Nihonkoku Kenpo Kaisei Soan (Proposal for Amendment of the Constitution of Japan)

Central Office for the Promotion of Constitutional Reform: Drafting Committee

The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan

27 April, 2012

Nihonkoku Kenpo Kaisei Soan: Q&A (Proposal for Amendment of the Constitution of Japan: Q&A)

Central Office for the Promotion of Constitutional Reform

The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan

October, 2012

There is a rumor in Japan that Aso Taro, former Prime Minister and present Deputy Prime Minister, never reads real books but only cartoon books: manga. It is said that when he was PM he kept a stash of these in the back of his official car so he could read them going to and from meetings and other duties. If these rumors are true, they would go a long way toward explaining his recent gaffe. On 29 July this year, speaking before an ultra-rightist audience on the subject of Constitutional amendment, he said, according to the Asahi Shinbun’s summary,

It should be done quietly. One day everybody woke up and found that the Weimar Constitution had been changed, replaced by the Nazi Constitution. It changed without anyone noticing. Maybe we could learn from that. No hullabaloo.

Aso was bombarded with criticism from within Japan and from around the world, from people shocked to learn that there is a political leader in a major democratic country who could confess to believing that something useful about how to deal with democratic constitutions can be learned from the Nazi example. After a couple of days, he “retracted” the statement. Trouble is, you can’t talk the cat back into the bag once you’ve let it out. And also, if you make a statement that reveals your dreadful ignorance (The Weimar Constitution was never amended by the Nazis; the Nazis did not take over the government “quietly”) retracting it will not persuade people that you weren’t so ignorant after all.

|

Aso Taro |

Aso’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has long wanted to get rid of Japan’s highly democratic and war-renouncing Constitution. In fact, revising the Constitution is included in the Party’s founding principles, adopted in 1955 and pursued thereafter. Partly, and most famously, they want to restore to the government the right to make war, which the present Constitution took away from it. But also, they believe that the present Constitution destroyed public discipline by granting the people too many rights. They have an intense nostalgia for the pre-war days when the people were subjects and not citizens, and pretty much did what they were told. So logically it shouldn’t be so surprising that this romanticization of the good old Axis days would generate warm feelings toward their old Nazi partner.

In order to sustain this nostalgia for the old days, the LDP finds it necessary to rewrite the story of the old days, to make it appear as an appropriate object

While the LDP has made some gains in revising the textbooks, so far they have been unable to persuade a sufficient number of the Japanese people that changing the Constitution is a good idea, nor have they been able to muster the 2/3 majority needed to get a Constitutional amendment through the National Diet. This year’s overwhelming election victories placed Abe Shinzo, one of the strongest advocates of constitutional amendment, in the seat of power. The Party is now in a position to make a serious attempt.

This does not mean that the LDP is aiming for a Nazi-type regime. They have their own, local, model for authoritarian government: the Japanese government as it was before 1945. It also doesn’t mean that they expect to reestablish that system just as it was. They are politicians who claim to be

On April 27 2012,, the LDP published a new Proposal for Amendment of the Japanese Constitution. Both Aso and Prime Minister Abe Shinzo were Senior Advisors to the constitutional drafting committee. So far as I know, this document has not been translated into English. As many critics have pointed out, the word “amendment” in the title is inappropriate, as the constitution depicted in it is utterly different, in letter and in spirit, from the present Constitution. As is well known, both the Italian and the German post-war Constitutions contain clauses prohibiting amendments that would move their governments back in the direction of Fascism or Nazism. The post-war Japanese Constitution contains no such specific provisions, though there are general clauses that some people interpret as meaning that. In any case, if either the Italian or the German government adopted a policy of returning to its pre-war political system, that would hardly be considered a purely internal affair. Similarly, the world ought to know that Japan’s LDP, as Aso’s slip illustrates and the LDP’s Proposal spells out in detail, is planning just such a transformation. But before discussing that Proposal, I need to say a few words about the nature of the Constitution Japan has now.

The Forced Constitution

The LDP argues that as the Constitution of Japan was forced on the country by the US Occupation after World War II, Japan has every right to amend or replace it. Its political ideals are those of American Democracy, its vocabulary is not derived from the vernacular, its writing is

Japanese supporters of the Constitution try to refute this by showing that the Constitution, both at the time of its adoption and in the decades since then, has had overwhelming support from the people. This is important, but if you conclude, “Therefore the Constitution was not forced”, you miss something. The fact that the Constitution has been supported by the people does not mean that it was not forced; rather it changes the picture of who forced what on whom.

Just about allgood constitutions are acts of force. A good constitution is designed to place limits on the powers of government, to replace absolutism with rule of law, and in many instances, with democratic processes. It is very rare for rulers, be they kings or oligarchs, voluntarily to place such limits on themselves, or to accept such limits, unless they are forced to. This has been true since King John, presumably with trembling hand, signed the Magna Charta.

