Almost every one or two weeks a large envelope arrives in my mailbox. Opening it up invariably reveals a flier, newsletter or newspaper, often accompanied by a handwritten note with a tailored message. At the risk of sounding facetious, only my mobile phone provider is as punctual and frequent. But the deliveries are not from any commercial service. They are from a prisoner support group.

Japan’s justice system has been in the spotlight of late and for all the wrong reasons. With the recent release of Hakamada Iwao after serving over 40 years on death row, the nation’s police and prosecution have come in for intense criticism. Wrongful convictions happen in countries around the world and no judicial system is perfect. However, Hakamada’s case follows a spate of other high-profile wrongful convictions that were finally overturned, laying bare something very rotten in a system with a 99% conviction rate and an emphasis on extracting confessions from suspects.

The release of Hakamada proves what can be done with enough determination. The world’s longest-serving death row prisoner was finally freed after years of campaigning by his supporters. However, there are many other cases and some are surprisingly little known. Hoshino Fumiaki is one of the world’s longest-serving political prisoners and only the constant efforts of his supporters over decades will likely save him from dying behind bars.

Shienkai or kyūenkai are names for certain kinds of Japanese civic activist groups that typically form a support network for someone facing trial or campaigning for retrial, as well as lobbying to promote the subject’s cause. The groups have no legal status and are generally modest in scale. They are run by small teams of dedicated core volunteers that may be repeated across a network of sub-groups in other regions.

Support groups are active around the world on behalf of prisoners and some, such as Amnesty International, have acquired global recognition. Trial support groups have actually existed in Japan since the pre-war period. In the 1920’s there was a group that supported arrested members of the Japanese Communist Party and following the emancipation of the JCP after the war, the Party had new support networks to assist activists who ran into conflict with the police. However, as the New Left protest movements (which in Japan fiercely opposed the JCP) began to grow and clash with the authorities, there was a need for new kinds of support groups independent of the JCP.

The networks developed with volunteers and professionals to offer help to arrestees. Ostensibly, this took the form of encouraging them to resist confessing and maintain silence during interrogations (a stance known as kanmoku, or kanzen mokuhi). In other words, the arrested parties would refuse to cooperate with the police so they could take the case to court as a political crime. Such support groups were often started by family and associates, and were also populated by admirers and other activists. The group would work with lawyers, providing paralegal services and research in preparing court cases and applications for retrials.

This article will look at two examples of support groups associated primarily with 1970’s political cases that are still very active today.

1. Kyūen Renraku Sentā (Relief Liaison Center)

Kyūen Renraku Sentā (Relief Liaison Center, also known as Kyuen Renraku Center) is undoubtedly the most famous support group of its kind in Japan. Technically speaking, it is more like a network or an agency, out of which specific trial support groups operate. Formed in 1969 as a non-sectarian organization, its genesis came at a time when not only were thousands of young demonstrators being arrested and facing trial, the New Left was also splintering into more and more factions, creating ever greater difficulties for providing resources to members who were arrested. Kyūen Renraku Sentā initially focussed on so-called “non-sect” activists who did not have the support of a faction when they were arrested, though it would later come to represent activists from factions as well.

Its network consisted of lawyers willing to take on the sensitive cases, as well as an army of volunteers drawn from housewives, retirees, teachers and students. The lawyers themselves were not necessarily New Left per se; they were committed to defending civil liberties regardless of the politics of the students.

The JCP would not lend its network of lawyers to anti-JCP arrested students, sect or non-sect. These activists needed help and so Kyūen Renraku Sentā stepped in. The Center was able to put its resources to good use and was instrumental in countless trials. The sociologist Patricia G Steinhoff has estimated the number of people who participated in the support networks through the Center as between 25,000 and 50,000 at the height of the New Left protest movements in Japan. This was the intense cycle of protests in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s against the Vietnam War, the terms of the reversion of Okinawa (especially the continued presence of US military bases), and the 1970 renewal of the controversial Ampo security treaty between America and Japan. There were also intense campus conflicts, especially at the University of Tokyo and Nihon University, and the violent Sanrizuka protests against the construction of Narita Airport mobilized thousands of activists. KRS had some 1,000 emergency volunteers across various local groups during this time. Mass arrests on particularly volatile dates might mean that KRS’s lawyers were dealing with hundreds of activists being held at dozens of police stations all over the country on the same day.

