Précis

A near perfect storm has descended on Australian relations with its nominal strategic partner and largest neighbour, Indonesia, to the point where the Indonesian foreign minister, standing beside John Kerry in Jakarta, said it was “very simple.” “Australia must decide if Indonesia is a friend or an enemy.”1

|

Kerry and Natalgawa |

Courtesy of Edward Snowden, the Australian government is discovering that an asymmetry in electronic surveillance capacity does not trump the fundamental asymmetry of power between Australia and Indonesia, which geography, population size and importance in world affairs tilts in Indonesia’s favour. NSA documents that the premier Australian intelligence agency monitored and intercepted phone calls by the Indonesian president, his wife, and inner circle of advisors has generated a rapid collapse in relations between the two governments, possibly with long-term effects. The Indonesian government has called for a new intelligence accord, which will prove difficult for the Abbott government, not least because of the role of the NSA in Australian signals intelligence. A review of supervision and oversight of Australian intelligence agencies is urgently required.”

The revelation from the Snowden trove of National Security Agency documents, that the premier Australian intelligence agency monitored and intercepted phone calls by the Indonesian president, his wife, and inner circle of advisors, has revealed a great deal about the technical capacities of the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD; formerly the Defence Signals Directorate) – and of its managing partner in Five Eyes global intelligence collaboration, the NSA.

Moreover it has laid bare the lack of appropriate political and strategic supervision of ASD’s activities: what strategic interest could conceivably have been in the minds of the senior members of the ASD, the Australian Defence Force, the Department of Defence, and the Defence Minister himself when, according to the Australian government, all of these entities decided to engage in covert electronic surveillance of the most reformist and pro-Western group of Indonesian leaders in a generation? While there is nothing new in the revelations of Australian electronic spying on Indonesia going back to the 1960s and Confrontation under Sukarno, a decade and a half after the collapse of the Suharto dictatorship, the Indonesian withdrawal for East Timor, and the democratization, albeit uneven, of Indonesian politics, and after the declaration of a strategic partnership between Australia and Indonesia, ASD’s choice of targets was, as the Indonesian foreign minister later said, with almost English understatement, “a little bit mind-boggling”.

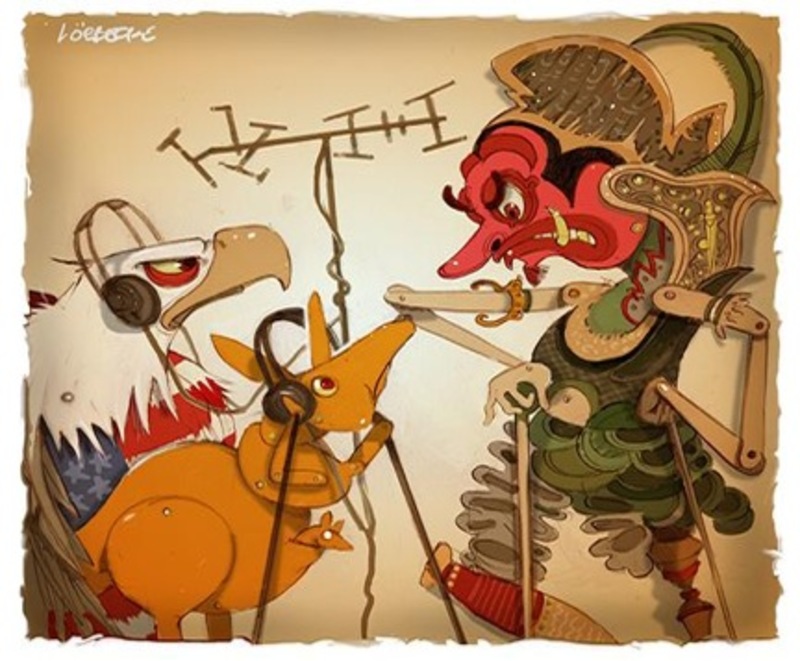

|

Löebkke on the Indonesian-Australian faceoff |

Yet the most significant results are still unfolding. Firstly, the realisation in the minds of at least some Australian senior political figures of a fundamental reality of Australia’s strategic situation that most have managed to deny for decades: that the relationship with Indonesia is fundamentally asymmetrical, and that in security terms Australia needs Indonesia a great deal more than Indonesia needs Australia. Secondly, that as a result of two unforced errors by the Australian government, it has handed Indonesia a lien on what Australia has long taken to be the most important military advantage it has held over Indonesia – the extraordinary signals intelligence collection capacities through which ASD provides Australian governments with comprehensive knowledge of any electronic transmission in the Indonesian ether – whether military, government, terrorist, or commercial. Thirdly, the SBY spying affair, as it has come to be called, has given rise to a much deeper fracture in the already volatile and brittle relationship between the two governments, a cleavage, sometimes evident, sometimes covered, that will persist long after the current Indonesian suspension of military relations and cooperation over border policing is resolved.i

The story breaks

How did all this come to pass? The story broke in three stages in October and November 2013.