The U.S. Occupation troops and the Japanese public disagreed on many things in 1945, but they agreed – though for different reasons – on one: the government and the military of Imperial Japan had way too much power. The Constitution was designed to reduce that power. In this it is a remarkable document: the first 40 clauses are almost entirely aimed at reducing government power – a long list of things the government may not do. The Constitution placed the Emperor within the framework of the law; it replaced Imperial sovereignty with popular sovereignty; it changed human rights clauses from favors granted conditionally by the Emperor to inalienable rights; it transformed a people who had constitutionally been defined as “subjects” (臣民)into rights-bearing citizens, laying the groundwork for the very active grass-roots political action of the post-war period; it took away from the government the right of belligerency – the right to make war.

Of course, the people who were holding power under the existing system on the whole (with some notable exceptions) hated all this, and tried to resist and sabotage it in every way they could. So when they say it was forced on them, that accurately describes their experience. But it was not forced on “Japan” by “America”; rather it was forced on the Japanese ruling class by an alliance that existed very briefly in 1945, between the Occupation and the Japanese public. Moreover, aside from whether MacArthur and his advisors’ motivations were good, bad or indifferent – whether they were acting as New Dealers, conquerors or (as is more likely) a mishmash of the two – the power that was taken from the Japanese political class was not carried back to Washington DC, but transferred to the Japanese people.

|

MacArthur and the Emperor |

The historical period in which this was possible was brief: by the end of 1946 the Cold War was beginning, and the Occupation had launched what is widely known as the Reverse Course, which in general meant a shift from democratization of a former enemy to mobilization of an anti-Soviet ally. By this time many in the Occupation and in the U.S. government regretted the Japanese Constitution, especially its Article 9, but it was too late. The instrument by which the U.S. Government did succeed in transferring a piece of Japanese sovereignty to the U.S. was not the Constitution, but the Japan-U.S. Mutual Security Treaty, forced on Japan as a condition for signing the Peace Treaty in 1952, which in effect gives the U.S. Government control over the main lines of Japanese foreign policy. As for the Constitution, its enforcer, from 1946 to the present, the power that has stymied the efforts of the conservative political class to amend it, has been the Japanese people (though the Government has succeeded in greatly weakening it through what is called “amendment by interpretation”. I shall return to that point below).1

The LDP Proposal: The Preamble

Preambles to constitutions are typically written in a particular form. They are not assertions of fact, nor are they predictions of things to come. Rather, they bring facts into being. They take the form that language philosopher John Austin called “performative utterances”.2 Examples of performative utterances are, when your boss says “You’re fired” (at which point you are out of a job); when the priest says “I now pronounce you man and wife” (from which point you and the other are married); when the administrator of the driver’s examination says “You pass” (from which point you may, if you also pay the fee, legally drive an automobile); or when the jury says “guilty” (at which point you are officially a criminal). In each case the declaration needs to be made by a person or persons with the authority to make it.

Constitutional preambles are written in this form, as declarations. The one making the declaration is not the person or committee who actually wrote the draft; rather it is the person or persons understood to have the authority to make such a declaration: the sovereign.

The Preamble to The Constitution of the Empire of Greater Japan (aka The Meiji Constitution, 1889) follows this form. The first word in it is Chin (朕), a Japanese word for “I”, which only the Emperor can use, and which is translated into English as the royal “We”. The Meiji Emperor, of course, did not write this Constitution, but it was he who enacted it; in effect, it was his command to the people. In the English translation the operative words are “We . . . hereby promulgate . . . .”

|

Promulgation of the Meiji Constitution |

The present Constitution follows the same format, stood on its head. The first words in its Preamble are “The Japanese people”; the operative verbs are “proclaim” and “establish”. Thus popular sovereignty is not simply announced as a principle; “the people” are placed in the role of the enactor of the Constitution, replacing the Emperor. And most significantly, just as under the Meiji Constitution the Emperor was understood to be outside the law (the commander does not command himself), so the present Constitution contains no clause stipulating that the people have an obligation to obey it.3

Whereas both the Meiji and the present Constitutions are clear in their theory of sovereignty, the LDP Proposal reduces it to a muddle. The first word in its Preamble is “The Japanese State”:

The Japanese State, having a long history and a unique culture, privileged to be headed by the Emperor who symbolizes the unity of the people, is ruled under the principle of the sovereignty of the people, with division of powers into legislative, executive and judicial.

In this odd collection of allegations, the important things are, 1) either the drafters of this Proposal don’t know much about writing constitutions, or else they are deliberately trying to muddle the question of sovereignty; 2) “The Japanese State”, while not qualified to play the role of sovereign, is announced as the main character in this constitutional Proposal; 3) the Emperor, not mentioned in the Preamble to the present Constitution, is brought in as a large, though vague, presence; 4) the assertion of popular sovereignty, coming directly after this, is unpersuasive.

