Introduction

In Part I of this series we looked at the battlefield experiences of Sōtō Zen Master Sawaki Kōdō during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. Sawaki’s battlefield reminiscences are relatively short, especially as he had been severely wounded early in the war. Nevertheless, he was able to express the relationship he saw between Zen and war on numerous occasions in the years that followed.

In the case of Zen Master Nakajima Genjō (1915-2000) we have a Rinzai Zen Master whose battlefield experiences are much more extensive, extending over many years. On the other hand, Nakajima’s postwar discussions of his battlefield experiences are far more limited than those of Sawaki. This is not surprising when we consider that, unlike the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, which Japan won, the Asia-Pacific War of 1937-45 of which Nakajima was a part ended in disaster for Japan. Nevertheless, in terms of understanding the relationship between Zen and war, Nakajima’s battlefield experiences have much to teach us.

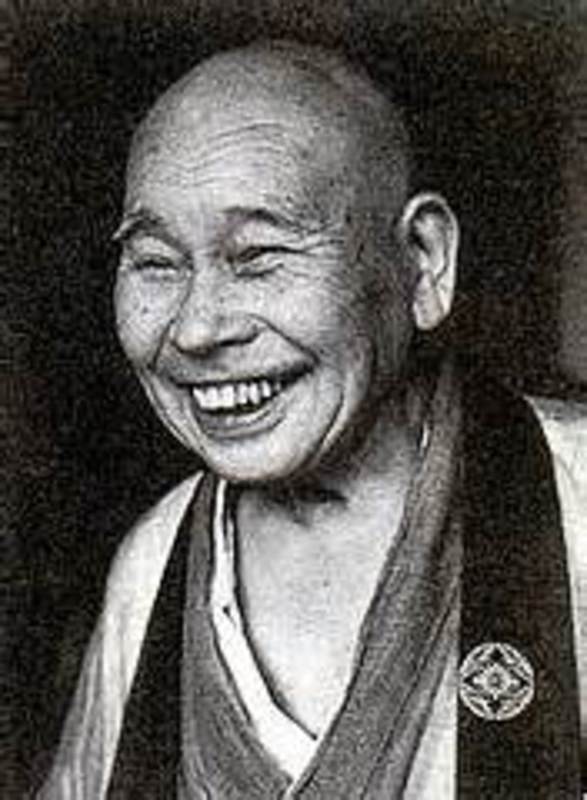

In Nakajima’s case there is no controversy over his battlefield experiences and related views since he recorded them in a very compact and clearly written form. The process by which I acquired this material began with a visit to the village of Hara in Japan’s Shizuoka Prefecture in late January 1999. It was there I met Nakajima for the first time when he was eighty-four years old and the abbot of Shōinji temple and head of the Hakuin branch of the Rinzai Zen sect.1 Shōinji is famous as the home temple of Zen Master Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768), the great early modern medieval reformer of Rinzai Zen. Although I didn’t know it at the time, Nakajima had little more than another year to live.

|

Shōinji temple. |

Nakajima told me that he first arrived at Shōinji at the age of twelve and formally entered the priesthood at age fifteen. He eventually became a disciple and Dharma successor of Yamamoto Gempō (1866-1961) who was abbot of both Shōinji and nearby Ryūtakuji temples, and one of the most highly respected and influential Rinzai masters of the modern era. Yamamoto was so respected that in the immediate postwar period he was selected to head what was then a single, unified Rinzai Zen sect.2 In the West, Yamamoto is perhaps best known as the master of Nakagawa Sōen (1907–1984) who taught and influenced many early Western students of Zen in the postwar era.

In the course of our conversation Nakajima informed me that he had served in the Imperial Japanese Navy for some ten years, voluntarily enlisting at the age of twenty-one. Significantly, the year prior to his enlistment Nakajima had his initial enlightenment experience (kenshō). Thus, even though he was not yet recognized as a “Zen master,” he was nevertheless an accomplished Zen practitioner on the battlefield.

Having previously written about the role of Zen and Zen masters in wartime Japan, I was quite moved to meet a living Zen master who had served in the military. That Nakajima was in the Rinzai Zen tradition made the encounter even more meaningful, for up to that point none of the many branches of this sect had expressed the least regret for their fervent and unconditional support of Japanese militarism.3 Given this, I could not help but wonder what Nakajima would have to say about his own role, as both enlightened priest and seasoned warrior, in a conflict that claimed the lives of so many millions.

To my surprise, Nakajima readily agreed to share his wartime experiences, but, shortly after he began to speak, tears welled up in his eyes and his voice cracked. Overcome by emotion, he was unable to continue. By this time his tears had triggered my own, and we both sat round the temple’s open hearth crying for some time. When at length Nakajima regained his composure, he informed me that he had just completed writing his autobiography, including a description of his years in the military.

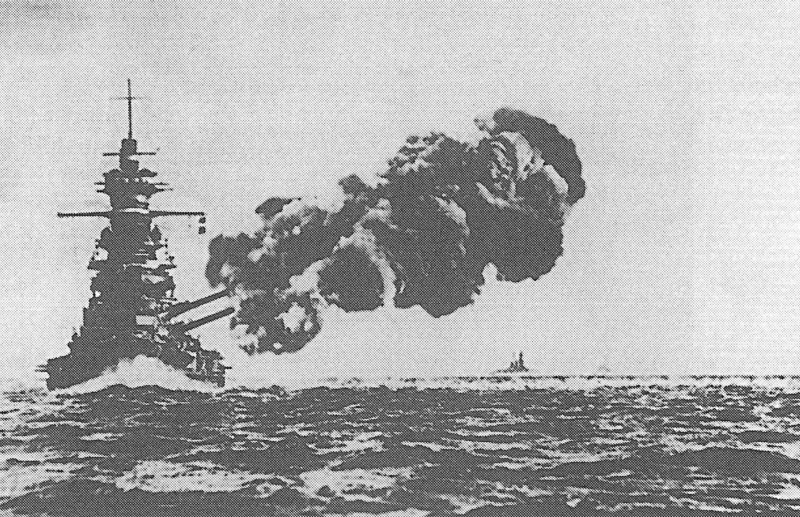

Nakajima promised to send me a copy of his book as soon as it was published. True to his word, at the beginning of April 1999 I received a slim volume in the mail entitled Yasoji o koete (Beyond Eighty Years). The book contained a number of photos including one of him as a handsome young sailor in the navy and another of the battleship Ise on which he initially served. Although somewhat abridged, this is his story.4 It should be born in mind, however, that his reminiscences were written for a Japanese audience.

