Korean translation available

Chan, Koon-chung. 2012. Zhongguo tianchao zhuyi yu Xianggang (China’s Heavenly Doctrine and Hong Kong). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Chin Wan. 2011. Xianggang Chengbang lun (On Hong Kong as a city state). Hong Kong: Enrich Publishing.

Jiang Shigong. 2008. Zhongguo Xianggang: wenhua yu zhengzhi de shiye (China’s Hong Kong: cultural and political perspectives). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Hong Kong has been in turmoil. The 2003 demonstration in which more than half a million demonstrators successfully forestalled the Article 23 anti-subversion legislation2, as well as the 2012 rally of 130,000 and the threat of general student strikes that forced the government to shelve implementation of a Beijing-ordered National Education curriculum in Hong Kong schools, showed that Beijing could not crack down on Hong Kong’s dissenting voices as readily as it repeatedly has in mainland China. Such resistance victories have not brought a willingness to compromise on fundamentals by either Hong Kong’s opposition forces or Beijing. On the contrary, they may have radicalized both sides. Beijing’s decision to induct hardliner CY Leung as the chief executive in 2012, despite strong opposition even from its traditional allies among the city’s tycoons, shows that it is ready to use more draconian means to deal with an increasingly bold opposition intent on upholding Hong Kong’s relative autonomy.

In the meantime, the British flag or Hong Kong flag containing the Union Jack started to appear and spread in annual July 1st and January 1st demonstrations in 2012. Slogans attacking mainland tourists and even “Chinese colonialists” surfaced.

Beijing and many pro-establishment observers sensed the emergence of a strong localist identity and even a pro-independence disposition. Besides explicit political declarations that defy Beijing rule, localist and anti-Chinese youth also initiated militant direct action. One example was the protest that sought to disrupt smuggling activities by mainland tourists to defend local supply of daily necessities, most of all baby formula, echoing the food riots in early modern Europe studied in E. P. Thompson’s seminal article “The moral economy of the English crowd in the Eighteenth century.”3 Localist demonstrations also led the Hong Kong government to restrict birth tourism from the mainland that strained the public hospital system.

Recent opinion polls show that Hong Kong identity has been surging while Chinese identity has been fading among Hong Kong residents, particularly among youth.4 Such radicalization of Hong Kong local consciousness not only irritated Beijing. It also departs from the historical domination of Chinese nationalist discourse in Hong Kong’s opposition movement, which has tended to see itself as an avatar of Chinese liberalization and democratization, since its inception in the 1980s.

The question of local identity in Hong Kong is examined from the perspectives of Beijing, Chinese nationalist liberals, and Hong Kong local youth in three recent books by Jiang Shigong, Chan Koon-chung and Chin Wan. The increasing assertiveness of Beijing as an imperial center over Hong Kong, part and parcel of the rising statism and nationalism among the Chinese elite, is epitomized by Jiang Shigong’s book. Chan Koon-chung’s and Chin Wan’s books constitute powerful retorts to Beijing’s neo-imperialist stance on Hong Kong, both explicitly challenging Jiang’s thesis. While Chan’s response resonates with the perspective of liberal intellectuals in mainland China, Chin’s response, rooted in a Hong Kong perspective, reflects the rising tide of Hong Kong localist ideology and actions.

Seeing Hong Kong like an Empire

In recent years, part of the New Left in China that critiqued American imperialism and neoliberalism in the 1990s has morphed into a peculiar intellectual formation that advocates a union of apparently conflicting intellectual lineages including Marxism and Maoism, and right-wing statism as epitomized by Leo Strauss, Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt, and Confucianism. This group of intellectuals has been criticized by liberals as being complicit or openly collaborative with the increasingly repressive party-state establishment.5