The vagary lies in the expression that I rendered as “privileged to be headed by”, which is the single untranslatable Japanese word

In trying to determine whether itadaku is related to power, the Kojien Japanese dictionary’s definition is not much help, giving only a few synonyms – respect words meaning “to receive”.. One of the synonyms however is houtai (奉戴). If you look x this up in the Kojien it gives you itadakimatsuru (戴き奉る)、that is, the same two characters in reverse order, meaning, again, “to respectfully receive”; this too is not much help. Sometimes when I am searching for the nuance of an obscure word in Japanese, I find that the Japanese-English dictionary is helpful. When the word doesn’t exist in English, the lexicographer works hard to get it across by giving multiple examples of usage. Thus, in the Kenkyusha Japanese-English Dictionary, for houtai an example given is “to have (a prince as a president)”. Interestingly, the same example appears in the Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary. If “prince” means here a royal head of state, and “president” means chief executive of a government, and if itadaku is its synonym, then the use of that word in the Preamble would strongly imply that political power and authority are to be returned to the emperor. But we must be careful: an example of usage is not a definition, and the part in parentheses was made up by the lexicographer. All we can say is that were a royal head of state to take over as chief executive of the government, in such a case itatadaku or houtai would be the proper word in Japanese to use.

In order to emphasize its character as a performative utterance, I quoted only the subject and verbs in the first sentence of the present Constitution, but it contains much more.

We, the Japanese people, acting through our duly elected representatives in the National Diet, determined that we shall secure for ourselves and our posterity the fruits of peaceful cooperation with all nations and the blessings of liberty throughout this land, and resolved that never again shall we be visited with the horrors of war through the action of government, do proclaim that sovereign power resides with the people and do firmly establish this Constitution.

In the Proposal, this is replaced, in its second sentence, by,

Our country, despite the desolation and multiple catastrophes of the Second World War, has survived and developed, and now plays an important role in international society and, under the principle of pacifism, promotes friendly relations with all countries, contributing to the peace and prosperity of the world.

Once again, instead of the Japanese people acting, determining, resolving, proclaiming and establishing, we have a set of (highly debatable) assertions about the Japanese state, this time identified as “our country” (我が国). But as the words “the Japanese people” do not appear in this sentence, it isn’t clear who the “our” refers to. As the LDP often behaves as though Japan were its private property, one wonders whether by “our country” they mean their country.

Another big change is that, while the present Preamble sees the government as to blame for the war, the Proposal depicts “our country” as the victim and heroic survivor of that war. As for “the principle of pacifism”, what is meant by that will become clearer when we get to Article 9.

The third sentence in the Proposal’s Preamble reads,

The Japanese people will defend their state and homeland with pride and self-respect, and while respecting basic human rights, revere harmony [wa(和)], and in the spirit of mutual aid both within the family and in society as a whole, build up the state.

Finally “the Japanese people” are given the status of the subject of a sentence, but not necessarily that of its narrator. The sentence is not performative but a set of allegations about “the Japanese people”, not as “we” but as “they”. And as the allegations are largely counterfactual (depending on the person you are looking at), what the sentence really amounts to is a list of duties – in effect, a set of commands to the people. Who, then, is this commander?

Moreover, the sentence (and for that matter the Proposal as a whole) reverses the present Constitution’s understanding of means and ends. Instead of government being the means to achieve a free, peaceful, orderly and prosperous life for the people, the people are seen as a means to build up the government – more accurately, the state. The fourth sentence continues in this vein.

We, respecting both freedom and discipline, while protecting our beautiful land and natural environment, will promote education and scientific technology, and through energetic economic activity, develop the country.

Again, a list of duties. For the first time “We” becomes the subject of a sentence, but still it gives an image of the Japanese public as the LDP would wish them to be. One suspects the “We” is there to put it in a form that can easily be recited in chorus in the schools. The final sentence in the Preface reads,

The Japanese people, in order to pass on our wonderful traditions and our state in perpetuity to our descendents, do hereby establish this Constitution.

Finally we come to a proper performative sentence, allegedly spoken by “the people” and ending with “establish” (制定). But what came before that (and what comes after) does not fit that form and violates constitutional logic. The Preamble is made up of words of praise for the state and lists of duties for the people, but it makes no sense for the sovereign to prescribe duties and deliver commands to itself. Behind this puppet “the people” there has to be someone else. But who that is, is not made clear.

The Emperor

Article 1 of the present Constitution reduces the Emperor from Sovereign to “the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people”. This by no means abolishes the Emperor System, either in the government structure or in the minds of the people, but it radically reduces it from what it was. In the Proposal’s Article 1, the Emperor is declared to be head of state(元首).

As a political term, “head of state” is a wide basket holding a variety of types ranging from absolute dictators to royal figures who are allowed no political power or authority, but serve only in ceremonial roles. Under the present Constitution, the Emperor of Japan is supposed to be in the latter category. Thus in the LDP-published pamphlet Proposal for Amendment of the Japanese Constitution – Q&A it is explained that in calling the Emperor “head of state” nothing is changed; only the actual situation is properly named. This might be persuasive if there were no other changes in the articles pertaining to the Emperor. Trouble is, there are. In the present Constitution, Article 3 reads,

The advice and approval of the Cabinet shall be required for all acts of the Emperor in matters of state . . . .

