Post-War Warriors: Japanese Combatants in the Korean War

Tessa Morris-Suzuki

In May 1947 Japan, under the influence of its US occupiers, adopted a new constitution which stated, ‘aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.’1 Yet, just two years after this proclamation of lasting peace (and only five years after their defeat in the Asia-Pacific War) thousands of Japanese citizens were once again in a war zone, engaged in combat-related tasks in their newly liberated former colony of Korea; and this engagement was initiated and overseen by the United States, the very country which had ensured the inclusion of the peace clause in the Japanese constitution.

Although there is a growing body of Japanese and English language research on Japan’s engagement in the Korean War, this corner of history remains surprisingly little known and seldom acknowledged. Historians including Bruce Cumings, Reinhardt Drifte, Onuma Hisao and Wada Haruki have drawn attention to the ways in which US strategies enmeshed Japan in the Korean conflict at multiple levels.2 Recent research by Masuda Hajimu has also emphasized the profound impact of the war on Japanese public and political discourse.3 Yet general histories of postwar Japan commonly continue to depict the country as a passive bystander, fortuitously reaping the collateral benefits of the conflict: a ‘gift from the gods’ (in Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru’s memorable phrase) that is portrayed as descending upon the nation without reciprocal suffering or participation in violence.4 The role of Korean War procurements in jump-starting the Japanese economy is repeatedly emphasized; but the fact that these ‘procurements’ included the physical involvement of Japanese in the conflict is much less generally recognized.5 This article aims to reassess the image of Japan as bystander by focusing in particular on the experiences of some 120 Japanese citizens who served in Korea in US uniforms; for although (as we shall see) their stories were only a very small corner of the history of Japan’s Korean War engagement, their experiences shed some particularly interesting light on the nature of the war and on the relationship between occupier and occupied in postwar Northeast Asia.

Invisible Allies

Not long after the end of the allied occupation of Japan in 1952, the Asahi newspaper published an article about a 29-year-old Tokyo man named Hiratsuka Shigeharu, who had died fighting with US forces in the Korean War in September 1950. Hiratsuka, a painter employed at a US military base in Japan, had gone to Korea with US troops from his base following the outbreak of the war on 25 June 1950, and was believed to have been killed in action not far from Seoul. Hiratsuka’s father sought an explanation and compensation from the US occupation forces, but was told that his son had traveled to Korea illegally and without authorization, and had never been an official member of the UN/US forces in Korea. His family was therefore not entitled to any military benefits.6 A follow up article published in the Asahi the next day reported that Yoshiwara Minefumi and two other young men from Oita Prefecture had also disappeared after going to Korea with the American Forces.7

The occupation authorities (Supreme Command Allied Powers, SCAP) were very well aware of the stories of Hiratsuka and Yoshiwara. Towards the end of 1950, a number of reports had appeared in Soviet, Chinese and North Korean newspapers suggesting that Japanese forces were covertly being used in the Korean War. One Pravda article of October 1950 cited a figure of 8000 Japanese engaged in military activities in Korea, while Chinese and North Korean propaganda increasingly warned of revived Japanese militarism in East Asia.8 These warnings had serious implications. In February 1950, the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China had signed a Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance, one of whose clauses stated that either country would come to the other’s aid to protect it from aggression by Japan. China entered the Korean War in October 1950, and public evidence of Japanese involvement in the Korean War would have dangerously raised the risk of full-scale Soviet intervention and a consequent Third World War.9 The South Korean government also expressed predictable reluctance to see a return of the former colonizers to Korean soil.10

Immediately after the outbreak of the Korean War there had in fact been suggestions by some public figures in the US that Japanese should be recruited to fight in Korea. In early August 1950, Democrat Senator Warren Magnuson proposed a senate bill to allow the US military to incorporate Japanese volunteer soldiers into its ranks – at half the rate paid to Americans – and later the same month Democrat Representative W. R. Poage introduced a broader proposal to allow the US military to recruit citizens of any country, including Japan and Germany.11 Amidst fears of catastrophic military escalation and of a South Korean backlash, though, these schemes received short shrift both from General Douglas MacArthur and from Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida, and neither bill was passed. 12 MacArthur’s staff reassured nervous allies that ‘no Japanese were to be employed with the army in Korea’.13 So reports that Japanese were in fact accompanying US military units to Korea, and that some might have died in action, risked (as one army memo put it) causing ‘serious international complications’, and a top secret US military investigation was launched to examine the matter. 14

An inquiry by Colonel L. J. Shurtleff of the First Cavalry Division confirmed the death of Hiratsuka, but was unable to determine the fate of Yoshiwara, who had apparently been killed, wounded or captured near Daejeon on 20 July while working for the US 24th Infantry Division.15 All US divisions in Korea were then ordered to find out whether they had any Japanese nationals in their ranks, and if so to place them in ‘protective custody’ and repatriate them to Japan.16 On their return, the repatriated Japanese were questioned, fingerprinted, offered jobs with the occupation forces on Japanese soil, and firmly instructed never to tell anyone about their experiences in Korea. Declassified US records show that by 12 February 1951 forty-six Japanese citizens who had been attached to US military units in Korea had been sent home, and between mid-February 1951 and the middle of 1952 a further seventy-two were repatriated.17 One of the two Japanese who had been taken prisoner by the North Korean side was also repatriated to Japan at the end of the Korean War (the fate of the other is unclear).18

These 120-odd Japanese in Korea were just the tip of the iceberg; for, despite official rejection of schemes for the recruitment of Japanese, a much larger and highly secret Japanese involvement in the war was continuing with the full knowledge and support of the US military command. The American authorities were alarmed, not so much by the presence of Japanese nationals in Korea itself, but rather by the fact that some were present in uncontrolled contexts where they risked coming into face-to-face contact with the enemy. As long as Japanese could be kept at sea, or could be firmly confined within UN/US bases, the American military was very happy to make use of their much-needed services. Two months before ordering the return of Japanese nationals from Korea, Douglas MacArthur’s UN Command had secretly approved the dispatch of twenty Japanese minesweepers and five support vessels to the Korean War zone to clear naval access to the North Korean coast. The ships were crewed by a contingent of seamen from Japan’s old Imperial Navy who had never been purged but had instead been used by the occupation authorities for minesweeping duties in Japanese waters. It is estimated that about 1,200 Japanese sailors, most of them ex-Imperial Navy men, took part in Korean War minesweeping operations under US direction.19

