The Idea, and the Obstacles

President Xi Jinping’s call for a “new type of great-power relationship” in meetings in 2013 with President Obama raises important questions about the future of US-China relations. On the surface, it appeared that the two leaders were on the same page. At the June summit, Obama agreed with Xi that “working together cooperatively” and bringing US-China relations “to a new level” were sound ideas.1 When the G-20 countries convened at St. Petersburg in September, Obama said of Xi’s proposed new model: “we agreed to continue to build a new model of great power relations based on practical cooperation and constructively managing our differences.” But he added that “significant differences and sources of tension” remain with China, implying that China’s “playing a stable and prosperous and peaceful role” in world affairsremained a matter of US concern.2

|

Xi Jinping with Obama, February 15, 2012 |

Obama thus endorsed a “new type” of relationship in theory but seemed to want practical results before actually embracing it. Exactly why a new type of relations remains elusive, despite the multitude of contacts and interdependencies between China and the United States, and despite the fact that most Chinese and American analysts believe in the central importance of their relations, comes down to mistrust.3 And beneath the mistrust lie sharp differences in global perspective that stem from the two countries’ different self-perceptions and status in the international order.

But first: What do China’s leaders mean by a “new type of great-power relationship” with the United States? One prominent Chinese observer, Zhang Tuosheng, has written that a key characteristic should be that it “break[s] the historical cycle in which the rise and fall of great powers inevitably leads to antagonism and war,” instead relying on “equality and mutual benefit, and active cooperation.”4 “Equality and mutual benefit” was one of the five principles of peaceful coexistence, a mainstay of China’s foreign policy since the establishment of the People’s Republic. Its significance today is that the Chinese are not content to be a junior partner of the United States; they believe they have arrived as a great power and want to be treated accordingly. They don’t want “G-2”-co-dominion with the United States over world affairs. But the Chinese do demand consultation and coordination: C-2, as the former Chinese state councilor, Dai Bingguo, put it.

There are a least five obstacles to C-2. One is differing notions of international responsibility. In 2005 Robert Zoellick, then a deputy secretary of state in the George W. Bush administration, proposed that China become a “responsible stakeholder” (fuzeren de liyi xiangguanzhe) in the international system. Zoellick hoped to attract Chinese leaders with the idea that the United States valued China as a partner in international affairs. But the reception was lukewarm, as a number of Chinese analysts decided that what Zoellick really meant by “responsible stakeholder” was that China should support the US position on key international issues such as North Korea’s nuclear weapons, Iran’s nuclear plans, and global finance. US policymakers today still use that expression when trying to push China in the US direction, as when Obama remarked at St. Petersburg that China’s rise must be peaceful.

Chinese leaders and foreign-policy specialists prefer to refer to their country as a “responsible great power.” They say that their “peaceful development” policy will break the pattern of rising powers challenging the dominant power for top position. They ask how the United States can speak of global responsibility in light of its unilateral interventions in the Middle East and Central Asia, its hard line on negotiating with North Korea and (until recently) Iran, its failure to put its financial house in order, and (in response to US accusations of computer hacking) spying on China and many others. The Americans ask how China can speak of being a “responsible great power” when it acts aggressively in support of its territorial interests in the South China Sea and Sea of Japan, and when it rejects strong sanctions to deal with North Korea’s and Iran’s nuclear-weapon ambitions. On many other international issues, such as global warming and energy, the two countries similarly have widely divergent ideas about what responsibility means. Unless and until the United States and China reach agreement on what it means to be a globally responsible great power, it is hard to imagine that a “new type” of US-China relationship can evolve.

