The Bodies in the Academy

In 1957, a young Japanese writer published a collection of short stories which quickly attracted nationwide attention. The title of the collection – Shisha no Ogori – is particularly difficult to render into English, but has been translated by John Nathan as Lavish Are The Dead. The writer was Ōë Kenzaburō, and the success of this, his first published book, was the start of a career that would ultimately bring him international fame and a Nobel Prize for literature1

The title story of Lavish Are The Dead is a surreal tale of a young man who, like Ōë himself, is a student of French literature at the University of Tokyo. To earn a little money, the student takes a job looking after dead bodies that are stored, floating in vast pools of preservative beneath the university’s Medical Faculty, awaiting dissection. As he works with these bodies, the student enters into mental conversations with the dead, who include soldiers and civilians killed more than a decade earlier in the Pacific War:

I saw the bullet wound in the soldier’s side; it was shaped like a withered flower petal, darker than the skin around it, thickly discoloured.

Do you remember the war? You must have been just a child?…

What it amounts to is that I was carrying your hopes on my shoulders. I guess you’ll be the ones who dominate the next war.2

Ōë’s fable can be read in many ways. Viewed through one prism, it is a reflection on the forgetting of the Pacific War, whose whispering corpses float beneath the surface of national memory, just as the dead of the story float in their subterranean tanks beneath the halls of Japan’s intellectual establishment. But Lavish Are The Dead, both in its subject matter and its silences, can also be read as a strangely powerful metaphor for the submerged presence of the Korean War in Japanese society, culture and memory.

In this essay, I explore the metaphorical and real presence of the bodies of the dead in Japan during the Korean War era, and use this exploration as a starting point for reconsidering the memory of the Korean War in Japan. Narratives of Japan’s relationship to the Korean War, both in popular memory and in many historical studies, have been dominated by the theme of the Korean War boom – cynically described by then Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru as a ‘gift from the gods’ – and its impact on Japan’s postwar economic growth. Many studies of the period cite Chalmers Johnson’s comment that the Korean War was ‘in many ways the equivalent for Japan of the Marshall Plan’.3 Other historians have emphasized the political impact of the war in influencing the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty and hastening the process of Japanese rearmament, and some also point out that Japan did in fact send minesweepers and other support to the war zone.4 But, partly perhaps because the personal stories of Japanese involved in the war have seldom been told, even these narratives tend often to remain oddly abstract and bloodless, failing to capture the physical dimension of the violence of war, from which Japan was not immune.

A focus on the physical presence of bodies – both living and dead – also makes visible two other important dimensions of the Korean War and Japan’s connections to its violence. The first is the centrality of the issue of race. The spectre of race haunted the war, most obviously, perhaps, in the emergence of US stereotypical images of Asians which would be carried over to later conflicts in Vietnam and elsewhere.5 But race in the Korean War had complex and multilayered dimensions that go beyond simple dichotomies between “white” and “Asian”, and many of these dimensions were, as we shall see, uncomfortably evident in Korean War era Japan.

Secondly, a focus on the physical and corporeal realities of the war highlights the deep regional differences in Japan’s experience of the Korean War. The tendency to view Japan’s Korean War history in abstract and economic terms is, I shall suggest, closely linked to the tendency to view Japanese history from the perspective of Tokyo. The capital indeed reaped the economic benefits of the war, while remaining relatively unaffected by the physical pain and social disruption that it generated. But, for many of Japan’s regional port cities, particularly for the ports of Kyushu, the impact of the war was very different. It was here that both the violence of war and its complex racial dimension became much more clearly visible.

History as Myth

Ōë Kenzaburō entered Tokyo University in 1953, shortly before the Panmunjom Armistice put an end to the immediate violence of the Korean War (though without producing a lasting peace settlement). Other than the ambiguous reference to ‘the next war’, there is no mention of the Korean War in Lavish Are The Dead. It is not clear whether his fable of a student’s encounter with the war dead arose spontaneously from Ōë’s fertile imagination, or whether it was in part inspired by stories heard from his fellow students. There is a dream-like quality to the student’s movements as he shifts back and forth between the surface world of an economically booming Tokyo and the world of the dead that lies silent and invisible beneath. The smell of death permeates his body, and he becomes unable to connect with the living, as though separated from them by some invisible membrane.

The Japanese version of Wikipedia cites Ōë’s story as the source of a widespread Japanese urban myth: the myth that university students and others were employed, and paid substantial wages, to prepare dead bodies for medical dissection, or to embalm the bodies of dead US soldiers sent back from the war fronts in Vietnam and elsewhere. There is, Wikipedia tells us, no basis to this myth.6 Nishimura Yoichi, a prominent Japanese forensic surgeon and popular writer, devotes an entire chapter of his 1995 memoirs to the ‘troublesome rumour’ [komatta uwasa] that Japanese were employed in the morgues of US army bases to piece together the dismembered bodies of American war dead. This rumour, he says, ‘began particularly around the time of the Korean War, and flared up again later during the Vietnam War’. ‘Now,’ he continues, ‘this stupid myth no longer exists. But the rumour, probably woven together from the reality that bodies were dissected for autopsies and a random fascination with the bizarre, seems to have remained deeply rooted for years and to have been depicted in many different forms’.7

