In Search of an Apology

In 2007, an extraordinary apology by Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō appeared in print. It begins with an acknowledgement that Japan’s indiscriminate bombing of civilians living in the Nationalist Chinese wartime capital of Chongqing beginning in 1938 violated international law and gave the United States a justification for its own devastating incendiary raids on Japan’s capital. The prime minister also admits that, by not capitulating to the United States once defeat became inevitable, the Japanese government essentially permitted the firebombing of Tokyo and thereafter the rest of urban Japan in 1945. To show the sincerity of its apologetic stance toward Tokyo air raid victims, the state agreed to provide financial compensation to survivors and bereaved family members, conduct a comprehensive survey of the dead, and build a memorial both to honor them and to serve as a reminder that the air raids had occurred. The letter exists only as a suggested template, however, written by plaintiffs who sued the Japanese government seeking such an apology and compensation of 1.23 billion yen (approximately $15 million).1 In March 2007, sixty-two years after the catastrophic Great Tokyo Air Raid forever changed their lives, 112 survivors and bereaved family members announced their intent to sue the government for redress. The following month, the plaintiffs, the oldest of whom was eighty-six and whose average age was seventy-four, filed the suit with the Tokyo District Court.2

|

Lawsuit plaintiffs, lawyers, and supporters near the Tokyo District Court, 2009 |

Standing on the courthouse steps as the lawyers explained their case to assembled media, one plaintiff, clutching memorial tablets as he spoke, remembered how he searched in vain for his parents’ remains for four years after the firebombing. Another, whose parents, siblings, and right arm were all claimed by the air raids on Tokyo, expressed her hope that the lawsuit would reveal the discrimination that she and others endured long after the war ended.3 The lawsuit may be seen as the latest collective effort – and certainly among the last, given the advanced age of the participants – on the part of Tokyo air raid survivors and bereaved family members to call attention to the “forgotten holocaust” of March 10, 1945, that destroyed much of Tokyo’s built-up area, killed an estimated 100,000 people, injured at least 40,000, and displaced one million.4 It also assumes its place among the many other redress cases brought in the last couple decades by a variety of groups in and outside of Japan – including atomic bomb survivors, former sex slaves (‘comfort women’), forced laborers, former prisoners of war, civilian internees, colonial veterans, and war orphans (zanryū koji) – demanding state compensation for war-related suffering.5

|

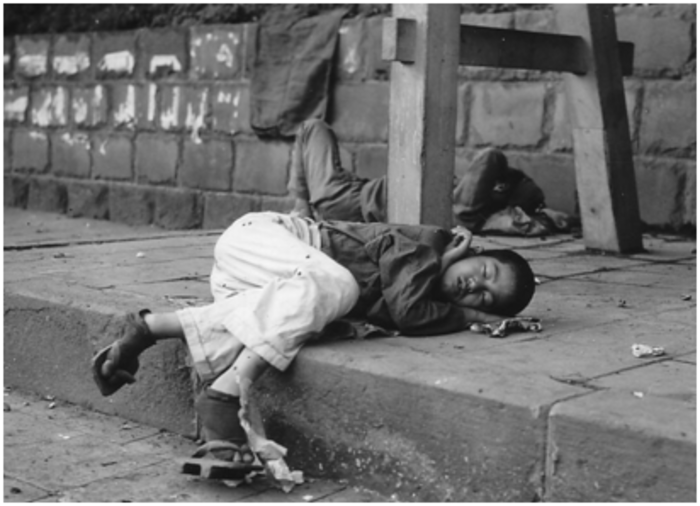

March 10, 1945 Tokyo air raid victim Source: U.S. National Archives Homeless orphan in postwar Tokyo Source: U.S. National Archives |

The Path Leading to the Lawsuit

A central figure in the lawsuit is its lead plaintiff, Hoshino Hiroshi, who experienced the March 10 raid as a twelve year old. While escaping the flames with his mother and siblings was hellish enough, Hoshino focuses on the resulting scenes of devastation when he explains, in relation to the firebombing of Tokyo, his commitment over the last few decades to being a “memory activist.”6 As he walked through devastated neighborhoods to find out about the safety of relatives, he passed a multitude of dead bodies, including mothers holding their children, most burned beyond recognition. The state’s mobilization of Hoshino to assist with the collection of corpses for burial in temporary gravesites further forced him to face the ultimate result of the United States’ decision to embrace what geographers have referred to as both “place annihilation” and “urbicide” as a form of warfare against Japan.7

In the mid-1990s, Hoshino, in collaboration with the Yanagihara neighborhood association leader and bereaved relatives still living in the area, began a small-scale project to produce a map of the Yanagihara district of Honjo Ward (now Sumida Ward) as it existed before being obliterated by the firebombing, and to collect the names of killed residents. These actions led to the formation of the Association to Record the Names of Tokyo Air Raid Victims (Tōkyō Kūshū Giseisha Shimei no Kiroku o Motomeru Kai), which began a project to compose an extensive list of names of the dead from Tokyo’s wards destroyed by the March 1945 firebombing, an activity that the Japanese government, both in the wake of the air raids and throughout the half-century after its occurrence, had failed to do.8

|

Tokyo Air Raid Lawsuit Lead Plaintiff Hoshino Hiroshi Photo by Cary Karacas |

Working from a small office located above a dilapidated Sumida Ward coffee shop, Hoshino and a few other air raid survivors encouraged neighborhood residents who personally knew of people who had died in the firebombing to complete an “Air Raid Victim Report.”9 In addition to naming the dead, the report encourages witnesses to write reflections about the deceased and to indicate the victim’s specific place of residence prior to the firebombing. To focus on the place of death was in most cases a near impossibility due to the severity of the firestorm and the fact that most victims – those not among the many taken by currents into Tokyo Bay and beyond after they had jumped into canals and the Sumida River to subsequently perish – were quickly buried in mass graves. Leafing through the approximately 8,000 reports that the group collected, now placed in binders lining the shelves in the association’s office, the observer is struck by the fact that the March 10 raid victims overwhelmingly fall into one of three categories: adult females, people over fifty, and people under ten years of age. Not infrequently, a long list of names, indicating the death of most or all of an immediate family, dominates the individual report. In a typical example, one lists a thirty-two year old female named Haru, followed by her seven year old daughter Ayako, six year old son Takashi, and four year old son Atsushi.10

