Introduction

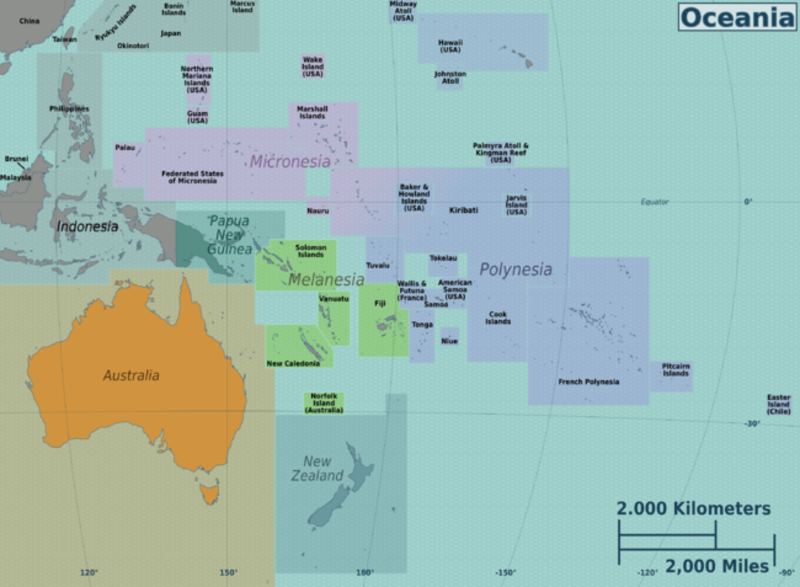

Asia and the Pacific—these two geographic, political and cultural regions encompass entire life-worlds, cosmologies and cultures. Yet Indonesia’s recent enthusiastic outreach to Melanesia indicates an attempt to bridge both the constructed and actual distinctions between them. While the label ‘Asia-Pacific’ may accurately capture Indonesia’s aspirational sphere of influence, it is simultaneously one that many Pacific scholars have resisted, fearing that the cultures and interests of the Pacific are threatened by the hyphen1. This fear is justified, we contend, as Indonesia progressively puts itself forward in Pacific political forums as the official representative of ‘its’ Melanesian populations2—a considerable number of whom support independence from the Indonesian state3.

In this article, we examine why Indonesia is increasingly representing itself as a Pacific ‘nesia’ (Greek for islands), seemingly to neutralise West Papua’s claim to political Melanesianhood. Then we analyse the ways Indonesia is insinuating itself into Melanesian politics and its attempts to undercut Melanesian support for West Papuan self-determination. Finally we consider the implications of Indonesia’s lengthening arm into Melanesian politics for Melanesia’s regional political bloc, the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), and for West Papuan politics. International support for West Papuan independence is critical to the movement’s traction, as it was in the cases of East Timor and South Sudan4. As West Papua refutes Indonesia’s claim that the conflict is an internal domestic one, and enlists the support of fellow Melanesian nations to help internationalise its concerns, Indonesia is forced to respond on the international stage too, seeking first to woo West Papua’s strongest potential allies, the MSG members. We conclude by arguing that if the MSG and individual Melanesian states want to respond to Indonesia by including it in their political and trade networks, it is their prerogative to do so. However, they should beware of further stifling already marginalised Melanesian voices such as those of West Papuans, this being the principal deleterious effect of Indonesia’s recent foray into Melanesian politics.

|

Map showing Indonesia in relation to Melanesia. Image credit |

Indonesia’s Pacific Pitch

West Papua’s geopolitical liminality in relation to Asia and the Pacific Islands positions it as the ‘hyphen’ in the pan-regional Asia-Pacific construction5. Culturally it is of the Pacific, with a Pacific identity, which, on account of its geographic location and colonial history, has had its interests subordinated to its much larger Asian occupier, Indonesia. Over the last five years however, West Papuan voices for self-determination have increasingly made their way into the consciousness of the regional and the international community6. In response, over the past two years in particular, Indonesian diplomacy has vigorously extended itself east into Melanesia in an attempt to maintain control over West Papua, its territorial bridge to the Pacific7. But Indonesia is not only using West Papua to attain status as a member of the Pacific regional community, it is also seeking Pacific status to legitimise its stranglehold on West Papua8.

Indonesia has had a long relationship with the Pacific, and a largely violent one with what is now West Papua. In Asia in the Pacific Islands, Ron Crocombe describes Indonesia’s historical links with the Pacific as being forged through a series of waves. The first wave produced the ancestors of most Pacific Islanders who came originally from Taiwan and travelled via Indonesia to reach Melanesia9, and later, Polynesia and Micronesia10. However, Crocombe downplays the significance of these migration waves to Asia and Pacific Islands relations, claiming that these early populations had very little interaction with Asia after their exodus11. West Papuans living in the westernmost part of the island of New Guinea and its outlying islands were not so fortunate. From the 15th century, the sultans from the Indonesian islands of Tidore and Ternate conducted violent slave raids into West Papua, plundered exotic goods and extracted tribute12. The second wave of Asians to the Pacific Islands, according to Crocombe, stretched from 1800 to 1945 and mainly included workers hired to labour in European colonial settlements. Following this pattern, the Dutch colonisers of West Papua used Malukan colonial subjects as teachers and administrators in West Papua, much to the resentment of West Papuans13.

The third wave was the most violent of all for West Papuans. While the Dutch had prepared an elite group of West Papuans for independence by 1961, the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia insisted that West Papua join it. In 1962, against a backdrop of Cold War geopolitics, the United States (US) and Australia backed Indonesia’s claim to West Papua and negotiated a transfer of the territory to Indonesia, without consulting the local population. In 1969, the UN cursorily oversaw and endorsed the so-called Act of Free Choice, a referendum in which less than one per cent of the West Papuan population was required, by force, to vote for integration with Indonesia on behalf of the entire territory. Since 1964, West Papuans have conducted military and peaceful campaigns for independence, while demographers estimate that between 100,000 and 500,000 West Papuans have been killed under the Indonesian occupation14. Crimes against humanity committed by Indonesian security forces, documented extensively elsewhere15, have been horrific and frequent, yet ignored. Indeed, serious accusations of genocide have been mounted against Indonesia for its actions and intentions in West Papua16.

Despite its forced incorporation of West Papuans and several other Melanesian populations within its state boundaries, through which it claims a place at the Melanesian political table, Indonesia is not part of Melanesia17. While some anthropologists highlight the contiguity of Asia and Melanesia, and the blurring of ethnicities and cultures in the transitional region between New Guinea and Asia18, in terms of chosen identity19, invented tradition20 and sociocultural practices21, West Papuans have much more in common with the rest of Melanesia than with Asia22. And while identities are neither primordial nor unchanging but are worked out in relation to otherness23, and all categorisations of humans are social constructs, the living out of constructed identities is experienced as reality. Regional identity may not be as salient to many Pacific Islanders as language and place, but it is important to those elites whose job it is to define the nation-state and its place in the international system24. Thus, as Selwyn Garu, member of the Vanuatu Council of Chiefs stated in 2009, “Melanesia is not a concept, it’s a reality”25. Such statements “say…something”, according to Stephanie Lawson, “not just about the social construction of reality but about the reality that social constructions come to acquire in the world of politics”26. They also say something about why, despite some overlap of ethnicities and cultures in what Indonesia considers to be the far eastern limit of its state, West Papuans are “ontologically attached”27 to the Melanesian Pacific, as a distinct and separate region from Indonesia’s Asia.