First, on October 27, the German daily Der Spiegel published a 2010 NSA Powerpoint slide released by Snowden documenting the activities of NSA Special Collection Service (SCS) units or Communications System Support Groups (CSSG) operating under diplomatic cover from within US embassies in Berlin and elsewhere, under a program code-named STATEROOM, with a capacity to monitor “microwave, Wi-Fi, WiMAX, GSM, CDMA, and satellite signals.”ii While electronic spying from embassies, which is illegal unless approved by the host government, has been widely known to be taking place since the beginning of the Cold War by all concerned, including Australia, the Spiegel documents demonstrated that the STATEROOM program not only involved Australian embassies, but that data intercepted by STATEROOM in Australian embassies was automatically shared with the NSA.iii

It has long been known that ASD has conducted electronic interception out of its embassies, most importantly in Jakarta, under a program code-named REPRIEVE, since at least the 1970s and most likely much earlier.iv Three days after the Spiegel STATEROOM document release, Philip Dorling reported in Fairfax Media that ASD electronic interception operations are conducted not only out of the Jakarta and Bangkok embassies, but also from the embassy in Dili in Timor Leste and the consulate in Denpasar, Bali.v This would not have been news to the Indonesian government, although the confirmation of cooperation between DSD and the NSA was troubling, and Indonesia called in the Australian ambassador to ask, as Marty Natalegawa, the Foreign Minister, put it,

“If Australia was itself subjected to such an activity do you consider it as being a friendly act or not?’

The second part of the story, with more troubling implications for Indonesia and its relations with Australia came a week after the Spiegel STATEROOM document release.

On November 3 The Guardian wrote that another document in the Snowden trove revealed that

“Australian spy agency the Defence Signals Directorate worked alongside America’s National Security Agency in mounting a massive surveillance operation on Indonesia during the United Nations climate change conference in Bali in 2007.”vi

Beyond the issue of trust broached earlier in the week by Natalegawa, this document raised questions for Australians of what DSD and the NSA thought they were doing during new Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s first major international activity, in a country with which Rudd had declared he wanted closer relations, and whose cooperation on climate change policy would be critical in his plans for an Emissions Trading Scheme. Even for hard-line realists, this was an indication that something was awry in DSD tasking and risk assessment.

The third and most damaging revelation came two weeks later, when on November 18 the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and The Guardian Australia released a set of six more documents from the Snowden collection.vii This time, while the documents were downloaded by Snowden from the NSA, they consisted of six PPT slides produced by its Australian partner, DSD, explaining its achievements in monitoring and intercepting 3G cell phone communications amongst ‘Indonesian leadership targets’, apparently commencing in ‘2nd quarter 2007′.viii Stunningly, the slide listed the top ten targets and their phone types, starting with President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono; his wife; Vice-President Boediono; the preceding Vice-President Yusuf Kalla; and six of Yudhoyono’s most senior ministers and closest advisors.ix Other slides portrayed ‘intercepts events’ of Yudhoyono’s phone, and made clear that this was a model DSD was keen to apply elsewhere.

Then, in February of this year, when it had appeared that matters could not get worse for Australia, another tranche of Snowden documents released by the New York Times revealed that

- in 2012 Australia accessed “bulk call data” carried by satellite by one of the biggest Indonesian telecom companies , including communications within Indonesian government departments;

- in 2013 ASD acquired nearly 1.8 million encrypted master keys which protect the privacy of calls on another major Indonesian telecom network, together with the means to decrypt the calls; and

- in early 2013 offered to share with the NSA communications intercepted by ASD between the Indonesian government and a US legal firm representing Indonesia in trade negotiations with the United States.2

These four Snowden document revelations set the scene for an extraordinarily rapid collapse in Australian relations with Indonesia, a collapse almost entirely of Australia’s own making.

Firstly, the DSD slides became available to the NSA because DSD was simply boasting of its achievements. As former Assistant Defence Secretary Alan Behm noted,

‘It’s saying, “Hey look how clever we are”, and, “We’ve got all this”,” Behm said. ‘That’s juvenile cockiness. What was the purpose of writing it down? Was it to impress somebody?’

