Dead Forests, Dying People: Agent Orange & Chemical Warfare in Vietnam

Fred A. Wilcox

Photographs by Brendan B. Wilcox

In the abominable history of war, with the sole exception of nuclear weapons, never has such an inhuman fate ever before been reserved for the survivors.

—Dr. Ton That Tung, Vietnamese research scientist

Making their way through Vietnam’s dense jungles, U.S soldiers heard a cacophony of squawking birds, chattering monkeys, and insects buzzing like high voltage wires. But after C-123 cargo planes swooped low over the trees, saturating them with Agent Orange, the ground was littered with decaying jungle birds, paralyzed and dying monkeys. Clusters of dead fish shimmered like buttons on the surface of slow-moving streams. Years later, veterans will recall being soaked, like the trees, when aircraft jettisoned their herbicides. They will remember feeling dizzy, bleeding from the nose and mouth, suffering from debilitating skin rashes and violent headaches after being exposed to Agent Orange, an herbicide contaminated with TCDD-dioxin, a carcinogenic, fetus deforming, and quite possibly mutagenic chemical.

Vietnamese caught in the path of herbicide missions complained that they felt faint, bled from the nose and mouth, vomited, suffered from numbness in their hands and feet, and experienced migraine-like headaches. They said that farm animals grew weak, got sick, and even died after being exposed to defoliants. In late 1967, following a period of massive use of Agent Orange in Vietnam, Saigon newspapers began publishing reports on a new birth abnormality, calling it the “egg bundle-like fetus.” One paper, Dong Nai, published an article about women giving birth to stillborn fetuses, with a photograph of a dead baby whose face was that of a duck. There were accounts of babies being born with two heads, three arms and 20 fingers; babies with heads like sheep or poodles; babies with three legs. The Saigon government argued that these birth defects were caused by something called “Okinawa bacteria.” Peasants whose families had lived on the same land for generations said they’d never encountered such strange phenomena. The US dismissed these complaints as communist propaganda.

On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese tanks smashed into the grounds of the presidential palace in Saigon, ending our nation’s longest, second most expensive, and most divisive conflict since the Civil War. Approximately 58,135 Americans had been killed in action, 304,704 were wounded, and 2,231 were missing in action. More than 5 million Vietnamese were killed and wounded, leaving 131,000 war widows and 300,000 orphans.1

Angry over the outcome of the war, as though the Vietnamese had tricked the United States into invading their country and then refused to fight fairly, the U.S government imposed an embargo on trade with Vietnam, blocked private relief programs for that war-torn country, and found other ways to punish its former enemy. From 1961, when the military first began using herbicides in Vietnam, until 1970, when it suspended the use Agent Orange, chemical warfare turned Vietnam’s majestic triple-canopy jungles into toxic graveyards, and its mangrove forests into eerie moonscapes. Sooner or later, said those who knew little or nothing about the long-term effects of herbicides like Agent Orange, the trees would grow back and the tigers, bears, elephants and other creatures would return. Forty years after the last spray mission in Vietnam, the jungles have not recovered, and no one knows for certain when, if ever, they will.

In the spring of 1978, Paul Rheutershan, a twenty-eight-year old self-proclaimed “health nut” appeared on the “Today Show,” where he shocked many of the program’s viewers by announcing: “I died in Vietnam, but I didn’t even know it. As a helicopter crew chief, Paul had flown almost daily through clouds of herbicides produced by C-122 provider craft. He observed the dark swaths cut into the jungle by the spraying, watched the mangrove forests turn brown, sicken and die, but didn’t really worry about his own health. After all, the US Army had assured its troops that Agent Orange was “relatively nontoxic to humans and animals.”2

Convinced that his illness, and quite possibly that of other Vietnam veterans, was the result of their having been exposed to Agent Orange, Paul founded Agent Orange Victims International, and later filed a class action lawsuit against Dow Chemical and other wartime manufacturers of Agent Orange. On December 14, 1978, Rheutershan died from the cancer that had destroyed much of his colon, liver, and abdomen. The Veterans Administration denied then, and would continue to deny for many more years, any connection between exposure to Agent Orange and human illness.3

Responding to American veterans’ concerns about the possible health effects of Agent Orange, the Department of Defense claimed that combat troops had not entered defoliated zones until six weeks after Air force pilots had destroyed the trees. By that time, said the DOD, residue from the herbicide spray would have broken down, limiting soldiers’ exposure to toxic chemicals.

