The Fukushima nuclear accident spurred expectations in the Japanese public and around the world that Japan would pull the plug on nuclear energy. Indeed, in July 2011 Prime Minister Kan Naoto announced that he no longer believed that nuclear reactors could be operated safely in Japan because it is so prone to devastating earthquakes and tsunami; by May 2012 all of Japan’s 50 viable reactors were shut down for safety inspections. Plans to boost nuclear energy to 50% of Japan’s electricity generating capacity were scrapped and in 2012 the government introduced subsidies to boost renewable energy. Incredibly, an aroused public took to the streets in the largest display of activism since the turbulent 1960s as the summer of discontent featured numerous demonstrations involving hundreds of thousands of anti-nuclear protestors. Moreover, public opinion polls indicate that more than 70% of Japanese want to phase out nuclear energy by 2030.

The government went through the motions of consulting public opinion, but found that 81% of those it surveyed came up with the ‘wrong’ answer, favoring the zero nuclear option by 2030. Ironically, the government then held seminars to educate selected citizens about the pros and cons of nuclear energy, hoping that this would produce a better result but the before and after surveys reveal that the more people know about nuclear energy the less likely they are to support it. However, the public was never going to have the final say on something as important as national energy strategy and the nuclear village has intervened to ‘save’ the people from their ‘misguided’ views on the dangers of nuclear energy.

Reverse Course

As I argued in early September in a lengthy analysis of “Japan’s Nuclear Village”, the deck is stacked in favor of the pro-nuclear advocates of the nuclear village and it is unlikely that public opposition will trump the networks of power defending nuclear energy. But the speed and extent of the nuclear village’s revanchism has been stunning. The marginalization of public opinion is evident in three significant policy developments. First, on September 14, 2012 the Noda Cabinet appeared to endorse a gradual phase-out of nuclear power by the late 2030s, but within days quickly disavowed this plan under heavy pressure from business lobby groups. (Asahi 9/19/2012, Asahi 10/4/2012, Japan Times, 10/6/12) It has not officially endorsed a new national energy plan and explained that any decision on energy policy is subject to ongoing review in light of future developments. PM Noda expressed the ambiguity thus: “We need a strategy with both a firm direction and the flexibility to respond to circumstances; while its base line will not waver, it will not restrict future policy excessively.” Precisely. The Asahi concludes that the nuclear phase-out is now just a “hollow promise”, pointing out that the lack of Cabinet endorsement means that the Innovative Strategy for Energy and Environment is not binding on future governments and will impede implementation. (Asahi 9/19/2012)

|

|

Second, having muddied the waters on energy policy, the Cabinet then shifted responsibility for any future reactor restarts to the new Nuclear Regulatory Authority and reactor hosting communities. The head of the NRA initially demurred, stating that his organization merely assesses operational safety and does not have responsibility for reactor restarts. He later recanted, but pointed out that utilities also share responsibility for reactor restarts because they have to get local communities to agree. But who, in what communities, gets to decide? Now that the NRA widened the designated evacuation zone around nuclear plants to 30 km, the towns near reactors also want more say in restarts since they bear the same risks, but don’t receive the subsidies given to reactor hosting communities. Because lines of responsibility and authority are now dispersed and blurred, it is not clear where the buck stops, a strategy for undermining opposition.

And what about the cabinet’s declaration that the government would strictly adhere to the law on decommissioning reactors over 40 years old? Well on the morning of September 18 the Chief Cabinet Secretary said yes, but later that day he said that decision is up to the NRA. The 40-year rule has a major loophole that allows renewal of the operating license at the discretion of regulators, the same ones tarnished by three major investigations that found that cozy and collusive relations between nuclear watchdog authorities and the utilities compromised safety in Japan’s nuclear plants and was a major factor leading to the accident at Fukushima. (Kingston 2012b) Given regulatory capture in Japan, meaning that nuclear regulators have long regulated in favor of the regulated, there are good reasons to doubt that stricter guidelines will be resolutely implemented. Extending the operating licenses for aging, old technology reactors may be dangerous, but profitable for the utilities. It is worth recalling that risk is socialized and profits privatized in the nuclear industry, meaning that in the event of a major accident, taxpayers will foot the bill. (Ramseyer 2012)

