This article highlights Japan’s National Resilience (“Kokudo Kyoujinka”) strategy, a very important, multi-trillion-yen initiative that was (incredibly) ignored during the campaign preceding the December 14 election and continues to be. Like most countries’ efforts to bolster resilience against accelerating climate change and other patent threats, the content of Japan’s plan is a work in progress. But the scale and scope of Japan’s strategy is unparalleled, as it is slated to grow from YEN 3.6 trillion in FY 2014 to YEN 4.54 trillion in FY 2015.1 Properly done, it could be of immense benefit to Japan’s resilience and sustainable growth prospects as well as to the global community. However, in the absence of any clear direction to Abenomics, Japan’s initiative could be largely squandered on roads and other concrete-intensive projects. Moreover, the programme’s core agencies, especially the newly established Association for Resilience Japan, could be conscripted in Japan’s revisionists’ fight for constitutional reform and the attack on pacificism and critical thinking in civil society.

This article first examines the election results and interpretations of them, to show the troubling post-election uncertainty of Japanese politics. It then considers the resilience initiative in light of that uncertainty. The concluding section offers some suggestions on how to help foster a truly resilient Japan and prevent it from squandering the opportunity, instead becoming a source of even more political and economic instability in East Asia.

The “Abenomics” Election and its Rashomon Mandate

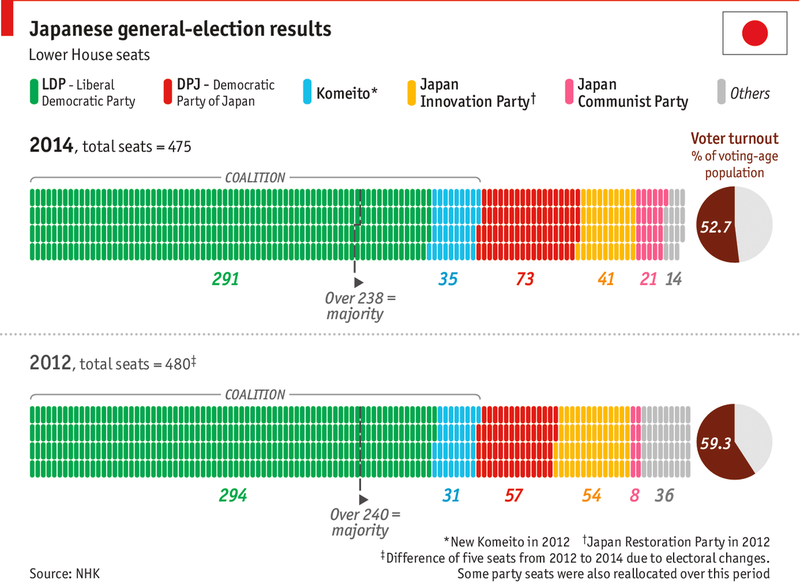

As we see in the accompanying figure on “Japanese general-election results” borrowed from The Economist, Japan’s national elections to the Diet’s lower house saw PM Abe Shinzo’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) lose 4 seats, going from 295 to 291, even as turnout dropped to a postwar low of 52.7%. The LDP’s coalition partner Komeito, at least rhetorically committed to pacifism, gained 4 seats to stand at 35 representatives. Hence, as in the general election almost precisely two years ago, on December 4, 2012, the LDP easily cleared the majority line of 238 seats (in a 475 seat chamber). And together with Komeito, the LDP retained the two-thirds majority needed to override the upper house as well as control all committee chairs and appoint a majority of committee members in each.

The opposition generally did not do well, in spite of collaborating by strategically fielding candidates in many single-seat constituencies.2 The largest opposition party, the centrist Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), increased its seats from 62 to 73. But it was clearly not running to win, and its hapless leader Kaieda Banri lost his own seat and resigned his leadership position. The centre-right Japan Innovation Party, co-chaired by maverick Osaka Mayor Hashimoto Toru, barely managed to hold its pre-election position of 42 seats, taking 41 seats by heavy reliance on the proportional representation vote (180 seats are allocated in 11 regional blocs by this second ballot). At the same time, vocally nationalist octogenarian Shintaro Ishihara’s “Party for Future Generations” dropped from 20 seats to 2. The left-wing Japan Communist Party (largely social-democratic in its leanings) provided one big surprise, rocketing from 8 seats to 21.

