“Even now my sad and vexatious feelings have not changed.”

-Father of girl whose killer was hanged in Tokyo on August 3, 2012 (Asahi Shimbun, 8/3/12, evening edition, p.15)

“It violates the fundamental notion that like crimes be punished alike to allow life or death to hinge on the emotional needs of survivors.”

-Former U.S. federal prosecutor Scott Turow (Ultimate Punishment, 2003, p.53)

AUM Puzzles

The murders committed by AUM Shinrikyo guru Asahara Shoko and his henchmen may be the most malevolent crimes in Japanese history. March 20, 1995 was Japan’s 9/11, and but for a little dumb luck—including the failure to puncture all the bags of sarin that were planted in the subway trains—the death toll could have been much higher than 13 and the number of persons injured might have reached five digits instead of the true total of 6300. Asahara and his followers killed at least 16 people in the six years leading up to that awful Monday morning, and because of their proficiency at disposing of dead bodies the real figure could be two or three times higher. This was murder on a scale Japan has seldom seen, and for every person killed or injured by AUM, dozens more were adversely affected, often in life-wrecking ways.

Seventeen years have passed since Asahara was pulled from a cubbyhole in Kamikuishiki where he hid from police while clutching $100,000 in cash, yet many important matters remain poorly understood. NHK television recently broadcast several hours of interesting speculation, but in the end could not answer why the Tokyo gas attack occurred and why Asahara wanted to precipitate Armageddon.1 Another important question has been even more neglected, for mass murder reflects both a willingness to kill and a failure of control. Why, then, did police fail to stop AUM before Japan’s crime of the century occurred, especially given all the evidence cultists left in the wake of their crime wave, including (a) an AUM badge that was dropped by one of the killers in the Yokohama apartment where attorney Sakamoto Tsutsumi and his wife and son were slain in 1989, (b) a sarin gas attack in Nagano prefecture that killed 8 and injured more than 200 some nine months before the subway attack in Tokyo, (c) sarin leaks at the cult’s chemical factory in Kamikuishiki, and (d) a front-page Yomiuri headline on New Year’s Day 1995 describing chemical compounds detected in Kamikuishiki and linking them to the sarin attack in Nagano? Japanese police were once held in high esteem by many observers,2 but the colossal failure of police to protect the public against AUM has led some analysts to conclude that while most individual officers may be honest and dedicated, Japan’s police force is, as an institution, “arrogant, complacent, and incompetent.”3

|

|

Three commissions were created to investigate what went wrong in the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011, and the US federal government created a commission to prepare “a full and complete account of the circumstances surrounding the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001,”4 but no commission has ever been established to examine these and other AUM-related puzzles.5 The result of this failure to look and learn is a level of ignorance that could prove catastrophic when terrorists target Tokyo again.

AUM and Capital Punishment

Including Asahara, 13 members of AUM have had their death sentences finalized and hence could be hanged at any time. In July, former Minister of Justice Ogawa Toshio said that prosecutors had been “creating an environment to execute Asahara” (Asahara shikei shikko no kankyo-zukuri) through strategic leaks to the mass media,6 while the recent arrests of Hirata Makoto, Kikuchi Naoko, and Takahashi Katsuya following a 17-year manhunt create two new possibilities.

First, Takahashi may join Asahara and other AUM disciples on death row. All of the other drivers who transported sarin hitmen to the Tokyo subway in March 1995 have already been condemned to death, and there is little reason to suppose trial by lay judges will result in greater leniency for a man who escaped accountability for 17 years.7 As of this writing (August 2012), prosecutors have obtained a sentence of death 14 of the 17 times they sought it from lay judge panels, a higher “success rate” than prevailed when panels of three professional judges made life-and-death decisions on their own. Some analysts even believe Democratic Party of Japan Minister of Justice Taki Makoto approved the hanging of two murderers in August 2012 partly out of concern for the effects the executions might have on the forthcoming AUM trials.8

Second, the execution of Asahara and other AUM offenders could be postponed for several years while Takahashi’s case makes its way through the courts. Heretofore, waiting before executing has been standard practice for the Ministry of Justice in cases involving co-offenders who could be sent to the gallows.

The arrests of Takahashi, Kikuchi, and Hirata also create an opportunity to consider what would be gained by killing Asahara and other AUM offenders. In the rest of this article I focus especially on what hanging these murderers might do for victims of AUM’s crimes.9 For the dead the answer is nothing at all, but what about their families, friends, and survivors?