However, Indonesia has much to lose28 if West Papua is included politically, in addition to its current cultural affiliations, with the Pacific. It is not possible for Indonesia to deny West Papuans’ cultural Melanesian-ness, an identity label that has gained wide support among West Papuans, Papua New Guineans, Ni-Vanuatu, Solomon Islanders and Kanaks in the post-PNG and Vanuatu independence era29. The label ‘Melanesia’—‘mel’ (from the Greek ‘melas’, meaning ‘black’) and ‘nesia’ (from ‘nesos’, meaning ‘islands’)—formalised in 1832 by French explorer Dumont D’Urville as the name of the south-west Pacific region in 1832—has largely shed its racial and racist connotations30. Being generally darker in skin colour and more egalitarian31 in social organisation than other lighter-skinned and hierarchically-structured societies in the Pacific encountered by early colonial explorers, Melanesia was a pejorative32 and racial label, in contrast to the geographically labelled Pacific regions of Polynesia (many islands) and Micronesia (small islands). Despite the label’s objectionable genealogy, indigenous intellectuals from the 1970s onward have reclaimed Melanesian-ness as an anticolonial33 and panethnic34 identity based largely on various discourses—the Melanesian Way35, wantokism36 and kastom37, which largely exclude Western, Asian and even Polynesian values38 on the basis of either their foreignness and (or) their imperialist connotations.

In order to deny West Papuan representation at Melanesian and Pacific forums, Indonesia is trying to identify itself as a Pacific (Melanesian) as well as an Asian state. Indonesia has previously represented itself as “Father of the Nesias”39, referring to the path the Papuan and Austronesian peoples historically followed through Indonesia to the other ‘nesias’—Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia. But being ‘Nesian’, as Kirsten McGavin points out, is a Pacific Islander notion. As an identity it is not necessarily ethnically defined, and it can incorporate many Islander cultural practices, particularly when groups of ‘Islanders’ from different Pacific countries gather socially in an ‘outside’ country. Thus, the hula might be performed at an Australian wedding uniting a New Zealander and Papua New Guinean, even though the hula is a Hawaiian dance, precisely because the celebration is taking place in a panethnic Pacific Islander community40. Identifying as ‘Nesian’, therefore, is problematic for Indonesia because as a panethnicity, being ‘Nesian’ is “based on [a Pacific Islander] cultural background and similarity of experiences41.” The experiences of Pacific Islander West Papuans at the hands of the Indonesian state have been incomparably more tragic42 than those of most other peoples grouped together as Indonesians.

Secondly, Indonesia encounters problems with its ‘Nesian’-ness in its status as a state, rather than a region. Being regions, Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia provide a framework within which their individual states can work together relatively amicably through regional and bilateral relationships. Indonesia, as a nation-state, cannot allow the many nations it encompasses to freely associate as sovereign political entities. Thus Indonesia lacks the democratic functioning of the three Pacific ‘Nesias’ of which it claims parentage (by virtue of the use of its land by Melanesia’s, Polynesia’s and Micronesia’s original inhabitants while in transit from Taiwan to their Pacific destinations). Regardless of these deficiencies in Indonesia’s claims to Melanesian representativeness, however, realpolitik negotiations saw Indonesia granted observer status in 2011 at the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG)—Melanesia’s subregional political and trade bloc. This transpired despite the MSG being founded in 1986 to strengthen Melanesian solidarity and promote Melanesian interests, including the decolonisation of Kanaky43. The MSG includes Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, Fiji and the Kanak Socialist Front for National Liberation (FLNKS)44, but has not yet welcomed West Papua into its fold.

The West Papua National Coalition for Liberation (WPNCL), which represents many West Papuan independence groups at the international level, has been working to highlight the dubiousness of Indonesia’s claim to Melanesian representativeness, and for several years lobbied the MSG for observer status for itself with little effect. This changed at an MSG meeting in New Caledonia in 2013, when the WPNCL prepared yet another application for observer status. The evening before it was due to be submitted the WPNCL leaders attending a special pre-summit reception were encouraged by the Chair of the FLNKS to apply for full membership45: the application form was quickly adjusted accordingly. Although it is not within the MSG’s remit to formally intervene in the Indonesia-West Papua conflict, West Papuans hope that if they are admitted to the MSG, that bloc will have sufficient clout to take their case forward to the UN Decolonisation Committee. West Papuans found encouragement for this move in a casual remark by UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon at the 2011 Pacific Islands Forum in New Zealand46.

The MSG decided during its June 2013 summit, at the insistence of Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands, to endorse West Papua’s right to self-determination, and stated that the atrocities of the past five decades in West Papua needed to be taken up with the Indonesian government. But they held off from a decision on West Papuan membership, instead accepting Indonesia’s invitation to host a Foreign Ministerial Mission (FMM) of MSG leaders to Jakarta and West Papua, headed up by Fiji, so that MSG leaders could witness first-hand conditions in West Papua47. The WPNCL would be advised, it was decided, of the MSG’s decision within six months of the FMM visit. Despite the delay of the final decision on full membership, West Papua’s reception at this MSG summit was a small victory in itself: for the first time West Papuan representatives were given observer status like Indonesia and East Timor, and did not have to attend as members of a Vanuatu delegation as they had in the past. And the very act of deliberating on West Papua’s application and deciding to send the FMM to Indonesia appeared to indicate of a new approach to West Papua amongst MSG states.

Two key factors however, are proving sticking points for the WPNCL’s progress at the MSG, one of which the remainder of this article examines. The first is the problem of West Papuan high level representation. While the WPNCL has excellent diplomatic networks within the MSG, and is the umbrella organisation for some 29 independence groups in West Papua, there are other influential bodies claiming to be the legitimate and most suitable representatives of West Papuans at the MSG. Jacob Rumbiak of the Australian based West Papua National Authority and the West Papuan provisional government, the Federal Republic of West Papua48, put forward a claim for MSG observer status, on behalf of his affiliations, and was present at the June summit. According to Vanuatu Lands Minister and West Papua supporter, Ralph Regenvanu, this contention around ‘true’ representativeness is disconcerting to MSG leaders, and it has weakened the WPNCL’s MSG support base49. This is an important issue that deserves detailed analysis elsewhere. But the second problem for the WPNCL, which is taken up here, is Indonesia’s powerful counteroffensive to the MSG’s new receptiveness towards West Papua50. According to an article in the Solomon Star News, Jakarta’s method is to “convince the [MSG] countries that Indonesia is a gateway to an Asian economic miracle and they can be part of the economic prosperity through Indonesia”51. In the next section, we consider the effects of Indonesia’s response on each MSG member country, the MSG overall and West Papua’s political future.

Fiji

Indonesia was savvy in determining how to pick off MSG member support for West Papua. It chose Fiji, arguably its closest Melanesian ally, as the member through which to extend an invitation to the MSG to visit West Papua, assuming correctly that Fiji’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, would take it upon himself to shore up support amongst the MSG members for an Indonesia-friendly outcome52. Having already established close military ties with Indonesia53, Fiji was also seeking closer diplomatic ties with that country after joining the Non-Aligned Movement in 2011. Brij Lal contends that Fiji is keen to assert itself on “the bigger stage” with major Asian powers but, in doing so at the expense of West Papua, is jeopardising Melanesian regional peace and security54. However, the timing of Fiji and Indonesia coming together indicates it may have triggered a foreign policy coup for Fiji, namely a visit in early 2014 by Australia’s Foreign Minister Julie Bishop to Fiji’s Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama which signified a thaw in the seven year freeze on diplomatic relations between the two countries55. In light of these prior connections with Indonesia, Fiji proved reluctant at the 2013 MSG summit to sign off on West Papuan MSG membership, instead moving to delay the decision until after the MSG Foreign Ministerial Mission (FMM) visit to West Papua in order to establish the WPNCL’s representativeness of West Papuan independence groups.