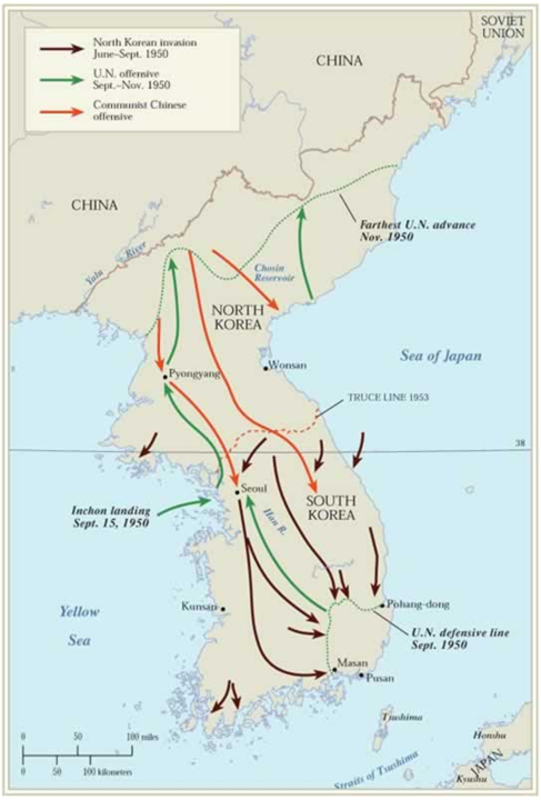

After Japan’s defeat in the Asia-Pacific War, SCAP had also taken over control of the Japanese merchant marine, which was loaned American LSTs (landing ship tanks) to ferry repatriates from the lost empire back to their homelands. When the Korean War broke out, many of these LSTs and other transport ships, together with their Japanese crews, were recruited by the US military to carry forces and supplies into action in Korea. Additional labour to crew landing and transport vessels was recruited via the labour requisition (LR) provisions of Japanese government’s ‘special procurements’ program.20 In a parliamentary committee debate on 7 March 1951, Japan Socialist Party politician Aono Buichi stated that 3,922 Japanese LR workers had manned landing vessels for the Incheon Landing of September 1950.21 The US also borrowed large numbers of ships (with crews) from private Japanese companies for Korean War work including support for the Incheon and Wonsan Landings, engagements which marked crucial turning-points in the war. One of the most prominent of these companies was the shipping firm Tozai Kisen, which concluded an agreement with the US military’s Japan Logistical Command (JLC) to provide 122 small vessels and around 1,300 crew for transport and landing work.22

Meanwhile, Japanese workers were being recruited both via the Japanese government’s official procurements program and through companies like Tozai Kisen to unload supplies, repair equipment and carry out other military support duties for UN/US bases in Korea during the War. These workers were confined either within the bases or on Japanese cargo vessels which had been specially modified for use as floating barracks and were moored in Korean ports. An article published by the Asahi Shimbun in January 1953 reported that there were thought to be about one thousand Japanese labour recruits still engaged in this work in Korea at that time.23 According to an estimate by Japan’s Special Procurement Agency, 56 Japanese sailors and labourers were killed in the Korean War zone in the first six months of the war alone; 23 of the deaths occurred when Japanese-crewed ships were sunk by mines.24 No official estimate of the total number of Japanese killed in the Korean War has ever been published, indeed, there has never been official recognition by the US or Japanese governments of the role of Japanese in the war zone.

‘Houseboys’ in Uniform

In terms both of their numbers and of their military roles, then, the 120 or so Japanese who accompanied US regiments to the Korean War zone were a tiny fraction of Japan’s human commitment to the war. Most described themselves as having worked as ‘houseboys’ (a term then widely applied to adult male servants), cooks, drivers, repair workers or (in a few cases) interpreters. Yet the stories they told to their US military interviewers on their repatriation to Japan provide a vivid insight into the chaos of the Korean War, into concealed aspects of Japan’s war involvement, and into the strange mixture of camaraderie, condescension and exploitation that characterized the relationship between occupier and occupied in postwar Japan. They also speak of the dislocations and blurred identities that lingered as the dismembered Japanese empire was reconstituted into ‘Cold’ War Northeast Asia.

|

|

The testimony itself, of course, needs to be read with caution, for many conflicting interests are at work here. The US military investigators interviewed a number of US employers or coworkers of the Japanese in order to determine who had been responsible for their ‘unauthorized’ arrival in the war zone. Sometimes the testimony of the Americans and Japanese is in conflict; on other occasions, the answers given by three or four repatriated Japanese are so suspiciously similar that they seem rehearsed. The Americans involved were generally eager to avoid being reprimanded for having taken Japanese employees to Korea, while many of the Japanese had an interest in securing a comfortable position as an occupation employee in Japan. Nevertheless, several clear themes emerge from the stories of the repatriates from the Korean front whose stories survive on record.

The great majority had simply followed their US employers onto the transport vessels when American troops were deployed to Korea in the early weeks of the war. Often, neither US employer nor Japanese employee seems to have realized that this might cause problems or evoke an official reprimand. The casual nature of the process is suggested by the testimony of a US army sergeant who helped to arrange the transport of a Japanese mechanic (known to him only as ‘Charley’) to Korea: ‘it was the day we left Camp Drake for Yokohama. I asked [the Major] about Charley going to Korea with us, and he said, OK, go ahead.’25 In some cases, the Japanese employees had specifically asked to be taken to Korea; in others, the initiative had been taken by their American superiors: ‘A Sergeant Smith asked me to come along’;26 ‘1st Sergeant Bush said they would need an interpreter, and asked the Company Commander if I could go, who said it was alright’.27 Almost all the Japanese said that they had gone voluntarily, although one added that, when he agreed to follow his employers to a ‘distant place’, he had not realized that the place in question was Korea.28

In Korea, most of the Japanese continued to occupy the positions that they had held on bases in Japan; but the move to a war zone brought dramatic changes to their lives. For one thing, all now donned military uniforms – in most cases, US uniforms. The exceptions included two Japanese men who chose to join ethnic Korean volunteers receiving training at US bases in Japan, and were incorporated into the South Korean military (a topic to which we shall return). One other Japanese national who traveled to Korea with the US military said that, after his arrival, his American superior had provided him with a Republic of Korea (ROK) military uniform and told him, ‘now you are a Korean’.29 Almost a third of the Japanese employees said that they had been issued with weapons, and even some of those who were unarmed carried out combat-related duties. One unarmed ‘houseboy’ was given the task of carrying mortar ammunition, while another joined his American employer on military patrols until the latter decided that ‘there would be trouble if the Communists found out I am Japanese’.30

