The Middle East Revolutions in Historical Perspective: Egypt, Occupied Palestine, and the United States

Herbert P. Bix

From the early 1880s down to the end of World War II, British and French colonial rulers, among others, held the Arab peoples of the Middle East in subjugation. Weakened by the war against Hitlerism, the European imperialists retreated under pressure from the United States, which stepped in to take their place. The creation of Israel as the last “colonial-settler state” (1948) and Israel’s expulsion of the indigenous population of Palestine from their land and homes framed one side of the European retreat; the failed Anglo-French invasion of Egypt, known as the Suez Canal crisis (1956), framed the other.

During World War II, the U.S. moved decisively to secure the oil fields of Saudi Arabia and transfer the desert kingdom from the British sphere of influence to one of hegemony by the U.S. and American oil corporations. President Franklin D. Roosevelt entered into a collaboration with the reactionary King Ibn Saud–a “lethal embrace” that his successors, Truman and Eisenhower but also Johnson and Nixon, steadily developed.1 Through the machinations of the CIA, Iran and the oil-producing countries in the Persian Gulf region came under Washington’s protection.

|

King Saud and Roosevelt, 1945 |

Thereafter, the overall framework for Middle East order that American policy planners constructed was essentially a continuation of the European one, based on support for monarchs, military dictators, and Saudi Islamist extremism. Israel fit into the picture because Pentagon officials considered it a possible base from which to project U.S. power throughout the region–a prospect that Saudi Arabia found unobjectionable. In 1967, when the U.S.-Israel relationship was first established in its present form, Washington’s commitment to Israel went hand-in-hand with its hostility to the secular nationalism of Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Now a spontaneous democratic revolution is in progress in modern Egypt. The army and police-centered political power, to save itself from the threat of democracy, has forced President Hosni Mubarak, who ruled with unstinting U.S. support for thirty years, to transfer power to the army and exit the scene. The army leadership, while appearing to engage the democratic movement, is fighting to control the pace and content of reform. Egypt with 82 million people is the largest Arab state and one of the most strategically important, besides being a cultural leader of the Arab world. The system of economic exploitation and private plunder that military dictators Anwar Sadat and Mubarak operated for the past forty-years is deeply rooted. Popular forces that would significantly disentangle the armed forces from the economy–in effect dismantle the social basis of the dictatorship–are being subtly resisted by Egypt’s military rulers and privileged elites. They have not abdicated as they should, but instead merely promised to allow “an elected civilian government to . . . build a free democratic state,” while at present ruling by military fiat.2 This persistence of military rule is the first structural obstacle that Egypt’s oppressed people face as they struggle to move their peaceful revolution forward.

|

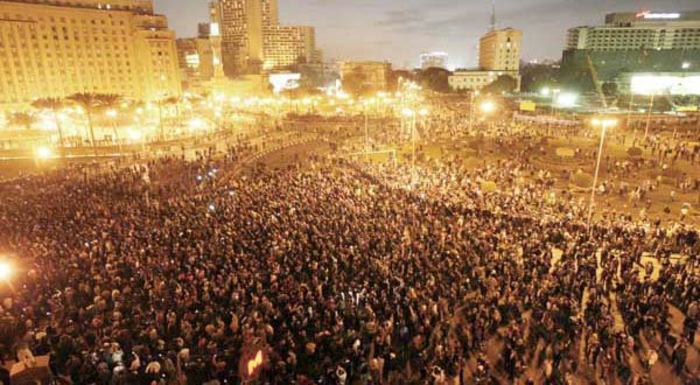

Tahrir Square |

The second arises from the deceptive U.S. response to the popular revolutions triggered by the political awakening in Tunisia that then spread to Egypt and Yemen, where protests are continuing. Since Mubarak’s fall, over 10,000 protestors have called for freedom and reform in the face of state violence in the tiny, oil-rich state of Bahrain, where the U.S. Fifth Fleet is based, and anti-clerical protests have re-ignited in Iran. Earlier, sympathy demonstrations erupted in Saudi Arabia, Jordan and the Israeli-occupied West Bank. Youthful protestors have taken to the streets and are calling for Egyptian-like reform in Algeria, which borders Tunisia. Algeria’s dictatorship also lacks legitimacy and for years has been beset by armed opponents.3 Taken together, the moving firestorm of revolutionary democratic protests that frighten dictators and monarchs has affected the entire American structure of Middle East domination and, indeed, U.S. relations with Muslim peoples across Asia.

