of 1939 and then returned to Germany to resume teaching at the College of Education in Kiel. But in January of 1940 he returned to Japan. Later he declared that upon the conclusion of the 1939 German-Soviet Treaty, which had caused German-Japanese relations to ice over suddenly, Ribbentrop had expressed interest in establishing ties to Japanese scholars and that he – Dürckheim – had offered to return to Japan to foster this.31 Again, this might be true, but it is not confirmed in the extant files of the Foreign Office or the Ministry of Education. At any rate, Dürckheim was given a research assignment in Japan once more (“a study of the foundations of Japanese thought and of strengthening friendly relations between Japanese scholars and Germany”) and, again, his stay was for a limited period of time only, until October 1942. This time his journey was funded by the Foreign Office, with such generosity that Dürckheim could afford a personal secretary, a spacious apartment, and a car.32

|

Figure 12. A delegation of the Hitler Youth in Japan, 1937: Dōmei kokusai shashin shinbun, 5 September 1938. |

Contrary to Victoria’s belief, however, Dürckheim continued to play only a secondary role rather than that of a “key figure” in German-Japanese relations.33 The German embassy in Tokyo was opposed to his visit to Japan, and, as before, he was not granted diplomatic status. Moreover, the post of cultural affairs officer, which had been vacant since the end of 1938, was not given to him but to Reinhold Schulze, an official of the Hitler Youth who had come to Japan in 1937 in order to strengthen the relations between German and Japanese youth organizations (see figure 12). Nevertheless, Dürckheim believed that his stay in Japan enabled him “to achieve what another individual would not have been able to accomplish in the same time.” He worked “day and night, to the limits of [his] power”, gave lectures, and wrote essays and booklets for Japanese publishing houses to present to the Japanese public “the true face of National Socialist Germany”, as he informed his former Kiel student Paul Karl Schmidt, whom he had brought into the Bureau Ribbentrop and who now headed the press and information department of the Foreign Office in Berlin.34 No studies have, as yet, been carried out on what Dürckheim published in Japanese media and on how the public in Japan reacted to these publications.

Dürckheim also propagated National Socialism tirelessly within Japan’s small German community. After 1945, a compatriot recalled how “everywhere and without interruption” he held lectures.35 But the response did not always appear to have met Dürckheim’s expectations. Another compatriot later described him as having been “a kind of classy propagandist with a high intellectual level who toured the country propagating National Socialism and the idea of a German empire” („Reichsidee”) and commented on how “awful” his public appearances were.36 Germans in Japan called him the “Rosenberg of the East”37.

After the end of the Pacific war, Dürckheim was one of very few Germans in Japan to be arrested by the US army and detained in Tokyo’s Sugamo prison. Although not formally indicted, he was kept there until February 1947, a few days before his forced return to Germany. Here the denazification court in 1948 classified him as having been a “fellow traveler” (Mitläufer) and sentenced him to a fine of 100 Reichsmark. This was a relatively light penalty in monetary terms; however, the conviction may have been heavy enough to prevent him from attaining a new professorship.

Consequently, in 1951, together with the widow of a former fellow student, Dürckheim founded “The Existential-Psychological Center for Learning and Encounter” („Existential-psychologische Bildungs- und Begegnungsstätte”), located in Rütte, a small village in the Black Forest of southern Germany. Here he embarked on a path of self redefinition. He became one of West Germany’s first Zen teachers and a prolific writer of books. Victoria mentions that Dürckheim never abandoned his view of kamikaze pilots as the embodiment of a perfect connection between the individual and the “whole” and as prime examples of selflessness.38 This, however, is only one example of how Dürckheim’s way of thinking had not changed since 1945. He simply adapted his language to postwar circumstances. What remained was his basic refusal of Western modernism – of technology, industrialization, urbanization, individualism, rationalism, mass society, and the loss of religious faith. And he continued to place greater importance upon the community than upon the individual. It seems never to have occurred to him that in Japan the praised ideal of selflessness had been subjected to the worst kind of political misuse, and that likewise in Germany the propagation of the individual’s selfless melting into an “ethnic community” („Volksgemeinschaft“), glorified as an example of “wholeness” or “oneness” („Ganzheit”), had helped create similarly disastrous results. Moreover, he never expressed interest in the question why Japan, despite its “cult of tranquility”39, had waged war against China and other South East Asian countries with exceptional brutality in order to become East Asia’s leading power, and why Western democracies, which had been looked down upon as being “individualistic” and “liberalistic”, had proven superior both to National Socialist Germany and authoritarian Japan. Like his neighbor Martin Heidegger, who lived near Rütte in the village of Todtnauberg, Dürckheim avoided examining the political, social and mentality-related causes of the war, let alone the question of personal responsibility and guilt. It is probably no coincidence that even his style of writing became similar to Heidegger’s in some respects.40

