Back to the Future: Korean Anti-Base Resistance from Jeju Island to Pyeongtaek

Andrew Yeo

ABSTRACT

Anti-base movements are once again rising in South Korea, this time on the southern coast of Jeju Island. With the Jeju anti-base moving growing, it may be worthwhile to take stock of past anti-base movements in South Korea. Keeping the Jeju anti-base protest in mind, this article takes us back to the Pyeongtaek anti-base movement episode from 2005-07 with an in-depth look at resistance against the expansion of Camp Humphreys from local residents and outside activists. I examine several questions regarding the evolution and efficacy of the Pyeongtaek movement. How did activists merge and frame a local issue alongside more abstract claims of peace and security? What obstacles prevented the movement from achieving success at the level of policy outcomes? What strategies and tactics did South Korean governments use to respond to anti-base protests? I then return to the struggle on Jeju Island, offering some comparisons and reflections on the possibilities which lie ahead for this growing movement.

Anti-base movements are once again rising in South Korea, this time on the southern coast of Jeju Island. Local resistance against the construction of a South Korean naval base has persisted ever since the announcement of Gangjeong village as the future site in 2007.1 News about anti-base protests in Jeju began circulating among activists within the international no bases network and on the blogs of anti-base and different peace organizations after the initial groundbreaking ceremony in January 2010.2 By May 2011, domestic and international mobilization in support of Gangjeong residents was in full swing, with film critic and Gangjeong native Yang Yoon-mo’s hunger strike in prison drawing much concern and attention nationally and abroad.3 Momentum continued to build throughout the summer of 2011, despite—and because of the fact that—riot police descended on Gangjeong in greater numbers and the arrest of movement leaders.

For those who closely observed the last major anti-base movement unfold in Pyeongtaek six years earlier, the struggle in Gangjeong brings us back to the future. Of course key differences exist between the two episodes. Whereas anti-base protests in Pyeongtaek were aimed at preventing the expansion of a U.S. army base, the struggle in Jeju is directed against building a South Korean naval base.4 Additionally, with the development of media technology and social networking tools, the Jeju protests have gained a wider following and international support compared to protests in Pyeongtaek.

Despite these differences, however, certain striking parallels come to mind as the anti-base movement episode in Jeju develops. There are of course the superficial resemblances such as the consecutive days of candlelight vigils, the large tent structure serving as a base of resistance, or the sit-ins and demonstrations blocking construction workers followed by arrests. However, two more significant parallels are worth noting as activists enter an intense phase of anti-base activities. First are the types of frames employed by the movement as local residents and South Korean and international activists attempt to converge on common ground in solidarity. The second is the response from the South Korean government.

|

Jeju Anti-base Movement (Source, Save Prof Yang and Sung Hee-Choi of Jeju Island Facebook page) |

With the Jeju anti-base moving growing daily in August 2011, it may be worthwhile to take stock of past anti-base movements in South Korea. Keeping the Jeju anti-base protest in mind, this article takes us back to the Pyeongtaek anti-base movement episode from 2005-07 with an in-depth look at resistance against the expansion of Camp Humphreys from local residents and outside activists. In this article, I examine several questions regarding the evolution and efficacy of the Pyeongtaek movement. How did activists merge and frame a local issue alongside more abstract claims of peace and security? What obstacles prevented the movement from achieving success at the level of policy outcomes? What strategies and tactics did South Korean governments use to respond to anti-base protests? How did South Korea’s security alliance with the United States influence the strategic interaction between state and society?

This article begins by outlining the strategic and political context behind base politics in South Korea. I first discuss U.S. base relocation and consolidation over the previous decade. I then describe the presence of a security consensus among South Korean policymakers which dominates elite thinking about the U.S.-South Korea alliance. I then provide a detailed account of the Pyeongtaek anti-base movement from 2005-2007. This section highlights how the security consensus influenced the South Korean government’s response to anti-base movements as the Roh administration moved from a strategy of co-optation and delay to one of coercion. In the conclusion, I return to the struggle on Jeju Island, offering some comparisons and reflections on the possibilities which lie ahead for this growing movement.

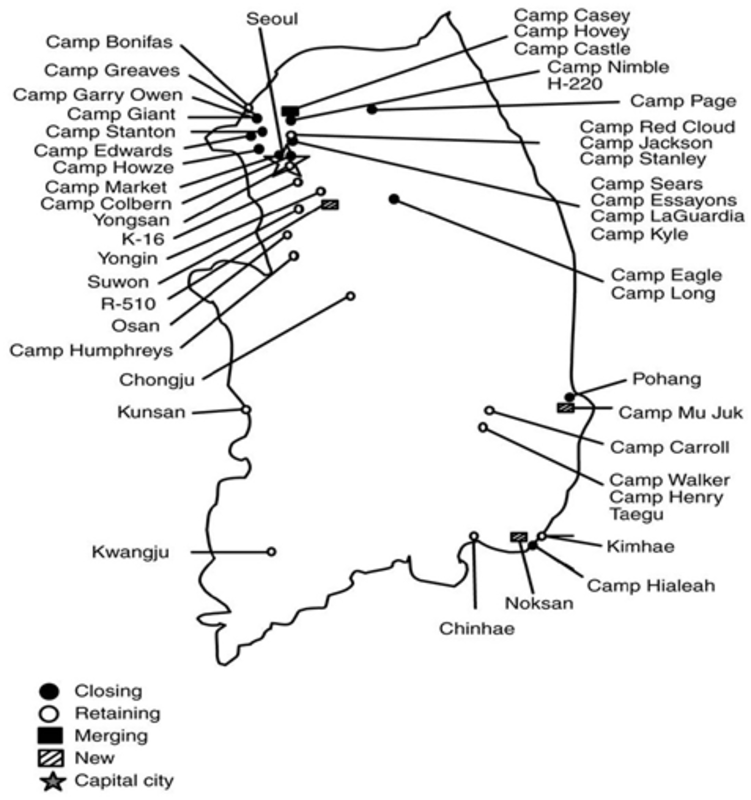

USFK Base Relocation and Consolidation5

Anti-base resistance in Pyeongtaek in the mid-2000s was connected to a larger strategic alliance transformation process pursued by South Korea and the U.S. since 2001. In light of several outstanding land disputes pertaining to U.S. bases, and the dilapidated state of existing USFK facilities, Washington and Seoul initiated the U.S.-South Korea Land Partnership Plan (LPP) in 2001. The LPP was designed as a cooperative effort between the U.S. and South Korea to “consolidate U.S. installations, improve combat readiness, enhance public safety, and strengthen the U.S.-South Korean alliance by addressing some of the causes of periodic tension.”6