The man who was taken along by his company because they needed an interpreter was just one of many who found himself in a very unfamiliar role once he arrived in Korea. After landing in Busan, he traveled with the American troops to Daejeon, where ‘the unit was hit by the enemy and about half were killed or wounded… At eight o’clock at night I lay down in a rice paddy because of the enemy all around… I stayed in the rice paddy all night.’ He then walked for ‘three or four days’, by which time he had lost contact with his unit, with whom he was only reunited several days later. At some point in his journey he was ‘grazed across the face by two burb gun bullets’ and treated on the spot. He told his interviewers that he had been issued with a carbine, and ‘I used it all the time. I don’t know how many North Koreans I killed’.31

Arrival in Korea, indeed, was often just the start of a series of hasty and chaotic movements from place to place as the frontline advanced and retreated: a bewildering and sometimes terrifying experience well illustrated by the account of a young man named Takatsu from Hokkaido, who told his story in fractured but vivid English.32 Like many of the Japanese who went to the Korean front, Takatsu had grown up in circumstances overshadowed by the miseries of the Asia-Pacific War. Both his parents had died when he was a small child, and he had been raised by a foster family before going to work for an itinerant seller of fans. He was still in his teens when he was hired as a kitchen hand at a US military base, where he was given the nickname ‘Benny’. In September 1950, the troops from his base were deployed to Korea, and ‘Benny’ volunteered to join them, having (according to his testimony) been told that if he went to the Korean front he might later be allowed to go to America. A member of the unit gave him a ride to Yokohama in his truck, and Takatsu remained on the truck as it was loaded onto the transport ship, joining the US troops above deck once the ship was en route to Korea.

|

They landed at Incheon, and headed east to Seoul before moving northward as the UN forces in Korea advanced into North Korea towards the Chinese border. The unit to which Takatsu was attached reached the Chosin Reservoir in the far north of Korea, where they came under sustained attack by Chinese forces in one of the fiercest engagements of the war. Takatsu, who had been issued US military fatigues and a carbine, recalled:

the Chinese come and fight maybe every night. Every day and every night about 4 days and many people get killed and shot. We loose most of trucks. Some guys got shot and I helped put them in trucks… The last roadblock, that time, no more officer. I never see officer, just soldier… I stay behind truck. Trucks go out on road and I stay behind trucks. I shoot 4 clips. I keep clips in my pocket. Then my carbine burn up. Many guys get shot.’

Takatsu’s neck was grazed by a bullet and he became dazed and panic stricken, seeing ‘black cones’ dancing before his eyes. He fled though a tunnel into a rice paddy, where he encountered an American and a South Korean soldier, and struggled with them through deep snow to a nearby road: ‘it was just like swimming through snow’. After hours on the road, they eventually met more soldiers and found a local farmer and South Korean military police who were able to guide them to the nearest US encampment. Takatsu, by now in a state of collapse, was treated on the spot before being evacuated to a military hospital in Japan suffering from severe frostbite.

Of the seventy-two Japanese interviewed after their return to Japan, fifteen reported having used their weapons against the enemy, and eight had been wounded; but hardly any received regular pay in Korea, though some were given gifts of money collected from their US comrades-in-arms, or were promised that they would be remunerated on their return to Japan. There are oddly poignant moments in the testimony they gave to their US interviewers: answers given in deferential tones and hesitant English, their clipped phrases merely hinting at life-changing and traumatic experiences, and at the paradoxes of the world in which they found themselves enmeshed. ‘I always treated good by the Americans,’ reads one record of interview, ‘I got no pay. I got food and clothes and cigarettes and candy. I want back to Tokyo to work for Americans again.’33 The testimony of another man named Ito reveals that he had gone to Korea as ‘houseboy’ to an American officer shortly before the outbreak of the Korean War. After the war broke out, the officer had been posted back to the US, but Ito had remained, first working for the American mission in Korea and then for the 21st Infantry Regiment. The interview continues:

Q. Were you issued a weapon?

A. Yes, a gun, ammunition and everything, the same as GIs.

Q. Did you receive any pay while in Korea?

A. No, sir.

Q. Were you ever wounded?

A. Yes, I was wounded once and received the Purple Heart.34

Layered Space and Postcolonial Borders

The ‘unauthorized Japanese’ in Korea had slipped through fissures in the confused and fractured space of Northeast Asia. They lived in a region suddenly permeated by a massive US presence. This presence, though, did not blend into local society, but existed in islands in the midst of Japanese and Korean territory, each island surrounded by its own miniature national borders: Camp Drake, Camp Crawford, Camp Hogan, Camp Bender. Inside these landlocked US islands Japanese employees found an alien cocoon of material abundance amidst postwar poverty, and were quickly incorporated into the rough-and-ready, jokey, testerone-powered environment of US military life. Almost without exception, they stated that they had been well-treated by their US employers, and many (even among those who had apparently received no payment) spoke with evident affection about the American officers whom they had served as ‘houseboys’. Often, however, they were hazy about the names of the Americans, while many Americans knew the Japanese only by nickname: as ‘Benny’, ‘Charley’, ‘Corky’, ‘Peanuts’, ‘Junior’.

The line between fraternization and infantilization, cameraderie and exploitation was thin and wavering. A man named Yamada from Tokyo told his interviewers that he had gone to Korea with US military from the base where he worked as a driver. He was issued a carbine, and used it when the ‘outfit became trapped and we had to fight for our lives’. He had somehow become separated from his US comrades during the occupation of Pyongyang. After wandering alone for a while, he met an acquaintance who helped to arrange for him to work for the 8th Engineers, with whom he remained until he was repatriated to Japan early in 1951.35 An officer from the 8th Engineers, however, told the story a little differently. He had heard that Yamada had been part of a secret mission to bring convoys of military vehicles from Japan to Korea, had been captured by North Korean forces but escaped, and was picked up by an 8th Engineer security patrol. He continued, ‘the platoon leader informed me that this man was what he called a “comical” Japanese and that the men wanted to keep him around, that he was a willing worker, and consequently I said they could keep him in the platoon’.36

As the stories of Yamada, Takatsu and others show, the US military-controlled islands that dotted the terrain of Northeast Asia were not distinct but were linked to one another by invisible bridges, so that, at a time when it was virtually impossible for Japanese civilians to travel legally to Korea or for Korean civilians to travel legally to Japan, the occupants of bases flowed between one military island and another, sliding over the Japan-South Korea borderline as though it did not exist. Several of the Japanese serving in Korea in late 1950 to early 1951 had made multiple trips back and forth between between the two countries in US troop transports.