Inertia as Policy

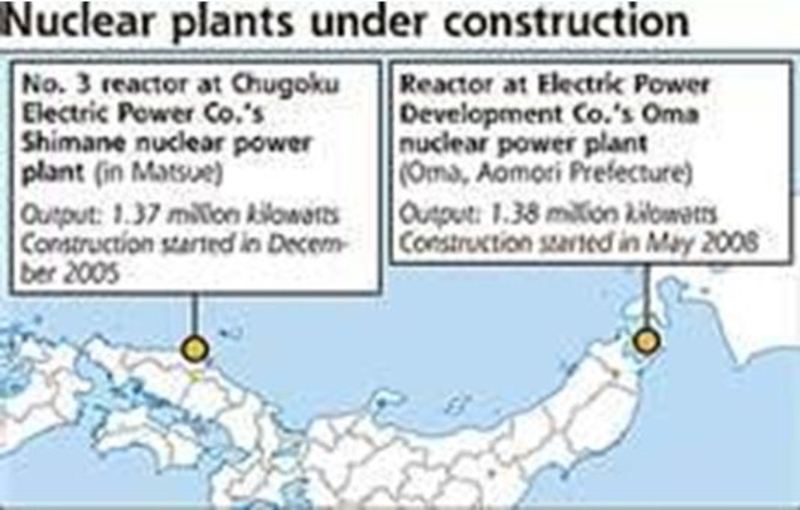

The third development suggesting that the nuclear village has prevailed is the government’s decision allowing completion of three new nuclear reactor projects that had been suspended following Fukushima. METI Minister Edano Yukio argued disingenuously that the government has no authority to cancel licenses previously issued. Well, except if they want to.

|

Approving construction of three new reactors in the face of overwhelming public opposition to nuclear energy is a sign that pulling the plug on nuclear energy has been abandoned in favor of business as usual.

In addition to the Oma plant where construction is about 40% complete, one in Shimane is 90% done and may come online as soon as 2014. The other project in Higashidori also in Aomori is still in the initial stages and only 10% complete; analysts doubt whether this project will proceed because the remaining financial hurdles are too high.

As the Financial Times reports, “Kenichi Oshima, a nuclear policy expert at Ritsumeikan University, says uncertainties about the future cost of operating nuclear plants in Japan weaken the economic case for more atomic power. ‘There will be more costs for safety upgrades, and no one knows what kind of insurance system is going to be put in place. These things will make a big difference to generating costs.’ Since it takes about 40 years for a reactor to recoup its initial building costs, switching off the new plants in the 2030s, around two decades before the end of their normal operating lifespans, would mean accepting major investment losses — something a future government might be unwilling or unable to impose on utilities. ‘Basically, building these reactors would mean reversing the nuclear phase-out,’ Oshima says.” (FT 10/23/2012)

METI Minister Edano Yukio explained that since the government already approved the licenses it was not in a position to cancel the reactor-building projects. Yet, he also stated, “I believe that even under the current legal framework, the government can prevent construction of an unwanted reactor” (Asahi Oct 13, 2012) Apparently, ‘unwanted’ is in the eyes of the beholden. He did not explain how building new reactors is consistent with the Cabinet’s overall objective of eliminating nuclear energy, something he also promotes in his book published the previous month. (Edano 2012) But the capitulation was not complete; the government scrapped nine other nuclear reactor projects that had been approved in the 2010 national energy strategy. At that time the government planned to boost nuclear power to 50% of electricity generating capacity.

