Compared to its Asian neighbours, Indonesia was late to join the so-called third wave of democratisation that began in southern Europe in the 1970s. After the fall of the authoritarian Suharto regime (1967-98) it successfully conducted free and fair elections in 1999, 2004 and 2009, becoming arguably the most politically free country in Southeast Asia.1 A burgeoning civil society and a relatively open media have helped consolidate democracy but tensions remain between Suharto’s legacy and the direction of Indonesia’s democratic transition. In particular, Suharto-era oligarchs remain dominant and the armed forces retain significant influence even though their power appears to have declined and is less absolute than in much of Southeast Asia. The pluralism of Indonesia’s national motto, Unity in Diversity, is also being jeopardised by the failure to safeguard religious minorities against attacks from hardline Islamists. Against this backdrop Indonesia will administer its fourth round of post-Suharto elections in 2014, with legislative polls in April, followed by direct presidential elections in July.

This year’s elections are a litmus test for Indonesia’s own democratic transition, which could signal either a generational change in government reinforcing democracy or the return of dictatorial or repressive forces to office. Of the confirmed candidates for the presidential elections, the voting public currently faces a stark choice between military protégés of Suharto or oligarchs who made their fortunes under his authoritarian rule. However, according to public opinion polls, the favourite to win the presidency is the current Governor of Jakarta, Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo, a non-establishment figure with a wide popular base. Whilst a Jokowi presidency would represent a clean break from the Suharto era, the party with which he is associated is adamant that it will only select its presidential candidate after the April legislative elections. Nevertheless, his populist and innovative approach to running the largest city in Southeast Asia has raised hopes among the electorate that Jokowi will also be able to reinvigorate the country’s stalled reform drive at the national level. Indeed, Indonesia’s first two direct presidential elections, in 2004 and 2009, were also won on a platform of political reform and clean government by retired general Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who will soon reach the end of his term limit. Pro-poor policies and the prosecution of high-profile corruption cases during his first term contributed heavily to his success in the parliamentary and presidential elections of 2009.2

Yudhoyono’s legitimacy was also boosted by a resources and consumer boom which delivered steady economic growth of nearly six per cent a year during his decade in office. An expansion of the middle class accompanied Indonesia overtaking Malaysia as the world’s biggest exporter of palm oil, Thailand as the top exporter of rubber, and Australia as the largest exporter of coal.3 High prices for these and other resource commodities, largely fed by demand from China, increased the legitimacy of Yudhoyono personally, enabling him to bring valuable stability to Indonesia amid global economic turbulence. However, the president’s personal approval ratings dipped during his second term as fuel subsidies were reduced and members of his own party became snared in corruption scandals. The pro-poor policies introduced prior to the 2009 parliamentary election were mostly temporary. Despite improvements, Indonesia was still ranked 114 out of 177 countries by Transparency International in its latest annual survey on corruption perceptions.4 Disenchantment with the slow pace of reform, disillusionment with money politics and the lacklustre performance of many elected officials is widely expected to result in falling voter turnouts in 2014, especially if Jokowi is not nominated as a presidential candidate. Foreign investors have also signalled their continuing frustration with a graft-ridden legal system, opaque government policies and the country’s creaking infrastructure.

Consolidating the gains made under Yudhoyono, a Jokowi victory could indicate a shift away from Suharto-era vested interests to a less-patrimonial style of politics and a new generation of leader. Regardless of outcome, Indonesia’s elections are among the most significant of 2014 given that it is the world’s third largest electoral democracy, an ongoing test case for the transition from authoritarian rule and a prominent model for democratic survival in multi-ethnic states. The significance of these factors is compounded by Indonesian aspirations to play a leadership role both among developing countries and in Southeast Asia, as the region’s biggest country and economy. Given the continuing instability in Thailand, the recent unrest in Cambodia and Myanmar’s delicate democratic transition, democratic consolidation or reversal in Indonesia would carry symbolic weight at a regional level. This article opens with a brief history of post-reformasi elections in Indonesia, followed by an overview of the main parties and candidates with a short analysis of political Islam. Thereafter it will consider the influence of the media and the military upon Indonesia’s continuing democratic transition.

Post-Reformasi Elections in Indonesia

Electoral reform in Indonesia marks the country’s biggest departure from the Suharto era. Whilst parliamentary and presidential elections did take place under Suharto’s so-called New Order they were heavily manipulated by the regime to ensure success for the president’s own electoral vehicle Golongan Karya, usually shortened to Golkar. Electoral rules in place between 1973 and 1998 permitted only two opposition parties to contest parliamentary elections, thus forcing the merger of the main opposition parties. The four largest Muslim parties became the United Development Party (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan, PPP), whilst five secular parties formed the Indonesian Democratic Party (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia, PDI). Criticism of government policy by the PPP and the PDI was not allowed and government approval was required for all campaign slogans. Every candidate from every party was screened by the regime and fully half of all members of the national parliament were directly appointed by Suharto. Only Golkar was allowed to canvass support below the district level through local government officials and regional military commanders, and all government employees were required to support Golkar.5 This gave the party a huge advantage over its rivals in mobilising across the archipelago, a situation that largely still persists in the more remote areas of the country. Golkar’s record in the post-Suharto reformasi era has been mixed. Whilst it has repeatedly attempted to reduce the pace and depth of reform it has also made some important contributions to Indonesia’s democratic transition since 1998. This apparent paradox has prompted one observer to note, “Just like Indonesian politics in general, Golkar too is an ambiguous amalgam of progressive reformism and conservative status quo attitudes.” 6

Presidential elections were also held every five years during the New Order but these merely rubber stamped Suharto’s re-selection. This remained the case during the March 1998 presidential election which unanimously selected him for another five year term which was due to end in 2003, by which time he was almost 82 years old. However, two months later Suharto was forced to resign amidst a deep economic crisis, violent mass protests and a loss of elite support. Vice president B.J. Habibie replaced his mentor and, in order to boost his own legitimacy, hurriedly announced parliamentary elections for the following year. By demonstrating his own reformist credentials he hoped to secure a full term as president in his own right. With the New Order restrictions lifted some 48 political parties contested the 1999 parliamentary elections. The president was still to be chosen by the upper house, the People’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, MPR), following the elections. However, Habibie withdrew his candidacy after his accountability report was rejected by the new parliament and his party Golkar subsequently threw its support behind Abdurrahman Wahid. Even though Wahid’s National Awakening Party (Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa, PKB) only placed third in the legislative elections, with less than 13 percent of the vote, he was also leader of the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a traditionalist Muslim body that is Indonesia’s largest civil society organisation. Wahid also proved adept at building the necessary alliances to become president, relegating Megawati Sukarnoputri, whose PDI-P (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, Indonesian Democratic Party – Struggle) had actually gained the most seats in the elections, to the position of vice president.

