Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima

Brian Victoria

Abstract: This article explores the longstanding relationship between Buddhism and disasters in Japan, focusing on Buddhism’s role in the aftermath of the Asia-Pacific War and the Tohoku disaster of March 2011. Buddhism is well positioned to address these disasters because of its emphasis on the centrality of suffering derived from the impermanent nature of existence. Further, parallels between certain Buddhist doctrines and their current, disaster-related cultural expressions in Japan are examined. It is also suggested that Japanese Buddhism revisit certain socially regressive doctrinal interpretations.

Keywords: Buddhism, disasters, suffering, impermanence, kamikaze, Fukushima, Asia-Pacific War, tsunami, Stoicism, discrimination

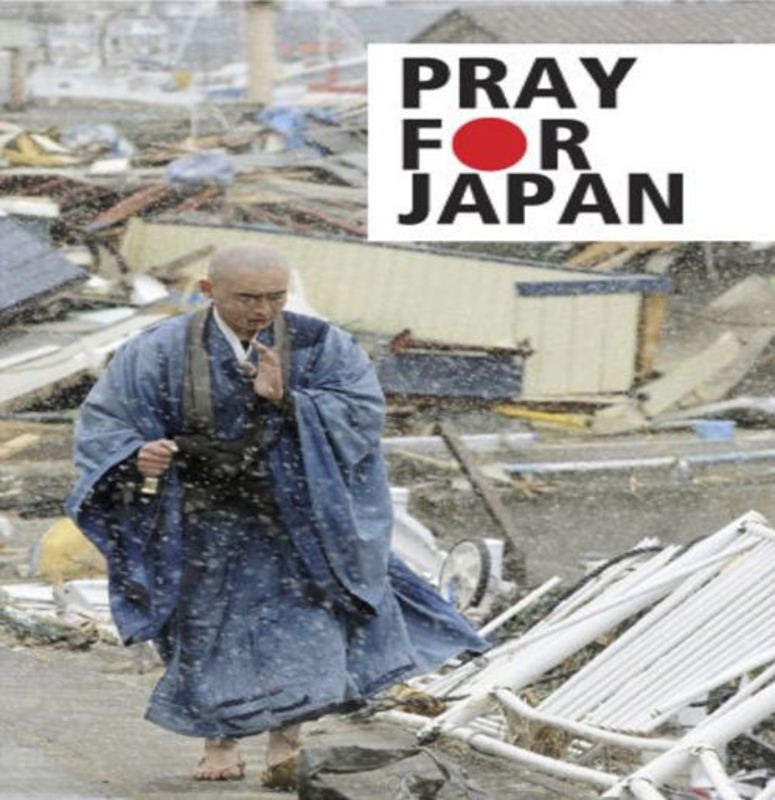

Zen monk reciting sutras amidst tsunami destruction |

It is safe to say that in considering the events of March 11, 2011 including the ongoing disaster at the Dai-ichi Fukushima nuclear power plant, Buddhism is not the first thing that comes to mind. Yet, as suggested by the preceding iconic poster, Buddhism’s connection to calamities in Japan has a long history, beginning with its introduction to the country in the sixth century. In fact, Buddhism owes its very existence in Japan to the early belief that it had the power to protect the country from various calamities, whether natural or human. Buddhism’s role in this regard has long been encapsulated in the title “nation-protecting Buddhism” (gokoku bukkyo).

Needless to say, Buddhism’s ability to protect the nation was severely tested, if not effectively destroyed, by Japan’s defeat in the Asia-Pacific War. That is to say, this defeat occurred despite the fervent rituals and prayers for Japan’s victory conducted by Japan’s leading Buddhist clerics. Nevertheless, Buddhism has an even deeper connection to disasters, one that could not be eradicated even by defeat in war, that is, its connection to suffering and death.

Just how closely Buddhism is connected to suffering can readily be seen in Buddhism’s basic teachings as encapsulated in the Four

Buddhist priests and coffins of tsunami victims |

Noble Truths:

1. Life means suffering.

2. The origin of suffering is attachment.

3. The cessation of suffering is attainable.

4. The path to the cessation of suffering.

While Buddhism is not the pessimistic religion that some have alleged in that it does offer a way to end suffering, it nevertheless stresses that suffering, leading to death sooner or later, is inherent to the human condition. Thus, disasters, when they occur, are not seen as anything new or surprising but rather as further proof of the inevitability of suffering based on the fundamental Buddhist insight of the impermanence of all things.