As Jan Harold Brunvand observes in his study The Vanishing Hitchhiker, urban myths contain a certain metaphorical truth, expressing social concerns and fears in symbolic form.8 Brunvand’s reflections on this subject have left me wondering – if legends reveal submerged social anxieties, what aspects of shared memory cause historical facts to be consigned to the realms of urban myth? For, despite the comments of Nishimura and of Wikipedia, the story of Japanese students and the bodies of the war dead is not a myth that has been remembered as historical fact, but rather a historical fact that has been remembered as myth. In the years just before Ōë wrote Lavish Are The Dead, Japanese labourers and some university students were indeed being recruited to help process some 30,000 bodies of American war dead which flowed through Japan during the Korean War9, but public memory seems reluctant to absorb this reality, consigning it instead to the floating world of fiction and fantasy.

Among the students employed for this task was Hanihara Kazurō, who published an account of his experiences in 1965. Hanihara had just graduated in anthropology from Tokyo University and was about to start postgraduate research when, in April 1951, he and at least one other anthropology postgraduate from the same university, Furue Tadao, were recruited by the US military and sent to Camp Jōno in the southwestern city of Kokura to help reassemble and identify the dismembered remains of US servicemen sent back from the Korean front.10 The students’ employment with the American Graves Registration Service Group was endorsed by an official contract between the US military and Tokyo University, signed by the Dean of the university’s Science Faculty, Kaya Seiji.11

At the Jōno base, the young Japanese anthropologists worked alongside American experts and a team of Japanese labourers brought in to perform the menial tasks of transporting the remains and cleaning the morgue: a place every bit as strange and macabre as the subterranean world depicted in Oë’s short story. On busy days, the students examined as many as sixty to eighty corpses a day, most of them severely decomposed because they had been temporarily buried where they fell when US troops retreated before the onslaught from the north, and then unearthed and sent to Japan when the tides of war turned. In words which echo the language of Oë’s story, Hanihara vividly evokes the stench of death which hit the workers when they first entered the morgue, and which clung to their clothes and bodies throughout their time in Kokura. And yet, for him, the work had benefits: it was, he felt, a unique opportunity for practical study of the physical anthropology of people of many different races. ‘One thing was for sure’, he wrote, ‘now and probably even in the future it would be most unlikely that we would ever have another chance to examine the bones of hundreds of white people and black people’; and, as it turned out, not only of black and white, but also of Hispanics, Native Americans, Asian Americans and people of mixed race.12

|

Camp Jono, Kokura, Japan |

The Korean War was, of course, a world war in miniature. To boost the ‘global’ image of the UN forces, the United States secured the participation of Thais and Ethiopians, Turks and Colombians. The war also took place at a time when the early stirrings of civil rights activism were beginning to be heard in the United States. It was, then, not only a multi-racial war but also one shadowed by uneasy racial consciousness. This seems indeed to have been one of the reasons why Hanihara and at least two other Tokyo University anthropology postgraduates were brought in to work at the morgue. A report by the US military published just after the Korean War recalled (with a slight re-adjustment of the facts):

Our anthropologists included two Americans; one European, who had extensive experience in the World-War-II program; and one Japanese, who was a professor from a leading university in Japan; each highly trained in his specialized profession. In fact, all of the major races of mankind were represented among this small group of experts who performed the anthropological work, a highly desirable but extremely unusual situation. A number of indigenous [i.e. Japanese] workers were also employed to perform such highly important tasks as cleaning and scrubbing our facilities so that we might maintain the high standards of sanitation essential to the success of the project.13 Hanihara went on to become one of Japan’s best-known physical anthropologists, famous particularly for his enthusiastic quest for the racial origins of the Japanese.

Mobile Bodies

The history of the Camp Jōno morgue thus makes us see the war, not in terms of abstract economic indicators, but in terms of human bodies – the bodies of the dead and the living that move between Japan and Korea, and interact in complex and sometimes surprising ways. Throughout the war, Japan and Korea were constantly linked by an unceasing and massive movement of people. In all around 1.8 million Americans, some 90,000 British Commonwealth troops, and thousands of other soldiers from eleven other countries serving under the UN Command, fought for varying lengths of time in the Korean War, and almost all spent some time in Japan on their way to and from the conflict. Many moved repeatedly back and forth between Korea and Japan. Some ‘commuted’: most US and Commonwealth pilots serving in the war ‘enjoyed a “normal” home life in Japan when they finished daily duty. They flew out in the morning to bomb Korean targets and returned to American bases in Japan in the evening’.14 Tens of thousands of war wounded, including seriously injured prisoners of war, were airlifted to Japan for treatment in hospitals in Kyushu, Osaka and Tokyo: more than 9,000 war casualties were flown to hospitals in southern Japan in one six-week period from October-November 1950 alone.15

The flows of people were multidirectional, multiracial, and multinational. Around 1,700 Filipino workers were brought to Okinawa by the US military and by defense contractors such as the Vinnell Corporation at the height of the Korean War.16 One Japanese sailor who worked on vessels carrying UN troops and supplies between Yokohama and the Korean War front was astonished to find himself working alongside a multicultural crew whose members included not only Latino, Asian and African Americans but also Malays, Indonesians and Scandinavians.17

