Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: “In God is our trust.”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

I. US Firebombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan

This paper assesses and compares the impact and historical significance of the firebombing and atomic bombing of Japanese cities in the history of war and the history of disaster. Japan’s decision to surrender, pivoting on issues of firebombing and atomic bombing, Soviet entry into the war, and the origins of Soviet-American confrontation, is the most fiercely debated subject in twentieth century American global history. The surrender question, however, is addressed only in passing here. The focus is rather on the human and social consequences of the bombings, and their legacy in the history of warfare and historical memory in the long twentieth century. Part one provides an overview of the calculus that culminated in the final year of the war in a US strategy centered on the bombing of civilians and assesses its impact in shaping the global order. Part two examines the bombing in Japanese and American historical memory including history, literature, commemoration and education. What explains the power of the designation of the postwar as the atomic era while the area bombing of civilians by fire and napalm, which would so profoundly shape the future of warfare in general, American wars in particular, faded to virtual invisibility in Japanese, American and global consciousness?

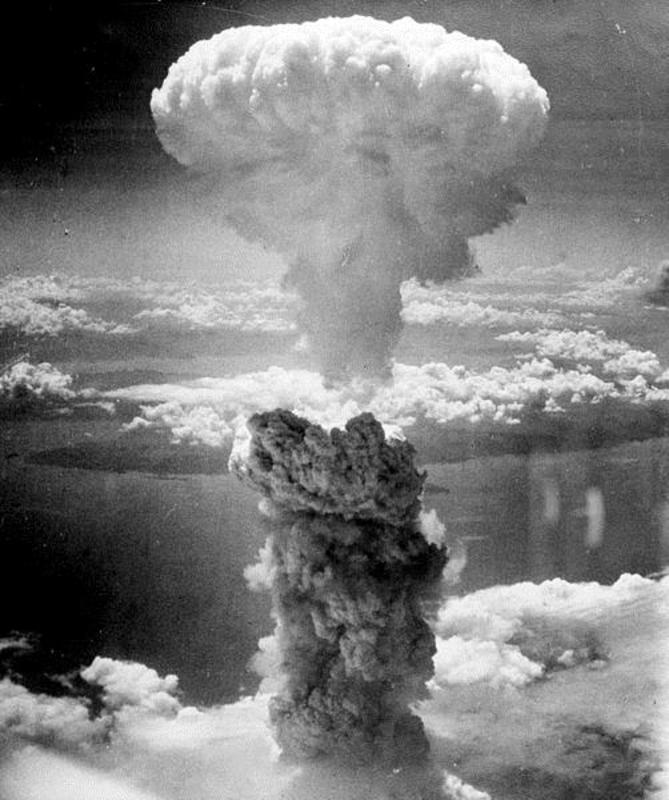

World War II was a landmark in the development and deployment of technologies of mass destruction associated with air power, notably the B-29 bomber, napalm, fire bombing, and the atomic bomb. In Japan, the US air war reached peak intensity with area bombing and climaxed with the atomic bombing of Japanese cities between the night of March 9-10 and the August 15, 1945 surrender.

The strategic and ethical implications and human consequences of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have generated a vast, contentious literature. By contrast, the US destruction of more than sixty Japanese cities prior to Hiroshima has been slighted, at least until recently, both in the scholarly literatures in English and Japanese and in popular consciousness. It has been overshadowed by the atomic bombing and by heroic narratives of American conduct in the “Good War” that has been at the center of American national consciousness thereafter.2Arguably, however, the central breakthroughs that would characterize the American way of war subsequently occurred in area bombing of noncombatants prior to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A.C. Grayling explains the different responses to firebombing and atomic bombing this way:

. . . the frisson of dread created by the thought of what atomic weaponry can do affects those who contemplate it more than those who actually suffer from it; for whether it is an atom bomb rather than tons of high explosives and incendiaries that does the damage, not a jot of suffering is added to its victims that the burned and buried, the dismembered and blinded, the dying and bereaved of Dresden or Hamburg did not feel.”3

Grayling does, however, go on to note the different experiences of survivors of the two types of bombing, particularly as a result of radiation symptoms from the atomic bomb, with added dread in the case of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki hibakusha, not only for themselves but also for future generations.

If other nations, notably Germany, England and Japan led the way in area bombing during World War II, US targeting of entire cities with conventional weapons emerged in 1944-45 on a scale that quickly dwarfed all previous destruction. Targeting for the most part then and subsequently essentially defenseless populations, it was an approach that combined technological predominance with a priority on minimization of US casualties. This would become a hallmark of the American way of war in campaigns from Korea and Indochina to the Gulf and Iraq Wars. The result would be the decimation of noncombatant populations and extraordinary “kill ratios” favoring the US military. Yet for the US, victory in subsequent wars-Korea, Indochina, Afghanistan and Iraq being the most notable-would prove extraordinarily elusive. This is one reason why, six decades on, World War II retains its aura for Americans as the “Good War”, a conception that renders difficult coming to terms with the massive bombing of civilians in the final year of the war.

As Michael Sherry and Cary Karacas have pointed out for the US and Japan respectively, prophecy preceded practice in the destruction of Japanese cities. Sherry observes that “Walt Disney imagined an orgiastic destruction of Japan by air in his 1943 animated feature Victory Through Air Power (based on Alexander P. De Seversky’s 1942 book),” while Karacas notes that the best-selling Japanese writer Unna Juzo, beginning in his early 1930s “air-defense novels”, anticipated the destruction of Tokyo by bombing.4

Curtis LeMay was appointed commander of the 21st Bomber Command in the Pacific on January 20, 1945. Capture of the Marianas, including Guam, Tinian and Saipan in summer 1944 had placed Japanese cities within effective range of the B-29 “Superfortress” bombers, while Japan’s depleted air and naval power and a blockade that cut off oil supplies left it virtually defenseless against sustained air attack.

The full fury of firebombing and napalm was unleashed on the night of March 9-10, 1945 when LeMay sent 334 B-29s low over Tokyo from the Marianas.5 Their mission was to reduce much of the city to rubble, kill its citizens, and instill terror in the survivors. Stripped of their guns to make more room for bombs, and flying at altitudes averaging 7,000 feet to evade detection, the bombers carried two kinds of incendiaries: M47s, 100-pound oil gel bombs, 182 per aircraft, each capable of starting a major fire, followed by M69s, 6-pound gelled-gasoline bombs, 1,520 per aircraft in addition to a few high explosives to deter firefighters.6 The attack on an area that the US Strategic Bombing Survey estimated to be 84.7 percent residential succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of air force planners.