Even a last minute announcement by Indonesia that it planned to truncate the MSG delegates’ visit to West Papua—initially planned to span a couple of days, prompting Vanuatu to pull out of the trip altogether—did not cause Fiji to question the mission’s merit. Indeed, the “carefully choreographed” half-day visit to West Papua was structured so that MSG delegates did not meet with independence advocates or political prisoners in West Papua56, and therefore could not report to their constituencies on local West Papuan concerns or unrest. All of the MSG delegates who attended the Indonesian FMM visit signed, together with Indonesian officials, a statement committing each party to respect each other’s “sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity and […] non-interference in each other’s internal affairs”. This marked a sharp departure from the commitment to West Papuan self-determination made just seven months earlier at the MSG summit in Noumea. An examination of the MSG-Indonesian statement reveals a likely motive for the change of heart: it promises cooperation between the MSG countries and Indonesia on food security, trade, education, natural disaster response, policing and political and cultural exchange programs57. During the June 2014 Fiji-hosted Pacific Islands Development Forum, then-Indonesian President Yudhoyono indicated that Indonesia had earmarked US$20 million for capacity building programs for Pacific Islands countries58. These are areas in, and funds through which, individual MSG countries hope to benefit through collaboration with Indonesia.

In an attempt to further secure Fiji’s loyalty, Jakarta has showered Fiji with gifts of money and political support that have benefited both parties. One such example is Indonesia’s May 2014 US$30,000 contribution to assist Fiji in hosting the UN regional conference of the UN’s Special Decolonization Committee – a conference at which Indonesia was anxious to bury the issue of West Papua59. It has also donated one million dollars to the establishment of an MSG regional police force training academy, in which Fiji is taking a lead60. In early 2014, Vanuatu announced it would host a special meeting of the MSG to discuss West Papua after the FMM visit failed to make genuine contact with West Papuans on the ground61. Realising then that it needed Fiji’s support more than ever, Indonesia subsequently sent an eight member delegation to give public lectures at Fijian universities and to discuss “trade, investment, economic relations and even higher education prospects”62. Despite West Papuan WPNCL members labelling this a conflict of interest, the Fijian High Level Representative at the MSG, Kaliopate Tavola, commended Fiji for taking the opportunity to seek bilateral agreements with Indonesia during the FMM visit63.

However, not all Fijians are happy with the approach their Prime Minister and Foreign Minister are taking on West Papua. For example, popular Fijian musicians have collaborated to write and perform the song ‘Let the Morning Star Rise’, which refers to West Papua’s national flag, and lyrically rallies Melanesian support for West Papuan freedom64. At a national government level, too, there is discontent about the handling of West Papua: a spokesperson for Fijian opposition party the United Front for a Democratic Fiji has accused Indonesia of meddling in Fijian internal affairs by offering support for Fijian Prime Minister Commodore Bainimarama in anticipation of his re-election that occurred in September 2014, and buying off support for West Papuan self-determination65.

|

New Guinea island divided between Papua New Guinea and West Papua (or the Indonesian provinces of Papua and Papua Barat). Image credit |

Papua New Guinea (PNG)

PNG, the host of the inaugural MSG summit in 1986, and the largest country in Melanesia, is perhaps the most politically influential as well as populous member of the group. With regard to support for West Papuan independence, it is also the most reserved. PNG shares a border with Indonesia (West Papua) and its army is outnumbered 322 to one by Indonesia’s66, factors which explain PNG’s reticence to challenge Indonesia on its neighbour’s plight. The 1986 Treaty of Mutual Respect, Friendship and Cooperation between PNG and Indonesia, a bilateral non-aggression pact, governs border relations. PNG Prime Minister Peter O’Neill has been conscientious in condoning Indonesia’s “sovereignty” in West Papua, probably in the hope of reducing the border skirmishes and incursions by Indonesian troops into PNG that occur several times a year, in spite of the 1986 treaty. There are also many economic and development opportunities for PNG to exploit through collaboration with Indonesia; in 2013 PNG agreed to work with Indonesia on joint border gas exploration, highway construction and hydropower projects67. And perhaps PNG is mindful of its own secessionist issue in Bougainville, seeing any success for West Papua as a query against its own handling of the Bougainville conflict.

At the 2013 MSG summit PNG’s previous prime minister and one of the founders of the MSG, Michael Somare, addressed those gathered: “There is strong and growing support among the MSG peoples for West Papua’s membership to MSG and West Papua’s aspirations to self-determination. … For me personally, I believe that MSG should actively make representations to Indonesia to address human rights abuses in West Papua”68—because West Papua is “a significant Melanesian community”69. However, PNG’s current prime minister, Peter O’Neill, did not even attend the summit. Instead, he was leading a delegation of PNG leaders to Indonesia for discussion of border controls, trade and investment. While there, O’Neill reiterated to the Indonesian press that PNG is committed to supporting West Papua as a part of Indonesia70.

PNG’s Foreign Minister, Rimbink Pato, visited Indonesia and West Papua for the FMM, together with the Foreign Ministers of Fiji and the Solomon Islands and a representative of the FLNKS. When quizzed by media on human rights violations in West Papua he responded, “I have not seen the evidence. As I’ve said, we have a clear mandate and we have conducted an investigation … our mission has been completed”71. And while in Jayapura, West Papua, Pato reaffirmed that the MSG members “support Papua to remain under Indonesian sovereignty”72. On December 1, 2013, Powes Parkop, the governor of the National Capital District and a long-term supporter of West Papua, arranged for the Morning Star flag to be raised, as is West Papuan tradition on that date, at City Hall in Port Moresby for the first time. Prime Minister O’Neill asked Parkop to cancel the flag-raising but the governor ignored the request, accusing O’Neill of being leant upon by Indonesia. Two foreign invitees to the event, Jennifer Robinson, a prominent human rights lawyer, and Benny Wenda, a West Papuan political refugee in exile, were threatened by police with arrest warrants for taking part in political activity on a visitor’s visa73. Nevertheless, civil society and local and opposition politicians in PNG support West Papuan independence. The Melanesian United Front launched a campaign and petition to support the WPNCL at the MSG74, and the leader of the opposition in PNG, Belden Namah, recently stated: “Papua New Guinea has a moral obligation to raise the plight of West Papuans and their struggle for independence with the Indonesians and before international bodies and forums”75.

Solomon Islands

Jason MacLeod contends that “of all the Melanesian countries, the Solomons have the lowest level of awareness of the Indonesian government’s occupation of West Papua” and that “they are the site of substantial Indonesian and Malaysian logging interests”76. Indonesia and the Solomon Islands also collaborate on issues of energy, fishing, media and development77. Nevertheless, prior to leaving for the June 2013 summit, the Solomon Islands Prime Minister Gordon Darcy Lilo publicly admitted his concern for West Papuans’ human rights, stating his belief in the importance of the issue being raised at the MSG78. Furthermore, at a meeting with a delegation from the WPNCL in early 2013, he stated that “the West Papuan case is an incomplete decolonisation issue; it has been going on for too long; it must be resolved now”79.

Even at the June 2013 summit meeting, the Solomons delegation, together with Vanuatu and the FLNKS, supported the WPNCL’s MSG membership application. During the summit, Lilo expressed hope that the MSG could “provide a platform for dialogue between West Papua and Indonesia … to allow for responsible and managed progress towards self-determination”80. A trip to Indonesia by Lilo shortly after the summit, however, marked a turning point in the Solomons’ endorsement of West Papuan aims. The trip was allegedly paid for by Indonesia, and Lilo described it as a “breakthrough moment” from which “benefits will come over time”81. According to news reports, Indonesia’s then-president Yudhoyono used the opportunity to convince Lilo that prosperous development was transpiring in West Papua, and to emphasise the benefits to the Solomon Islands of ongoing trade with Indonesia82. Given the proximity of the invitation to the 2013 MSG summit and that Lilo was the first Solomon Islands prime minister ever to visit Indonesia, it seems apparent that the trip was an Indonesian attempt to sway Lilo from his pro-West Papua position.