And then, of course, there was the movement of Japanese and Koreans themselves between the two countries. Japan, which was under allied occupation until April 1952 and was not a member of the United Nations, was officially uninvolved in the military conflict. In practice, though, it is estimated that over 8,000 Japanese people were sent to the Korean War zone in military related-roles.18 644 ethnic Koreans living in Japan also volunteered for service in Korea via the pro- South Korean community organization Mindan, and were trained in US bases in Japan before being dispatched to the war zone. The flow in the opposite direction included 8,625 Korean recruits to the KATUSA (Korean Augmentation to the United States Army) scheme, who were sent to join the US 7th Infantry Division at its base in Japan. Many of these were young men rounded up more or less at random from the streets of Busan: ‘in the contingents shipped to Japan, schoolboys still had their schoolbooks; one recruit who had left home to obtain medicine for his sick wife still had the medicine with him.’19

Other more shadowy arrivals and departures are yet to be fully documented. A few prisoners-of-war captured by UN forces were apparently transferred from Korea to Tokyo for questioning, though few Japanese or US official documents refer to this fact.20 Thousands of Korean war refugees also fled the violence of war to Japan, but since the allied occupation authorities and Japanese government refused to allow them official refuge in Japan, they arrived clandestinely on people- smuggling boats which dropped them off at remote spots along the coast under cover of darkness.21

Though Japanese were not officially called on to give their lives in the war, they were encouraged to make a different kind of physical contribution. In November 1950, the Japan Blood Bank was established, apparently at the request of the American occupation authorities, to coordinate Japanese donations of blood to the UN forces in Korea. The Japan Red Cross Society also made appeals for blood donations for the war wounded. By the beginning of 1953, thousands of Japanese had donated (or more often, sold) blood, which was collected and flown to the Korean front in special nighttime cargo flights.22

The Silence of the Bones

While the transport planes were conveying this life-saving cargo to Korea, a far more massive seaborne operation was underway to return the remains of the American war dead via Japan to the United States. A wartime report reveals the magnitude and uniqueness of the task:

never in the history of the United States, or of any other nation, has there been a mass evacuation of the remains of men killed in action while hostilities were still in force. The departure from the long established practice of leaving remains in battlefield cemeteries or isolated locations until after the cessation of hostilities necessitated the activation of an organization capable of carrying out the manifold operations of receiving, processing, identifying, embalming, casketing, and shipping.23

The decision to take on this herculean task seems to have reflected uncertainties about the eventual outcome of the war. During the first weeks of combat, fallen US soldiers had been buried in ground quickly overrun by advancing North Korean forces. After the Incheon Landing of September 1950, as South Korean and UN forces pushed northward, American war dead buried in recaptured ground were disinterred and moved to new cemeteries. But then China entered the war and the tide of combat turned again. It was at this point that a decision was taken to repatriate the bodies of US war dead via Japan while the war was still continuing.24 This operation to bring home the dead was restricted to US servicemen: dead soldiers from other forces under the UN command were buried in a giant new cemetery at Danggok near Busan (where some US servicemen were also temporarily buried, awaiting removal to Kokura and thence to the US).25

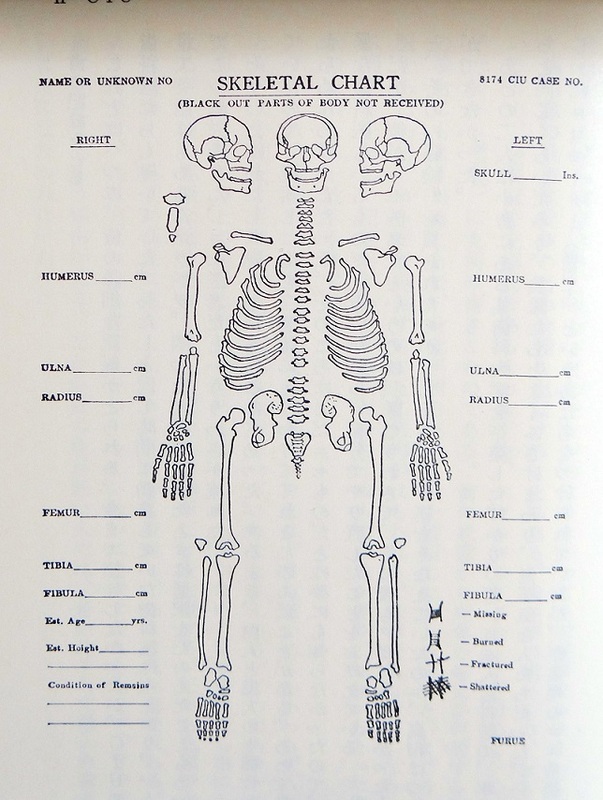

The first ship bearing the remains of the dead arrived in the port of Kokura on 3 January 1951, and by the time anthropology student Hanihara Kazurō arrived at Camp Jōno in April of that year, the bodies of some 16,000 soldiers had passed through the Jōno morgue.26 Unlike Ōë Kenzaburō’s fictional student, Hanihara did not engage the dead in conversation. Instead, he observed them with an eager but detached and scientific eye, meticulously measuring bones, identifying racial characteristics and filling in the standardized diagram of a human skeleton to be completed for each body. (The instructions on the diagram read, ‘black out parts of body not received’).27

