Translation by Bret Fisk

Abstract: The author situates Tokyo air raids and the postwar movement within the context of international law and the indiscriminate bombing of civilian populations in urban areas.

Introduction

Research on the Great Tokyo Air Raid didn’t begin in earnest until the 1970s. During that time, the Viet Nam War was increasing in intensity and fierce bombing raids were carried out against the North Vietnamese by the American military. As this conflict in Viet Nam provided an impetus for air raid survivors in Japan to rethink their own experiences, American military documents related to the raids were also being declassified. A movement began for Japanese survivors to begin recording their own history.

One such popular movement was commenced to record the details of the Tokyo raids and their effects on the civilian population. The Association to Record the Tokyo Air Raids was born and, with the assistance of the metropolitan government, began to collect and organize not only handwritten accounts from survivors but also other types of air-raid source materials in both Japan and America. These were collectively published between 1973 and 1974 as the “Tokyo Daikushu–Sensaishi” (“Great Tokyo Air Raid—War Damage Documentation”).

One characteristic worth noting is that the above efforts were not carried out within academia, but were rather the result of research carried out on a grassroots level. The Association itself would continue to collect materials related to the air raids while also becoming involved in another movement to seek commitment on the part of the Tokyo government to build a memorial hall dedicated specifically to the air raids and the damage they inflicted on the city. This movement was ultimately unsuccessful. (Editor’s note: for an analysis of the aforementioned movement, see “Place, Public Memory, and the Tokyo Air Raids” by Cary Karacas)

In 2002, however, the Center of the Tokyo Raid and War Damages was built using privately donated funds and has since become an important hub for continued research into the air raids. It is also an active collector of air raid related materials. On the sixtieth anniversary of the raids in 2005, the Center joined with the Edo-Tokyo Museum, the Toyoshima Ward Local History Museum, and the Sumida Local History Museum to work on a common research project and exhibit. Survivors and family members also joined together to put on a special air raid exhibit in the Roppongi Hills building complex. In 2006, the War Damages Research Center organization was established within the confines of the Center itself, and it has been the recipient of Ministry of Education funding to help with its mission to produce “documentation and exhibits on the Tokyo air raids” since 2007.

These developments considered, it seems that research into the air raids has entered a newly productive era.

Indiscriminate Bombing and International Law

Regarding the beginnings of aerial bombing, it is important to note that airplanes have been used in war almost from their very invention in the twentieth century. It should also be noted that they were used by Britain, Italy, Spain and other powerful nations as a tool in their quest to acquire new colonies and suppress independence movements within the colonies already in their possession. Cruel measures such as the dropping of poison gas were even employed without provoking any international outcry. It was only when the European nation of Spain itself was attacked in Guernica by German and Italian forces that the bombing of civilian residential areas began to draw protest.

International laws regarding aerial bombing had existed since 1922 in the form of the Hague Rules of Air Warfare. These rules prohibited bombing aimed at noncombatants and also stipulated that measures be taken to limit the effects on civilian populations of legitimate attacks against military or military-related targets. Six countries, including Japan and the United States, signed the treaty, but because none of these nations went on to ratify it, the agreement had no real binding power.

On the other hand, when Japan and the other nations went on to develop their own rules and policies regarding aerial bombing, the Hague rules were respected as a valuable basis. For example, the Japanese navy produced “Standards for Air Warfare” in July of 1937 that relied heavily on the Hague Rules of Air Warfare. In addition, while still recognizing the validity of air attacks on expressly military targets, the League of Nations would eventually react to the Japanese bombing of Chongqing and the attack on Guernica by resolving to “protect citizens from air raids in time of war” in accordance with the Hague rules. In this way, limitations on air warfare had become an established principle of customary international law by the end of the 1930s.

However, the Japanese navy was able to justify its actions against Chongqing on the basis that any city defended by aircraft and anti-aircraft cannons must be considered a type of base and was therefore a legitimate target. In other words, one could make the argument that the Great Tokyo Air Raid and other attacks against the Japanese mainland made by the United States were quite literally extensions of the same reasoning that Japan itself had utilized in its bombing of Chinese cities. In spite of this fact, the Japanese military declared that the indiscriminate air raids it suffered were in violation of international law. United States Army Air Force crews subsequently shot down and held as prisoners of war were tried, with some executed, under military laws instituted in July 1942. At times, these executions took place without even holding a military tribunal.1

The Great Tokyo Air Raid: Background and Decision

The United States military began to use its newly developed B-29 bombers against lands ruled by Japan in 1944. Initial raids were conducted from bases located in the Indian city of Kharagpur from June 5, 1944 to January 11, 1945. Targets included a railroad switchyard and bridge in Bangkok, a switchyard in Rangoon, and the docks of Singapore. After an airfield was constructed in the city of Chengdu (Sichuan Province) China, air raids targeted the Japanese island of Kyushu as well as Hankou, Nanking, Shanghai, Jeju, Taiwan, and Manchuria from June 16, 1944 to January 17, 1945. Furthermore, once the Mariana Islands of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam were occupied, airfields were constructed that allowed direct attacks on the Japanese home islands and Korea beginning on November 24, 1944.