Nature reinforced man’s handiwork in the form of akakaze, the red wind that swept with hurricane force across the Tokyo plain and propelled firestorms with terrifying speed and intensity. The wind drove temperatures up to eighteen hundred degrees Fahrenheit, creating superheated vapors that advanced ahead of the flames, killing or incapacitating their victims. “The mechanisms of death were so multiple and simultaneous-oxygen deficiency and carbon monoxide poisoning, radiant heat and direct flames, debris and the trampling feet of stampeding crowds-that causes of death were later hard to ascertain . . .”7

The Strategic Bombing Survey provided a technical description of the firestorm and its effects on Tokyo:

The chief characteristic of the conflagration . . . was the presence of a fire front, an extended wall of fire moving to leeward, preceded by a mass of pre-heated, turbid, burning vapors . . . . The 28-mile-per-hour wind, measured a mile from the fire, increased to an estimated 55 miles at the perimeter, and probably more within. An extended fire swept over 15 square miles in 6 hours . . . . The area of the fire was nearly 100 percent burned; no structure or its contents escaped damage.

Aerial photo of Tokyo after the bombing of March 9-10. US National Archives |

The survey concluded-plausibly, but only for events prior to August 6, 1945-that

“probably more persons lost their lives by fire at Tokyo in a 6-hour period than at any time in the history of man. People died from extreme heat, from oxygen deficiency, from carbon monoxide asphyxiation, from being trampled beneath the feet of stampeding crowds, and from drowning. The largest number of victims were the most vulnerable: women, children and the elderly.”

How many people died on the night of March 9-10 in what flight commander Gen. Thomas Power termed “the greatest single disaster incurred by any enemy in military history?” The Strategic Bombing Survey estimated that 87,793 people died in the raid, 40,918 were injured, and 1,008,005 people lost their homes. The Tokyo Fire Department estimated 97,000 killed and 125,000 wounded. According to Japanese police statistics, the 65 raids on Tokyo between December 6, 1944 and August 13, 1945 resulted in 137,582 casualties, 787,145 homes and buildings destroyed, and 2,625,279 people displaced.8 The figure of roughly 100,000 deaths, provided by Japanese and American authorities, both of whom may have had reasons of their own for minimizing the death toll, seems to me arguably low in light of population density, wind conditions, and survivors’ accounts.9 With an average of 103,000 inhabitants per square mile and peak levels as high as 135,000 per square mile, the highest density of any industrial city in the world, 15.8 square miles of Tokyo were destroyed on a night when fierce winds whipped the flames and walls of fire blocked tens of thousands who attempted to flee. An estimated 1.5 million people lived in the burned out areas. Given the near total inability to fight fires of the magnitude produced that night10, it is possible, given the interest of the authorities to minimize the scale of death and injury and the total inability of the civil defense efforts to respond usefully to the firestorm, to imagine that casualties may have been several times higher than the figures presented on both sides of the conflict. Stated differently, my view is that it is likely that the number of fatalities was substantially higher: this is an issue that merits the attention of researchers, beginning with the unpublished records of the US Strategic Bombing Survey.

The single effective Japanese government measure taken to reduce the slaughter of US bombing was the 1944 evacuation to the countryside of 400,000 third to sixth grade children from major cities, 225,000 of them from Tokyo, with 300,000 first to third graders following in early 1945.11

No previous or subsequent conventional bombing raid anywhere ever came close to generating the toll in death and destruction of the great Tokyo raid of March 9-10. Following the Tokyo raid of March 9-10, the firebombing was extended nationwide. In the ten-day period beginning on March 9, 9,373 tons of bombs destroyed 31 square miles of Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe. Overall, bombing strikes destroyed 40 percent of the 66 Japanese cities targeted, with total tonnage dropped on Japan increasing from 13,800 tons in March to 42,700 tons in July.12 If the bombing of Dresden produced a ripple of public debate in Europe, no discernible wave of revulsion, not to speak of protest, took place in the US or Europe in the wake of the far greater destruction of Japanese cities and the slaughter of civilian populations on a scale that had no parallel in the history of bombing.

Viewed from another angle, it would be worth inquiring about Japanese responses to the bombing. Japanese ideological mobilization and control was such that there are no signs of resistance to the government’s suicidal perpetuation of the war at any time during the bombing campaign. Whatever the suffering, most Japanese then and subsequently appear to have accepted the legitimacy of the decision to continue fighting a hopeless war, a theme to which I return below. Overall, by Sahr Conway-Lanz’s calculation, the US firebombing campaign destroyed 180 square miles of 67 cities, killed more than 300,000 people and injured an additional 400,000, figures that exclude the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.13 Karacas and Fisk conclude that the firebombing raids “destroyed a significant percentage of most of Japan’s cities, wiped out a quarter of all housing in the country, made nine million people homeless, and killed at least 187,000 civilians, and injured 214,000 more,” while suggesting that the actual figures are likely higher.14

Throughout the spring and summer of 1945 the US air war in Japan reached an intensity that is still perhaps unrivaled in the magnitude of human slaughter.15 That moment was a product of the combination of technological breakthroughs, American nationalism, and the erosion of moral and political scruples pertaining to the killing of civilians. The point is not to separate the United States from other participants in World War II, but to suggest that there is more common ground in the war policies of Japan and the United States in their disregard of citizen victims than is normally recognized in the annals of history and journalism.

The targeting for destruction of entire populations, whether indigenous peoples, religious infidels, or others deemed inferior, threatening or evil, may be as old as human history, but the forms it takes are as new as the latest technologies of destruction and strategic innovation, of which firebombing and nuclear weapons are particularly notable in defining the nature of war in the long twentieth century.16 The most important way in which World War II shaped the moral and technological tenor of mass destruction was the erosion in the course of war of the stigma associated with the systematic targeting of civilian populations from the air, and elimination of the constraints, which for some years had restrained certain air powers from area bombing. What was new was both the scale of killing made possible by the new technologies and the routinization of mass killing of non-combatants, or state terrorism. If area bombing remained controversial throughout much of World War II, something to be concealed or denied by its practitioners, by the end it would become the acknowledged centerpiece of war making, emblematic above all of the American way of war even as the nature of the targets and the weapons were transformed by new technologies and confronted new forms of resistance. In this I emphasize not US uniqueness but the quotidian character of targeting civilians found throughout the history of colonialism and carried to new heights by Germany, Japan, Britain and the US during and after World War II.

Concerted efforts to protect civilians from the ravages of war peaked in the late nineteenth century, with the League of Nations following World War I, and again in the aftermath of World War II with the founding of the United Nations, German and Japanese War Crimes Tribunals, and the 1949 Geneva Accords and its 1977 Protocol.17 The Nuremberg Indictment defined “crimes against humanity” as “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war,” language that could be interpreted to resonate powerfully with the area bombing campaigns conducted not only of Japan and Germany but also by Britain and the US.18 For the most part, these efforts have done little to stay the hand of power, though they have sometimes aroused public consciousness and provided a reference point for campaigns aiming to protect civilians from destruction. And while the atomic bomb would leave a deep imprint on the collective consciousness of the twentieth century, in most countries memory of the area bombings and firebombing of major cities soon disappeared from the consciousness of all but the surviving victims and their families.