In the Proposal, the word “approval” has been deleted.

In the present Constitution, Article 4 states,

The Emperor shall perform only such acts in matters of state as are provided for in this Constitution and he shall not have powers related to government.

In the Proposal, the word “only” has been deleted.

In the present Constitution, Article 7 gives a list of the ceremonial duties the Emperor may perform, prefaced with the following words:

The Emperor, with the advice and approval of the Cabinet, shall perform the following acts in matters of state on behalf of the people.

In the Proposal’s revised version, both “advice” and “approval” have been deleted.

The text of the present Constitution’s Article 3 is relocated to come at the end of this

In addition to what is stipulated in [the list] above, the Emperor shall engage in public activities such as ceremonies sponsored by the state, local governments, public organizations or the like.

This clause contains two subtle escape phrases, which I have rendered “such as” and “or the like”(In Japanese both are その他). One must read carefully to avoid missing them. But they open two doors to the Emperor which are locked down in the present Constitution. How large those doors are, and what might go through them, are impossible to know at this stage.

There are several more additions to the chapter on the Emperor. One gives constitutional authority to the Emperor-based calendar system, which at present is not much used outside government and right-wing organizations (according to it we are presently in the year Heisei 24). Another is to make the sun flag(日章旗) and the song kimi ga yo (君が代)into the constitutionally authorized national flag and national anthem. Both of these are controversial, carrying as they do memories of the era of militarism and abject Emperor worship. There are still people who refuse to sing the song or bow to the flag. Thus the Proposal adds another clause:

The Japanese people must respect the national flag and the national anthem.

Yet another command to the people, telling them what emotion it is their duty to feel. Today, at some public schools in Japan, during matriculation and graduation ceremonies the school Principal or members of the Board of Education will walk among the faculty and look at their mouths to confirm whether they are actually singing the anthem. If this provision becomes law, will we be seeing them walking also among the attending parents to check their loyalty to the State?

Article 9: The Peace Clause

In the present Constitution, Article 9 stipulates,

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes.

In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Some pacifists get quite romantic about this, a few even campaigning to have the Article awarded the Nobel Peace Prize or given World Heritage status. The reality, however, is not quite that splendid. E. M. Forster famously wrote that democracy may be worthy of two cheers but certainly not three; I would say that at this point in history, Article 9 deserves maybe one.

Regarding the text of the Article itself, as a teacher of political theory, I find it quite wonderful. On the one hand, it is written in language as clear as clear gets. On the other hand, many people find it incomprehensible. It flies in the face of the common sense of international relations, and it violates the very definition of the state as given us by Max Weber: the social organization that claims a monopoly of legitimate violence. Well, no, the Japanese Constitution does not renounce the violence of police power or judicial power (the death penalty is still in effect), but still many people will ask, If the state doesn’t have the power to make war, then what on Earth is it? Article 9 is so radically in violation of political “common sense” that there are people, including (perhaps especially) scholars of constitutional law, who can read it over and over and fail to make out what it says. There are actually people drawing salaries and status from major universities who seriously claim that its true meaning is that the Japanese government ought not to spend more than 1% of its budget on military defense (search through Article 9 to your heart’s content, you will not find “1%” mentioned anywhere). There are people who argue that the condition “as a means of settling international disputes” means that war may be used for purposes other than that. And there are people who argue that no matter what is written in it, the state possesses the right of belligerency as a natural right. This reasoning perfectly violates the central principle of the Constitution, which is that the government/state possesses the powers that the sovereign people give it, and no other. (It is also strange to argue that an artificial organization could have a natural right.) All of these interpretations share what might be called the method of deductive reading: it would make no sense for this Article to mean what it says; therefore it doesn’t. And they are examples of the “amendment by interpretation” process that I mentioned above.

But while the language of Article 9 is clear, the role it has played in Japanese politics is ambiguous. As it – together with the Preamble – was written, it depicts a policy of national defense founded on peace diplomacy. Just as Switzerland has been spared invasion not because of the fearsomeness of its military (with all due respect) but because of its usefulness to all sides as a place where cease-fires and peace treaties can be negotiated, so Japan, on the basis of this Constitution, could have become respected as a different sort of peace force. Unfortunately, neither the government nor the public ever quite got up the gumption to attempt this experiment, with the result that Japan, as a party to the Japan-US Security Treaty, is under the US “nuclear umbrella”, hosts a large number of U.S. Military bases (mostly in the colony of Okinawa) and has built up a highly trained and elaborately equipped Self-Defense Force (SDF). The Japanese Self-Defense Force is surely one of the most bizarre uniformed organizations ever there was. They have tanks, artillery, fighter airplanes, warships, rockets, and the training to use them all, but they do not have the right of belligerency. The right of belligerency, put bluntly, is the right of states, invested in their soldiers, that enables those soldiers to kill people in war without being prosecuted for murder.