Among this group of intellectuals is Jiang Shigong. As a neo-Maoist, he fretted that Deng Xiaoping’s denunciation of the Cultural Revolution had thrown the baby out with the bathwater by erroneously discrediting the experiment in “Great Democracy” during the Cultural Revolution, depriving China of its indigenous discourse on democracy and becoming speechless in the face of the western promotion of bourgeois democracy (Jiang 2008: 187-8). At the same time, he is one of the key authors who introduced Carl Schmitt’s legal philosophy, which sees the practice of differentiating enemies from friends and the absolute decisiveness of the sovereign as being of utmost importance in politics, with priority over legal and legislative authorities. Jiang served as a researcher in the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Hong Kong, the de facto CCP headquarters in Hong Kong, between 2004 and 2007. During and after his tenure in Hong Kong, he published a series of articles articulating his views on the Hong Kong question and its significance for China’s revival as a Confucian empire in Beijing’s Dushu (Reading) magazine. The present book is a collection of those articles. While his view is not unique among the New Left, his position as the Associate Dean of the School of Law in Peking University and his earlier official affiliation with the Liaison Office in Hong Kong make him the most conspicuous voice on Hong Kong close to the party-state’s power center.

Jiang asserts that though the “one country, two systems” formula served as a brilliant arrangement that secured Hong Kong’s reunion with China in 1997, it is incapable of tackling the most important question regarding China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong, that is, the question of Hong Kong people’s identity. Jiang suggests that the solution to this question has to be sought through political rather than legal means, and Beijing has to think beyond the “one country, two systems” framework in its endeavor to transform Hong Kong residents into true Chinese patriots. Short of that, China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong can only be formal and never substantive.

Jiang believes that most Hong Kong people have embraced the socialist motherland since the 1950s. Even those Hong Kong Chinese who collaborated with the British were all inherently patriotic because of familial ties to mainland China dating back generations (Jiang 2008: 142-45). The most important task then is to help Hong Kong Chinese rediscover their latent patriotism. Jiang stipulates that the British were shrewd at “winning the hearts and minds” of Hong Kong people during their colonial rule, and Beijing should learn from the British experience. It is noteworthy that Jiang translated “winning hearts and minds” into “xinao yingxin,” which literally means “washing the brain and winning the hearts,” deviating from its original English meaning (Jiang 2008: 31). Jiang’s thesis is tantamount to saying that all Hong Kong Chinese are inherently Chinese “patriots-in-themselves” waiting to be transformed by the vanguard patriots in Beijing into “patriots-for-themselves.” It suggests that Beijing’s ideological work in Hong Kong is essential to overcoming local identities. In retrospect, Jiang’s diagnosis coincides well with Beijing’s agenda for Hong Kong in the wake of his tenure there, as shown by the 2012 attempt to introduce the compulsory National Education curriculum in all schools.

Jiang argues that the “one country, two systems” arrangement in Hong Kong, whose origins can be traced to the “Seventeen Point Agreement” between Beijing and the Dalai Lama government over Tibet in 1951, is significant not only because it anticipates Hong Kong’s reunion with China, but also because it presages the revival of China as an empire (Jiang 2008: 123-58).6 To Jiang, the Chinese empire, which reached its pinnacle in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), was grounded on the radiation of Confucian civilization and successive incorporation and transformation of its peripheral zones into its core territory. The Qing emperor allowed local elites in newly incorporated regions with distinct customs and leadership to exercise local autonomy. But not indefinitely. Over time, they would be integrated into the core territory of the empire, being culturally assimilated and having their local autonomy abolished. Then the empire would move on to incorporate other new territories. The PRC’s incorporation of Hong Kong, as well as the prospective assimilation of Hong Kong and eventual incorporation and assimilation of Taiwan, are illustrative of a similar Chinese imperial expansionist mentalité in the twenty-first century. Jiang’s implication is clear. The “one country, two systems” formula for Hong Kong is just a tactical and transitional arrangement. What awaits Hong Kong is what Tibet has seen since 1959: forced assimilation and tight direct control by Beijing.

Throughout the book, Jiang does not shy from using the term “empire” with positive connotation. He even stipulates that the revived Chinese empire should learn from the arts of rulership of the British empire. Jiang’s embrace of Maoism, quasi-fascism, and imperialism in his discussion of Hong Kong is not exceptional, but is emblematic of the CCP’s increasingly assertiveness toward Hong Kong.