There was civil society backlash, however, against the Solomon Islands government’s about face on the issue. Solomon Star News headlines described Lilo as having been “lured” by Indonesia into changing his position on West Papua, signifying media distrust of Indonesian motives83. And Redley Raramo, president of Forum Solomon Islands International, alleged that Lilo should be “blasted” for undermining the West Papuan agenda at the MSG summit84.

New Caledonia’s Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS)

New Caledonia is a French territory but the FLNKS (Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front) has enjoyed MSG support from the beginning, and New Caledonia is listed as a non-self-governing territory with the UN’s Decolonization Committee. Thus the FLNKS has a fine line to walk on West Papua. Caroline Machoro-Regnier, Chair of the MSG Foreign Ministers group, declared FLNKS support for West Papua at the 2013 summit, and revealed that the West Papua issue was raised at this particular summit at the FLNKS’ behest: “We asked the representatives of West Papua to come to New Caledonia to explain the situation to us. We cannot just leave the issue aside, with all the exactions, the violation of human rights that West Papua is suffering”85. However, in adding that the issue was “sensitive”, with the potential to cause a rift between MSG members and between the MSG group and Indonesia, she hinted that FLNKS loyalty to West Papua might waver, depending on the extent of the threat to MSG solidarity86.

Yet it was the MSG chairperson and FLNKS spokesperson, Victor Tutugoro, who called for a special MSG meeting to discuss West Papua just days after the FMM team returned from Indonesia because the stated aim of the visit, to meet with indigenous West Papuan human rights groups to determine the representativeness of the WPNCL, had failed. However, the Kanak delegate who completed the FMM visit, Yvon Faua, was pessimistic about the WPNCL’s prospects, stating that there were other groups claiming to represent West Papuans and that subsequently “the report FLNKS has to make to the leaders is that it is not possible to accept the application. I think the [WPNCL] has to join all the others because as we know there are also other organisations”87. The FLNKS’ post-FMM reticence to support West Papua’s bid might reflect influence from other MSG delegates, influence from Jakarta or genuine confusion as to the WPNCL’s representativeness, given that the FMM delegates were not able to meet with West Papuan independence leaders in-country. Or, as the FLNKS enter the final phase of the Noumea Accord during which they decide whether a referendum on independence will be held in 2018, it might just be that the FLNKS leaders are fearful of losing MSG support for their cause as the West Papua issue promises to be an ongoing and possibly explosive one for the organisation.

|

Rally for West Papuan independence in Port Vila, Vanuatu, March 5 2010. Image credit: Asia-pacific-action.org. Original image location |

Vanuatu

The Vanuatu Government has long been a supporter of the West Papuans and their desire for independence. This is more than a sentiment held by the political elite but is felt strongly throughout the society, more than in other Melanesian countries. Even at the time of Vanuatu’s independence, in 1980, West Papua was a significant fixture on the political landscape. Vanuatu’s first prime minister, Father Walter Lini, said that the country would never be truly free while other parts of Melanesia, especially West Papua, remained occupied by foreign powers.

How this sentiment became established in Vanuatu is unclear. Certainly amongst the general population there is a belief that the island of New Guinea is the ‘mother country’. This is true; humans arrived some 3,000 years ago, migrating down the spine of the New Guinea archipelago and onto the fertile chain of islands that today comprise Vanuatu. So there is a sense of kinship and common heritage which is deeply felt.

Moreover Vanuatu has also always been a place of refuge for West Papuan dissidents and independence activists. In the 1970s the famous West Papuan rock band, the Black Brothers, sought asylum in Vanuatu and lived there for many years. Their music, heavily imbued with a longing for independence and politically charged with themes of injustice and resistance against oppression, seeped into the consciousness of the newly independent nation88. Vanuatu continues to act as a refuge for West Papuan activists: Andy Ayamiseba of the Black Brothers has been a long term resident under successive administrations, as was John Otto Ondawame, Vice-Chairman of the WPNCL, until his passing in September 2014.

The ongoing presence of high profile West Papuan activists in Vanuatu has helped ensure that the West Papuan issue has been aired in the local media much more than in other Melanesian countries. The issue of West Papua is strongly embedded within the national psyche and on the domestic political agenda. The Vanuatu traditional Council of Chiefs, which at times of political crisis has proved to be Vanuatu’s supreme repository of political power, is also vocal in its support for West Papua, and the issue has percolated down through society from the elite to the village level.

Indonesia has been aware of this support within the Vanuatu body politic for many years, but has only recently sought to counter it. The most obvious example of this was in the courting of one of Vanuatu’s previous prime ministers, Sato Kilman, with lavish trips to Jakarta and talks of a closer relationship between the two countries. Kilman was forced to resign on March 21, 2013 ahead of a vote of no confidence largely due to his dealings with the Indonesians89. He had been instrumental in Indonesian obtaining observer status in the MSG, and Ni-Vanuatu voters believed that he was too close to Jakarta, whose influence on Vanuatu’s internal politics was feared90.

Kilman’s successor as prime minister, Moana Carcasses Kalosil, immediately distanced himself from the Indonesian push for closer ties and instead embraced the attempts to have an official West Papuan presence in the MSG. He asked the WPNCL to formally apply for observer status and facilitated the lobbying efforts of Ayamiseba and Ondawame with the governments of PNG, the Solomon Islands and Fiji. Initially these efforts seemed to make considerable headway but, as discussed above, were stymied at the MSG Noumea meeting in June by the deferral of the decision pending the MSG FMM to West Papua.

Meanwhile Kalosil continued pushing the West Papuan cause even after its support in the MSG faltered. At the United Nations on the 28th of September, 2013 he opined, “How can we then ignore hundreds of thousands of West Papuans who have been brutally beaten and murdered?”91. Kalosil went even further on March 4th, 2014 in a speech to the UN Human Rights Committee in Geneva, when he specifically referred to the horrific torture and murder of individual West Papuans which had been filmed by soldiers, and called for the Committee to establish a country mandate which should “include investigation of alleged human rights violations in West Papua and provide recommendations on a peaceful political solution in West Papua”92.

Indonesia responded forcefully to Kalosil’s speech and the accusation of human rights abuses. It is worth looking at this response in some detail as it clearly states the Indonesian government’s view on West Papua. It is also demonstrated the importance of the FMM’s trip to West Papua as a piece of diplomatic window dressing. Using the right of reply, Indonesia’s Ambassador to the United Nations rejected Kalosil’s claims:

His statement represents an unfortunate and sadly lack of understanding of basic facts on historical role of the UN and the principled position of international community at large as well as the current state of Indonesia, including the actual development in the provinces of Papua and West Papua, Indonesia93.

The Indonesian Ambassador then went on to claim that the “issue of West Papua” was manipulated within Vanuatu’s domestic politics for electoral advantage by certain individuals. Quoting former Prime Minister Sato Kilman (who, as noted, lost office due to his close connection with Jakarta) as saying: “In Vanuatu, the West Papua issue has been politicised and used by different political parties and movements not for the interests of the people in West Papua but more so for elections and political campaign propaganda”. The Ambassador then alluded to the farcical FMM mission discussed above, which spent less than a day in West Papua, as undermining Kalosil’s comments:

Furthermore, the statement of Mr. Kalosil is simply in contradiction with the visit of a high-level delegation of the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) members representing Melanesian Community to Indonesia from 11 to 16 January 2014 in which Ministerial Level Delegation of Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and representative of the Front de Liberation Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS) of New Caledonia as well as MSG High Representative conducted in situ visit to Papua province and obtained firsthand information94.

Finally the Ambassador referred to one of the agreements signed by Kilman as Prime Minister, as being somehow breached by Kalosil’s statement:

Worse, his statement is also in contradiction to the will of the Vanuatu government itself towards its relation with Indonesia as reflected in the 2011 Bilateral Development Cooperation Agreement that provides a legal framework for the two countries to respect each other’s sovereignty, unity, and territorial integrity and principles of non-interference in each other’s internal affairs95.