“Are you kidding me?” scoffed veterans I asked about the government’s assertions. “More like six hours. Six minutes. What were we going to do, sit back and wait for the enemy to attack us and then book back into the bush? Drank water and ate food sprayed with Agent Orange. Slept on ground soaked with that shit. Got sprayed directly. Soaking wet. The government is lying. They can make up all the stories they want but we know better. They weren’t there. We were. They’re not fooling anyone but themselves.”

In Waiting for an Army to Die: The Tragedy of Agent Orange, I wrote about Ray Clark, a combat Marine who served in Vietnam at the height of the government’s chemical warfare campaign. One morning, just a few years after he returned home, Ray found blood in his urine. Alarmed, he went straight to the Veterans Administration hospital, where doctors informed him that he was mixing ketchup and water in specimen jars. “They insisted that I was doing something to myself so I could receive disability, and the problem was all in my head,” said Clark. “They tested me for everything but bladder cancer. They gave me a brain scan, shot dye into my kidneys, announced that I was suffering from a nervous breakdown, and even tested me for epilepsy.”

At last, after many months, the VA discovered that Ray Clark was in fact suffering from bladder cancer.

Ray Clark would meet young veterans who’d been diagnosed with cancer of the colon, liver dysfunction, testicular cancer, heart ailments, veterans whose wives had suffered numerous miscarriages, and whose children were born with as many as sixteen birth defects,

“And for so long no one was willing to do studies to determine just what is causing all these problems. They’ve studied rats, mice, rabbits, chickens, and monkeys, and found that dioxin gives them cancer, causes their death, deforms and kills their offspring. But all this doesn’t apply to us… But the government doesn’t want to admit that the stuff they were spraying on people was 2,000 percent—almost twenty times—more contaminated by dioxin than the domestic 2,4,5-T that was banned in 1979 by the Environmental Protection Agency. Some of the stuff sprayed on Nam was 47,000 percent more contaminated. And they sprayed it over and over on more areas. What the government doesn’t want to admit is that it is responsible for killing its own troops.”4

From 1982, I traveled the country, interviewing scientists, lawyers, doctors, and listening to veterans who’d been insulted by staff at Veterans Administration hospitals, denied proper care, accused of being malingers, told they were trying to con money out of the government, and informed that they were alcoholics and drug addicts suffering not from serious physical illnesses, but from combat stress. When I asked veterans and their families why they thought the government was treating them with such contempt, they replied: “Because they’re just waiting for us all to die.”

That was a very long time ago. No one knows, or will ever know, how many Vietnam veterans have died lonely, bitter, and depressed from Agent Orange, knowing that the government they served cared so little about them.

At the height of the fighting, Dr. Nguyen Thi Ngoc Phuong was a young intern at Tu Du maternity hospital in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). A beautiful and remarkably cheerful woman, Dr. Phuong has dedicated her life to researching, writing, and speaking about the horrors of chemical warfare.

“I didn’t know anything about the spraying,” she says. “And nothing about Agent Orange. But one day, it was 1969, and I delivered for the first time in my life a severely deformed baby. It had no head or arms. The mother didn’t see her child, and I tried to hide my tears and my fear from her. I couldn’t bring myself to tell her what the baby looked like, so I said it was very weak. It died, and I just told her that it had been too weak to live.”