Seeing Hong Kong like a PRC Liberal

Chan Koonchung’s Zhongguo tianchao zhuyi yu Xianggang is an explicit response to Jiang’s views on Hong Kong. Besides outlining an alternative interpretation of Hong Kong’s history and its historical relationship with China, Chan devotes about half of its pages to critiquing Jiang’s views. Chan rightly observes that Jiang’s views have been circulating among Chinese officials for years, but were never publicly formulated. He welcomes Jiang’s open elaboration of such views, as it offers a good opportunity to interrogate the theoretical underpinnings of China’s Hong Kong policy.

Chan himself has been an iconic cultural critic in the baby boomer generation in Hong Kong. Born in Shanghai, educated in Hong Kong, he founded the long running avant-garde City Magazine (hao wai) in 1976 that addresses cultural issues in Hong Kong. Ten years ago, he left Hong Kong and moved to Beijing where he engaged in the debate about liberalism and political reform in China. Politically his views are in line with those of mainstream moderate democrats in Hong Kong, advocating gradual democratic reform within the limits set by Beijing. Chan’s critique of Jiang is as much from a Chinese liberal perspective as from a Hong Kong perspective. He views Jiang’s embrace of the Cultural Revolution as an instance of “Great Democracy,” his Schmittian view of politics, and his open advocacy of a Chinese empire disturbing, as embodying a fascist tendency in Jiang and his intellectual companions among the New Left, or what Chan calls “right-wing Maoists” (Chan 2012: 118-22). Chan pinpoints the ways in which Jiang misreads and distorts Hong Kong’s history. To Chan, Jiang’s portrayal of the Hong Kong Chinese population’s warm reception of the PRC in the 1950s and the 1960s is pure fabrication. In fact, mainland Chinese migrants who constituted the majority of the Hong Kong population in the postwar years were those who fled Communist rule. Hong Kong people’s memories of their compatriots’ flight to Hong Kong during the Great Leap famine and the Cultural Revolution were so vivid that they could not be natural lovers of the PRC (Chan 2012: 7-10; 58-61).

Hong Kong is not a mere passive onlooker of China’s cultural and political development, but is an active participant in it, Chan points out. Besides the critique of Jiang, Chan outlines Hong Kong’s contribution to China’s liberal and constitutionalist reform from the nineteenth century to today. In the late nineteenth century, Wang Tao (1828-1897), a Chinese intellectual who founded an influential Chinese newspaper, the Universal Circulating Herald, in Hong Kong, fostered the rise of reformist thought among Chinese literati in Hong Kong and mainland China, directly fueling the late nineteenth-century constitutional monarchist reform movement led by Kang Youwei, who himself traveled to Hong Kong and was attracted by what he saw as the rational and effective governance by the British colonial authority. After the failure of the reform movement in 1898, Hong Kong became a key refuge for revolutionaries, many of whom, including the father of the Chinese republic Dr. Sun Yat-sen, had been educated in Hong Kong and exposed to European revolutionary theories there (Chan 2012: 14-21).

|

Statue of Sun Yat-sen at Sun Yat-sen Museum in Hong Kong |

Successive generations of CCP leaders recognized the utility of keeping Hong Kong separate from China. The CCP adopted a policy of not taking Hong Kong from Britain as early as 1946, recognizing that a future socialist China would need Hong Kong as a window to the world and a diplomatic link to the British. (Chan 2012: 42-46) The CCP even helped maintain the stability and viability of Hong Kong in the Mao period through provision of food and water to the British colony. Chan refers to Mao’s assertion that such a policy would tilt Britain toward China, hence weakening the Britain-US alliance that was encircling China during the Cold War. Hong Kong also offered the Chinese government a channel to absorb foreign currencies and information about the world. The significance of Hong Kong to China during the Mao era, on top of Hong Kong people’s aversion to the CCP, is the cold reality that Jiang fails to grasp or refuses to acknowledge (Chan 2012: 42-61).

Deng Xiaoping’s adoption of the “one country, two systems” model to resolve the Hong Kong question was an attempt to prolong the special role of Hong Kong within Chinese development beyond the sovereignty handover.

To Chan, such an arrangement had an unintended consequence for China’s political reform. The “one-country, two systems” formula, as set out in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, was the first instance of genuine constitutionalism and rule of law on Chinese soil. The constitutionalist implications of the Hong Kong experiment have to be defended, and Jiang’s neo-imperial theory denigrating the constitutionalist character of the “one country, two systems” arrangement as pragmatic and temporary has to be resisted. The defense of Hong Kong’s autonomy, in Chan’s eyes, is one battlefield in the larger struggle between liberal and conservative statists in China.