The US has not unleashed an atomic bomb in the decades since the end of World War II, although it has repeatedly threatened their use in Korea, in Vietnam and elsewhere. It nevertheless incorporated annihilation of noncombatants into the bombing programs that have been integral to the successive “conventional wars” that it has waged subsequently. With area bombing at the core of its strategic agenda, US attacks on cities and noncombatants would run the gamut from firebombing, napalming, and cluster bombing to the use of chemical defoliants and depleted uranium weapons and bunker buster bombs in an ever expanding circle of destruction whose recent technological innovations center on the use of drones controlling the skies and bringing terror to inhabitants below.19

Places the United States Has Bombed, 1854-Ongoing. Artist elin o’Hara slavick21 |

Less noted then and since were the systematic barbarities perpetrated by Japanese forces against resistant villagers, though this produced the largest number of the estimated ten to thirty million Chinese who lost their lives in the war, a number that far surpasses the half million or more Japanese noncombatants who died at the hands of US bombing, and may have exceeded Soviet losses to Nazi invasion conventionally estimated at 20 million lives.22 In that and subsequent wars it would be the signature barbarities such as the Nanjing Massacre, the Bataan Death March, and the massacres at Nogunri and My Lai rather than the quotidian events that defined the systematic daily and hourly killing, which would attract sustained attention, spark bitter controversy, and shape historical memory.

World War II remains indelibly engraved in American memory as the “Good War” and indeed, in confronting the war machines of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, the United States played a critical role in defeating aggressors and opening the way for a wave of decolonization that swept the globe in subsequent decades. It was also a war that catapulted the United States to global supremacy, and established the institutional foundations for the global projection of American power in the form of a vast array of insular territories and a network of permanent and ever growing military bases as well as unrivaled technological supremacy and military power.23 Against these factors we turn to a consideration of the US firebombing and atomic bombing of Japan in history, memory, and commemoration.

II. The Firebombing and Atomic Bombing of Japanese Cities: History, Memory, Culture, Commemoration

A. The US occupation and the shaping of Japanese and American memory of the bombing

Basic decisions by the Japanese authorities and by Washington and the US occupation authorities shaped Japanese and American perceptions and memories of the firebombing and atomic bombing. Throughout the six month period from the March 9 attack that destroyed Tokyo until August 15, 1945, and above all in the wake of the US victory in Okinawa in mid-June 1945, a Japanese nation that was defeated in all but name continued to spurn unconditional surrender, eventually accepting the sacrifice of more than half a million Japanese subjects in Okinawa and Japan to secure a single demand: the safety of the emperor. In preserving Hirohito on the throne and choosing to rule indirectly through the Japanese government, the US did more than place severe constraints on the democratic revolution that it sought to launch under occupation auspices. It also assured that there would be no significant

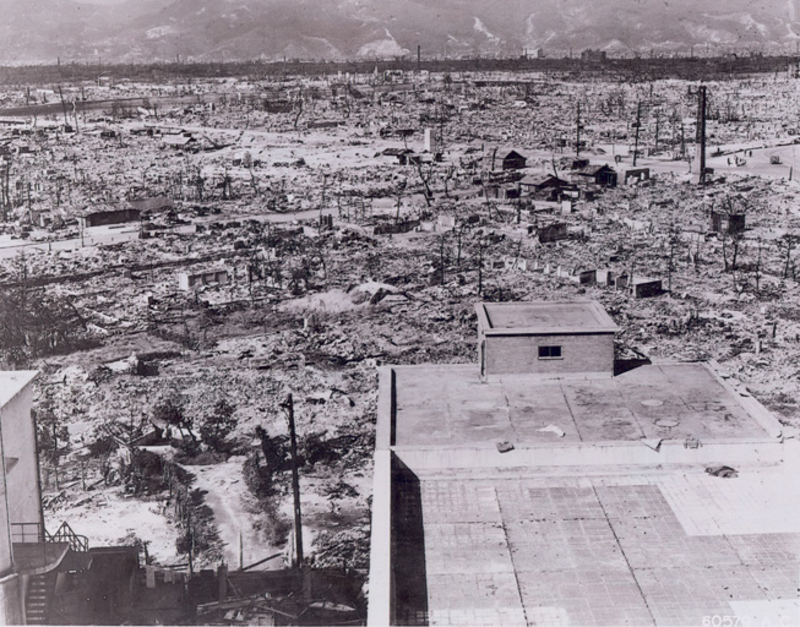

Hiroshima after the bomb. US National Archives |

Japanese debate over war responsibility or the nature of the imperial or imperial-military system in general, and the decision to sacrifice Okinawa and Japan’s cities with massive loss of life in particular.

From the outset of the occupation, the US imposed tight censorship with respect to the bombing, particularly the atomic bombing. This included prohibition of publication of photographic and artistic images of the effects of the bombing or criticism of it. Indeed, under US censorship, there would be no Japanese public criticism of either the firebombing or the atomic bombing. While firebombing never emerged as a major subject of American reflection or self-criticism, the atomic bombing did. Of particular interest is conservative and military criticism of the atomic bombing, including that of Navy Secretary James Forrestal, and Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, John Foster Dulles and a range of Christian thinkers such as Reinhold Niebuhr. Thus Sec. of War Henry Stimson worried about the “growing feeling of apprehension and misgiving as to the effect of the atomic bomb even in our own country.”24

As Ian Buruma observes, “News of the terrible consequences of the atom bomb attacks on Japan was deliberately withheld from the Japanese public by US military censors during the Allied occupation-even as they sought to teach the natives the virtues of a free press. Casualty statistics were suppressed. Film shot by Japanese cameramen in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the bombings was confiscated. Hiroshima, the famous account written by John Hersey for The New Yorker, had a huge impact in the US, but was banned in Japan. As [John] Dower says: ‘In the localities themselves, suffering was compounded not merely by the unprecedented nature of the catastrophe…but also by the fact that public struggle with this traumatic experience was not permitted.'”25 The US occupation authorities maintained a monopoly on scientific and medical information about the effects of the atomic bomb through the work of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, which treated the data gathered in studies of hibakusha as privileged information rather than making the results available for the treatment of victims or providing financial or medical support to aid victims. The US also stood by official denial of the ravages associated with radiation.26 Finally, not only was the press tightly censored on atomic issues, but literature and the arts were also subject to rigorous control prior.

This did not mean suppression of all information about the atomic bombing or the firebombings. Washington immediately announced the atomic bomb’s destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and released the iconic photographs of the mushroom cloud. It soon made available images of the total devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki depicting the ravages of cities reduced to rubble and devoid of human life, thereby demonstrating the Promethean power of the victor.