The Center worked hard to educate young and often inexperienced activists about demonstrating. This included distributing fliers and materials giving practical advice about attending protests. Female demonstrators, for example, were advised to wear low-heeled shoes and cotton stockings (since nylon ones are flammable and there might be Molotov cocktails). A generation of activists also memorized the KRS 24-hour telephone number (591-1301) using the mnemonic goku iri, imi ooi (“to be in jail has much meaning”). Japanese arrestees do not have telephone privileges, so actually, and rather ironically, the person who would call the KRS was a police officer.

In this way, we can see how even in the mnemonic for its telephone number KRS fashioned a culture for fighting charges as a form of political resistance against the very police and justice system itself. Activists would say nothing, since to do so not only meant participating in the police tactics to wear them down during the long detention period, but also acknowledged the legitimacy of the state. Activists might not even give or confirm their name, which resulted sometimes in a detainee being identifiable only by a booking number.

After indictment (often many weeks after arrest), a trial support group would be formed within the Center’s network, typically led by relatives and friends, and also veteran volunteers. The Center acts like an umbrella over these groups. For example, various different groups will use KRS’s office as their contact and mailing address. While the conflagrations of 1968-1971 are the distant past, these practices still happen, such as for the student activists associated with the Hosei University conflict who have been arrested and tried in recent years. This is an ongoing dispute between the university and the student league Zengakuren and an unofficial Hosei student group called the Bunka Renmei, which has led to clashes at the Ichigaya campus. There have been 33 indictments since 2006 for trespassing, violating bylaws on assembling, obstructing government officials, and other offenses. In 2009 five activists were controversially charged under the Law for the Punishment of Acts of Violence, a pre-war law associated with organized crime. Their acquittal was finally upheld in February 2014.

The support group will meet regularly to organize the defence. Since political crimes are usually tried together, the support group might support all the defendants together, which also means a better pooling of time and resources.

As well as the initial detention period, lobby and support networks provide a lifeline during the long trial process, which is painfully dragged out in Japan as courts only sit for very short sessions spread out of over several months. After radical groups began to adopt more violent tactics, New Left activists in Japan faced increasing strictures due to the practice of “unconvicted detention”, where the activist would be held in special conditions until the result of the trial had been announced in a kind of legal limbo, neither on bail nor convicted.

The support groups meet defendants in prison, attend court sessions, correspond with the defendant, arrange things for them, bring supplies of food and clean clothes, assist the lawyers, and raise funds and publicity. And this also forms a valuable way for the family and friends to cope as well, especially if the case is a high-profile one resulting in a lengthy trial (often followed by retrials).

On top of organizing these legal support groups and dispatching lawyers, KRS has also helped mediate and lobby for other human rights causes, such as the successful “return” to Japan of the stateless children of the Sekigun-ha Yodogō hijackers and members of the Japanese Red Army. Since pulling off Japan’s first ever hijacking in 1970, the Yodogō group have been stuck in North Korea. They married and had children, and while the surviving hijackers themselves remain in exile, many of their children were repatriated thanks to the efforts of supporters in Japan. Following the arrests of members of the Japanese Red Army such as Shigenobu Fusako and Yoshimura Kazue, support group members and lawyers also helped negotiate so that their stateless children could be brought to Japan and cared for while their parents served their sentences. Not limited to political protestors, KRS has been involved with many criminal cases in which the convict has been allegedly wrongfully convicted.

2. Hoshino Defence Committee

The Hoshino Defence Committee is a tightly-knit lobby network of several support smaller groups around the country, organized through the main office based in Tokyo.