The flows of Japanese base workers into Korea also intersected with flows of Korean combattants between US bases in Japan and Korea. In the early stages of the Korean War, the US military cooperated with Mindan, the pro-South Korean community organization in Japan, to recruit ethnic Koreans living in Japan to fight on the southern side. Ambitious targets of as many as 50,000 recruits (out of a total ethnic Korean population of around 600,000) were suggested, but the final number was a more modest figure of 644 volunteers, of whom 135 were killed or went missing in action.37 In October 1950, the US military withdrew its support for schemes to recruit Koreans in Japan for military service and war work, but between August and October 1950, hundreds of Koreans living in Japan had been given military training inside US bases before being shipped to the battle zone.

When the recruitment scheme started, some Japanese men also presented themselves at Mindan offices to volunteer for service in Korea. At the organization’s Hokkaido branch office in Hakodate, for example, twenty of the sixty men who had volunteered for service by 8 July were Japanese, many of them former junior officers in the Japanese imperial army.38 Although these volunteers were turned away, a few Japanese did in fact join the Korean recruits in training, and went with them to fight Korea. A Japanese man from Fukuoka, for example, volunteered via Mindan and, with the apparent approval of the occupation authorities, was trained alongside some 120 Korean volunteers at a US base in Japan and sent to the Korean war front; but his total inability to speak Korean proved a handicap, and he ended up working as a ‘houseboy’ for a senior Korean military officer.39

One of the ironies of this fractured postwar world was the fact that, although Koreans in Japan were encouraged to fight for their ancestral homeland, many were refused the right to be reunited with their families in Japan once their war service was over. At this time, strict border control policies prevented movement between the two countries except in very special circumstances, and although the occupation authorities were happy to grant special permission for ethnic Korean volunteers to leave Japan, both they and the Japanese government were reluctant to give them permission to return.40 This may help to explain problems of identity surrounding some of the Japanese repatriated from the war zone: the Americans who investigated their cases at times had difficulty figuring out who was actually Japanese and who was Korean. At least two of the repatriated base employees had Japanese fathers and Korean mothers, and one or two may have been Koreans who were claiming to be Japanese in order to secure their return to homes and families in Japan. For example, one man from Sendai identified himself as a Japanese base worker, and explained that he had stowed away on a US military transport to Korea, but was described by his American superior as a Korean born in Japan who had volunteered through the Mindan recruitment program.41

The complexities of the post-colonial Japan-Korea relationship run like tangled threads through these Korean War stories. Even as they fought on the same side in the war, animosities between former colonizers and former colonized remained profound, and sometimes broke to the surface, as in the case of a Japanese base worker known to his American employers as ‘Jones’. A dock foreman responsible for supervising the loading of Japanese labourers onto ships bound for Korean ports, ‘Jones’ had slipped in amongst the labourers and traveled to Incheon, arriving just after the Incheon landing. Like many of the Japanese who traveled to the Korean War front, ‘Jones’ did not remain with a single US military unit, but drifted from one to another, traveling as far as the port of Hamheung in the northeast of the Korean Peninsula. There he joined up with a South Korean military unit who took him south to Busan, but he soon got into a fight with one of the South Korean officers and was arrested and imprisoned in Busan for about two weeks, during which time (as he complained to his American interviewers) he was ‘beaten every day’, despite the fact that he had been wearing ‘an American MP armband’ at the time of his arrest.42

Yet there could also be unexpected moments of concord. Kawamura Kiichiro, who has published a memoir of his experiences of the Korean War, was not a US base employee but a sailor in the Japanese merchant marine, working on a cargo ship at the time when it was conscripted to carry material including explosives to the Korean front. On its first arrival in Busan in July 1950, the ship’s cargo was inspected by a South Korean officer who proceeded to take Kawamura aside and ask him if he had any copies of the Japanese monthly magazines Bungei Shunju or Chuo Koron on board, and whether he could obtain copies of Japanese manuals on seamanship. The officer, who spoke excellent Japanese, missed reading Japanese publications, then unavailable in Korea. Kawamura recalls that from then on he always made sure to bring a supply of Japanese books and magazines with him on his crossings to the Korean War zone.43

The ruins of Japan’s empire were being refashioned into contours determined by the geopolitics of the hot / cold war, but the process was neither instant nor neat, and many lives were caught in the fissures of the shifting tectonic plates of Northeast Asia. Among the Japanese repatriated by US regiments in Korea was a young man from Shikoku, known to his American comrades-in-arms as ‘Shorty’, who surprised his interviewers by telling them that he had been in Korea ever since July 1945. He had been a student at a school for army communication cadets in Japan when, at the age of thirteen and in the final months of the Asia-Pacific War, he was sent for further training to a college in Manchuria. After Japan’s defeat, he joined the mass of Japanese fleeing south through the Korean Peninsula in the hope of boarding repatriation ships in Busan, but ended up stranded in the Korean city of Daegu, where he found work as a labourer before being employed by the US 24th Division in July 1950.44 As his experience reminds us, the carving up of the space of Japanese empire left hundreds of thousands of people stranded on the wrong side of re-drawn frontiers, a plight that was aggravated as new political tensions turned these frontiers into the frontlines of global confrontation.45

The human tragedies that this produced are reflected in one of the most remarkable of all the stories: the testimony of a teenager named Taira who went to Korea with American forces in July 1951 on a personal mission to find his lost sister.46 The Taira siblings had lived with their parents in Thailand until the end of the Asia-Pacific War, when the family was evacuated to China. Their mother had died in childbirth during the latter part of the war, and brother, sister and father were amongst a large contingent of Japanese expelled by China into the northern half of Korea. There they were taken prisoner in September 1945. After a winter confined in a North Korean prison camp, the Tairas and several hundred other prisoners from their camp were allowed out one day for exercise, and seized the opportunity to stage a mass break-out, hiding themselves in long grass to evade their guards. In the confusion Taira and his father and sister fled in different directions and became separated from one another. As he recalled, ‘my father was killed, so I was told… With 300 Japanese people I escaped into South Korea. I was a small boy. An American truck stopped and picked me up. The three American men in the truck took me with them. In Seoul I was put in a camp with other Japanese people. We went to Pusan and then to Japan.’47

Back in Japan, alone and destitute, Taira found work with the US military, and clung to the belief that his sister had survived and might one day find her way home. In the summer of 1951, he heard that many female refugees from North Korea had congregated in the port of Busan, and decided to make his way to war-torn Korea in the faint hope that his sister might be among them. He managed to board a Japanese-crewed ship transporting troops from Sasebo to Busan, and there found employment as a ‘houseboy’ through the local labour office, spending his spare time combing the streets for news of his sister. The quest was in vain. In February 1952, his presence was noticed by the US military authorities and he was repatriated to Japan – one of the last Japanese military employees to be sent home from the Korean War zone.