The US would celebrate the power of the bomb in powerful visual statements of the birth of the nuclear era that would be directed at the entire world on August 6, on August 9 and in the decades that followed, both in officially controlled photographic images and in privileged reportage, notably that of New York Times science reporter William R. Laurence. What was banned under the occupation were close-up images of victims whether of the firebombing or the atomic bombing captured on film by Japanese photographers, that is, the human face of the atomic holocaust.

Bodies of people trapped and burned as they fled through a street during the attack on the night of March 9-10. Photograph by Ishikawa Koyo. |

The Japanese authorities had reasons of their own for highlighting atomic bomb imagery while suppressing imagery of the firebombing. They include the fact that the dominant victimization narrative was preferable to having to engage war issues centered on Japanese aggression and war atrocities. Moreover, Japanese authorities preferred to emphasize the atomic bomb over the fire bombing for at least two reasons. First, it suggested that there was little that Japanese authorities or any nation could have done in the face of such overwhelming technological power. The firebombing, by contrast raised uncomfortable issues about the government’s decision to perpetuate the war through six months of punishing bombing with no alternative except defeat. Second, as Cary Karacas has argued, Japan’s bombing of Chongqing and other Chinese cities, including the use of Unit 731’s bio-weapons, raised uncomfortable questions about its own bombing.27

B. Firebombing and atomic bombing in Japanese literature and art

The atomic bomb experience gave rise to an outpouring of Japanese (and later international) literary and artistic responses that rank among the outstanding cultural achievements of the twentieth century extending across multiple genres and giving rise to a literary genre of Genbaku bungaku or atomic-bomb literature. These include haiku, tanka and linked poetry, short stories, novellas and children’s stories, dramas for tv and stage, manga, film, animation, memoirs, diaries, biographies and autobiographies, historical and journalistic accounts, photographs and photographic essays, murals, paintings, and drawings. While many of the signature works are by survivors, others constitute literary and artistic responses by a range of writers and artists, Japanese, American and international, who have responded to the bomb and the plight of the victims in the decades since the bombing.28 Among the authors, artists, photographers, filmmakers, anime and manga artists are many of Japan’s most eminent literary and artistic lights. A partial list would include Kurihara Sadako and Toge Sankichi (poets), Ibuse Masuji, Oe Kenzaburo and Hayashi Kyoko (novelists), Nakazawa Keiji (manga artist), Maruki Iri and Toshi (painters), Kurosawa Akira and Miyazaki Hayao (film directors), Matsushige Toshio, Yamahata Yosuke, Fukushima Kikujiro and Domon Ken (photographers), and Nagai Takashi (physician). And among international artists: Allen Ginsberg (poet), Stanley Kramer (film director), John Hersey (writer), Marguerite Duras (writer), Robert Lifton (psychiatrist), and Alain Resnais (film director). No less important, and no less vivid and important, than these literary, artistic and scholarly contributions are the words and images provided by children and citizen hibakusha inscribing their personal experiences of the bomb, most famously Unforgettable Fire: Pictures Drawn by Atomic Bomb Survivors.29 This literary and artistic outpouring perhaps has no parallel in the range and emotional depth of the responses to a twentieth century historical event. Indeed, viewed collectively, they constitute among the most important contributions to peace thought through the arts in human history. If we live in an era that may be called the Nuclear Age, the literary, artistic and citizen representations of the bomb and the hibakusha experience constitute among humanities’ most precious creative achievements, ones that open the path to an epoch of peace and human fulfillment rather than the war and destruction that many have seen as the dominant legacy of the long twentieth century.

Here I wish to pose a difficult question for which I have no confident answer. We have noted that the cumulative death and injury tolls as well as the destruction of the built environment from area bombing in Europe and Japan exceeded those of the atomic bombing. Moreover, area bombing not only preceded the atomic bombing but came to be legitimized in the sense of being subject to no significant international legal challenges as were, for example, the use of forced labor or the sexual slaves of the Japanese military known as the comfort women. And, above all this became a core element of the American military in each of the major wars fought in the six decades since World War II. Yet, although journalists, photographers and historians recorded the events, and although the US Strategic Bombing Survey interviewed survivors of the firebombing, when we turn to literature and the arts in Japan and internationally, including the United States, these cataclysmic events have barely been noted in the decades since 1945.

Among notable exceptions to the literary and artistic silencing of the firebombing, perhaps best known in both Japan and the United States is Grave of the Fireflies (Hotaru no haka), Nosaka Akiyuki’s semi-autobiographical novel made into a successful 1988 film directed by Takahata Isao and beautifully animated by Studio Ghibli. Set in Kobe, it records the terrifying bombing through the eyes of 14-year old Seita and his 4-year old sister Setsuko, who lose their mother in the flames and themselves die in poverty in the aftermath of Japan’s surrender.30 The surviving victims of firebombing doubtless recorded their experiences in diaries, poems and memoirs. Yet nearly all of these responses to the firebombing remain confined to the private sector, the individuals and families of their creators.

Grave of the Fireflies |

How are we to comprehend the fact that while 66 Japanese cities were leveled by firebombing, taking the lives of several hundred thousand Japanese, the experience generated relatively little literature or art, and that little, with few exceptions, was neither noted nor long remembered compared to the monumental production derived from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki experience? How explain the difference despite the fact that censorship applied to both the literature and art of the firebombing and the atomic bombing during the occupation? Clearly multiple factors were and are at work:

The United States, in substantiating its claim as the unrivaled superpower, highlighted the atomic bomb as the critical ingredient in Japan’s surrender. It is worth recalling however, that six months of firebombing had laid waste to Japan and revealed the inability to defend the skies, but it had failed to force surrender. The atomic bombs further underlined the nature of American power, but it is important to note what the official US narrative elides: the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on August 8, one day before Nagasaki, was critical to the Japanese surrender calculus.

With more than 200,000 dead by the end of 1945 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and with many more dying in subsequent years, nuclear weapons emerged as the nonpareil weapon of mass destruction, their power magnified by the mystique of radiation. This theme would recur in fantasy and nightmare throughout the postwar, shaping the Japanese and American imagination, and indeed the global imaginary. It would shape feature film representations of the bomb as well as the fantasies played out in the press, as in the fears of a nuclear attack on New York City, and in literature and art.31 Here Dr. Strangelove is perhaps the signature international creation, but equally important are the fantasies played out in the press, as in the fears of a nuclear attack on New York City. In addition, the high degree of US censorship and disinformation, including official denial of the effects of radiation, had the effect of focusing attention on understanding a weapon that continued to kill with the passage of time. The fact that the Soviet-American conflict, the defining geopolitical clash of the postwar era, was organized around nuclear rivalry had the effect of drawing further attention to nuclear issues: here both the Pentagon and the world peace movement were equally fixated on atomic weapons despite the fact conventional bombing was the everyday reality of all subsequent wars fought by the United States and others.