Some remarks about Eugen Herrigel

Victoria points out that Dürckheim, when he traveled to Japan, was familiar with an essay entitled “Zen or the Art of Archery” (Zen oder die Kunst des Bogenschießens), published in 1936 in two German periodicals which had only limited circulation.41 The author, Eugen Herrigel, had been a visiting professor in Sendai from 1924 to 1929 before accepting a professorship in philosophy at the University of Erlangen. He shared Dürckheim’s belief in National Socialism. Nonetheless, placing both men on the same level, as Victoria does, may not be completely justifiable. One reason is that Herrigel published far less than Dürckheim between 1933 and 1945 and his propagation of National Socialism was more restricted. Another might be that Herrigel is said to have made efforts to protect Jewish students who were still permitted to study under him after 1933. One should also note that, while serving as the university’s rector towards the end of the Second World War, he arranged for Erlangen to surrender to advancing American troops – an act that helped prevent a senseless, bloody battle for control of that town.42

German research into Herrigel’s writings and activities and to archived papers which contain information about Herrigel’s life after the end of the war reveal that Herrigel’s home was sequestered by US forces and occupied by families of American army officers, that most of his furniture, his collection of East Asian art, and his library disappeared, and the bulk of his manuscripts were burned in his garden. Furthermore, in December of 1945, Herrigel was deprived of his post as a professor and, in January of 1946, dismissed from the university entirely. Although he was reinstated as a full professor in June of 1948, he was sent into immediate retirement. As his house remained occupied, he moved to Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Upper Bavaria and republished his 1936 essay as a booklet, to which Daisetz Suzuki wrote the foreword.43

This booklet was an unexpected success. The second edition appeared as early as 1951, the fourth in 1954, the sixth in 1956. An English translation was published in New York. This success brought Herrigel “so many new and personally meaningful friendships” that he felt “abundantly compensated” for what he had lost 44 Suzuki, then still the best-known representative of Zen Buddhism worldwide, was among his visitors. Herrigel, “grateful” for his “good fortune”, proceeded to write another book, which dealt with the mysticism of Zen. Self-critical reflection on his earlier praise of National Socialism was as unknown to him as it was to Dürckheim.

Herrigel died in 1955, half forgotten in the field of German philosophy, in which he had never played a prominent role. Before his death, he burned the manuscript on the mysticism of Zen. Zen or the Art of Archery, however, became a real bestseller when, in the 1960s, interest in Zen Buddhism spread from the US to Europe. The 10th edition was printed in 1963, the 21st in 1982, the 43rd in 2003. In addition, the book has been translated into at least 13 languages, among them French, Spanish, and Swedish. In 1999, there even appeared an Estonian translation and, in 2005, one in Russian; some of these translations were also published in several editions.

Of the numerous publications on Japan that appeared in Germany between 1933 and 1945, Herrigel’s Zen or the Art of Archery remained the only one to gain popularity after the end of the Nazi regime. All other publications in question sank into obscurity, either immediately or in the course of two or three decades.45

Conclusion

The essays of Victoria and Baier shed light on little known relations between German National Socialism and Japanese Buddhism. Some aspects of their essays, however, may be supplemented and corrected. I have attempted to offer some relevant additional information here. It is also necessary to place the relations between German National Socialism and Japanese Buddhism in the larger context of the cultural relations between Germany and Japan between 1933 and 1945. For the Japanese part, a study of these relations remains a desideratum. In my view, Victoria’s narrow focus on Dürckheim and Suzuki and on the reference of the SS to the samurai has caused him to overestimate both dimensions. For the history of German National Socialism and German-Japanese relations between 1938 and 1945, Dürckheim’s activities were of marginal importance. Moreover, the reference of the SS to the samurai was at all times limited, if not undermined by Hitler’s insistence on the inferiority of Japanese culture and by a silent, sometimes even manifest, disdain of the “yellow race” by leading National Socialists.46 For Buddhism in both Japan and the West, however, the activities and views of individuals such as Dürckheim confirm what Victoria demonstrated in his book on Zen at War47: that – as with Christianity and other religions – even Buddhist concepts, like wholeness and selflessness, can be subjected to political misuse.

Hans-Joachim Bieber is professor emeritus of Modern History at the University of Kassel, Germany. His research focuses on German social history, including the history of German Jews; history of globalization; history of the ‘nuclear age’, and of German-Japanese cultural relations. His most recent book is SS und Samurai. Deutsch-japanische Kulturbeziehungen 1933-1945, München: iudicium 2014. His article on Cultural Relations between Germany and Japan in Nazi-Times. An Overview is forthcoming in Sven Saaler and Tobuo Najima (eds.): Mutual perceptions in Japanese-German relations: images, imaginings, and stereotypes.