Wahid made a bright start as president in 1999, bringing a much more pluralistic approach to the office. He opened up democratic space in West Papua, began peace talks with the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM) and lifted the New Order restrictions on Chinese cultural expression. These attempts at peacebuilding, alongside efforts to reform the military, provoked resistance from the political elite and Wahid became mired in a corruption scandal. This provided the pretext for the MPR to impeach him on charges of graft and incompetence in July 1999, and Megawati assumed the presidency. Having convincingly won the 1999 parliamentary elections, Megawati’s elevation represented a triumph for democracy. Her party was widely perceived as the main opposition in the late New Order period, and Megawati herself is the daughter of Sukarno, Indonesia’s founding president who was ousted by Suharto in 1967. Despite bringing a measure of political stability to Indonesia, however, her conservative administration came to be seen as listless and lacklustre. In particular, Megawati showed little appetite for military reform, was perceived as soft on regional terrorism and appeared unwilling to tackle corruption. Nevertheless, important constitutional reforms were instituted during her stewardship, including the establishment of the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK) and the Constitutional Court, and the introduction of direct local elections. These institutions would be developed further during her successor’s presidency. In contrast to his predecessors Habibie, Wahid and Megawati, Yudhoyono vowed to lead the anti-corruption drive personally, and reaped the rewards at the ballot box.7

The next round of national elections took place in 2004, contested by 24 political parties, and constitutional reform meant that the parliament would now be fully elected, with no reserved seats for the military. The president was now also directly elected in separate polls after the new parliament had been formed. The elections of both 1999 and 2004 were conducted relatively cleanly, leading democracy advocacy group Freedom House to categorise Indonesia as a ‘free’ country in 2005 after adjusting its status to ‘partly free’ following Suharto’s fall. Meanwhile, Freedom House, which publishes annual reports that analyse the extent of civil liberties and political rights throughout the world, downgraded the status of Thailand and Philippines from ‘free’ to ‘partly free’ in 2006 and 2007 respectively, underscoring Indonesia’s progress in a regional context.8 It is also worth noting that Indonesia’s elections of 1999, 2004 and 2009 were concluded mostly peacefully, again in contrast to the experience of Thailand and the Philippines in the same period.

Further highlighting how free and fair Indonesian national elections have become is the fact that in the first direct presidential elections of 2004 Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was able to defeat incumbent Megawati. She enjoyed the support of the largest party in parliament but Yudhoyono was able to convert his personal popularity with voters into victory. Indeed, ruling governments lost both the 1999 and 2004 presidential elections, and Yudhoyono’s triumph in 2009 marked the first time since 1998 that a sitting president has been re-elected to the highest office. Yudhoyono initially gained a reputation as a progressive military reformer in the late Suharto period, and had enhanced his standing with cabinet posts under Wahid and Megawati. His high personal approval ratings as president also enabled his relatively new Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD) to become the largest party in parliament in 2009, overtaking Golkar and PDP-P. This clearly demonstrates that, unlike regional neighbours Singapore, Malaysia and Cambodia, Indonesia has an electoral system that has not been unduly manipulated to favour the ruling party.9 At the same time, the emergence of new parties such as Yudhoyono’s PD has not led to the collapse of other major parties, unlike in Thailand, the Philippines, South Korea and Japan where parties often disappear after contesting one or two elections.10 The five largest parties from Indonesia’s 1999 legislative elections were still represented in parliament after the 2009 elections (see table below), although the number of minor parties has ebbed and flowed. Some 38 national parties contested the 2009 legislative election but new rules have trimmed their number to 12 for this year’s April elections.

|

President Yudhoyono and his wife Kristiani vote during the 2009 parliamentary elections |

Another distinguishing feature of party politics in Indonesia which has likely contributed to this stabilisation has been the fact that political parties do not usually engage in robust ideological debates with one another. Whilst the lack of substantive issue-oriented political debate raises doubts about the quality of Indonesia’s democratic transition, it has enabled the country to avoid the political polarisation that has paralysed party politics in Thailand and elsewhere. Instead Indonesian politics have become increasingly personalistic since the introduction of direct presidential elections in 2004, and the implementation of similarly direct elections for provincial governors, mayors and district heads in 2005.11 This lack of ideological polarisation has enabled all governments since Wahid’s first cabinet of 1999 to be multi-party coalitions where power sharing appears to be the dominant mantra. Yudhoyono continued this trend in 2004 when naming his first United Indonesia Cabinet in which only the PDI-P of the established political parties was not represented. Thus, in the 2009 legislative elections these other parties were unable to effectively challenge Yudhoyono’s PD on policy differences. The president repeated this strategy for his second United Indonesia Cabinet, formed at the beginning of his second term, in which again the PDI-P was the only major party not represented.12

Parties and Candidates

Electoral rules first applied in 2004 specify that a political party, or a coalition of parties, must secure a minimum of 25 percent of the vote or 20 percent of the seats in the April legislative elections to select a candidate to contest the July presidential elections. To win the presidency therefore, a candidate must be skilled at building alliances with other parties. Whilst the Constitutional Court recently ruled that this threshold is unconstitutional, electoral changes will not come into force until the 2019 polls. The Court also decided that the present requirement for voters to first elect parliament followed by a president is also unconstitutional; meaning that from 2019 simultaneous polls will be held. It is anticipated that this ruling may increase the number of candidates seeking to attain the highest office since until now presidential hopefuls have needed to secure the backing of large political parties.

In the three elections since 1999 the largest political parties have been Golkar, Suharto’s former election vehicle, and the PDI-P, widely seen as the main opposition in the late Suharto period. The PDI-P won 33.74 percent of the vote in the 1999 legislative elections, with Golkar second on 20.46 percent. However, both parties have been in decline, with Golkar losing the strength it derived from the New Order’s military and bureaucratic apparatus and the PDI-P failing to develop its reputation as the standard bearer of populist, secular nationalism. Since its founding in 2001 a new electoral force in Indonesian politics has emerged, that of Yudhoyono’s election vehicle PD. In addition to Golkar and the PDI-P, support for other established political parties has also declined, especially the PKB of former president Wahid and the venerable PPP (third and fourth respectively in the 1999 elections). Following the template successfully implemented by Yudhoyono’s PD, two other election vehicles for Suharto-era generals have also emerged since 2004. They are Gerindra (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, Great Indonesia Movement Party) under the leadership of Prabowo Subianto and Wiranto’s Hanura (Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat, Partai Hanura or People’s Conscience Party). These new parties have contributed to an increasing fragmentation in the party system and their longevity is questionable without their charismatic leaders.13 Indeed, Yudhoyono’s PD is widely predicted to see its share of the vote slashed in the April parliamentary elections with its founder no longer on the ballot.