In the event that the protestors in Egypt do not demobilize, that Egyptian civic organizations of a secular, democratic nature proliferate, and that they continue to influence the political process, ordinary Egyptian citizens can be expected to demand that their state authorities start pursuing an independent, pro-Egypt foreign policy consonant with Egyptian and Arab interests, which implies supporting the interests of the Palestinian people under Israel’s occupation. Although, as it became clear that Mubarak was doomed, the managers of the American national security state suddenly professed support for a less suffocating status quo for the Egyptian people–“Mubarakism without Mubarak”–they are unlikely to accept a sequence of changes that directly challenge American power and regional security priorities.

Economic misery, skyrocketing food prices and high youth unemployment, produced in part by decades of neo-liberal globalization policies, made Egypt’s protests particularly volatile. Harsh political repression intensified the force of the economic violence produced by a neo-globalization that drew in foreign capital from around the word while leaving the majority of Egyptians impoverished. This set the stage for a revolution in which Egyptian women and men, working in the new factories built during the 1990s, continued their leading role in strikes and protests that have been erupting for decades but crescendoed in recent months.

The revolutionary upsurge can also be traced to the reactions of Egyptians to the American-led invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003; the Israeli-U.S. war against Lebanon in 2006 and Hezbollah’s successful armed resistance to it; continued Israeli expansionism in East Jerusalem and the West Bank; and Israel’s blockade, with Egyptian support, of the Gazan Palestinians since 2007. The massive war crimes that Israel, with U.S. support, has perpetrated against Palestinians living in Gaza did not go unnoticed in the Arab countries. These background events not only keep the entire region in turmoil; they also make clear that critical factors in the outcome of the democratic movement will hinge on the willingness of the Egyptian officer class and its U.S. backers to share power with the emerging democratic forces.4 They must modify fundamental domestic and international policies.

Arab historian and activist Gilbert Achcar recently pointed to a vast array of Egyptian groups spearheading the opposition to the military-police dictatorship, led by Mubarak. They included: people who demonstrated solidarity with the second Palestinian uprising of 2000, and later opposed the U.S. assault and occupation of Iraq; leaders of Egypt’s free (non-government sanctioned) labor movement; associations of urban youth movements; members of the middle class, leaders of civil society movements like “Kefaya [Enough!]” and the liberal Mohamed ElBaradei, as well as representatives of the once banned Muslim Brotherhood. The Brotherhood, the largest opposition group, has evolved over many decades into a non-radical, non-clerical organization composed primarily of doctors, engineers, and other professionals for whom civil society concerns are paramount and religious ones appear to be secondary to civil society ones. Not surprisingly, Brotherhood leaders have signaled support for the army’s leadership, as has El Baradei.

Many of these leading players understand that the armed forces have long acted behind the scenes as a force for their oppression though some continue to harbor illusions about the neutrality of the national army. Mubarak’s officers and the businessmen he enriched with U.S.-funded patronage still seek to exploit those popular illusions so as to weaken the protestors.5

Reviewing schematically what has occurred, we see that during the first week of the nationwide democratic upsurge–January 25 to February 4–the protests for democracy were so powerful that some anticipated that the force of the people would quickly sweep away the dictator. The demonstrators converged on public squares throughout Egypt, in peaceful, orderly protests, demanding an end to military dictatorship and the implementation of universal principles of freedom, democracy, and economic and social justice. Gradually their demands became more specific: immediate end to the “state of emergency,” the writing of a new democratic constitution, an end to torture and police repression, reform of the corrupt judiciary, and punishment for all who committed crimes against the people. Above all, they called for the resignation of Mubarak and his entire military government, dissolution of his one-party (NDP) parliament, and the writing of an entirely new constitution. Unless all officials who formed the dictatorship resigned, and their structure of rule was dismantled, many protestors believed their sacrifices would have been in vain and they would have to live in fear of eventually being targeted for arrest and torture. Their fear dissipated, however, as their numbers swelled and confidence grew.