The LPP quickly grew outdated in light of changing U.S. global force posture. The United States began considering different options regarding force deployment in South Korea in line with a general reassessment of overseas military presence conducted under the 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review and the Pentagon’s Overseas Basing and Requirements Study. Thus, in April 2003, high-ranking U.S. and South Korean officials discussed a much more comprehensive base realignment project superseding the LPP.7 This included the decision to relocate Yongsan Garrison, USFK headquarters in downtown Seoul, to a location approximately fifty miles south of the capital.8 After ten rounds of negotiations under the Future of the Alliance Policy Initiative (FOTA), both sides agreed to withdraw 12,500 U.S. troops by December 2008 from South Korea, relocate Yongsan Garrison out of Seoul, and consolidate the 2nd Infantry Division to Camp Humphreys in Pyeongtaek.9

|

USFK Base Realignment and Consolidation (Source, Congressional Budget Office, May 2004) |

Elite Security Consensus

USFK transformation in the mid-2000s, and more specifically base relocation to Pyeongtaek, was itself embedded in a wider debate concerning security on the peninsula and the future of the U.S.-ROK alliance. During this period, public opinion surveys indicated a negative change in attitude, particularly among the younger generation, towards the United States.10 The generational gap and shifting trends in South Korean domestic politics consequently polarized South Korean sentiments towards the U.S between progressive and conservative camps with progressives increasingly demanding an alliance on a more equal footing.11 Despite this polarizing trend during a period of alliance turmoil, however, I argue that a security consensus continued to exist among political elites.

What is the basis of a security consensus centered on the U.S.-South Korea alliance? Various institutional and ideational constraints exist which prevent a pro-U.S. consensus favoring U.S. alliance relations from unraveling. These include institutional arrangements such as the joint U.S.-ROK military command structure, as well as the formation of an “alliance identity” produced over decades of close interaction between alliance partners.12 External threats from North Korea, lingering anti-communist ideology, and the institutionalization of national security laws also perpetuate the security consensus within elite circles. Given the high stakes involved in a North-South conflict, and the uncertain security environment in Northeast Asia, South Korean political elites continue to place a priority on the alliance and U.S. troop presence. Political elites agree, at least in principle, that U.S. forces in the mid to long term, are necessary for South Korean security. Other than radicals, very few South Koreans advocate alliance termination, the immediate withdrawal of USFK, or the immediate removal of U.S. bases. Thus, despite the diversity in attitudes and perceptions regarding national security during the late Roh Moo-hyun administration – the most progressive government in South Korea to date – progressives found it difficult to implement foreign policies which diverge far from the consensus.13 As the next section demonstrates, this consensus would present a formidable barrier to anti-base activists.

Pyeongtaek Anti-Base Movement Episode

Although most scholars date the origins of the Pyeongtaek anti-base movement after 2002, the seeds of anti-base opposition in Pyeongtaek date earlier to two local coalition groups.14 A group of local activists from Pyeongtaek formed the Citizens’ Coalition Opposing the Relocation of Yongsan Garrison in November 1990 when U.S. and Korean negotiators considered Pyeongtaek as a potential relocation site for Yongsan Garrison in the late 1980s. The coalition group, composed primarily of local NGOs, evolved into the Citizens’ Coalition to Regain Our Land from U.S. Bases in 1999, and then the Pyeongtaek Movement to Stop Base Expansion in 2001 prior to the announcement of the LPP.

In April 2003 the South Korean and U.S. government formally announced the decision to relocate Yongsan Garrison to Pyeongtaek. The Ministry of National Defense (MND) also announced its plan to expropriate land surrounding Camp Humphreys for base expansion. Of the designated base expansion land, the MND planned to acquire 240,000 pyeong (about 199 acres) of land from Daechuri village.

|

Daechuri Village in Pyeongtaek (Source, KCPT) |

In response, villagers organized the Paengseong Residents’ Action Committee in July 2003 to prevent the MND from taking their farmland. After the conclusion of the U.S.-ROK Future of the Alliance Talks (FOTA) in 2004, the MND agreed to grant the U.S. a total of 3,490,000 pyeong (about 2,897 acres) of land, 2,850,000 pyeong (about 2,366 acres) coming from Daechuri and Doduri village.15 Figure 1 below indicates the area of expansion, tripling the size of Camp Humphreys from 2005.

|

Figure 1: Camp Humphreys Base Expansion Source: Hankyoreh 21, KCPT. Printed with permission from Cambridge University Press |

Acknowledging the gravity of the situation, in May 2004, Father Mun Jeong-hyeon, a prominent anti-base movement leader from previous anti-USFK related campaigns, met with leaders of both the local Pyeongtaek anti-base coalition and the anti-base Residents’ Action Committee. At that point, Father Mun, along with other NGO leaders, decided that the various anti-base movements in Pyeongtaek needed to unify under one national campaign. In early 2005, Mun and other anti-base leaders organized the Pan-National Solution Committee to Stop the Expansion of U.S. Bases (KCPT).

Mobilization

Several leaders active in previous anti-base or anti-USFK related coalition campaigns joined KCPT’s executive committee. KCPT organizers made a conscious decision to include several representatives from the local Pyeongtaek anti-base coalition and the village-level anti-base Resident’s Committee in leadership positions to assure local actors a voice in the campaign.16 KCPT held their first at-large leaders’ meeting with representatives from member groups on March 3, 2005. By July 2005, activists had successfully organized an anti-base coalition campaign linking national-level NGOs, local civic groups, and village residents into one large umbrella coalition. What was originally a local movement in Pyeongtaek had now become a national struggle. Approximately 120 organizations from labor, student, women’s rights, agriculture, human rights, peace, unification, and religious groups were directly or nominally involved in the campaign.

Mobilizing strategies required maintaining support from local and national NGOs as well as the unmobilized masses. The bulk of the organizing work was conducted by activists residing within or near Pyeongtaek. Organizers also included “local” activists representing national-level civic groups, but living in Daechuri village during the campaign. Representatives from national and regional organizations who were coalition members of KCPT attended the members-at-large meetings. These individual representatives were then responsible for mobilizing their local chapters for large events and rallies. Labor unions and student groups, such as KCTU and Hanchongryon, provided the manpower and warm bodies at larger protests. Communication was largely conducted through the internet and mass e-mailing.17

KCPT relied primarily on two types of frames: frames of injustice focused on the issue of livelihood and the forced expropriation of farmers’ lands, and frames of peace which held that U.S. base expansion destabilized Korean and Northeast Asian security. Despite the variegated agenda of national level NGOs under KCPT, the campaign successfully maintained a semblance of unity by placing the local land expropriation issue as its central focus.18 While KCPT may have been more concerned about peace and sovereignty issues, the plight of elderly farmers forcefully evicted from their homeland was more likely to gain traction with the wider public. Framing the anti-base debate in a manner that highlighted immediate consequences, such as the forced eviction of poor farmers, proved much more effective in capturing a wider audience than using abstract frames such as peace and stability in Northeast Asia. Therefore, the support and participation of local residents was essential for KCPT.