In most criminal cases, victims in Japan and the United States did not receive the help and regard they deserve for much of the postwar period. But in recent years the situation has improved in both countries with the passage of laws protecting and promoting victims’ rights and with the movement to center stage of victims and survivors in criminal courts and the media. In Japan, for example, victims now have the right to sit with prosecutors at trial, question witnesses, make sentencing recommendations, and request that the defendant pay financial damages in cases involving death or injury. These reforms have made a difference—sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse—and many observers believe there remains room for further improvement. In particular, Japan’s Constitution lacks a provision explicitly protecting victims’ rights, there continues to be inadequate financial support for some victims and survivors of crime, and there is still insufficient protection of the privacy of victims—especially the victims of sex crime.10

Some of the most important victim-related changes are not narrowly legal but rather are the effects of broad cultural shifts. Most notably, when capital punishment is framed as a matter of satisfying victims and helping them to achieve “closure” (kugiri o tsukeru)—as is often the case in Japan and the United States—one effect is to legitimate a sanction that has become increasingly difficult to justify on other grounds. A panel of American experts recently concluded that there is no evidence that the death penalty deters homicide, and deterrence through the death penalty in terrorism cases appears to be an even greater chimera because terrorists are often willing to die for their cause.11 Similarly, pro-death penalty claims that the public supports capital punishment or that individual states are sovereign to choose their own punishment policies sound increasingly hollow when confronted with the reality that the death penalty is frequently regarded as a violation of the human right to life.12

In this context, where deterrence is a hollow hope and the abolition of capital punishment is a leading indicator of whether a state is “civilized,” it is no coincidence that the rise of rhetoric about the need to “serve victims” has corresponded with death penalty increases in Japan and the United States, the only two developed democracies that continue to carry out executions on a regular basis. In the United States, “closure” as a concept made its first appearance in the media in 1989, and executions increased six-fold in the decade that followed, from 16 in 1989 to 98 in 1999. Subsequently, concerns about human rights, miscarriages of justice, and the financial costs of capital punishment stimulated greater caution about state killing and large death penalty declines in the 2000s. (In 2011, 13 American states carried out 43 executions while 37 states and the federal government did not execute.) In Japan, too, the number of District Court death sentences almost tripled as victims became more central in media accounts and the criminal process, from an average of 4.5 per year for 1988-1997 to 12.4 per year for 1998-2007. Similarly, a recent report by Japan’s Legal Research and Training Institute found that the proportion of murderers sentenced to death rose almost fourfold after the Tokyo gas attack, from 1 in 400 for 1955-94, to 1 in 160 for 1995-2004, to nearly 1 in 100 for 2005-2009.13

Thus, AUM’s terrorism helped fuel a resurgence in Japanese capital punishment in two ways: directly, by contributing 10 percent of the people who reside on the country’s death rows; and indirectly, by intensifying public fear and fury about crime and thereby legitimating an institution that promises to protect the public and express the outrage that victims and citizens feel.

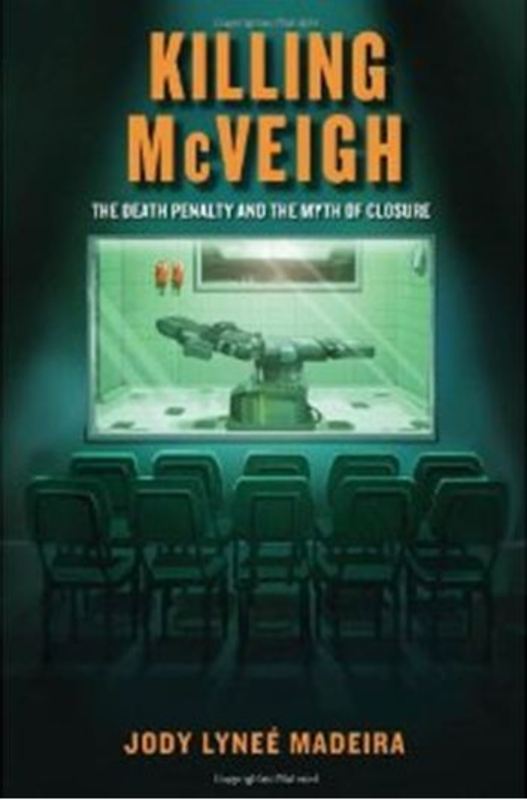

Despite the increased salience of victims and survivors in the capital justice systems of Japan and the United States, there is little solid evidence about how (if at all) the death penalty serves victims. The recent publication of Indiana University Professor of Law Jody Lynee Madeira’s fine book starts to fill this lacuna by providing some answers to this question in the American context.14 Its main conclusion should give pause to people who support capital punishment because “the victims need it.” According to Madeira, many common beliefs about victims and capital punishment are mistaken. Although her book provides evidence about only one case, that case involves the largest terrorist attack ever carried out by domestic offenders on American soil. In this and several other respects, her work has implications for thinking about what killing Asahara might mean for victims and survivors in Japan.