|

The Japanese Imperial Navy battleship “Ise”. |

In the Imperial Navy

Enlistment I enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1936. On the morning I was to leave, Master Yamamoto accompanied me as far as the entrance to the temple grounds. He pointed to a nearby small shed housing a water wheel. “Look at that water wheel,” he said, “as long as there is water, the wheel keeps turning. The wheel of the Dharma is the same. As long as the self-sacrificing mind of a bodhisattva is present, the Dharma is realized. You must exert yourself to the utmost to ensure that the water of the bodhisattva-mind never runs out.”

|

Yamamoto Gempō. |

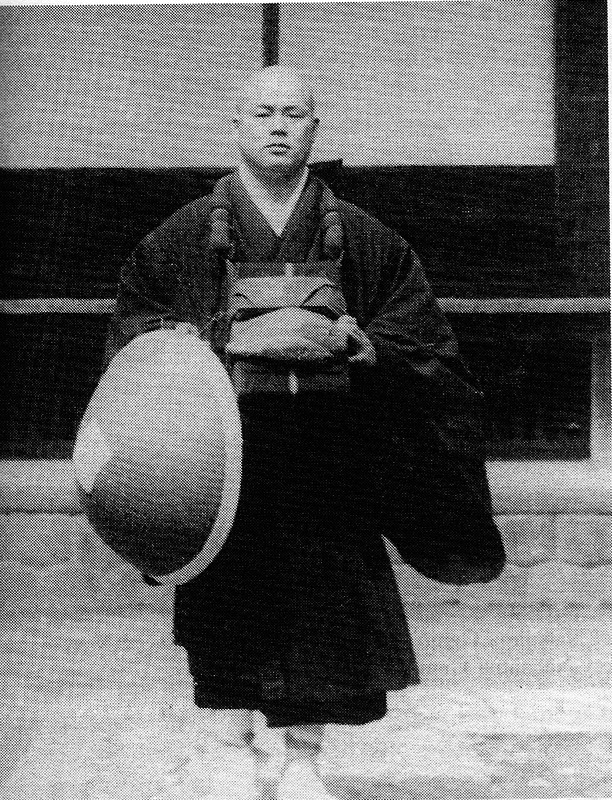

Master Yamamoto required that I leave the temple dressed in the garb of an itinerant monk, complete with conical wicker hat, robes, and straw sandals. This was a most unreasonable requirement, for I should have been wearing the simple uniform of a member of the youth corps.

I placed a number of Buddhist sutras including the “Platform Sutra of the Sixth Zen Patriarch” in my luggage. In this respect the master and I were of one mind. While I had no time to read anything during basic training, once assigned to the battleship Ise I did have days off. The landlady where I roomed in Hiroshima was very kind, and my greatest pleasure was reading the recorded sayings of the Zen patriarchs.

In the summer of 1937 I was granted a short leave and returned to visit Master Yamamoto at Shōinji. It was clear that the master was not the least bit worried that I might die in battle. “Even if a bullet comes your way,” he said, “it will swerve around you.” I replied, “But bullets don’t swerve!” “Don’t tell me that,” he remonstrated, “you came back this time, didn’t you?” “Yes, that’s true . . .” I said, and we both had a good laugh.

|

Nakajima Genjō in priest robes. |

While I was at Shōinji that summer I successfully answered the Master’s final queries concerning the kōan known as “Zhao-zhou’s Mu” [in which Zhao-zhou answers “Mu” (nothing/naught) when asked if a dog has the Buddha nature]. I had grappled with this kōan for some five years, even in the midst of my life in the navy. I recall that when Master Yamamoto first gave me this kōan, he said: “Be the genuine article, the real thing! Zen priests mustn’t rely on the experience of others. Do today what has to be done today. Tomorrow is too late!”

Master Yamamoto next assigned me the most difficult kōan of all, i.e., the sound of one hand. “The sound of one hand is none other than Zen Master Hakuin himself. Don’t treat it lightly. Give it your best!” the master admonished.

Inasmuch as I would soon be returning to my ship, Master Yamamoto granted me a most unusual request. He agreed to allow me to present my understanding of this and subsequent kōans to him by letter rather than in the traditional personal encounter between Zen master and disciple. This did not represent, however, any lessening of the master’s severity but was a reflection of his deep affection for the Buddha Dharma. In any event, I was able to return to my ship with total peace of mind, and nothing brought me greater joy in the navy than receiving a letter from my master.

|

Nakajima Genjō in naval uniform. |

War in China In 1937 my ship was made part of the Third Fleet and headed for Shanghai in order to participate in military operations on the Yangtze river. Despite the China Incident [of July 1937] the war was still fairly quiet. On our way up the river I visited a number of famous temples as military operations allowed. We eventually reached the city of Chenchiang where the temple of Chinshan-ssu is located. This is the temple where Kūkai, [9th century founder of the esoteric Shingon sect in Japan], had studied on his way to Ch’ang-an. It was a very famous temple, and I encountered something there that took me by complete surprise.