KCPT used various tactics to mobilize the public. According to PeaceWind activists living in Pyeongtaek, the most effective means of mobilization was a six week, twenty city publicity campaign tour around the country. KCPT activists contacted regional NGOs in advance about their visit, particularly labor groups who had the largest mobilizing capacity. These groups would then contact other local civic groups and NGOs to listen to Father Mun and other KCPT members discuss the Pyeongtaek base relocation issue.19 Second, NGOs sponsored both press conferences and public forums, inviting the press, government officials, and other activists to discuss pending base-related issues. Third, KCPT sent out electronic newsletters to all member organizations as well as individual members who had subscribed to the listserve. Lastly, KCPT used visual media, art, photo exhibitions, music, and street theater to publicize their cause. In addition to the mobilizing tactics above, KCPT organized three large rallies to attract media attention and raise public awareness about the negative impact of U.S. base relocation to Pyeongtaek. Framing the rallies as “Grand Peace Marches,” these were held on July 10, 2005, December 11, 2005, and February 12, 2006 in Pyeongtaek.

KCPT’s mobilization efforts resulted in large protest numbers ranging from 5,000-10,000 protestors. The movement gradually strengthened throughout the summer of 2005, highlighted by a rally with 10,000 protestors outside Camp Humphreys on July 10. The event drew national attention and KCPT’s momentum sustained through November. With winter approaching, however, other events such as the APEC summit in Pusan, and the WTO meeting in Hong Kong, “distracted” NGO groups from base issues. NGOs had to devote attention to their own parochial struggles.20 The U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations beginning in May 2006 also distracted activists’ (particularly from labor groups) attention further away from U.S. base issues.21

Strategy

The bulk of KCPT’s strategy was oriented towards the larger public and “raising the national conscious of South Koreans,” rather than the South Korean government. In an initial KCPT planning meeting in February 2005, organizers listed two primary objectives of the movement: 1) inform and formulate national public opinion; and 2) form strong solidarity with residents to stop the expansion of bases.22 Mun acknowledged that KCPT was ultimately trying to push the government to change. However, some activist leaders believed influencing public opinion was more effective in pressuring the government to shift policy on security issues than direct government appeals. KCPT’s inaugural declaration illustrated the movement’s focus on the mass campaign:

We cannot tolerate the lives of Pyeongtaek residents to be shaken so violently. Nor can we tolerate the serious threat posed by USFK relocation and permanent military dependency. Therefore, we are going to fight with all our strength to block the expansion of U.S. bases in Pyeongtaek. We are going to use a variety of methods, both on and off-line, and through media outlets, to wage a public campaign to inform the mass public the problems associated with military base expansion and the expanded role of USFK. Through demonstrations at every level, we are going to engage in an intense struggle against our government, which has deliberately ignored its people.23

As mentioned earlier, a strategy targeting the mass public required careful framing of the issue. To draw public attention, activists carefully constructed their slogans to take into account the local nature of the struggle and the plight of evicted residents. The goal was to attract those who may not necessarily have subscribed to the political views of anti-base activists, but agreed with KCPT on principles of human rights. Support from the Residents’ Action Committee was therefore essential. To maintain a local-oriented strategy, activists from national civic groups relocated to Pyeongtaek and occupied houses vacated by residents who had already taken the government’s financial compensation. Villagers and activists repainted homes, painted murals evoking images of peace and village life on the outside of walls, and converted abandoned buildings into public spaces, including a library and café. Residing in empty houses was also a tactic used to prevent the government from beginning base construction. The government would not bulldoze houses still occupied by elderly residents and activists. KCPT activists also participated regularly in the nightly candlelight vigils held in Daechuri, organized festivals, and welcomed visitors to Pyeongtaek and Daechuri village.

To raise national consciousness and influence public opinion on U.S. base issues, KCPT needed media support. This required activists to refrain from making more radical calls such as the immediate withdrawal of all U.S. bases and troops. Hence KCPT resorted to more neutral slogans such as “Stop the Expansion of U.S. Bases.” The rallies in July and December 2005, and again in February 2006, were used to attract media attention. Progressive internet media outlets such as OhMyNews and The Village Voice (Minjung-e Sori) devoted extensive coverage to the Pyeongtaek anti-base movement on their webpage. Hankyoreh, a major progressive-leaning daily also provided frequent, favorable coverage. Hankyoreh 21, the weekly magazine produced by the same media company devoted a section each week to Daechuri residents and KCPT’s campaign.

|

Peace march in downtown Pyeongtaek with international activists. (Source, Andrew Yeo) |

Political Support

Several representatives within the Democratic Labor Party (DLP) and the ruling Uri Party offered their support to KCPT, and tried to raise the relocation issue within the National Assembly. The two National Assembly members most actively supporting KCPT’s struggle were Uri Party member Lim Jong-in, and DLP floor leader and Unification and Foreign Affairs subcommittee member Kwon Young-gil. Following the May 2006 clash between protestors and police, a handful of National Assembly members issued a public statement calling on the government to hold discussions with both NGOs and Daechuri residents. The Uri Party representatives made three specific demands on the government: To stop using strong-arm tactics against civic groups and residents; to release those students and activists arrested during the May 5 clash; and to withdraw all riot police and soldiers occupying the expanded base land area which were dispatched to Daechuri since early May 2006.24 Representative Kwon also raised concerns regarding democratic procedures pertaining to Yongsan’s relocation in a December 2004 subcommittee meeting. In that meeting, Kwon repeatedly questioned the deputy MOFAT minister over the necessity of such a costly transfer. He criticized the government’s lack of transparency in outlining the underlying motives and costs of base relocation which were negotiated between Seoul and Washington.25