|

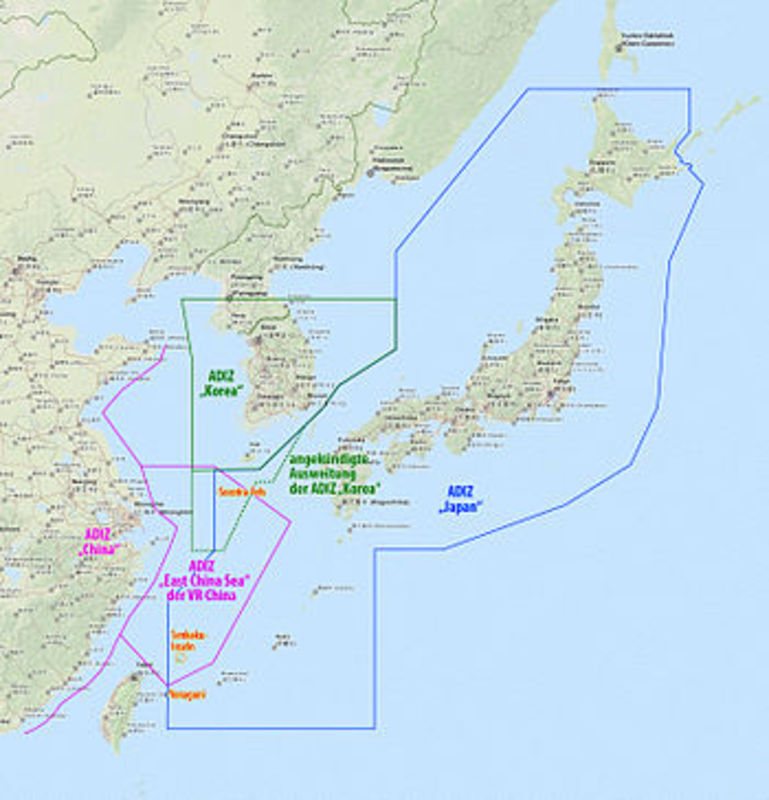

Chinese and Japanese Air Defense Zones |

A second major stumbling block to creating a “new type of great-power relationship,” and perhaps the most important one, is the different self-conceptions of China and the United States. As a rapidly rising power and a “big country,” China not only expects to be consulted on all major international questions. It also expects to have a major, if not preeminent, role in its relations with neighboring countries. “China does not intend to challenge [the United States] as its power grows, but rather seeks to increase its influence within the system,” one prominent Chinese analyst has written. It wants to reform the system, not subvert it.5 While accepting that the United States is a Pacific power, Chinese authorities now resist the notion that the United States has some special claim to predominance in Asia and the western Pacific. More to the point, they see the United States as the chief obstacle to China’s rise-and as taking actions aimed at “complicating its security environment.”6

The United States, on the other hand, claims exceptional status in the international community. Its leaders see the country as having universal values everyone should want and, as head of the “Free World,” being custodian of freedom and democracy. Unlike China, the United States believes it has the right and responsibility to speak its mind about every country’s internal political affairs. Whereas Chinese leaders give priority to rapid development and preserving internal order, US leaders focus on remaining “number one” in world affairs and maintaining the capability to deploy military power all over the globe. US leaders voice suspicion about China’s international ambitions and demand greater transparency on China’s military spending and weapons programs. And while applauding China’s rapid economic growth, US political and some business leaders argue (as they did over the trade gap with Japan in the 1980s) that it is often based on unfair government policies.

Cold War Politics

A third obstacle is the legacy of the Cold War. Chinese analysts frequently refer to US “cold-war thinking” as a basic hindrance to better relations. Zhang Tuosheng, like many other Chinese analysts, points out that the idea of a new relationship emerged out of a good deal of rethinking among Chinese specialists about the post-Cold War order-the new “international pattern” (guoji geju). He observes that the Chinese no longer accept a one-superpower world, even though accepting that the United States is still the most powerful country. They emphasize the multipolar, multidimensional character of the contemporary era and seek a “harmonious world,” which requires a “win-win” perspective above all in defining the China-US relationship.