Subsequent developments powerfully drew attention to the atomic bomb. The Lucky Dragon #5 Incident of 1954, resulting in the irradiation of 23 Japanese fishermen (and the death of one) caught in the US hydrogen bomb test at Bikini, ignited the world anti-nuclear movement with Japan as the epicenter of protest from that time forward.32 The following year, 1955, the Hiroshima Memorial Museum was established, giving the anti-nuclear movement a highly visible shrine backed by the Hiroshima and Japanese governments. Hiroshima would become a mecca for Japanese and international visitors as a site for peace education and a symbol of peace as well as of Japanese suffering. (Nagasaki would build its own memorial museum, but both Japanese and international attention have always focused on Hiroshima).

The Japanese government also underlined the distinction between nuclear and firebombing survivors not only in its lavish funding for the museums in the two cities, but by making available funds to provide medical care for the victims of the atomic bombing. It is worth underlining the fact that it was the Japanese government and not the US government that provided, and continues to provide, substantial funds for the hibakusha. The larger numbers of surviving victims of firebombing never received either recognition or official support from national or local government for medical care or property losses, and they certainly never drew either Japanese or international attention. In short, while the surviving victims of the atomic bomb were a continuing reminder to Japanese of their victimization, bomb survivors in other cities were expected to embrace the forward looking national agenda of reconstruction to build Japan again into an industrial power that would rise not under the banner of the military but under permanent US military occupation, a US nuclear umbrella and a peace constitution.

With the end of the occupation, there was a flourishing of atomic literature and art, including novels, poetry, visual arts and photography that had previously been censored and now found a ready reception among publishers and readers, conveying with sensitivity, nuance and pathos the nature of experiences that had the capacity to deeply move Japanese and international readers and viewers, often by understatement, or even silence. Two examples may illustrate the citizen literary and documentary response.

To the Lost33

Yamada Kazuko

When loquats bloom

When peach blossoms in the peach mountain bloom

When almonds are as big as the tip of the little finger

My boys

Please come.

Nagai Kayano (5 at the time of bombing, recalled)

My brother and I were in the mountain house in Koba. My mother came from Nagasaki with clothes.

“Mom, did you bring Kaya-chan’s too?” I asked right away. My mother said, “yes. I brought lots of Kaya-chan’s clothes, too,” and stroked my head.

This was the last time that she stroked me.

My mother said, “When there’s no air raid next, come down to Nagasaki again, okay?” And she left right away in a great hurry.34

In much of the literature and memoir, as in the film, anime, photography and painting, there is an immediacy of the human experience that transcends argument and debate and conveys powerful human emotions including deep sympathy for victims, many of them women and children. In some can also be found a sense, rarely explicitly stated, of the inhumanity of the assailant.

From “Fire”, Second of The Hiroshima Panels by Maruki Iri and Toshi |

C. Firebombing and atomic bombing in Japanese and American museums, monuments and memory

National and local state governments everywhere wield important commemorative powers as one weapon in the nationalist arsenal through their ability to build and finance museums and monuments that guard public memory of critical historical events, yet their policies may also become the locus of public controversy.

The story line here closely parallels that of literature and the arts. The high profile atomic bomb memorial museums at Hiroshima and Nagasaki-funded initially primarily by prefectural and city governments but subsequently lavishly supported by Tokyo in building two enormous national memorial sites-has produced a major, perhaps THE major, site of national commemoration, mourning, and public education in Japan. Indeed, not only are the memorial museums (notably Hiroshima) among the most important sites of Japan’s ubiquitous school education trips, they are also arguably the single largest international, particularly American, magnet for tourists. See here and here. A 1994 Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Assistance Act set in motion the creation of national memorials, which opened on August 1, 2002 in Hiroshima and July 2003 in Nagasaki. Its mission: “To pray for peace and pay tribute to the survivors. To collect and provide A-bomb-related information and materials, such as memoirs of the A-bombing”. This meant that, at least until recently, both memorial museums provided no contextualization of the bombing in light of the history of Japanese colonialism, the invasion of China and Southeast Asia, or questions of war atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre or the comfort women. Their mission was understood to be that of giving voice to Japanese victims of the atomic bombing. Tout court. In recent years, both have introduced materials on Japan during the fifteen-year war, with Nagasaki providing a far more extensive and deeper introduction to the nature of Japanese colonialism and war at the expense of Asian people.

What then of the treatment of commemoration of the firebombing that destroyed 66 Japanese cities in 1945? First, it is notable that there is no national or even prefectural site of commemoration of the firebombing. National and most local governments-important exceptions include the cooperation of local governments in Nagoya and Osaka with citizens groups commemorating the bombing-have chosen not to memorialize the hundreds of thousands who died and were injured, and the millions who lost their homes and were forced to evacuate as a result of fire bombing35. In striking contrast to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, local and national governments have trained their eyes on the future, rebuilding the cities while doing their best to forget the trauma of firebombing and denying official responsibility for the victims. To my knowledge, there is no single state-sponsored monument to the victims of the firebombing preserved for reflection or education in ways comparable to Hiroshima’s atomic dome, which was embraced not only by Hiroshima and Tokyo, but was also designated as a World Heritage site.36

Nevertheless, firebombing has not entirely disappeared down the memory hole. The most visible site, especially for international researchers and visitors, The Tokyo Air Raid and War Damages Resources Center is an invaluable education and research center documenting and exhibiting the firebombing. Opened in 2002 and expanded in 2007, it was built in the absence of direct financial or logistical support by the Tokyo authorities. But approximately ten others, notably Peace Aichi and Peace Osaka, all spearheaded by citizens groups, make important contributions to commemoration and the continued viability of peace thought. While all of these are far more modest than the Hiroshima and Nagasaki memorials, the Tokyo Center is a substantial resource, and it is free of government controls. This means in particular that, under the leadership of writer-researcher peace activist Saotome Katsumoto, it can examine critically not only the US bombing but also the Japanese and American war efforts.37 It cannot, however, gain the cachet of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Centers with their hundreds of thousands of Japanese and international visitors and high national and international profile.

Nevertheless, the resource base for the study of the firebombing of Japan, particularly of Tokyo, is growing. Bret Fisk and Cary Karacas have established Japan Air Raids.org, an important bilingual historical archive including a range of documents and art pertaining to the US air raids against Japan including a nearly complete set of the 108 reports of the US Strategic Bombing Survey; the 5 volume set of the Tokyo Daikushu–Sensaishi(“Great Tokyo Air Raid-War Damage Documentation“), which conveys the voices of survivors and much more.

|

Nihei Haruyo, eight years old at the time of the Tokyo firebombing, shows the site of the bombings at the Tokyo Air-Raid Center (Photograph Satoko Norimatsu) |

Comparison with the National Showa Memorial Museum (Showakan) is instructive. Where the Tokyo Center documents the disasters suffered by Tokyo’s citizens in the firebombing that destroyed the city (but not the Imperial Palace), the Showakan displays the nation’s loyal subjects going about their work, supporting the troops, engaging in neighborhood fire-fighting drills, raising their children and working to support families and the war. Calm reigns as every citizen, child, mother, soldier, grandparent follows his or her assignment to the letter. Not a single exhibit (as of 2011) conveys a sense of the terror and destruction of the bombing or, indeed, any sign of disorder.