Yet the handful of National Assembly members sympathetic to KCPT’s cause had very little power to persuade their fellow representatives on the Pyeongtaek issue. The small faction in the Uri Party and the few DLP members calling for a re-examination of the base relocation project in May 2006 were a minority voice in the Assembly. Moreover, the National Assembly as a whole carried little clout in base politics. Most of this power was held in the National Security Council, or bureaucracies such as the MND and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MOFAT), institutions where anti-base activists had few allies and little access. The leverage the bureaucracies held over the National Assembly can be seen again in the December 7, 2004 Unification and Foreign Affairs subcommittee hearings. In an exchange between Deputy MOFAT Minister Choi Young-Jin and Representative Kwon Young-Kil, Kwon repeatedly demanded the release of FOTA transcripts to examine the details outlining the motives behind Yongsan Garrison’s relocation to Pyeongtaek. However, Deputy Minister Choi sidestepped the issue. Choi claimed that even if documents were declassified, there was no guarantee Assembly members would receive access to the transcripts.26 Without pushing the issue any further, subcommittee members acquiesced to the MOFAT deputy minister’s plea to quickly approve the base relocation bill. The bill passed in a 14-1 vote in favor of base relocation. As one activist-scholar laments, South Korean political elites either blindly acquiesce to the demands of their patron, or because of fears of abandonment, dare not pursue policies which counter U.S. policy preferences.27 Even within the National Assembly, the voting record of National Assembly members on USFK base relocation indicates how political elites continued to support security policies in line with the security consensus. Voting on December 9, 2004, 145 representatives voted in favor of

base relocation while only 27 opposed.28

Government Counterstrategies

The Roh Administration had to walk a fine line in responding to anti-base pressure while also managing its alliance relations with the U.S. For South Korea, it held, the agreement signed with the United States approving Yongsan’s relocation and the consolidation of the 2nd Infantry Division to Pyeongtaek was an “inevitable process” needed to “strengthen the U.S.-South Korean alliance and deter war from [breaking out] on the Peninsula.”29 The MND noted that extensive delays in the relocation project caused by activists would result in a breach in diplomatic trust with Washington. Several other security experts referred to the signed 2004 base relocation agreement as a “promise” to the United States, sealed by the National Assembly’s ratification. President Roh also recognized the potential for further deterioration in the alliance if the Korean government failed to fulfill its end of the bargain on base relocation.

At the same time, the South Korean government needed to be careful not to attract negative publicity. Using force could potentially inflame anti-American sentiment and strengthen support for KCPT. A Pyeongtaek city official working with the MND and USFK on the relocation project stated, “The MND is acting very cautiously regarding forced eviction of residents because the residents are connected to anti-American movements. Evicting residents isn’t that big an issue. It happens. But if residents are forced out, the MND is worried that the anti-American voice will become stronger or face negative reaction from the public.”30 How, then, did the South Korean state respond to civil societal pressure while maintaining its alliance obligations to the U.S.? Influenced by a strong pro-U.S. security consensus and the belief that the future of the U.S.-ROK alliance rested with base relocation and expansion in Pyeongtaek, the government outmaneuvered KCPT and Daechuri residents by employing strategies of delay, co-optation, and coercion.

In a twist of irony, the South Korean government ignored and isolated KCPT by focusing on the local residents. The MND made a sharp distinction between activists and residents, constantly referring to KCPT as “outside forces” engaged in a political struggle. More than concern for the rights of local residents or the national interest, the MND claimed that KCPT was more interested in promoting its own political agenda such as USFK withdrawal.31 In a briefing report, the MND stated, “Last May, external forces [KCPT activists] began residing in Pyeongtaek and joined forces with residents opposed to relocation. But rather than discuss compensation or other livelihood issues, they [KCPT] were opposed to base relocation altogether making dialogue [with residents] difficult.”32 In a follow up press briefing by Defense Minister Yoon, the MND accused anti-base movements of making unrealistic proposals. Yoon also blamed KCPT for creating an impasse in negotiations between the MND and local residents.33 The MND claimed that KCPT had discouraged residents from taking the government’s compensation, and instead, encouraged them to demand a re-evaluation of the entire base relocation project.34

After KCPT’s first major protest in July 2005, the MND decided to hold further discussions with activists and Daechuri residents, hoping residents would sell their land voluntarily if given greater compensation. However, for the remaining residents, the issue was not about compensation, but about democratic principles and their livelihood as farmers. With residents and activists refusing to leave, the MND announced it would conclude the eminent domain process in mid-December and acquire the remaining 20% of base expansion land.35 By January 2006, the MND had legally purchased all the land, despite residents and activists still residing in the village. The government certainly had the power to expel residents and activists by this time. The MND, however, decided to wait until spring to forcibly remove KCPT activists and residents. As activists and Pyeongtaek city officials noted, the Korean government was not likely to “throw out grandmothers in the dead of winter.”36 At this stage, the South Korean government was willing to delay base expansion rather than risk a violent confrontation.37

In February 2006, USFK relayed to the MND that the South Korean government needed to push ahead with the land acquisition, declaring “time was not unlimited.”38 Originally, USFK had expected the land to be transferred to them by December 31, 2005. However, the MND explained to USFK its situation with anti-base resistance, and agreed to transfer the base land by the end of February. Of particular concern for USFK was Congressional funding for base relocation and USFK transformation. At the time, USFK believed that land transfer needed to be completed prior to USFK Commander Burwell Bell’s report to Congress on March 7. As one U.S. military official explained, USFK feared the Appropriations Committee would not provide all the funds necessary to push ahead with USFK relocation if General Bell informed Congress that the expansion land had still not been entirely secured.39 The same USFK official continued that the MND was in a difficult position “trying to find a neutral ground, mediating between its citizens and its security strategy.”40 The above statements suggest that the MND was dragging its feet on the base relocation issue. To maintain the alliance and push ahead with the transformation project, USFK expressed to the MND that Seoul needed to follow through and “make good on its part in a timely fashion.” At the time though, USFK understood the situation faced by the MND, and was not heavily pressuring Seoul to speed up the land transfer.41

However, by April 2006, the MND had shifted from its tactic of delay and foot-dragging to one of resolution and force. One month earlier, MND workers were sent to Daechuri to dig a trench and erect barbed wire around the expanded base area to prevent residents from continuing their farming. However, MND workers aborted their plan as several hundred protestors set fire to fields and physically took over two of the backhoe tractors used to dig trenches.42 Thus in early April 2006, Defense Minister Yoon stated, “The delay in base relocation is coming close to a point where it may create a diplomatic row with the United States. Therefore, from here on out, we will strengthen our possession over the designated base land.”43 The following day, the MND posted an article on its website titled, “Delay in Pyeongtaek base relocation may ignite a diplomatic problem.” The article outlined reasons why the process was being delayed and its impact on the national interest.44 A few days earlier on April 8, the MND had sent 750 workers accompanied by approximately 5,000 riot police to begin filling in the farmers’ rice irrigation system with concrete. The MND blocked the irrigation canals to prevent residents’ attempts to continue farming. Protestors fought riot police and prevented workers from destroying two canals, but workers managed to fill in at least one canal with concrete.45

|

Riot police outside Camp Humphreys in Pyeongtaek (Source, Andrew Yeo) |

Even after these measures, activists and residents continued to cut through barbed wire and plant rice crops. The concrete the MND used to fill the irrigation canals was also smashed by activists, allowing water to flow again onto the farmland. The MND offered direct negotiations on May 1, but after key leaders such as Kim Jitae of the village Resident’s Committee boycotted talks with the MND, Korean officials hinted they would abandon negotiations and secure the land by force. Sensing the gravity of the situation, Prime Minister Han Myeong-sook called an emergency meeting to resolve the stalemate. Han urged the MND and police to look for peaceful means of resolving the dispute, and concluded the meeting with an agreement between residents and MND officials to settle the issue through dialogue.46