This open diplomatic confrontation was evidence that Indonesia’s diplomatic offensive over West Papua was well underway. Despite the heartfelt support for the West Papuan struggle within the Vanuatu government and the country as a whole, this sentiment is much weaker in the other Melanesian countries. Their support for the cause has waned as their financial and strategic relationship with Indonesia has blossomed, and it is hard to separate these two developments. The financial and strategic support from Indonesia can be clearly linked to the withdrawal of support by the MSG states for West Papua. The clearest example of this has been Fiji.

|

Bainimarama and Yudhoyono. Image credit |

Indonesia-Fiji Diplomatic Entente

Fiji had been one of the MSG countries actively promoting the membership of West Papua, or at least its ‘observer status’, which Indonesia also enjoys. The late WPNCL leader, John Otto Ondawame, had an enthusiastic response from Fiji Prime Minister, Bainimarama, when he visited Suva for talks with the Fijian government over the proposed MSG membership in March 2013. However these talks did not ultimately result in Fijian support for the Papuans’ MSG bid.

Fiji had been suspended from the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) in 2009 under pressure from Australia and New Zealand following Bainimarama’s coup in 2006. This was an attempt, along with other sanctions, to diplomatically isolate Fiji and the Bainimarama regime until free and fair elections were held for a new government. Bainimarama responded by forming a rival organization to the PIF, the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF), which had its inaugural meeting in Suva in early August 2013, to which Australia and New Zealand were not invited96.

While regional concerns about the Bainimarama regime are legitimate, Fiji also has well-founded grievances against Australia and New Zealand. Pacific countries often felt that the PIF was dominated by the ‘big two’ whose economic, military and diplomatic power dwarfed the many small nations of the Pacific. Serious concerns among Pacific nations, such as restrictive visa policies, the threat of climate change and rising sea levels, and the offshore processing of asylum seekers, were brushed aside by Australia. While Australian development aid is substantial to all the PIF countries, many policies pushed by Australia, such as the registration of traditional land as a precursor for its commodification and possible sale (leaving Pacific Islanders landless), are strongly resisted by many Islanders, and also deeply resented as external interference in purely domestic issues.

While the PIDF may have had a degree of legitimacy amongst some Pacific nations it was the role played by Yudhoyono at the PIDF forum in June 2014 which transformed the nascent organisation into one which threatens the established architecture of international relations in the South Pacific.

Even before the PIDF meeting Indonesia was maneuvering to suppress the West Papua issue. The Vanuatu’s Daily Post newspaper saw Indonesia’s US$30,000 contribution to Fiji to help fund hosting the United Nation’s regional meeting of the Special Decolonization Committee as blatant manipulation: “Jakarta’s cheque book diplomacy reflects its determination to silence any murmurs of regional support or discussions within the MSG on the issue of re-enlisting West Papua back on the decolonisation list”97. It seems to have been money well spent for Indonesia as there was scant mention of West Papua in the official forums, despite local moves by some church groups to have the issue aired.

The depth of Indonesian engagement with Fiji became apparent at the PIDF held on June 17-19, 2014. Yudhoyono was the chief guest and keynote speaker at the event, which focused on climate change and sustainable development. It was the first visit to Fiji by a serving Indonesian president and the length of the stay – three days – shows just how important the Indonesians judged the event. Espousing the benefits of a closer relationship between Indonesia and the Pacific Island states, Yudhoyono made firm commitments to increase aid and engagement. Amongst other things he promised US$20 million over five years to address the challenges of climate change and disasters; talked of plans to triple trade to a billion dollars in coming years, and outlined how Indonesia could act as a bridge for the Pacific and Indian Ocean states98. Yudhoyono suggested Indonesia would become the conduit by which the Pacific Island states (especially Fiji) could interact with the dynamic Asian region and the wider world.

The PIDF meeting also seemed to acknowledge the ‘terms of trade’ of the Indonesian-MSG states relationship: on the one hand there would be silence by the Pacific leaders on West Papua, and on the other hand (as ex-Editor of the Fiji Times, Netani Riki, put it) Indonesia “would not rock the boat on questionable governance, transparency and human rights issues”99. This Faustian pact should have had alarm bells ringing in Canberra; there are already voices of concern being raised in the Pacific. Reverend Francois Pihaatae, General Secretary of the Pacific Council of Churches, commented, “Where our self-determination interests are concerned, whether it be in the areas of governance, development and security, or our firm support for West Papuan freedom, we cannot allow the state visit to cloud our prudence and better judgment”100.

This is the core of the conundrum. It is no secret that the Melanesian countries have serious problems with poor governance and widespread corruption. There are human rights abuses outside of West Papua, with Fiji itself being virtually a military dictatorship. The MSG countries need more transparency, not less since it is one of the few effective remedies for reining in corruption, along with an independent judiciary. In PNG billions of dollars of foreign aid and a recently resurgent economy have not translated into improved living standards and better public services for the majority of people. In many areas, such as the Sepik River region, basic services have gone steadily backwards since independence. The chief explanation for this is poor governance and corruption.

Bainimarama was ecstatic over the success of the PIDF meeting and Yudhoyono’s visit. He called it “one of the greatest things that has ever happened to Fiji”101. Yudhoyono must have been highly pleased with the visit too: there had been no mention (at least publicly) of West Papua, and the substitution of Indonesia in the ‘big brothers’ role traditionally played by Australia, New Zealand and the US was being openly discussed. For Bainimarama there was an added bonus: it was agreed Indonesia would co-lead the multi-national group of observers that monitored Fiji’s September 2014 general election. As it turned out, Bainimarama retained the premiership102.

Bainimarama’s diplomatic maneuverings also continued within the MSG, of which Fiji had Chairmanship during 2012-2013 leading up to the Noumea summit. As mentioned, the MSG had been originally formed to support the FLNKS in New Caledonia and their desire for independence from France. However the MSG diminished in importance after the Matignon Accord was signed in 1988, which allowed for a referendum on New Caledonia’s future after ten years. During this period the New Caledonians agreed not to raise the issue of independence. Bainimarama reinvigorated the MSG by bringing the issue of West Papuan membership into the mix before doing an about turn and getting closer to Jakarta.

The Decision

As discussed, the prospective membership of the WPNCL in the MSG was deferred in June 2013 pending the FMM fact-finding trip to Indonesia in January 2014. The MSG’s decision was formally announced at the MSG meeting in Port Moresby on June 26, 2014. As a result of Indonesia’s successful intervention into Melanesian regional politics, the application by the WPNCL was rejected. The official communique announced that:

8. The Leaders:

(i) Noted and accepted the contents of the Ministerial Mission’s Report;

(ii) Agreed to invite all groups to form an inclusive and united umbrella group in consultation with Indonesia to work on submitting a fresh application;

(iii) Welcomed and noted the progress on greater autonomy in Papua and the recent announcement by the President of Indonesia to withdraw the military from West Papua;

(iv) Endorsed that the MSG and Indonesia take a more proactive approach in addressing the issue of West Papua and Papua by undertaking the initiative to conduct greater awareness on the situation in Papua and West Papua Provinces with respective to the Special Autonomy Arrangements and how this has contributed positively to the Governance of the Provinces by the local population;

(v) Endorsed that the MSG continue to hold dialogue with Indonesia on the issue of West Papua and Papua and encourage and support the establishment of bilateral cooperation arrangements with Indonesia with specific focus on social and economic development and empowerment for the people of Papua and West Papua Provinces;

(vi) Endorsed that MSG Members and Indonesia consider holding regular Meetings at Ministerial and Officials level to discuss (iv) and (v);

(vii) Endorsed that MSG in consultation with Indonesia work together in addressing the development needs of the Papua and West Papua Provinces;

(viii) Endorsed that MSG encourage the strengthening and participation of Melanesians in Indonesia in MSG Activities and Programmes; and

(ix) Endorsed that the MSG continue to support and encourage the level of Melanesian involvement in executive, management and controlling positions in private enterprises such as the Bank of Papua and at political levels103.