Deftly moving to defuse public criticism over the new reactor construction restarts, Edano stated that the government is drafting a new law that would enhance its powers to veto the construction of new power plants. Currently the “independent” NRA has legal authority over approving new reactor construction proposed by the utilities so the new laws might be a strategy for METI to claw back some power; previously NISA held authority for approving nuclear construction projects and was an agency within METI. METI wants the final say on licensing of new projects, but given that it controls subsidies paid to communities agreeing to host nuclear plants, it already has considerable leverage and theoretically could withhold such subsides if its wishes are ignored. Yet, given that former METI/NISA employees constitute a vast majority of the new NRA staff, what are the chances of major differences over nuclear energy issues?

Regulatory Revamp

In September 2012, Japan’s two discredited nuclear regulatory institutions, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) and the Nuclear Safety Commission (NSC) were disbanded and replaced by the Nuclear Regulatory Authority (NRA) with a staff of 480. But the NRA is more a reorganization than a significant reform as 460 of its staff were transferred from NISA and the NSC. NISA was complicit in the utilities systematically downplaying safety and not adopting stricter international safety guidelines and cover-ups of falsified repair and maintenance records. NISA was also ineffective during the 3.11 crisis and failed to provide timely and accurate advice to PM Kan Naoto as the crisis almost spiraled out of control. Precisely because NISA lost its credibility due to a series of revelations about its timid and flawed regulatory record, post-Fukushima it was imperative to establish a credible nuclear watchdog to lessen public distrust and improve operational safety through more robust monitoring. The NRA has a deep hole to climb out of, especially given that it employs many of the same regulators who had been regulating in favor of the regulated and were responsible for lax monitoring and overlooking safety lapses. Can the NRA escape regulatory capture, nurture a culture of safety and crack the whip on the powerful utilities? Lets hope so.

The new nuclear regulatory safety czar is Tanaka Shunichi, former vice chairman of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission, a key organization that strongly influences government nuclear policy. He also served as president of the Atomic Energy Society, an academic society that advocates nuclear energy. In Diet confirmation hearings in July 2012, Tanaka acknowledged that he is a member of Japan’s nuclear village, an admission that attracted public criticism, but did not impede his appointment. Tanaka stated he favors decommissioning older reactors (>40 years of operation) and tightening up the provisional safety guidelines hastily cobbled together by the Noda Cabinet at the end of April 2012. He also testified that he would close the Oi reactors if they are found to be located on active fault lines and said the NRA would get more involved in fault line assessments and not rely on the utilities to probe the matter. (Kyodo 8/2/2012) Perhaps, but owing to his background, many critics are skeptical about whether Tanaka is inclined to play a more robust monitoring role and whether regulatory capture will persist.

The NRA appointed a team of experts to investigate the safety of the Oi reactors (the only two operating in Japan) beginning in November 2012, including a seismologist who has warned of the dangers of an active fault line at the site. Tanaka has also indicated that the NRA will draw up new more stringent safety guidelines by July 2013 that include measures to beef up accident management and disaster prevention in light of Japan’s high seismic risk and bring them into line with international standards. (Asahi 10/18/2012) Madarame Haruki, former head of the now disbanded Nuclear Safety Commission, stunned the nation in February 2012 when he testified in the Diet that government regulatory authorities colluding with the utilities had resisted upgrading safety guidelines to meet stricter international standards, making excuses why they were unnecessary based on overly optimistic risk assessment. (Kingston 2012a)

PM Noda bypassed the Diet in making Tanaka’s appointment, an expedient maneuver allowed when parliament is not in session. However, given that launching of the NRA was intended to regain lost legitimacy for nuclear watchdog authorities, purposely evading Diet oversight was not a promising start. The jury is still out on whether the NRA will nurture a culture of safety in an industry where deceit and cover-up have been standard operating procedures, but the bar is set low for it to improve on the performance of its predecessor NISA. Given that seven of Japan’s ten utilities have admitted to falsifying repair and maintenance records on NISA’s watch, the NRA has its work cut out to end the DIY approach to safety compliance that has irresponsibly escalated risk. (Kingston 2012b)