On entering the temple grounds I came across some five hundred novice monks practicing meditation in the meditation hall. As I was still young and immature, I blurted out to the abbot, “What do you think you’re doing! In Japan everyone is consumed by the war with China, and this is all you can do?” The abbot replied, “And just who are you to talk! I hear that you are a priest. War is for soldiers. A priest’s work is to read the sutras and meditate!”

The abbot didn’t say any more than this, but I felt as if I had been hit on the head with a sledgehammer. As a result I immediately became a pacifist.

Not long after this came the capture of Nanking. Actually we were able to capture it without much of a fight at all. I have heard people claim that a great massacre took place at Nanking, but I am firmly convinced there was no such thing. It was wartime, however, so there may have been a little trouble with the women. In any event, after things start to settle down, it is pretty hard to kill anyone.

After Nanking we fought battle after battle and usually experienced little difficulty in taking our objectives. In July 1940 we returned to Kure in Japan. From then on there were unmistakable signs that the Japanese Navy was about to plunge into a major war in East Asia. One could see this from the movements of the ships though if we had let a word slip out about this, it would have been fatal. All of us realized this so we said nothing. In any event, we all expected that a big war was coming.

In the early fall of 1941 the Combined Fleet assembled in full force for a naval review in Tokyo Bay. And then, on 8 December, the Greater East Asia War began. I participated in the attack on Singapore as part of the Third Dispatched Fleet. From there we went on to invade New Guinea, Rabaul, Bougainville, and Guadalcanal.

A Losing War The Combined Fleet had launched a surprise attack on Hawaii. No doubt they imagined they were the winners, but that only shows the extent to which the stupidity of the navy’s upper echelon had already begun to reveal itself. U.S. retaliation came at the Battle of Midway [in June 1942] where we lost four of our prized aircraft carriers.

On the southern front a torpedo squadron of the Japanese Navy had, two days prior to the declaration of war, succeeded in sinking the British battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse on the northern side of Singapore. Once again the navy thought they had won, but this, too, was in reality a defeat.

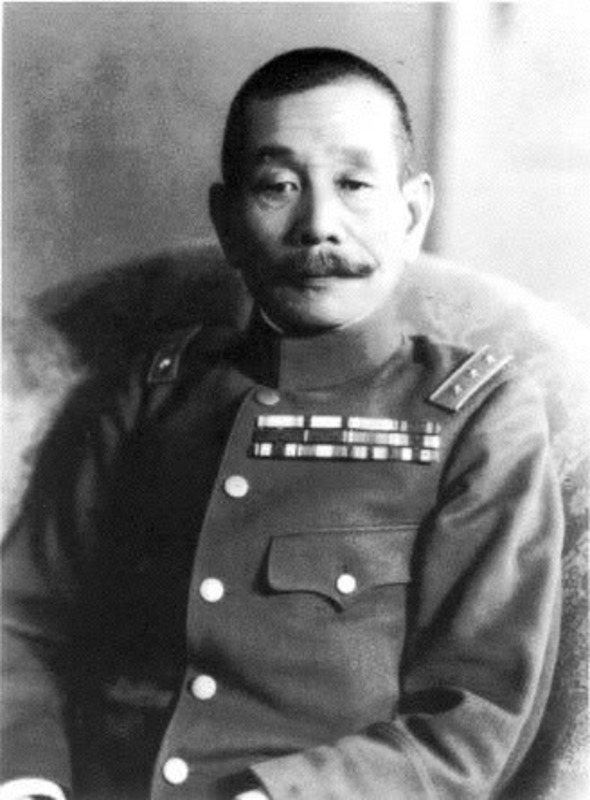

These two battles had the long-term effect of ruining the navy. That is to say, the navy forgot to use this time to take stock of itself. This resulted in a failure to appreciate the importance of improving its weaponry and staying abreast of the times. I recall having read somewhere that Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku [1884-1943], commander of the Combined Fleet, once told the emperor: “The Japanese Navy will take the Pacific by storm.” What an utterly stupid thing to say! With commanders like him no wonder we didn’t stand a chance.

|

Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku. |

In 1941 our advance went well, but the situation changed from around the end of 1942. This was clear even to us lower-ranking petty officers. I mean by this that we had started to lose.

One of our problems was that the field of battle was too spread out. The other was the sinking of the American and British ships referred to above. I said that we had really lost when we thought we had won because the U.S., learning from both of these experiences, thoroughly upgraded its air corps and made air power the center of its advance. This allowed the U.S. to gain air superiority while Japan remained glued to the Zero as the nucleus of its air wing. The improvements made to American aircraft were nothing short of spectacular.

For much of 1942 the Allied Forces were relatively inactive while they prepared their air strategy. Completely unaware of this, the Japanese Navy went about its business acting as if there were nothing to worry about. Nevertheless, we were already losing ships in naval battles with one or two hundred men on each of them. Furthermore, when a battleship sank we are talking about the tragic loss of a few thousand men in an instant.

As for the naval battles themselves, there are numerous military histories around, so I won’t recount them here. Instead, I would like to relate some events that remain indelibly etched in my mind.

Tragedy in the South Seas The first thing I want to describe is the situation that existed on the islands in the south. Beginning in 1943 we gradually lost control of the air as the U.S. made aerial warfare the core of its strategy. This also marked the beginning of a clear differentiation in the productive capacity of the two nations.

It was also in the spring of that year that my ship was hit by a torpedo off the coast of Hainan island. I groaned as I drifted in the South China Sea, caught in the realm of desire and hovering between life and death. Kōans and reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha were meaningless. There was nothing else to do but totally devote myself to Zen practice within the context of the ocean itself. It would be a shame to die here I thought, for I wanted to return to being a Zen priest. Therefore I single-mindedly devoted myself to making every possible effort to survive, abandoning all thought of life and death. It was just at that moment that I freed myself from life and death.

