On the 110th anniversary of the death of Lafcadio Hearn, Roger Pulvers examines the legacy—for Japan and the United States—of Japan’s most famous gaijin.

A small cage was opened at Lafcadio Hearn’s funeral, setting birds into the air, the soul of the deceased presumably taking flight with them. His coffin was draped in chrysanthemums and fragrant olive, adorned by a laurel wreath. Seven Buddhist priests read the sutras at Kobudera (now Jishoin Enyuji Temple) in Shinjuku Ward’s Ichigaya-Tomihisacho district in Tokyo, where Hearn had frequently strolled among the gravestones.

The non-Japanese community was vehemently put off by the choice of venue. As if the officiation of the Buddhist priests wasn’t insult enough, they were enraged by the Occidental’s profane choice of a temple for the funeral.

Hearn himself had been a living outrage to the non-Japanese community, a role that he, as an anti-Christian and anti-imperialist, had thoroughly relished. Only three foreigners attended the ceremony.

Forty Japanese professors and about 100 students from the two universities at which he had taught — Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) and Waseda University — were also in attendance. However, this gives the wrong impression of his popularity among the Japanese population at the time. In his day Hearn was a virtual unknown in his adopted country. It was outside Japan that he was widely admired as the premier interpreter of the ways of the Japanese, seen ruefully by those in the West and often proudly by the Japanese themselves as far and away the world’s most inscrutable people.

In the short period of 14 years that he had lived in Japan, he felt that he had become privy to the most deeply cherished secrets of the Japanese mindset. His obituary appeared in a host of American newspapers. On Nov. 26, 1904, two months to the day after his death, The Oregon Journal wrote of him as the “Poet of Japan — he had become Japanese Thru and Tru, tried to hide himself from foreigners and to bind himself closer and closer to his chosen country.”

Author and poet Noguchi Yone (father of U.S. sculptor Isamu Noguchi) called Hearn “a delicate, easily broken Japanese vase.”

The pivotal word here is “Japanese,” for Lafcadio Hearn, born smack in the middle of the 19th century as the son of a Greek mother and an Irish father, had naturalized as a Japanese, taking on the name Koizumi Yakumo six years after arriving in Japan. In his writings he extolled as unique and exquisite every feature of the old Japanese character and folk culture, cheerfully alienating himself from white Christian society in Japan. He recreated a Japan that was receding into the shadows — for he had always preferred shadows to light — and plunged into them, wallowing in the illusion that this alone was the “real” Japan.

This all gave rise to a fascinating paradox: the subsequent crisscrossing of his reputation. In the years succeeding his death, his reputation in the West went into a gradual but certain decline. On Sept. 19, 1904, a week before Hearn’s death, Japanese troops under the command of Gen. Nogi Maresuke attacked the Russians at Port Arthur, the strategic outpost at Lushun Port in China. Hearn was not to see Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War the next year, but that victory set Japan on a course of chauvinistic conquest that poured adrenalin into veins already streaming with national pride. It was then, as Hearn was being increasingly seen in the West as an apologist for the “Oriental upstart” — which he most definitely was not — that the Japanese adopted their not-so-native son as a spokesman. Here it was – written in English by a non-Japanese – proof that the Japanese soul was more profound, more subtle and more potent in its pure spirituality than anything the materialistic West could possibly muster. They saw in him someone who had come to Japan without a hidden Western agenda, which was true. They also saw someone who loved Japan unequivocally, which was definitely not true. (Since then they have conveniently ignored his unequivocal and vigorously anti-Japanese side.)

Hearn had been an orphan of Europe, a rootless cosmopolitan and wanderer seemingly at home nowhere but in Japan. Now he was being brandished by the Japanese, their sharpened sword, as witness to the superiority of their national character over people in Western and other Asian nations.

How did a misfit who found neither lasting companionship nor solace in Europe and the United States come to be a shining symbol for the Japanese of their self-styled superiority?

The odds had been against him all his life.

His parents took him from his mother’s homeland in the Ionian Islands of Greece, then a British Army protectorate, to his father’s home in Dublin when he was just 2 years old. It was not an uncommon type of liaison. Charles Bush Hearn, dashing staff surgeon in the British Army, had encountered local beauty Rosa Kassimati at a dance. She was illiterate, though of good family. A son was born; and when Rosa was pregnant with Lafcadio, the couple decided to marry. The first son passed away shortly after Lafcadio’s birth on June 27, 1850. Later Charles was able to have the marriage annulled because Rosa had been unable to sign the certificate.

When Lafcadio and his mother reached Dublin in 1852 they would have seen a city ravaged by destitution and overpopulation at the end of the Great Famine. While Ireland had lost up to a quarter of its population through death and emigration, the population of the capital had swelled. Mother and son were fortunate. They were put under the care of Charles’ aunt, Sarah Brenane, a martinet of piety living in the well-to-do district of Rathmines. (The house today bears a plaque commemorating Hearn’s years there.)