In each of the various laws that have been passed by the Diet to permit the SDF to operate abroad (whether supporting peacekeeping operations or backing up US military adventures) there appears a clause titled, “Use of Weapons”. And in these there always appears the stipulation that weapons may be used against people only in cases that would fall under the purview of Articles 36 or 37 of Japan’s Criminal Code. These are the articles that permit the use of force in the case of personal self-defense or emergency rescue; rights, in other words, that every civilian in Japan has. With no legal basis but the right of individual self-defense, you cannot carry out military action. Article 36 allows you to use force if your life is in immediate danger and you can save yourself in no other way; in war you may shoot an enemy who, far from threatening you, is unaware of your presence (if you are a sniper, for example, or if you are part of an ambush, or in an artillery unit), and if you have attacked and broken an enemy line, you can shoot an enemy who is running away. Thus nothing is more dangerous than to send the SDF, who do not have that right, into a warzone, as they look like soldiers, act like soldiers, dress like soldiers and are equipped like soldiers, and perhaps even imagine they are soldiers, but have no more right under Japanese law to carry out a military action than a party of duck hunters.

The first time the SDF were dispatched abroad was in support of the U.N. Peacekeeping Operation in Cambodia, in 1992. In 1995 the Commander of that operation, an Australian general, participated in a symposium in Tokyo, which I attended. During a coffee break I asked him how it was to have under his command a party of uniformed men (I think they were all men) who didn’t have the right of belligerency. He looked around to see who was listening, lowered his voice, moved a little closer and said, “I had to wrap them in cotton wool!” A person standing nearby asked, “Weren’t they sent home early?” “No,” he said, “They were sent home according to plan.” Then a smile flitted across his face, and he lowered his voice again, saying, “Of course, you have to understand that when I was deciding the order in which to send back the units, the Japanese unit was not one of the ones I wanted to keep to the end.” The SDF were in Cambodia for political reasons, made no contribution to actual peacekeeping, which sometimes requires military action, and were in fact a major headache for the commanders (they were used for road construction, but we hear that the roads they built washed out fairly soon).

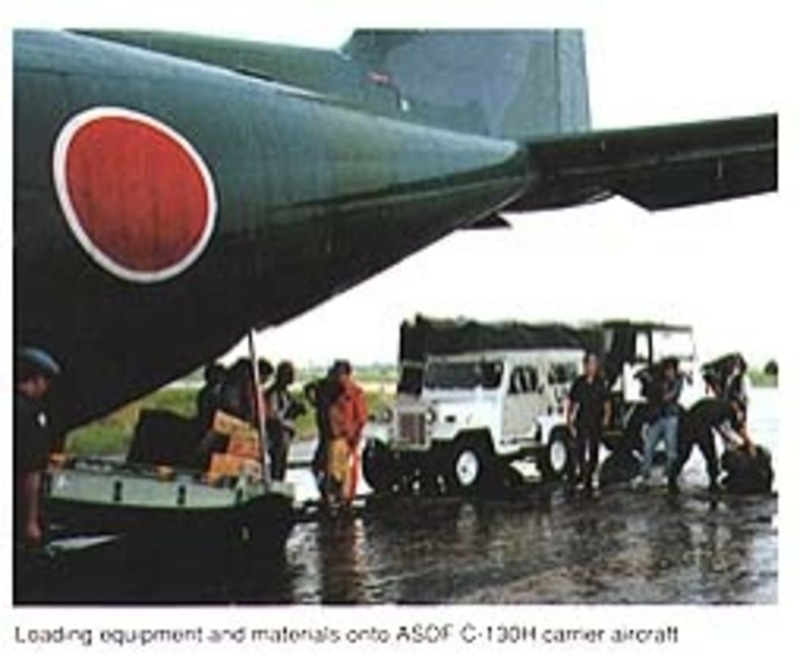

|

SDF in Cambodia |

There is more than one way to look at this. On the one hand, from the standpoint of common-sense international relations, the solution would be to get rid of Article 9 and make Japan’s SDF into a regular military organization with the right of belligerency. On the other hand there is a small but articulate movement in Japan (small now, but big in 1960 and for many years after) that campaigns for the full implementation of Article 9 as written, which would include reorganizing the SDF as a rescue corps (I have been participating in this movement in various ways since 1969). Polls indicate, however, that a slight majority of the Japanese public wants to keep Article 9 as is. “As is” means, with all its contradictions and self-deceptions: Article 9 + US Bases + SDF. Before dismissing this as dishonest, remember that while Article 9 has never been put into practice as written, Japan’s Peace Constitution has served an important function in the real world of politics: in the almost 70 years since it was enacted, no human being has been killed under the right of belligerency of the Japanese state. Considering Japan’s activities before 1945, that is an achievement.