Victory

These developments in the autumn of 2012 constitute a major victory for the nuclear village as the decision in favor of policy drift on energy policy is a snub to public opinion and provides opportunities for more extensive lobbying. PM Noda’s cabinet has zigzagged on nuclear energy policy and has shrugged off public opinion as it woos Keidanren, a major pillar of the nuclear village. As Jonathan Soble observes, “Under pressure from pro-nuclear business groups, it resolved to act “flexibly” and with “constant verification and revision” — hedges that might keep the nuclear industry in business indefinitely.” (Financial Times 10/24/2012) The Cabinet caved on its pledge to phase out nuclear energy just one day after the nation’s three largest business groups Keidanren (Japan Business Federation), Keizai Doyukai (Japan Association of Corporate Executives) and the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry issued a joint statement complaining that the government had ignored their objections to a nuclear phase-out.Keidanren Chairman Yonekura Hiromasa inveighed, “We object to the abolition of nuclear power from the standpoint of protecting jobs and people’s livelihoods. It is highly regrettable that our argument was comprehensively dismissed.” (Asahi 9/19/2012) Publically admonished by the nuclear village elders, the Cabinet promptly flip-flopped.

This was a major victory for the nuclear village as a “no decision” opens opportunities to lobby politicians and shape public opinion. Policy drift and biding time play to the advantages and interests of the nuclear village; most of the bad news came out in 2011-2012 and now it is hoping that anger and outrage will diminish. The nuclear village is also hopeful that the LDP will regain power and resume support for nuclear energy as a centerpiece of national energy strategy.

Blurring responsibility over reactor restarts is a strategy for depoliticizing such decisions, removing the prime minister as a handy target for anti-nuclear protests and insulating politicians from public pressure; now they can say, “we hear you, but its out of our hands.” As Roger Pulvers points out, “This, though, is the strategy of Japan’s political leaders, bureaucratic controllers and industrial forces: Confuse the public with ambiguous signals,

feigning an interest in opposition arguments; issue guidelines that assuage

public anxieties; and send the captains of industry out to assure the people

that their welfare — not instinctive greed — is their primary concern.” (Japan Times 10/21/2012). Pulvers adds, “They are trying once again, as they did in the 1950s and ’60s, to railroad policy in favor of nuclear energy while maintaining the pretense of open mindedness, debate and concern. “

Watching the political elite wriggle out of taking responsibility is instructive not only because it sows confusion, but also because key government actors are demonstrating that they are worried that they might be held accountable, not exactly a resounding vote of confidence in nuclear safety. And, by edging out of the control room, the political elite is leaving nuclear energy policy up to the bureaucrats and utilities, the very institutions that government investigations hold responsible for the debacle at Fukushima.

Guilty

Three major investigations into the Fukushima accident were released in 2012, detailing the absence of a culture of safety in the nuclear industry and the dangerous consequences of regulatory capture. (Kingston 2012b) All three investigations assert that the meltdowns were preventable and refuted Tokyo Electric Power Company’s (TEPCO) claim that the massive tsunami was an inconceivable black swan event that caused the three meltdowns and hydrogen explosions. Finally, on October 12, 2012 TEPCO abandoned its tsunami defense and acknowledged that the nuclear accident was caused by its excessively optimistic risk assessments, shortchanging of safety and training, and failure to adopt appropriate countermeasures.

|

|

TEPCO confessed that it had erred in not adopting stricter safety measures and could have prevented the nuclear crisis had it done so. (Asahi 10/13/2012) TEPCO’s in-house investigation report issued in mid-2012 flatly denied responsibility or compromising safety, but the subsequent TEPCO reform panel including international experts came to completely different conclusions based on the utility’s internal documents. TEPCO admitted what had been extensively reported about its downplaying of tsunami risk, longstanding resistance to adopting international safety standards and an institutionalized inclination to cut corners to save money in ways that jeopardized safety. It also admitted that employees were not properly trained and lacked crisis management skills. TEPCO explained that it did not manage risk properly because it feared that any measures to improve safety at the Fukushima plant would stoke the anti-nuclear movement, interfere with operations, raise costs and create legal and political problems. This mea culpa is an extraordinary development, one that has poured fuel on the fires of discontent smoldering in contemporary Japan and exposed the flaws, dissembling and wrongdoing of the nuclear village.