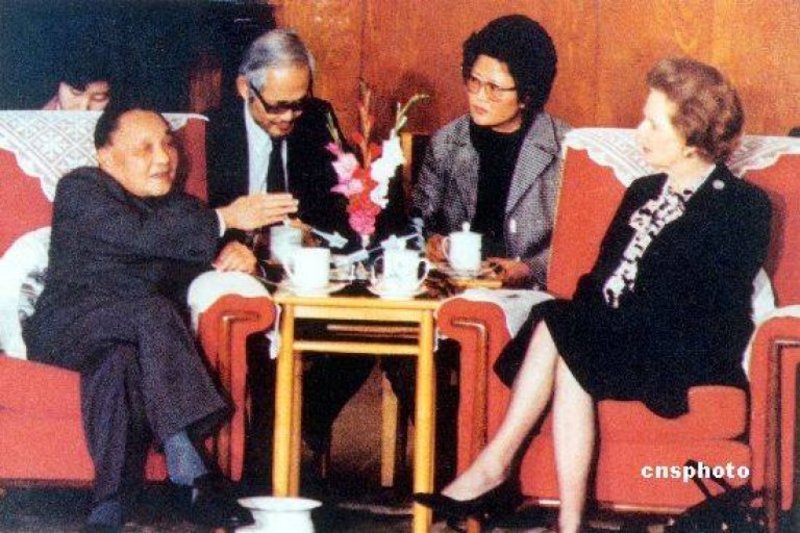

|

Deng Xiaoping expounds One Country, Two Systems to Margaret Thatcher in 1984. |

As for Hong Kong’s economic value for China after 1997, Chan concurs with the mainstream account promoted by Beijing that Hong Kong is losing its competitive edge to other Chinese cities. He reiterates the official suggestion that Hong Kong should deepen its integration with the rest of China, and be included in the central government’s five-year plans, in order to avoid economic marginalization. (Chan 2012: 70-77) Despite Hong Kong’s loss of economic distinctiveness, Chan still thinks that Beijing would not lightly destroy Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” model, arguing that the central government does not easily abandon favorable policies even toward backward cities and provinces in the mainland. But Chan also warns that Hong Kong people should be realistic and not under-estimate Beijing’s iron determination regarding its sovereignty over Hong Kong. Hong Kong people, when defending their rights and autonomy, should therefore be very careful not to transgress the limited space defined by Beijing. (Chan 2012: 70-82)

Chan’s defense of Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” model as a defense of the liberal embrace of constitutionalism against the statist onslaught should resonate well with liberal intellectuals in the PRC. But some of his arguments also manifest contradictions and do not stand up to the test of reality. Chan asserts that Jiang’s position that denigrates “one country, two systems” as a contingency plan, to be obliterated once the new Chinese empire has expanded, is gaining ground in Beijing. This means that the boundaries of Hong Kong autonomy originally set by Beijing over Hong Kong are narrowing as a result of Beijing’s increasing direct intervention into Hong Kong’s elections, media, and academia in recent years. If so, could Hong Kong people continue to defend their autonomy and seek democracy by humbly staying within the ever shrinking space offered by China?

Despite its narrowing space, we can see that such boundaries are not as iron-clad as Chan warns. Beijing remains reluctant to impose overt repression on Hong Kong, even as Hong Kong people explicitly defy the framework of the Basic Law. One example is the Article 23 anti-subversion legislation, which Hong Kong is constitutionally obligated to implement under the Basic Law. After the mass protest of 2003, Beijing allowed the Hong Kong government to shelve the legislation indefinitely. Did such resistance constitute a breach of Beijing’s rigid boundary set for Hong Kong? If so, how would Chan explain the fact that Beijing has tolerated such a breach despite his bleak warning about Beijing’s rigidity? Unfortunately, discussion of the anti-Article 23 legislation, as well as that of Hong Kong’s participation in China’s democratic movement in 1989, is missing in the book. Another example, which transpired after the book’s publication, is the successful mass resistance against Beijing’s attempted imposition of the National Education curriculum in 2012. Before the protests gained traction, mainstream democrats had been echoing Chan’s sentiments to persuade Hong Kong people not to oppose the National Education curriculum and concentrate on improving it after accepting it.