|

Unloading bones at Kokura |

In the book he later wrote about his experiences, Hanihara carefully catalogued the physical differences between the races on an evolutionary scale that placed the ‘black race’ closer to the animal kingdom than the ‘white’: indeed he expressed some pride in having developed such a sharp eye for racial distinctions that ‘provided they were prototypical, I could tell a white person’s body from a black person’s even at two meters distance, and even if there was nothing there but a lower jaw-bone’.28 The presence of a large number of mixed race bodies troubled him, though, particularly since many soldiers who were labeled ‘Negro’ on their army records should clearly, according to his notions of proper anthropological classification, have been labelled ‘mixed blood’.29

|

Skeletal chart used at Camp Jono Morgue |

Even so, Hanihara’s account of his work in Kokura has its moments of unconscious pathos. He recalls the one and only time he was called on to determine whether human remains from the war front were those of a man or a woman. Since all US combat troops at that time were men, it was rarely necessary to determine the sex of the dead. In this case, though, Camp Jōno received the partial remains of a person probably killed by a mine and, on close inspection, the morgue’s scientists decided that these must be the remains of a Korean whose body had accidentally become mixed up with those of American servicemen. This left open the question of whether the body was that of a Korean soldier, or of a civilian caught up in the fighting. It was determined, in the end, that the body was that of a man, but the bones (of course) gave no hint whether this was a soldier or a civilian, a man from the North or the South, a communist or anti-communist or a person utterly indifferent to ideology. Hanihara also does not tell us what happened to the bones in the end.30 We are left only with the sense of the terrible loneliness of a human life that ended, nameless and unidentifiable in a foreign land, exposed to the anthropometric scrutiny of total strangers.

Hanihara entitled his memoir of Camp Jōno ‘Reading the Bones’ [Hone o yomu]. The bones laid out on the tables at Kokura were, to him, entirely legible, transparently revealing their race, their age, and at times (through dog tags and record-matching) their names and serial numbers. But the bones, though legible, do not speak. They tell no stories. Their lost lives remain infinitely silent.

The Ghost Ships

One evening, after finishing his work in the morgue, Hanihara Kazurō left the inn where he was staying in Kokura and walked down to the Sunatsu River, which flows to the west of the town centre into the narrow straits separating the islands of Kyushu and Honshu. Kokura at this time was a small city of around 200,000 people, though during the first half of the twentieth century, it had been one of Japan’s most important ports: like the neighbouring port of Moji, Kokura was perfectly situated to provide access to the Korean Peninsula, and through Korea, to Japan’s empire in Asia. The city had also been the intended target for the second American atomic bomb. It had been spared only by a local blanket of clouds which covered the town on the morning of 9 August 1945, making it impossible for the US pilots to find their target. They flew southward and dropped the bomb on Nagasaki instead.

With the loss of Japan’s empire, the nation’s centre of economic gravity had shifted eastward, to Pacific coast ports like Yokohama, but the outbreak of the Korean War had again transformed the economic and strategic landscape, and with it, the landscape of Kokura.

At the mouth of the Sunatsu River (writes Hanihara) I turned left, and, glancing towards the sea that could be glimpsed through the gaps between the warehouses, stopped dead in my tracks. A ship far bigger than anything usually seen in this little harbour was approaching the wharf. Straining my eyes, in the bluish moonlight I could make out the Stars and Stripes fluttering on the ship’s stern…

The ship came to a stop about a hundred metres from the place where I was standing. At that point barbed-wire entanglements had been put in place, so I could get no closer. I guess the ship must have come from somewhere around Busan. It was strangely quiet. I could just see a few people who appeared to be American soldiers on the shore, but there was no one on the deck of the ship. It was like a ghost ship. At length, there was a great clattering sound and a splash of water near the ship’s bow. It had dropped anchor.

Again, all was still. Then the American soldiers on shore shouted something, but I could not understand what they were saying. Just as I was thinking of turning back, suddenly the bow of the ship began to move. A vast doorway appeared, as though the ship’s bow was gaping open its mouth. Out from this mouth, like a tongue, came a gangway that extended to the wharf.31

The next day, when he went to work, Hanihara was approached by a middle- aged Japanese morgue cleaner who told him, ‘a whole lot more bodies from Korea arrived yesterday. The trucks were going past all night, so it was really noisy… Looks like it’s going to get busy again’. The shipments of dead from Korea often arrived at night, and Hanihara believed that this was done to prevent their arrival from being observed by citizens of Kokura, who might have drawn pessimistic conclusions about the course of the war from the sight of the great number of American dead returning from the Korean front.32

But the cover of darkness could not prevent the ghost ships from casting a pall over the town. As historian Ishimaru Yasuzō writes, ‘the horrors of war such as the mass escape of US soldiers and transportation of the bodies of soldiers who were killed on the Korean Peninsula were deeply affecting the people who lived around Kokura Port and Moji Port’.33 The ‘mass escape’ in question took place soon after the start of the war, on 11 July 1950, when some 200 soldiers from the US 24th Infantry Regiment, on their way to the Korean War front, staged a breakout from Camp Jōno, and descended on the centre of Kokura, smashing shop windows, assaulting women and engaging in fights with local people. One Japanese man was shot dead in the riot, several were injured and, according to the recollections of the then mayor of Kokura, Hamada Ryōsuke, about 28 women were raped.34