Inasmuch as Buddhism enjoys a near monopoly on funeral rites in Japan it was inevitable that photographs of priests praying over the coffins of tsunami victims would quickly appear. What is unusual about the above photo, however, is that the victims are being buried without first having been cremated. This is explained by the need to quickly bury the large number of victims in an area where crematoria were no longer operating. These particular victims will later be disinterred and cremated when conditions allow.

As massive as the loss of life was due to the tsunami, it pales in comparison with the loss of life during the Asia-Pacific War. As the following photograph reveals, Buddhist priests also played a significant role in that war, that is, as Buddhist chaplains whose major role was, as now, to oversee the cremation (when feasible) and burial of the dead.

Buddhist military chaplain |

Unlike US military chaplains, Buddhist chaplains did not wear military uniforms, but their military boots and pith helmets made it clear that they, too, were part of Japan’s military effort. Many commanders found it comforting to have their unit’s Buddhist chaplain accompany them on periodic tours of the front lines based on the belief that the priest’s allegedly miraculous powers would insure their safety.

Nevertheless, behind all Buddhist chaplains’ “practical work” on the battlefield lay a metaphysics that promoted a value that became increasingly important the longer the war lasted – resignation to one’s death. Buddhism was seen as providing the quickest route to acquiring the needed resignation, for it was Buddhism that taught living means to suffer since neither human nature nor the world we live in are perfect. During our lifetime, we inevitably endure physical suffering such as pain, sickness, injury, old age, weakness, and eventually death; and we have to endure such psychological suffering as sadness, fear, frustration, disappointment, and depression. Thus, life in its totality is imperfect and incomplete because our world is subject to impermanence. Since we are never able to keep permanently what we strive for, we must accept that we ourselves as well as all we hold dear will inevitably pass away.

Kamikaze pilot covered in cherry blossoms |

Once this metaphysical foundation has been grasped we can better understand the suicidal, if tactically meaningless, “banzai” charges that characterized the latter stages of the war. This includes, of course, the suicidal attacks of so-called kamikaze pilots. One Sōtō Zen scholar glorified these pilots as follows: “The source of the spirit of the Special Attack Forces [i.e., kamikaze] lies in the denial of the individual self and the rebirth of the soul, which takes upon itself the burden of history. From ancient times Zen has described this conversion of mind as the achievement of complete enlightenment.”1

In Japanese culture, of course, it is the fragile and short-lived cherry blossom that best embodies the idea of impermanence. Thus, as shown in the following picture, the cherry blossom quickly became associated with those youth called upon to sacrifice their lives in a desperate attempt to avert defeat.

And, as the following cherry blossom-decorated photo shows, Japan’s rocket-propelled, bomber-launched, suicide plane was also called Ōka (Cherry Blossom).

If these photos seem far removed from recent events, it is worth recalling the photos of workers in the early days of the Fukushima accident headed into the dark and dangerous nuclear reactor buildings. Japanese commentators appropriately referred to such laborers as possessed of the same kamikaze spirit: “At Fukushima, a core of several hundred workers essentially sacrificed themselves in the early stages of the disaster…‘I don’t know of any other way to say it, but this is like suicide fighters in a war,’ said University of Tokyo radiology professor Keiichi Nakaga.”2

Cause of Suffering

Ōka plane |

In Buddhism the cause of suffering is seen as stemming from attachment, that is, attachment to transient things and the ignorance thereof. Transient things not only include the physical objects that surround us, but also ideas, and in a greater sense, all objects of our perception. Ignorance is the lack of understanding of how our mind is attached to impermanent things. The reasons for suffering are desire, passion, ardor, pursuit of wealth and prestige, striving for fame and popularity, or in short: craving and clinging. Because the objects of our attachment are transient, their loss is inevitable, thus suffering will necessarily follow. Objects of attachment also include the idea of a “self” that is a delusion, because there is no abiding self. What we call “self” is just an imagined entity, and we are merely a part of the ceaseless becoming of the universe.