After agreeing to dialogue, however, the MND instead went on the offensive and launched a national media campaign on May 3. The MND announced it would dispatch thousands of riot police and ROK soldiers into Daechuri village. Fearing potential public backlash by sending ROK troops (accompanied by riot police) to establish a barbed wire perimeter around the base expansion area, the MND pre-empted KCPT in the national media. In a special press conference, Minister Yoon explained the current situation of the base relocation project, the reasons why riot police needed to be dispatched, and the exact nature of work ROK soldiers would be undertaking in Daechuri. Minister Yoon made clear that soldiers would be unarmed. ROK soldiers’ duties were limited to erecting barbed wire around the perimeter of the expanded base land. In his briefing to the nation, Yoon outlined the history of the Yongsan relocation project and the purpose of base expansion. He then described how the MND consulted the residents numerous times about the importance and inevitability of the base relocation project. The MND was portrayed as reasonable and willing to continue dialogue with residents. In contrast, the government framed KCPT as irresponsible radicals bent on inciting residents for their own political purposes. The MND added that the delay in base relocation caused by KCPT “outsiders” was costing South Korean taxpayers millions of dollars.

Preparing the nation for potential violence, on May 4, the MND in a show of force sent 2,800 engineering and infantry troops to dig trenches and set up 29 km of barbed wire two meters in depth to prevent activists from entering the expanded base land. These troops were accompanied by 12,000 riot police. As soldiers and riot police entered Daechuri before dawn on May 4, KCPT activists in Daechuri quickly alerted their members through e-mail and telephone, mobilizing about 1,000 activists, mostly students, labor union members, farmers, and peace activists.47 About 200 students linked arms and lay flat inside Daechuri Elementary School, the makeshift headquarters of KCPT. As morning approached, riot police physically removed hundreds of activists and students barricading themselves inside KCPT headquarters and bulldozed the building. As soldiers were setting up the barbed wire fence, several activists managed to break through the perimeter and began beating unarmed soldiers with bamboo poles. About 120 police, soldiers, and protesters were injured and 524 students and activists were detained in the two day melee.48 No Daechuri residents were taken into custody. The MND used this information to support its claim that the conflict stemmed from the “outside forces” of KCPT rather than local residents.

The violence in Pyeongtaek, instigated primarily by student activists who were not necessarily KCPT members, dealt a devastating blow to the anti-base movement. The MND and conservative mainstream media capitalized on the violence, claiming that activists had beaten unprotected soldiers who were merely engaged in manual labor.49 Consequently, the general public held anti-base and anti-American activists responsible for the violence in Pyeongtaek. Public opinion polls released by the Prime Minister’s office indicated that 81.4% of Koreans were against the protestors’ use of violence, and 65.8% opposed NGO and civic group involvement in the relocation issue.50 Moreover, rifts within the anti-base movement widened as more moderate civic groups and NGOs began distancing themselves from the radical core of KCPT.51

With its remaining resources, KCPT attempted to mobilize one last major stand. The coalition group organized a candlelight vigil in Seoul on May 13, and a protest in Pyeongtaek on May 14 to denounce the stationing of 8,000 riot police in Daechuri, and the violence “sanctioned” by government forces the previous week. In another display of power and resolve, the government sent 18,000 riot police to Daechuri. To prevent activists from entering Daechuri, the government blocked off all roads into the village, establishing four different checkpoints. With the exception of Daechuri residents, government officials, and mainstream media, no one was allowed to enter the village. As one resident lamented, the entire village had been put under de facto martial law. Unable to enter the village, the 5,000 activists who came in support of KCPT and Daechuri residents ended up protesting either at the train station, or in a village adjacent to Daechuri.

After the May 4-5 incident, the office of the Blue House and Prime Minister stepped forward in response to the violent clashes and the delay in the relocation process. The Blue House issued a statement after the clash, reaffirming its support for USFK base relocation and expansion. Noting that the eviction of residents was inevitable, the Blue House stated, “Hereafter, the base relocation project must progress without any more setbacks to avoid further losses to the national interest.”52 Presidential spokesman Jung Tae-Ho also made similar statements, again citing the delay’s diplomatic and economic costs and the importance of base relocation for the U.S.-ROK alliance.53

Fearing another clash between police and protestors, Prime Minister Han Myeong-Sook, herself a former activist, issued a much anticipated public statement in a live national broadcast. In her televised speech, she expressed regret and sadness for the previous weeks’ violence, and sympathy and concern for residents forced to relocate. Her message implored activists to use restraint, and to express differences of opinion in a legitimate and peaceful manner. However, taking the same position as the MND and Blue House, Prime Minister Han declared, “Fellow citizens, as you know well, from the Korean War up until today, our alliance with the United States has been the basis of our national security, national defense, and economic development. The firm preservation of the ROK-U.S. alliance is necessary for our society and country’s stability and development.”54 Emanating from the prime minister’s office rather than the MND or MOFAT, the statement signified the seriousness of the South Korean government in pushing ahead with base relocation.

Denouement

The Pyeongtaek issue captured the attention of the national media for the next month. The prime minister also met with activist leaders in mid-May to discuss peaceful resolution of the Pyeongtaek issue. Other than agreeing to restraint and non-violence, however, the core differences between the government and activists remained. On June 5, Kim Jitae, Daechuri village head and chair of the Residents’ Committee, turned himself in to local authorities as a condition for resuming talks between residents and the South Korean government. Rather than releasing him after questioning, however, Kim was arrested and placed in prison until December 28. Kim’s arrest dealt an incredible blow to the morale of local residents. Although anti-base protests continued, by June 2006, various umbrella coalition groups, particularly the labor and farmers’ groups, had shifted almost entirely away from the anti-base movement to prepare for protests against the upcoming U.S.-South Korea FTA negotiations.