One of the most succinct and persuasive post-election interpretations of the LDP’s win was delivered by the Asahi Shimbun on December 18. They reported that their in-house opinion poll conducted over December 15 to 16 found that only 11% of respondents believed the LDP took over 290 seats because of Abe’s policies. Fully 72% saw the election results as due to the lack of an attractive opposition party. Moreover, only 31% expressed positive expectations concerning Abe’s upcoming policy choices, whereas 52% expressed considerable anxiety about what Abe might do.3 And one can certainly understand the concern, as on the eve of his win Abe stressed that he saw it as a mandate for constitutional reform.4

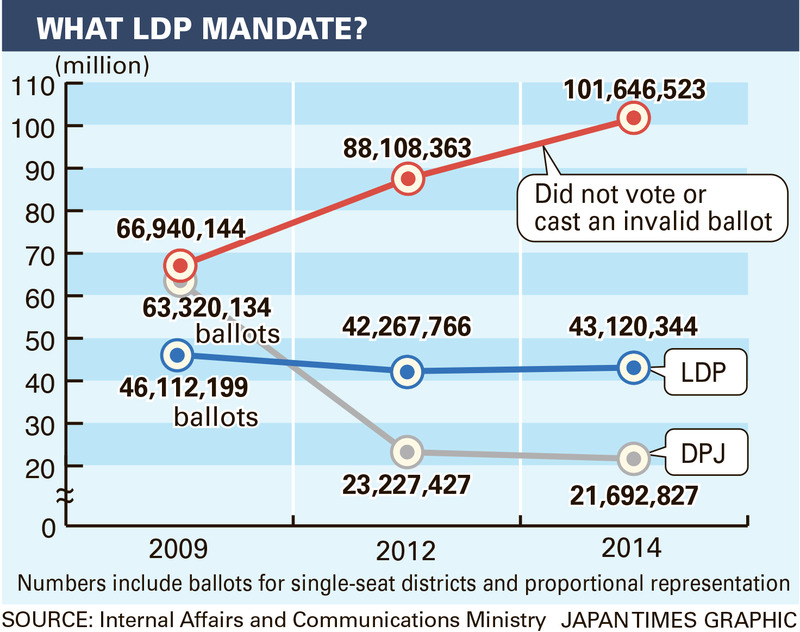

That anxiety about Abe and popular support for the pacifism associated with Article 9 of the Constitution, together with the lack of a large and credible opposition party through which to express these concerns, appears to have led to gains for Komeito and the Communist Party5 as well as a massive increase in abstentions. The figure titled “What LDP Mandate?” from a December 17 Japan Times analysis,6 shows – via the blue line – that due to the collapse in turnout the LDP actually got fewer votes in 2014 than when it was crushed by the DPJ in the 2009 election. The red line represents the number of adult Japanese who either did not vote or spoiled their ballot (the latter number being 3.2 million). The Japan Times, The Asahi Shimbun, and even The Economist7 rightly ask whether there was indeed a renewed mandate for Abenomics itself as well as constitutional reform. Nevertheless, the LDP victory assures it of four more years of rule.

Yet most business-oriented assessments appear focused on economic and financial implications. Thus post-election analyses assured the investor class that Abenomics is likely to see smooth sailing with “consumption and investment…relatively untethered” thanks to fiscal and financial stimulus.8 Underscoring this argument was the claim that the electoral win was also a victory over the Ministry of Finance and its capacity to emphasize fiscal austerity (e.g., consumption tax increases).9 These analyses reflect an apparent hope that the Abe regime will aim at assuring a sustainable economic recovery, helping to bolster a global economy that may be in deep trouble. Many investors and their journalistic commentators seem to need to believe that Abe is a rational actor who will keep his nose to the grindstone of structural reforms they favor.

Other observers are rather less sanguine, like the majority of the Japanese public in the Asahi poll. Quoted in the Associated Press, James Schoff, Japan expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and former adviser on East Asia policy at the U.S. Defense Department, cautioned that Abe might “get distracted” by constitutional revision and other pet issues. Schoff warned that “If he [Abe] spends his political capital on those issues instead of on these other things that the United States is prioritizing, maybe we wouldn’t be as excited about that.”10

The upshot is that what was decided by Japan’s election result is a highly contested matter. There was little clarity about why the election itself was necessary, and limited engagement with the critical issues facing Japan: environmental, energy, fiscal, financial, security and other challenges confronting Japan. That vagueness leaves much room for mischief on revisionism and little latitude for effective opposition to legislation, save for pressure from the ranks of Komeito. It also risks dissipating the immense potential for resilience, to which this article next turns.