Hoshino Fumiaki is now in his sixties. He was arrested in 1975 for his suspected role in the death of a police officer during a Chūkaku-ha (Middle Core Faction) demonstration in Shibuya on November 14, 1971.

|

Youthful photo of Hoshino Fumiaki |

While many people were arrested on the day in connection with the overall demo (dubbed a riot by police), the police only began later to hunt for the people responsible for the death of the police officer. Hoshino and others went underground as several people were arrested and police narrowed their search to Hoshino. He was eventually apprehended and charged in relation to the death. With testimony based on the apparent confessions of five other participants – statements subsequently retracted or denied – the prosecution sought the death penalty for Hoshino. (This was at a time when several other prominent New Left trials were taking place, and the authorities were likely seeking to set an example.)

Supporters rallied behind a petition signed by 120,000 against this, as a means of building popular support against execution. In the end, Hoshino was found guilty in 1979, but was sentenced to 20 years. This was appealed (by the prosecution) and in 1983 his second trial ended with a life sentence. Hoshino immediately wanted to campaign for a retrial.

Hoshino had been supported by another group from the 1970’s to the early 1990’s campaigning for three of the activists connected with the case. The supporters then began to lobby focussed on his individual campaign. In 1988 the first groups were established in Suginami in west Tokyo and in Tokushima, the prefecture on Shikoku where Hoshino was serving his sentence. In 1994, a “return Hoshino group” was formed in Okinawa, the prefecture for whose emancipation he had originally protested. And then in 1996, the Hoshino Defence Committee was established to consolidate the work of the three groups. Following this, other groups sprang up in Hokkaido (Hoshino’s home region), Yamagata and elsewhere. There are at the time of writing 26 groups around Japan, with the most recent being formed in Iwate this January.

The groups have slightly varying names, which reflect the nuances emphasized by each. For example, some use the word “return” (torimodosu), while others “save” (sukuu) or emphasize “solidarity with” (rentai suru) depending on their preferences. The central aims, though, are the same: to raise awareness and funds for Hoshino’s retrial application.

The application has been rejected twice but the Hoshino Defence Committee has lodged an objection to the second rejection, and the decision on this is currently pending. The Committee is also pursuing two civil suits and requesting that all evidence be made public (in Japanese trials, prosecution evidence may be concealed), as well as demanding improved conditions in Tokushima Prison, where there is no heating or air-conditioning.

|

Sketch of Hoshima |

The first edition of the groups’ newsletter, the Hoshino Retrial News, was published in February 1996 and is now a monthly media usually around eight pages long. The Hoshino Defence Committee has had a modest office in Shimbashi since 1996 in the same building as the KRS office. The two networks work together and Hoshino’s case is also covered regularly in the KRS newspaper.

According to the Committee, there are around 1,000 supporters or members in the network, including its lawyers. The Committee’s office is staffed by four main volunteers, three of whom are assigned to the campaign while one assists the lawyers. The regional groups are mostly staffed by one or two volunteers, though some groups are run by single individuals. Rallies are organized through the network and other affiliated groups, which can mobilize several hundred people for key demos. At the moment, a major demo is held once or twice a year, though the regional groups or national committee also participate regularly in other leftist demos. As part of this they produce flags, sashes, badges and other items to advertise their cause. The network is international as well, making contact with other lobby groups and political campaigners around the world.

The members of the groups include hard-core, veteran political campaigners, as well as those who have joined the Hoshino cause later. It is led by Hoshino’s wife, Akiko, whom he married from behind bars, together with a man who was a fellow activist alongside Hoshino during the 1970’s. Hoshino’s relatives have been prominent but others have come to the network from backgrounds unconnected either to him or the 1960’s and 1970’s New Left. Some members are involved with other political campaigns.

There is rarely a month when there isn’t at least a talk or other event for members to attend. Hoshino is an avid painter and his supporters regularly hold exhibitions of his work around the country. Besides the legal activities – assisting the lawyers in the application for retrial, helping research into new evidence, and pursuing a civil suit over prison conditions – the Hoshino Defence Committee is busy providing updates via its newsletters and publishing Hoshino’s letters, as well as producing DVDs and merchandise such as pens and calendars. It even released a book on the case last year.

|

Love and Revolution . . . the book on the Hoshino case |

It openly publishes information on its budget and expenditure, as is common in support groups, and makes requests for donations for legal fees.