The experiences of ‘Shorty’ and Taira echo events taking place on the other side of the new Cold War divide. Five years after Japan’s defeat in the Asia-Pacific War, large numbers of Japanese civilians and soldiers still remained stranded in the lost empire, particularly in the region of Northeastern China that had been the Japanese client state of Manchukuo. Around 30,000 Japanese former soldiers are believed to have been incorporated into the Chinese People’s Liberation Army – some recruited against their will, some willing volunteers, many no doubt accepting recruitment because it offered them their best chance of survival.48

Around the time of China’s entry into the Korean War, some of these Japanese soldiers were trained to join the Chinese ‘volunteers’ fighting on the North Korean side. At the last moment, though, the Chinese military command, like its US counterpart, realized that the use of Japanese forces in Korea was likely to cause ‘international complications’ – offending China’s North Korean allies and providing ammunition for South Korean and US propaganda. One Japanese recruit to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army recalls being trained with a unit preparing for a mission in Korea, only to be told at the last moment that his services would not be needed.49 But some Japanese soldiers in Chinese uniform did cross the Yalu River into the Korean War zone with the Chinese ‘volunteers’. The numbers involved are uncertain, and have been estimated at anything from a couple of dozen to over three hundred.50 Among them was a man named Matsushita from Kyushu, who was taken prisoner by the United Nations forces in South Korea – the only Japanese to become a prisoner of war of the southern side in the Korean War.51 A graveyard in the suburbs of Dairen contains the graves of 351 Japanese (along with many more Koreans and Chinese) who are described as having given their lives in the ‘War to Resist America and Aid Korea’ (as the Korean War is known in China). Many of these seem to have been doctors, nurses and others who died of disease and exhaustion while providing support behind the lines.52

‘Mascots’ and Child Soldiers

The occupation authorities’ concerns about Japanese who accompanied US troops to the Korean War focused on the problem of nationality, since Japanese nationals killed or captured on the battlefield might be used by North Korea or China as evidence of Japan’s covert military involvement in the war. But there was also another lurking source of possible embarrassment: an issue not of nationality, but of age. The majority of the Japanese in the war zone were young men in their late teens and twenties, but at least five of those whose cases were recorded by the military on their return to Japan were children, and there are suggestions in the records that other children had also been taken across the border by the US military, both from Japan to Korea and from Korea to Japan.53

Their stories hint at a disturbing and little discussed facet of life in occupied Northeast Asia. Most were orphans or children abandoned by their families. One, aged ‘about fifteen’ when he was returned to Japan in April 1951, had no idea where he was born and no memory of his parents.54 He had been taken to Korea by an American lieutenant who gave him the nickname ‘Peanuts’ and who, he says, treated him like a father. Together they took part in the Incheon Landing and advanced into North Korea. The lieutnant moved from the 32nd Infantry to X Corps, taking ‘Peanuts’ with him, but soon after was was wounded and evacuated to Japan for treatment. ‘Peanuts’ stayed on in Korea. His testimony reads in part:

Q. What did you do in Korea?

A. When I was with the 32nd Infantry I fought with a rifle but when I went to X Corps I worked in the kitchen….

Q. Were you issued a weapon?

A. Yes, the company issued me with a carbine.

Q. Did you use it?

A. Yes, I don’t remember how many times.55

In February 2012, the South Korean government, after sixty years of denial, finally admitted that almost 30,000 child soldiers aged between fourteen and seventeen had been recruited by the South during the Korean War, a practice that was also common in the North.56 The US military did not, of course, recruit children to their ranks, but a number of units kept child ‘mascots’. One of these was a boy nicknamed ‘Corky’, who was born in Tokyo – the son of a Korean father and a Japanese mother. ‘Corky’ did not carry a weapon or engage in combat, but the interview which he gave on his repatriation to Japan in May 1951 suggests the profoundly disorienting nature of his experience with the military:

Q. What unit did you go to Korea with?

A. I don’t know the unit.

Q. Did you volunteer to go to Korea?

A. Yes, I asked the Colonel.

Q. What was the Colonel’s name?

A. I don’t know. I called him Papa San.

The interviewer notes at the end of ‘Corky’s’ testimony: ‘This boy is only 10 years old and understands very little English and also very little Japanese. It was difficult to interrogate him, even with an interpreter.’57

In a world full of homeless and abandoned children, the individuals and units which adopted child ‘mascots’ may have done so with the best of intentions, but the potential for abuse is also glaringly obvious. Casual cruelty, kindness and the miseries of childhood in the shadow of war are all evident in the brief written record of a Japanese boy called Mamoru, who was adopted as a mascot by the US Headquarters Special Troops Dispensary after he was found alone and crying in a street in Korea in November 1950. Mamoru was nine years old and both his parents had died soon after the end of the Asia-Pacific War. In July 1950 he had been taken to Korea by an unnamed American military unit based in Shimane Prefecture, only to be abandoned in the battlefields of Daegu about ten days after landing at Busan. A corporal in a signals corps then picked him up and ‘kept the boy for about a month and took him to Pyongyang where he was again left on his own’. Another US soldier took him along with ten or so other children to an orphanage in Seoul, from which Mamoru escaped in the hope of finding a way back to Japan. Finally, some six months after his arrival in Korea, Mamoru was taken under the wing of a member of the Dispensary staff who helped rescue him from his plight by tracking down the child’s surviving relatives and arranging his return to Japan.58