In the Proposal’s revised Article 9 the first paragraph is, somewhat amazingly, almost unchanged. They have changed a couple of words and fiddled with the order of the clauses, but basically it says the same thing. Given that the following paragraphs are intended to found a full-fledged military, one wonders what this first paragraph is doing here (It is immediately followed by the newly added qualifier, “Nothing in the above paragraph should be construed as interfering with the right of self-defense”.) The argument given in the Q&A is a marvel of sophistry. The activity called “war”, they say, has from long ago been prohibited all over the world by international law.

Nineteenth Century style war, beginning with declarations of war, had already been generally understood to be illegal under international law . . . .[presumably the “already” means before 1945 when Article 9 was written.]

It’s true that since the UN Charter was adopted countries don’t declare war

. . . what Article 9 paragraph 1 actually prohibits is limited to the use of military action “as a means of settling international disputes”. . . Therefore, what Article 9 paragraph 1 prohibits are “war” and military action for the purpose of aggression only . . . while military action for self-defense or for international sanctions . . . are not prohibited.

It would be one thing to look at Article 9 and declare that this is what it ought to say; it is quite another to look at it and declare that this is what it does say. As to how they manage the leap from “a means of settling international disputes” to “aggression” I have not a clue. It seems to me that the people fighting the defensive war are also trying to settle an international dispute by kicking the aggressor out. But I suppose that’s old-fashioned: since the adoption of the UN Charter all sides in all wars have claimed to be fighting defensively, so according to this LDP logic, since 1945 there haven’t been any wars at all. It is in the context of this way of thinking that the LDP is able, in the Preamble, to call its Constitutional Proposal “pacifist”.

Of course, not everyone who believes in the necessity of military force uses logic as nutty as this. There are plenty of perfectly reasonable and level-headed people who agree that the condition of peace is far preferable to the condition of war, but believe that having a strong military is the best way to achieve it. In this view, the great purpose of the military is to protect the peace and safety of ordinary people. Trouble is, you search Japanese history (and not only Japanese history) in vain for an era when something like that actually happened. The period when Japan’s military was the strongest in all its history corresponds exactly to the period when by far the largest number of ordinary people died violent deaths. Or if you move to the pre-modern period, you will still be hard-pressed to find an era when the armed class protected (rather than exploited) the farmers, fishers, and craft workers. So there is a kind of romantic wishful thinking at work here: while neither the armed classes nor the state ever behaved that way in the past, surely they will in the future. Well, good luck.

Those who believe the LDP means to establish a new kind of military aimed at protecting the lives of the people might begin by looking at the name the Party has chosen for it. What is now called by the rather vague title, Self-Defense Force (vague because it isn’t clear who the “self” is) are to be called Kokubougun(国防軍), which can be translated National Defense Force or Country Defense Force. One’s memory runs back to the 1930s and early ‘40s when millions of Japanese died (and killed) “for the country” (お国のため). Given that history, the new name is ominous. And in the clause by which the new military is to be established, the priority is made clear.

In order to protect the peace and independence of the country, as well as the safety of the country and the people, a National Defense Force shall be established, with the Prime Minister as its supreme commander.

In this

Defense of the country and the people are not, however, the only tasks to be assigned to the National Defense Force. They will also engage in

international cooperation to protect the peace and security of international society.

The term “international society”, when used by the LDP, generally means “the United States, its allies and its empire” (The Japanese Government has supported every U.S. war since Korea.)If this amendment goes through, we can expect to see National Defense Force troops fighting alongside the US military in whatever its next overseas adventure turns out to be.

The Proposal assigns to the National Defense Force one further field of action. They may

act to protect public order, or to protect the lives and freedom of the people.

Protection of the people, while low on the priority list, has already been mentioned; why should it be mentioned again? The Q&A gives an answer. This clause, it says, refers to

preservation of law and order, protection and rescue of citizens, and action in case of natural disaster.

Responding to natural disaster is welcome of course (though one suspects that the fire department would be better at it); what is troubling is “preservation of law and order”.

This phrase means that the National Defense Force will be constitutionally authorized to carry out military operations not only outside the country, but also within it. Actually this should not come as a great surprise: while we tend to think of national militaries as aimed abroad, in fact they are also – in some cases primarily – aimed within. (Think of Mexico for example, or the Philippines, or Indonesia.) A traditional definition of national territory, not so much used any more, is “the territory a government has succeeded in pacifying”. Probably most of the wars going on in the world today are not cross-border, but between governments and their people, or a part of their people. In Japan in the militaristic period, military police (憲兵) were a major actor in the authoritarian regime, and greatly feared. That the National Defense Force is to be given a law-and-order function is, again, ominous.

The last sentence in the present Article 9 reads,

The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Of course, this has been deleted. Deleted without comment. One might have wished that the LDP had replaced it with, “The right of belligerency of the state shall be recognized”, but no, it has disappeared without a trace. In the Q&A there is no Q regarding its demise, so there is no A. This despite the fact that the reassertion of the right of belligerency is the key to the difference between the present and the proposed Article 9. That is, the right of belligerency is the key to war itself. What distinguishes war from other kinds of large-scale killing does not depend on whether there has been a declaration of war or whether the killers are wearing uniforms and insignia, it depends on whether they have persuaded the world that they are fighting

Human Rights

Following Article 9

Article 28: Japanese subjects shall, within limits not prejudicial to peace and order, and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects, enjoy freedom of religious belief.