The government again sent around 15,000 riot police on September 13 to destroy empty homes where activists and the handful of residents were residing.55 In October 2006, workers began leveling the land for construction as the government continued negotiating with the residents. The South Korean government and Daechuri residents finally signed an agreement on February 13, 2007, with the residents agreeing to move out by March 31 to nearby Paengseong Nowhari. With the village residents’ decision made independently from KCPT, KCPT put forth a statement stating it would respect the agreement. The anti-base struggle, which had focused on Daechuri up to this point, would seek a new direction.56

The Pyeongtaek episode demonstrates the constraining role of the security consensus for South Korean anti-base movements in the politics of bases. The security consensus held by state elites created a situation in which the South Korean government needed to balance its alliance obligations to the U.S. while staving off domestic pressure from anti-base movements. Responding to this dilemma, the South Korean government chose to drag its feet and temporarily delay the process of base expansion while co-opting local residents. Although it was KCPT’s residential “sit-in” which effectively blocked the MND from physically taking over the land for base expansion, the delay itself was a strategic response from the MND. The MND was aware that delaying the process in its interaction with KCPT and residents, particularly through the winter, would keep the residents at bay without necessarily strengthening anti-base forces. However, foot-dragging for an extended period also raised diplomatic costs with the U.S. Given the initial USFK transformation timeline to relocate Yongsan Garrison and the 2nd Infantry Division to Camp Humphreys by 2008, the South Korean government feared jeopardizing its alliance relations with the U.S.57 Thus the MND shifted tactics in April 2006. The MND used overwhelming power to block protestors from entering the designated base expansion land, and co-opted local residents while isolating national civic groups. The South Korean government’s media campaign launched against anti-base movements, and its strategic efforts to isolate activists by only negotiating with residents, ultimately led to the defeat of the movement to prevent base construction at Pyeongtaek.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Returning to the present, what are the similarities and differences between Pyeongtaek six years ago and anti-base resistance on Jeju Island today. Like Pyeongtaek, anti-base movements in Jeju lingered for several years as not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) protests organized by local residents before outside activists joined forces with residents. In Jeju, the South Korean navy had first proposed Hwasoon village in western Jeju in 2002, followed by Wimi village in 2005 as the site for construction of a Jeju naval base. Local anti-base resistance developed in both villages which led to the choice of Gangjeong as the next proposed site in 2007.58 Only in the last few years has the Jeju struggle become a global one.

Residents in Daechuri and Gangjeong were unlikely to build a coalition campaign without assistance from the larger activist community. Only after forming solidarity with national and international activists were anti-base movements able to gain significant media attention. In the case of Gangjeong, the development of online networking since the Pyeongtaek movement greatly facilitated awareness of the Jeju anti-base struggle outside of South Korea.

Gangjeong residents and activists have framed their protest in several ways. From a sample reading of an on-line petition letter to President Lee Myung-bak, an international statement of appeal in English, a statement from a major South Korean NGO, and an appeal by Gangjeong residents, three types of frames can be found. The first is a peace/anti-military frame. Activists contend that the naval base is part of a wider regional missile defense system organized by the U.S. As a prime target for military retaliation, the base will ultimately destabilize not only Jeju but the Asia-Pacific region. The second frame evokes the island’s natural environment and beauty. Construction of the base endangers the island’s soft coral habitat, marine life, and volcanic rock formations. A military base is hardly fitting for a beautiful island that has also been declared a peace island and hosts three designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

|

Sunrise along coastal road on Jeju Island (Source, Andrew Yeo) |

The third frame elicits democratic rights and justice, pointing to the lack of transparency and fair representation of those citizens affected by the new base. The first and third frame employed by Jeju activists are nearly identical to those used by Pyeongtaek activists six years earlier. However, to most Koreans, it is likely the second frame which would have the largest appeal. As a friend in Jeju commented, the thought of a military base coming to Jeju does not leave her with a good feeling. This may be the majority opinion of most Jeju citizens. However, these “thoughts” have not yet led to greater island-wide protests as in Okinawa where resistance to the proposed Henoko base expansion has defied the US-Japan plan for more than a decade. Many residents opposed in principle are also ambivalent about taking political action. In addition to building international solidarity, then, activists will need to build frames to mobilize ambivalent Jeju residents from the sidelines to build a cascading effect. There is no guarantee that the South Korean government will heed the majority will, but given that the naval base being built is a South Korean base, Seoul will feel more pressure from its own citizens.

|

Residents and activists in Gangjeong (Source, Save Prof Yang and Sung Hee-Choi of Jeju Island Facebook page) |

Another parallel which takes us back to the future is the South Korean government’s response to anti-base opposition in Gangjeong. As in Pyeongtaek, the MND has accused “outside groups” rather than local residents for politicizing the base issue. An MND official stated, “Since outside groups entered the fray, they have illegally occupied construction sites…They’ve turned this into an ideological and political issue.” 59 On July 15, Seogwipo City police arrested three key activists in Gangjeong: village chief Kang Dong-kyun, Song Kang-ho, and base opposition leader Ko Kwon-il. Kang has since been released, but Song and Ko remain in custody for their attempt on June 20 to climb aboard a barge attempting to conduct surveys. These arrests were preceded by the arrest of Yang Yoon-mo, who was released after 57 days in prison, and Choi Sung-hee for “interfering with base construction.”60 Riot police have been dispatched to the Gangjeong area leading to minor clashes between several protestors and police. And as in Pyeongtaek, residents and activists in Jeju have used these arrests to further highlight the undemocratic nature of base construction.

Activists plan a large protest rally on August 6 with activists and supporters arriving from the mainland to support the local movement. As movement mobilization increases and base construction falls further behind schedule, the South Korean government may ratchet the level of coercion as it did in Pyeongtaek. In Pyeongtaek, late spring and summer were the most active period for protests The MND waited out demonstrations through the winter months when movement activity generally wanes, and then the following spring engaged activists moved aggressively by forcibly evicting any remaining activists residing within the base expansion area.

The key difference in Gangjeong is that the new base under construction is not a U.S. base. Thus, Seoul will not experience the same type of pressure confronted by the Pentagon in 2006. Seoul is not compelled to fulfill alliance obligations through base expansion this time. While the U.S.-ROK alliance may not be directly relevant in this episode, it does not mean that the security logic to build a naval base is absent. Although there is no security consensus operating, ROK elites as well as the majority of Koreans may see the naval base as a greater asset than liability, especially following recent attacks from North Korea. North Korean provocations have undoubtedly created a tough political climate for anti-base activism in South Korea.61

Can Jeju, Korean and international activists build on several powerful frames of injustice to challenge the dominant security paradigm espoused by the state? How will anti-base activists fare against island politics and economic incentives favoring base construction? For residents and activists, victory is largely a matter of creating a discursive space where compelling democratic norms and “common sense” prevail over the strategic logic of bases pressed by the state. Protests, rallies, sit-ins, postings, and tweets are all means of creating such a space.

Andrew Yeo is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Politics at the Catholic University of America, Washington DC. Portions of this article were drawn from Chapter 5 of his recent book, Activists, Alliances, and Anti-U.S. Base Protests.

Copyright © 2011 Andrew Yeo. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

I gratefully acknowledge Cambridge University Press for permission to use portions of my book for this article. I thank Mark Selden for useful comments and suggestions.