The Specter of Race

At that time, the US military was gradually moving towards policies of racial integration, but widespread segregation remained. The 24th Infantry Regiment, though under the control of white commanding officers, was an all-black regiment whose members had been in Japan ever since the start of the occupation. They had been stationed in rural Gifu Prefecture, where conditions had been pleasantly peaceful, but throughout their time in Japan had faced repeated instances of racial prejudice in their interactions with other occupation force military units and with some members of the Japanese public. On the outbreak of the Korean War, the troops of the 24th Infantry Regiment had been hopeful that they would not be sent to the Korean front, since most members of the regiment had little combat experience. They were also very poorly equipped for combat; and some surely shared the doubts expressed by 1st Lt. Beverley Scott of the 1st Battalion, who pondered why black Americans like himself should ‘give up their lives for the independence of South Korea when they themselves lacked full rights at home’.35

The departure of the 24th Infantry Regiment to Korea was chaotic. The soldiers were supposed to sail from Sasebo, but were instead diverted to Camp Jōno, where there was inadequate accommodation to house them. From there, as they discovered, they were to be shipped to Korea in a hastily assembled flotilla of ‘fishing boats, fertilizer haulers, coal carriers and tankers’.36 It was against the background of this chaos, as the miseries of their situation and the prospect of impending death confronted the soldiers, that the mass breakout and riot occurred. Although those involved were only a small fraction of the three thousand members of the regiment, from the point of view of the citizens of Kokura the riot was a traumatic introduction to the realities of the Korean War and American society. The rioters were rounded up by other members of the regiment and dispatched the next day to the battle front. A cursory investigation by the US military concluded with an official declaration that no one had been killed or injured, and the Kokura Riot was then largely written out of the history of Japan in the Korean War.37 In the context of Japan’s deepening security ties with the US, neither the American nor the Japanese government wanted to probe the sensitive issues of racial discrimination and violence against women raised by the riot, and occupation era censorship ensured that it received little publicity in the Japanese media.

Meanwhile, in their first six weeks in Korea the 24th Infantry Division suffered 883 battle casualties.38 Many of those who had passed through Camp Jōno on their way to Korea returned to the camp in the ghost ships, to be laid out on its bleak antiseptic tables where even in death – even in the effort to return their bodies to their families – their mortal remains were viewed through the prism of the race that had overshadowed their lives.

The Landscapes of Japan’s Korean War

The stories of the ghost ships and the Kokura riot illustrate the direct connection of Japan to the violence of war; they also make visible the geographically uneven effects of the war on different regions of the country. The contrast between towns like Kokura and central Tokyo was striking. Tokyo, of course, was also intimately connected to the war, but in very different ways. The United Nation’s engagement in Korea was being commanded from the Dai-Ichi Building, just across the road from the imperial palace in the heart of the Japanese capital. The presence of the war’s nerve centre in Tokyo brought with it an influx of other war-related activities. Foreign journalists covering the war congregated in Tokyo, since this was where the UN command gave its press briefings; so too did the offices of international agencies engaged in war related activities, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross. These command, control and information gathering activities, and the crowds of foreigners they attracted to Tokyo, gave the city a rather fevered vivacity, captured in words by US journalist Hanson Baldwin:

Tokyo is a city of glaring contrasts; we, the conquerors, live high, wide and handsome; parties, dinners, dances and flirtations provide a silver screen obscuring but never completely hiding the grim background of Korea. There is sometimes almost a frenetic gaiety… The silver gleams; the cocktails are good; the wines are vintages; the liquers are numerous and the uniforms shine in the candlelight; at the door, the kimono-clad servants lined up in a row bow profoundly to the departing guests.

But in the Dai-Ichi building, headquarters of SCAP (Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers) the lights shine far into the night and are reflected in the turgid waters of the moat surrounding the Imperial Palace.

At a Japanese dinner, as the geisha fills the little cups with sake, a Japanese newspaper man says: ‘A retired general told me we would need a minimum of eighteen divisions – several of them armored – to defend Japan.39

Swiss photographer Werner Bischof, who lived in Japan from 1951 to 1952, captured the mood in his photographs of Tokyo: the jumble of new buildings and advertisement hoardings obscuring the bomb scars of the Pacific War, the smartly clad young women striding through the streets of Ginza, the earnest students debating politics over cups of coffee and perusing the works of Picasso at an art exhibition.40 (See Bischof’s photos at the website www.magnumphotos.com). From the perspective of central Tokyo, it was easy enough to see the war as an abstract and disembodied phenomenon whose effects on Japan were overwhelmingly economic and wholly beneficial. But in port cities like Yokohama, Kokura, Moji and Sasebo, the feel of war was very different.