The result is that the major national sites of war memory available to Tokyo’s citizens and visitors are the Yasukuni Shrine and the Showakan, each in its way a monument to the Emperor, to Shinto nationalism, and the war effort, and each eliding the trauma to which citizens of Tokyo and 66 other Japanese cities were subjected in the final months of the war.

One museum sponsored by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government does contain an exhibit on the bombing on its sixth floor. That is the Edo-Tokyo Museum in Sumida Ward at Ryogoku Station which, like Yasukuni and the Showakan, conveys little sense of terror or destruction that the bombing wrought.

Viewed from another angle, through official Japan’s suppressing or downplaying the firebombing, America’s nuclear supremacy provides reassurance for Japanese leaders committed to maintaining Japan’s subordinate position in the US-Japan alliance in perpetuity: the US nuclear umbrella is the most powerful guarantee of Japan’s security. Thus, in drawing attention to the atomic bomb, Japanese leaders are simultaneously reaffirming their core diplomatic choice in the contemporary era.

The issues of Japanese memory and silence on the bomb invites comparison with the controversy in the United States over the Smithsonian exhibition on the fiftieth anniversary of Japan’s surrender in 1995. A furor arose when historians and museum staff crafted an exhibition that included recognition of the human toll of the bomb. The controversy pivoted around a single powerful image.

|

Lunchbox of junior high school student Orimen Shigeru. (Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum) |

Orimen Shigeru’s carbonized lunchbox was among the artifacts found and collected at the Hiroshima Memorial Museum. His mother found the uneaten lunchbox with his body on August 9 after three days of searching.

When the exhibitors proposed to include the lunchbox at the Smithsonian, the issue went viral, culminating in a unanimous Senate resolution which condemned the exhibit in its entirety. The exhibition eventually went forward with a single item: The Enola Gay, the B-29 that had dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. The lunchbox had the symbolic capacity to undermine the national narrative of patriotism, power and honor by calling to mind the bomb’s victims.38 The result illustrated the immense difficulty Americans have long faced, and continue to face, in finding an appropriate framework for celebrating the moment that brought the United States to the pinnacle of its power.

Many Americans share with the Japanese people, and with people throughout much of the world, deep sympathy for the victims of the atomic bomb. Carolyn Mavor provides a compelling example of that empathetic understanding in her introductory essay to elin o’Hara slavick’s Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography (pp. 20-21)

I do not understand. I cannot comprehend the fact that the famed silver monster plane dropped Little Boy on little boys and little girls, like the beautiful two-year-old Sadako Sasaki, who would become the inspirational paper-crane-folding, speed running, kimono-wearing, peace-loving teenager who finally succumbed to her radiation-poisoning at age fourteen. Obscene is the fact that the pilot of the plane, Paul Tibbets, had the name of his mother, Enola Gay, painted on the nose of the plane, just days before the mission. How could a plane named for one’s mother kill so many mothers and children?

We reflect on the fact that there is no Sadako of the firebombing of Japanese cities, no carbonized lunchbox relic known to the world, or even to Japanese children. Yet there was precisely the killing of myriad mothers and children in those not quite forgotten raids. We need to expand the canvas of our imagination to encompass a wider range of victims of American bombing in this and other wars, just as Japanese need to set their experience as bomb victims against the Chinese and Asia-Pacific victims of their war and colonialism. Nor should American responsibility for its bomb victims end with the recovery of memory. It requires a sensibility embodied in official apology and reparations for victims, and a consciousness embodied in public monuments and national military policies that is fundamentally at odds with American celebrations of its wars.

Reflection

This article has sought to understand the political dynamics that lie behind the differential treatment of the firebombing and atomic bombing of Japan in Japan and the United States, events that brought disaster to the Japanese nation, but also brought to an end a bitter war and paved the way for the rebirth of a Japan stripped of its empire (but not its emperor) and prepared to embark on the rebuilding of the nation under American auspices. We have been equally interested in the human consequences of the US targeting civilian populations for annihilation as a central strategy of its airpower from late 1944 and the nature of subsequent ways of war. While the atomic bomb has overshadowed the firebombing in most realms in the nearly seven decades since 1945, notably as a major factor in assessing US-Soviet conflict and explaining the structure of a “Cold War” in world politics, we have shown not only that the firebombing took a greater cumulative toll in human life than the atomic bombs, but importantly that it became the core of US bombing strategy from that time forward.

We can view this from another angle. It appears that in the squaring off of the two superpowers, mutual targeting with atomic weapons was the centerpiece of direct conflict, while proxy fights, as in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan, were fought with bombs ranging from firebombs to cluster bombs to defoliants. The drone opens a new page in this history of state terror. In each of these, the United States essentially monopolized the skies in the dual sense that it alone carried out massive bombing, and its own homeland, and even its military bases in the US and throughout the world, were never bombed.

This would begin to change in the last decade, culminating in the 9.11 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, instantly shredding the image of US invulnerability to foreign attack short of nuclear attack, and giving rise to a language of weapons of mass destruction and terrorism. It was a language that elided state terrorism, notably the systematic killing of civilian populations that was a hallmark of US warfare from 1944 to the present, while focusing attention on non-state actors such as al-Qaeda. There is a second major change in the international landscape of military conflict. That is the most important technological change of the postwar era: the use by (above all) the United States of drones to map and bomb on a world scale. Each of these inflects above all the possibilities of bombing independent of nuclear weapons.

In drawing attention to US bombing strategies deploying “conventional weapons” while keeping nuclear weapons in reserve since 1945, the point is not to deny the critical importance of the latter in shaping the global balance of power/balance of terror. Far from it. It is, however, to suggest new perspectives on our nuclear age and the nature of warfare in the long twentieth century and into the new millennium.

This text is slightly modified from a chapter that appeared in Kinnia Yau Shuk-ting, ed., Natural Disaster and Reconstruction in Asian Economies. A Global Synthesis of Shared Experiences (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

Recommended Citation: Mark Selden, “Bombs Bursting in Air: State and citizen responses to the US firebombing and Atomic bombing of Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 3, No.4, January 20, 2014.

Mark Selden is a Senior Research Associate in the East Asia Program at Cornell University and a coordinator of the Asia-Pacific Journal. His books include The Atomic Bomb: Voices From Hiroshima and Nagasaki (with Kyoko Selden), China, East Asia and the Global Economy: Regional and historical perspectives (with Takeshi Hamashita and Linda Grove), The Resurgence of East Asia: 500, 150 and 50 Year Perspectives (with Giovanni Arrighi and Takeshi Hamashita), and War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century (with Alvin So); Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance (with Elizabeth Perry). His homepage is www.markselden.info/.