The second Australian unforced error came with the response of Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who abjured the tactic that Barack Obama had taken when the United States found itself in the same position with German Chancellor Angela Merkel – be proactive, fess up, apologize, and promise to not do it again. Rather, Abbott said that his government would follow ‘normal practice’ and not comment on intelligence matters. The matter might have rested there, albeit uneasily, since Indonesia had not asked for an apology. Except that Abbott went on to say that:

‘Australia should not be expected to apologise for the steps we take to protect our country now or in the past, any more than other governments should be expected to apologise for the similar steps that they have taken. … Importantly, in Australia’s case, we use all our resources, including information, to help our friends and allies – not to harm them.’x

Not unreasonably, Indonesians could well have wondered which category they were in, and in what way this was meant to help them. Abbott then managed to make things worse still by expressing his ‘deep and sincere regret about the embarrassment to the President and to Indonesia that’s been caused by recent media reporting’ – as if that was the most salient problem.xi

Over the next week everything went downhill for Australia, with Yudhoyono tweeting his anger, furious outbursts in the Indonesian parliament and the media, well-publicised protests in the streets of Jakarta – albeit mostly from the disturbing conflict entrepreneurs of the Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pemebela Islam). The Indonesian policy response was swift and deeply damaging to Australia – withdrawing its ambassador from Canberra, and cutting off of all military cooperation, military exercises, intelligence sharing, and police and maritime cooperation regarding Australian border and immigration controls (aka ‘people smuggling’). This was capped off by a demand from Yudhoyono that Australia reach ‘a new intelligence accord’ with Indonesia.

In February, after declaring the revelations of the trade negotiations intercepts, “a little bit mind-boggling”, Natalegawa changed tack, and decided to make clear to the US that if it wanted, in the language of the November 2010 United States-Indonesia Comprehensive Partnership agreement “to enhance cooperation between the world’s second and third largest democracies”, then the US needed to bring its Australian partner to heel. Standing next to John Kerry, Foreign Minister Natalegawa said it was “very simple.” “Australia must decide if Indonesia is a friend or an enemy.”3

The fallout – intelligence, strategy, culture, and power

The Abbott government has no choice but to agree to such a request, but will have every reason to make sure that any intelligence commitments made are unenforceable and hollow. This is partly because the REPRIEVE operation, and its STATEROOM components in association with the NSA, make up only a small part of the extraordinarily effective Australian capacity to intercept virtually all Indonesian cell phone, radio, microwave and satellite communications. While the Jakarta embassy operation is itself very productive, its capacities are dwarfed by the satellite communications interception capacities of the Shoal Bay Receiving Station in Darwin.

|

Shoal Bay Receiving Station, January 2013 Photo: Allan Laurence, Grey Albatross, Flickr [Source] |

Since its establishment in 1974, Shoal Bay’s large parabolic antennas have focussed on Indonesia’s communications satellites (and those of many other countries) hanging over the equator in geo-stationary orbit above Southeast Asia. Shoal Bay listened to the orders given by Indonesian army officers to execute five Australian journalists captured in the preliminary invasion of East Timor in October 1975.xii Through Shoal Bay, the Australian government was given complete information on the activities of the Indonesian army and its Timorese militia clients in their planning of the terror in the lead-up to the 1999 UN-auspiced Timorese vote for self-determination.xiii Today, there can be little doubt that ASD, through Shoal Bay in particular, but also possibly through other platforms, has a very complete picture of the military, political and economic activities of the Indonesian army – and those of its special forces, Kopassus in particular, with its appalling record of ongoing human rights abuses – in the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua (Papua Barat).

While all Indonesian governments for almost four decades have known the functions of Shoal Bay at a general level, it is a very different matter for Indonesian military and government communications security specialists to be sure of exactly what the facility can and cannot do technically. The Australian government will be very anxious to protect that uncertainty. And the same is true of any acknowledgement of the REPRIEVE or STATEROOM operations.

Little is known of the precise contents of current intelligence accords, which under a wide range of agreements signed between the two countries since 2000, concentrate on shared concerns about counter-terrorism and the Australian preoccupation with border maintenance activities at sea and disrupting people smuggling activities within Indonesia (Table 1). What Indonesia will be asking for in the new round of negotiations is unclear, but it will certainly seek to take the 2006 Framework Agreement on Security Cooperation Agreement (Lombok Agreement) a great deal further. In negotiations over that agreement, Indonesia persuaded the Australian government to guarantee to inhibit support for any threat to the territorial integrity of Indonesia – effectively requiring the Australian government to restrict civil society activities in support of West Papuan self-determination.xiv While there may be a temptation to tear up the Lombok Agreement – as Jakarta did in late 1999 when it rescinded the 1995 Australia-Indonesia Security Agreement – it is more likely that it will leverage more access to, and at least a degree of nominal control over, Australian electronic intelligence aimed at Indonesia.4