The direct attacks on the Japanese homeland can be divided into two groups: those that occurred before March 10, 1945 and those that occurred after. Air raids belonging to the first group, occurring between November 24, 1944 and early March 1945, were characteristically high-altitude precision daytime raids that targeted such facilities as aircraft plants. The Nakajima Aircraft Company was designated the primary target, but when strikes against this factory were not possible, secondary targets within the various Tokyo wards were attacked. The second group of air raids against Tokyo includes five that occurred between March 10 and May 26, 1945. There were all low altitude night raids and made use of enormous amounts of incendiary bombs to burn out large sections of civilian residential areas. It should also be noted that the second group of air raids included precision attacks on military facilities. Both groups also included bombings on Tokyo that were carried out when other cities slated for attack could not be hit or even when returning B-29s merely had bombs left over and used them on Tokyo before returning to base.

Other raids included smaller aircraft that were launched from aircraft carriers. Bombers that took off from Iwo Jima were also known to strafe Tokyo with machinegun fire. If these attacks and others against Tama and the Izu Islands are included, the total number of times that Tokyo was bombed exceeds one hundred.

The actual air raids ended up falling into these broad categories, but it is clear that five types of military and industrial targets had already been designated as early as November 1943. These targets included bridges, shipyards, and aircraft. In April and May of 1944, it was decided to attack six major cities, including Tokyo, after enough B-29s became available. These attacks were to come during the seasonally windy months from March 1945, and were to specifically target urban areas with large numbers of incendiary bombs. Up to October 1945, proposed targets had been limited to aircraft production sites and urban areas. This process demonstrates how the carpet bombing of urban areas was not simply the brainchild of Curtis Le May, but was actually organized and designed by the United States Air Force in general.

Details of the Great Tokyo Air Raid

There is a misconception that during the March 10 raid the bombers first created a wall of flames around their target area and then began to drop incendiaries directly over the fleeing civilians. In reality, however, the bombers dropped huge M-47 incendiaries in order to create a conflagration that would act as a beacon to guide subsequent bombers and allow them to drop their payloads over the designated area as quickly as possible. There was no need to actually surround the target zone with flame.

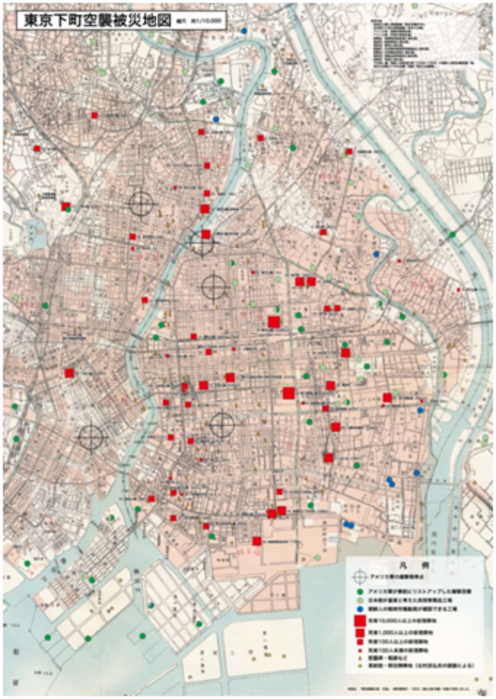

Parenthetically, we can note here that this target zone included the following neighborhoods that the American military recognized were densely populated rural areas particularly vulnerable to incendiary attack: To the west—the areas just bordering the imperial palace and Ueno Park; to the east—Honjo Ward (the southern part of present day Sumida Ward) and Fukagawa Ward (the western edge of present day Koto Ward); to the north—as far as the Johban Line train tracks; to the south—as far as the Eitaibashi bridge. The total wards affected were: Honjo, Fukagawa (northern part), Asakusa (eastern area of present day Taito Ward), Shitaya (western area of present day Taito Ward), Kanda (northern part of present day Chiyoda ward), Nihonbashi (northern part of present day Chuo Ward), and Arakawa (southern part).

|

Map showing in pink the portion of Tokyo destroyed in the March 10 firebombing. The cross-hair marks are the points where lead B-29 crews were to establish marker fires. |

Another misconception is that the Americans spread gasoline before dropping the incendiaries. Although the M-69 napalm incendiary bombs contained gasoline, gasoline itself was not dropped independently. As demonstrated by these misconceptions, it is true that the statements of survivors do not always square with the realities of the air raid. On the other hand, survivor memories can often help correct mistakes in the official records. It is necessary to give ear to both sides.