People’s Representative Assembly (DPR) election results (vote percentage)14

|

2009 |

2004 |

1999 |

|

|

PD |

20.85% |

7.45% |

N/A |

|

Golkar |

14.45% |

21.58% |

22.46% |

|

PDI-P |

14.03% |

18.53% |

33.74% |

|

PKS |

7.88% |

7.34% |

1.36% |

|

PAN |

6.01% |

6.44% |

7.12% |

|

PPP |

5.32% |

8.15% |

10.71% |

|

PKB |

4.94% |

10.57% |

12.62% |

|

Gerindra |

4.46% |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Hanura |

3.77% |

N/A |

N/A |

The favourite to win the 2014 presidential election is Jokowi, the current Governor of Jakarta who has yet to be officially nominated as a candidate. An opinion poll conducted in mid-January by Kompas, Indonesia’s largest daily newspaper, found that he would win 43.5 percent of the vote, whilst another poll by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), an influential Jakarta think tank, predicted he would win 34.7 percent. It is widely assumed that Jokowi will be selected by Megawati’s PDI-P, whom he represented in the Jakarta gubernatorial elections, and its failure to officially nominate him has angered some PDI-P members. There has been speculation that the party’s matriarch would like one last run at the presidency for herself, in which case Jokowi could be her running mate. Megawati herself has placed a distant fifth in most presidential surveys, having lost the previous two presidential elections to Yudhoyono. Jokowi has frequently appeared in public with Megawati, whether to either promote his candidacy or reflect some of the governor’s personal popularity onto his party’s leader. Regardless, Megawati has announced that the party will only nominate its presidential candidate after the April parliamentary elections, although this could be a strategic mistake.

If Jokowi is confirmed as its presidential candidate before the April elections, most polls suggest the PDI-P would likely make significant gains in parliament, and overall voter turnout would also increase.15 Jokowi’s candidacy seems likely to draw in many young voters who otherwise would not participate in the elections, and the party needs to secure as many seats in parliament as possible to avoid being forced into a coalition. As Yudhoyono discovered, coalition governments reduce a president’s room for manoeuvre, a situation that could be replicated under a Jokowi-led coalition. However, Megawati could be anxious about losing her family’s control of the party to Jokowi if she backs him for this year’s presidential elections. Before Jokowi’s rise to prominence, Megawati had apparently been grooming her son Prananda Prabowo for leadership of the party, whilst Megawati’s late husband Taufik Kiemas had been backing their daughter Puan Maharani for the role.16 Under a Jokowi presidency Megawati could instead become a powerful kingmaker – akin to India’s Sonia Gandhi – but even without Jokowi the PDI-P is calculating that it could still win the most votes through being the main opposition to Yudhoyono’s unpopular government. Were he not to be selected by the PDI-P it is likely that Jokowi would be approached by other parties to be a vice presidential candidate.

Jokowi first established a reputation for clean and innovative governance when mayor of Solo in Central Java. His achievements there included revitalising public spaces, easing traffic congestion, improving health care delivery, promoting investment and rebranding the city as a Javanese cultural center to rival nearby Yogyakarta. He was re-elected mayor with over 90 percent of the vote. Since becoming governor of Jakarta he has made a name for himself nationally, gaining a reputation for transparency in the midst of a corrupt political system by attempting to replicate his success in Solo. For instance, his deputy uploads recordings of meetings on YouTube and the pair publishes their own salary details online. A reputation for clean governance served Yudhoyono very well at the ballot box until it began to unravel in his second term. Unlike Yudhoyono however, Jokowi appears humble and approachable on his regular walkabouts to meet local residents, an approach he pioneered in Solo. These unscheduled tours often take in the city’s most deprived areas and sometimes involve uninvited appearances at local government offices. Such a hands-on style is a major reason for his high approval ratings both in Jakarta and further afield. In particular, Jokowi’s informal style appeals to young voters who are eligible to vote in national elections for the first time.

As governor Jokowi has attempted to tackle Jakarta’s startling social disparities by instituting several pro-poor policies. Soon after his election in October 2012 he introduced smartcards to provide free access to health care and education for needy residents. The Jakarta Health Card (Kartu Jakarta Sehat, KJS) programme entitles cardholders to free health services at all community health centers and some hospitals across the city. The governor had a target to enroll half of Jakarta’s residents in the scheme by the end of 2013. Likewise, the Jakarta Smart Card (Kartu Jakarta Pintar, KJP) enables students from underprivileged families who hold the card to Rp240,000 (US $21) each month in financial aid to pay for educational materials, stationary, uniforms, transport and even food.17 Jokowi’s administration has also established affordable housing for some Jakarta residents, and boldly increased the minimum wage by 44 percent for 2013.18 These social initiatives have been made possible by an increase in tax revenues generated by the capital’s booming trade and service sector, and by the fact that between 2007 and 2012 Jakarta actually ran a budget surplus of 15-20 percent.19 The governor has also improved revenue raising ability by widening the scope of e-government and online transactions. This has enabled his administration to improve the tax take and reduce opportunities for bribery without increasing taxes, as bureaucrats now have fewer direct dealings with business people. Jokowi has also attempted to tackle Jakarta’s chronic gridlock by reviving long-stalled plans to install a mass transit rail network, funded by loans from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and has been upgrading bus services in the meantime. Polls suggest that most Jakarta residents want him to see out his first term as governor, which ends in 2017.20

Jokowi’s victory in the Jakarta gubernatorial elections against the incumbent Fauzi Bowo, who was backed by Yudhoyono, was perceived as a victory for a new generation of politician over an older, more patrimonial style of politics. Indeed, 52 year-old Jokowi is the only presidential challenger to have arisen from the reformasi democratic era, and unlike many Indonesian politicians does not hail from a privileged background. His policies aimed at Jakarta’s poorest residents also represent a break with the past. As a newcomer to the national political arena Jokowi would face new challenges as president, however. In particular, he would have to deal with the financial backers that fund an expensive presidential campaign and a military that might try to claw back some of its political power. Moreover, there is the question of whether he would be able to push through his own policies or would merely be a proxy for PDI-P leader Megawati, during whose conservative presidency there was little appetite for reform. In opposition, the party vociferously opposed the Yudhoyono government’s plans to decease fuel subsidies, and in March 2014 unveiled a party platform critical of foreign investment.

|

Jakarta governor Jokowi (front right) cycles to work on Fridays (photo by lensaindonesia) |

Trailing second behind Jokowi in most presidential polls has been former Special Forces Commander Prabowo Subianto of Gerindra, campaigning on a platform of pro-poor and pro-agriculture protectionist policies. The Kompas mid-January poll predicted he would win 11.1 percent of the presidential vote if he participated. Unable to secure the backing of Golkar as its presidential candidate, Prabowo and his wealthy tycoon brother Hashim Djojohadikusum founded Gerindra specifically to contest the 2009 presidential elections. In a campaign notable for the party’s lavish spending on television advertising, it garnered 4.5 percent of the vote in the 2009 parliamentary elections and could not build the necessary alliances to field Prabowo as a presidential candidate. Instead, Prabowo ran as running mate to the PDI-P’s Megawati, and the pair won 27 percent of the vote in losing to incumbent Yudhoyono, who secured 61 percent. For the 2014 elections Prabowo’s brother, who also financed Gerindra’s 2009 campaign, has contracted a leading New York advertising agency to improve his sibling’s electability.