The fact that Beijing continues to tolerate the indefinite suspension of Article 23 legislation indicates that Hong Kong’s autonomy and the “one country, two systems” still perform some irreplaceable function for the CCP, contrary to Chan’s assertion of Hong Kong’s downgrading to the status of an ordinary Chinese city. In fact, analysis from China’s financial sector concurs in recognizing the unique role of Hong Kong in helping China overcome its dependence on the US dollar through RMB internationalization. To internationalize the RMB, which is increasingly powerful but not yet fully convertible, China will need an offshore market for the currency just as the US needed London’s Eurodollar market in its internationalization and rise to dominance in the 1950s. China Finance 40 Forum, a Chinese think tank organization comprised of retired financial officials and analysts from major Chinese and international financial firms, recently published a report illustrating that only Hong Kong, given its rule of law, freedom of information, and constitutional separation from China, could serve as a wholesale offshore RMB market.7 (Ma and Xu 2012).

The talk of Hong Kong becoming an ordinary Chinese city, out-performed by Shanghai and others, is little more than politically-motivated rhetoric that has been repeatedly disproved by empirical evidence and the pronounced need of Beijing to use Hong Kong’s as an offshore center facilitating capitalization of state-owned enterprises and RMB internationalization.8 While Chan’s critique of Jiang’s imperial discourse is powerful, his suggestion about how Hong Kong people should resist the Chinese imperium is premised on uncritical acceptance of such rhetoric.

Seeing Hong Kong like a Hong Konger

If Chan’s book is a critique of Jiang’s discourse based on emphasizing the utility of Hong Kong’s autonomy to China’s constitutionalist reform, Chin Wan’s On the Hong Kong City-State responds to Jiang by highlighting the significance of Hong Kong autonomy for the sake of Hong Kongers. The book triggered fierce public debate and was hugely popular. It was selected as one of the best books of the year in 2011 by the Hong Kong Book Prize organized by Radio and Television Hong Kong, and has been on the bestseller list of all major bookstore chains ever since its publication in late 2011. The author Chin Wan (real name Chin Wan-kan), a PhD in ethnology from the University of Gottingen and a senior advisor to the HKSAR government on cultural, arts, and civic affairs from 1997 to 2007, rose to become a leading critical intellectual voice against the destruction of local communities and historical edifices amidst the craze of urban redevelopment. Using the pen name Chin Wan, he devoted many of his newspaper columns to supporting the young radicals who became increasingly militant in opposing Hong Kong and Chinese real estate tycoons and Beijing’s intervention in Hong Kong.

One important starting point for Chin’s view is that China needs Hong Kong more than Hong Kong needs China, and that this was as true in the past as it is at present. The conception that Hong Kong was one-sidedly reliant on China for essential foodstuffs in colonial times and for capital and consumers in postcolonial times is shown to be propaganda devised by Beijing to destroy the self-confidence of the Hong Kong people. Chinese supply of foodstuffs and water to colonial Hong Kong, before the 1980s was one of the few channels through which China could absorb foreign currency in the face of US blockade. Hong Kong’s purchase of Chinese water supply has been much more expensive than sea water desalination, a technology that Singapore relies on for its water. China’s reliance on Hong Kong investment throughout the period of market transition and internationalization of the economy is well known. As of 2012, investment from Hong Kong still made up a staggering 64 percent of all foreign direct investment inflow into China. (Chin 2011: 112-127; 135-140)

Though Hong Kong had been a British colony before 1997, the Hong Kong government, in alliance with local British and Chinese capitalist interests, in fact enjoyed substantial autonomy from London, making Hong Kong a de facto city-state.9 Chin finds that Beijing tried its best to maintain the city-state character of Hong Kong in the years 1997-2003, restraining itself from excessive intervention. But with the failure of Article 23 legislation, Beijing radically changed its Hong Kong strategy. Beijing still could not resort to outright crackdown, but it started trying to dissolve the city-state boundary of Hong Kong in the name of economic rejuvenation and Hong Kong-China socio-economic integration. (Chin 2011: 145-63)