Japan’s National Resilience Plan

Japan’s National Resilience plan emerged from the LDP while it was still in opposition. In spring of 2012, news reports revealed LDP plans for spending YEN 200 trillion over 10 years to bolster the country’s infrastructure in the face of disaster threats (especially earthquakes) as well as the rising costs of maintenance in the context of a shrinking population and weakening economy. The LDP’s Nikai Toshihiro, a prominent transportation policymaker and chair of the LDP ”National Resilience Comprehensive Study Commission,” first mooted the idea in the Diet in April of 2012. The plan was then adopted by the party on June 1 of the same year, and submitted to the Diet on June 4 as the “National Resilience Basic Bill.” The LDP also incorporated the National Resilience plan in its campaign platform for the December 4, 2012 election.

|

National Resilience Promotion Headquarters: Japanese Cabinet |

After a round of deriding the programme as pork-barrel spending last spring, the opposition parties and the media paid scant attention to it11 Interest in the leading business newspaper, the Nikkei Shimbun, tapered off for example. Then on June 30 the Nikkei Shimbun ran a multi-article, laudatory special on National Resilience, in tandem with the July 1 establishment of the Japan Association for Resilience.12

However, in the wake of that special report and up to the present, the Nikkei ran only one article mentioning the YEN 4.5 trillion National Resilience programme and its budget. The article is an August 31 “Economics Lecture” (“keizai kyoushitsu”) discussion by Doi Takero (a professor of public finance at Keio University). Doi advises that the then-upcoming Abe cabinet reshuffle be used to get a grip on the nominal commitment to “National Resilience” that – to him – appeared likely to be used as pork-barrel spending to attract votes in the nationwide local elections of 2015 (slated for April).

On November 30, just before the December 2 start of the recent election campaign, the Genron NPO (a think tank committed to open democracy) warned of pork-barrel aspects in the current draft of the National Resilience programme. It was especially concerned about the possibly very expensive commitments to linear shinkansen and New Tomei road projects that are penciled in. It also criticized Abe and his cabinet’s failure even to talk about the programme in the Diet. At the same time, Genron NPO showed that it understood the need for resilience.13

Aside from the periodic perusals and the several indications of concern over potential waste, there has been scant deliberation over the programme. Whether FY 2014’s resilience budget is being spent productively obviously depends on how one measures various disaster risks as well as a thorough analysis of the spending categories. It would appear that such analyses have not yet been done, or at least published.

As noted, the current programme for FY 2015 remains a work in progress. But it clearly contains some very promising initiatives, many of which were not in the last year’s plan. These elements include the use of engineered wood (cross-laminated timber) in building construction, the use of natural barriers (as opposed to concrete) for disaster resilience, sophisticated means of weather tracking and warning, distributed power and its infrastructure, and a wide variety of similar resilience-enhancing measures. The resilience programme is also becoming enmeshed with Japan’s smart community programmes, often with the same figures (such as Kashiwagi Takao) playing central roles in both.14

And this year’s overall plan is also potentially more effective because it is being combined with the evolving role of the above-noted Japan Association for Resilience as well as local plans. This approach could open up programme design and implementation to a broader range of actors, increasing the potential for more creative input as well as oversight. Alternatively, these same mechanisms could serve to enhance the coordination capacities of nationalist, centralizing elites, especially in an economic, energy or other type of grave crisis.