Prabowo is the son of Sumitro, an influential economist who held cabinet posts under both Sukarno and Suharto, and was a controversial figure during the late Suharto period. His rapid rise up the military hierarchy was seen as closely linked to his marriage to Suharto’s second daughter Siti Hediati Hariyadi. Having held command posts in both East Timor and West Papua he has been implicated in several cases of human rights abuse, and also played an incendiary role in the riots and demonstrations that accompanied the fall of his then father-in-law in 1998. Prabowo was widely believed to be agitating to become Suharto’s successor, firstly by capturing the post of Armed Forces Commander held by General Wiranto. Troops under Prabowo’s command acted as agent provocateurs in kidnapping and disappearing student activists and stoking the 1998 riots, apparently in order to portray Wiranto as weak for not dealing more forcefully with the protests. However, Suharto’s successor B.J. Habibie faced down Prabowo’s demand to be appointed Armed Forces Commander and Wiranto kept his post. Prabowo subsequently spent a period of exile in Jordan, before returning to Indonesia to join his brother’s resource extraction business and begin his political career.

|

Prabowo Subianto of Gerindra (photo by Dian Triyuli Handoko/Tempo Magazine) |

It has been widely forecast that Gerindra would be unlikely to secure more than 10 percent of the vote in this year’s parliamentary elections, meaning that an alliance with the Yudhoyono’s PD would be necessary for Prabowo to have a run at the presidency. If such an alliance does not materialise Gerindra might instead have to persuade some smaller Muslim parties to support its leader’s candidacy, especially since Prabowo was strongly associated with so-called ‘Green’ Muslim factions in the armed forces in the mid-1990s.21 Yet that strategy appears hamstrung by the continuing electoral weakness of Muslim-based parties in Indonesia and possibly by the fact that Prabowo remains single after divorcing Suharto’s daughter in 1998. Prabowo’s brother and chief campaign financier is also a devout Christian. The PPP is predicted to secure at least five percent of the vote, to make it the largest Muslim-based party in the next parliament, but its chairman Suryadharma Ali seems to have implacable personal differences with Prabowo which would seemingly preclude the PPP backing Gerindra. Two other such parties, the PKB and the National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional, PAN), are both thought capable of winning up to four percent of the vote and Gerindra has recently been in discussions with PAN chairman Hatta Rajasa to be Prabowo’s running mate.22 Gerindra might also secure an alliance with the Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera, PKS), but pollsters believe that it will also struggle to obtain more than five percent. The National Democrat Party (Nasdem) and the Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (Partai Keadilan dan Persatuan Indonesia, PKPI) are two new parties that are expected to win less than two percent, rendering them of marginal significance in forging presidential election alliances.

Prabowo’s former military nemesis Wiranto also established his own electoral vehicle Hanura to contest the 2009 elections. Although Wiranto faces many of the same challenges as Prabowo in securing alliances he is not as divisive a candidate. In the late Suharto years he was part of the so-called ‘red and white’ secular nationalist faction of the military elite which opposed Prabowo’s ‘green’ Islamic faction.23 As Armed Forces Commander from February 1998 to October 1999, Wiranto was a central player in the early reformasi period, in which he resisted hardliners such as Prabowo by refusing to impose military rule. Instead he played something of a restraining role during the post-Suharto transition, and subsequently supported the reduction of the military’s reserved seats in parliament and the separation of the police from the armed forces. However, Wiranto (along with five other generals) was also indicted by the UN-backed Special Crimes Unit in East Timor for crimes against humanity for failing to stop the razing of East Timor by the Indonesian military and its militias, after that territory’s vote for independence in 1999. He entered politics as Golkar’s candidate in the 2004 presidential elections, placing third in the contest behind Yudhoyono and Megawati with 22.19 percent of the votes. In the 2009 elections he campaigned unsuccessfully for the vice presidency as running mate to Golkar chairman Jusuf Kalla. Wiranto has placed fourth in most polls for this year’s presidential elections, and like Prabowo will need to form strategic alliances with other parties to participate in this year’s presidential contest.

|

Wiranto’s campaign blog emphasises his military service |

The current Golkar chairman and presidential candidate is prominent businessman Aburizal Bakrie, another controversial figure since he and his brothers control the huge Bakrie Group founded by their father. Among the conglomerate’s many subsidiaries is oil and gas company Lapindo whose drilling triggered a huge mudflow in 2006 that displaced thousands of residents in Sidoarjo, East Java, destroying surrounding homes and farmland. Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) held the company responsible for the man-made disaster that it deemed a human rights violation. In 2013 Bumi Resources, another Bakrie asset and the largest thermal coal exporter in Asia, was involved in an unsavoury public row with the Rothschild banking dynasty over control of the firm. The Golkar chairman has been upbeat that neither of these scandals will damage his electability but there has been some disquiet within the party over his candidacy.24

|

Aburizal Bakrie on the campaign trail (photo by Muhamad Solihin/VIVAnews) |

Golkar is widely forecast to gain 12 to 15 percent of the vote in the parliamentary elections but the party has yet to secure a presidential election victory in the post-Suharto era, and Bakrie is currently the third favourite to win this year’s contest. The Golkar chairman has been a political insider since the Suharto era, having served as President of the ASEAN business forum (1991-1995), President of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (1994-2004), Coordinating Minister for Economy (2004-2005) and Coordinating Minister for People’s Welfare (2005-2009). Although Golkar retains its New Order logistical advantages over other parties in more remote parts of the archipelago, it could suffer from breakaway parties Gerindra and Hanura drawing away some of its votes, and the advancing age of many of its leaders who started their political careers under Suharto.

Meanwhile, Yudhoyono’s PD has yet to select a presidential candidate. Without its patron on the ballot, support for the party is predicted to drop below 10 percent of the vote in 2014, underscoring how important a leader’s personal charisma is for a party’s election prospects. As a consequence, there have been discussions within the PD that if its share of the vote is smaller than Golkar’s, then Yudhoyono will back Golkar if his brother-in-law, Pramono Edhie Wibowo, is selected as Golkar’s vice presidential candidate. Under the present system a presidential candidate typically nominates a running mate after the legislative elections in order to broker alliances to meet the electoral threshold to run for president. Moreover, this enables smaller parties to field candidates in the presidential elections. Most notably this was the case in 2004 when Yudhoyono selected Golkar chairman Jusuf Kalla as his running mate after Golkar had secured the most seats in parliament. This strategy gave Yudhoyono a much stronger power base in parliament since his own party had secured only 55 seats (from 7.45 percent of the vote), compared to Golkar’s 128 seats (from 21.58 percent of the vote). However, this prompted speculation as to whether it was Yudhoyono or Kalla who was actually the most powerful man in government. Yudhoyono’s personal popularity was boosted by his announcement of several timely fuel price reductions following the collapse of international oil prices after August 2008. A net oil importer since late 2004, this policy resulted in a stunning parliamentary election success for Yudhoyono’s PD, allowing its patron the luxury of disregarding party considerations when choosing a running mate. For the 2009 presidential campaign Yudhoyono selected a non-party figure instead, former central bank governor Boediono, although this subsequently weakened his standing vis-a-vis parliament.