Related articles

• Bret Fisk and Cary Karacas, The Firebombing of Tokyo and Its Legacy: Introduction

Notes

1 I am grateful for critical responses to earlier drafts of this paper from John Gittings, Cary Karacas and Satoko Norimatsu.

2 A small number of works have problematized the good war narrative by drawing attention to US atrocities in the Asia-Pacific War, typically centering on the torture, killing and desecration of captured Japanese soldiers. These include Peter Schrijvers, The GI War Against Japan. American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific During World War II (New York: NYU Press, 2002) and John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon, 1986). Two recent works closely assess the bombing of noncombatants in both Japan and Germany, and the ravaging of nature and society as a result of strategic bombing that has been ignored in much of the literature. A. C. Grayling, Among the Dead Cities: The history and moral legacy of the WW II bombing of civilians in Germany and Japan (New York: Walker & Company, 2006), provides a thoroughgoing assessment of US and British strategic bombing (including atomic bombing) through the lens of ethics and international law. See also Michael Bess, in Choices Under Fire. Moral Dimensions of World War II (New York: Knopf, 2006), pp. 88-110.

3 Grayling, Among the Dead Cities, pp. 90-91.

4 Michael Sherry, “The United States and Strategic Bombing: From Prophecy to Memory,” in Yuki Tanaka and Marilyn B. Young, eds., Bombing Civilians: A twentieth century history (New York: The New Press, 2009), pp. 175-90; Cary Karacas, “Imagining Air Raids on Tokyo, 1930-1945,” paper presented at the Association for Asian Studies annual meeting, Boston, March 23, 2007. Sherry traces other prophecies of nuclear bombing back to H.G. Wells 1913 novel The World Set Free.

5 David Fedman and Cary Karacas. “A Cartographic Fade to Black: Mapping the Destruction of Urban Japan During World War II.” Journal of Historical Geography 36, no. 3 (2012), pp. 306–28.

6 Robert Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986), pp. 596-97; Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Gate, The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945. Vol. 5, The Army Air Forces in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953; 1983 Office of Air Force History imprint) pp. 609-13; E. Bartlett Kerr, Flames Over Tokyo (New York: Fine, 1991), pp. 146-50; Barrett Tillman, Whirlwind. The Air War Against Japan, 1942-1945, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010) pp. 134-73; Kenneth P. Werrell, Blankets of Fire. U.S. Bombers over Japan during World War II (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996) pp. 150-93.

7 Sherry, Air Power, p. 276. A detailed photographic record, including images of scores of the dead, some burnt to a crisp and distorted beyond recognition, others apparently serene in death, and of acres of the city flattened as if by an immense tornado, is found in Ishikawa Koyo, Tokyo daikushu no zenkiroku (Complete Record of the Great Tokyo Air Attack) (Tokyo, 1992); Tokyo kushu o kiroku suru kai ed., Tokyo daikushu no kiroku (Record of the Great Tokyo Air Attack) (Tokyo: Sanseido, 1982), and Dokyumento: Tokyo daikushu (Document: The Great Tokyo Air Attack) (Tokyo: Yukeisha, 1968). See the special issue of the Asia-Pacific Journal edited by Bret Fisk and Cary Karacas, The Firebombing of Tokyo: Views from the Ground, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 3 No 1, January 17, 2011.

8 Dokyumento. Toky o daikushu, pp. 168-73.

9 The Survey’s killed-to-injured ratio of better than two to one was far higher than most estimates for the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki where killed and wounded were approximately equal. If accurate, it is indicative of the immense difficulty in escaping for those near the center of the Tokyo firestorm on that windswept night. The Survey’s kill ratio has, however, been challenged by Japanese researchers who found much higher kill ratios at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, particularly when one includes those who died of bomb injuries months and years later. In my view, the SBS estimates both exaggerate the killed to injured ratio and understate the numbers killed in the Tokyo raid. The Committee for the Compilation of Materials on Damage Caused by the Atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombing (New York: Basic Books, 1991), pp. 420-21; Cf. U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, Field Report Covering Air Raid Protection and Allied Subjects Tokyo (n.p. 1946), pp. 3, 79. In contrast to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which for fifty years has been the subject of intense research by Japanese, Americans and others, the most significant records of the Tokyo attack are those compiled at the time by Japanese police and fire departments. The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey study of Effects of Air Attack on Urban Complex Tokyo-Kawasaki-Yokohama (n.p. 1947), p. 8, observes that Japanese police estimates make no mention of the numbers of people missing. In contrast to the monitoring of atomic bomb deaths over the subsequent six decades, the Tokyo casualty figures at best record deaths and injuries within days of the bombing at a time when the capacity of the Tokyo military and police to compile records had been overwhelmed. Many more who died in the following weeks and months go unrecorded.

10 Barrett Tillman, Whirlwind, pp. 144-45 documents the startling lack of preparedness of Japanese cities to cope with the bombing. “One survey noted, ‘The common portable fire extinguisher of the C2, carbon tetrachloride, foam, and water pump can types were not used by Japanese firemen.’ In one of the most urbanized nations on earth there were four aerial ladders: three in Tokyo and one in Kyoto. But in 1945 only one of Tokyo’s trucks was operational . . . Their 500-gpm pumps were therefore largely useless.”

11 Karacas, “Imagining Air Raids,” p. 22; Thomas R. Havens, Valley of Darkness. The Japanese People and World War II, (New York: WW Norton 1978), p. 163, puts the number of urban residents evacuated to the countryside overall at 10 million. He estimates that 350,000 students from national schools in grades three to six were evacuated in 1944 and 100,000 first and second graders in early 1945.

12 John W. Dower, “Sensational Rumors, Seditious Graffiti, and the Nightmares of the Thought Police,” in Japan in War and Peace (New York: The New Press, 1993), p. 117. United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report, Vol I, pp. 16-20.

13 Sahr Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage, p. 1.

14 Bret Fisk and Cary Karacas, The Firebombing of Tokyo and Its Legacy: Introduction, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 3 No 1, January 17, 2011. Fisk and Karacas draw on Overall Report of Damage Sustained by the Nation During the Pacific War, Economic Stabilization Agency, Planning Department, Office of the Secretary General, 1949, which may be viewed here.

15 The numbers killed, specifically the numbers of noncombatants killed, in the Korean, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq wars were greater, but each of those wars extended over many years and bombing accounted for only a portion of deaths.