Recommended citation: Hans-Joachim Bieber, “Zen and War: A Commentary on Brian Victoria and Karl Baier’s Analysis of Daisetz Suzuki and Count Dürckheim”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 20, No. 2, May 19, 2015.

Related articles

•Brian Victoria, Sawaki Kōdō, Zen and Wartime Japan: Final Pieces of the Puzzle

• Narusawa Muneo and Brian Victoria, “War is a Crime”: Takenaka Shōgen and Buddhist Resistance in the Asia-Pacific War and Today

• Karl Baier, The Formation and Principles of Count Dürckheim’s Nazi Worldview and his interpretation of Japanese Spirit and Zen

• Brian Victoria, Zen Masters on the Battlefield (Part I)

• Brian Victoria, Zen Masters on the Battlefield (Part II)

• Brian Victoria, A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan Count Dürckheim and his Sources—D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel

• Vladimir Tikhonov, South Korea’s Christian Military Chaplaincy in the Korean War – religion as ideology?

• Brian Victoria, Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima

• Brian Victoria, Karma, War and Inequality in Twentieth Century Japan

Notes

1 Brian Daizen Victoria: D.T. Suzuki, Zen and the Nazis, in: The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 11, Issue 42, No. 4 (October 28, 2013); Karl Baier: The Formation and Principles of Count Dürckheim’s Nazi Worldview and his Interpretation of Japanese Spirit and Zen, ibid., Vol. 11, Issue 48, No. 3 (December 2, 2013); Brian Daizen Victoria: A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan: Count Dürckheim and his Sources – D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel, ibid., Vol. 12, Issue 3, No. 2 (January 20, 2014).

2 Hans-Joachim Bieber: SS und Samurai. Deutsch-Japanische Kulturbeziehungen 1933-1945, Munich: iudicium 2014. In the following I will refer to this book only; exact information on my sources can be found on the indicated pages.

3 Cf. Victoria 2013, p. 2 ff.

4 Quoted ibid.

5 Quoted ibid.

6 Taisetzu Suzuki: Entstehung und Entwicklung des japanischen Buddhismus, in: Ostasien-Jahrbuch 10 (1931), pp. 54-61; Daisetsu Teitarō Suzuki: Japanische Kultur und Zen, in: Nippon, vol. 1935, p. 74-78.

7 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 188 f. and 272.

8 Hans F.K. Günther: Die Nordische Rasse bei den Indogermanen Asiens, Munich 1934, p. 52 and 57.

9 Jakob Wilhelm Hauer: Das religiöse Artbild der Indogermanen und die Grundtypen der indo-arischen Religion, Stuttgart 1937, p. 239 f. and 269 ff.

10 Werner Bichler: Japanisches Heldentum, in: Die Junge Front 7 (1936), p. 357, with reference to Erwin Bälz: Über die Todesverachtung der Japaner, ed. by Toku Bälz, Stuttgart 1936; cf. Bieber 2014, p. 395 ff. – Reinhard Höhn, responsible for cultural affairs [Kulturreferent] in the SS Security Service (SD), dedicated a collection of Buddhism lectures to his superior, Heinrich Himmler, for Christmas in 1935, saying that they were “an expression of Aryan thinking“ and a part of “the dictates of our order (Weistum unseres Ordens)“. (Höhn to Himmler, Dec. 31, 1935, quoted in Helmut Heiber: Walter Frank und sein Reichsinstitut für die Geschichte des neuen Deutschlands, Stuttgart 1966, p. 887 f.). Indeed, among religious writings, the lectures of Buddha were said to have been the ones that Himmler most esteemed. (cf. Felix Kersten: Totenkopf und Treue, Hamburg 1953, p. 185).

11 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 640 ff. und 810 ff.

12 Die Samurai. Eine alte Kampfgemeinschaft erneuert den Staat, in: Das Schwarze Korps, March 5, 1936, p. 12, and March 12, p. 12.

13 Heinz Corazza: Japans Wunder des Schwertes, Berlin: Klinkhardt & Biermann 1935.

14 Victoria 2014, p. 16.

15 Peter Longerich: Heinrich Himmler, Munich 2008, p. 291.

16 Ibid.

17 Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki: Die große Befreiung. Einführung in den Zen-Buddhismus. Geleitwort von C. G. Jung, Leipzig: Curt Weller & Co. 1939; Zen und die Kultur Japans, Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1941.