Political Islam

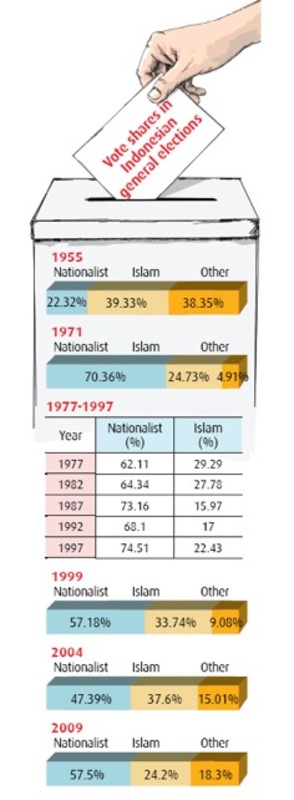

Indonesia is the largest Muslim country in the world, with around 88 percent of its 240 million population identifying as Muslims. Unlike in neighbouring Malaysia, however, political Islam has not become a dominant electoral force. Whilst Islamic-based parties secured a combined 39.33 percent of the vote in the 1955 elections, Suharto’s authoritarian rule subsequently restricted the political mobilisation of Islamist forces (see table below). Generally lacking the charismatic leaders of secular parties, Islamic-based parties have been unable to take advantage of the greater political opportunities since 1998, and continue to split the Islamic vote amongst them. In a bid to increase their electability, all of Indonesia’s Islamic parties jettisoned their campaigns for Sharia law and adopted more pluralistic party platforms. This stands in marked contrast to their counterparts contesting the 1955 election, all of which advocated an Islamic State of Indonesia (Negara Islam Indonesia) with Islam at the centre of a revised constitution.

This shift seems to reflect the triumph of the inclusive principles on which Indonesia was founded, principles to which Indonesia’s secular nationalist parties successfully appeal. Whilst Islam is the sole state religion in Malaysia, it is only one of six recognised monotheistic religions in the more inclusive Indonesian constitution.25 Moreover, Islamisation in Malaysia has largely been designed and implemented by political elites in Kuala Lumpur, partly as a strategy to marginalise ethno-religious minorities, whereas in Indonesia it has been driven by civil society groups with only sporadic support from the state.26 Islamic parties have been represented in all of Indonesia’s coalition governments since 1999 but their electoral prospects have been hit by recent corruption scandals. In 2013 the former leader of the PKS was jailed for 16 years for corruption, and now the Corruption Eradication Commission is investigating two separate cases that threaten to implicate the leaderships of the PPP and the smaller Crescent Star Party (Partai Bulan Bintang, PBB). Although there is awareness that corruption affects all political parties it is particularly damaging for Islamic parties since they position themselves on the moral high ground above their secular rivals. Therefore, these graft allegations will likely impact the electoral chances of all Islamic-based parties.27 Surveys predict that the combined vote of the five parties which appeal to Islamic voters – PPP, PKS, PBB, PAN and PKB – would total only around 21 percent, less than they collectively won in the 2009 election, with each struggling to gain more than five percent.28

|

Vote shares in the previous 10 Indonesian elections (source The Jakarta Post) |

The decline in the electoral appeal of the Islamic parties since 2004 has been accompanied by an increase in religious intolerance and the rise of the fundamentalist vigilante group Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam, FPI). Formed in the reformasi era of 1998 when restrictions on political assembly and free speech were lifted, the FPI positions itself as a moral police force trying to enforce strict compliance with Sharia law in Indonesia. It has become notorious for its sweeps of nightclubs, bars, brothels, gambling dens and even street vendors, particularly during the month of Ramadan, actions which have been popular with some conservative Muslims.

The FPI is strongest in Jakarta and West Java, where it has forced the closure of many churches and fatally attacked members of the Ahmadiyah community, a minority Islamic sect. However, during the last five years it has spread across Indonesia and clashed with ethnic and religious minorities in Sumatra, Sulawesi and Kalimantan, typically when the FPI tries to prevent minority religions from establishing (temporary or permanent) places of worship. The FPI has also become well known in the mainstream media for the protests that forced the cancellation of Lady Gaga’s Jakarta concert in 2012, and the jailing of the editor of Indonesia’s Playboy Magazine on charges of public indecency in 2010.

The FPI finances itself by extorting bars and nightclubs across Jakarta and West Java, and it is also rumoured to receive financial support from political parties, the police and military. In 2011 leaked American diplomatic cables surfaced on WikiLeaks which alleged that the Indonesian security forces have been sponsoring the FPI to pressure the political establishment. The Indonesian military similarly used Islamic hardliners to help massacre hundreds of thousands of alleged Communists in 1965-66, and since then Islamic militia have been deployed by the security forces in conflicts in East Timor, Aceh, Papua, Sulawesi and Maluku. There is also speculation that the FPI might play a similar role for mainstream Islamic organisations, including NU and Muhammadiyah, who have conspicuously failed to denounce the FPI’s violent actions.29

Despite using mass demonstrations, threats and violence to intimidate its targets, the FPI has so far avoided being labelled a terrorist group because the Yudhoyono government has been afraid of losing the support of Muslim voters. Indeed, the judiciary and the police have also been very reluctant to crack down on the organisation, and some Islamic parties have even publicly supported the FPI. Most cases against FPI members never make it to court, and when convictions are made lenient sentences are the norm. Whilst the DPR has debated banning the organisation, both politicians and judges do not want to be seen as un-Islamic by attacking the FPI. Both NU and Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s two largest civil society organisations, have also previously rejected calls to ban the group. The FPI even targets expressions of traditional Indonesian culture, and its rise indicates a mainstream political shift to the right, in which conservative Islam appears to have become too significant a constituency for political parties to antagonise.

|

An Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) rally in Jakarta (photo by Supri/Reuters) |

This failure to prosecute the FPI has prompted the United Nations, the European Union and members of the U.S. Congress to criticise Indonesia over its lack of protection for the religious minorities which constitute more than 12 percent of its population. The FPI insists it is exercising its democratic right to freedom of expression but its actions undermine both the country’s ongoing democratic transition and the inclusive principles on which Indonesia was founded. Much stronger law enforcement is necessary to tackle religious harassment and protect the country’s pluralist foundations. The state’s reluctance to reign in the FPI represents a major failing of Yudhoyono’s two terms in office and sets a dangerous precedent for future governments.