This freedom from life and death was in reality the realization of great enlightenment (daigo). I placed my hands together in my mind and bowed down to venerate the Buddha, the Zen Patriarchs, their Dharma descendants, and especially Master Yamamoto. I wanted to meet my master so badly, but there was no way to contact him. In any event, all of the unpleasantness I had endured in the navy for the past seven years disappeared in an instant.

Returning to the war itself, without control of the air, and in the face of overwhelming enemy numbers, our soldiers lay scattered about everywhere. From then on they faced a wretched fate. To be struck by bullets and die is something that for soldiers is unavoidable, but for comrades to die from sickness and starvation is truly sad and tragic. That is exactly what happened to our soldiers on the southern front, especially those on Guadalcanal, Rabaul, Bougainville, and New Guinea. In the beginning none of us ever imagined that disease and starvation would bring death to our soldiers.

As I was a priest, I recited such sutras as Zen Master Hakuin’s “Hymn in Praise of Meditation” (Zazen Wasan) on behalf of the spirits of my dying comrades. Even now as I recall their pitiful mental state at the moment of death I am overcome with sorrow, tears rolling uncontrollably down my cheeks.

Given the pitiful state of our marooned and isolated comrades, we in the navy frantically tried to carry them back to the safety of our ships. I recall one who, clutching a handful of military currency, begged us to give him a cigarette. Our ship’s doctor had ordered us not to provide cigarettes to such men, but we didn’t care. In this case, the soldier hadn’t even finished half of his cigarette when he expired. Just before he died, and believing that he was safe at last, he smiled and said, “Now I can go home.”

Another soldier secretly told me just how miserable and wretched it was to fight a war without air supremacy. On top of that, the firepower commanded by each soldier hadn’t changed since the 1920s. It was both heavy and ineffective, just the opposite of what the Americans had. Thus the inferiority in weapons only further contributed to our defeat.

It was Guadalcanal that spelled the end for so many of my comrades. One of the very few survivors cried and cried as he told me, “One morning I woke up to discover that my comrade had cut the flesh off his thigh before he died. It was as if he were telling me to eat it.”

There were so many more tragic things that happened, but I can’t bear to write about them. Forgive me, my tears just won’t let me.

Characteristics of the Japanese Military In the past, Japan was a country that had always won its wars. In the Meiji era [1868-1912] military men had character and a sense of history. Gradually, however, the military was taken over by men who did well in school and whose lives were centered on their families. It became a collection of men lacking in intestinal fortitude and vision. Furthermore, they suffered from a lack of Japanese Spirit and ultimately allowed personal ambition to take control of their lives.

In speaking of the Japanese Spirit I am referring to the August Mind of the great Sun Goddess, Amaterasu. Forgetting this, men in the military were praised as having spirit when they demonstrated they were physically stronger than others. This turned the Japanese Spirit into a joke!

Nevertheless, officers graduated from the naval academy thinking like this and lorded it over their pitiful subordinates. The officers failed to read those books so important to being human, with the result that by the end of the war the Japanese Navy had turned into a group of fools.

As for enlisted men, volunteers were recruited at such a young age they still hadn’t grown pubic hair on their balls. Gutless men trained these recruits who eventually became senior enlisted men themselves and the cycle repeated. And what was the result? A bunch of thoughtless, senior enlisted personnel! I was dumbfounded, for it meant the end of the Japanese Navy.

If only the officers at least had thoroughly read Sun-tzu’s Art of War and books on Western and Chinese history. If they had firmly kept in mind what they learned from such books it would have influenced their military spirit whether they wanted it to or not. How different things would have been had this kind of study been driven home at the naval academy.

If, prior to our invasion, a senior officer had taken six or so junior officers with him to thoroughly survey such places as New Guinea, Rabaul, Guadalcanal, etc. I don’t think they ever would have sent troops there. The same can be said for our naval attachés stationed abroad. Things would have been different had they thoroughly investigated the latent industrial and military potential of the countries they were assigned to.

The national polity of Japan is characterized by the fact that ours is a land of the gods. The gods are bright and like water, both aspects immeasurable by nature. Furthermore, they undergo constant change, something we refer to in the Buddha Dharma as a “mysterious realm.” Eternal and unbroken, these gods have existed down to the present-day. Stupid military men, however, thought: “A country that can fight well is a land of the gods. The gods will surely protect such a country.” I only wish that the top echelons of the military had absorbed even a little of the spirit of the real national polity.

The Japanese military of recent times was an organization that swaggered around in the name of the emperor. To see what it was like earlier, look at [army hero of the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5] Field Marshal Ōyama Iwao [1842-1916] from the Satsuma clan, the very model of a military man. Likewise, [naval hero of the Russo-Japanese war] Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō [1847-1934] was a true man of war.

I will stop my discussion at this point by tearfully acknowledging just how hellish the world was that these more recent stupid officers produced. Thus it is only with my tears that I am able to write these sentences, sentences I send to my beloved war comrades who now reside in the spirit world.

Final Comments This was a stupid war. Engulfed in a stupid war, there was nothing I could do. I wish to apologize, from the bottom of my heart, to those of my fellow soldiers who fell in battle. As I look back on it now, I realize that I was in the navy for a total of ten years. For me, those ten years felt like an eternity. And it distresses me to think of all the comrades I lost.

Author’s Remarks

Upon reading Nakajima’s words, I could not help but feel deeply disappointed. This disappointment stemmed from the realization that while Nakajima and I had earlier shed tears together, we were crying about profoundly different things. Nakajima’s tears were devoted to one thing and one thing only — his fallen comrades. As the reader has observed, Nakajima repeatedly referred to the overwhelming sadness and regret he felt at seeing his comrades die not so much from enemy action as from disease and starvation.