American Terrorists

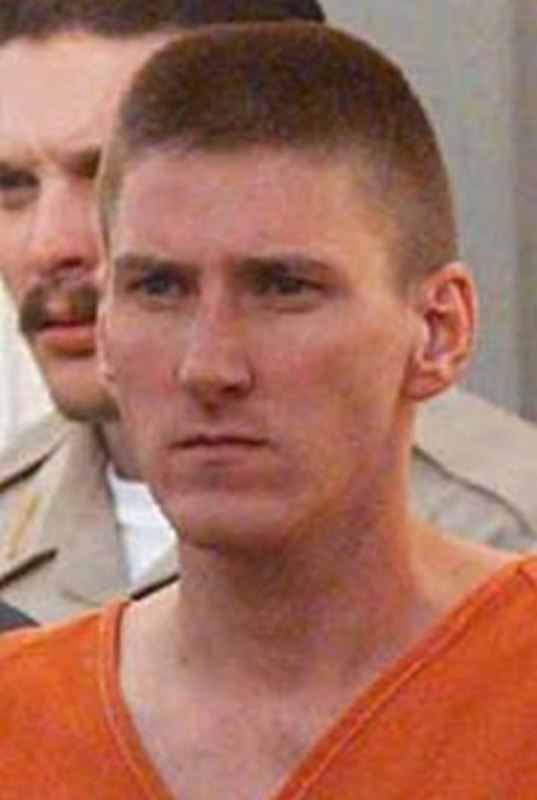

On April 19, 1995—less than one month after AUM attacked the subways in Tokyo—26-year-old Timothy McVeigh set off a truck bomb outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people and injuring 800 more.

At the time, this was the largest act of terrorism in modern American history (the scale of harm would be surpassed when 19 foreign terrorists killed nearly 3000 people on September 11, 2001). Like the Tokyo Gas Attack, this was a direct assault on the central government, and McVeigh chose this target to maximize media coverage. The Murrah Building had an open design that afforded news organizations ample opportunity to obtain photographs and television footage that would convey the full extent of the carnage. In this regard, McVeigh relied on the media to engrave the bombing in America’s collective memory. The media did not disappoint.

There are several other significant parallels between the terrorist attacks in Oklahoma and Tokyo. In both, the principal offender did not act alone: Asahara had a whole cult behind him, while McVeigh had help from Terry Nichols and Michael Fortier. All three of these American terrorists were home grown and highly regarded: they all served in the U.S. military, and McVeigh even received a Bronze Star for his service in the first Gulf War. Similarly, in both cases the offenders committed their crimes while aware that they could be sentenced to death for their acts. In both cases, the offenders believed their violence was justified: by the doctrine of “poa” in AUM, which was perverted to mean that murder might serve a victim’s interest by preventing him or her from accumulating bad karma, and by McVeigh’s belief that he was engaged in a righteous “act of war” against the government, which rendered the workers in the Murrah Building “fair targets” and “enemy combatants” because they were members of the government’s “support structure.” In both cases, the offenders hoped their violence would produce revolutionary change. In both cases, the principal offenders received inconsistent sentences: McVeigh was sentenced to death and then executed by lethal injection in 2001, while Fortier was sentenced to 12 years in prison (he served 10.5) and Nichols escaped a death sentence twice, first in a federal trial and then at trial in the state of Oklahoma (he is now serving a life term). There was inconsistency in Japan too: 14 members of AUM have been tried for murder in connection with the subway attack, and only Hayashi Ikuo received a sentence of life imprisonment, which many people regard as inconsistent with the death sentences received by the other 13 killers. (Hayashi dropped sarin on the Chiyoda subway line, killing 2 people and injuring 231.) The Tokyo District Court Judge who originally sentenced Hayashi (Yamamuro Megumi) still harbors doubts about the propriety of his life sentence.15

|

|

But the most striking parallel between these two cases of terrorism is the incalculable harm done to innocent victims. These were attempts to kill randomly and on a grand scale, and in an awful way they succeeded.

Japan has been called “the state that kills in secret” because the secrecy and silence that surround capital punishment are taken to extremes seldom seen in other nations.16 Like everyone else in the country except a handful of officials in the Ministry of Justice, victims and survivors do not know in advance when an execution will occur, and after the fact news reporting tends to be perfunctory, with little effort to communicate what victims and survivors feel. By comparison, executions in America are much more transparent,17 and the execution of Timothy McVeigh opens an especially wide window onto the sensibilities of victims and survivors because his lethal injection was the most widely viewed execution in America in half a century,18 and because Madeira reports what 33 victims and survivors told her during the seven years she spent researching her book. The next section summarizes several recurrent themes.

American Victims

According to Madeira, terrorism is an intensely unwelcome “toxic intrusion” for victims and survivors (p.19). McVeigh, Nichols, and Fortier not only disrupted hundreds of lives, they desecrated the physical and emotional integrity of their victims. Some victims and survivors analogized this intense sense of violation to being raped—with all the feelings of outrage and impurity that rape often entails. Recovering one’s identity and restoring one’s dignity means learning how to manage the unwanted intrusion.

For many victims and survivors, managing this toxic intrusion is a Sisyphean task. Losing a loved one to murder is unlike any other blow in life, because the survivor’s loss is not the result of something as fickle and unfathomable as disease or as random as an earthquake; it is caused by the conscious choice of another human being. The experience of intentional harm is so far from the core assumptions people usually share when they live together that the reality is difficult to accommodate. The victim’s loss is also compounded by a failure of law, for before the criminal process ever begins law has already failed to perform its most important function: the protection of life and limb (Madeira, ch.2).