Until the very end, when it was a choice of Mubarak or themselves, and their American advisers had helped them to see just why Mubarak had to go, the top leaders of the National Army refused to break with him.

As the situation unfolded, senior commanders refrained from ordering soldiers to fire on citizens and offered protestors protection at some moments while encouraging them to dismantle their barricades and go home at others. On the uprising’s 9th day, after police had failed to crush the demonstrators, Mubarak’s intelligence service gathered a small army of armed thugs and had them bused into Cairo, where they converged on Tahrir Square, “epicenter” of the national revolt. Agents provocateurs, plain-clothes riot police, unemployed people whom the regime paid 17 dollars a day, thugs mounted on horseback and camels, attacked the pro-democracy protestors with fists, clubs, knives, long iron bars, Molotov cocktails, U.S.-supplied tear gas grenades, guns, and bullets.

The assault on the peaceful protestors occurred after Obama had reportedly pressed Mubarak to resign and allow his newly appointed vice president and “torturer-in-chief,” Gen. Omar Suleiman, to put down the revolt. Suleiman, trained by the U.S. military, had been the CIA’s Cairo “point man,” in charge of expediting the illegal U.S. program of extreme rendition, in which prisoners were sent to Egypt (among other countries) to be tortured.6 Journalist Pepe Escobar writes that Egyptian protestors “from all walks of life, from students to lawyers, not to mention Egyptian human-rights groups” know that Suleiman ”supervised US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) renditions as well as torture of al-Qaeda suspects). . . [and] was a minister without portfolio and director of the Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate, the national intelligence agency, from 1993 to 2011.” But it “doesn’t matter that the Egyptian street abhors him; for the top echelons of the army he is the new rais. Al-Jazeera describes him as ‘the point man’ for Egypt’s secret relations with Israel. . . . On the other side of the spectrum, Human Rights Watch stresses, “Egyptians… see Suleiman as Mubarak II, especially after the lengthy interview he gave to state television Feb 3 in which he accused the Tahrir demonstrators of implementing foreign agendas. He did not even bother to veil his threats of retaliation against protesters.”7

|

Mubarak (left) and Suleiman |

Suleiman allowed military police to attack journalists and human rights workers and bears responsibility for the deaths of over 300 demonstrators and the imprisonment and disappearances of unknown thousands. When he took over from Mubarak, Sec. of State Hilary Clinton and Frank Wisner, Jr. her special envoy to Cairo, initially let it be known that Washington supports Mubarak. Finally, on the 18th day of protests, after workers had staged strikes throughout the country and millions of Egyptians had called for the end of the regime, Mubarak stepped down. This opened the present interlude of freedom and negotiation while still leaving the military in charge and the foundation of military rule intact.

The military has normalized its central role in Egyptian politics much as Japan’s armed forces did after the Russo-Japanese War ended in 1905. Getting rid of Suleiman and his ilk and ending Egyptian military rule will not be easy. As Middle East correspondent Anthony Shadid pointed out, “Since the revolt the military has . . . emerg[ed] as the pivotal player in politics it long sought to manage behind the scenes. The beneficiary of nearly $40 billion in American aid during Mr. Mubarak’s rule, its interests span the gamut of economic life — from the military industry to businesses like road and housing construction, consumer goods and resort management. Even leading opposition leaders, like Mohamed ElBaradei, have acknowledged that the military will have a key role in a transition.”8

The 74-year-old Suleiman and 75-year-old Defense Minister, Field Marshall Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, who heads the Higher Military Council that controls the government, have conceded to the protestors demand for dissolution of the parliament and suspension of the constitution. But as they struggle to retain the military’s grip, they enjoy the backing of the U.S., Israel, and Saudi Arabia–as well as leading European powers–Britain, Germany, France, and Italy. All of them are searching for safe ways to suppress the revolution and turn Egypt’s crisis to their advantage. Because U.S. taxpayers annually provide $1.3 billion in military aid to Egypt, second only to Israel, these top Egyptian generals remain in close contact with the Pentagon and members of Congress, as well as powerful lobbyists who profit from doing business with their regime. They also enjoy the support of pro-Zionists in all branches of the U.S. government as well as right-wing pundits who back Obama’s approach to shaping the Egyptian movement so that it remains responsive to U.S. priorities.