One gets a strong impression that as far as Nakajima is concerned what was ‘wrong’ about Japan’s invasion of China and other Asian countries was not the disastrous war that followed, but that, unlike its earlier wars, Japan had been defeated. Whereas previously, Japanese military leaders had been “men of character,” the officers of his era were a bunch of bookworms and careerists who had, moreover, failed to read widely in the art of warfare. The problem was not Japan’s invasion of China and other Asian countries, or atrocities committed in the name of liberating Asia, let alone its attack on the U.S., but that his superiors had recklessly stationed troops in areas, especially in the South Seas, that were indefensible once Japan lost air superiority.

While at a purely human level I can empathize with Nakajima’s sense of loss of his comrades, my own tears were not occasioned by the deaths of those Japanese soldiers, sailors, and airmen who left their homeland to wreak havoc throughout Asia and the Pacific. Rather, I had cried for all those, Japanese and non-Japanese alike, who so needlessly lost their lives due to Japan’s aggressive policies.

Nanking Massacre To my mind, the most frightening and unacceptable aspect of Nakajima’s comments is his complete and utter indifference to the pain and suffering of the victims of Japanese aggression. It is as if they never existed. The one and only time Nakajima refers to the victims, i.e., at the fall of Nanking, it is to tell us that no massacre occurred. Had Nakajima limited himself to what he, as a shipboard sailor at Nanking, had personally witnessed, one could at least accept his words as an honest expression of his own experience. Instead, he claims, without presenting a shred of evidence, that the whole thing never happened.

Yoshida Yutaka, one of Japan’s leading scholars on events at Nanking, described the Japanese Navy’s role as follows:

Immediately after Nanking’s fall, large numbers of defeated Chinese soldiers and civilian residents of the city attempted to escape by using small boats or even the doors of houses to cross the Yangtze river. However, ships of the Imperial Navy attacked them, either strafing them with machine-gun fire or taking pot shots at them with small arms. Rather than a battle this was more like a game of butchery.5

In addition, Japanese military correspondent Omata Yukio provides a graphic eyewitness account of what he saw happen to Chinese prisoners at Nanking lined up along the Yangtze riverbanks:

Those in the first row were beheaded, those in the second row were forced to dump the severed bodies into the river before they themselves were beheaded. The killing went on non-stop, from morning until night, but they were only able to kill 2,000 persons in this way. The next day, tired of killing in this fashion, they set up machine guns. Two of them raked a cross-fire at the lined-up prisoners. Rat-a-tat-tat. Triggers were pulled. The prisoners fled into the water, but no one was able to make it to the other shore.6

Needless to say, Nakajima was not the only Japanese military man to deny that anything like a massacre took place at Nanking. One of the commanders leading the attack on the city, Lt. General Yanagawa Heisuke (1879-1945), later dismissed all such allegations as based on nothing more than “groundless rumors.” His soldiers, he claimed, were under such strict military discipline that they even took care to wear slippers when quartered in Chinese homes.7

However, compare Gen. Yanagawa’s comments with those of his superior officer, General Matsui Iwane (1878–1948), commander of the Japanese Central China Area Army during the attack on Nanking. In the postwar period, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal found Matsui legally responsible for the massacre at Nanking and sentenced him to death. Shortly before his execution on December 23, 1948, Matsui made the following confession to Hanayama Shinshō, a Buddhist chaplain affiliated with the Shin (True Pure Land) sect at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo:

|

Matsui Iwane. |

I am deeply ashamed of the Nanking Incident. After we entered Nanking, at the time of the memorial service for those who had been killed in battle, I gave orders for the Chinese victims to be included as well. However, from my chief of staff on down no one understood what I was talking about, claiming that to do so would have a disheartening effect on the morale of the Japanese troops. Thus, the division commanders and their subordinates did what they did.

In the Russo-Japanese War I served as a captain. The division commanders then were incomparably better than those at Nanking. At the time we took good care of not only are Chinese prisoners but our Russian prisoners as well. This time, however, things didn’t happen that way.

Although I don’t think the government authorities planned it, from the point of view of Bushidō or simply humanity, everything was totally different. Immediately after the memorial service, I gathered my staff together and, as the supreme commander, shed tears of anger. Prince Asaka was there as well as theatre commander General Yanagawa. In any event, I told them that the enhancement of imperial prestige we had accomplished [by occupying Nanking] had been debased in a single stroke by the riotous conduct of the troops.

Nevertheless, after I finished speaking they all laughed at me. One of the division commanders even went so far as to say, “It’s only to be expected!”

In light of this I can only say that I am very pleased with what is about to happen to me in the hope that it will cause some soul-searching among just as many of those military men present as possible. In any event, things have ended up as they have, and I can only say that I just want to die and be reborn in the Pure Land.8

Numerous eyewitness accounts, including those by Western residents of the city, not to mention such books as Iris Chang’s 1997 The Rape of Nanking, provide additional proof of the widespread brutal and rapacious conduct of the Japanese military at Nanking if not throughout the rest of China and Asia. Thus, it borders on the obscene to have a self-proclaimed “fully enlightened” Zen master like Nakajima deny a massacre took place at Nanking even while admitting “there may have been a little trouble with the women.”

|

Chinese being beheaded at Nanking. |

In addition, compare Nakajima’s claim with an interview for the 1995 documentary film In the Name of the Emperor given by Azuma Shirō, the first Japanese veteran to publicly admit what he and his fellow soldiers had done in Nanking:

At first we used some kinky words like Pikankan. Pi means “hip,” kankan means “look.” Pikankan means, “Let’s see a woman open up her legs.” Chinese women didn’t wear underpants. Instead, they wore trousers tied with a string. There was no belt. As we pulled the string, the buttocks were exposed. We “pikankan.” We looked. After a while we would say something like, “It’s my day to take a bath,” and we took turns raping them. It would be all right if we only raped them. I shouldn’t say all right. But we always stabbed and killed them. Because dead bodies don’t talk.9