But neither side can claim to have overcome Cold War thinking. Cyber war and computer hacking, Taiwan’s status, naval confrontations, and territorial disputes have all been handled much as they were during the Cold War-with self-justifications, accusations, and occasional shows of force rather than serious negotiations or recourse to international adjudication. The Sino-Japanese dispute over China’s proclaimed air defense zone, which overlaps with Japan’s ADZ, is a case in point. Many Chinese analyses refer to realist power transition theory to express concern about a confrontation between a rising power and a dominant power. US officials such as Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton have also referenced that theory. Yet neither country has suggested creating a high-level body, above the level of bilateral dialogue groups, that might adopt new rules of conflict prevention in an effort to avoid a Cold War-style confrontation.

Actually, the United States and China should have reason for some optimism in this regard, given the ninety or so official bilateral (Track I) forums at which they regularly meet, their extensive commercial and financial ties, and their numerous people-to-people and NGO contacts. But finding common ground remains elusive in large part because the ideological dimension of US-China relations contains important Cold War elements. The US side does not accept parity with China any more than it accepted parity with the Soviet Union. Nor are US leaders strong believers in a multipolar world. Meantime, in China, Mao-era notions of “struggle against (US) imperialism and hegemonism” survive.7

Fourth, there remain a number of problematic communication issues between the two countries. Defining international “responsibility” has already been mentioned. “Containment,” “hegemony,” “cooperation,” and “consultation” are fraught with political ambiguity. Chinese notions of sovereignty, particularly on the high seas, are challenged by US notions of “freedom of the seas.” Protection of human rights means very different things to Beijing and Washington, as does freedom of the press. Media reports of the other’s politics and foreign policy views are often distorted. Journalists working in China have to be careful about what they say if they want a visa for their next visit,8 just as Chinese news outlets and journalists have to weigh conformity with the unwritten rules of criticism or face silencing by the great Chinese firewall. Confucius Institutes in the United States, part of Chinese efforts to enhance their soft power, have sometimes been attacked by US academics as propaganda platforms.9

The fifth obstacle in US-China relations is the military imbalance. Although some US analysts see China as catching up with the United States in military capability, the fact is that by nearly every indicator of military power, the United States has a huge lead over China. Whether we are talking about military spending (several times China’s), nuclear and conventional weapons, air and naval capability and technology, allies and overseas bases, or deployments (actual and potential), there is simply no comparing the two countries. And while it might be said that China’s substantial year-to-year increases in military spending will eventually yield a military equal or superior to that of the United States, such a prediction neglects two facts: the United States will not be standing still while China modernizes its military, regardless of US budget woes; and Chinese leaders are determined not to follow the Soviet Union’s destructive path of trying to match US military budgeting or weapons. China has demonstrated that it is a formidable regional military power, particularly when it comes to contingencies that involve Taiwan and Japan. But when its leaders protest US containment of China, they are acknowledging that China once again is ringed by a huge array of US firepower and basing options that put it at a great strategic disadvantage in the event of an armed conflict with the US and its allies.

Thus, talk of a “new type of great-power relationship” is premature. As far as I know, Xi Jinping’s idea has not generated serious official interest in the US government. US policy toward China remains a combination of competition, cooperation, and containment (or constrainment), unchanged from previous recent US administrations and more laden with mistrust than before. For US leaders to accept President Xi’s invitation would mean (in their view) conceding comparable status and influence to China-a remarkable concession, one that would be politically very risky. These days, no US political leader would contemplate sharing leadership with China, since that would be tantamount to acknowledging that the era of US leadership in Asia, the Pacific, and worldwide was over. Chinese analysts surely understand that, for they know that no Chinese leader could survive if he argued that China should abide by US notions of “responsible stakeholder.” Nationalism, in a word, is alive and well in both countries.

Seeking Common Ground10

Nevertheless, President Xi’s idea may start a useful dialogue with the United States and others about alternatives to a world dominated by a single hegemon. As the United States faces numerous domestic problems, starting with an increasingly dysfunctional political system and seemingly endless military involvements in the Middle East and Central Asia, it may have to give serious thought to the idea of a strategic partnership with China on issues of vital mutual importance. Contrary to the view of some political scientists, the world does not have to rely on a hegemonic power to operate peacefully and productively. Leadership can, and should, be a shared responsibility. So far as Asia is concerned, that means a US-China relationship that is cooperative and mutually respectful-C-2, in short. The benefits of US-China cooperation should be self-evident-for example, in the demilitarization and exploration of space, international financial stability, environmental protection, peacekeeping missions, humanitarian assistance, and prevention of cyberattacks.