Large parts of their harbours were sealed off by barbed wire barriers (like those described by Hanihara), making them inaccessible to local fishing fleets and commercial vessels, many of which had in any case been mobilized to carry troops and supplies to the war front. In Moji, for example, the Tōzai Steamship company supplied 120 small commercial vessels and their crews to the UN command to support the Incheon Landing.41 Military vehicles constantly rumbled through the streets, and the superstructures of huge troop transports towered over the dockside warehouses. Bischof traveled throughout the country and as far as Okinawa, which was under separate and direct US military occupation and, like the port cities of western Japan, was utterly transformed by the outbreak of the war. There huge construction projects, mostly carried out by large Japanese corporations, created a landscape of tar and concrete, barracks and aircraft hangers on land confiscated from local farmers. In Okinawa, Bischof photographed the giant B-29 bombers which roared down newly-constructed runways on their bombing missions to Korea, the UN logos on their sides surrounded with symbolic images of the torrent of bombs they had dropped on the enemy.

The backstreets of Tokyo, to be sure, were dotted with the bars, strip clubs and brothels that flourish on the periphery of war – Bischof captured one particularly haunting image of the entrance to a Tokyo strip club, where the booted, uniformed legs of a partly visible US soldier loom over the small form of the recumbent woman within. But in the port towns of regional Japan and the base towns of Okinawa, with their much smaller populations, the large red light districts that sprang up in the shadow of the war had a far more visible and socially overwhelming impact than they did in a metropolis like Tokyo.42

The War on the Docks

In places like Kokura, though the war certainly brought economic growth and employment, it was no ‘gift from the gods’; instead, it was something very much more complex, more physical and more filled with pain. There was another reason, too, why the war had greater immediacy in such regional and coastal towns. Places like Kokura and Moji had large populations of Korean migrants. Some had been brought there as labourers during the war. Others had been living elsewhere in Japan in colonial times, and had drifted to the ports after Japan’s defeat in the war, seeking ships to take them home to Korea, but had become stranded in Japan because they lacked the means to leave. Others again had crossed to Korea after its liberation from colonial rule only to discover that there was no work and housing for them there, and had returned on people-smuggling boats to Japan’s west coast and found work as day labourers on the docks. It is estimated that in the 1930’s about 20% of dock labourers in the ports of the Shimonoseki-Moji area were Korean.43 The figures for the early 1950s are uncertain, but were certainly large.

The Korean War was played out in miniature within the Korean community in Japan. While the pro-South Korean organization Mindan recruited volunteers to fight on the Southern side, the pro-North Korean United Democratic Front of Koreans in Japan [Zainichi Chōsen Tōitsu Minshu Sensen, or Minsen for short] collaborated with Japanese communists in staging covert sabotage actions aimed at preventing the transport of US/UN troops and supplies from Japan to Korea. Many of these guerrilla acts were carried out in the port cities where ships to Korea were loaded and unloaded. On the docks of Yokohama, Sasebo, Kokura and Moji a miniature and invisible Korean War was being waged, as pro-communist dockworkers quietly and systematically damaged the tanks and guns they were loading into transport vessels, or ‘accidentally’ dropped military hardware into the murky waters of the harbour.44

But as historian Ōno Toshihiko discovered in his interviews with Koreans who had worked on the Moji docks during the Korean War, the struggles of everyday life left many with little time to engage with the politics of war. The outbreak of the war had aggravated the fear and prejudice that already severely restricted job opportunities for Koreans living in Japan. Agonizingly aware of the impact of the war on their homeland and on relatives still in Korea, many simply did what they had to do to survive, seizing the chance to labour through the night, loading military hardware onto the great military transports in return for the casual wages available to day labourers. One Korean former dockworker recollects that he had been, in his own words, so busy with the struggle for subsistence that he was capable only of thinking ‘whichever side wins, the war will end’. Another recalls, ‘we knew that those tanks and things, when they were sent over there [to Korea], were going to be used to kill people, but what else could we do? If we didn’t load them, we wouldn’t have had any work.’45

Embodying Procurements

Through the symbolism of Lavish Are The Dead, Oë Kenzaburō probed the repression of the past: the concealment of the violence of war, the forgetting of lost lives, the segregation of the dead from the living. For much of the past sixty years, I would argue, precisely the same form of repression has shaped the memory of Japan’s relationship to the Korean War. The vision of ‘procurements’ as an abstract phenomenon boosting Japan’s economic growth has allowed historians and others to see only the lavish generosity of war – the glittering surface of Korean War era Tokyo – while forgetting the dead: the whispering corpses beneath who were, in the end, a crucial source of that generosity.

This vision of the war in quantitative economic terms makes invisible not only the millions of victims of the war within Korea, but even the hundreds of people from Japan (both Japanese and ethnic Koreans) who were killed or injured in the war. The quantitative imagery also obscures the terrifying and life-changing experiences of the thousands of Japanese who witnessed the war at first hand. Within the borders of Japan itself, the view of procurements in aggregate terms makes it easy to forget the particular and material ways in which the servicing of war affected Japanese economy and society. So many small scale histories, stories that fail to fit the image of ‘Japan’s Marshall Plan’, remain to be told: stories of the Japanese nurses who tended catastrophic war injuries, of workers who manufactured napalm and other incendiary weapons to be dropped on Korea (and were, in some cases, killed in accidental explosions as a result46), of the women who were procured for ‘rest and recreation’ by US/UN forces in the red light districts of Tokyo, Yokohama, Sasebo, Kokura, Okinawa and elsewhere. ‘Procurements’ were not only a matter of numbers and upward curves on graphs. They also involved lives and bodies.