In attempting to explain the rationale behind the conduct of Japanese soldiers at Nanking, Iris Chang, among others, points to their religious faith as one of the key factors in making such conduct possible. She writes: “Imbuing violence with holy meaning, the Japanese Imperial Army made violence a cultural imperative every bit as powerful as that which propelled Europeans during the Crusades and the Spanish Inquisition.”10

From a doctrinal point of view, Japan’s Shinto faith cannot escape culpability for having turned Japan’s military enterprise into a “holy war.” That is to say, it is Shinto that asserted that Japan was a divine land ruled over by an emperor deemed to be a divine descendant of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu. Thus, any act sanctioned by this divine ruler must necessarily be a divine undertaking. Yet, as my book Zen At War amply demonstrated, this worldview was adopted in toto into the belief system of Japan’s Buddhist leaders, most especially those affiliated with the Zen school. Nakajima’s contemporary reference to Japan as a “land of the gods” is but further evidence that, at least as far as he is concerned, nothing has changed.

Pacifism Nakajima’s encounter with the Chinese abbot of Chinshan-ssu is, at least in terms of Buddhism, one of the most memorable parts of his memoirs, for it clearly reveals a head-on clash of values. On the one side stands Buddhism’s unconditional vow, required of both clerics and laity, to abstain from taking life. On the other side is the Japanese military’s willingness to engage in mass killing as an instrument of national policy. Nakajima was a Buddhist priest, yet he was also a member of the Japanese military. What was he to do?

“I felt as if I had been hit on the head with a sledgehammer,” Nakajima states before adding “as a result I immediately became a pacifist.” As promising as his dramatic change of heart first appears, nowhere does Nakajima demonstrate that it had the slightest effect on his subsequent conduct, i.e., on his willingness to fight and kill in the name of the emperor. This suggests that in practice Nakajima’s newly found pacifism amounted to little more than ‘feel good, accomplish nothing’ mental masturbation.

In fact, during a second visit to Shōinji in January 2000, I personally queried Nakajima on this very point. That is to say, I asked him why he hadn’t attempted, in one way or another, to distance himself from Japan’s war effort following his change of heart. His reply was short and to the point: “I would have been court-martialed and shot had I done so.” No doubt, Nakajima was speaking the truth, and I for one am not going to claim that I would have acted any differently (though I hope I would have). This said, Nakajima does not hesitate to present himself to his readers as the very embodiment of the Buddha’s enlightenment. The question must therefore be asked, is the killing of countless human beings in order to save one’s own life an authentic expression of the Buddha Dharma, of the Buddha’s enlightenment?

An equally important question is what Nakajima had been taught about the (Zen) Buddhist attitude toward warfare before he entered the military. After all, he had trained under one of Japan’s most distinguished Zen masters for nine years before voluntarily entering the navy, apparently with his master’s approval. Although Nakajima himself does not mention it, my own research reveals that his master’s attitude toward war and violence is all too clear.

As early as 1934 Yamamoto defended the deadly, terrorist actions of the “Blood Oath Corps” (Ketsumeidan) led by his lay disciple, Inoue Nisshō, In his court testimony Yamamoto justified the Corps’ killing of two civilian Japanese leaders as follows:

The Buddha, being absolute, has stated that when there are those who destroy social harmony and injure the polity of the state, then killing them is not a crime. Although all Buddhist statuary manifests the spirit of Buddha, there are no Buddhist statues, other than those of Buddha Shakyamuni and Amitabha, who do not grasp the sword. Even the guardian Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha holds, in his manifestation as a victor in war, a spear in his hand. Thus Buddhism, which has as its foundation the true perfection of humanity, has no choice but to cut down even good people in the event they seek to destroy social harmony. . . . Inoue’s hope is not only for the victory of Imperial Japan, but he also recognizes that the wellbeing of all the colored races (i.e., including their life, death, or possible enslavement) is dependent on the Spirit of Japan.11

Further, in November 1936 Yamamoto became the first abbot of a newly built Rinzai Zen temple located in Xinjing (J. Shinkyō), capital of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria. The main purpose of the temple, equipped with a meditation hall and known as Myōshinji Shinkyō Betsuin, was to serve as a “spiritual training center” (shūyō dōjo) for the Imperial Army. In this effort Yamamoto was aided by his close disciple, Nakagawa Sōen.12

If there is some truth to the old adage, “Like father, like son,” then one can also say, “Like master, like disciple.” Thus if Nakajima may be faulted for having totally ignored the moral teachings of Buddhism, especially those forbidding the taking of life, then he clearly inherited this outlook from Yamamoto, his own master. But were these two Zen priests, as well as Sawaki Kōdō in Part I, exceptions or isolated cases in prewar and wartime Japan?

In reality Nakajima and Yamamoto were no more than two representatives of the fervently pro-war attitudes held not only by Zen priests but nearly all Japanese Buddhist priests and scholars regardless of sectarian affiliation.

Furthermore, Nakajima’s preceding comments were not written in the midst of the hysteria of a nation at war, but as recently as 1999, more than fifty years later. This, of course, raises the possibility that Nakajima’s words reflect the way he wished his military service to be remembered rather than his thoughts at the time.