TEPCO concedes it had been lying to the government and public from the early hours of the crisis in March 2011 and exposed its own investigation as a sham designed to deceive. It does not deserve any kudos for this belated admission of what was already widely known and proven. It appears to be a strategy to show that TEPCO is really reforming and win approval for restarting its idled reactors at Kashiwazaki, Niigata. Now that TEPCO is nationalized, at a cost of $45 billion as of May, it is insulated from legal consequences, but its mea culpa does raise questions of why it is being allowed to exercise considerable autonomy in carrying out reforms and restructuring. TEPCO is probably the least trusted firm in Japan for very good reasons; it considered and decided not to take measures that would have prevented the meltdowns, its workers were not properly trained to operate emergency systems so they exacerbated the crisis while workers and surrounding communities were exposed to high levels of radiation and over 100,000 have been displaced from their homes and it remains uncertain when if ever they will be able to return. (Birmingham and McNeill 2012) This may not constitute criminal negligence, but it is certainly a disgraceful record. And, the prolonged denials and cover-up of responsibility have further tarnished the company’s sullied reputation. As Shimokobe Katsuhiko, the new TEPCO chairman, admits, “For people in society, just the thought of Tepco’s name is disgusting.” (FT 10/21/2012)

Shift Right

Given the unpopularity of the Noda government, and overwhelming public support for the zero option, it is revealing that the DPJ has not played the anti-nuclear card to woo voters. While the DPJ nominally takes an anti-nuclear stance, its actions have been quite supportive of nuclear energy and not consistent with its pledge to phase out nuclear energy. This signifies that political leaders are more willing to risk public ire than defy the nuclear village.

The political winds are now blowing in favor of the Village. Current polls suggest that when lower house elections are held (and they must by August 2013) the LDP is likely to emerge on top and will probably form a coalition government. During the LDP party presidency campaign in September 2012, Abe Shinzo, the winner, voiced his support for nuclear energy and restarting idled reactors while the second place finisher Ishiba Shigeru concurred; Abe is now party president and Ishiba is secretary general of the LDP. They lead the party that presided over the establishment and growth of the nuclear industry when all 50 of Japan’s viable nuclear reactors were built. The LDP is a pillar of the nuclear village and can be counted on to use its extensive influence to reinstate nuclear energy as a mainstay in Japan’s energy mix.

The only prominent politician (other than the discredited and fading Ozawa Ichiro) to take an anti-nuclear stance is Hashimoto Toru, the mayor of Osaka who recently launched the Japan Restoration Party. He pledges to phase out nuclear energy in Japan by the 2030s, but supports export of nuclear technology and expertise. There is speculation that he might join an LDP-led coalition government, but his anti-nuclear stance might make this a difficult match. However, in June 2012 Hashimoto, a vocal critic of nuclear power, caved under pressure from the nuclear village and assented to the restart of the Oi reactors so he has a track record of backtracking.

Typhoon Ishihara hit Japan’s staid political world on October 25th as he abruptly announced his resignation as governor of Tokyo. Ishihara Shintaro, 80, announced plans to form a new party along with five other conservative old codgers from the tiny Japan Sunrise Party and indicated he plans to field a number of other candidates in the upcoming lower house elections. The mainstream parties’ reaction to the surprise announcement has been cool, perhaps because he is seen to be more of a wild card than a trump card. He is gaffe-prone and erratic so it’s hard to predict to what extent other parties will collaborate with this bumptious renegade. Although he and Mayor Hashimoto share common ground on revising the Constitution to remove military constraints, and both lambaste the bureaucracy, Ishihara is a pro-nuclear advocate. More importantly, both are prickly and highly egotistical so it is hard to see them developing a working relationship. Abe and the LDP might be a more comfortable fit for Ishihara on policy issues, but his extremism on disputes with China and Korea make him a risky partner.