Rosa, who became pregnant once more after a short visit by her husband, abandoned Lafcadio and Dublin in 1854. (Charles re-encountered an old sweetheart, Alicia Crawford, on this visit and eventually married her.) How could a woman born and raised on the Greek isles cope with the gray misery of the Dublin climate and the strict domestic practices of a household whose language she did not understand? Lafcadio was never to see his mother again, and had only brief and deeply unsatisfactory encounters with his father. He never met his younger brother, James (who passed away in St. Louis in 1933, 29 years after Lafcadio’s death), though both of them, by chance, ended up living in the state of Ohio at the same time; and felt, until he arrived in Japan in 1890, that the fetters of family were something he would not encumber himself with in his wildest dreams.

But it was with just such a family that Hearn found himself fettered late in his life. This Poe-faced outsider and aficionado of the eerie and the bizarre, who any number of times had been bereft of the barest means of subsistence, living off the smell of an oily rag in London, sleeping rough and wandering the streets of the Rue Morgue in Cincinnati and New Orleans, was to be earning a formidable salary as a teacher in Japan while supporting up to 11 people, including wife, four children, in-laws and servants. He published on average a book for every year he lived in Japan and was read eagerly not only by Americans for his esoteric insights into Japanese mores, traditions and passing lifestyle, but also by readers in China, India and Europe, though not Japan.

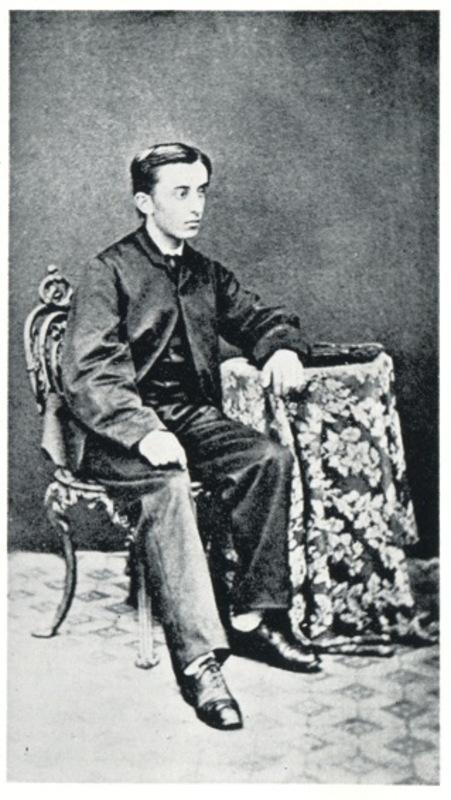

|

Hearn at 16 |

After being sent out of his great-aunt’s home and packed off, at age 19, to the United States, he travelled to Cincinnati, where he landed a job as a reporter at the city’s leading newspaper. His output was prodigious. His articles, largely dealing with serious crime and full of gruesome detail, were devoured by readers. However, his marriage to a black woman in June 1874 caused an outrage, and he was sacked from his job. The woman, Alethea Foley, was, like Hearn’s mother, illiterate; and, like his parents’ marriage, his was not considered valid. Ohio law at the time prohibited marriages of mixed race.

Hearn left Cincinnati and drifted to New Orleans, where once again he became a popular reporter. After spending two years on Martinique, West Indies, he returned to the United States, although the prospects for his employment were meager. And then Lady Luck smiled on him in the form of an invitation to go to Japan and write up his impressions for Harper’s Magazine. The American public was crying out for information about the country that had emerged from the obscurity of isolation and was intriguing the world with its mysterious culture. Hearn crossed Canada by train, embarked from Vancouver and arrived at Yokohama on April 4, 1890, age 39.

Through the good offices of professor Basil Hall Chamberlain of Tokyo Imperial University, he was offered a job teaching at the Ordinary Middle School in the old castle town of Matsue on the coast of the Sea of Japan. There he met Koizumi Setsu, nearly 18 years his junior. Setsu had been married and divorced, which made her highly ineligible for another union to a Japanese. Of course, no one would have imagined that an eligible foreigner would come to live in Matsue. But such an eccentric one did and in January 1891, the two were married.

The Hearns moved to Kumamoto in Kyushu — where for three years he developed a particular contempt for the city, writing, “(Kumamoto is) my realization of a prison in the bottom of hell” — and then on to Kobe, where once again he practiced his old profession of journalism. Severe eyesight problems prevented him from continuing, and before long he found himself on the teacher’s podium, this time at Tokyo Imperial University. He longed to leave Japan, but illness and lack of opportunity prevented it.

Hearn became known again in the West after World War II, when Americans in particular craved exotic detail about their new friends in the Far East. As Japan coursed ever further from the vanishing world that he had depicted, Hearn’s adulatory image of the country suited Japanese needs once again, this time to reassure them that they had the spiritual backbone to withstand the heavy weight of American “values” lowered, willy nilly, on their shoulders.