One key policy under this initiative is to open the floodgates for mainland tourists to Hong Kong. Mainland visitors to Hong Kong multiplied and as of 2012, the annual count of mainland visitors reached 35 million, five times Hong Kong’s total population of about 7 million. The Hong Kong government has no authority to reject or restrict mainland tourists on Hong Kong passes issued by the Chinese government. The sudden surge in mainland tourists generated escalating conflict and tension between Hong Kong residents and mainlanders, when shops for luxury goods and daily necessities alike started to prioritize mainland tourists customers, who are willing to pay more for goods that are usually unavailable or available at much higher prices (because of import tariffs) in the mainland. Smuggling milk formula into China also became a significant sideline business of many mainland visitors in the wake of the mainland’s tainted milk scandal in 2008, emptying the shelves of groceries and pharmacies in some districts in Hong Kong. The difference in social customs (with isolated but much-publicized events of queue jumping, or defecating in public space, etc) distinguishing locals from mainlanders became contentious.

Local CCP organizations also escalated efforts to organize recent mainland migrants – who are unilaterally granted “one-way visas” to Hong Kong by the Chinese government (officially for family reunion purposes) at a rate of 150 per day without prior screening by the Hong Kong government – into loyal voting blocs. New mainland immigrants who moved to Hong Kong between 1997 and 2012 now constitute about 10 percent of Hong Kong’s total population. Journalist Ching Cheong, formerly an editor at the pro-Beijing Wen Wei Po, wrote that the CCP has been using such migration schemes to send its agents into different strata of Hong Kong society, and that the remaining quotas are often sold by corrupt mainland officials.10 Long-term opposition leader Martin Lee sees such migration policies to turn Hong Kong’s original residents, who grew up in Hong Kong and identify with Hong Kong’s core values into a minority, in the long run as a Tibetization of Hong Kong.11 Donald Tsang, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong from 2005 to 2012, and his think tank organization were not shy about openly suggesting that Hong Kong needed a “population blood transfusion,” replacing locals with mainland migrants. It has been reported widely that the CCP (which has no legal existence in Hong Kong) has been quite successful in guaranteeing new immigrant votes for its favored candidates via vote buying and other legal or illegal electoral maneuvers.

Chin asserts that the influx of mainland tourists and migrants poses the largest threat to the established institutions and social customs of Hong Kong. He therefore advocates that Hong Kong government should take back the authority to screen incoming migrants from mainland China, just as it does for migrants from all other countries and as all other governments in the world would do. The number of incoming mainland tourists must be reduced in his view. But to Chin’s disappointment, the Hong Kong opposition movement has never taken these issues seriously. On the contrary, they have labeled complaints about mainland tourists and Hong Kong’s lack of authority to screen mainland migrants as “xenophobic,” even though without screening authority, Hong Kong’s situation is more akin to settler colonization by the mainland. (Chin 2011: 150-63)

Chin attributes the Hong Kong opposition’s reluctance to defend the Hong Kong-China boundary to their Chinese nationalist ideology. For many generations, democrats in Hong Kong have dreamed of a liberal and democratic China. To them, the democratic movement in Hong Kong is subsidiary to that in China. This makes them inadvertent supporters of Beijing’s scheme to colonize Hong Kong (Chin 2011: 175-79; 51-54). In reaction to this prioritization of mainland China over Hong Kong among the democrats, Chin put forward the most controversial thesis in his book, that is, democratization in China is hopeless; if democratization really comes to China, it will only bring fascism and hurt Hong Kong (Chin 2011: 36-56).

Chin’s gloomy view of the prospect of China’s democratization is grounded on the observation that after more than sixty years of Communist rule, and the last thirty years of unfettered capitalist boom, both the big and little traditions that formerly held Chinese society together and fostered trust among its people have been annihilated. Once the authoritarian state crumbles, the atomized society that remains will not be able to foster healthy democratic institutions, at least not in the immediate aftermath of such a collapse. That would be a seedbed for the rise of outright fascist politics. Chin therefore advocates “Hong Kong First” and “Hong Kong-China separation” positions in lieu of the “China First” and “China-Hong Kong integration” advanced by mainstream democrats. To Chin, fighting China’s neo-imperial approach to Hong Kong and rejecting the PRC liberals’ subordination of Hong Kong’s opposition movement to their larger struggle for China’s democratization are equally important in defending and advancing Hong Kong’s city-state-like autonomy, without which Hong Kong can never be genuinely democratic.