Recommended citation: Andrew Yeo, “Back to the Future: Korean Anti-Base Resistance from Jeju Island to Pyeongtaek,” The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 32 No 3, August 8, 2011.

Articles on related topics

• Gwisook Gwon, Protests Challenge Naval Base Construction on Jeju Island, South Korea: Hunger Strike Precipitates a National and International Movement

• Andrew Yeo, Anti-Base Movements in South Korea: Comparative Perspective on the Asia-Pacific

• Norimatsu Satoko, Hatoyama’s Confession: The Myth of Deterrence and the Failure to Move a Marine Base Outside Okinawa

• Yonamine Michiyo, Economic Crisis Shakes US Forces Overseas: The Price of Base Expansion in Okinawa and Guam

• Mitsumasa Saito, American Base Town in Northern Japan. US and Japanese Air Forces at Misawa Target North Korea

• Kageyama Asako, Marines Go Home: Anti-Base Activism in Okinawa, Japan and Korea

• Hayashi Kiminori, OshimaKen’ichi and YokemotoMasafumi, Overcoming American Military Base Pollution in Asia: Japan, Okinawa, Philippines

• Catherine Lutz, US Bases and Empire: Global Perspectives on the Asia Pacific

Notes

1 Comprehensive coverage in English on this movement can be found on the website Save Jeju Island set up by Matthew Hoey. I am grateful to him and many other activists who have enabled outsiders to follow the movement as it unfolds almost in real time. I have not been able to observe anti-base protests in Gangjeong. I have, however, visited Jeju Island on three separate occasions between 2006-2008.

2 Bruce Gagnon of Global Network Against Weapons & Nuclear Power in Space was one of the early international activists drawing attention to the naval base construction in Gangjeong.

3 I first learned of Yang Yoon-mo’s arrest and hunger strike through the Facebook page, “Save Prof Yang and Sung Hee-Choi of Jeju Island.”

4 Some peace activists have attempted to link the ROK naval base as a struggle against U.S. bases and militarism. While there is no direct evidence of U.S. pressure for construction of the naval base, the United States would clearly benefit from a base built to accommodate Aegis destroyers.

5 For more on this topic, see Andrew Yeo. “U.S. Military Base Realignment in South Korea.” Peace Review 22, no. 2 (2010): 113 -20.

6 United States General Accounting Office, “Defense Infrastructure: Basing Uncertainties Necessitate Reevaluation of U.S. Construction Plans in South Korea.” Washington D.C.: GAO, 2003, 1.

7 CBO 2004, 30.

8 GAO 2003, 13. The decision to relocate Yongsan Garrison dates back to a 1991 memorandum of understanding signed between Seoul and Washington. However, dispute over relocation costs, and difficulty in finding an appropriate replacement brought the relocation process to a halt.

9 U.S. State Department, Transcript of U.S and ROK representatives discussing the Alliance Policy Initiative. “U.S. Troop Relocation Shows Strength of U.S.-Korea Alliance”. July 28, 2004. Link. [last accessed August 3, 2011].

10 Eric Larson, Norman D. Levin, Seonhae Baik, and Bogdan Savych, Ambivalent Allies? A Study of South Korean Attitudes Toward the U.S. (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2004); Derek Mitchell, ed. Strategy and Sentiment: South Korean Views of the United States and the U.S.-ROK Alliance (Washington D.C.: CSIS, 2004).

11 Gi-Wook Shin. One Alliance, Two Lenses : U.S.-Korea Relations in a New Era. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2010. no. 4 (2007): 1-12; Chaibong Hahm, “The Two South Koreas: A House Divided.” Washington Quarterly 28 (2005): 57-72.

12 Jae-Jung Suh, “Bound to Last? The U.S.-Korea Alliance and Analytical Eclecticism,” in Rethinking Security in East Asia: Identity, Power and Efficiency, co-edited by J.J. Suh, Allen Carlson, and Peter Katzenstein (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004).

13 Radicals believe that USFK should withdraw from the peninsula given North Korea’s weakened state, but above all because they view U.S. forces as a liability rather than an asset by hindering inter-Korea reconciliation. This attitude is best represented by the Democratic Labor Party and a minority faction in the former ruling Uri Party (now Democratic Party). Progressives are also keen on North-South reconciliation. But differing from radicals, they believe that U.S. forces are still necessary in the mid-long term, albeit on more equal footing.

14 For further information on anti-base movements in South Korea, see Andrew Yeo, “Anti-Base Movements in South Korea: Comparative Perspective on the Asia-Pacific,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 24-2-10, June 14, 2010.

15 The figures comes from activists. The MND reports 3,620,000 pyeong of land being provided to the USFK (about 3,005 acres). See Special Statement Prepared by the MND Minister of Defense.Yoon Kwang-Ung, May 4, 2006. MND News Brief, “Pyeongtaek migoon giji eejeon jaegeumtoh opda” [No reevaluation of Pyeongtaek base relocation]. May 3, 2006.

16 Minutes to KCPT at large leaders’ meeting #1. March 3, 2005. KCTU conference room. Seoul,

South Korea.

17 Interview with KCPT steering committee member, Pyeongtaek, South Korea. November 6, 2005; Interview with Hangchonryon member from Hanshin University, Pyeongtaek, South Korea. November 6, 2005.

18 In reality, however, there was always internal tension regarding tactics, strategy, and even goals of the movement. After violent clashes between police and protestors, differences between grassroots organizations and established NGOs on the base relocation issue became much more pronounced. Grassroots organizations continued to focus on the rights of residents, while larger NGOs challenged the legal process, lack of transparency, and strategic motives behind base relocation and other USFK related issues.

19 KCPT internal document. Organizational meeting notes. February 17, 2005, 10:00am. Seoul, South Korea.

20 Interview with Father Mun Jung-Hyeon. November 7, 2005. Pyeongtaek, South Korea. Bae Hye-Jeong; “Interview with KCPT activist Lee Ho-Sung.” Minjung-e Sori. December 11, 2005.

21 However, labor activists in KCPT helped organize a joint rally against U.S. imperialism with the anti-FTA coalition. A short attempt was made to link military bases and the FTA as an anti-U.S. struggle.

22 KCPT internal document. “Organizational Meeting Notes.” February 17, 2005.

23 KCPT Inaugural Declaration [translated by author].

24 National Assembly press conference public statement. “Pyeongtaek mi-goon gijee hwak-jang gal-deung hae-gyul-eul eui-han woori-ee ip-jang” [Our view on the resolution of the conflict over the expansion of Pyeongtaek base]. May 16, 2006. .

25 National Assembly Records, Unification and Foreign Affairs Committee, 250th Assembly, 16th Meeting. December 7, 2004, 23.

26 National Assembly Records, Unification and Foreign Affairs Committee, 250th Assembly, 16th Meeting. December 7, 2004, 25.