Article 29: Japanese subjects shall, within the limits of law, enjoy the liberty of speech, writing, publication, public meetings and associations.

You put in the Constitution the provision that freedom of expression is allowed “within the limits of law”, then all you have to do is make a law prohibiting it, and that’s the end of it.

The present Constitution removes these conditions; human rights are referred to as “eternal and inviolate”. Article 12 reads,

The freedoms and rights guaranteed to the people by this Constitution shall be maintained by the constant endeavor of the people, who shall refrain from any abuse of these freedoms and rights and shall always be responsible for utilizing them for the public welfare.

The references to “abuse” and to “public welfare” may sound like conditions, but I think that rather than commands from above they should be understood as promises (a promise is another form of performative utterance). And “public welfare” is a common sense provision, different in tone from expressions like “duties of subjects”. The public welfare, after all, is the welfare of the people. In the human rights clauses themselves, such qualifications do not appear:

Article 19: Freedom of thought and conscience shall not be violated.

Article 21: Freedom of assembly and association as well as speech, press and all others forms of expression are guaranteed.

The LDP Proposal restores some of the Meiji Constitution’s conditions. To Article 12 is added the phrase,

. . . the people . . . must realize that freedom and rights are accompanied by responsibilities and duties, and must never violate public welfare or public order.

And to Article 21, the freedom of expression article, is added the sentence,

Notwithstanding what is written in the above clause, activity aimed at disturbing the public welfare or the public order, or the forming of organizations for that purpose, shall not be permitted.

To add qualifications such as these to the human rights clauses is to transform them from rights possessed by the people into privileges granted provisionally by the state, at the state’s convenience. The Q&A explains as follows.

The stipulation of “public order” was not included for the purpose of suppressing anti-government activities. … It is common sense that when a person asserts human rights, this must not cause an inconvenience to others.

Well, yes, but when Gandhi and the Indian National Congress campaigned for independence, they caused a terrible inconvenience to the British colonists. When Martin Luther King and others carried out non-violent actions to rid the American South of segregation, they greatly upset the lives of many white racists. When women all over the world campaigned – and campaign – for equal rights, for the men who depend on their subservience, “inconvenience” is hardly the word for it. Japan’s great anti-AMPO (Security Treaty) struggle of 1960 blocked a lot of traffic, and was a great inconvenience to the then Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke (the present Prime Minister’s grandfather) as it cost him his job. Campaigns for human rights always disrupt the social order and inconvenience the people who depend on the absence of those rights. To say that human rights campaigns must be carried out without inconveniencing anyone is to prohibit them altogether.

Very important in the dismantling of the semi-mystical Meiji system was the separation of the state from religion. Article 20 guarantees freedom of religion and prohibits the state from engaging in “religious education or any other religious activity.” The Proposal rephrases this section somewhat, and then adds the following:

However, activities that do not exceed the bounds of social ceremonies or customary activities are not prohibited by this provision.

One of the most emotional issues between the LDP and Japanese supporters of the Constitution – as well as between the Japanese Government and China, and between Japan and the two Koreas – is whether it is proper and constitutional for government officials to pray at the highly militaristic Yasukuni Shrine, which memorializes Japanese war dead including some convicted war criminals. Everyone knew that the LDP Proposal to amend the Constitution would include a clause intended to make visits to that shrine (among other things) constitutional. It seems that this is the clause that they expect to do the trick.

State of Emergency

The fragility of the human rights clauses under the Constitutional Proposal is made even clearer in the provisions for a State of Emergency. Articles 98 and 99 stipulate that in the case of a crisis or a natural disaster, the Prime Minister can declare a State of Emergency, which will put the country on a different legal basis. Article 99 stipulates that when a State of Emergency is declared,

The Cabinet will be empowered to enact regulations that have the power of law, and the Prime minister will be empowered to authorize funds and take other necessary actions, as well as to issue orders to the heads of local governments.

Following political theorist Karl Schmitt’s well-known maxim, “Sovereign is he who

decides the exception,” does this mean that the State of Emergency provisions have

identified the Prime Minister as the new sovereign? But no, Schmitt was careful to

point out that “exception” means, not covered by the law, so that if provisions for a state

of emergency are written into the law, shifting into that state is no longer an

“exception”.(4) It would also be a mistake to call this martial law. Martial law refers

to a situation in which the military has taken over the government, and is ruling the

country as though it were a conquered territory. What this amounts to is a civilian

dictatorship by the Prime Minister. It is also stipulated that the State of Emergency can

be ended by a majority vote of the National Diet – though in the context of Japanese

politics, it is difficult to imagine a National Diet mustering the will to do that. What is

especially interesting in these clauses is what they say about human rights:

Article 99, 3: In this case the provisions pertaining to basic human rights such as Article 14 [equality under the law], Article 18 [prohibition of involuntary servitude], Article 19 [freedom of thought and conscience], and Article 21 [freedom of expression and association] must be respected insofar as possible.