Police presence at the Hoshino demos is always very high. A large contingent of security police will photograph and monitor the participants and what is said, as is standard practice for any New Left protest in Japan. The prison authorities have also heavily censored letters between Hoshino and his wife, Akiko. How, then, do the supporters maintain motivation over such a long time as legal proceedings stretch out so slowly between court decisions? Undoubtedly Akiko’s visits to Hoshino play a large role here, not only giving him a window to the outside world but also providing supporters with updates on his thinking and state of mind. While he has suffered from illnesses due to his lengthy confinement, his frequent messages published in the newsletter remain positive and determined.

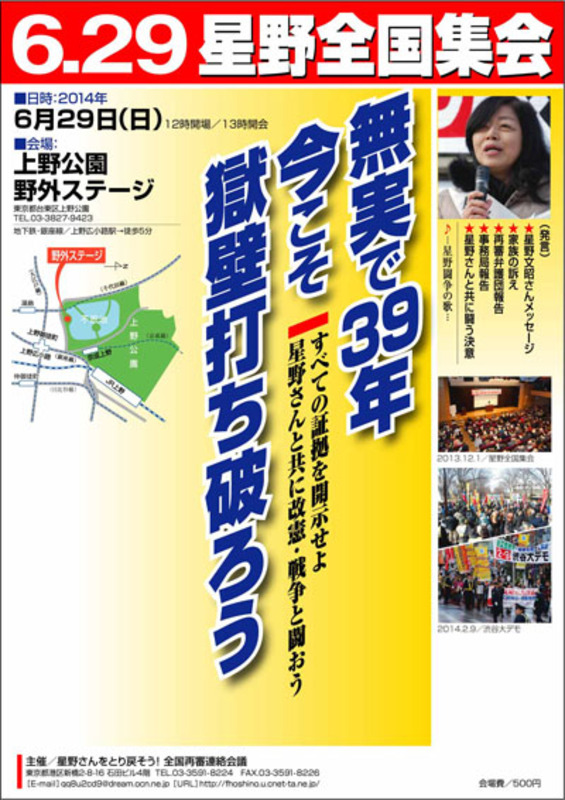

|

2013 Hoshino support demonstration |

The groups are also undeniably social; the people know and like each other. They are mostly the same generation and ironically, their treatment by the police makes them more hardened, resolute and tighter as a unit. (This is similar to what sociologists call labelling theory, where a “labelled” group will adopt the traits and role it is given.) And being of a certain age, they are now mostly retired and can afford to give more time to volunteering and activism. Regular demos and events mean a busy calendar; there is always the next thing to look towards. They are also constantly inventive and engaged in new projects. Having published a comprehensive book in 2013, they are now hoping to make a song for their campaign.

The people I have met and interacted with in the lobby group are certainly cynical about the government and the police, but they never seem to display doubt about whether they will succeed or fear their campaign is in vain. They are angry about Hoshino’s treatment and fiercely opposed to policies of the Japanese state and establishment, including but not limited to the case. Far from being resigned, they view every small victory or news tiding as a confirmation that things are moving towards their ultimate goal. (The recent releases of Hakamada Iwao and the American lawyer Lynne Stewart are two examples.) In this more cynical age, their hope and indefatigable energy are at times quite surprising, though also a reminder of the mindset required to continue activism in the face of such legal and social obstacles.

|

Poster for forthcoming June 29 demonstration to free Hoshino |

3. Challenges for Grassroots Activism

Judicial reform is still badly needed in Japan. Lawyers are not present during police interrogations, nor are these fully recorded. Since trials are so long and the system weighted against the suspect, most people give up even if they are innocent as the ordeal to fight is too hard. The options at the disposal of the defendant are so meagre there have even been cases of lawyers and defendants refusing to attend court sessions in protest at prison treatment. Due to restrictions on visiting rights, prisoners may be forced to legally adopt supporters or let themselves be adopted in order to receive visitors. Death row visitor restrictions were partially improved in 2007, though in 2009 Amnesty International published a damning report indicating that Japan’s death row conditions breed insanity. The closed world of Japan’s judges has also recently been criticized by Segi Hiroshi, a former member of the profession, in his book Zetsubo no Saibansho (Courts without Hope).