27 Jung Wook-Shik, Dongmaeng-ae dut. [Alliance Trap. Seoul] (South Korea: Samin Press, 2005), 15.

28 National Assembly Records – Main Assembly. 250th Assembly, 14th Meeting. December 9, 2004, 72. Nineteen members abstained from voting.

29 Special Statement Prepared by the MND Minister of Defense, Yoon Kwon-Woong. May 4, 2006. MND News Brief, “Pyeongtaek migoon giji eejeon jaegeumtoh opda” [No reevaluation of Pyeongtaek base relocation]. May 3, 2006.

30 Interview with Pyeongtaek City official, Office of ROK-US Relations. Pyeongtaek, South Korea. February 9. 2006.

31 Special Statement Prepared by the MND Minister of Defense.Yoon Kwang-Ung, May 4, 2006. MND News Brief, “Pyeongtaek migoon giji eejeon jaegeumtoh opda” [No reevaluation of Pyeongtaek base relocation]. May 3, 2006.

32 MND Press Briefing, “Migoon giji eejeon sa-ub gwalyeon” [Related to U.S. base relocation]. May 3, 2006

33 KCPT and the Residents’ Committee denied the MND’s willingness to negotiate. The government claimed it held at least forty-five meetings with both pro and anti-base residents, and 150 formal and informal consultations. Activists, however, stated that the government met the anti-base faction only once for any real dialogue. See MND Press Briefing. May 3, 2006; KBS Sima Toron Transcript, June 9, 2006.

34 Special Statement Prepared by the MND Minister of Defense, Yoon Kwon-Woong. May 4, 2006.

35 To the consternation of KCPT, the court ruling on eminent domain actually completed a month early on November 23, 2005. See Kim Do-Gyun. “Handal ab-dang-gyujin jae-fyul jeol-cha” [Ruling process pushed forward one month]. Minjung-ee Sori. November 22, 2003.

36 Interview with Peace Wind activist. KCPT headquarters. Pyeongtaek, South Korea, December 12, 2005. Interview with Pyeongtaek City official, Office of ROK-US Relations. Pyeongtaek City Hall. Pyeongtaek, South Korea. February 9. 2005.

37 Activists hoped to delay the government either until another hearing opened regarding base relocation in the National Assembly, or until USFK altered its expansion plans to allow Daechuri residents to keep their land.

38 Interview with USFK officials. Pyeongtaek, South Korea, February 3, 2006.

39 Interview with USFK officials. Pyeongtaek, South Korea, February 3, 2006.

40 Interview with USFK officials. Pyeongtaek, South Korea, February 3, 2006.

41 By January 2007, however, General Bell was publicly expressing his displeasure with the delay. His remarks prompted Foreign Minister Song Min-Soon to reassure the U.S. that base relocation would “proceed as agreed.” See Jin Dae-Woong, “Seoul reassures U.S. on base relocation.” Korea Herald. January 11, 2007.

42 Franklin Fisher, “Camp Humphreys residents braced for conflict.” Stars and Stripes. April 7, 2006. http://www.estripes.com/article.asp?section=104&article=35432&archive=true. [last accessed May 8, 2007].

43 Chul-Eung Park, “Pyeongtaek migoon giji eejeon jiyeon-ddaen whegyo munjae bihwa.” [Delay in Pyeongtaek base relocation may spark into a diplomatic problem]. MND News Brief. April 11, 2006.

44 Ibid.

45 Franklin Fisher, “Protestors stop workers from blocking canals near Humphreys.” Stars and Stripes. April 9 2006. [last accessed June 5, 2007]; KCPT/Village Voice. “Gookbangboo, ahb-dojeok kyungcha-lryuk dongwon-hae sooro gotgot pagoi.” (MND mobilizes overwhelming police force, canals destroyed in several places). April 7, 2006.

46 Dae-Woong Jin, “Seoul may halt dialogue with farmers over U.S. base.” Korea Herald. May 2, 2006.

47 Yoon-hyeong Kil, “Yeong won hi dole kilsoo eobs eulee: jak jeon meong yeo myeong ui hwang sae ul.” [The point of no return: Operation: “Hwangs-ae-ul at Dawn”] Hankyeoreh 21, May 16, 2005. p.14.

48 Joo-Hee Lee, “Cheong Wa Dae says no more delays to Pyeongtaek base plan.” Korea Herald, May 6, 2006; Yonhap News Agency. “Pyeongtaek migun giji haeng-jeong daejibhaeng daechi naheuljjae.” [Fourth day of Pyeongtaek anti-base protest]. Chosun Ilbo. May 7, 2006.

49 Seok-Woo Lee, “2m jookbong gong-gyeok. Goon-sok youngji choso buswu.” [Attack with 2m bamboo sticks…destroy soldiers quarters]. Chosun Ilbo. May 6, 2006. [last accessed 8/3/11].

50 Dae-Woong Jin, “Government warns against protests.” Korea Herald. May 12, 2006.

51 PSPD Press Conference, “Pyeongtaek migun giji hawk jang eul dulleossan gal deunge

daehan simin sahoe-ui ibjang gwa je eon” [Civil society’s position on the conflict regarding U.S. base expansion in Pyeongtaek], Seoul Press Center, 7th floor, May 10, 2006.

52 Yonhap News Agency, “Chungwahdae ‘giji eejeon chajil obsi chujin-dwhe-ya.’” [Blue House: “Base relocation must progress without setbacks]. May 5, 2006.

53 Joo-Hee Lee, “Cheong Wa Dae says no more delays to Pyeongtaek base plan.” Korea Herald, May 6, 2006.

54 Transcript of Prime Minister Han Myeong-Sook’s national address. Seoul, South Korea. May 12, 2006. Available here [last accessed 8/3/11].

55 Yonhap News Agency, “Pyeongtaek binjib cheolguh.” [Empty houses in Pyeongtaek destroyed]. Chosun Ilbo. September 12, 2006. [last accessed 8/3/11].

56 See KCPT bulletin board. “KCPT Planned Project for 2007”. February 13, 2007.

57 Base relocation has now been pushed back to 2014.

58 Gwisook Gwon, “Protests Challenge Naval Base Construction on Jeju Island, South Korea: Hunger Strike Precipitates a National and International Movement,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 9, Issue 28 No 2, July 11, 2011.

59 Yoo Jee-ho. “Defense ministry rejects opposition to Jeju naval base plans.” Yonhap News Agency. August 4, 2011.

60 Nicole Erwin and Alpha Newberry. “Rising Tension in Gangjeong,” Jeju Weekly, July 19, 2011.

61 See Yeo, “Anti-Base Movements in South Korea: Comparative Perspective on the Asia-Pacific.”