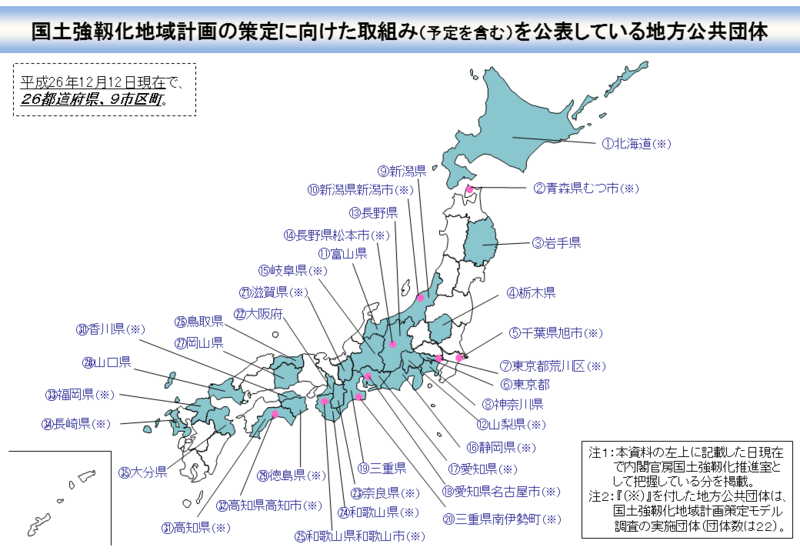

As of December 12, 2014, fully 26 prefectures and 9 cities in every region of Japan have their own resilience programmes on-line, as shown in the attached map (in Japanese). The content of these local programmes is still being worked out. Their number is likely to increase rapidly over the coming weeks, with increasing clarity in their details.

Conclusions

As noted earlier, the election campaign itself, as well as post-election debate, neglects the fact that Japan has embarked on a well-funded and well-organized National Resilience programme. The programme deserves critical analysis because of its scale and because, depending on final determinations of spending priorities, its scope now includes measures to accelerate the diffusion and sophistication of climate-resilientsmart communities. At the same time, because of revisionist priorities, the plan may become largely a pipeline for pork-barrel spending to buy off local support and deepen the grip of revisionist politics. So getting more attention paid, right now, to Japan’s evolving National Resilience programme seems very important.

Surely another major reason to pay attention is to maximize the positive demonstration effect for other countries. YEN 4.5 trillion is a lot of money, even at a time when Abenomics has cut the USD-YEN exchange rate to about YEN120/USD. To calculate the truly resilient portion of this spending requires tracking the national and local programmes and then adding their constructive spending to Japan’s already significant investment in individual smart communities, the diffusion of distributed generation and infrastructure in other budgets, and the spending of local governments themselves (such as on resilient waterworks). This is a tall order, given the opacity of the overall programme’s spending on individual items and the lack of detailed critical analysis from the Japanese media. But getting more information on the scale of what Japan is doing may help encourage smart investment overseas, where fiscal austerity hinders spending as well as lack of vision on resilience.

In the US, for example, President Barack Obama’s February 14, 2014 proposal for a USD 1 billion “Climate Resilience Fund” was seen as likely to “face tough questions in Congress” in spite of patent need.15 Not only is this a small fraction of the Japanese program already underway, but a notable fact is that the United States has only one specialist on storm surges, for the entire country. Yet, as Americans saw themselves during Hurricane Sandy, which caused 72 direct deaths and over USD 50 billion in damage,16 storm surges are becoming more frequent and intense. When the conditions are right, they are almost indistinguishable from tsunami, as is strikingly evident in this short video clip from Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) that hit the Philippines in early November of 2013 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XUZFW54vtDo.17

Moreover, the US weather services are severely impaired because the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)18 is in the Department of Commerce and has suffered considerable fiscal restraint. NOAA is apparently unable to fill numerous staff positions and get new equipment. The agency was not even able to conduct national forecasts on Hurricane Sandy once it became a hybridstorm because regulations do not permit it and the specialists were also worried they would overtax their limited software.19

Perhaps the United States is an outlier in this lamentable lack of preparedness, but it appears to share the situation of many others. In any event, it seems very much in the collective interest of the United States and other nations to follow what Japan is doing on resilience, encouraging smart investment as much as possible while also learning from it. And the more smart investment Japan carries out in the face of real threats, the more likely it is to contribute to regional stability rather than detract from it.

Andrew DeWit is Professor in Rikkyo University’s School of Policy Studies and an edtor of The Asia-Pacific Journal. His recent publications include “Climate Change and the Military Role in Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response,” in Paul Bacon and Christopher Hobson (eds) Human Security and Japan’s Triple Disaster (Routledge, 2014), “Japan’s renewable power prospects,” in Jeff Kingston (ed) Critical Issues in Contemporary Japan (Routledge 2013), and (with Kaneko Masaru and Iida Tetsunari) “Fukushima and the Political Economy of Power Policy in Japan” in Jeff Kingston (ed) Natural Disaster and Nuclear Crisis in Japan: Response and Recovery after Japan’s 3/11 (Routledge, 2012). He is lead researcher for a five-year (2010-2015) Japanese-Government funded project on the political economy of the Feed-in Tariff.