Three Books and Three Futures of Hong Kong

Wars of ideas are never without correspondence with political struggles on the ground. The competing views of Jiang Shigong, Chan Koonchung, and Chin Wan respectively represent the respective lines of (1) Beijing, which is impatient to assimilate Hong Kong and impose mainland techniques of exercising power on the territory, (2) mainstream Hong Kong democrats who pin their hopes not on the struggle of Hong Kong people but on China’s elusive democratic reform, and (3) budding local autonomy movements, which are prepared to defy Beijing and promote Hong Kong democracy.

While Beijing has been increasingly aggressive in tightening its reign on Hong Kong, mainstream democrats, as well as their older propertied middle class social base, have been ever more timid, despite holding most of the directly elected Legislative Council seats and enjoying the support of mainstream media. Youthful localist movements, still divided and marginal, but popular among the younger generation coming of age after 1997, have attained successes, such as forestalling the National Education curriculum and forcing the government to crack down on milk formula smuggling and birth tourism, with little support from mainstream democrats.

|

September 2014 student-led protest in Hong Kong |

In 2014, Hong Kong citizens are again in the streets, en masse. The future of Hong Kong will hinge on the interplay of the above three forces. How they will play out is still too early to tell. But by comparing the popularity of the three books, it is apparent that the localist view is on the rise. This is not surprising, given that liberals in the PRC have been confronting setback after setback, and that opinion polls consistently reveal a surge in localist Hong Kong identity that no mainstream political forces have yet understood or managed to muster. Whether such Hong Kong localism will continue to rise, reaching the level of Taiwan nationalism and fueling and sustaining a more militant opposition movement, remains to be seen.

Ho-fung Hung is Associate Professor of Sociology, Johns Hopkins University specializing in global political economy, protest, nation-state formation, and social theory, with a focus on East Asia. He is the author of Protest with Chinese Characteristics: Demonstrations, Riots, and Petitions in the Mid-Qing Dynasty and the editor of China and the Transformation of Global Capitalism.

Recommended citation: Ho-fung Hung, “Three Views of Consciousness in Hong Kong”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 44, No. 1, November 3, 2014.

Notes

1 This is a revised version of a French version of a text that was published as “Trois visions de la conscience autochtone à Hong Kong” in Critique n° 807-808 Août-Septembre 2014, on the eve of the outbreak of the Umbrella Revolution in late September.

2 The Hong Kong government’s proposed law stated that “The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organizations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.” The legislation was suspended.

3 Past and Present 50 (1) 1971, 71-136.

4 People’s Ethnic Identity survey, Public Opinion Program, University of Hong Kong.

5 Lilla, Mark. 2010. “Reading Strauss in Beijing” The New Republic. December 10, 2010;

Ma Jun and Xu Jianjiang, Renminbi zhouchu guomen zhi lu: li’an shichang fazhan yu ziben xiangmu kaifang (Pathway for Renminbi internationalization: development of offshore markets and capital account liberalization). Hong Kong: Commercial Press.

6 The complete text of the 1951 agreement in Chinese, Tibetan and English is available.

7 Ma Jun and Xu Jianjiang 2012. Pathway for Renminbi internationalization.

8 See “Why Hong Kong remains vital to China’s economy” The Economist September 30, 2014 for example.

9 Yep, Ray 2013. Negotiating Autonomy in Greater China: Hong Kong and its Sovereign Before and After 1997. Copenhagen, Denmark: NIAS Press.

10 Ching Cheong 2012. “Cong shiba da kan Xianggang dixia dang guimo” (Assessing the size of underground CCP organizations in Hong Kong from the perspective of the 18th Party Congress) Mingpao November 7, 2012.

11 Lee, Martin 2012. “Xianggang Xizang hua” (Tibetization of Hong Kong) Next Magazine. September 29, 2012.