The Korean War has never really ended. No peace treaty has ever been signed. Korea remains divided. Hardly a day passes without Japanese newspapers reporting on the military threat from North Korea, and hinting at the possibilities of wars to come. In these tense circumstances, the task of re-envisioning Japan’s Korean War is an urgent one. It is time to hear the bodies speak.

——————

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The research on which this article is based was funded by the generosity of the Australian Research Council.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History in the Division of Pacific and Asian History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, and a Japan Focus associate. Her most recent books are Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era and To the Diamond Mountains: A Hundred-Year Journey Through China and Korea.

Recommended Citation: Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Lavish are the Dead: Re-envisioning Japan’s Korean War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 52, No. 3, December 30, 2013.

Related articles

•Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas

•Heonik Kwon, Healing the Wounds of War: New Ancestral Shrines in Korea

•Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War

•Heonik Kwon, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War

•Heonik Kwon, The Ghosts of the American War in Vietnam

NOTES

1 Ōë Kenzaburō (trans. John Nathan), “Lavish Are The Dead”, Japan Quarterly, vo. 12, no 2, April-June 1965, pp. 193-211.

2 Ōë, “Lavish Are The Dead”, pp. 199-200.

3 Chalmers Johnson, Conspiracy at Matsukawa, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1973, p. 23; see also William S. Borden, The Pacific Alliance: United States Foreign Economic Policy and Japanese Trade Recovery, 1947-1955, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1984, p. 146; William J. Williams, A Revolutionary War: Korea and the Transformation of the Postwar World, Chicago, Imprint Publications, 1993, p. 209; Mark Metzler, “The Occupation”, in William Tsutsui ed., A Companion of Japanese History, Oxford, Blackwell, 2009, pp. 264-280, quotation from p. 275; Aaron Forsberg, America and the Japanese Miracle: The Cold War Context of Japan’s Postwar Revival, University of North Carolina Press, 2000, p. 84.

4 For example, John Bowen, The Gift of the Gods: The Impact of the Korean War on Japan, Hampton VA, Old Dominion Graphics Consultants Inc., 1984; Reinhard Drifte, ‘Japan’s Involvement in the Korean War’, in James Cotton and Ian Neary eds., The Korean War in History, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1989, pp. 121-134; Michael Schaller, ‘The Korean War: The Economic and Strategic Impact on Japan‘, in William Stueck ed., The Korean War in World History, Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 2004, pp. 145-176.

5 Christina Klein, Cold War, Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2003.

6 “Shitai arai no arubaito”, entry in the Japanese version of Wikipedia, accessed 2 January 2013.

7 Nishimura Yoichi, Hōigaku kyōshitsu to no wakare, Tokyo, Asahi Bunko, 1995, pp. 46 and 50.

8 Jan Harold Brunvand, The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends and their Meaning, New York, W.W. Norton, 2003.

9 Bradley Lynn Coleman states that the American Graves Registration Service, which returned US remains via morgues in Kokura and later also Yokohama, recovered the remains of 36,576 US servicemen killed in Korea. Bradley Lynn Coleman, ‘Recovering the Korean War Dead, 1950-1958: Graves Registration, Forensic Anthropology, and Wartime Memorialization’, The Journal of Military History, vol. 72 no. 1, 2008, pp. 179-222, reference to p. 217.

10 Furue later migrated to Hawaii, where he became a renowned forensic anthropologist, but his limited academic credentials were to become a source of controversy: it seems that he never completed graduate study at the University of Tokyo. See Thomas M. Hawley, The Remains of War: Bodies, Politics, and the Search for American Soldiers Unaccounted For in Southeast Asia, Duke University Press, 2005, pp. 106-108.

11 Hanihara Kazurō, Hone o yomu:Aru jinruigakusha no taiken, Tokyo, Chūkō Shinsho, 1965, ch. 1; see also ‘Chōsen sensō shitai shorihan: Aru jinruigakusha no kaisō’, in Tōkyō 12-Chaneru Hōdōbu ed, Shōgen: Watashi no Shōwashi, vol 6, Gagugei Shorin, 1969, pp. 164-177.

12 Hanihara, Hone o yomu, quotation from p. 10.

13 John D. Martz Jr. ‘Homeward Bound‘, Quartermaster Review, May-June 1954, accessed 8 January 2013.

14 Nam G. Kim, From Enemies to Allies: The Impact of the Korean War on US-Japan Relations, San Francisco, International Scholars Publications, 1997, p. 154.

15 ‘Home from Battle’, Pacific Stars and Stripes Far East Weekly Review, 18 November 1950.

16 See telegram from US Embassy Manila, 11 February 1958, re Embassy tel 2918 (Tokyo 86), in Okinawa Prefectural Archives, microfilm of National Archives and Records Administration documents, Records of the US Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands, box 6 of HCRI-LA, folder no. 2, ‘Foreign National – Filipino’; on the Vinnell Corporation, see for example telegram from CG RYCOM Okinawa to CINCFE Tokyo, 29 November 1950, in Okinawa Prefectural Archives, microfilm of National Archives and Records Administration documents, ‘RYCOM Nov. 1950’.