|

The biggest impact of Ishihara’s return to national politics may be intense media coverage of his provocative views on East Asian relations. His petulant tirades and ability to stir controversy make for good copy and keeps him in the limelight. Back in April, he roiled regional relations by announcing his intention to purchase the disputed Senkaku (Diaoyu) islands, infuriating Beijing. His plans forced the national government to make the purchase, thereby provoking China and causing a spike in bilateral tensions. While critics point out that Ishihara has scored a doozy of an “own goal”, seriously harming the national interest by ratcheting up animosity and inflicting heavy losses on Japanese companies exporting to or operating in China, in some ways he was successful. Ishihara wanted to provoke China, give him an A+ on that, and he managed to shift political discourse to the right by stoking domestic anxieties about a rising China. In doing so, he has fanned negative attitudes towards China and more importantly, raised the heat on ever simmering concerns that Japan is vulnerable and embattled.

The rightward shift in politics, and heightened national anxieties, plays to the nuclear village’s agenda. Deteriorating relations with China (along with island disputes with South Korea and Russia) is prodding a ‘circling of the wagons’ mentality. In this context of fear and antagonism, the siren song of nuclear energy self-sufficiency is more appealing. Not in terms of the logic or realistic prospects, but at an emotional level divorced from a sober calculation of what makes sense. So even if the Japanese public has proven surprisingly assertive and critical of the government’s pro-nuclear policies because of the Fukushima debacle, and three investigations highlight why citizens should remain concerned about safety shortcomings in the nuclear industry, worsening external relations have nurtured a game-changing mood favoring acquiescence to the nuclear village’s dictates.

To be sure, hard-core critics remain resolute, but the larger numbers of people who have been quick to recoil at the seamy realities of the nuclear village, are prone to being influenced by media focus on the economic consequences of rising fuel imports. The resilient nuclear village is biding its time, believing that the summer of 2012 was the peak of dissent. As the ragtag band of anti-nuclear activists plugs on, inspired by public intellectuals such as Oe Kenzaburo, the big question is whether they can continue to galvanize public opposition. The government’s insouciant shrugging off of anti-nuclear public opinion is a demoralizing development, one that demonstrates that the powers that be are not going to roll over. The lessons and legacies of Fukushima are being elbowed aside and the public is seeing how weak they are in the face of power politics. These moves by the nuclear village are a blunt, but unmistakable power play and demonstration of unrepentant strength, “battered but unbowed”, by the institutions that control the commanding heights of policymaking. Under the circumstances, it will not be surprising if the anti-nuclear movement abates and citizens ‘adjust’ to the new circumstances of heightened external threats.

Conclusion

Why has Fukushima not been a game changing event? The institutions of Japan’s nuclear village (principally the utilities, bureaucracy and Diet) enjoy considerable advantages in terms of energy policymaking. They have enormous investments at stake and matching financial resources to sway recalcitrant lawmakers and the public. The nuclear village has openly lobbied the government and actively promoted its case in the media while also working the corridors of power and backrooms where energy policy is decided. (For a less pessimistic assessment, see Johnston 2012) Here the nuclear village enjoys tremendous advantages that explain why it has prevailed over public opinion concerning national energy policy. Its relatively successful damage control is an object lesson in power politics. To some extent the lessons of Fukushima are not being ignored as the utilities are belatedly enacting safety measures that should already have been in place, but a nuclear-free Japan by the 2030s increasingly seems unlikely.