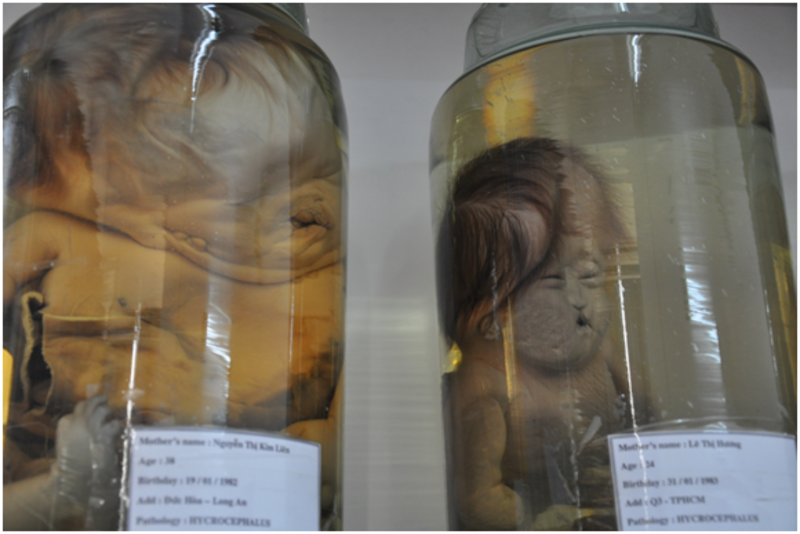

Dr. Phuong delivered more and more babies with missing limbs, two bodies fused together with one set of internal organs; babies with partial or missing brains; babies with missing heads; babies that didn’t open their eyes, didn’t cry and died within a few days after delivery. Instead of fully formed fetuses, some women at Tu Du gave birth to formless bloody lumps. Dr. Phuong attempted to tell colleagues about her growing suspicions that the birth defects she was seeing and about which she was hearing might have something to do with the U.S. military’s campaign to destroy Vietnam’s jungles and forests.

“I was very much criticized by my colleagues,” she says. “I saw the babies and I knew that sooner or later people would begin to believe me, but it took ten years until they did. I just felt the need to find out what was wrong, and I wanted to do something to help the parents and the children.”

While Dr. Phuong struggled with how to console young mothers who’d given birth to hopelessly deformed babies, scientists in the United States discovered that even in the lowest

doses given, 2,4,5-T, one of the herbicides in Agent Orange, caused cleft palates, missing and deformed eyes, cystic kidneys and enlarged livers in the offspring of laboratory animals. The results of this study were withheld until 1969, the year Dr. Phuong spared a young mother from knowing that she had given birth to a monster.

|

Dr. Phuong decided to keep hundreds of deformed fetuses in a locked room at Tu Du Hospital Boy missing hands and feet, Tu Du Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City |

“What happened in Vietnam,” says Dr. Phuong, “was the first time in human history that a country has used chemical weapons for so many years on such a massive scale. This must never be allowed to happen again. Ever. We conducted many studies at Tu Du Hospital on the effects of Agent Orange, and scientists in other countries have conducted studies as well. We know that Dr. Arnold Schecter found high levels of dioxin in Vietnamese mothers’ milk, and that dioxin, like other toxic chemicals, can move from the mother’s body, through the placenta, into the developing fetus. We know that there are ‘hot spots’ in Vietnam, where high levels of dioxin have been found, and where dioxin has gotten into the food chain, so that people have been eating fish and ducks and vegetables contaminated with dioxin.”5

|

Girl born without eyes. Tu Du Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City Thirty-two year old Agent Orange victim, Chu Chi, Vietnam |

Asked if she if she has invited the wartime manufacturers of Agent Orange to visit Tu Du Hospital, and to examine the extensive research she and other Vietnamese doctors and scientists have done into the effects of dioxin on animals and human beings, Dr. Phuong laughs.

“Oh, yes,” she says, “I have invited them many times to visit. But they don’t come. They don’t talk. They hide. I always think that they do believe me. And that some day the United Stats government and the chemical companies will agree to help victims of Agent Orange. But if the companies refuse to pay, then people should not buy their products. All over the world, people should boycott these companies.”

In 2004, Vietnamese victims of chemical warfare filed a class action lawsuit against Dow, Monsanto, and other manufacturers of Agent Orange, charging these companies with war crimes. Federal judge Jack Weinstein presided over this case, a rather ironic, indeed bewildering, choice since Weinstein was the judge who managed to keep Vietnam veterans from having their day in court in 1983. Veterans and their families had wanted to show the world what happens to human beings when they are exposed to chemicals like dioxin. They’d hoped to see all products contaminated with dioxin removed from the market, and an international ban on carcinogenic and mutagenic chemicals. They were asking for justice for victims of chemical warfare, not some insulting payoff for their suffering.

The wartime manufacturers of Agent Orange agreed to an out of court settlement in which they would pay $180 million dollars to the plaintiffs. Veterans called this agreement a “sellout,” not a settlement. A widow of a Vietnam veteran who could prove her husband died from exposure to Agent Orange would receive $3700. A totally disabled veteran would receive $12,000 paid out over ten years. Financiers who subsidized the plaintiff’s attorneys received, as a group, $750,000. An attorney who’d been a “passive investor” received $1,700 an hour for his services. One law firm collected over $1.3 million, while another received more than $1.8 million. The court awarded a total of more than $13 million in attorneys’ fees.6

Twenty years later, Judge Weinstein ruled against the Vietnamese plaintiffs—some of the witnesses died soon after returning home to Vietnam—and appellate courts upheld his decision. According to spokespersons for the manufacturers of Agent Orange, these companies were just following orders, and doing their patriotic duty when they sold the US military more than 20 million gallons of Agent Orange. Therefore, they are neither legally nor morally obligated to pay for any harm that U.S. soldiers and the Vietnamese people allege can be traced to the defoliation campaign in Southeast Asia. That Agent Orange was contaminated with TCDD-dioxin, the most toxic small molecule known to science, and that at least one manufacturer, Dow Chemical, knew that dioxin was “potentially deadly to human beings” makes no difference. John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Baines Johnson signed on to the defoliation campaign and year after year Congress funded the use of herbicides in Vietnam. The use of Agent Orange, then, was an integral part of a noble effort to protect a small-impoverished nation from the threat of a communist takeover.