Madeira shows that victims and survivors vary a lot, and hold diverse opinions about capital punishment and the criminal process (p.118). At McVeigh’s execution, some victims and survivors swore at the condemned or made obscene gestures in his direction (McVeigh could not see them through the one-way mirror at the prison or the camera that enabled people to watch his execution in Oklahoma). Some victims and survivors who watched this execution felt relief afterward, and a few even clapped or sang songs. And some said McVeigh’s execution reduced his control over their emotions, while a few even said it was “therapeutic” in the sense that it brought temporary relief from his toxic presence.

But memories persist even after killers are executed, and Madeira reports that McVeigh’s execution produced little of the “closure” that America’s culture of capital punishment has promised victims and survivors for the past two decades. Indeed, the subtitle of her book captures the punch line of her research. The Death Penalty and the Myth of Closure finds that there is no such thing as closure in the sense of absolute finality (p.41). Survivors never really “get over it,” though some do cope better than others (p.282).19

According to Madeira, different capacities to cope are rooted in different orientations to “memory work,” which is defined as “an interactive process by which individual family members and survivors construct meaningful narratives of the bombing, its impact on their lives, and how they have dealt with, adjusted to, or healed from this event” (p.xxiii). Thus, memory work consists of the emotional, cognitive, and physical labor of crafting, telling, and retelling stories, through relationships with other people and in conversations with the self (as sociologists observe, the self is largely constructed and sustained through “soliloquizing”).20

|

Madeira’s thesis about memory work has at least six corollaries.

- Coping with murder is an ongoing process that never ends because one’s story must be continuously revised in light of new information, experiences, and perceptions (p.38). The never-ending nature of memory work helps explain why survivors’ sentiments often change over time, as appears to be the case with Motomura Hiroshi, the Japanese man in the Hikari case who passionately advocated capital punishment for the killer of his wife and 11-month-old daughter but who took a somewhat softer tack after the killer’s death sentence was finalized.21 “Time has been my most treasured confidant,” he told reporters at a press conference in February 2012. “It allowed me to view the case with level-headedness. I hope we don’t put three lives [of his wife, daughter, and the defendant] to waste, and use this as an opportunity to attain a society in which we wouldn’t have to use the death penalty.”22

- As for Mr. Motomura, so for many of McVeigh’s victims: “Time, measured in years, seemed to be the biggest aid in coping, contextualizing, and compartmentalizing the bombing” (p.44). Forgiveness was also a crucial step forward for some victims (p.192).

- Doing memory work well requires close attachments to other people. As Madeira notes, “much memory work must take place outside of the courtroom,” and human bonds are essential to survivors’ reconstructive efforts (p.182).

- The law alone cannot make victims whole. In the face of the cruelties that humans inflict on each other—with murder the gravest cruelty of all23—a sense of meaning typically comes from outside the law, and so does healing. Law’s most critical failure is its inability to answer the questions victims and survivors find most compelling. In Oklahoma City these were: Why did they commit the bombing? And why did we have to be victimized? According to Madeira, these incessant questions drive some victims “nuts” (p.149), and coming to terms with terrorism means learning there is “no perfect answer” (p.151).

- Anger is a normal victim response to murder, and it frequently defines the victim’s self and world. Moreover, anger can be productive for some victims, as when it helps organize and direct the victim’s attention and energy, often by eliciting a determination to see something positive come from the loss (p.70).

- But anger can also be deeply destructive to victims and survivors. In various ways, Madeira’s interviewees recognized the insight articulated by Buddha some 25 centuries ago: “Holding on to anger is like grasping a hot coal with the intent of throwing it at someone else; you are the one getting burned.”24

Emotions on Trial

It is difficult to determine the proper role of anger and other emotions in a capital trial. On the one hand, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that “it is of vital importance to the defendant and to the community that any decision to impose the death sentence be, and appear to be, based on reason” (Justice John Paul Stevens in Gardner v. Florida, 1977). Indeed, one theme of American capital jurisprudence since the 1970s has been the effort to rationalize the sentencing process by requiring the substitution of rational principles and rule-of-law values for punitive passions and unguided jury discretion. In the words of the Court’s Penry v. Lyons holding of 1989, the capital sentencing decision must be a “reasoned moral choice,” unencumbered by ignorance and emotion.