In such a system, can grassroots lobbying make a real difference? It is often said that there is a dearth of grassroots political activism in Japan. While this may seem the case to the outsider, a closer examination reveals it is patently untrue.

From the Suginami housewives who collected 32.3 million signatures for Japan’s first Ban-the-Bomb petition in the 1950’s to the large participation of civic groups in the 1960 Anpo movement, the anti-Vietnam War group Beheiren, and the Heisei-era campaign that led to the Freedom of Information Law in 2001, there are many well-known examples of local, low-level activism and national protests on environment issues, US bases, and more.

The story of Heisei Japan is not only the economic basket case one, as the western media might have us believe; it is also one of a rising civil society, with increased numbers of volunteers and civic groups. Jeff Kingston memorably calls this “Japan’s quiet transformation” and it is perhaps typified by the nation’s three-fold increase in volunteers between the 1980’s and the turn of the century. Over a million volunteers assisted in the recovery operation for the 1995 Kobe earthquake and the large numbers of volunteers who helped after the Tōhoku disaster showed how established the mindset has become. Carl Cassegård also recently published a book, Youth Movements, Trauma and Alternative Space in Contemporary Japan, documenting in detail the rise of freeter activism and independent unions supporting the rights of the precariat.

Through KRS and other political support groups, thousands have had experience of legal and organizational grassroots lobbying from the 1970’s onwards, supporting an individual to mount a political challenge to the state – one which is often long in gestation and requiring great tenacity to maintain. While difficult to quantify, it is not too much to suggest this contributed to the later flowering of civil society in Heisei era.

There have been some success stories. Hakamada Iwao was recently released and no doubt his sister’s unflagging support, along with groups like KRS and the Japan Pro Boxing Association, helped keep his case in the public eye. Likewise, notorious cases of wrongful conviction such as Sugiyama Iwao and Sakurai Shōji (the Fukawa Incident), Govinda Prasad Mainali and Sugaya Toshikazu eventually saw justice served.

By and large, though, these have been criminal cases. When politics is involved, such as is the case with Hoshino Fumiaki, getting a retrial is arguably only a pipe dream pursued out of dedication and a sense of righteousness. Hoshino recently had some of his prison privileges increased, but it is hard to judge if the campaigning contributed to this or it was just a matter of good behaviour and the length of his sentence served. In fact, a convicted prisoner may have his or her visiting rights restricted if they pursue further legal action.

Many people give up even if they know they are innocent since the ordeal of fighting is too arduous. When the case is clearly a “frame-up” or where the evidence has been tampered with – such as allegedly is in the Hakamada case – the mainstream media will also take more of an interest. However, for every Hakamada there are many who did not succeed. Kuma Michitoshi was executed in 2008 at the age of 70, though posthumous efforts continue to have him exonerated over allegedly doctored DNA tests. Kuma’s case would have proven another great stimulus for judicial reform, but the request for a retrial was thrown out.

To the chagrin of the support groups, scandals like the Hakamada case are not leading to apologies or improvements in the system. On the contrary, the police and prosecution are trying to change things to suit their will. For example, the campaign to introduce full video-taping of interrogations has so far not succeeded.

For all their efforts, the groups remain small and limited. With the exception of an overall umbrella network like KRS, the groups are intimately connected to individual cases, which can have the effect of overly localizing their aims. Similar to the abundance of small-scale NPOs (Non-Profit Organizations) in Japan, these support groups are further examples of how social movements often fail to mobilize effectively on a national or international level. More support groups and human rights organizations are needed, especially larger ones.

KRS is not a legal entity. It has never received recognition or support from the government since it started, not least because it continues to support anti-government activists (from the East Asia Anti-Japanese Armed Front group to Sekigun-ha, Hosei University protestors and others) and to campaign against the death penalty. Even Amnesty International’s Japan branch faced an uphill struggle to achieve legal recognition. The NPO, a triumph of Heisei Japan, is prevented legally from being political, so this leaves no option for the lobby groups but to exist outside the system. If they then only handle money as donations and everyone works as a volunteer, this does not create issues with the tax authorities.