Recommended Citation: Andrew DeWit, “Japan’s “National Resilience Plan”: Its Promise and Perils in the Wake of the Election”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 51, No. 1, December 22, 2014.

Related articles

• Andrew DeWit, Japan’s Resilient, Decarbonizing and Democratic Smart Communities

• Andrew DeWit, Japan’s Radical Energy Technocrats: Structural Reform Through Smart Communities, the Feed-in Tariff and Japanese-Style “Stadtwerke”

• John Mathews and Hao Tan, China’s renewable energy revolution: what is driving it?

• Andrew DeWit, A New Japanese Miracle? Its Hamstrung Feed-in Tariff Actually Works

• Andrew DeWit, Japan’s Rollout of Smart Cities: What Role for the Citizens?

• Andrew DeWit, Distributed Power and Incentives in Post-Fukushima Japan

• Sun-Jin YUN, Myung-Rae Cho and David von Hippel, The Current Status of Green Growth in Korea: Energy and Urban Security

Notes

1 The latter number is the requested total as of August 2014. See p. 4 of (in Japanese) “2015 National Resilience-Related Budget Request Outline,” Japan Cabinet National Resilience Promotion Office, August 2014.

2 On this, see “Unified opposition party eyed to challenge LDP,” The Japan News, December 16, 2014.

3 See (in Japanese) “72% Declare the Reason for the LDP’s Massive Win to be ‘Lack of an Attractive Opposition,” Asahi Shimbun Poll,” Asahi Shimbun, December 18, 2014.

4 See (in Japanese) “Upper House Election: Abe declares ‘I want to press for constitutional reform’,” Mainichi Shimbun, December 15, 2014.

5 As Daniel Sneider, associate director for research of Stanford University’s Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (APARC), argues: “Many people who wanted to file a protest vote against Abe chose the JCP because they did not see the DPJ or others clearly differentiating themselves from the LDP,” in Peter Ennis, “Sneider: This election was all about power,” Dispatch Japan, December 18, 2014.

6 See Reiji Yoshida, “Low voter turnout mars Abe’s claim of election triumph,” Japan Times, December 17, 2014.

7 See “Japan’s snap election result: Romping home,” The Economist, December 15, 2014.

8 See Anthony Rowley, “In Japan Election, Abe Victory Not Quite a Referendum on Abenomics,” Institutional Investor, December 17, 2014.

9 On this argument, see Masaaki Iwamoto, Toru Fujioka and Kyoko Shimodoi, “Japan Fiscal Fundamentalists Face Weakened Sway With Abe Win,” Bloomberg, December 17, 2014.

10 Mari Yamaguchi and Ken Moritsugi, “Big win could help Abe pursue nationalist goals,” Japan Today, December 15, 2014.

11 For example, the title of one article (in Japanese) by Mori Seiyu is itself telling: “The False Façade of the LDP National Resilience Bill,” JB Press, March 13, 2013.

12 The Association is in the midst of producing plans for a variety of different programme areas. Its website is here.

13 See (in Japanese) “Assessing 2 Years of the Abe Government’s Recovery and Disaster-Reduction,” Genron NPO, November 30, 2014.

14 Kashiwagi is a member of the Japan Association for Resilience and is also a central figure in Japan’s smart communities. On the latter, see Andrew DeWit, “Japan’s Radical Energy Technocrats: Structural Reform Through Smart Communities, the Feed-in Tariff and Japanese-Style ‘Stadtwerke'”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 47, No. 2, December 1, 2014.

15 David Malakoff, “Obama to Propose $1 Billion Climate Resilience Fund,” Science, February 14, 2014.

16 See “Hurricane/Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy, October 22–29, 2012 (Service Assessment),” United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service, May 2013.

17 See “WATCH: Tsunami-like power of Yolanda’s storm surge,” ABS-CBN News, November 17, 2013.

18 See NOAA’s website.

19 On these items, see the Ecoshock Radio December 17, 2014 interview with Kathy Miles, author of “Superstorm: Nine Days Inside Hurricane Sandy”.