Yet the same Supreme Court that emphasizes the importance of rational decision-making also permits American prosecutors to present “victim impact” evidence in the penalty phase of capital trials (Payne v. Tennessee, 1991)—though victims generally are not allowed to make specific sentencing requests, as they are permitted to do in Japan. One prominent death penalty scholar believes “it is hard to imagine an opinion that runs more directly contrary to the Court’s rationalizing reforms.”25 And another analyst has concluded that victim impact evidence in American capital trials “prevents the jury from hearing the constitutionally required story of the defendant,” largely because it is easier for jurors to identify with the murdered victim’s “cognitive schema” than with that of the defendant.26

At Timothy McVeigh’s murder trial, Judge Robert Matsch tried to police victims’ expressions of affect, but in the end prosecutors were permitted to call 38 victim impact witnesses, including 26 family members, 3 injured survivors, 8 rescue workers, and a day care center employee. According to Madeira, their testimony was “so heartrending that sentencing proceedings were fraught with emotions” (p.156). To no one’s surprise, McVeigh was sentenced to death in June 1997. He would be executed four years later. His final statement, a handwritten version of British poet William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus”, could not have been more defiant: “My head is bloody, but unbowed…I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.”27

McVeigh’s main co-offender, Terry Nichols, was not sentenced to death, and it is reasonable to wonder why. Many victims and survivors believed Nichols was as morally culpable as McVeigh, yet he escaped a capital sentence not once but twice, first in a federal trial and then at a state trial in Oklahoma. The principal difference between his own two trials and the earlier one of McVeigh lay not in what was new but in what was missing—especially the tears of the victims. The gut-wrenching stories that characterized McVeigh’s trial became so intense that court guards stocked the media listening room with boxes of tissues. In contrast, Nichols’ defense lawyers were determined to limit the types of victim impact statements that would be permissible, and the judges in his trials ultimately “forced the prosecution to tone down the victims’ testimony to a basic recitation of the facts” (p.162). At Nichols’ federal trial, for example, Helena Garrett simply said “yes” when asked whether she got to see her 16-month-old son one last time before his burial; in McVeigh’s trial she had given a heartbreaking account of having to kiss her son’s feet and legs at the funeral home because his head and face were so badly injured (p.163).

Victims and survivors in Japan now have more voice in criminal trials than they did when the first wave of AUM offenders was being tried. In this sense, recent reforms are having an effect. But change is not necessarily progress, and one critical question is how to regard the increased salience of victims in Japanese capital punishment. In making this judgment one needs to consider two truths about the Japanese context. First, victims and survivors tend to take on an almost sacred status in the criminal process, making it virtually impossible to cross-examine them or question their assertions.28 Second, Japanese judges routinely permit victims and survivors to beg for death penalty outcomes, and many bereaved persons are apparently encouraged to beg by family, friends, and prosecutors.29

I have attended three murder trials in Japan in which prosecutors sought a sentence of death. Victims and survivors were permitted to beg for the ultimate sentence in all three.

In the first lay judge trial in which prosecutors sought a sentence of death, Hayashi Koji was sentenced to life imprisonment for killing two women. Near the end of this trial the son of one victim cried intermittently while reading a five-page statement to the court. He called his deceased mother a “supermom” (supa-kachan) who had many friends and loved nature and karaoke, and he said that while the defendant may regret getting caught for the killings, he feels no real remorse. The son also rebuked the defendant for testifying that his youngest victim sometimes talked smack about her colleagues and customers. “Cut the crap!” (fuzakeru na), he raged at the defendant. “She would not do something like that!”30 The son concluded his statement by asserting—three times—that he wanted the defendant sentenced to death and by imploring judges and lay judges to study the photos of his mother’s bloody body during their deliberations.

In the same trial, the sister of one victim also testified. She started by announcing that she “hates” the defendant because his crimes are “so horrible and evil,” and the longer she spoke the more momentum she gained. She wept loudly while reading her statement, and sometimes interjected how “vexed” (kuyashii) she felt by what the defendant had done. She also rebuked the defendant for trying to “trick” the court in his testimony. “You merely said what was convenient for you,” she insisted. “Give us the lives of our loved ones back!” Near the end of her statement she broke into huge, gasping sobs, and when it became apparent she could not continue, her attorney stepped forward to finish reading it.The final words were as follows:

“I went to visit [my sister’s] grave the other day and I told her that the next time I come I will definitely bring news of a death sentence (shikei hanketsu o kanarazu moratte kuru kara ne). My beloved sister is watching this trial, and I really want the court to give us a death sentence. I desire a death sentence. I hope you will do as I request.”

In a murder trial in Chiba that I attended in the summer of 2011, Tateyama Tatsumi (who had a criminal history as long as his black belt for judo) was sentenced to death for killing a young woman and brutally raping, robbing, and assaulting several other victims. In the penultimate trial session, a parade of the woman’s two parents, their attorney, four victims, and two prosecutors—nine persons in all—spent 195 minutes imploring judges and lay judges to condemn the defendant to death. By comparison, the defense’s allotted time for its closing argument was 60 minutes.