Hearn may have been a story-reteller of great perspicacity, but his prose is rich in the florid cliches of the Victorian era and all too often bogged down by a stilted lyricism. It is fortunate for his reputation among the Japanese that this flowery language translates well into Japanese.

|

Hearn and his wife Setsu |

His true genius, however, lies in the brilliant clarity and careful detail of his reportage. He is, I believe, America’s foremost documentarian of American life in the last half of the nineteenth century. If you want to experience his best writing, read the hundreds of articles he wrote about America’s subculture during his years in the country. He does not shirk from any detail, however morbid or distasteful. He flaunts the decoy that is decorum. He does accurate fieldwork like a present-day anthropologist. He not only visits but throws himself into places where others fear to go: the morgues, the dens of crime, the slaughterhouses, the dangerous haunts of every pariah on every skid row in town — and always with an empathetic outlook on the misery of the people and even the animals caught up there. He writes with great sympathy about all aspects of black culture, from the argot of the roustabouts on the Cincinnati docks to the practitioners of Creole folk medicine in New Orleans (“for tetanus, cockroach tea is given; a poultice of boiled cockroaches is placed over the wound”). There is not a drop of racist blood in Hearn’s body. In the day of post-bellum America, where white brutality against blacks was vicious, arbitrary and unrelenting, Hearn embraced and extolled black subculture.

As a journalist, Hearn had an indefatigable curiosity and chutzpa to match. In May 1876 he asked to be hoisted up the spire of Cincinnati’s tallest structure, the Cathedral of St. Peter-in-Chains, describing the city from there though petrified with fear. He later wrote to his friend, the musicologist Henry Krehbiel, of the intense delight he felt “piddling on the universe.”

Had he lived another two or three decades, he would have been appalled at the manner in which the self-aggrandizing powerbrokers in the cultural establishment of Japan used him for the purposes of justifying incursions into Asia. He loathed the modern Japanese male and what he stood for, and in this he recognized the futility of his task, a futility keenly felt toward the end of his years, where he heard “nothing but soldiers and the noise of bugles.”

|

Hearn’s photograph of Martinique |

He worshipped the static and wanted to see his beloved quaint Japan remain as sweet as it always was in his eye and the eyes of the world, bemoaning all progress: “What, what can come out of all this artificial fluidity!”

He was the shadow-maker, the illusionist who conjured up his own visions of Japan and gladly lost himself in them. He strove to leave Japan and return to the United States. Perhaps he realized that it was there that he had created his most accomplished work, attaining something he savored: notoriety. Again an ironical paradox emerges. He is remembered now in United States, if at all, not for his superb reportage on modern America but for his adoration of a long-gone Japan.

There was a chance to get back to America when Jacob Gould Schurman, president of Cornell University, agreed at the end of 1902 to invite Hearn to present a series of lectures. The proposal never materialized into an invitation. This may have been due to an outbreak of typhoid fever on campus, causing him to be wary of visitors from Asia, although it is much more likely that Schurman was more wary of Hearn’s notorious cantankerousness than of unwanted Eastern maladies. At any rate, the proposal was withdrawn in March 1903.

|

Hearn, wife Setsu and son Kazuo |

The cruelties of Hearn’s childhood had made him painfully shy of any lasting relationship. Yet he was uncannily caring of his eldest son, Kazuo, and of his wife, Setsu, whom he called “Lovely Little Mama Sama,” writing to her from the seaside just a month before he died.

“I feel lonely sometimes; I wish I could see your sweet face. I beseech you that you will take care of your own self. … You must never think of any danger which might occur to your boy.”

He signed those letters with his Japanese name, Koizumi Yakumo.

Koizumi Yakumo, also known as Lafcadio Hearn, is buried beside Setsu and Kazuo in the Zoshigaya Cemetary in Tokyo.

From the letters and writings of Lafcadio Hearn

“What the finer nature of the Japanese woman is, no man has told. It would be too much like writing of the sweetness of one’s own sister or mother. One must leave it in sacred silence with a prayer to all the gods.”

“What is our individuality? Most certainly it is not individuality at all. It is multiplicity incalculable…. What being ever had a totally new feeling, an absolutely new idea? All our emotions and thoughts and wishes … are only compositions and recompositions of the sensations and ideas and desires of other folk, mostly of dead people….”

“Christianity, while professing to be a religion of love, has always seemed to me in history and practice to be a religion of hate….”

“Buddhism makes an appeal to the human heart, and Shinto only to traditional and race feelings.”

“(Japan) is certainly going to lose all its charm, all its Japaneseness; it is going to become all industrially vulgar….”

“I think a man must devote himself to one thing in order to succeed, so I have pledged (myself) to the worship of the Odd, the Queer, the Strange, the Exotic, the Monstrous.”

“I must be able to travel again some day, to alternate Oriental life with something else.”

“In the boom of the big bell there is a tone which wakens feelings so strangely far away from the nineteenth-century part of me that the faint blind stirrings of them make me afraid.”

“The delicate souls pass away; the rough stay on and triumph.”

Roger Pulvers is the author of more than 40 books in Japanese and English. His novel “The Dream of Lafcadio Hearn” is published by Kurodahan Press.

This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in The Japan Times on September 21, 2014.

Recommended citation: Roger Pulvers, “The Life and Death of Lafcadio Hearn: A 110-year perspective,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 38, No. 4, September 22, 2014.