17 Kawamura Kiichirō, Nihonjin senin ga mita Chōsen Sensō, Tokyo, Asahi Communications, 2007, p. 22.

18 On Japanese sailors and labourers in the Korean War zone, see Ishimaru, ‘Chōsen Sensō to Nihon no kakawari’. On the Red Cross nurses, see Kokkai Gijiroku, Sangiin, (record of the proceedings of the Upper House of the Japanese Parliament) 25 January 1953. On Japanese base workers at the Korean War front see Tessa Morris-Suzuki, ‘Postwar Warriors: Japanese Combatants in the Korean War‘, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 10, Issue 31, No. 1, July 30, 2012.

19 Roy E. Appleman, South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1987, p. 386.

20 For example, Fangong yishi fendou shi, bianzhuan weiyuanhui ed., Fangong yishi fendou shi, Taipei, Fangong Yishi Fendou Shi Jiuye Fudaochu, 1955, refers to an instance of an important Chinese POW being transferred to Tokyo, where he was questioned by an official of the GuoMindang. I am grateful to Dr. Cathy Churchman for providing me with this information.

21 For further discussion, see Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, chs. 3 and 4.

22 ‘Chōsen sensen ni tobu Nihonjin no chi: Sude ni nanasenninbun okuru’ Asahi Shinbun (evening edition), 16 January 1953, p. 3.

23 John C. Cook, ‘Graves Registration in the Korean Conflict‘, The Quartermaster Review, March-April 1953 , accessed 4 January 2013.

24 Coleman, ‘Recovering the Korean War Dead’, p. 192.

25 Cook, ‘Graves Registration in the Korean Conflict’.

26 Cook, ‘Graves Registration in the Korean Conflict’.

27 Hanihara, Hone o yomu, p. 67.

28 Hanihara, Hone o yomu, p. 83.

29 Hanihara, Hone o yomu, pp. 87-95.

30 Hanihara, Hone o yomu, pp. 131-138.

31 Hanihara, Hone o yomu, pp. 167-168.

32 Hanihara, Hone o yomu, pp. 44-45 and 168.

33 Yasuzo Ishimaru, ‘The Korean War and Japanese Ports: Support for the UN Forces and its Influences, NIDS Security Reports, no. 8, December 2007, pp. 55-70, quotation from pp. 63-64.

34 Interview with Hamada, in ‘Chōsen sensō shitai shorihan’, pp. 174-75; on the riot and its background, see also William T. Bowers, William M. Hammond and George L. McGarrigle, Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea, Washington DC, United States Army Center of Military History, 1996, pp. 79-81.

35 Quoted in Bowers, Hammond and McGarrigle, Black Soldier, White Army, p. 65

36 Bowers, Hammond and McGarrigle, Black Soldier, White Army, p. 79.

37 On the results of the enquiry, see Bowers, Hammond and McGarrigle, Black Soldier, White Army, p 80. Other than their book, I have found no work in English on the Korean War that mentions the Kokura Riot. Very few Japanese language histories of the Korean War era mention it either, though it does provide the setting for Matsumoto Seichō’s novel, Kuroji no e, which was published by Shinchōsha in 1965.

38 Bowers, Hammond and McGarrigle, Black Soldier, White Army, p. 159.

39 Hanson W. Baldwin, ‘Tense Lands in China’s Shadow’, in Lloyd C. Gardner ed., The Korean War, New York, Quadrangle Books, 1972, pp. 128-138, quotation from p. 131. (Baldwin’s essay was originally published in the New York Times Magazine on 24 December 1950).

40 Werner Bischof, Japan, London, Sylvan Press, 1954. The heavily orientalist tone of the text, composed by Robert Guillain after Bischof’s untimely death in 1954, fails to obscure the power of the photographs.

41 Ishimaru, ‘The Korean War and Japanese Ports’, p. 63; on Korean War conflicts over access to ports, see also Nakamoto Teruo, Sasebo-kō sengoshi, Sasebo, Geibundō, 1985, p. 165.

42 See, for example, Nakamoto, Sasebo-kō sengoshi, p. 148.

43 Ono Toshihiko, ‘Kita-Kyūshū Mojikō no kōwan rōdōsha to sono Chōsen Sensō taiken’, Shakai Bunseki, no. 32, 2005, pp. 133-149, citation from p. 137.

44 Ono, ‘Kita-Kyūshū Mojikō no kōwan rōdōsha’, pp. 140-141; for further details of acts of sabotage during the Korean War, see Nishimura, Ōsaka de tatakatta Chōsen Sensō, ch. 6.

45 Ono, ‘Kita-Kyūshū Mojikō no kōwan rōdōsha’, pp. 143-144.

46 To give just one example, three major explosions, one in January 1952, one in August 1952 and one in June 1953, destroyed sections of Nihon Yushi’s Taketomi factory, killing two workers and seriously injuring four others. The Jan. 1952 and June 1953 accidents are reported in Nihon Yushi KK ed., Nihon Yushi Sanjūnenshi, Tokyo, Nihon Yushi KK, 1967, pp. 554-555; the Aug. 1952 explosion is reported in the Asahi Shinbun evening edition, 19 August 1952, p. 3.