Table 1: Australia-Indonesia political, military, intelligence, policing, and border maintenance agreements, 2000 – 2012

|

2000/10 |

Signing of MOU on Legal Cooperation |

|

2002/2 |

Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime established (Australia and Indonesia co-chairs) |

|

2002/2 |

Signing of MOU on Terrorism |

|

2002/6 |

Signing of MOU Combating Transnational Crime and Developing Police Cooperation |

|

2002/6 |

Renewal of MOU between the Australian Federal Police and the Indonesian National Police |

|

2002/9 |

Signing of protocol between the AFP and INP to target people smuggling syndicates operating out of Indonesia |

|

2005/1 |

Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Reconstruction and Development (AIPRD) |

|

2006/10 |

Signing of Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Migration and Border Control Management |

|

2006/11 |

Signing of Agreement Between the Republic of Indonesia and Australia on the Framework for Security Cooperation (Lombok Treaty) |

|

2008 |

Australia Indonesia Partnership Strategy |

|

2008/8 |

Implementation of Border Management Capacity Building Partnership through Enhanced CEKAL Border Alert System |

|

2008/11 |

Announcement of Australia-Indonesia Facility for Disaster Reduction |

|

2008/11 |

Joint Statement on People Smuggling and Trafficking in Persons |

|

2012/9 |

Defence Cooperation Arrangement |

Moreover, if the question of the operations, capacities and sharing of products of Australian signals intelligence is to be discussed with Indonesia, the United States is immediately a third party in the room. The STATEROOM and other Snowden documents have made clear that ASD’s signals intelligence operations are integrated with those of the NSA and the CIA at levels far deeper than in previous decades. This in itself limits just how conciliatory Australia can be towards Indonesia.

Most importantly, in July 2013, Philip Dorling revealed in Fairfax Media that four ASD facilities are involved in a United States global signals intelligence and internet intercept collection analysis program code-named X-KEYSCORE.xv In addition to Shoal Bay Receiving Station, these include the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap outside Alice Springs, the Australian Defence Satellite Communications Station at Kojarena, near Geraldton in Western Australia, and HMAS Harman Naval Communication Station in Canberra. All of these facilities have expanded considerably in recent years, and all are closely connected with US intelligence or military operations.xvi That web of technical, legal, and organisational relationships will complicate discussions between Australia and Indonesia on a new intelligence accord.

There are three further consequences of the Yudhoyono spying affair for Australia, beyond whatever eventuates from the intelligence accord negotiations. The first is the realisation that Australia’s defence preoccupation vis-à-vis Indonesia with maintaining ‘a technological edge’ over its neighbour’s military and intelligence capacities comes at a price which is substantially political in nature, at least in the intelligence area. The intelligence security failings of Australia’s alliance partner the United States have led to part of that price being exacted, at least for now. Australian security elites value the technological benefits of close alliance with the United States while minimizing the costs – in some cases a matter of political and military dependence, and in other cases, as here, a matter of political embarrassment and more. A US alliance-derived asymmetry of military and intelligence capacities between Australia and Indonesia does not automatically translate into enduring strategic advantage for Australia.

The second aspect, which has been largely neglected in Australia, but understandably more attended to in Indonesia, has been the cultural dimensions of the affair, and what it has revealed about the deep structure of Australia’s most important foreign relationship, apart from that with the United States. In the lead-up to the spying affair, the dynamics of Australian electoral politics had driven the leadership of both major political parties to claim that the Australian-Indonesian relationship was the country’s most important, and that both countries were confident of the depth and quality of the understanding between them. At the same time, however, both of Australia’s major parties in fact treated the relationship in an openly instrumental manner, concerned only with what Indonesia could contribute to assuaging the moral panic and driving election campaign issue of ‘stopping the boats’ which were bringing a relatively small number of asylum-seekers from their way-stations in West Java towards Australia. Successive Australian governments have depicted these boat arrivals as would-be economic migrants, but in fact the great majority of asylum-seekers have been found to be genuine political refugees – “facing a well-founded fear of persecution” in their own countries – under the 1951 Refugee Convention, to which Australia (though not Indonesia) is a party.xvii