According to world-renowned scientist and writer, Sandra Steingraber, there are at least 80,000 toxic chemicals on the market in the United States, and between 4-8.000 of these are carcinogenic. “Today, more than 40 percent of us (38.3 percent of women and 48.2 percent of men) will contract the disease [cancer] in our lifespan. Cancer is now the second leading cause of death overall, and, among adult Americans younger than 85, it is the number one killer—beating out stroke and heart disease.”7

The chemical manufacturers of Agent Orange continue to deny that there’s any valid scientific evidence to support the view that dioxin harms human beings. It’s hard to imagine that their scientists are unaware that every known human carcinogen causes cancer in animals, and that nearly everything that causes birth defects in humans also causes birth defects in animals. The chemical companies must know that after injuries and violence, cancer is the number one killer of American children, and that the world scientific community considers dioxin a carcinogen.

Three million Vietnamese people, including 500,000 children, are suffering from the tragic legacies of chemical warfare. In Vietnam, a third and even fourth generation of Agent Orange babies have been born, and no one really knows when this calamity might end. Far too many US veterans are reaching their late fifties and early sixties, only to become ill and die from the effects of long-term exposure to dioxin in Southeast Asia. We are losing our friends and neighbors, our husbands and wives and children to cancer. This epidemic will continue until we demand that multinational corporations stop dumping toxic chemicals into our air, water, and food supplies.

We are the Vietnamese; they are us. We ignore their suffering at our own peril.

Fred A. Wilcox is the author most recently of Scorched Earth: Legacies of Chemical Warfare in Vietnam with an introduction by Noam Chomsky. His other works include Waiting For an Army To Die: The Tragedy of Agent Orange, Fighting the Lamb’s War: The Autobiography of Philip Berrigan, Disciples & Dissidents: Prison Writings of the Prince of Peace Plowshares, Uncommon Martyrs: How the Berrigans and Others Are Turning Swords into Plowshares, and Chasing Shadows: Memoirs of a Sixties Survivor. He is an associate professor in the writing department at Ithaca College.

Recommended citation: Fred A. Wilcox, ‘Dead Forests, Dying People: Agent Orange & Chemical Warfare in Vietnam,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 50 No 3, December 12, 2011.

Notes

1 Jerold M. Starr, Ed. The Lessons of the Vietnam War. (Pittsburg: Center for Social Studies Education, 1991) pp. 261-7).

2 Fred A. Wilcox, Waiting for an Army to Die: The Tragedy of Agent Orange ( New York: Random House, 1983), Introduction.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid, p. 14.

5 Fred A. Wilcox, Scorched Earth: Legacies of Chemical Warfare in Vietnam (Seven Stories Press, 2011), p. 162.

6 Ibid. p. 69.

7 Sandra Steingraber, Living Downstream (Da Capo Press, 2010), p. 47.

Articles on related subjects

• Jon Mitchell, Agent Orange on Okinawa: Buried Evidence?

• Jon Mitchell, Agent Orange on Okinawa – New Evidence

• Jon Mitchell, US Military Defoliants on Okinawa: Agent Orange

• Roger Pulvers and John Junkerman, Remembering Victims of Agent Orange in the Shadow of 9/11

• Ikhwan Kim, Confronting Agent Orange in South Korea

• Nick Turse, A My Lai a Month: How the US Fought the Vietnam War

• Heonik Kwon, Anatomy of US and South Korean Massacres in the Vietnamese Year of the Monkey, 1968

• Nick Turse and Tam Turse, America’s Forgotten Vietnamese Victims: Two Men, Two Legs, and Too Much Suffering

• Taylor Owen and Ben Kiernan, Bombs Over Cambodia: New Light on US Air War

• Ngoc Nguyen and Aaron Glantz, Vietnamese Agent Orange Victims Sue Dow and Monsanto in US Court