Media Influence

Another notable aspect of Indonesia’s democratic transition has been the changing role of the media. Soon after Suharto resigned in May 1998 the government relaxed previously strict censorship rules leading to a rapid expansion in print media, television channels and radio stations. One of President Wahid’s first acts on taking office in 1999 was to abolish the Ministry of Information, further consolidating media freedom. In the following decade the number of newspapers and magazines tripled, the amount of national television networks doubled and around 200 local television networks appeared across the country. Between 1998 and 2008 the number of households with at least one television increased almost threefold.30 Internet usage also increased dramatically and by June 2013 Indonesia had almost 64 million active Facebook users, the fourth largest number behind the United States, Brazil and India.31 The country also has around 30 million Twitter users and in 2012 Jakarta became ‘the world’s most active Twitter city’, ahead of Tokyo, London and New York.32 Jokowi’s skillful use of social media enhances his appeal among young voters, 67 million of whom are eligible to participate for the first-time in this year’s national elections.33 Research indicates that 90 percent of Indonesians between the ages of 15 and 19 regularly go online, 80 percent of the country’s internet users are under 35 years-old and around 90 percent of all internet traffic goes to social networking sites.34

According to Freedom House, “Indonesia’s media environment continues to rank among the most vibrant and open in the region”.35 Indeed, the media frequently takes the state to task on issues such as corruption, environmental degradation and violence against religious minorities, and there is a growing awareness among politicians and bureaucrats that media reports of wrongdoing can break a career. Moreover, it has been argued that the explosion of social media in Indonesia has fostered a climate in which popular online trends can positively influence the political agenda and deliver actual policy results.36 On the other hand, this developing watchdog ability is countered by spurious defamation lawsuits filed by powerful individuals, who have been able to bribe corrupt judges and law enforcement officials to stifle media scrutiny of their affairs.

Often referred to as the fourth pillar of democracy, after the judiciary, legislative and the executive, the media plays a key role in holding the other pillars accountable. This is especially the case in a country such as Indonesia in which the integrity of the first three pillars is questionable. However, the increasing influence of the mass media in Indonesia, in particular television, has been linked to the growing tendency of wealthy entrepreneurs to seek high office. Of the 12 political parties on the ballot papers in this year’s elections three have media moguls in leadership roles. Golkar chairman Aburizal Bakrie owns two television stations, TVOne and ANTV. Likewise, Hanura’s vice presidential candidate Hary Tanoesoedibjo is the owner of Media Nusantara Citra Group which runs three national terrestrial stations – RCTI, Global TV and MNC TV – among the 20 that it controls. Surya Paloh, chairman of the new NasDem Party, runs news channel MetroTV whilst Dahlan Iskan, owner of the Jawa Pos Group, is widely tipped to be the PD’s candidate to succeed Yudhoyono. As a consequence, there are concerns that the development of the Indonesian media’s watchdog role will be stunted.

This is significant since a recent survey has found that most Indonesians rely heavily on television coverage of political parties when deciding who to vote for.37 Indeed, television remains the country’s primary news source. Research conducted in 2012 with Indonesians over the age of 10 revealed that 91.7 percent watch television, compared to 18.57 percent who listen to radio and 17.66 percent who read newspapers and magazines.38 Biased television coverage of the political scene has already been noted in the run up to this year’s elections.39 In December 2013 the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) admonished six television channels owned by Aburizal Bakrie, Hary Tanoesoedibjo and Surya Paloh for excessive and partial coverage of their owners’ election bids. The Bakrie family’s TV One and ANTV were deemed to have run 430 Aburizal Bakrie and Golkar promotional videos in October 2013 alone. Likewise, Hary Tanoesoedibjo’s MNC TV, RCTI and Global TV stations were all criticised for broadcasting programmes championing the candidacy of its owner and his Hanura party chairman Wiranto. Meanwhile, Metro TV received censure for excessive coverage of the NasDem Party and its party chairman Surya Paloh, who happens to own the station.40

Even in a mature democracy such as Italy, experience shows that having a media mogul as head of government tends to compromise coverage of the leader and his administration. With Silvio Berlusconi as prime minister, the Freedom of the Press Global Survey of 2004 downgraded the status of the Italian media from ‘free’ to ‘partly free’ in light of his influence.41 Berlusconi was able to silence critics and reduce coverage of his many scandals due to his control of a large section of the Italian media, including state television. Likewise, in Thailand the prime ministership of Thaksin Shinawatra was dogged by allegations of a conflict of interest as Thaksin used his media empire to manipulate reporting of his activities.42 In Indonesia the increasing influence of the mass media, especially television, has already been linked to the greater personalisation of politics. Although Indonesia’s lively media has developed into one of the most free in Asia, the Freedom of the Press Global Survey of 2013 ranks it as only ‘partly free’ due to restrictive laws, such as one prohibiting blasphemy, and harassment of journalists.43 The preponderance of vaguely worded laws on the books in Indonesia would make fertile ground for a media tycoon looking to roll back press freedom if elected to executive office. This is of particular concern since the political and economic dominance of Indonesia oligarchs is already well served by a corrupt legal system and the relative organisational weakness of civil society.44

The Spectre of the Military

Whilst the military has lost much of its power since the Suharto era, the presence of New Order generals Prabowo and Wiranto on the ballot papers inevitably raises the question of what influence it will have over future governments. Unlike in Thailand and the Philippines, the political influence of the military has further declined since 2004. Much of the credit for this turnaround must go to Yudhoyono himself. In 2004 the armed forces lost its 38 reserved seats in the national parliament and also its 10 percent share of all seats in local law making bodies. Likewise, the military’s influence in the regions was further eroded by the democratisation and decentralisation reforms instituted after 1999, as the power of successful businessmen, local officials and civilian activists rose. As a result, in 2010 only the provincial governors of Central Java, Central Sulawesi and West Papua were former military men, whilst the other 29 governors had civilian backgrounds. This contrasts with the Suharto era, in which military officers (usually retired) comprised some 80 percent of provincial governors in the early 1970s and around 40 percent in the late 80s.45

The military also lost key cabinet and institutional posts under Yudhoyono. The Ministry of Home Affairs with its control of police powers had been a bastion of its political power since the 1960s, but in 2009 a career civil servant was appointed to head up the crucial ministry, whose tentacles reach right across the archipelago. Whilst Yudhoyono’s 2009 cabinet did include four retired military officers, the Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs was the only major portfolio on offer. The military influence in the Constitutional Court (founded in 2003) has also been reduced, and it has lost control over the State Intelligence Agency (Badan Inteligen Negara, BIN), which briefs the president on major political issues. For the first time, a former police chief was selected to head the agency in 2009, thus reducing work opportunities in BIN for military officers.46

Nevertheless, Yudhoyono’s record of military reform has been mixed, allowing the military to retain some of its long held privileges and influence. Most noteworthy is that the president has reduced the pace of institutional reform, in particular defending the military’s territorial command structure, which ensures its presence in almost every corner of the archipelago down to the village level. This command structure was heavily implicated in human rights abuses during the Suharto period and its aftermath, investigations which Yudhoyono has also blocked. His party has also fielded many more retired officers as candidates in national and regional elections than either Golkar or the PDI-P. For instance, in the 2009 parliamentary elections, 6 percent of PD MPs came from a military background, compared to a national average of 2 percent.47 Whilst Indonesia has had a succession of civilian defence ministers in the post-Suharto era, Yudhoyono has also continued to appoint active military officers to most senior staff positions in the ministry.48 Moreover, the appointment of Djoko Suyanto, a class mate of Yudhoyono’s at the Indonesian military academy, to the post of Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs continued a long running tradition that this cabinet position be held by a former armed forces commander, Djoko having been appointed commander in 2006. This ministry is also staffed by active military officers with the power to direct other government departments and with direct access to the president.49