During the election the opposition immigration spokesperson, Scott Morrison, asserted that despite indications to the contrary, the Indonesian government would accept a Liberal policy proposal to “stop the boats”, including the proposal that Australia pay Indonesians to inform on each other about people-smuggling, and a bizarre scheme for Australia to buy up large numbers of decrepit Indonesian fishing boats that might have been used to transport asylum-seekers to Australia. In fact, Indonesian officials such as the Foreign Minister, Marty Natalegawa, had been entirely serious in their earlier indications to Australia that they were unhappy with what they saw as Australian political figures’ unilateral approach to people smuggling. Once in the ministerial seat, Morrison found that Natalegawa’s pre-election warning that Indonesia would not accept asylum-seekers intercepted at sea by Australia being returned to Indonesia was precisely the Indonesian government’s position. It was ‘very frustrating’, Morrison said on 11 November, in the early stages of the spying affair, and he could see ‘no real rhyme or reason’ in some Indonesian actions.xviii

Morrison’s implicit suggestion that Indonesia was not being rational echoed an old trope in Australian politics of irrational Indonesians and rational Australians. Almost half a century ago, at the birth of the New Order, a leading Australian newspaper editorialised on Indonesians as ‘experts at double-talk’, for whom

‘it is too much to hope that the new Indonesian regime will be logical; our best hope is that it will be practical.’xix

On November 23, Paul Kelly, one of the most senior of Australian newspaper editors, responded to the likelihood of the Indonesian government weakening Australia’s regional position and ruining Abbott’s ‘stop the boats’ pledge in words that could have been written by his predecessor half a century ago:

‘A rational Indonesia would do none of this. So Abbott must encourage the forces of rationality in Jakarta.’xx

Condescension, ethnocentrism and an often racialised view of cultural differences are never far from the surface in Australian dealings with Asia. Kelly’s recommendation for Abbott to seek ‘the forces of rationality in Indonesia’ is one expression. Another was the view of Indonesia expressed on November 20 by the Liberal Party’s pollster and campaign strategist, Mark Textor, who in a tweet said of the Indonesian foreign minister,

‘Apology demanded from Australia by a bloke who looks like a 1970s Pilipino [sic] porn star and has ethics to match.’xxi

Described in one Australian ‘power index’ as No. 4 in the list of Spinners and Advisers, Textor has been described as

‘the suburban whisperer, a man able to conjure up what’s in the hearts and minds of ordinary Australians.’xxii

The sexualised insult in Textor’s remark may well have expressed what many Australians think about Indonesia at a deeper level, since power, race, and sexuality are usually more closely related than is considered polite to talk about in international relations. More than three-quarters of a million Australians visited Bali in 2011 – and very few to other parts of Indonesia.xxiii Despite this a Foreign Affairs Department survey revealed that 30% of Australians think that Bali is a country.xxiv Many Indonesians have very mixed feelings about the flood of foreign tourists, particularly Australians, to Bali – and in both countries, there is an association of Australians in Bali with sex.

Three days after Textor’s text, the Jakarta daily Rakyat Merdeka replied with a specially commissioned cartoon that depicted the Australian Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, in his trademark skimpy Speedo swimwear (known as ‘budgie-smugglers’ in Australian parlance)

‘as a peeping tom, cracking open a doorway marked “Indonesia” while apparently masturbating and exclaiming “Oh my God Indo … So Sexy.”‘xxv

|

Of course, like Textor’s tweet, the Indonesian cartoon was intentionally offensive and provocative, but probably just as revealing of at least one substantial strand of popular Indonesian attitudes to Australia. As with Textor whispering to the Australian suburbs, Rakyat Merdeka found a way to whisper to the kampong.

A leading Australian specialist of Indonesian politics, Richard Chauvel, has pointed out one cultural aspect of the manifold asymmetries between the two countries that may help explain why Indonesia is coming out on top of this affair, and why the Australian government has been consistently wrong-footed. In the senior Indonesian leadership there is now a cohort of officials who know Australia well, have lived here, and have well-founded and often complex views about the country – not always complimentary. Three key players in Indonesian foreign policy and opinion leaders in recent years who have been deeply involved in the dynamics of the affair are the Foreign Minister, Marty Natalegawa; the Vice-President, Boediono; and Boediono’s foreign policy adviser, Dewi Fortuna Anwar. All three earned their masters or doctoral degrees at Australian universities, and all three know Australian society very well. No doubt their knowledge of Australia has fed into the advice President Yudhoyono has received about how to play the cards dealt to Indonesia by Australia’s mistakes. The problem for Australia is that there are remarkably few senior Australian political or bureaucratic figures with anything like their knowledge of or direct experience in Indonesia.