“Insofar as possible” (最大限) may sound not so bad, but it depends on the case.

“Insofar as possible” moves an action from the realm of the forbidden to the realm of “it

corpus insofar as possible.” “I will instruct the police not to fire into crowds of people

insofar as possible.” “Insofar as possible” transforms actions such as these from

“impossible” to “possible”. In the present Constitution, both Article 11 and

Article 97 describe the human rights guaranteed in it as “inviolate”. In

the LDP Proposal, they become violable.

Supreme Law

It is in its final paragraphs that the Proposal’s vagaries are – I wouldn’t say made clear

exactly; rather we are enabled to understand what their function is. In the present

Constitution, Article 98 declares the Constitution to be the supreme law of the nation.

Article 99 reads,

The Emperor or the Regent as well as Ministers of State, members of the Diet, judges, and all other public officials have the obligation to respect and uphold this Constitution.

In the LDP Proposal, the Emperor and the Regent have been taken off this list. As I wrote above, under the Meiji Constitution the Emperor, as the sovereign who issued that Constitution as a command, was prior to it and not obligated to obey it. The present Constitution placed the Emperor under the rule of law (not entirely successfully: it is said for example that the Emperor Hirohito even under the new Constitution was not persuaded that the automobile he was riding in was required to stop for red lights). The LDP Proposal, in eliminating the Emperor’s name from Article 99, clearly places the Emperor outside the law. Nothing in the proposed Constitution can be seen as a restriction on his behavior. Does this mean that, under this Constitution, he would be the sovereign? That is still not clear. He is nowhere identified as the narrator, the one issuing the Constitution as his command. It is difficult to imagine the Emperor becoming the actual day-to-day ruler, making political decisions and issuing directives. It is easier to imagine him serving as the semi-mystical figure whose aura lends a vague sense of sacredness to the state/government as a whole. This is the way the Emperor actually functioned under the Meiji Constitution; it was not he himself, but the political class who served under him, who gained real power from the Imperial Mystery.

One more change in these last paragraphs is important. In the present Constitution, “the Japanese people” are not included in the list of those who are obligated to “respect and uphold” the Constitution. To that clause, renumbered Article 102, the Proposal adds the sentence,

All Japanese people must respect this Constitution.

The Emperor is removed from the list, and the people are added to it. To repeat the

point made above, if the people are indeed the sovereign as claimed in the Preamble,

then the Constitution is their command. Having made this command, it would be

absurd for them to end by commanding themselves to obey it. In this sentence, the

people are commanded to respect the new role of the Emperor (whatever that turns out

to be), to respect the national flag and anthem, to respect the new role of the military, to

respect their newly truncated human rights, and to respect the new Constitution which

deprives them of their sovereignty. The question is, who is doing this commanding?

That remains a mystery.

Notes

1 For a more detailed version of this argument, see my “Japan’s Radical Constitution”, in Tsuneoka [Norimoto] Setsuko, C. Douglas Lummis, Tsurumi Shunsuke, Nihonkoku Kenpo wo Yomu, Kashiwa Shobo, 2013 (Original 1993).

2 John L. Austin, How To Do Things with Words, Harvard U. Press, 1962.

3 For Example see Johannes Siemes, Herman Roesler and the Making of the Meiji State, Sophia University and Charles E. Tuttle, 1968.

4 Carl Schmitt, Political Theology, George Schwab tr., MIT Press, 1985. See also Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception, Kevin Attell, tr., U. of Chicago, 2005.

C. Douglas Lummis is a Lecturer at Okinawa International University. He had promised himself to write no more about the Japanese Constitution, but when he read the newest LDP amendment proposal, broke that promise. This essay is abbreviated and somewhat rewritten from the new afterword to his Kenpo

Recommended citation: C. Douglas Lummis,”It Would Make No Sense for Article 9 to Mean What it Says, Therefore It Doesn’t. The Transformation of Japan’s Constitution,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 39, No. 2, September 30, 2013.

Related articles

• Lawrence Repeta, Japan’s Democracy at Risk – The LDP’s Ten Most Dangerous Proposals for Constitutional Change

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, The Re-Branding of Abe Nationalism: Global Perspectives on Japan

• Herbert P. Bix, Japan Under Neonationalist, Neoliberal Rule: Moving Toward an Abyss?

• Gavan McCormack, Abe Days Are Here Again: Japan in the World

• Lawrence Repeta, Mr. Hashimoto Attacks Japan’s Constitution

• Klaus Schlichtmann, Article Nine in Context – Limitations of National Sovereignty and the Abolition of War in Constitutional Law

• Craig Martin, The Case Against “Revising Interpretations” of the Japanese Constitution

• Koseki Shoichi, The Case for Japanese Constitutional Revision Assessed

• John Junkerman, Gavan McCormack, and David McNeill, Japan’s Political and Constitutional Crossroads