Riding the Elephant

One of the hallmarks of Japanese criminal justice is the almost monopolistic control that prosecutors possess over case information. Prosecutors take numerous statements from suspects and witnesses during the pretrial process (and receive many more from the police), but they do not have to disclose all of them to the defense. Because of recent victims’ rights reforms, prosecutors now possess an enormous emotional advantage as well, for the reforms give victims and survivors a much larger role at trial, and because judges routinely allow powerful emotional testimony from victims and survivors that makes it difficult to carry out the kind of “reasoned moral judgment” that is the prerequisite of principled sentencing.

Research shows that the human mind is divided, like a rider on an elephant. The rider is our conscious reasoning—the stream of words and images of which we are fully aware—while the elephant is the other 99 percent of our mental activities—the intuitive and emotional processes that occur outside of awareness but that govern most of our behavior.31 To allow victims and survivors to express their feelings at trial in their full emotional agony is to make the rider’s already difficult job of steering the elephant even more difficult.

In the third murder trial I watched, Ino Kazuo was sentenced to death by the Tokyo District Court for robbing and killing an elderly man who was relaxing in his apartment on the Sunday afternoon in November 2009 when Ino broke in and stabbed him to death. This murder occurred six months after Ino had been released from prison after serving 20 years for killing his wife and 3-year-old daughter in 1988. On the second day of trial, the victim’s son was allowed to testify that he wanted a death sentence even though the defendant was denying all of the charges against him and even though fact-finding had barely started (the son was permitted to make a second demand for a death sentence at the end of the trial). Studies show that allowing victims to demand a death sentence before the facts have been found significantly shapes the fact-finders’ assessment of what the facts are.32 This is one reason why capital trials in America are bifurcated into guilt and sentencing stages, so that the facts can be found before punishment is imposed. Notably, the only Japanese trial so far in which prosecutors sought a sentence of death and a lay judge panel acquitted—the murder trial of Shirahama Masahiro in Kagoshima in 2010—involved a presiding judge (Hirashima Masamichi) who refused to permit survivors of the two murder victims to make explicit sentencing requests; he insisted that their statements be edited before being read in court.33

The Kagoshima case suggests that as in the two murder trials of American terrorist Terry Nichols, reducing the volume of victims’ tears may also make a difference in Japan. More fundamentally, to allow life and death decisions to hinge on the emotional needs of victims and survivors is to violate the basic principle that like crimes be punished alike—as this article’s opening quotation from Scott Turow suggests. It remains to be seen what victims and survivors will be allowed to say in the murder trial of AUM’s Takahashi Katsuya.

Lessons for Japan

American writer James Thurber often exhorted, “Let us not look back in anger or forward in fear but around in awareness.” There is insufficient awareness of the role that victims and survivors play in Japanese criminal trials, and there is insufficient discussion of the role that they should play. I have written this article in the hope that increased awareness of the evidence from America will help generate more discussion about victims and capital punishment in Japan. I conclude with three lessons for Japan.

First, murder is down in Japan, and terrorist attacks ceased after Asahara was arrested, but random killings (musabetsu na satsujin) continue to make Japan’s public anxious and angry. Those public responses may seem inevitable, but they are as much a product of the media penchant for peddling fear and fury—and of political leaders’ priorities—as they are “natural” human reactions. As Mori Tatsuya recently reported, reality is constructed quite differently in Norway, where Anders Behring Breivik killed 77 people in July 2011 before being sentenced to 21 years in prison in August 2012.34

If looking into the mirror of Norway alerts us to the possibility of responding to terrorism in more constructive terms than resentment and vengeance,35 looking into the mirror of America may awaken us to the reality that capital punishment seldom provides closure for victims and survivors. This is the main negative lesson from the execution of Timothy McVeigh. Punishment does not heal victims, and the criminal law cannot make them whole.

The main positive lesson from the Oklahoma case is that memory work can help to heal some victims and survivors, especially when it takes place in the context of close human relationships. In this sense, personal attachments are crucially important. When murder ruins one or some of them, the constructive thing to do (easier said than done!) is to seek meaning in conversation and connection with friends, family, and loved ones. Moreover, in order to be effective, memory work must continue until the end of one’s life. For victims and survivors, memory work becomes one of life’s essential activities, like eating, drinking, and sleeping.

Finally, one would like to believe that memory work and related acts of remembrance make people and their societies more vigilant in their ability to prevent terrorism and other acts of atrocity. But the truth is not so easy. As September 11 illustrated in the United States, “never again” is “a fairy tale” which ought to be taken to heart by people in Japan and other countries.36 Sooner or later Asahara and the other AUM offenders on death row will probably be executed. For Japan’s leaders, especially those in the Ministry of Justice who control the country’s machinery of death, “looking around in awareness” might help produce the realization that the physical demise of these terrorists will provide neither enduring comfort to victims and survivors nor an obstacle to other zealots who believe it is righteous to kill. As Jody Lynee Madeira concludes in her fine book, the myth of closure is a warning about the false comfort of state-killing, and it is also an exhortation to be vigilant about the future.