The fundamental discovery – painful for the new government – is that, while on some measures, the two countries have grown a little closer in recent years, the fundamental relationship between Indonesia and Australia is an asymmetrical one. Indonesia is far more important to Australia’s security concerns than is Australia to Indonesia’s. However wounding the recognition may be to Australian narcissism, Australia is also much the less important in world affairs and world history in almost every respect, except through the size of its economy at this point in history – a distinction that is fading fast with Indonesia’s rapid economic growth.

As the anxious responses to the current breakdown in relations from Australian opinion leaders in government, trade, and defence made palpably clear, Australia has considerable interests and political problems (of which ‘border protection’ is the least important, though politically most significant) over which, the Indonesian government, even if it does not yet have veto power, has a capacity to grant – or withhold – essential cooperation.5

Realities in intelligence tasking and oversight

In all this, both sides claimed the other was motivated by domestic politics, and hence its claims should not be taken too seriously. Indonesian nationalism on one side, and Australian moral panic about ‘stopping the boats’ on the other, though in fact both were correct. Equally, Indonesian feigned ignorance of the endemic reality of intelligence surveillance of countries of interest – from embassies or military bases or other platforms – showed a sizeable degree of hypocrisy. And one of those countries of interest for Indonesian intelligence services in the past, and certainly today, is of course Australia. Yet, as with the German reaction to the Snowden revelations, the history of the damage caused by unfettered intelligence agencies, as evidenced by the Indonesian experience during the New Order, also explained a good deal of the Indonesian response.xxvi

From the Australian side, there are clearly strategically important tasks and targets for Australian intelligence, electronic and otherwise, in Indonesia today. The list begins with the standard military requirements for any and all neighbouring countries in peacetime – force structure, order of battle, bases, doctrines, personnel, staff structure, budgets, armed forces politics, and so on. In Indonesia’s case its Papuan provinces are a strategic concern because of the likely impact on Australia of any serious disturbances on Papua-New Guinea, and a moral concern to many Australians because of the appalling human rights situation in those provinces. For both reasons, as during the Timor colonial project, it is essential that Australian governments be fully informed of such activities by the Indonesian military.6 And at times of serious potential or actual policy disagreement or conflict, political intelligence on the thinking and policy directions of the Indonesian leadership is essential – with two caveats, neither of which appears to have been satisfied in the Yudhoyono case.

The first is that since intelligence is a policy tool rather an end in itself, there must always be an assessment of strategic advantage versus risk, including the risk of being caught out and the cost of the consequences. Behm’s remarks on the hubris that lay behind the boastful Powerpoint presentation are salient here.

But beyond that, there is a second condition that one would expect to be in play if a high risk operation is to be carried out, never mind boasted about in Powerpoint, and that is that the proposed operation meets a serious strategic or tactical requirement. This should be the most disturbing aspect of the affair for Australians: what possessed a Minister of Defence to sign off on the targeting of the leadership of the most pro-Australian Indonesian administration ever, at a time when the level of genuinely shared interests on issues such as climate change was becoming evident?7 (This presumably involved – if indeed the minister was involved – either the last of the Howard era Defence Ministers, Brendan Nelson, or the first of the Rudd years, Joel Fitzgibbon.)

The explanation – at a ministerial level or senior ADF level – finally must come down to one of three factors, none of them comforting for Australian political interests, and all of which point to an acute need for reform in the supervision and oversight of Australia’s rapidly growing intelligence services. One element, perhaps indicated by the hubris of the Powerpoint presentation, is simply ASD (then DSD) arrogance and over-confidence – because ASD could do it, and because it has performed extraordinarily well in technical terms for a long time, there was no reason to not do so.

A second possibility is that ASD’s tasking priorities did not register a change in the designation by successive governments of Australia’s relationship with Indonesia as one of formal strategic partnership after the Timor and Suharto years. With the normal assessments of neighbouring defence establishments and activities, ongoing problems caused by Kopassus operations in the Papuan provinces, a necessarily ongoing pattern of widespread electronic surveillance for counter-terrorism purposes, and perhaps, government pressure for ASD assistance to people-smuggling disruption operations, ASD would normally have a sizeable Indonesian task list. But none of that would lead to a requirement for deeply intrusive, high risk/low yield surveillance of the top leadership of a friendly country that has been more cooperative with Australia than has been good for its own political interests.