US cooperation with China will not be possible on all issues, and may even be undesirable in a few instances. The “war on terror” was an example of misplaced and exaggerated common interest that lent justification to China’s crackdown on ethnic “separatists.” A common policy on murderous dictatorships will always be very difficult to craft, as Syria most recently demonstrates. But as we witness more frequent national and regional crises that have global implications and major human consequences-the Chernobyl nuclear plant meltdown of 1986, the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998, Southeast Asia’s tsunami in 2008, the US financial crisis of 2008-2010, Japan’s nuclear plant disasters of 2011, mass hunger and civil wars in developing countries, and uncontrollable global warming-we come to understand the imperative of a cooperative approach to real security. Asian countries would be among the greatest beneficiaries of a system in which they were not squeezed by two competing giants as happened during the Cold War. And a cooperative US-China relationship would have one more crucial payoff: the opportunity for both countries to shift attention and resources away from each other and into environmental challenges and support for impoverished, crisis-prone areas of the world.

The United States cannot afford to be on a negative trajectory with China, and the reverse is equally if not more true. Seeking (or being reasonably perceived as seeking) to contain China, and pretending that US (or Western) superiority will endure indefinitely, are not sound ideas in a world that is increasingly integrated economically and ecologically, and in which China is playing ever larger geopolitical and economic roles. Nor will worrying about the “China challenge” improve the US economic or political situation-no more than will China’s worrying about “US hegemony” solve China’s internal problems. The United States needs to take care of its own affairs, with a sense of purpose that springs from its professed values and enormous material advantages. Let China’s people and leaders worry about their country’s domestic affairs. They do; and they have plenty to worry about: official corruption, income inequality, an aging population, and serious water, air and other environmental problems, to name just a few.

Toward a Better US-China Relationship

The history of US-China relations shows that when they are positive and win-win, the consequences for regional security in Northeast Asia are likewise positive. When, on the other hand, those relations are marked by tension and competitive tit-for-tat actions, regional security in Northeast Asia suffers. Take the matter of security and stability on the Korean peninsula. A cooperative US-China relationship, marked by regular military and civilian engagement, can go a long way toward promoting improved inter-Korean communication, laying the basis for productive multiparty dialogue on security issues (whether a resumption of the Six Party Talks or a successor group, as discussed below), and minimizing dangerous miscalculations from occurring in the wake of a sudden crisis such as North Korea’s collapse. The news in late September 2013, following the Obama-Xi meeting at St. Petersburg, that China has compiled a long list of equipment and materials that will not be allowed to be shipped to North Korea because of their potential use in weapons of mass destruction is an example of what can happen when high-level US-China dialogue takes place.

Thus we ask: What steps can be taken by the United States and China to reduce tensions, promote trust, and widen the basis for cooperation?

First, US military planning should change. The budget-driven reductions in US military spending, certain weapons acquisitions, and manpower that began in 2012 will be positive under at least four conditions relevant to Asia and to China in particular. The reductions must be accompanied by a change in US forward-deployment of forces and extended nuclear deterrence. They must eliminate or significantly cut back redundant weapons systems, nuclear as well as conventional. The United States-and Japan-must resist calls for Japan to become a more active security partner in response to China’s rise,11 for as the dispute over air defense zones shows, a US-China clash stemming from US security commitments to Japan is an ever-present possibility. Those force reductions must affect missions too, i.e., elimination of unilateral US interventions to change regimes or build nations. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton set the right tone when she said at a US-China dialogue meeting in 2012 that “no global player can afford to treat geopolitics as a zero-sum game” and that “if China’s rising capabilities means that we have an increasingly able and engaged partner in solving the threats we face to both regional and global security, that is all good.”12