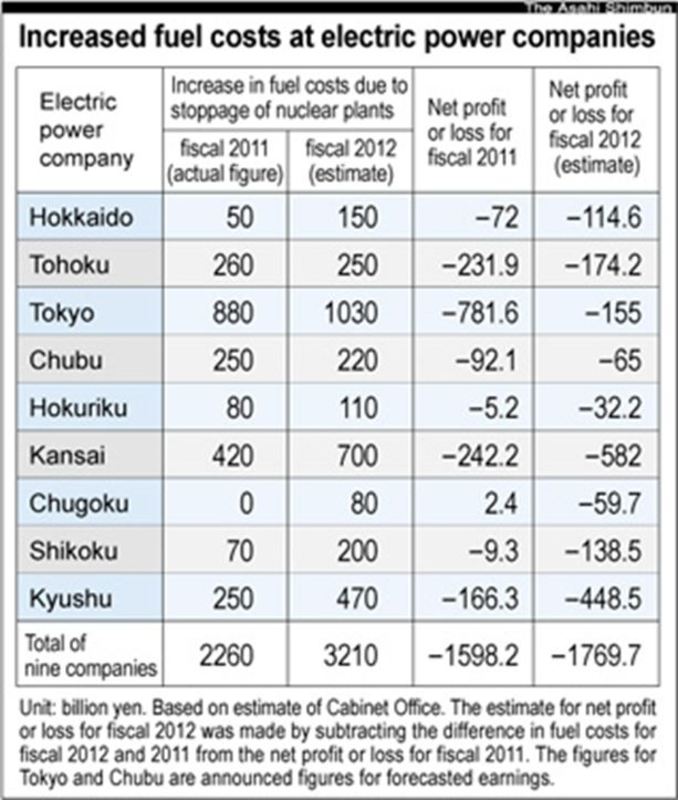

Another reason why nuclear energy remains in play is because the renewable options that are being ramped up will not offset the loss of 29% of Japan’s electricity generating capacity for another two decades. In the meantime, Japan is replacing nuclear power with imported fossil fuels and running up massive trade deficits ($7.2 bn in September, $9.6 bn in August 2012). Fortunately, LNG prices are relatively low and Japan runs a healthy current account surplus, but an economy in a prolonged funk does not need the added cost of soaring fuel bills. The additional LNG purchases to replace idled nuclear reactors mean an increase at least in the short run in greenhouse gas production. This does not mean that Japan is abandoning renewables. Japan’s green revolution will generate jobs, attractive investment returns and economic growth, but politicians know that vision only gets them so far. Although the government is subsidizing expansion of renewables through feed-in-tariffs, the potential economic benefits exceed the current reality.

Elections force politicians to show what they have done lately, not what they hope to accomplish in twenty years. Nuclear energy is just too tempting because all that capacity is just sitting there waiting to be revved up. Yes the backend costs of processing and managing waste are costly, but in the short-term, politicians, bureaucrats and business leaders see cheap energy going to waste while the trade account is awash in red ink. In their eyes, this is not a difficult choice.

Are politicians pushing nuclear energy to save the planet from global warming? Probably not. Nuclear advocates concerns about a surge in Japan’s carbon emissions are exaggerated. Germany demonstrates that it is possible to cut nuclear energy and reduce greenhouse gases at the same time, but this depends on a more robust expansion of renewable energy. It remains possible, however, that Japan will come close to its 25% carbon emissions reduction target by 2020 even without nuclear energy, aided by slow growth, energy conservation, expansion of renewables and greater reliance on LNG. It only produces about 4% of global carbon emissions and has made huge strides in conservation and energy efficiency; between 1979-2009 Japan’s GDP doubled while its industrial sector energy use remained flat. LNG emits only half as much as carbon as coal and is plentiful and cheap, representing an ideal bridging energy as Japan transitions towards renewables. More importantly, greater reliance on LNG and other fossil fuels in Japan will have a minor overall impact as what China, India and the United States do matters much more in terms of global emissions.