Research into the number of casualties has also progressed. Currently 105,400 individuals are honored by the Tokyo Memorial Hall—a figure which reflects the total number of confirmed deaths. This number includes not only the remains actually interned within the hall, but also includes 17,000 persons whose bodies were claimed by surviving family members directly after the raid as well as 8,300 persons whose remains would be claimed in later years following initial temporary internment at various sites throughout the city. However, many of the dead were never discovered at all so the actual number of casualties must be greater than 105,400.

Victim Compensation

While the war continued in February 1942, legislation was passed that would provide financial assistance not only to veteran soldiers and other military personnel, but also to civilians who had lost family members, sustained war-related injuries, or whose homes had been burned down. These benefits were extended to both Japanese citizens and the inhabitants of occupied Korea and Taiwan. However, after the war ended, in 1946, other welfare laws were established. At this point all such programs, as well as veterans’ benefits and other war-related welfare programs, were abolished.

After the American occupation ended, benefits providing assistance to injured veterans and families that had lost members through military service were instated in 1952. Such benefits were once again extended to healthy veterans beginning in 1953.

Civilians who had suffered in the war began to demonstrate for reinstitution of national compensations. However, the government would only recognize people who had been drafted to work in factories, students and youth in similar work programs, and members of civil defense forces on the basis that they had worked in direct cooperation with the military to further the war effort. Those injured in the air raids and those who had lost family members were left without any assistance whatsoever.

During the 1980s, civilian victim groups began to sue the government for compensation. The most famous of these trials took place in Nagoya, but in Tokyo as well individuals have sought government compensation through legal channels. However, these demands have all been denied on the grounds that the sacrifices and damages of war are something that must be “endured” equally by all members of society due to these sacrifices and damages having been incurred during a time of special emergency when the very survival of the nation was at stake. Even so, another suit was brought against the government by a group of surviving family members of air raid victims in March 2007. In addition to compensation, the group seeks recognition of the fact that the Tokyo air raids were a violation of international law.

It is clear that a variety of problems caused by the Great Tokyo Air Raid remain unresolved. These problems necessitate further academic research that fully respects the feelings of the air raid victims and their bereft family members.

This is the English translation of Yamabe’s article originally published in Yamabe Masahiko 2008, ‘Ima, Tōkyō Daikūshū o Kangaeru,’ in Nihon Terebi Hosomo Kabushiki Gaisha (eds), Tōkyō Daikūshū: Ano Hi o Ikinuita Naasutachi no Shōgen, Tokyo: Nihon Terebi Hosomo, pp. 153-162.

Recommended citation: Yamabe Masahiko, Thinking Now about the Great Tokyo Air Raid 今、東京大空襲を考える, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 3 No 5, January 17, 2011.

See the following articles included in this special issue:

Bret Fisk and Cary Karacas, “The Firebombing of Tokyo and Its Legacy: Introduction 東京大空襲とその遺したもの−−序論”

Sumida Local Cultural Research Center of Taize, “That Unforgettable Day–The Great Tokyo Air Raid through Drawings あの日を忘れない・描かれた東京大空襲”

Bret Fisk, “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived 被災者が語る東京空襲”

Katsumoto Saotomo, “Reconciliation and Peace through Remembering History: Preserving the Memory of the Great Tokyo Air Raid 「歴史の記憶」から和解と平和へ東京大空襲を語りついで”

Cary Karacas, “Fire Bombings and Forgotten Civilians: The Lawsuit Seeking Compensation for Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids 焼夷弾空襲と忘れられた被災市民―東京大空襲犠牲者による損害賠償請求訴訟”

Articles on relevant subjects include:

Robert Jacobs, “24 Hours After Hiroshima: National Geographic Channel Takes Up the Bomb”

Asahi Shimbun, “The Great Tokyo Air Raid and the Bombing of Civilians in World War II”

Yuki Tanaka and Richard Falk, “The Atomic Bombing, The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and the Shimoda Case: Lessons for Anti-Nuclear Legal Movements”

Marilyn B. Young, “Bombing Civilians: An American Tradition”

Mark Selden, “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq”

Yuki Tanaka, “Indiscriminate Bombing and the Enola Gay Legacy”

Notes

1 Editor’s note: See related Imperial Japanese Army documents, Regarding Treatment of Flyers of Enemy’s Air Raiding Planes, here.