In much the same way as Suharto before him, Yudhoyono has taken a very personal approach to controlling the military, and it is doubtful whether a leader from a civilian background could have had the same success. Central to this strategy has been the appointment of his peers from the military academy’s class of 1973, such as Djoko and Sutanto as the head of BIN, to senior positions. Like Suharto, he has also promoted his former subordinates and family members through the ranks to ensure control over the military.50 Whilst such nepotism has drawn criticism, it has significantly reduced the military’s appetite for independent action. However, with Yudhoyono’s term in office set to expire, there is concern that hardline officers will attempt to claw back some of the military’s political clout. For instance, in a speech last October Lieutenant General Gatot Nurmantyo, head of Kostrad the army’s strategic command, was critical of Indonesia’s democracy and questioned the wisdom of free elections.51 Such public statements demonstrate the growing assertiveness of conservative generals in challenging the military’s removal from politics, following their success in stifling military reform at the beginning of Yudhoyono’s second term.52

Nurmantyo’s comments are significant because of his rapid rise up the military hierarchy; having previously been governor of the military academy, East Java regional commander and leader of the army’s training command.53 Whilst passed over by Yudhoyono for the post of army commander, it is possible that Nurmantyo could rise further under a more sympathetic president. Moreover, growing voter apathy might enable hardliners like Nurmantyo to reverse some of the gains Indonesia has made in reforming military-civil relations. A popular leader such as Jokowi with a clear mandate to continue reform may well be necessary to prevent some of these gains being eroded. However, he represents Megawati’s PDI-P, which has long been cautious on military reform, mindful of the fact that the military was partially responsible for her elevation from vice president to president in 2001. More recently, Prabowo ran as Megawati’s running mate in the 2009 presidential elections. Intriguingly, there are also signs that some Indonesians are growing nostalgic for the stability of the authoritarian Suharto period, with stickers and T-shirts of the Smiling General becoming increasingly visible in Jakarta.54 In addition to Golkar, Suharto protégés Wiranto and Prabowo are hoping to translate this nostalgia into votes at the ballot box.

|

Suharto T-shirts on sale (photo by Zakir Hussain) |

Conclusion

When the Suharto era finally ended, the prognosis for Indonesia becoming a stable democracy was not good. A rapid return to military rule, continued stagnation or a violent Balkanisation into several smaller states were among the gloomy predictions. Yet in the following decade it has become arguably the freest country in Southeast Asia, despite some serious structural issues and a continued, if weakened, legacy of military rule. Post-Suharto improvements in both political freedom and civil liberties mean that Indonesia is now also one of the freest Muslim-majority states. As the country’s first directly elected president, Yudhoyono enjoyed an almost unprecedented degree of legitimacy. During his two terms in office democracy has been consolidated, politics stabilised and the military influence’s reduced. As a former general, Yudhoyono was able to use his personal networks within the security forces to curtail the influence of certain anti-democratic actors. However, most of these gains were made during his first term in office (2004-09), and since 2009 hardliners within the armed forces have been able to block further military reform. Despite sustained economic growth fed by resource exports, Indonesian voters who wholeheartedly embraced Yudhoyono’s vision of an efficient and clean state at the ballot box in 2004 and 2009 have been disappointed by the corruption scandals and slowing pace of reform during his second term.

Although his popularity was boosted by timely oil price reductions before his second election win, Yudhoyono’s victories demonstrated that reform resonates with Indonesian voters. Among the major challenges facing the country’s next president are reducing poverty and income inequality, tackling endemic corruption, reforming the state’s labyrinthine bureaucracy, upgrading the country’s creaking infrastructure and safeguarding the rights of religious minorities. Current Jakarta governor Jokowi has shown a commitment to clean government and a concern for the poverty-stricken unrivalled by both his predecessors and other presidential hopefuls, and he is the only potential presidential candidate to have arisen from the post-Suharto democratic era. Likewise, pro-poor policies contributed heavily to Yudhoyono’s 2009 success. A Jokowi victory would signal a generational change away from politicians who were either military protégés of Suharto or oligarchs who owed their fortunes to him, all of whom can count on backing from the military, the bureaucracy and/or big business. Given that parliament has previously opposed efforts by the Corruption Eradication Commission, the next president will need to forcefully back the agency in order to impove the country’s investment climate amid slowing economic growth. Whilst successful as mayor of Solo and governor of Jakarta, Jokowi will find the challenge much bigger at the national level where he will need to balance the demands of coalition partners and the financial backers of any election campaign. Indeed, corruption tends to increase in the run up to elections as parties and candidates seek political funding.55 However, it is also possible that his wide popular base might revolutionise campaign funding in Indonesia with his many supporters making small donations that total a significant amount. Even though it is widely assumed that he will become the PDI-P’s presidential candidate, how much freedom he would have to dictate party policy is unknown. Likewise, Megawati could be concerned that her family will lose control of the party to him in future. The PDI-P has long stood for an inclusive secular nationalism that recalls Indonesia’s founding under Sukarno. During the PDI-P’s only previous presidency, under Sukarno’s daughter Megawati, there was little appetite for political or military reform.

Jokowi aside, surveying the list of confirmed candidates for the 2014 presidential elections does not inspire great confidence for improved governance and further democratic consolidation. As a reaction to Yudhoyono’s perceived indecisiveness, a candidate who appears strong and resolute could garner a greater share of the votes this year. Prabowo and Wiranto, Suharto-era generals both linked to human rights abuses, are among the confirmed presidential candidates, and their respective election vehicles have so far received the most campaign donations.56 Both are well placed to tap into growing nostalgia for Suharto’s strong rule. Such sentiment indicates that despite the progress Indonesia has made its democratic gains are not irreversible and major challenges remain in improving the quality of governance, particularly in applying the rule of law to the political and economic elite. Even Yudhoyono, who enjoyed high personal approval ratings and led a political party with the most seats in parliament, found improving governance increasingly difficult in his second term. Moreover, a fundamental question is whether a leader from a civilian background, without Yudhoyono’s military networks to draw on, can continue to hold the armed forces in check, especially at a time when military hardliners seem to be growing in confidence. In addition, recent trends indicate a creeping economic nationalism.57 New trade and industry laws passed in February 2014 seek to insulate domestic firms from international competition and follow similar (partially retracted) measures enacted in 2013 that restricted imports of horticultural products.58 Prabowo, second favourite to win the presidential election, has called for further protectionist measures, such as banning rice imports and gas exports, and is considered wary of foreign investment and market forces. The PDI-P too has unveiled a party platform that is critical of foreign investment.