Whither Egypt?

A brief comparison of Egypt and South Korea, societies with entirely different political cultures, reveals both the obstacles to and possibilities for democratic transitions. In these nations the U.S. fostered military dictatorships that stifled democratic forces. It did so, contrary to the conventional view, for reasons largely unrelated to shutting out Soviet influence. Washington’s main goal was to insure that each secured its place within a U.S.-dominated global neo-liberal order. Although today South Korea has 48 million citizens. little more than half the population of Egypt, and the two nations operate in dissimilar international environments, the comparison is fruitful, for it suggests that the struggle ahead for the Egyptian people, though difficult, may be more achievable, especially now that American military power is weakened by fighting simultaneous costly wars.

Under Syngman Rhee (1948-60), South Korea lacked a strong independent indigenous capitalist class and allowed few civil freedoms. Under Gen. Park Chung Hee (1961-79), Seoul provided the largest complement of mercenary troops to support the U.S. war in Vietnam. No less important, starting in the Park years South Korea experienced rapid, export-led industrialization and undertook major political and economic reforms. Its capitalist and financial class grew large and autonomous despite being hampered by the heavy weight of the military. (In 2010 South Korea had 653,000 active forces and 3.2 million regular reserves, far larger than Egypt’s military.9) Korean capitalists too benefited from the dual economic assistance of Washington and Tokyo.

|

Park and John F. Kennedy |

Following Park’s assassination, Gen. Chun Doo Hwan seized power with strong American military and diplomatic backing. In May 1980 with strong American backing, he ordered the army in Gwangju city to massacre protestors who were demanding higher wages and democratization. Chun, who enjoyed the support of President Ronald Reagan, was to be the south’s last military dictator. Student-led pro-democracy forces overthrew him in 1987. Following Chun’s fall, Korea’s democratization movement deepened, thanks in part to the ending of the cold war. Korean citizens, acting through strong labor unions and opposition parties, succeeded in exerting continuous pressure on the political process. Their actions may have influenced Taiwan’s transition from single-party military dictatorship to multi-party democracy, which began the following year. When Korean student activists merged with the urban middle class, the south, building on the economic foundations of the earlier Park and Chun dictatorships, spurted ahead economically. It deepened developmental-state policies modeled on Japan’s and became a rule-of-law state.10

The Korean transition, however, failed to ignite a regional revolutionary conflagration on the scale of the widespread democracy movements that are presently sweeping the Middle East. As the 1990s unfolded and economic power came to be concentrated in about thirty giant conglomerates (chaebol), governments in Seoul adopted more neo-liberal policies. Income inequalities deepened and legislative restrictions were imposed on unions.

South Korea, with its large middle class shows that “in normal times” procedural, multi-party “democracy” and free elections are compatible with extreme economic exploitation and anti-people domestic policies. Nonetheless, it remains economically dynamic, capable of developing its still shallow institutions of procedural constitutional democracy. Its democratic revolution stalled largely because of the continuing uncompleted civil war with the North and because it continues to play a subordinate buffer role for the U.S. with nearby North Korea, China, and Russia. Unable to end the American military presence in the form of bases and troops, it is compelled, like other nations with U.S. military bases, to accept an unequal “status of forces” agreement with Washington. Yet the combination of U.S. military overextension, and China’s rise as the world’s second economic superpower, suggest the possibility of balancing U.S. in northeast Asia, thus giving the leaders in Seoul room for maneuver.