Though both of these point to a need for reform, a third possibility is more disturbing still: that ASD undertook these operations as part of a wider pattern of cooperation with its United States counterpart, and essentially at its request, either implicitly or explicitly. At this point little is known about any differences between Australian embassy operations over many years under the REPRIEVE program, and more recent operations, possibly different in character or direction under the US-led STATEROOM program. An implicit request may have been as simple as a global list of similar target categories in each country – say ‘3G cell phones of leadership groups’ – whatever the character of the government concerned or its relationship to the particular member of the Five Eyes coalition actually carrying out the surveillance. After all, US interests in Indonesia are likely to be differently conceived than those of Australia, and it is possible the habit of cooperation developed over many decades of DSD-NSA collaboration overrode any note of Australian caution. The enthusiastic hubris of the Powerpoint presentation, in the context of the broadening and deepening of ADF cooperation with the US more generally makes this somewhat plausible.

Absent an open inquiry, we may never know. But all three explanations point to an urgent need for much more serious ministerial supervision and parliamentary oversight of the Australian Signals Directorate. As many people have noted in the countries that have been the subject of revelations from the Snowden files to date, there is undoubtedly more to come, and more for Australians to learn about their out of control intelligence services.

This is an updated and expanded version of, “Indonesia, Australia and Edward Snowden: ambiguous and shifting asymmetries of power, Nautilus Institute, Special Report, 29 November 2013.

Recommended citation: Richard Tanter, “Indonesia, Australia and Edward Snowden: ambiguous and shifting asymmetries of power,” The Asia Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 10, No. 3, March 10, 2014.

Richard Tanter is Senior Research Associate at the Nautilus Institute and teaches in the School of Politics and Social Science at the University of Melbourne. A Japan Focus associate, he has written widely on Japanese, Indonesian and global security policy. He co-edited with Gerry Van Klinken and Desmond Ball, Masters of Terror: Indonesia’s Military and Violence in East Timor [second edition 2013]. Email: [email protected]

Home page: http://nautilus.org/network/associates/richard-tanter/publications/

Sources

i Nancy Viviani was the first to emphasise this often unrecognised power asymmetry in the relationship. See Richard Tanter, ‘Shared problems, shared interests: reframing Australia-Indonesia security relations’, in Jemma Purdey (ed.), Knowing Indonesia: Intersections of Self, Discipline and Nation, (Clayton: Monash University Press, 2012).

ii ‘Embassy Espionage: The NSA’s Secret Spy Hub in Berlin‘, Spiegel Online International, 27 October 2013; and ‘NSA hid spy equipment at embassies, consulates‘ AAP and Michael Lee, ZD Net, 31 October 2013. Earlier Snowden leaks had documented a range of NSA techniques of intercepting communications of some 38 embassies and consulates, including the EU delegation to the United Nations in New York. This included the DROPMIRE programme of implanting a bug in encrypted embassy fax machines, as well as taps into cables. ‘New NSA leaks show how US is bugging its European allies‘, Ewen MacAskill in Rio de Janeiro and Julian Borger, The Guardian, 1 July 2013; and ‘Attacks from America: NSA Spied on European Union Offices‘, Laura Poitras, Marcel Rosenbach, Fidelius Schmid and Holger Stark, Spiegel Online International, 29 June 2013.

iii Slides 5 and 6, ‘STATEROOM Guide‘, National Security Agency 2010, in ‘Photo Gallery: Spies in the Embassy’, Spiegel Online International, 27 October 2013.

iv Desmond Ball, Signals Intelligence in the Post-Cold War Era: Developments in the Asia-Pacific Region, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 1993, p. 68.

v ‘Exposed: Australia’s Asia spy network‘, Philip Dorling, Sydney Morning Herald, 31 October 2013.

vi ‘NSA: Australia and US used climate change conference to spy on Indonesia‘, Ewen MacAskill and Lenore Taylor, The Guardian, 3 November 2013.

vii ‘Australia spied on Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, leaked Edward Snowden documents reveal‘, Michael Brissenden, ABC News, 18 November 2013.

viii Slide 3, ‘Gallery: Leaked DSD documents reveal Australia’s attempts to spy on Indonesian president‘, ABC News, 18 November 2013.

ix ‘Who are the 10 Indonesians on Australian spies’ list?‘ Katie Silver, ABC News, 19 November 2013.

x Just between frenemies, Peter Hartcher, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 November 2013.

xi ‘Indonesia scuttles war on people smugglers as Prime Minister Tony Abbott refuses to back down on phone tapping‘, news.com.au, 20 November 2013.

xii Desmond Ball and Hamish McDonald, Death in Balibo, Lies in Canberra, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2000.

xiii Desmond Ball, ‘Silent Witness: Australian Intelligence and East Timor’, in Richard Tanter, Desmond Ball and Gerry Van Klinken (eds.), Masters of Terror: Indonesia’s Military and Violence in East Timor in 1999, (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, second edition, 2006).