18 „Zen und der Samurai”, in: Völkischer Beobachter, South German edition, January 11, 1942. Victoria does not know that the Völkische Beobachter was published in different editions and ascribes the quotation from Suzuki’s book wrongly to the main edition which appeared in Berlin; cf. Victoria 2014, p. 15.

19 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 948 ff.

20 Albrecht Fürst von Urach: Das Geheimnis japanischer Kraft, Berlin: Eher 1942. The author had been correspondent of the Völkischer Beobachter in Tokyo between 1934 and 1938.

21 Cf. Victoria 2014, p. 19.

22 Security Service report, Aug. 6, 1942, in: Heinz Boberach (ed.): Meldungen aus dem Reich 1938–1945, Herrsching 1984, vol. 11, pp. 4042-4044..

23 Himmler on June 21, 1944; in: Heinrich Himmler: Geheimreden 1933-1945 und andere Ansprachen, ed. by Bradley F. Smith, Frankfurt 1974, p. 193.

24 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 1005.

25 Cf. Dürckheim’s self-portrayal in: Ludwig J. Pongratz (ed.): Psychologie in Selbstdarstellungen, Bern: Huber 1973, p. 159, and Karlfried Graf Dürckheim: Der Weg ist das Ziel, Göttingen 1992, p. 41.

26 Edith and Rolf Zundel: Leitfiguren der Psychotherapie, Munich1987, p. 162.

27 For the following paragraph cf. Bieber 2014, p. 604 ff., with an exact indication of sources.

28 Cf. Victoria 2014, p. 6 f.

29 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 656.

30 Cf. ibid., p. 509 ff.

31 Cf. Dürckheim 1992, p. 40, and Victoria 2014, p. 6.

32 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 738 ff. – The fact that Dürckheim travelled to Japan this time via the Transsiberian Railway cannot be explained by the 1939 Pact between Hitler and Stalin, as Victoria 2014, p. 5, assumes. Since its opening in 1916 the Trans-Siberian Railway had offered an alternative to sea travel to Japan. Moreover, after the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, it was the only connection between Europe and Japan that remained open to Germans. German shipping lines closed down their routes to East Asia; and sailing on vessels belonging to non-German lines proved dangerous for Germans, as British war ships often stopped and inspected these vessels at sea to arrest German passengers if any were found.

33 Cf. Victoria 2014, p. 6.

34 Dürckheim to Schmidt, November 11, 1940; quoted by Bieber 2014, p. 740; the middle part of the quotation is taken from a letter written by Dürckheim quoted in Gerhard Wehr: Karlfried Graf Dürckheim. Leben im Zeichen der Wandlung, Freiburg: Herder 1996, p. 115.

35 Bernd Eversmeyer in Franziska Ehmcke / Peter Pantzer (eds.): Gelebte Zeitgeschichte. Alltag von Deutschen in Japan 1923-47, München: iudicium 2000, p. 15.

36 Dietrich Seckel ibid. p. 51. For more details of Dürckheim‘s lectures and publications in Japan cf. Bieber 2014, p. 738 ff., 821 ff., 935 ff., and 1026 ff. – One of Dürckheim‘s lectures was published by the OAG in 1943 (Graf K. von Dürckheim-Monmartin: Erkenntnis und Werk als Ausdruck des europäischen Geistes, in: Nachrichten der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens, Tokyo (NOAG) 63, March 1943, pp. 13-33).

37 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 1094. – Alfred Rosenberg was the leading ideologist of National Socialism and editor of the party organ Völkischer Beobachter.

38 Cf. Victoria 2014, p. 20, and Karlfried Graf Dürckheim: Mein Weg zur Mitte, Freiburg 1991, p. 122.

39 Cf. Karlfried Graf von Durckheim: The Japanese Cult of Tranquillity, London: Rider & Co. 1960.

40 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 1150 ff.

41 Eugen Herrigel: Zen in der Kunst des Bogenschießens, in: Ostasiatische Rundschau 17 (1936), pp. 355-357 and 377-381, and Nippon, vol. 1936, pp. 193-212.

42 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 275 and 1055.

43 Cf. ibid. p. 1084 and 1108.

44 Herrigel to Gundert, Sept. 26, 1950; quoted ibid. p. 1117.

45 Cf. Bieber 2014, p. 1139 ff.

46 In Mein Kampf Hitler stated that the Japanese were merely “bearers of culture” (kulturtragend) in contrast to the Aryans, whom he saw as being “culture creating” (kulturschöpferisch). Hitler however did have some respect for Japan’s military and was impressed that the country had remained untouched by “international Jewry” (das internationale Judentum). See Bieber 2014, p. 153 ff.; for racial disdain of the Japanese during the war ibid. p. 767 f., 781 fn. 99, and 862.

47 Brian Victoria: Zen at War, New York: Weatherhill 1997.