Egypt, by contrast, occupies a place in the international order that allows less freedom of maneuver. It has never been a developmental state or one in which the rule of law gained much traction. Its armed forces are large but its intelligence and police forces are even bigger. According to a recent study, the Ministry of Interior commanded 1.7 million men in 2009, including 850,000 police and staff, 450,000 security troops, 400,000 secret police, and plainclothes auxiliaries.11 It also operates a network of prisons highly valued by the CIA. Egypt’s armed forces participate in all areas of the economy. They rein in Egyptian businessmen and foster a corrupt crony capitalism. Finally, one of the functions of the Egyptian military as a U.S. client is that it maintains peace with Israel and accommodates an expansive Zionism. Whether peace continues, no democratic government that emerges in Cairo will want to give Israel a “free hand” in the region as Sadat and Mubarak did. Rather than allow Israel to enjoy impunity, it will seek to avoid another war while renegotiating Egypt’s unequal 1979 peace treaty with Israel and ending support for Gaza’s blockade.12

Meanwhile the future of an Egyptian democratic transition remains in the balance. The army has taken power and continues to rule by emergency decree, but strikes continue, as they must, and the overall situation remains unstable. The astonishing, courageous revolutionary movement so far has not suffered any violent setback; but neither has it proposed anything beyond a democratic political authority and a new constitutionalizing of “democracy,” which could mean the eventual suppression of strikes and labor unions that have energized the revolution. Egypt’s youthful democratic leaders, recently united in a Council of Trustees,must overcome the triple legacies of military domination, extreme poverty, and subordination to U.S. and Israeli policies. They can do that by not losing sight of the fact that democracy is, as Noam Chomsky astutely observed, process, not goal.

Feb. 15, 2011

My thanks to Noam Chomsky, James Petras and Mark Selden for information, perspective and editorial suggestions.

Herbert Bix, author of Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, which won the Pulitzer Prize, teaches at Binghamton University and writes on issues of war and empire. He is a Japan Focus associate.

Recommended citation: Herbert P. Bix, The Middle East Revolutions in Historical Perspective: Egypt, the Palestinians, and the United States, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 8 No 1, February 21, 2011.

Notes

1 Michael Klare, Blood and oil: The Dangers and Consequences of America’s Growing Petroleum Dependency (Metro politan Books, 2004), pp. 26-55; Alfred E. Eckes, Jr. and Thomas W. Zeiler, Globalization and the American Century (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003), pp. 114-5.

2 Chris McGreal, “Army and protestors disagree over Egypt’s path to democracy,” posted Feb. 12, 2011, at guardian.co.uk.

3 Michael Slackman and J. David Goodman, “Unrest Grows in Bahrain as Police Kill a 2nd Protestor,” New York Times, Feb. 15, 2011.

4 Martin Chukov, “Algerian protestors clash with police as Egypt fervour spreads,” posted Feb. 12, 2011 at guardian.co.uk.

5 Hossam el-Hamalawy, “Egypt protests continue in the factories,” posted Feb. 14, 2011 at guardian.co.uk.

6 The Goldstone Report: The Legacy of the Landmark Investigation of the Gaza Conflict, with an Introduction by Naomi Klein, ed. by Adam Horowitz, Lizzy Ratner, and Philip Weiss (The Nation Books, 2011). The editors of this abridged version of the much longer report focus on the background to and the main events of the December 2008-January 2009 assault. The entire report can be found online here.

7 Gilbert Achcar interviewed by Farooq Sulehira, Socialist Project, Bulletin No 459, Feb. 7, 2011.

8 On the web: link.

9 Pepe Escobar, “’Sheik al-Torture’ is now a democrat,” posted Feb. 9, 2011, here.

10 Anthony Shadid, “Discontented Within Egypt Face Power of Old Elites,” New York Times, Feb. 4, 2011.

11 Republic of Korea armed forces statistics are taken from Wikipedia, based on official ROK sources.

12 Mikyung Chin, “Civil Society in South Korean Democratization,” in David Arase, ed., The Challenge of Change: East Asia in the New Millennium (Institute of East Asian Studies, Univ. of California, Berkeley, 2003), p. 202.

13 Clement Moore Henry and Robert Springborg, Globalization and the Politics of Development in the Middle East (Cambridge Univ. Press), p. 195.

14 Daniel Levy, “Israel’s Options After Mubarak,” Al Jazeera, posted Feb. 13, 2011 here.