Worker in the early days of the Fukushima accident |

In the years since the advent of the Heisei period (1989), Japan has experienced numerous crises, ranging from political, financial, and social turmoil to natural disasters, as if inheriting the turbulence of the previous eventful and painful Showa history (1926-89). In the face of calamity, however, the Japanese people have always impressed the world with their extreme resilience and what is often referred to as their “stoicism.” It has been generally suggested that the Japanese people are impressively responsive to disasters, given their all too frequent experience of calamity in an island country located on the Pacific “rim of fire.”

Stoicism, however, is an ancient Greek school of philosophy founded at Athens by Zeno of Citium. The school taught that virtue, the highest good, is based on knowledge, and that the wise live in harmony with divine Reason (also identified with Fate and Providence) that governs nature, and are indifferent to the vicissitudes of fortune and to pleasure and pain.

Buddhism, on the other hand, does not teach indifference to the vicissitudes of life but rather recognition of them as an integral part of the very fabric of an all too impermanent existence. Thus, while suffering remains real, at least to the degree one remains attached to the world, the bitter sting of impermanence is nevertheless alleviated to some degree by the realization of its inevitability. Thus, rather than stoics, the Japanese may best be characterized as simply “realists.”

This may also help to explain, at least in part, why the Japanese, by and large, do not seem as susceptible as many others to what psychologists have called the “normalcy bias.” The normalcy bias refers to a mental state that people enter when facing a disaster resulting in underestimation of both the possibility of a disaster occurring as well as its possible effects. This often results in situations where people fail to adequately prepare for a disaster, and, on a larger scale, the failure of governments to include the populace in their disaster preparations. The assumption is made that since a disaster never occurred in the past, then it will not occur in the future. It also results in the inability of people to cope with a disaster once it does occur. While there is clearly room to criticize the Japanese government for its past and present lack of disaster preparedness, the Japanese people as a whole do respond with admirable calm and discipline.

If being a “realist” and overcoming the “normalcy bias” may be viewed as positive traits, it is also true that the Japanese have often been identified as having a “stoic attitude” based on their embrace of gaman, or in its verb form gaman suru. Interestingly, this term has deep Buddhist roots in that it is derived from the Sanskrit word māna, (conceit). In its original Buddhist meaning this term had a clearly negative meaning in that it designated one of seven types of human conceit, that is, attachment to self (ga). Yet following the onset of the Edo period in 1600 the fact that “self-attachment” was such an enduring human characteristic led to its negative Buddhist meaning being replaced with a positive meaning in which gaman suru now refers to the ability to endure adversity no matter how severe. In fact, gaman is today often regarded as one of the quintessential Japanese virtues or unique national characteristics. The question must be raised, however, as to what was lost by this medieval change from its original Buddhist meaning, especially when gaman can and has been used to justify the endurance of human-created injustice, including exposure to nuclear radiation?

Yet another popular Japanese term stemming from Buddhism is hōben (Skt. upāya) or “skillful means.” The skillful means referred to here is the Buddha’s ability to adjust his message, that is, the teaching of the Dharma, to meet the spiritual needs and understanding of his listeners. Any such adjustment, however, must be guided by both wisdom and compassion. Nevertheless, over the centuries another meaning of upāya has emerged, a meaning best translated as “expedient means.” Thus, what is “expedient” for the speaker becomes an acceptable expression of the truth. This latter meaning is best captured by the Japanese phrase uso mo hōben (a lie is also expedient means). In a recent article in The Japan Times, the naturalized Japanese Debito Arudou pointed out that the widespread acceptance of this phrase has led to a general attitude in Japan of tolerating, even justifying, not telling the truth, at least the whole truth. Needless to say, nowhere has this tolerance been more evident than in the Japanese government’s continued obfuscation of the seriousness of events linked to Fukushima, most especially the ongoing and widespread radiation contamination. Arudou writes:

Post-Fukushima Japan must realize that public acceptance of lying got us into this radioactive mess in the first place. For radiation has no media cycle. It lingers and poisons the land and food chain. Statistics may be obfuscated or suppressed as usual. But radiation’s half-life is longer than the typical attention span or sustainable degree of public outrage. As the public — possibly worldwide — sickens over time, the truth will leak out.3

How ironic that it took a naturalized Japanese of Western origin to point out just how twisted the popular Japanese understanding of a key Buddhist doctrine has become.