Party politics in Indonesia, as in Thailand and the Philippines, has become increasingly personalistic and presidential in which the charisma of the leader eclipses a party’s policies. In both Thailand and the Philippines this coincided with a resurgence of military influence, which has yet to occur in Indonesia. Instead, voter apathy has gradually taken hold after the euphoria and high turnout of the 1999 elections. Those who either did not vote or spoiled their ballot papers accounted for some 23.3 percent of the electorate in 2004 and 39.1 percent in 2009. This percentage is widely forecast to rise again in 2014, especially if Jokowi is not among the candidates.59 Nevertheless, democracy in Indonesia will most probably continue, but the possibility of it being undermined and subverted as in Thailand and the Philippines, cannot be discounted if the presidency is captured by a Suharto-era oligarch or former general. Further democratic consolidation will likely require a resounding victory by a reform-minded presidential candidate capable of implementing such a programme.

David Adam Stott is an associate professor at the University of Kitakyushu, Japan and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. His work centers on the political economy of conflict in Southeast Asia, Japan’s relations with the region, and natural resource issues in the Asia-Pacific.

Recommended citation: David Adam Stott, “Indonesia’s Elections of 2014: Democratic Consolidation or Reversal?,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol.12, Issue 10, No. 2, March 10, 2014.

Notes

1 According to Freedom House country rankings for 2011, 2012 and 2013. Indonesia was the only state in Southeast Asia to be ranked ‘free’ in terms of both political rights and civil liberties. East Timor, the region’s next highest ranked country, was adjudged only ‘partly free’ for each of those three years.

2 His government spent approximately US$2 billion between June 2008 and April 2009 on compensation payments for increased fuel prices, micro-credit programs and schooling allowances. See Marcus Mietzner (2009), ‘Indonesia’s 2009 Elections: Populism, Dynasties and the Consolidation of the Party System’, Lowy Institute for International Affairs.

3 International Monetary Fund (2012), Indonesia: Staff Report for the 2012 Article IV Consultation

4 See the Corruption Perceptions Index of 2013. Corruption prosecutions actually increased in 2013, however.

5 Ehito Kimura (2012), Political Change and Territoriality in Indonesia: Provincial Proliferation, Routledge, London

6 Dirk Tomsa (2008), Party Politics and Democratization in Indonesia: Golkar in the Post-Suharto Era, London, Routledge, p.190

7 Since its founding in 2003, the Corruption Eradication Committee (KPK) has prosecuted 72 members of parliament, eight government ministers, six central bankers, four judges and dozens of CEOs, achieving a 100 percent conviction rate.

8 Marcus Mietzner & Edward Aspinall (2010). ‘Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia: An Overview’, in Edward Aspinall & Marcus Mietzner (ed.), Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia: Elections, Institutions and Society, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), Singapore, p.4

9 ibid, p.8

10 ibid, p.10

11 ibid, p.12

12 Newcomers Gerindra and Hanura were not represented either although Yudhoyono was later keen to bring them in when conducting a reshuffle.

13 Dirk Tomsa (2010), ‘The Indonesian Party System after the 2009 Elections: Towards Stability?’ in Edward Aspinall & Marcus Mietzner (ed.), Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia, pp. 141-159.

14 Data from the Indonesian Election Commission (KPU)

16 Hans David Tampubolon, ‘Sukarno’s Blood Still Vital For PDI-P’, The Jakarta Post, April 1, 2010

17 Although not school fees, which are covered by a separate programme.

20 The Jakarta Post, ‘Jakartans Want Jokowi To Stay: Survey’, February 10, 2014

21 Andreas Ufen (2009), ‘Mobilising Political Islam: Indonesia and Malaysia Compared’, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 308-333

23 Ufen 2009.

24 Ridwan Max Sijabat, ‘Opposition Grows Within Golkar To Aburizal’s Presidential Bid’,

The Jakarta Post, April 23, 2012 and John McBeth, ‘Golkar Wavering Over Its Candidate’, The Straits Times, January 29, 2013

25 The others are Catholicism, Protestantism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Confucianism.

26 Ufen 2009.

28 The PPP, PKS and PBB are explicitly Islamic in their charter whilst the PAN and PKB are regarded as appealing to Muslim voters.

30 Ariel Heryanto (2010), ‘Entertainment, Domestication, and Dispersal: Street Politics as Popular Culture’, in Edward Aspinall & Marcus Mietzner (ed.), Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia, p. 192.

31 Mariel Grazella, ‘Facebook Users Rise To 64m In Indonesia’, The Jakarta Post, June 18, 2013. These figures do not take into account the number of Facebook users in China, where it is officially blocked.

32 Research conducted by Semiocast, a social media analytics company, cited in George Steptoe, ‘Sharing Is Caring’, Southeast Asia Globe, November 12, 2013.

33 Jokowi had 1.3 million Twitter followers at the time of writing.

34 Research by Yahoo! and TNS cited in Steptoe (2013).

35 Freedom House, Freedom of the Press Global Survey of 2013: Indonesia

36 This is the view of Enda Nasution, the ‘father of Indonesian bloggers’. For example, #SaveKPK hashtag, critical of Yudhoyono’s inaction over police harassment of the KPK, reached 9.4 million internet users and forced the president to intervene. Cited in Steptoe (2013).

37 The survey was conducted in December 2013, involving 1,200 respondents from all of Indonesia’s 33 provinces, with a margin of error of 2.83 percent. See The Jakarta Post, ‘Voters Rely On TV News, Not Campaign Ads: Indonesia Survey’, January 15, 2014

38 Haeril Halim, ‘Media Told To Remain Impartial During Polls’, The Jakarta Post, January 4, 2014

40 ibid

42 Kelvin Rowley, ‘The Downfall Of Thaksin Shinawatra’s CEO-State’, APSNet Policy Forum, November 9, 2006. Thaksin sold his family’s media and telecoms empire to Singapore’s Temasek in 2006.

43 See Freedom House, Freedom of the Press Global Survey of 2013: Indonesia

44 Jeffrey A. Winters (2013), ‘Wealth, Power, and Contemporary Indonesian Politics’, Indonesia Vol. 96, pp. 11-33

45 Marcus Mietzner (2011), ‘The Political Marginalization of the Military in Indonesia: Democratic Consolidation, Leadership, and Institutional Reform’, in Marcus Mietzner (ed.), The Political Resurgence of the Military in Southeast Asia: Conflict and Leadership, Routledge, London and New York, p.128

46 ibid, p. 132-135

47 ibid, p. 142

48 ibid, p. 144

49 ibid

50 ibid, p. 145

51 Kompas, ‘TNI Expresses “Doubts” About Democracy, Desire To Return To Politics’, October 28, 2013

53 John McBeth, ‘A President’s Unfulfilled Promise’, The Straits Times, December 19, 2013

54 These depict a smiling Suharto asking in Javanese: “How’re things? They were better in my time, no?” See Zakir Hussain, ‘Growing Nostalgia In Indonesia For Life Under Suharto’, The Straits Times, January 29, 2014

57 Such was the pattern during the New Order when economic liberalisation polices were wound back as resource-driven growth slowed.

58 Vikram Nehru (2013), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 139-166

59 The Jakarta Post, ‘Bawaslu Anticipates “Golput”‘, November 24, 2013