David T. Johnson is Professor of Sociology at the University of Hawaii; [email protected]. This article is a revised and expanded version of “Asahara o Korosu to iu Koto: Amerikajin Terorisuto no Jiken kara Higaisha to Shikei ni tsuite Kangaeru”, Sekai (October 2012), pp.214-226 (translated by Iwasa Masanori). Johnson is co-author (with Franklin E. Zimring) of The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia (Oxford University Press, 2009), and co-editor of Law & Society Review. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal associate.

Recommended citation:David T. Johnson, “Killing Asahara: What Japan Can Learn About Victims and Capital Punishment from the Execution of an American Terrorist,” The Asia-Pacific Journal,Vol 10, Issue 38, No. 5, September 17, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

•Philip Brasor, Lay Judge System and the Kanae Kijima Trial

•David T. Johnson, War in a Season of Slow Revolution:Defense Lawyers and Lay Judges in Japanese Criminal Justice

•David T. Johnson, Capital Punishment without Capital Trials in Japan’s Lay Judge System

•Lawrence Repeta, Transfer of Power at Japan’s Justice Ministry

•David T. Johnson and Franklin E. Zimring, Death Penalty Lessons from Asia

•Mark Levin and Virginia Tice, Japan’s New Citizen Judges: How Secrecy Imperils Judicial Reform

1 NHK TV, “Mikaiketsu Jiken”, May 26-27, 2012.

2 See, for example, David H. Bayley, Forces of Order: Policing Modern Japan (University of California Press, 1976, 1991), and Walter L. Ames, Police and Community in Japan (University of California Press, 1981). For a portrait of Japanese prosecutors that is also somewhat positive, see David T. Johnson, The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan (Oxford University Press, 2002).

3 Richard Lloyd Parry, “Japan’s Inept Guardians,” New York Times, June 24, 2012. Parry has also written an excellent book about Obara Joji, the killer and serial rapist who operated for years under the noses of the Japanese police (People Who Eat Darkness, Jonathan Cape, 2011).

4 Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (2004).

5 Several other AUM puzzles remain unsolved and underexplored. For example, why did police fail to find the person(s) who tried to assassinate Japan’s top cop (Kunimatsu Takaji) ten days after the assault on the Tokyo subway? Why did prosecutors arrest Asahara’s lead defense lawyer (Yasuda Yoshihiro) during the guru’s criminal trial on a criminal charge so obscure—obstruction of the compulsory seizure of rental income from a corporation Yasuda was advising—that the Tokyo District Court ultimately concluded it was utterly groundless (appellate courts later overruled)? And why do 1500 people (and one of my friends) still revere Asahara and remain committed to his teachings despite all of the evil done in his name?

6 Aoki Osamu (interviewer), “Ogawa Toshio ga Gekihaku: ‘Asahara Shikei’ to ‘Shikiken Hatsudo’”, Shukan Posuto, July 6, 2012, pp.43-45.

7 After Takahashi’s arrest, Takahashi Shizue, who lost her husband in the Tokyo gas attack, lamented “You must have known about our great suffering as victims, yet why did you run around for so long?” Asahi Shimbun, “‘Naze Koko made Tobo’ ‘Shinjitsu Sematte’ Aum Jiken Izoku kara”, June 15, 2012.

8 Inagaki Makoto, “Govt Resumes Executions: Friday’s Executions Show New Minister’s Determination,” Daily Yomiuri, August 4, 2012.

9 As explained later in this article, the question of deterring terrorism through capital punishment is less complicated and less contentious.

10 Matsui Shigenori, “Justice for the Accused or Justice for Victims?: The Protection of Victims’ Rights in Japan,” Asia-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, Vol.13, No.1 (2011), pp.54-95.

11 Daniel S. Nagin and John V. Pepper, editors, Deterrence and the Death Penalty (The National Academies Press, 2012), and Robert A. Pape, Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism (Random House, 2005).

12 Sangmin Bae, When the State No Longer Kills: International Human Rights Norms and Abolition of Capital Punishment (State University of New York Press, 2007); Roger Hood and Carolyn Hoyle, “Abolishing the Death Penalty Worldwide: The Impact of a ‘New Dynamic,’” Crime and Justice (The University of Chicago Press, Vol.38, 2009); and David T. Johnson and Franklin E. Zimring, The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia (Oxford University Press, 2009).

13 Ida Makoto et al, “Saibanin Saiban ni okeru Ryokei Hyogi no Arikata ni tsuite”, Legal Research and Training Institute, Supreme Court of Japan, July 2012. By comparison, in the United States from 1977 to 1999, about 2.2 percent of all known murder offenders were sentenced to death; see John Blume, Theodore Eisenberg, and Martin T. Wells, “Explaining Death Row’s Population and Racial Composition”, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Vol.1, No.1 (March 2004), pp.165-207.

14 Jody Lynee Madeira, Killing McVeigh: The Death Penalty and the Myth of Closure (New York University Press, 2012).

15 Yamamoto Ryosuke, “Judge Who Spared AUM Doctor Still Has Doubts About Verdict,” Asahi Simbun/Asia & Japan Watch, November 17, 2011.