xiv Article 2.3. ‘The Parties, consistent with their respective domestic laws and international obligations, shall not in any manner support or participate in activities by any person or entity which constitutes a threat to the stability, sovereignty or territorial integrity of the other Party, including by those who seek to use its territory for encouraging or committing such activities, including separatism, in the territory of the other Party;’

xv ‘Snowden reveals Australia’s links to US spy web‘, Philip Dorling, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 July 2013. See also the Wikipedia entries on X-KEYSCORE and other US and allied surveillance programs revealed by Edward Snowden: e.g. ‘XKeyscore‘, Wikipedia (retrieved 27 November 2013).

xvi See Richard Tanter, “The US military presence in Australia: asymmetrical alliance cooperation and its alternatives“, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 45, No. 1, 11 November 2013; Richard Tanter, The “Joint Facilities” revisited – Desmond Ball, democratic debate on security, and the human interest, Special Report, Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, 12 December 2012; and ‘Shoal Bay Receiving Station‘, Australian Defence Facilities, Nautilus Institute.

xvii Richard Tanter, ‘“The Papua-New Guinea Solution”: Competitive Cruelty and Strategic Folly‘, Nautilus Institute, NAPSNet Policy Forum, 6 August 2013.

xviii ‘Indonesia’s refusal to accept asylum boats ‘very frustrating’: Scott Morrison’, Jonathan Swan, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 November 2013.

xix Editorial, ‘Testing the winds, The Age, 14 April 1966. See also Richard Tanter, ‘The Great Killings in Indonesia through the Australian Mass Media’ / ‘Pembunuhan Massal di Indonesia dalam Tinjauan Media Massa Australia’, in Bernd Schaefer and Baskara T. Wardaya (eds.), 1965: Indonesia and the World / 1965 Indonesia dan Dunia, Jakarta: Kompas Gramedia, 2013, (bilingual edition).

xx ‘Concessions to Jakarta are Tony Abbott’s only way to respond‘, Paul Kelly, The Australian, 23 November 2013.

xxi ‘Mark Textor stokes fire with Indonesian Foreign Minister “porn star” gibe; sack him, says Malcolm Fraser‘, Mark Kenny, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 November 2013.

xxii ‘Textor turns tweeter again, to apologise‘, Tony Wright, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 November 2013.

xxiii ‘Is Bali a risk worth taking?‘, Clive Dorman, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 2012.

xxiv Australian attitudes towards Indonesia: A DFAT-commissioned Newspoll report, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, May 2013.

xxv ‘Abbott cartoonist recalled to ridicule PM‘, Sydney Morning Herald, November 24, 2013.

xxvi Richard Tanter, ‘The totalitarian ambition: the Indonesian intelligence and security apparatus’, in Arief Budiman (ed.), State and Soviet in Contemporary Indonesia, (Clayton: Victoria: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, 1991), pp. 215-288.

Notes

1 Aubrey Belford, “Jakarta sees chilly ties with Australia until Oct – Indonesian govt document“, Reuters (16 February 2014; and “Menlu RI: Australia harus tentukan jadi teman atau lawan Indonesia, [Indonesian foreign minister: Australia must decide if it is to be a friend or opponent of Indonesia]”, Kompas, 17 February 2014.

2 Philip Dorling, “Edward Snowden leak: Australia spied on Indonesian phones and data” Sydney Morning Herald, 17 February 2014, at; and Michael R. Gordon, “Indonesia Takes Aim at Australia Over Spying on Talks“, New York Times, 17 February 2014.

3 United States-Indonesia Comprehensive Partnership, Fact Sheet, Office of the Spokesperson, U.S. Department of States, 8 October 2013; Aubrey Belford, “Jakarta sees chilly ties with Australia until Oct – Indonesian govt document“, Reuters (16 February 2014); and “Menlu RI: Australia harus tentukan jadi teman atau lawan Indonesia, [Indonesian foreign minister: Australia must decide if it is to be a friend or opponent of Indonesia]”, Kompas, 17 February 2014.

4 Tanter, “Shared problems, shared interests”, op.cit.

5 Former Australian Secretary of Defence, Paul Barratt gives two telling and salient examples in his “Goodwill between countries matters” in John Menadue’s blog Pearls and Irritations, 26 February 2014.

6 For a recent review, see Gemima Harvey, “The human tragedy of West Papua“, The Diplomat, 15 January 2014.

7 See Richard Tanter, “Shared problems, shared interest”, op. cit. ; and Allan Behm, Climate Change and Security: The Test for Australia and Indonesia – Involvement or Indifference? APSNet Special Report 09-01S, (12 February 2009).