Similarities and Differences with World War II

On August 28, 1945, shortly after Japan’s surrender, Prime Minister Higashikuni declared: “The military, civilian officials, and the people as a whole must thoroughly self-reflect and repent. I believe that the collective repentance of the hundred million (ichioku sōzange) is the first step in the resurrection of our country, the first step in bringing unity to our country.”4

By employing the Buddhist term zange (repentance), Higashikuni effectively shielded Japan’s political and military leaders, including the emperor, from any criticism or responsibility for Japan’s disastrous defeat. However, as revealed in the following “Verse of Repentance” (Zangemon), Buddhist repentance refers to a personal acknowledgement of moral imperfection.

The various evil deeds that I have done in the past, all stem from beginningless greed, hatred and delusion. These deeds were born from body, speech and mind, and I now repent them all.5

Higashikuni cleverly invoked Buddhist repentance to socialize, and thereby excuse, the political recklessness if not criminality of Japan’s wartime political and military leaders, thereby making each and every Japanese personally responsible for the disaster visited on the Japanese people as well as Asian victims of Japanese aggression.

Further, Higashikuni’s approach was echoed by related sentiments on the part of Japan’s leading Buddhists. Sōtō Zen scholar-priest Masanaga Reiho, for example, stated on September 15, 1945:

The cause of Japan’s defeat . . . was that within our country there were not sufficient capable men who could direct the war by truly giving it their all… That is to say, we lacked individuals who, having transcended self-interest, were able to employ the power of a life based on moral principles…It is religion and education that have the responsibility to develop such individuals.6

The question is, did something similar occur during the recent disaster? The answer, as many readers already know, was that it did, as seen in the words of Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintaro. On March 14, 2011 Ishihara held a press conference at which he stated:

The identity of the Japanese people is greed. This tsunami represents a good opportunity to cleanse this greed (gayoku), and one that we must avail ourselves of. Indeed, I think this is divine punishment…though I do feel sorry for the disaster victims.7

In making this claim, it should be noted that Ishihara was following a well-established Buddhist precedent in Japan, one that be traced back at least as far as priest Nichiren in the thirteenth century. In 1260, with Japan facing a series of calamities at home and the threat of Mongol invasion from abroad, Nichiren submitted his famous Risshō-ankoku-ron (Treatise on Pacifying the Country through the Establishment of True [Buddhism]) to Japan’s warrior rulers in Kamakura. The first dialogue contained the following passage:

The people of today all turn their backs upon what is right; they give their allegiance to evil. That is the reason why the benevolent deities have abandoned the nation, why sages leave and do not return, and in their stead come devils and demons, disasters and calamities that arise one after another.

This viewpoint was similarly invoked during the Asia-Pacific War as an expression of karmic recompense.

There is not so much as a single bullet flying from the enemy that happens by chance. It is definitely the work of karma, for it is karma that makes it strike home…Your husband died because of his karma…It was the inevitability of karma that caused your husband’s death. In other words, your husband was only meant to live for as long as he did. In those bereaved that have recovered their composure, one sees the realization that their husband’s death was due to the consistent working of karma. No one was to blame [for his death] nor was anyone in the wrong. No one bears responsibility for what happened, for it was simply his karma to die.8

Despite these clear precedents, however, this time Ishihara’s attempt to blame the victims for their victimization created such an uproar that he was forced to apologize. Thus, on the following day, March 15th, the Governor held a second press conference at which he retracted his remarks and offered “a deep apology” for having made them.9

Commenting on Ishihara’s remarks, John Nelson, chairman of theology and religious studies at the University of San Francisco, noted that his remarks about divine retribution stemmed from ancient Japanese Buddhist ideas that have now become unpopular.10

While ancient Japanese did embrace an understanding of karma exemplified by Ishihara’s remarks, it should be noted that such views were not those of Buddhist doctrine. On the contrary, according to Buddhist doctrine, karma refers to only the first of five rules or processes that cause effects. The five rules are: 1) The positive or negative moral consequences of one’s actions; 2) Laws of nature; 3) Seasonal changes and climate; 4) Genetic inheritance; and 5) Processes of consciousness. Thus it is clearly mistaken, though popular, to claim that natural events like earthquakes, tsunami, etc. are the result of human moral failures, that is, their karma. Nevertheless, in Japanese Buddhism this mistaken understanding of karma has long been employed to place blame on the victims of misfortune, including social injustice.