16 David. T. Johnson, “Hisoka ni Hito o Korosu Kokka”, Jiyu to Seigi, Vol.58, No.9 (September 2007): 111-127, and Vol.58, No.10 (October 2007): 91-108 (translated by Kikuta Koichi); and David T. Johnson, “Japan’s Secretive Death Penalty Policy: Contours, Origins, Justifications, and Meanings,” Asia-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, Vol. 7, Issue 2 (Summer 2006), pp.62-124, available here.

17 Fuse Yusuke, Amerika de Shikei o Mita (Gendai Jinbunsha, 2008).

18 Ten seats were allotted for victims and survivors at McVeigh’s federal trial in Denver, and there were seats for 320 more to watch a live broadcast in an Oklahoma City auditorium. At McVeigh’s execution in Indiana, a lottery was used to allocate 7 seats for victims’ family members, 2 seats for survivors with physical injuries, and 1 seat for other survivors; another 300 watched a closed circuit broadcast in Oklahoma.

19 University of Houston Professor of Law David R. Dow puts Madeira’s point more sharply when he says, “After you kill the bad guys, you’re just as angry as you were before, but there ain’t no one left to hate.” Dow is also the litigation director of the Texas Defender Service, a nonprofit legal aid corporation that represents death row inmates. See his The Autobiography of an Execution (Twelve, 2010), p.174.

20 Lonnie Athens, “The Self as Soliloquy,” Sociological Quarterly, Vol.35, No.3 (1994), pp.521-532.

21 Masuda Michiko, Fukuda kun o Koroshite Nani ni Naru: Hikari shi Boshi Satsugai Jiken no Kansei (Inshidentsu, 2009).

22 Mainichi Daily News, “After Death Sentence Confirmed, Bereaved Family of Young Mom and Baby Takes Step Forward,” February 21, 2012.

23 Among developed democracies, the cruelty of murder is unusually common in the United States. For example, the murder rate in New York City has dropped 80 percent since 1990, but as of 2012 it remains approximately 10 times higher than the murder rate in Tokyo. Killing in the United States stands out in two other ways as well, for America is one of the world’s leading executing states (its 43 executions in 2011 ranked fifth in the world, behind China, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Iran), and it is also one of the most active in carrying out the murder that is called (and sometimes celebrated as) war.

24 See, for example, Madeira, pp.192, 237, 282. See also Simran Khurana, “Buddha Quotes.”

25 David Garland, Peculiar Institution: America’s Death Penalty in an Age of Abolition (Belknap Press, 2010), p.279.

26 Diana Minot, “Silenced Stories: How Victim Impact Evidence in Capital Trials Prevents the Jury from Hearing the Constitutionally Required Story of the Defendant,” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Vol. 102, No. 1 (Winter 2012), pp.227-251.

27 For the whole poem see here.

28 David T. Johnson, “Victims and Emotions in Japanese Capital Punishment”, Hogaku Semina, May 2011.

29 David T. Johnson, “Progress and Problems in Japanese Capital Punishment,” in Capital Punishment in Asia: Comparative Perspectives, edited by Roger Hood and Surya Deva (forthcoming, Oxford University Press, 2013).

30 Hayashi’s youngest victim and his main target was a 21-year-old woman whom he had patronized at an “ear-cleaning salon” in Akihabara 154 times in the 14 months before he murdered her. Hayashi felt unrequited love for the woman—or lust, or longing, or something—and he was angry that the management of her shop had forbidden him to visit any more.Hayashi also testified that the woman sometimes spoke critically about some of her customers and clients, and this was one reason the son of his eldest victim rebuked him. For more details on this case, see David T. Johnson, “Capital Punishment without Capital Trials in Japan’s Lay Judge System,” The Asia-Pacific Journal (December 27, 2010).

31 Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (Pantheon Books, 2012), p.xiv. See also Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), and David Eagleman, Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain (Vintage Books, 2011).

32 David T. Johnson, “Capital Punishment without Capital Trials in Japan’s Lay Judge System,” The Asia-Pacific Journal (December 27, 2010).

33 The Kagoshima case is discussed in more detail in Johnson (2010).

34 Mori Tatsuya, “Genbatsu wa Yuko na Keibatsu na no ka: Norway no moto-Hoso ni Kiku”, Sekai, August 2012, pp.176-183.

35 Norway’s different approach to terrorism does not marginalize victims and survivors. Before Breivik’s trial began, “the court named 174 lawyers, paid by the state, to protect the interests of the victims and their families,” and at trial the court heard 77 autopsy reports. After each report, “the audience watched a photo of the victim, most often a teenager, and listened to a one-minute-long biography voicing his or her unfulfilled ambitions and dreams.” For more detail, see Toril Moi and David L. Paletz, “In Norway, a New Model for Justice,” New York Times, August 23, 2012.

36 Madeira, 2012, p.273.