Japan’s power network promoting nuclear energy is not planning to go out of business at home or overseas. Indeed, promotion of reactor exports by the Japanese government continues while in 2012 Toshiba increased its stake to 87% in Westinghouse, a major player in the global nuclear industry, along with Hitachi/ GE and Areva/Mitsubishi. Even the ostensibly anti-nuclear maverick politician, Hashimoto Toru, is now plugging nuclear exports and he has a reputation as a bad boy in the political world.

While the large demonstrations and signs of a more robust civil society have drawn considerable attention and stoked a degree of euphoria about the prospects of a green revolution, it is important to bear in mind the substantial obstacles and the short-term economic incentives that drive politicians. The key is that the nuclear village retains veto power over national energy policy and citizens will not get to decide the outcome. At present, there is no party likely to gain power in the next elections that will commit to phasing out nuclear energy over the next few decades.

In July 2013, the NRA plans to have new safety guidelines in place for deciding on reactor restarts and Keidanren is already lobbying to bring idled plants back online. Currently, the two largest parties seem ready to give the green light to reactor restarts, so whatever the election outcome it seems likely there will be increasing pressure on the NRA to get on with it. It may take another nuclear tragedy to derail the nuclear village’s triumphal return. Regrettably, the government and utilities continue to downplay risk, leaving Japan vulnerable to such a scenario.

Sources:

Birmingham, Lucy and David McNeill. (2012). Strong in the Rain. NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Edano, Yukio. (2012) Tatakaretemo Iwaneba Naranai Koto (What I Must Say Even if I Were to be Criticized). Tokyo: Toyo Keizai Shimposha.

Johnston, Eric. Fresh Currents: Japan’s Flow from a Nuclear Past to a Renewable Future.

Kingston, Jeff. (2012a) “Mismanaging Risk and the Fukushima Nuclear Crisis,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 10, Issue 12, No 4, March 19

Kingston, Jeff (2012b).”Japan’s Nuclear Village,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 10, Issue 37, No. 1, September 10 Japan’s

Ramseyer, J. Mark. (2012) “Why Power Companies Build Nuclear Reactors on Fault Lines: The Case of Japan.” Theoretical Inquiries in Law. 13:2 (Jan.) 457-485.

Jeff Kingston is Director of Asian Studies, Temple University Japan. He is the editor of Natural Disaster and Nuclear Crisis in Japan: Response and Recovery after Japan’s 3/11 (Routledge 2012) and author of Contemporary Japan. (2nd edition) (Wiley).

Recommended Citation: Jeff Kingston, ‘Power Politics: Japan’s Resilient Nuclear Village,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 44, No. 1, October 29, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

• Shoko Yoneyama, Life-world: Beyond Fukushima and Minamata

• Iwata Wataru, Nadine Ribault and Thierry Ribault, Thyroid Cancer in Fukushima: Science Subverted in the Service of the State

• Masuda Yoshinobu, From “Black Rain” to “Fukushima”: The Urgency of Internal Exposure Studies

• Shaun Burnie, Matsumura Akio and Murata Mitsuhei, The Highest Risk: Problems of Radiation at Reactor Unit 4, Fukushima Daiichi

• Aileen Mioko Smith, Post-Fukushima Realities and Japan’s Energy Future

• Makiko Segawa, After The Media Has Gone: Fukushima, Suicide and the Legacy of 3.11

• Timothy S. George, Fukushima in Light of Minamata

• Christine Marran, Contamination: From Minamata to Fukushima

• Matthew Penney, Nuclear Nationalism and Fukushima

• Fujioka Atsushi, Understanding the Ongoing Nuclear Disaster in Fukushima:A “Two-Headed Dragon” Descends into the Earth’s Biosphere

• Kodama Tatsuhiko, Radiation Effects on Health: Protect the Children of Fukushima

• Say-Peace Project and Norimatsu Satoko, Protecting Children Against Radiation: Japanese Citizens Take Radiation Protection into Their Own Hands

• Ishimure Michiko, Reborn from the Earth Scarred by Modernity: Minamata Disease and the Miracle of the Human Desire to Live