In truth, something similar can be said of at least some representatives of the world’s major religions. In Christianity, for example, Rev Gerhard Wagner, 54, was quoted in his local parish newsletter as saying that the death and destruction of Hurricane Katrina was “divine retribution” for New Orleans’ tolerance of homosexuals and laid-back sexual attitudes. Subsequent to his remarks, the Vatican made this Roman Catholic Austrian cleric a bishop.11

In Israel, Shas spiritual leader and former Chief Sephardic Rabbi Ovadia Yosef described Hurricane Katrina as punishment meted out by God as a result of US President George W. Bush’s support for the Gaza and northern West Bank disengagement. Nor was that all. “There was a tsunami and there are terrible natural disasters, because there isn’t enough Torah study… black people reside there (in New Orleans). Blacks will study the Torah? (God said) let’s bring a tsunami and drown them,” the Rabbi said.12 Clearly the cause of disasters of whatever kind remains a controversial topic among the world’s religions.

War Victims as “Polluted”

Yet another ancient religious belief in Japan is that disaster victims become “polluted” by their experience. While the idea of ritual pollution originally comes from Shinto, it has become firmly entrenched in the Buddhist-Shinto syncretism so typical of today’s Japan. Referencing the aftermath of the Asia-Pacific War, John Dower noted:

Despite a mild Buddhist tradition of care for the weak and infirm…whole new categories of “improper” people felt the sting of stigmatization. These included the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with their taint of – really, their pollution by – radiation; war orphans and street children…War widows …And homeless ex-servicemen or any of the other abandoned people who clogged public places such as Tokyo’s Ueno Station.13

As the following photo only too graphically reveals, pollution due to radiation exposure has once again become the focus of the public’s attention.

Child undergoing a radiation check |

The April 3, 2011 edition of Newsweek described the current situation in Japan as follows:

People living near the damaged reactor have already begun to face discrimination. They have been barred from staying in inns outside Fukushima prefecture. Angry motorists in Tokyo and other cities have complained that Fukushima-plate-bearing cars were “contaminated.” Some Minamisoma citizens have sought treatment at medical clinics in cities beyond the buffer zone, only to be turned away because they didn’t have “radiation-free” certificates…children evacuated from Fukushima prefecture—especially from the exclusion and buffer zones—and sent to centers in Tokyo and other cities were now being singled out for rough treatment in elementary schools. Their classmates were shunning them and taunting them as being “irradiated”…As Japan reckons with its latest nuclear tragedy, the suffering endured by the hibakushas still weighs heavy on the land.

Final Comments

As the foregoing comments make clear, the distance between the Asia-Pacific War and the still unfolding events precipitated by the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011 is typically much less understood. The same can be said for Buddhism’s relationship between the two. It is not difficult to envision that as victims of Japan’s ongoing radiation contamination contract such illnesses as cancer, and die, that Buddhist priests will once again conduct their funerals and memorial services, understanding their demise as but another manifestation of impermanence. Yet Buddhism also has a strong commitment to compassion based on the realization of the ultimate identity of all things. One is left to ponder what practical impact, beyond conducting funerals, this commitment will have on the lives of the victims of the world’s largest industrial accident. Given Buddhism’s long history in Japan of blaming victims for their misfortune, one cannot be too sanguine about the future.

That said, it is noteworthy that there are a handful of Buddhist priests like Zen-affiliated Abe Koyu, abbot of Joenji temple in Fukushima city. In addition to offering prayers for the thousands left dead or missing from the multiple disasters, he has undertaken the additional task of searching out radioactive “hot spots” in the Fukushima city area and cleaning them up, storing the irradiated earth on the grounds of his own temple. Further, in the summer of 2011 Abe grew and distributed sunflowers and other plants, such as field mustard and amaranthus, in an effort to lighten the impact of the radiation and cheer local residents. Abe explained that he and the other monks are storing the soil on a hill behind the temple because neither the government nor the nuclear plant operator Tokyo Electric Power (TEPCO) are helping with the clean-up. “No-one else would take the soil. If there’s nobody to take care of it, the decontamination can’t get going because there’s nowhere to get rid of it,” Abe said. (“Japan Priest Fights Invisible Demon: Radiation,” available here.)