This represents a substantial victory for Indonesian diplomacy in thwarting WPNCL attempts to join the MSG. The decisions taken by the MSG, in effect, give the Indonesian government a veto over MSG policy on West Papua. Apparently West Papuan membership will only be reconsidered if the competing Papuan independence groups: the WPNCL and the Federal Republic of West Papua (FRWP), the influential activist movement the Komite Nasional Papua Barat (KNPB) and the pro-Indonesian West Papuans, as well as Melanesians from other parts of Indonesia, collectively put in an application, with the approval of the Indonesian government. Given the deep antagonisms among these various groups and the individuals who lead them, a united application will be a difficult undertaking, although in a seminar at the University of Sydney on June 30, 2014 West Papuan ‘dialogue’ diplomat Octo Mote spoke of the recently articulated willingness of WPNCL leaders, leaders of the FRWP within West Papua, and those of the KNPB to work together in this regard. The longstanding opposition of Jakarta to the inclusion of West Papua in the MSG will also obviously be a barrier, although, according to Mote, West Papuans can appeal to the MSG that the FLNKS did not need France’s approval to join the MSG so why should West Papua need Indonesia’s?

On the other hand, optimists have expressed the view that this potential unity grouping may be able to create a forum in which serious negotiations could take place between the various segments of West Papuan society and the Indonesian government104. While this may appear unlikely, the diplomatic power plays between the Pacific nations and Indonesia are far from over. Vanuatu, which has always supported the WPNCL and boycotted the FMM, continues to advocate on West Papuas’ behalf. Recently installed Vanuatu Prime Minister, Joe Natuman, has raised the prospect of referring the case of West Papua to the International Court of Justice, declaring: “We consider seeking an opinion on the legal process held by the UN when it handed over West Papua to Indonesia”105. The announcement of a Reconciliation Conference to be held in Port Vila in August 2014 between the various West Papuan groups, who are still hopeful of jointly gaining a place at the MSG table, shows that this process is far from over106. Indeed there is something intrinsically Pacific about how the negotiations are unfolding in the face of the seemingly insurmountable communique issued by the MSG excerpted above.

Of course there are other major players in the Pacific region, particularly the US with its own hegemony over the Micronesian countries and sovereign status over the Hawaiian Islands, although the US does not play a significant role in MSG diplomacy. China is also engaged in the region, with multiple interests in PNG from the ownership and management of mines such as Ramu Nickel to a voracious appetite for raw materials, including timber. As in many other regions, China is also purchasing both agricultural and residential real estate, especially in countries amenable to foreign investment such as Vanuatu. Yet these players have been much more cautious in straying into the domestic politics of individual countries. They do not have the over-riding motivation that Indonesia has to thwart the activities of West Papuan independence activists.

Conclusion

In the current state of Melanesian regional politics, it appears that the cultural and historical affiliations of West Papuans with other Melanesians are threatened by regional realpolitik. The MSG’s decision regarding West Papua’s status has a diplomatic veneer but a duplicitous core—without directly rejecting any future West Papuan bid for membership the MSG has placed seemingly insurmountable obstacles in the way. Jakarta can be satisfied that its policy of engagement with the MSG has so far yielded the hoped for results. However, West Papuan independence activists continue to maneuver for official status in the MSG, buoyed by the considerable sympathy and support that many organisations and individuals have for their cause.

Fiji’s PIDF may cement West Papua’s hyphen status between Asian Indonesia and the non-Anglo Pacific, sacrificing Melanesian solidarity with West Papua for assumed economic benefits and closer political ties with Indonesia. But ignoring Indonesia’s undemocratic actions in West Papua is unlikely to yield a more peaceful and democratic region. Thus, while Melanesia’s regional elites may have taken the lead in fostering the region’s cultural identity during decolonisation, Melanesia’s burgeoning civil society now has a significant role to play in pressuring their governments to promote the West Papuan cause. The MSG has reached a turning point and must decide whether it values West Papuan human rights over the potential economic benefits of increasing political engagement with Indonesia.

Camellia Webb-Gannon is a Research Fellow at the Justice Research Group at the University of Western Sydney and is the Coordinator of the West Papua Project at the University of Sydney. Camellia received her PhD in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of Sydney in 2012 with a thesis examining the dynamics of unity and conflict within West Papua’s independence movement. Her recent research considers the impact of digital technologies on human rights advocacy as well as local interpretations of Melanesian indigenous rights, Melanesian self-determination movements, and concepts and mechanisms of justice in the Pacific region. [email protected]; @camwebbgannon

Jim Elmslie is a Visiting Scholar and co-convener of the West Papua Project, the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Sydney. His PhD entitled Irian Jaya Under the Gun: Indonesian Economic Development versus West Papuan Nationalism, was published by the University of Hawaii Press. Jim has been closely involved with the Sepik River region of PNG since 1983 as a political economist, tribal art dealer, film consultant and cultural advisor. [email protected]

Recommended citation: Camellia Webb-Gannon and Jim Elmslie, “MSG Headache, West Papuan Heartache? Indonesia’s Melanesian Foray”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 47, No. 3, November 24, 2014.

Notes

1 Margaret Jolly notes that Pacific scholars such as Epeli Hau’ofa prefer the term ‘Oceania’ for the region that encompasses the Pacific and parts of Asia. Although originally a colonial label, ‘Oceania’ has been endogenised and claimed by Pacific Islanders in contrast to the term ‘Asia-Pacific’ which derives from foreigners’ ‘policy speak’ (see also Arif Dirlik, 1992. ‘The Asia Pacific Idea: Reality and Representation in the Invention of a Regional Structure’, Journal of World History 3:1, pp. 55-79) and carries hegemonic connotations (Margaret Jolly, 2008. ‘The South in Southern Theory: Antipodean Reflections on the Pacific’, Australian Humanities Review 44).

2 Indonesian senior government advisor Dewi Fortuna Anwar has justified this approach, claiming, “there are more Melanesians living in Indonesia, not just in Papua, than in the Pacific. We have people of Melanesian origin living in Maluku and in Ambon and in the NTT province of Indonesia” (Radio New Zealand International, Jakarta Defends Its Policy Approach in Papua Region, August 5, 2013).

3 An independence movement has been underway in the Maluku Islands since 1950 and in West Papua since 1964.

4 Michael Smith and Maureen Dee, 2003. Peacekeeping in East Timor: The Path to Independence, International Peace Academy Occasional Paper Series, Boulder; Matthew LeRiche and Matthew Arnold, 2012. South Sudan: From Revolution to Independence, Columbia University Press, New York City.

5 Chris Ballard, 1999. ‘Blanks in the Writing: Possible Histories for West New Guinea’, Journal of Pacific History 34:2, pp. 148-155.

6 There have been media, political, academic and activist initiatives such as International Lawyers for West Papua, International Parliamentarians for West Papua, several ABC national network stories on West Papua in 2012 and 2013, a US Congress hearing on Crimes Against Humanity: When Will Indonesia’s Military Be Held Accountable for Deliberate and Systematic Abuses in West Papua in 2010, and the Biak Massacre Citizens Tribunal held by the West Papua Project at the University of Sydney in 2013, to name a few examples.

7 See for example Winston Tarere’s article of May 2, 2014: ‘Indonesia Exercises Cheque-Book Diplomacy Ahead of UN Decolonization Conference’, Daily Post.