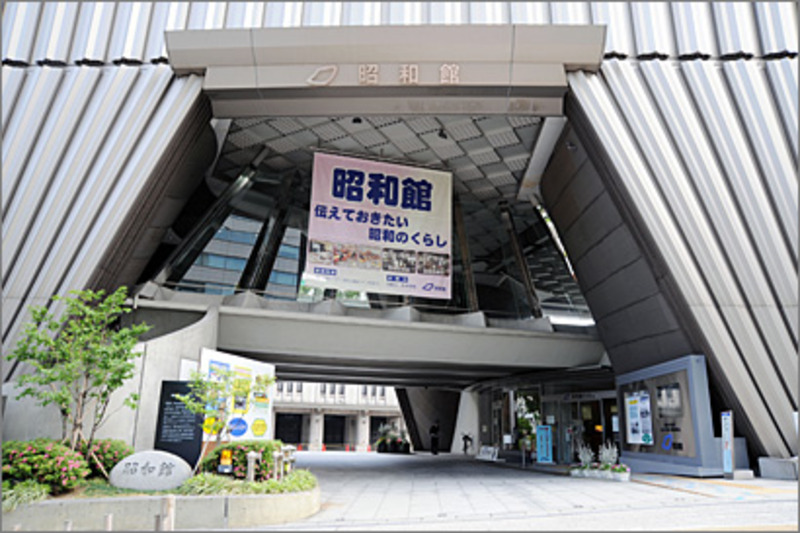

Like Nakajima, today’s Japanese political leaders still find it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to acknowledge or sincerely apologize for, let alone compensate the victims of, Japan’s past aggression. This fact was revealed once again in April 1999 when a new government-sponsored war museum opened in Tokyo. Known as the Shōwa-kan, this museum features exhibits devoted exclusively to the wartime suffering of the Japanese people themselves. The continuing attempt to deny the role of the Imperial military in the creation of wartime sex slaves, euphemistically known as “comfort women,” is but a further example.

|

Shōwa-kan. |

If there is anything that distinguishes Nakajima from his contemporaries, either then or now, it was his self-described conversion to pacifism in China. That is to say, Nakajima was at least conscious of a conflict between his priestly vows and his military duties. This was a distinction that very, very few of his fellow priests ever made. On the contrary, during the war leading Zen masters and scholars claimed, among other things, that killing Chinese was an expression of Buddhist compassion designed to rid the latter of their “defilements.”13

Conclusion

For those, like myself, who are themselves Zen adherents, it is tempting to assign the moral blindness exhibited by the likes of Nakajima and his master to the xenophobia and ultra-nationalism that so thoroughly characterized Japan up until 1945. On the other hand, there are those who describe it as reflecting the deep-seated, insular attitude of the Japanese people themselves.

While there is no doubt some degree of truth in both these claims, the possibility of a ‘Zen connection’ to this issue also exists. The Zen (Ch. Chan) sect has a very long history of ‘moral blindness,’ reaching back to its emergence in China. As the French scholar Paul Demiéville noted, according to the seventh century Chan text “Treatise on Absolute Contemplation,” killing is evil only in the event the killer fails to recognize his victim as empty and dream-like.14 On the contrary, if one no longer sees his opponent as a “living being” separate from emptiness, then he is free to kill him. Thus, enlightened beings are no longer subject to the moral constraints enjoined by the Buddhist precepts on the unenlightened.

Significantly, Chan’s break with traditional Buddhist morality did not go unchallenged. Liang Su (753-793), a famous Chinese writer and lifelong student of Tiantai (J. Tendai) Buddhism criticized this development as follows:

Nowadays, few men have true faith. Those who travel the path of Chan go so far as to teach the people that there is neither Buddha nor Dharma, and that neither good nor evil has any significance. When they preach these doctrines to the average man, or men below average, they are believed by all those who live their lives of worldly desires. Such ideas are accepted as great truths that sound so pleasing to the ear. And the people are attracted to them just as moths in the night are drawn to their burning death by the candle light.15 (Italics mine)

In reading Liang’s words, one is tempted to believe that he was a prophet able to foresee the deaths over a thousand years later of millions of young Japanese men who were drawn to their own burning deaths by the Zen-inspired “light” of Bushidō. And, of course, the many more millions of innocent men, women and children who burned with (or because of) them must never be forgotten.

An awareness of Zen’s deep-seated antinomianism may be helpful in understanding Nakajima’s attitudes as expressed in his recollections. It may, in fact, be the key to understanding why both Nakajima and his master were equally convinced that it was possible to continue on the road toward enlightenment even while contributing to the mass carnage that is modern warfare.

In Nakajima’s case it is even possible to argue that his experience of “great enlightenment” was actually hastened by his military service, specifically the fortuitous American torpedo that sank his second ship, the military fuel tanker Ryōhei, and set him adrift while killing some thirteen of his shipmates.16 Where else was he likely to have found both kōans and reciting the name of Buddha Amitabha “meaningless” and been forced, as a consequence, to “totally devote [him]self to Zen practice within the context of the ocean itself. . . . making every possible effort to survive, abandoning all thought of life and death.”

As Zen continues to develop and mature in the West, Zen masters like Nakajima remind us of a key question remaining to be answered — what kind of Zen will take root? The sexual scandals that have rocked a number of American Zen (and other Buddhist) centers in recent years may seem a world away from Zen-endorsed Japanese militarism. The difference, however, may not be as great as it first appears. I suggest the common factor is Japanese Zen’s long-standing and self-serving lack of interest in, or commitment to, many of Buddhism’s ethical precepts, especially the vow to abstain from taking life but also overcoming attachment to greed, including sexual greed.

If this question seems unrelated to Zen in the West, this is not the case. In addition to sex scandals, on July 5, 2010, a Zen priest once again provided meditation instruction to soldiers on the battlefield. This time, however, the instruction was provided by an American Zen priest, Lt. Thomas Dyer of the 278th Armored Cavalry Regiment and the first Buddhist chaplain in the U.S. Army. The meditation instruction Dyer provided was given to soldiers stationed at Camp Taji in Iraq.17

Dyer subsequently explained what Zen is within the context of Buddhism as follows:

Primarily Buddhism is a methodology of transforming the mind. The mind has flux in it or movement, past and future fantasy, which causes us not to interact deeply with life. So Buddhism has a methodology, a teaching and a practice of meditation to help one concentrate in the present moment to experience reality as it is. . . . Zen practice is to be awake in the present moment both in sitting and then walking throughout the day. So the idea is that enlightenment will come from just being purely aware of the present moment in the present moment.18

Just as in the writings of D.T. Suzuki and his Japanese contemporaries, the basic Buddhist precept to abstain from killing is conspicuously absent in Dyer’s description. Being “purely aware of the present moment” is, of course, a very desirable state of mind on the battlefield, especially when freed from questions of individual moral choice or conscience. Thus, the “wheel of the Dharma” as per Yamamoto Gempō’s description above is set to turn once again, only this time as an enabler of American military action.19

This is the second in a two part series.