On the other hand, as Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko’s recent speech to foreign journalists revealed, the Japanese government has reverted to its timeworn stance of asserting that, as far as the Fukushima nuclear accident is concerned, all of the major players share responsibility. “Rather than blaming any individual person I believe everyone has to share the pain of responsibility and learn this lesson,” Noda claimed. (f.n. “Noda says no individual to blame for Fukushima nuclear crisis,” available here.) This stance means, of course, that no one need fear criminal prosecution for what is now widely recognized as the world’s greatest industrial accident to date. However, perhaps it should be considered ‘progress’ that Noda didn’t go on to assert the entire Japanese people bore responsibility for what happened.

In any event, given continued evasive comments like Noda’s, it would be well for all, Buddhist and non-Buddhist alike, to ponder the following words of Helen Caldicott, the Australian authority on the effects of nuclear radiation:

The early nuclear physicists in the Manhattan Project recognize[d] the toxicity of radioactive elements. I knew many of them quite well. They had hoped that peaceful nuclear energy would absolve their guilt over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but it has only extended it.14

Brian Daizen Victoria holds an M.A. in Buddhist Studies from Sōtō Zen sect-affiliated Komazawa University in Tokyo, and a Ph.D. from the Department of Religious Studies at Temple University. In addition to a 2nd, enlarged edition of Zen At War (Rowman & Littlefield), major writings include Zen War Stories (RoutledgeCurzon); an autobiographical work in Japanese entitled Gaijin de ari, Zen bozu de ari (As a Foreigner, As a Zen Priest); Zen Master Dōgen, coauthored with Prof. Yokoi Yūhō of Aichi-gakuin University (Weatherhill); and a translation of The Zen Life by Sato Koji (Weatherhill). He is professor of Japanese Studies and director of the AEA “Japan and Its Buddhist Traditions Program” at Antioch University in Yellow Springs, Ohio.

Recommended citation: Brian Victoria, ‘Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 11, No 7, March 12, 2012.

Responding to Disaster: Japan’s 3.11 Catastrophe in Historical Perspective

Is a Special Issue of The Asia-Pacific Journal edited by Yau Shuk-ting, Kinnia

See the following articles:

• Yau Shuk-ting, Kinnia, Introduction

• Matthew Penney, Nuclear Nationalism and Fukushima

• Susan Napier, The Anime Director, the Fantasy Girl and the Very Real Tsunami

• Yau Shuk Ting, Kinnia, Therapy for Depression: Social Meaning of Japanese Melodrama in the Heisei Era

• Timothy S. George, Fukushima in Light of Minamata

• Shi-Lin Loh, Beyond Peace: Pluralizing Japan’s Nuclear History

• Brian Victoria, Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima

See the complete list of APJ resources on the 3.11 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear power meltdown, and the state and societal responses to it here.

1 Quoted in Brian Victoria, Zen at War, 2nd edition, p. 139. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006).

2 Harvey Wasserman, “Fukushima and the Radioactive Sea,”Counterpunch, May 26, 2011. link.

3 “The costly fallout of tatemae and Japan’s culture of deceit,” The Japan Times, November 1, 2011. link.

4 Quoted in John Dower, Embracing Defeat, 2000, p. 496. (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2000).

5 Found in “The Practices & Vows of Samantabadra Bodhisattva,” Avatamsaka Sutra, Chapter 40.

6 Quoted in Victoria, op cit, p. 160.

7 “‘Daishinsai wa tenbatsu’ ‘Tsunami de gayoku arai otose’ Ishihara tochiji,”Asahi Shimbun, March 14, 2011. Available here.

8 Quoted in Brian Victoria, Zen War Stories, Routledge, 2003, p. 159.

9 Justin McCurry, “Tokyo governor apologizes for calling tsunami ‘divine punishment,” The Guardian, March 15, 2011. Available here.

10 “Tokyo Governor Apologizes for Calling Disasters Divine Punishment,” Global News (@Sizly.com). Available here.

(Accessed on November 11, 2011)

11 Nick Pisa, “Cleric who said Hurricane Katrina was God’s punishment for how homosexuality is made bishop by Vatican,” Mail Online, February 2, 2009. Available here. Due to the controversy surrounding his views, the Pope effectively revoked Wagner’s appointment a month later.

12 Zvi Alush, “Rabbi: Hurricane punishment for pullout,” ynetnews.com, July 5, 2009. Available here.

13 Dower, op cit, p. 61.

14 “Unsafe at Any Dose,” New York Times, April 30, 2011. Available here.