8 See Ron Crocombe, 2007. Asia in the Pacific Islands: Replacing the West, IPS Publications, Suva, pp. 301-302. While the Pacific region is the localised arena in which Indonesia and West Papua are engaged in their current power struggle, the UN has been the longest standing diplomatic battleground for attempts to establish ultimate sovereignty over West Papua. Supporters of West Papuans’ right to self-determination, including Senegal and several other African countries, registered their opposition to Indonesia’s takeover of West Papua at the UN as long ago as 1969 after a sham referendum over the territory’s sovereignty was overseen by the UN, and as recently as March 2014 when Vanuatu’s former Prime Minister Moana Carcasses Kalosil used the Human Rights Council to lambast Indonesia over its human rights violations in West Papua.

9 Papuans settled in the highlands of New Guinea between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago.

10 Austronesians came to the Pacific approximately 4000 years ago.

11 Crocombe, 2007, p. 3.

12 Clive Moore, 2003. New Guinea: Crossing Boundaries and History, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, pg. 62.

13 See for example Pieter Drooglever, 2005. An Act of Free Choice: Decolonization and the Right to Self-Determination in West Papua, One World, Oxford, p. 65.

14 The figures range, depending on whether deaths resulting from direct violence only are counted, or those following on from starvation and other forms of systemic violence are taken into account.

15 See Crocombe 2007, pp. 281-298; Carmel Budiardjo and Soei Liong Liem, 1988. West Papua: The Obliteration of a People, Tapol, London; testimonies on the Biak Massacre Tribunal website; and Elizabeth Brundige, Winter King, Priyneha Vahali, Stephen Vladeck and Xiang Yuan, Indonesian Human Rights Abuses in West Papua: Application of the Law of Genocide to the History of Indonesian Rule, Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic, Yale Law School, 2004.

16 Jim Elmslie and Camellia Webb-Gannon, 2013. ‘A Slow Motion Genocide: Indonesian Rule in West Papua’, Griffith Journal of Law and Human Dignity 2:1.

17 Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital, is separated from Jayapura, West Papua’s largest city, by 3785 kilometres, from PNG’s capital, Port Moresby, by 4,449 kilometres, from Vanuatu’s capital, Port Vila, by 6,777 kilometres, from Solomon Islands capital, Honiara, by 5,852 kilometres, from New Caledonia’s capital, Noumea, by 6,621 kilometres, and from Fijji’s capital, Suva, by 7,847 kilometres.

18 See for example Danilyn Rutherford, 2003. Raiding the Land of the Foreigners: The Limits of a Nation on an Indonesian Frontier, Princeton University Press, Princeton; and Richard Chauvel, Constructing Papuan Nationalism: History, Ethnicity and Adaptation, Policy Series 14, East West Center Washington, Washington D. C., pp. 41-47. John Conroy, on the other hand, writes that the contiguity between the Melanesian and Asian regions contributes to making the “contrasts between them more piquant” (2013. ‘The Informal Economy in Monsoon Asia and Melanesia: West New Guinea and the Malay World’, Crawford School Working Paper, The Australian National University, Canberra, pg. 6).

19 See David Webster, 2001-2. ‘Already Sovereign As A People: A Foundational Moment in West Papuan Nationalism’, Pacific Affairs, 74:4, pp. 507-528.

20 See Roger Keesing and Robert Tokinson (eds), 1992. ‘Reinventing Traditional Culture: The Politics of Culture in Island Melanesia’, Special Issue, Mankind 13:4; one example of invented national tradition in West Papua is the Yospan dance, made up of dance steps from Biak and an area near Jayapura—see Rutherford, 2003, pp. 99-105.

21 See for example Ronald May on Melanesian ‘political style’: 2004. ‘Political Style in Modern Melanesia’ in State and Society in Papua New Guinea: The First Twenty-Five Years, ANU E-Press, Canberra; and Clive Moore on Melanesian wantokism, or the preferential treatment of those with whom you identify most according to common language, or in a wider conception, at nation-state or regional levels: 2008. ‘Pacific View: The Meaning of Politics and Governance in the Pacific Islands’, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 62:3, p. 392.

22 Crocombe, 2007, p. 296.

23 Feminist Media Studio, ‘James Clifford On ‘Becoming’ Indigenous’, Vimeo Interview.

24 Margaret Jolly, 2007. ‘Imagining Oceania: Indigenous and Foreign Representations of a Sea of Islands’, The Contemporary Pacific 19:2 p. 521.

25 Interview with Selwyn Garu, Port Vila, Vanuatu, July 20, 2009

26 Lawson, 2013, p. 22.

27 Ibid, p. 22.

28 Indonesia derives much of its revenue from the largely United States-owned gold and copper mine Freeport McMoRan operating in West Papua, depends on West Papua for relieving overpopulation on Indonesian islands, uses West Papua as roaming ground for its defense force, and takes national pride in its ‘territorial integrity’—West Papua inclusive.

29 Fiji has historically tended to identify with a “Pacific Way” which favours Polynesian cultural identifiers. Fiji did not join the Melanesian Spearhead Group until 1996, 10 years after the Group’s formation, when its regional identification began to shift (see Lawson, 2013, p. 19).

30 See Epeli Hau’ofa, 2008. We Are the Ocean: Selected Works, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu; Jean-Marie Tjiabou, 1996. Kanaky, Pandanus Books, Canberra; Bernard Narokobi, 1983. The Melanesian Way, University of the South Pacific, Suva; and Jolly, 2008.

31 Ronald May, 2004. State and Society in Papua New Guinea: The First Twenty-Five Years.

32 See Lawson 2013, p. 2 and p. 21.

33 Ibid, p. 14.

34 See Tracy McFarlane, 2010. ‘Experiencing Difference, Seeking Community: Racial, Panethnic, and National Identities among Female Caribbean-Born US College Students’, American Review of Political Economy 8:2, p. 101.

35 See Narokobi, 1983.

36 See Lawson, 2013, p. 17.

37 Ibid, p. 15.

38 See Narokobi, 1983, pp. 49-57; and Lawson, 2013, p. 12.

39 Crocombe, 2007, p. 301.

40 Kirsten McGavin, 2014. ‘Being ‘Nesian’: Pacific Islander Identity in Australia’, The Contemporary Pacific 26:1, p. 126.

41 MacFarlane, 2010, p. 101.

42 For example, HIV infection rates in the province are 40 times the Indonesian national average (see S. Rees and D. Silove, 2007. ‘Speaking Out About Human Rights and Health in West Papua’, The Lancet 370(9588) pp. 637-639; for another example, indigenous West Papuans have an infant mortality rate of 18.4 per cent, whilst the infant mortality rate among the non-indigenous population in West Papua is 3.6 per cent—see Stella Peters and Wouter Bronsgeets, 2012. ‘Extremely High Infant Mortality in West Papua Result of Discrimination’ Press Statement from 12 November 2012.

43 Public Institute of Pacific Policy, 2008. ‘MSG: Trading on Political Capital and Melanesian Solidarity’, Briefing Paper 2.

44 The FLNKS is the only member of the MSG that is not a state, but an indigenous political organization.

45 Radio New Zealand International, June 6, 2013. ‘FLNKS Formally Invites West Papua to Attend MSG Meeting’, Islands Business.

46 See Jennifer Robinson, March 21, 2012. ‘The UN’s Chequered Record in West Papua’, Al Jazeera.

47 West Papua National Coalition for Liberation, June 2014. ‘MSG Update’, Morning Star Newsletter 6:1.

48 However, as Jason MacLeod notes, when the President of the Federal Republic of West Papua, the incarcerated Forkorus Yaboisembut, heard of the WPNCL’s application, he wrote to the Director General of the MSG withdrawing his government’s application and offered support for the WPNCL (see Jason MacLeod, July 1, 2013. ‘A Win For West Papua In Melanesia’, New Matilda).