Unfortunately, none of the four conditions seems likely to be met. US military doctrine remains wedded to “full-spectrum capabilities,” “military superiority,” and the ability to defeat “more than one enemy” at a time. The “rebalancing” of US forces to Asia and commitment to an “Air-Sea Battle Plan” explicitly aim at what the Pentagon calls China’s “anti-access, area-denial” strategy aimed at Taiwan.13 In my view, it is hard to see how new US force deployments will benefit the long-term interests of the ROK, Australia, Japan, or ASEAN in maintaining positive relations with China. To the contrary, as two former Australian prime ministers have argued, the Obama administration’s emphasis on military strength in Asia needlessly risks alienating Beijing and does not serve their country’s interests.14 Moreover, the policy undercuts professed US hopes for gaining China’s cooperation on international issues and establishing strategic stability in relations with it.

China, on the other hand, has also taken actions that reduce confidence in its proclamations of a “harmonious world” and a “peaceful rise.” Its naval support of claims to Diaoyudao and Xisha in the Spratlys seeks to defend sovereignty, but it alienates neighboring countries and risks open conflict, particularly with Japan. China’s assertiveness also invites precisely the response it wants to avoid, namely, an increased US military commitment to Asian allies-the Philippines and Japan in particular. Active patrolling of disputed waters also raises questions of trust in Southeast Asia inasmuch as China has supported codes of conduct that promise nonuse of force.

The continuing emphasis by both China and the United States on military power in support of diplomacy suggests the need to go beyond bilateral forums when seeking to build confidence. Regular Track I and Track II dialogues involving the ROK, Japan, and other interested parties should take place under joint China-US chairmanship. Direct, regular channels of communication between top-level officials below the presidents need to be established, especially between military leaders.15 Communication in crisis situations has long been a problem in US-PRC relations, and although we are far from the Korean and Vietnam war eras when opportunities for direct dialogue were largely absent, incidents such as the US bombing of China’s embassy in Belgrade in 1999 and the forced landing in Hainan of a US EP-3 military surveillance aircraft in 2001 show how weak effective lines of communication remain.16

Second, China and the United States should lead the way toward creating a new security dialogue mechanism (SDM) for Northeast Asia.17 Formats such as the Six Party Talks on North Korea’s nuclear weapons, writes one Chinese specialist, might “gradually become a more regular and systematic mechanism” for regional security.18 I suggest that we not wait for another round of the Six Party Talks before moving ahead, since those talks may never succeed in reaching agreement that would actually eliminate North Korea’s nuclear weapons. Beijing and Washington might do better to focus on the SDM idea, since that would create a permanent institution devoted to many other regional security issues, including environmental and territorial disputes-issues that are more amenable to resolution than denuclearization, and might produce enough trust to eventually reach a verifiable agreement on it. The SDM would have the authority to convene on the call of any member. It would be “an early warning and crisis management system,” as the Chinese specialist said. His comment suggests a larger point: as China becomes increasingly comfortable working within multilateral groups, US diplomacy with China might profit from doing the same in order to arrive at a common position on regional security issues.

Third, a US-PRC code of conduct that prevents the kinds of dangerous confrontations that have occurred at sea and in the air, most recently the December 2013 near-collision between US and PRC ships, would be enormously beneficial. Reducing and redeploying US forces involved in close surveillance of the China coast around Hainan would be an essential element of any such negotiation. The good news here is that direct China-US military dialogue has a history. But that dialogue has been irregular, subject to disruption whenever US-China disputes become ugly. It remains to be seen whether or not “rules of the road” can be agreed upon to prevent serious disputes.

Conclusion

People often ask whether or not this century will belong to China or the United States. This is really the wrong question. The right one is, How could world leaders go about creating a legitimate and effective framework for cooperative security, one that lays the groundwork for addressing the most serious human security problems? For the United States, China, and the other countries with regional and global reach, the answer must include practicing new forms of leadership, deepening cooperation with each other, and embracing common security as the touchstone of national security. They must recognize that the greatest security challenges of our time are poverty-and violence in response to poverty-and destruction of the environment, and that these challenges can only be effectively met by making them a common priority. Military buildups and resort to force or threat are irrelevant to such problems, or may exacerbate them; indeed, they are the primary contributors to mistrust and miscalculations. If China and the United States can find common ground on cooperative security, both can truly lay claim to being responsible great powers.