16 It may be tempting to consider whether the US willingness to kill such massive numbers of Japanese civilians can be understood in terms of racism, a suggestion sometimes applied to the atomic bomb. Such a view is, I believe, negated by US participation in area bombing attacks at Dresden in 1944. Cf. John Dower’s nuanced historical perspective on war and racism in American thought and praxis in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986). In Year 501: The Conquest Continues (Boston: South End Press, 1993) and many other works, Noam Chomsky emphasizes the continuities in Western ideologies that undergird practices leading to the annihilation of entire populations in the course of colonial and expansionist wars over half a millennium and more. Matthew Jones, After Hiroshima. The United States, Race and Nuclear Weapons in Asia, 1945-1965 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010). Jones emphasizes factors of race, but not racism in the Pacific War, the atomic bombing (there is no mention of the firebombing) and the Korean and Vietnam Wars. He considers US consideration of use of the atomic bomb in all of these, noting US plans to drop an atomic bomb on Tokyo when more bombs became available by the end of August, if Japan had not yet surrendered.

17 The master work on the world history of peace thought and activism is John Gittings, The Glorious Art of Peace. From the Iliad to Iraq (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), chapters 5-7.

18 Geoffrey Best, War and Law Since 1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994) pp. 180-81. Could be interpreted . . . but at the Tokyo Trials, defense attempts to raise the issue of American firebombing and the atomic bombing were ruled out by the court. It was Japan that was on trial.

19 Bombing would also be extended from cities to the countryside, as in the Agent Orange defoliation attacks that destroyed the forest cover and poisoned residents of sprayed areas of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. See Fred A. Wilcox, Scorched Earth. Legacies of Chemical Warfare in Vietnam (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2011).

20 elin o’Hara slavick, Bomb After Bomb. A Violent Cartography (Milan: Charta, 2007), p. 35.

21 Mark Selden, “Japanese and American War Atrocities, Historical Memory and Reconciliation: World War II to Today,” Japan Focus, April 15, 2008. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus contains scores of articles on war, atrocities, and historical memory in the Pacific War .

22 An insightful discussion of Japanese war crimes in the Pacific, locating the issues within a comparative context of atrocities committed by the US, Germany, and other powers, is Yuki Tanaka’s Hidden Horrors: Japanese Crimes in World War II. Takashi Yoshida, The Making of the “Rape of Nanking”: History and Memory in Japan, China and the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006) examines the understanding of the Nanjing Massacre in each country.

23 Mark Selden, “String of Pearls: The Archipelago of Bases, Military Colonization, and the Making of the American Empire in the Pacific,” International Journal of Okinawan Studies, Vol 3 No 1, June 2012 (Special Issue on Islands) pp. 45-62.

24 Jones, After Hiroshima, pp. 24-25. Peter Kuznick, “The Decision to Risk the Future: Harry Truman, the Atomic Bomb and the Apocalyptic Narrative,” suggests that those who held that dropping atomic bombs on Japan was morally repugnant and/or militarily unnecessary in the immediate postwar period included Admiral William Leahy, General Dwight Eisenhower, General Douglas MacArthur, General Curtis LeMay, General Henry Arnold, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers, Admiral Ernest King, General Carl Spaatz, Admiral Chester Nimitz, and Admiral William “Bull” Halsey. The fact of the matter, however, is that, with the exception of a group of atomic scientists, these criticisms were raised only in the postwar.

25 Ian Buruma, “Expect to be Lied to in Japan,” New York Review of Books, November 8, 2012. See See also, Monica Braw, The Atomic Bomb Suppressed. American Censorship in Occupied Japan (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1991). See the extensive discussion of censorship in Takemae Eiji, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy (London: Continuum, 2002), espec. pp. 382-404, and John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, espec. pp. 405-40.

26 William R. Laurence, U.S. Atom Bomb Site Belies Tokyo Tales: Tests on New Mexico Range Confirm that Blast, and not Radiation Took Toll, New York Times, September 12, 1945. Quoting Gen. Leslie Groves, director of the atom bomb project and the point man on radiation denial: “The Japanese claim that people died from radiation. If this is true, the number was very small.”

27 Cary Karacas, “Place, Public Memory, and the Tokyo Air Raids.” Geographical Review 100, no. 4 (October 1, 2010), pp. 521–37.

28 Some useful bibliographies on English language sources on the literary and artistic responses to the atomic bomb are Annotated Bibliography for Atomic Bomb Literature from the Alsos Digital Library (2012) (literature, film, memoir, bibliographies); Tomoko Nakamura, English Books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki: An On-line Bibliography (2004) (Literature, memoirs, photography, research reports); Amazon lists 2,048 works under Atomic Bomb. Kyoko and Mark Selden, eds., The Atomic Bomb: Voices From Hiroshima and Nagasaki offers a range of literary, artistic, memoir and documentary works (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1989). Nihon no genbaku bungaku (Japan’s atomic bomb literature), Tokyo: Herupu Shuppansha, 1983) is the most extensive Japanese language collection of atomic literature.

29 The Tokyo firebombing also generated important artist expressions, notably the eleven paintings of “That Unforgettable Day–The Great Tokyo Air Raid through Drawings.”, But in contrast to the Japanese and international attention that Unforgettable Fire received, the Tokyo firebombing paintings have received little attention. Fisk and Caracas, “The Firebombing of Tokyo and Its Legacy: Introduction.”

30 A YouTube upload of the English language dubbed version of Grave of the Fireflies.

31 Mick Broderick and Robert Jacobs bring the point home powerfully in their work on the fantasy of the atomic bombing of New York City, born in the New York Daily News on August 7, 1945 and continuing in art and fantasy to the present. Nuke York, New York: Nuclear Holocaust in the American Imagination from Hiroshima to 9/11.

32 See particularly See Matashichi Oishi, The Day the Sun Rose in the West. Bikini, the Lucky Dragon and I (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2011).

33 Trans. by Kyoko Selden, The Atomic Bomb, p. 122.

34 Trans. by Kyoko Selden, The Atomic Bomb, p. 222.

35 Cary Karacas kindly drew my attention to the role of some local governments in working with local citizens to memorialize bomb victims.

36 Not everyone welcomed the World Heritage designation. Jung-Sun N. Han notes that the Chinese government expressed reservations about the designation of the site: “During the Second World War, it was the other Asian countries and peoples who suffered the greatest loss in life and property. But today there are still few

people trying to deny this fact of history. As such being the case, if Hiroshima

nomination is approved to be included on the World Heritage List, even though

on an exceptional basis, it may be utilised for harmful purpose by these few

people. This will, of course, not be conducive to the safeguarding of world peace

and security.” “Conserving the Heritage of Shame: War Remembrance and War-related Sites in

Contemporary Japan,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 42:3, 2012, p. 499.

37 See Reconciliation and Peace through Remembering History: Preserving the Memory of the Great Tokyo Air Raid 歴史の記憶」から和解と平和へ東京大空襲を語りついで trans. by Bret Fisk, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 3 No 4, January 17, 2011.

38 Laura Hein and Mark Selden, eds. Living With the Bomb. American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1997), Introduction, George H. Roeder, Jr., “Making Things Visible: Learning from the Censors,” and Yui Daizaburo, “Between Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima/Nagasaki: Nationalism and Memory in Japan and the United States.”