See also

Brian Daizen Victoria, Zen Masters on the Battlefield (Part I)

Brian Daizen Victoria holds an M.A. in Buddhist Studies from Sōtō Zen sect-affiliated Komazawa University in Tokyo, and a Ph.D. from the Department of Religious Studies at Temple University. In addition to a 2nd, enlarged edition of Zen At War (Rowman & Littlefield), major writings include Zen War Stories (RoutledgeCurzon); an autobiographical work in Japanese entitled Gaijin de ari, Zen bozu de ari (As a Foreigner, As a Zen Priest); Zen Master Dōgen, coauthored with Prof. Yokoi Yūhō of Aichi-gakuin University (Weatherhill); and a translation of The Zen Life by Sato Koji (Weatherhill). He is currently a Visiting Research Fellow at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) in Kyoto. A documentary on Zen and War featuring his work is available here.

Recommended citation: Brian Daizen Victoria, “Zen Masters on the Battlefield (Part II)”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 27, No. 4, July 7, 2014.

Sources (Part II)

Chang, Iris. The Rape of Nanking. London: Penguin Books, 1998.

Ch’en, Kenneth. Buddhism in China. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964.

Demiéville, Paul. “Le Bouddhisme et la guerra,” Choix d’études Bouddhiques (1929-1970). Leiden: Brill, 1973.

Nakajima Genjō. Yasoji o Koete. Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture: Shōinji, 1998.

Onuma Hiroaki. Ketsumeidan Jiken Kōhan Sokki-roku, vol. 3. Tokyo: Ketsumeidan Jiken Kōhan Sokki-roku Kankō-kai, 1963.

Victoria, Brian. Zen At War, 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

_____. Zen War Stories, London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

Yoshida Yutaka. “Nankin Daigyaku-satsu o dō toraeru ka” (How to Grasp the Great Nanking Massacre?) in Nankin Daigyaku-satsu to Genbaku. Osaka: Tōhō Shuppan, 1995.

Notes

1 Note that this branch of the Rinzai Zen sect was established by Nakajima himself and has never been formally recognized as an independent sub-sect by the other branches of the Rinzai sect.

2 The Rinzai sect had first been forced to unify into one administrative organization by the wartime Japanese government. In the immediate aftermath of the war the Rinzai sect remained unified for the first year during which time it was headed by Yamamoto Gempō.

3 The Myōshinji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect did not offer its war apology until September 27, 2001. For details, see Victoria, Zen at War 2nd ed., pp. ix-x. On the other hand, the Sōtō Zen sect had first published its war apology in 1993. For details, see Victoria, Zen at War, pp. 153-56.

4 Nakajima’s war memoirs are primarily contained Yasoji o Koete, pp. 41-68.

5 Yoshida, “Nankin Daigyaku-satsu o dō toraeru ka” (How to Grasp the Great Nanking Massacre?) in Nankin Daigyaku-satsu to Genbaku, p. 128.

6 Quoted in Chang, The Rape of Nanking, p. 48.

7 Ibid, p. 176.

8 Quoted in Victoria, Zen War Stories, p. 187.

9 Ibid., p. 49. Note that the romanized Chinese here, as in other places, has been converted to pin-yin format from Wade-Giles. The original read “Pikankan.” While it is impossible to say for certain without seeing the original Chinese characters, the word “pi” (bi) can refer to a woman’s vagina. Given the context, this (rather than “hip”) is the more likely meaning of the term used by Azuma and his fellow soldiers.

10 Ibid., p. 218.

11 Quoted in Onuma Hiroaki, Ketsumeidan Jiken Kōhan Sokki-roku, vol. 3, p. 737. For a more detailed description of the “Blood Oath Corps” and Yamamoto Gempō’s connection to it, see Victoria, Zen War Stories, pp. 207-218.

12 For further details concerning both Yamamoto Gempō and Nakagawa Sōen’s wartime record, including alleged “anti-war” activities, see Victoria, Zen War Stories, pp. 92-105.

13 See Victoria, Zen At War, pp. 86-94, for further discussion of this point.

14 For further details, see Demiéville, “Le Bouddhisme et la guerra,” Choix d’études Bouddhiques (1929-1970), p. 296.

15 Quoted in Ch’en, Buddhism in China, p. 357. Liang Su was an important figure in Chinese intellectual and literary circles during the last quarter of the eighth century. He was among the first to recognize the possibility of a synthesis of Buddhism and Confucianism that eventually led to the creation of Neo-Confucianism. Liang studied Tiantai (J. Tendai) Buddhism under the guidance of Chanjan (711-782) who revived this school in the late eighth century.

16 Nakajima provided the name of his torpedoed ship and estimated casualties in a second personal interview that took place at Shōinji on January 25, 2000. Of special interest is the fact that the Japanese ship that first rescued Nakajima was itself torpedoed shortly thereafter, and Nakajima found himself in the water yet again. It was his good fortune, however, to have been rescued a second time.

17 A 2010 YouTube video of Lt. Thomas Dyer providing meditation instruction to US soldiers stationed at Camp Taji, Iraq is available here.

18 (Now Capt.) Thomas Dyer’s explanation of Zen and Buddhism is available here.