Recommended citation: Mel Gurtov, “The Uncertain Future of a ‘New Type’ of US-China Relationship,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 52, No.1, December 30, 2013,

Mel Gurtov is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University, and Editor-in-Chief of Asian Perspective. His most recent book is Will This Be China’s Century? A Skeptic’s View (Lynne Rienner, 2013).

Notes

1 See their press conference remarks of June 8, 2013.

2 “Remarks by President Obama and President Xi of the People’s Republic of China Before Bilateral Meeting,” September 6, 2013.

3 “Strategic distrust” (zhanlue huyi) is also the chief finding of a unique joint study by two senior US and Chinese analysts. See Kenneth Lieberthal and Wang Jisi, “Addressing U.S.-China Strategic Distrust,” Brookings Institution, John L. Thornton China Center Report No. 4 (March, 2012). See also David Shambaugh, ed., Tangled Titans: The United States and China (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013).

4 Zhang Tuosheng, “Ruhe goujian Zhong-Mei xin xing daguo guanxi” (How to Construct a New China-US Great Power Relationship), Nautilus Institute Special Report, July 23, 2013, at www.nautilus.org.

5 Wu Xinbo, “Chinese Visions of the Future of U.S.-China Relations,” in Shambaugh, ed., Tangled Titans, p. 377.

6 Wu, p. 376. Dai Bingguo is quoted by Wu (p. 376) as saying, with obvious reference to the United States: “We hope that what they say and do at our gate or in this region where the Chinese people have lived for thousands of years is also well intentioned and transparent.” See also Wang Jisi’s section on Chinese perceptions in the aforementioned study with Kenneth Lieberthal.

7 Zhang Tuosheng (“Ruhe goujian Zhong-Mei xin xing daguo guanxi“) acknowledges the obstacle posed by Cold War thinking on both sides, particularly their military establishments, as exemplified by worst-case scenarios (zui huai qianjing). But he insists that such thinking poses a more serious problem in the US.

8 The New York Times reported that a PRC government spokesman, Hong Lei, said: “As for foreign correspondents’ living and working environments in China, I think as long as you hold an objective and impartial attitude, you will arrive at the right conclusion”-a statement right out of 1984. Mark Landler and David E. Sanger, “China Pressures U.S. Journalists, Prompting Warning from Biden,” New York Times, December 4, 2013, online ed.

9 Marshall Sahlins, “China U.,” The Nation, November 18, 2013.

10 This section draws upon the final chapter of my book, Will This Be China’s Century? A Skeptic’s View (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2013).

11 For example, Richard L. Armitage and Joseph S. Nye, “The U.S.-Japan Alliance: Anchoring Stability in Asia,” report of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, DC, August 2012.

12 “Remarks at U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue Opening Session,” Beijing, May 3, 2012.

13 See Michael O’Hanlon and James Steinberg, “Going Beyond Air-Sea Battle,” Washington Post, August 23, 2012.

14 Both former prime ministers argued for US emphasis on a cooperative relationship with China. See Malcolm Fraser, “Obama’s China Card?” Project-Syndicate, July 11, 2012; and Paul Keating, cited by Greg Earl, “US Wrong on China: Keating,” The Australian Financial Review, August 6, 2012.

15 See Michael D. Swaine, “Conclusion: Implications, Questions, and Recommendations,” in Swaine and Zhang Tuosheng, eds., Managing Sino-American Crises: Case Studies and Analysis (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2006), p. 425.

16 See analyses of those cases in Swaine and Zhang.

17 See my “Averting War in Northeast Asia: A Proposal,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 9, No. 2 (January 10, 2011).

18 Wang Yizhou, “China’s Path,” p. 16.