However, KRS and its lawyers cannot take on every case, and there is an urgent need to increase the number of lawyers and volunteers working within its network and beyond. “We are also unsure how to improve the situation,” one of the KRS staff says. “We have to get young people interested but they have enough troubles in their daily lives right now. Political activism itself has to increase.” When there is heightened interest in a political issue, groups like KRS are more successful in campaigning for funds and the cases they represent.

Today the Kyūen Renraku Sentā has a team of four, plus an office manager. They have around 100 lawyers in Tokyo in their network, along with others around the country. It still issues cards providing contact information as it did at the height of the New Left protest cycle, though now more to anti-nuclear power protestors who may have no experience of demonstrating and the dangers of arrest. They continue to make their telephone number and advice available. In this way, their core activities haven’t changed much – providing legal support and offering advice for defendants should they be arrested. They still produce a booklet which they are able to give to people if arrested. One major change, though, is that they are contacted more frequently via the Internet now.

Times have moved on, then, but some things remain the same. Late last year a 45-year-old man from Shizuoka travelled up to Tokyo by himself to protest the state secrecy law. Iwahashi Kenichi was not a particularly political person but he felt inspired by the demonstrations. One thing led to another and he ultimately took off his shoes and threw them in the chamber of the House of Councillors to protest the controversial law. He was held in detention for 84 days. KRS stepped in to help him, an example of how it continues to play a role in contemporary cases.

The New Left support groups represent part of what Patricia G Steinhoff calls Japan’s “invisible civil society”. It is a loose network of former New Left activists who maintain their connections with protest in legal ways following the police crack-down that contributed to the decimation of mass left-wing protest movements in previous decades. The cruel way of looking at this is to call them naive veterans still clinging to utopian dreams. The more positive interpretation is to think of them as honourable and sincere activists still seeking ways to improve society in the face of hardships they and others have faced.

William Andrews is a Tokyo-based writer, translator and editor. He writes and researches about post-war politics and counterculture in Japan, as well as performance and theatre. He is currently working on a book on Japanese radicalism. The ideas explored in this article are based on the author’s observations of the Hoshino Defence Committee, as well as an interview with Kyūen Renraku Sentā and reading from a range of materials.

Extensive field research on Japanese trial support groups in the context of the New Left has been previously conducted by Professor Patricia G. Steinhoff (University of Hawaii), from whose papers this article also draws.

Recommended citation: William Andrews, “Trial Support Groups Lobby for Japanese Prisoner Rights. The Long Fight to Rectify Injustices,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 21, No. 2, May 25, 2014.

Resources and Further Reading:

Andrews, William, “Wife fights decades-long battle to free Shibuya riot leader Hoshino”, Japan Times, November 18, 2013

Hoshino Defence Committee, “Ai to kakumei” (Love and Revolution) [2013]

Kyūen Renraku Sentā (Relief Liaison Center, or Kyuen Renraku Center):

http://qc.sanpal.co.jp/

Steinhoff, Patricia G, “Doing the Defendant’s Laundry: Support Groups as Social Movement Organizations in Japan”, Japanstudien, Volume 11 [1999]

Steinhoff, Patricia G; Zwerman, Gilda, “The Remains of the Movement: The Role of Legal Support Networks in Leaving Violence While Sustaining Movement Identity”, Mobilization, Journal 17 [2012]

Steinhoff, Patricia G, “No Helmets in Court, No T-Shirts on Death Row: New Left Trial Support Groups”, in “Going to Court to Change Japan: Social Movements and the Law in Contemporary Japan”, edited by Patricia G Steinhoff (University of Michigan Press) [2014] (forthcoming)

Related subjects

• Philip Brasor, Japan’s Lay Judge System and the Kijima Kanae Murder Trial

• David T. Johnson, Covering Capital Punishment: Murder Trials and the Media in Japan

• Jeff Kingston, Justice on Trial: Japanese Prosecutors Under Fire

• David T. Johnson and Franklin E. Zimring, Death Penalty Lessons from Asia