Not all were so lucky. One thirteen-year-old, who laboriously signed his name on his record of interview as ‘Mr. Tea’, described how he had first been taken from Japan to Korea as a ‘mascot’ of a US Military Police unit late in 1945 – that is, when he was six or seven years old. Both his parents had been killed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. In Korea, he said, he had been passed from one unit to another, spending periods of time with a military medical unit in Seoul, KMAG (the Korean Military Advisory Group), the US marines in Busan (who took him with them as they advanced to Seoul), and the 87th Ordinance Battalion. Although he was returned to Japan in February 1951, there is no evidence that he had any family left to care for him there, and no indication of what happened to him subsequently.59

And then there was ‘Jimmy’, who was twelve in July 1951 and had lost both his parents in the bombing of Tokyo. Jimmy had been taken to Korea in 1949 by a man whose name is not recorded:

Q. Was he an officer or a GI?

A. I don’t know. I was just with him about ten days before we went to Korea.

Q. How did you happen to go to Korea? Did you ask to go?

A. I didn’t ask anything. The man asked me to go and put me in a barracks bag. 60

He stayed with the man in Korea for about a month before going to the 23rd Infantry, where he became a houseboy for an officer, again for about a month. He then moved to the supply section and then to the motor pool, and finally to the 19th Military Police Battalion.

Q. Were the Americans and GIs nice to you?

A. Yes, American GI were good to me.

Q. What did you do, run errands for them, shine shoes, etc?

A. No, sir, I was just a mascot.

Q. Did they ever give you a gun to shoot?

A. They gave me a carbine.

Q. Did you shoot the gun?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you shoot at any of the North Koreans or Chinese?

A. Yes, Chinese. Maybe three or four Chinese.

Q. Did you kill them?

A. Yes.

The interview ends, like others, with the offer of a job with the US occupation forces in Japan, and a reminder of the need for silence.

Q. Jimmy, all the questions I asked you are about your experience in Korea. I don’t want you to tell anyone about your trip.

A. I understand.

Some 7500 of the child soldiers who fought with South Korean forces in the war are still alive today. It is very possible that some of the child ‘mascots’ and the adult Japanese who went to Korea with US forces are also still alive, and for that reason I have a avoided giving their full names. They have heeded the caution they received over sixty years ago, and maintain their silence to the present day.

Conclusion

Even before the signing of the US-Japan Security Treaty in 1951, then, Japan had already been drawn into a very active military alliance with the US forces fighting in Korea. For many in Japan the Korean War may have seemed a ‘fire on the other shore’ [taigan no kaji] – a distant event that affected them only indirectly, both by promoting economic growth and by tying Japan inextricably into the US military order. But for some, it was a moment of fear, violence and even death, as the recently disarmed Japanese once again took up the gun to fight in a war whose hidden dimensions are still coming to light, sixty years after the event. The combatants whose experiences are described in this article experienced the Korean War as a conflict which emerged almost seamlessly out of the violence of the Pacific War, but as a conflict in which Japanese played a very different role – the half-hidden, profoundly subordinate and ironically symbolic role of armed “houseboys”.

Japan’s direct participation in the Korean War was at its peak during the first six months of the conflict. Concerns about the secret Japanese minesweeping operation heightened following the sinking of a minesweeper, the MS 14, on 17 October 1950, and major Japanese involvement in minesweeping was halted in December of that year, though Japanese sailors continued to participate in minesweeping missions on a smaller scale into 1951.61 By mid-1951, almost all the Japanese nationals who had been taken to Korea with American forces were also back home: the last stragglers seem to have been repatriated early in 1952, and one of the two Japanese prisoners-of-war in North Korea arrived home in August 1953.

Meanwhile, SCAP had established a 75,000 man Japanese ‘National Police Reserve’ [keisatsu yobitai] – forerunner of today’s Self-Defense Force, and despite its name an unmistakably military institution – to take over roles reliquished by US forces deployed to Korea. Japan’s maritime defense force was simultaneously expanded to 8,000.62 The US military was also turning its attention to other forms of Korean War cooperation with Japan, particularly to the outsourcing of transportation, armaments manufacture and ordinance supply to Japanese firms. Although Japanese industry had officially been ‘demilitarized’ during the occupation, by late 1951 the US military was increasingly entering into secret contracts with Japanese firms for the supply of ‘certain types of war material’ including ‘specified weapons and ammunition’.63 As well as supplying such things as fuel tanks and napalm tanks for US F80 fighter planes, Japanese companies were also contracted to provide a wide range of military support services including training equipment and facilities for US troops preparing for combat.64 In many ways, indeed, the outsourcing of military tasks to private companies, which was to be such a future staple of later wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere, was already becoming established in the US-Japan military relationship during the Korean War.

The pattern set in the latter stages of the war provided the template for the incorporation of Japan into the global US network of alliances in a form that continues to the present day. The Korean War itself has remained unfinished, with no peace treaty ever concluded between the belligerents. Memories of the war remain profoundly divided, and Japan’s full role in the conflict has never officially been acknowledged either by the Japanese or by the US government. Six decades after the Korean War, addressing the war’s long-hidden facets may constitute one step towards its long-delayed conclusion, and towards the making at last of a post-Korean War regional order.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History in the Division of Pacific and Asian History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, and a Japan Focus associate. Her most recent books are Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era and To the Diamond Mountains: A Hundred-Year Journey Through China and Korea.

Recommended citation: Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Post-War Warriors: Japanese Combatants in the Korean War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 31, No. 1, July 30, 2012.

Articles on related topics:

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Guarding the Borders of Japan: Occupation, Korean War and Frontier Controls

• Charles K. Armstrong, The Destruction and Reconstruction of North Korea, 1950 – 1960

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, The Forgotten Japanese in North Korea: Beyond the Politics of Abduction

• Mark Caprio, Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War

• Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas

• Han Kyung-Koo, Legacies of War

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Refugees, Abductees, “Returnees”: Human Rights in Japan-North Korea Relations

• Glenda S. Roberts, Labor Migration to Japan: Comparative Perspectives on Demography and the Sense of Crisis

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Invisible Immigrants: Undocumented Migration and Border Controls in Early Postwar Japan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article is based on research conducted as part of a collaborative research project on the Korean War in regional context, supported by the generosity of the Australian Research Council.

NOTES

1 Cited from the Constitution of Japan, English version reproduced in Glenn D. Hook and Gavan McCormack eds., Japan’s Contested Constitution: Documents and Analysis, London and New York: Routledge, 2001, p. 191.