49 Australian Association for Pacific Studies, April 24, 2014. ‘Q&A with Ralph Regenvanu, Session on West Papuan Activism. The University of Sydney. Similar issues plagued the East Timorese independence political party, FRETILIN (and various of the other East Timorese resistance groups), from the 1970s to the 1990s, due to continued ambushes by the Indonesian military, ideological differences, and personal leadership feuds (Charles Call, 12. Why Peace Fails: The Causes and Prevention of Civil War Recurrence, Georgetown University Press, Washington D.C., pp. 137-138.

50 MacLeod writes that Indonesia was sufficiently worried about MSG support for West Papua that for the first time ever it invited five governments to observe Papua/West Papua (see Jason MacLeod, July 1, 2013. ‘A Win For West Papua In Melanesia’, New Matilda).

51 Solomon Star News, August 15, 2013. “Lilo Lured by Indonesian President”, Solomon Star News.

52 Winston Tarere, February 27, 2014. ‘Vurobaravu better placed to deal with West Papua at the MSG’, Daily Post.

53 Kiery Manassah, February 2014. ‘The MSG Knows It Has Unfinished Business Regarding West Papua’, Public Institute of Pacific Policy.

54 Johnny Blades, July 23, 2013. ‘One Voice: West Papua’s Demand for Greater Independence Has Not Gone Unheard By Other Melanesian States”, The Guardian.

55 Rowan Callick, February 15, 2014. ‘Julie Bishop Move to Bring Fiji in From Cold’, The Australian.

56 Islands Business, February 2014. ‘MSG Cohesion in Doubt?’ Islands Business.

57 Arto Suryodipuro, January 25, 2014. ‘Building Relations with Pacific Island Countries’, The Jakarta Post.

58 Ina Parlina, June 20, 2014. ‘RI to Boost Ties with Pacific Island Countries’, The Jakarta Post.

59 Winston Tarere, May 2, 2014. ‘Indonesia Exercises Cheque-Book Diplomacy Ahead of UN Decolonization Conference’, Daily Post.

60 Ibid.

61 Tabloid Jubi, March 3, 3014. ‘Indonesia Accused of Meddling in Fiji Affairs’, Tabloid Jubi.

62 Islands Business, March 4, 2014. ‘Fijian Ties Move, Indonesians with Papuans Fly In’, Islands Business.

63 Shalveen Chand, February 10, 2014. ‘Fiji’s Tavola Defends MSG Meeting in Indonesia, Ambassador Says It Was Opportunity to ‘Seek Bilateral Agreements’, Pacific Islands Reports.

64 Seru Serevi in interview with Bruce Hill, March 3, 2014. ‘Fiji Musician Seru Serevi Releases West Papua Song’, Pacific Beat, ABC Radio Australia.

65 Tabloid Jubi, March 3, 2014.

66 Winston Tarere, February 27, 2014. ‘Vurobaravu Better Placed to Deal with West Papua at the MSG’, Daily Post.

67 Johnny Blades, July 23, 2013. ‘One Voice: West Papua’s Demand for Greater Independence Has Not Gone Unheard By Other Melanesian States’, The Guardian.

68 Nic Maclellan, June 22, 2013. ‘Somare Says MSG Must Serve the Region: West Papua Roadmap Approved’, Pacific Scoop.

69 Makereta Komai, June 20, 2013. ‘Sir Michael Somare Exhorts MSG To Include West Papua In Its Activities’, PACNEWS.

70 Islands Business, June 19, 2013. ‘West Papua Part of Indonesia: PNG PM’, Islands Business.

71 Ina Parlina and Margareth S. Aritonang, January 17, 2014. ‘Melanesians Respect RI’s Sovereignty’, The Jakarta Post.

72 Bagus Bt Saragih and Margareth S. Aritonang, January 14, 2014. ‘After Observing Papua, MSG Ministers to Meet SBY’, The Jakarta Post.

73 PNG Industry News.net, March 10, 2014. ‘Innocent Occupation’, PNGINndustryNews.net.

74 Catherine Wilson, December 29, 2013. ‘West Papua Searches Far for Rights’, InterPress Service.

75 Free West Papua.org, April 16, 2014. ‘PNG Opposition Officially Supports a Free West Papua’, Free West Papua.org.

76 Jason MacLeod, July 1, 2013. ‘A Win For West Papua In Melanesia’, New Matilda.

77 Solomon Star News, August 15, 2013. ‘Lilo Lured by Indonesian President’, Solomon Star News (link no longer live).

78 Solomon Star News, June 19, 2013. ‘PM to Introduce New Concept Paper to MSG’ Solomon Star News (link no longer live)

79 West Papua National Coalition for Liberation, June 26, 2013. ‘Statement Regarding the MSG Decision on West Papua’, Pacific Scoop.

80 Blades, July 23, 2013. The Guardian.

81 Radio New Zealand International, August 29, 2013. ‘Solomons Prime Minister Says Indonesia Will Meet All Trip Costs’, RNZI.

82 Ini Parlina, August 13, 2013. ‘Indonesia, Solomon Islands Leaders Talk About Papua’, The Jakarta Post.

83 Solomon Star News, August 15, 2013. ‘Lilo Lured by Indonesian President’, Solomon Star News (link no longer live).

84 Islands Business, June 24, 2013. ‘FSII Condemns Solomon Islands PM’s Declaration On West Papua’, Islands Business.

85 Nic Maclellan, June 18, 2013. ‘MSG to Send Mission to Jakarta and West Papua’, Island Business.

86 Makereta Komai, June 18, 2014. ‘West Papua Decision Deferred’, PACNEWS.

87 Radio New Zealand International, January 22, 2014. ‘Umbrella Papuan Group Suggested To Apply For MSG’, Pacific Islands Report.

88 Interview with John Otto Ondawame, Port Vila, Vanutau, April 12, 2013.

89 Bobakin, March 21, 2013. ‘Vanuatu PM Kilman Resigns’, Vanuatu Daily.

90 Interview with John Otto Ondawame, Port Vila, Vanutau, April 12, 2013.

91 UN News Centre, September 28, 2013. ‘Vanuatu Urges Inclusive Development, Pledges to Continue Speaking Out Against Colonialism’, UN News Centre.

92 Pacific Media Centre, March 2, 2014. ‘Vanuatu PM Blasts Indonesian Human Rights Violations in West Papua’, Pacific Media Centre.

93 Tabloid Jubi, March 6, 2014. ‘Indonesia Strongly Rejects the Statement of Prime Minister of Vanuatu’, Tabloid Jubi, link no longer live.

94 Ibid.

95 Ibid.

96 Australian Network News, August 8, 2013. ‘Inaugural Meeting of the Pacific Island Development Forum Ends with Allegations of Sabotage’, Australian Network News.

97 Winston Tarere, May 2, 2014. ‘Indonesia Exercises Cheque-Book Diplomacy Ahead of UN Decolonization Conference’, Daily Post.

98 Radio New Zealand International, June 19, 2014. ‘Indonesia to Strengthen Ties with Fiji’s PIDF’, Radio New Zealand International.

99 Neatni Rika, June 19, 2014, ‘All Aboard the Gravy Train as SBY Visits Fiji’, Crikey.com.

100 Tevita Vuibau, June 20, 2014. ‘Plea for West Papua’, The Fiji Times Online.

101 Tevita Vuibau, June 23, 2014. ‘Plea for West Papua’, The Fiji Times Online.

102 Radio New Zealand International, June 19, 2014. ‘Indonesia to Co-lead Fiji Observer Force, Radio New Zealand International.

103 Special MSG Leaders’ Summit, 26 June 2014. ‘Communique’, National Parliament, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea.

104 Radio New Zealand International, July 2, 2014. ‘Jakarta/West Papua Talks Urged’, Radio New Zealand International.

105 Tabloid Jubi, July 2, 2014. ‘The Government of Vanuatu Will Continue Raising the Issue of West Papua to the UN’, Tabloid Jubi, link no longer live.

106 Papuans believe MSG will support new application, Vanuatu Daily Post, July 8, 2014.