2 See Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945-1947, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1981, ch. 5; Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War: The Roaring of the Cataract, 1947-1950, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1990, chs. 2 and 5; Reinhardt Drifte, ‘Japan’s Involvement in the Korean War’, in J. Cotton and I. Neary eds., The Korean War in History, Manchester, University of Manchester Press, 1989, pp. 20-34; Wada Haruki, Chosen Senso Zenshi, Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 2002, pp. 160-167; Nishimura Hideki, Osaka de Tatakatta Chosen Senso: Suita Hirakata Jiken no Seishun Gunzo, Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 2004; Onuma Hisao ed., Chosen Senso to Nihon, Tokyo, Shinkansha, 2006; and Ishimaru Yasuzo, ‘Chosen Senso to Nihon no Kakawari: Wasuresarareta Kaijo Yuso’, Senshi Kenkyu Nenpo, no. 11, March 2008.

3 Hajimu Masuda, ‘Fear of World War III: Social Politics of Japan’s Rearmament and Peace Movements’, Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 47, no.3, 2012, pp. 551-571.

4 To give just a couple of examples, the postwar volume of Kodansha’s multivolume Nihon no Rekishi contains not a single reference to any Japanese involvement or death in the Korean War. Indeed, it discusses the war only in passing, in terms of its effects on Japanese rearmament, the creation of the US-Japan alliance and the dismissal of General MacArthur; see Kawano Yasuko, Sengo to Kodo Seicho no Shuen: Nihon no Rekishi 24, Tokyo, Kodansha, 2002. The more recently published Senryoka Nihon, coauthored by four prominent public commentators who lived through the occupation, contains a chapter on the Korean War, but although this emphasizes the impact of the US military presence on Japanese society, it depicts Japan as standing ‘outside’ the conflict and reaping the collateral advantages and disadvantages of a war fought by others in a foreign land; see Hando Kazutoshi, Takeuchi Shuji, Hosaka Masayasu and Matsumoto Kenichi, Senryoka Nihon, Tokyo, Chikuma Shobo, 2009, ch. 15; A similar pattern is found in many standard texts on the Korean War. For example, Michael Varhola’s 2000 overview of the war, Fire and Ice, for example, meticulously details the 339 Australians, 121 Ethiopians, 101 Belgians, 46 New Zealanders, 12 Greeks, 2 citizens of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and others killed in the conflict, but makes no mention of any Japanese involvement in the war at all; see Michael J. Varhola, Fire and Ice: The Korean War 1950-1953, Savas, 2000, particularly ch. 7. On Yoshida’s comment, see John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, New York, W. W. Norton, 1999, p. 541.

5 One of the very few general histories of postwar Japan that does acknowledge the formative impact of military involvement in the Korean War is Nakamura Masanori’s Sengoshi, Tokyo, Iwanami Shinsho, 2005.

6 ‘Chosen de Senshi shita Ichinihonjin’, Asahi Shimbun, 13 November 1952; ‘No Compensation Given Father of Nippon Youth Killed in Korea’, Nippon Times, 14 November 1952; see also Nishimura, Osaka de Tatakatta Chosen Senso, pp. 111-116.

7 ‘Onaji Kesu wa mada aru: Neo Hiratsuka no Senshi Mondai’, Asahi Shimbun, 14 November 1952.

8 On the Pravda report, see Onuma Hisao, Chosen Senso to Nihon, p. 101.

9 Concerns about this point were repeatedly expressed by America’s Korean War allies. See, for example, telegram from Department of External Affairs to Australian Mission Tokyo, 7 July 1950, in National Archives of Australia, series no. A1838, control symbol 3123/7/27 ‘Korean War – Japan – Policy’.

10 See, for example, Drifte, ‘Japan’s Involvement in the Korean War’, p. 129.

11 ‘Move to Recruit Japanese Veterans’, Canberra Times, 7 August 1950; ‘Japanese, Germans may soon Join US Forces’, Japan News, 12 August 1950.

12 ‘SCAP Expresses Doubt over Use of Japanese Volunteers for Korea’, Japan News, 10 August 1950.

13 Draft telegram from Department of External Affairs, Canberra, to Australian High Commissioner’s Office, London, 18 July 1950, in National Archives of Australia, series no. A1838, control symbol 3123/7/27 ‘Korean War – Japan – Policy’.

14 Memo from office of Major General Weible to Commanding Officer, US Army Hospital, 8162nd Army Unit, Fukuoka, 31 December 1951, ‘Missing Person’, in National Archives and Records Administration [hereafter NARA], College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

15 L. J. Shurtleff, ‘Report of Investigation Concerning the Transportation and/or Utilization of Japanese Nationals by Units of this Command in Korea’, 20-26 January 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 4.

16 Memo from Commanding General 8th Army, 5 January 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

17 The figure of 46 Japanese repatriated to 12 February 1951 is derived from telegram from 8th Army to 2nd Logistic Command, 12 February 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1. The figure of 72 others is calculated from records contained in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46 and Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 11, shelf 2, container 46, folder 105.

18 Tsutsui Kiyoto from Tokushima Prefecture was repatriated in August 1953 after being a prisoner of war in North Korea for about three years. Another Japanese national, Tanigawa Yoshio, and a Korean born in Japan, Yasui Hirofumi, were also reported in the Japanese media as being prisoners of war, but their ultimate fates are not clear. UN figures for prisoners of war exchanged during the Korean War ‘Big Switch’ and ‘Little Switch’ list only one Japanese national being returned by North Korea and China; see ‘Nihonjin Horyo Sokan suru’, Asahi Shimbun, 17 August 1953; ‘“Hitogoto Hazukashii yo”: Horyo no Tsutsui kun yatto Kaeru’, Asahi Shimbun, 24 August 1953; ‘“Nihonjin Horyo wa Genki”’, Asahi Shimbun, 5 September 1953

19 Onuma, Chosen Senso to Nihon, pp. 104-107; Suzuki Hidetaka, ‘Chosen Kaiiki ni Shitsugeki shita Nihon Tokubetsu Sokaitai: Sono Hikari to Kage’, Senshi Kenkyu Nenpo, no 8, March 2005, pp. 26-46.

20 Ishimaru, ‘Chosen Senso to Nihon no Kakawari’.

21 Record of debate of the National Diet Lower House Labour Committee, 7 March 1951, Kokkai Gijiroku, available online at http://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/

22 Ishimaru, ‘Chosen Senso to Nihon no Kakawari’, p. 34.

23 ‘Chosen Kichi ni Nihonjin Romusha’, Asahi Shimbun, 25 January 1953.

24 Ishimaru, ‘Chosen Senso to Nihon no Kakawari’, p. 35.

25 Testimony (recall) of Marvin R. Kohler, 1st Cavalry Division, 27 January 1951, in L. J. Shurtleff, ‘Report of Investigation Concerning the Transportation and/or Utilization of Japanese Nationals’.

26 Record of Interview of T. Kato, n.d., in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1. NB Names of the Japanese concerned are spelled as in the records of interview throughout this article.

27 Record of interview of T. Ueno, 17 Feb. 1951, in in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

28 Record of interview of S. Nagano, 22 February 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

29 Record of interview of T. Kato, n.d., in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

30 Record of interview of T. Takayama, 23 February 1951, and record of interview of S. Kobayashi, 23 February 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

31 Record of interview of T. Ueno, 17 Feb. 1951

32 Record of interview of K. Takatsu, 18 December 1950, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 3.

33 Statement of T. Katoda, 14 March 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

34 Record of interview of T. Ito, 7 July 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 2.

35 Record of interview of N. Yamada, 17 February 1951, in L. J. Shurtleff, ‘Report of Investigation Concerning the Transportation and/or Utilization of Japanese Nationals’.

36 Testimony of Sgt. D. Goldberg, in L. J. Shurtleff, ‘Report of Investigation Concerning the Transportation and/or Utilization of Japanese Nationals’.

37 Kim Chan-jung, Zainichi Giyuhei Kikan sezu: Chosen Senso Hishi, Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 2007, p. 6.

38 Onuma, Chosen Senso to Nihon, pp. 98-99; see also Kim, Zainichi Giyuhei, pp. 12-14.

39 Telegram to Commanding General EUSAK, January 1951 (day not given), in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

40 See Kim, Zainichi Giyuhei; Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, particularly pp. 140-142.

41 Record of interview of T. Ohara, 22 February 1951, and telegram from Capt. C. D. Armentrout to Commanding Officer 7th Infantry Division, 1 January 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

42 Record of interview of T. Kato, n.d.

43 Kawamura Kiichiro, Nihonjin Senin ga Mita Chosen Senso, Tokyo, Asahi Communications, 2007, pp. 39-43

44 Record of interview of T. Kiyama, 25 August 1951, and memo from HQ 24th Infantry Division to Commanding General EUSAK, 19 August 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 2.

45 See Mariko Tamanoi, Memory Maps: The State and Manchuria in Postwar Japan, Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2009; Lori Watt, When Empire Comes Home: Repatriation and Reintegration in Postwar Japan, Cambridge Mass., Harvard University Press, 2009

46 Taira’s story is narrated in record of interview of T. Taira, 1 February 1952, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 11, shelf 2, container 105, and testimony of Major Gordon L. Staker, 30 January 1952, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 2.

47 Record of interview of T. Taira, 1 February 1952.

48 See Furukawa Mantaro, Chugokujin Zanryu Nihonhei no Kiroku, Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 1994; Gomi Yoji, ‘Nihonjin mo Sansen shita Chosen Senso’, Hikari Sase! Kita Chosen Shuyojo Kokka kara no Kaiho o Mezasu Rironshi, no. 6, December 2010, pp. 109-117. See also Mariko Asano Tamanoi, “Japanese War Orphans and the Challenges of Repatriation in Post-Colonial East Asia.“

49 Furukawa, Chugokujin Zanryu Nihonhei, pp. 94-97.

50 Furukawa, Chugokujin Zanryu Nihonhei, p. 98.

51 ‘Kokufu – Chukyo – Kokurengun e: Ikite ita Heitai’, Mainichi Shimbun, 29 January 1952.

52 Gomi, ‘Nihonjin mo Sansen shita Chosen Senso’, pp. 114-117.

53 A memo from M. M. Kernan of HQ Japan Logistical Command to Commander-in-Chief Far East, 25 October 1951, for example, outlines a decision to refuse a request by an American serviceman to enter Japan in order to adopt a Japanese orphan. Reasons for the refusal included the fact that the serviceman’s record was considered problematic, and that the orphan was believed to have ‘been back and forth between Japan and Korea on at least two occasions and apparently with the collaboration of American officials’. (Memo contained in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 2). A letter from E. M. Evans, HQ Camp Kokura, to the Office of the Provost Marshall, 17 January 1951, also speaks of a Japanese national in his late teens as having been ‘brought to Japan with a Korean boy’ by troops returning for rest and recreation to Camp Kokura. (Letter contained in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 3).

54 Memo from D. W. Prewitt, X Corps, to Commanding General X Corps, 26 April 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

55 Record of interview of Y. S., 8 May 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1. (For reasons of privacy, names of child interviewees have been replaced with initials).

56 ‘7,500 Child Soldiers from Korean War Still Alive’, Chosun Daily (English edition), 21 June 2012.

57 Record of interview of C. K., 23 May 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

58 Memo from Maj. R. Boule to Headquarters EUSAK, ‘Return of Japanese National Boy to Japan’, 6 March 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 1.

59 Record of interview of Y. H., 17 February 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 3.

60 Quotations here and below are from record of interview of T. S., 25 July 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46, folder 2.

61 Suzuki, ‘Chosen Kaiiki ni Shitsugeki shita Nihon Tokubetsu Sokaitai’; Nishimura, Osaka de Tatakatta Chosen Senso, pp. 99-101.

62 Drifte, ‘Japan’s Involvement in the Korean War’, p. 127.

63 Memo to Assistant Chief of Staff, Department of the Army, Washington, 5 December 1951, [63] Quotations here and below are from record of interview of T. S., 25 July 1951, in NARA, College Park, Records of GHQ, FEC, SCAP and UNC, record group 554, stack area 290, row 50, compartment 17, shelf 3, container 46.

64 The fuel and napalm tanks were manufactured by Chu-Nihon Heavy Industries, part of the dissolved Mitsubishi zaibatsu which later rejoined the reconstituted Mitsubishi Heavy Industries; see Ashida Shigeru, ‘Chosen Senso to Nihon: Nihon no Yakuwari to Nihon e no Eikyo’, Senshi Kenkyu Nempo, no. 8, March 2005, pp. 103-126, citation from p. 116.