A handful of private citizens, however, did not have the financial and human resources required to undertake a citywide and countrywide search for information about tens of thousands of air raid victims. As such, Hoshino campaigned to compel the Tokyo Metropolitan Government to take over the project. After he raised the issue in the local media and successfully petitioned ward assemblies and other local legislative bodies to pass resolutions calling for it to do so, in 2000 the Tokyo Metropolitan Government officially took over the task and by 2005 had gathered approximately 76,700 names of individuals killed in all raids on Tokyo.11 Those names now fill a couple dozen “books of the dead” that occupy the interior of a controversial monument constructed for air raid victims in Sumida Ward’s Yokoamicho Park.12

|

Names of air raid victims inside Yokoamicho Park monument Photograph courtesy of Bijutsu Press |

Hoshino Hiroshi’s work as a memory activist continued with the formation of the Association of Bereaved Family Members of Tokyo Air Raid Victims (Tokyo daikūshū giseisha izoku kai) in 2000. Consisting of around 700 members, the association began meeting annually the following year. Air raid survivors, bereaved relatives, and war orphans recalled their experiences through participating in group discussions, recreating maps of their neighborhoods as they existed before being destroyed, and taking memorial walks in which they visited significant areas such as Koto Ward’s Kinshichō Park, site of a mass grave holding over 12,000 bodies until the late 1940s.13

|

Association of Bereaved Family Members of Tokyo Air Raid Victims office in Oshiage, Sumida Ward. Photo by Cary Karacas |

The meetings also became a forum in which participants criticized the Japanese government’s treatment of those killed, injured, orphaned, and otherwise affected by the raids. Discussion of the government’s failure to provide relief for air raid victims dominated the 2004 annual meeting, and throughout 2005 the association began preparations for a lawsuit by assembling a pro bono legal counsel composed of over one hundred lawyers “from Sapporo to Okinawa” and collecting written statements from potential plaintiffs whose lives were affected by the March 10, 1945 firebombing.14 Given that over six decades had passed since the event, the vast majority of the 112 plaintiffs, comprised mostly of air raid survivors and relatives of firebombing victims, were children at the time of the raid. About half directly experienced the firebombing, and most of the remaining plaintiffs were among the roughly quarter million children who, evacuated from Tokyo beginning in 1944, lost family members in the firebombing. The individual plaintiff reports, important documents in and of themselves in that they convey the catastrophic impact of the firebombing at the scale of the family unit, show that the March 10 raid affected people in a variety of ways. The most obvious are physical injuries, the deaths of family members, and the destruction of private property. Many plaintiffs also mention the lingering effects of PTSD, prolonged impoverishment, and discrimination faced throughout the postwar period.

Plaintiffs who experienced the March 10 raid concentrate on the loss of family members and the horror of the event, in particular seeing and smelling the corpses.15 In a typical example, one plaintiff, six years old at the time of the raid, writes how she became forever separated from her mother – an all too common occurrence – during the chaos of people attempting to escape the conflagration, and continues to live with the memory of witnessing mountains of bodies. One seventy-three year old plaintiff, the only one in her family to be evacuated from the capital, lost her parents and five siblings, and from then onward lived a miserable existence while working in Tokyo factories and pachinko parlors. Another plaintiff, twenty-one years old in 1945, discovered that his parents had died on a canal embankment in Honjo Ward near their home. Although a government plan had been in place for managing corpses in the event of casualties following an air raid, the state’s inability to deal with so many victims forced him to collect some wood that had failed to burn in the firestorm and cremate the bodies himself. He carried away little more than his mother’s Buddhist prayer beads and father’s gold teeth. Their stated reasons for joining the lawsuit are as varied as their wartime experiences and injuries. The plaintiffs joined in order to preserve the memory of family members killed in the March 10 raid; to express their feeling of being ill-treated by the Japanese government; to make the government admit its “war responsibility” and role in the deaths of so many people in the air raids; to express their anger at Emperor Hirohito for honoring Curtis LeMay in recognition of his postwar involvement with assisting Japan’s Self-Defense Forces; and to call for the construction of an appropriate air raid memorial and charnel house for the remains of unidentified firebombing victims. A reason given by one plaintiff points to the heart of the matter in terms of the prevalent view among air raid survivors regarding the government’s willed ignorance about the raids: “I want the state to understand how much incredible suffering was experienced.”16

Charges Brought Against the Japanese Government

Throughout a series of nine court sessions that lasted from May 2007 to May 2009, lawyers for the plaintiffs presented a number of arguments to justify the demand for compensation and an apology.17 Echoing geographer Kenneth Hewitt’s observation that the results of terror bombing during World War II “were not uniformly or randomly scattered across the whole land and society,” lawyers for the plaintiffs presented casualty estimates, damage reports, and the personal experiences of a few of the million people whose lives were irrevocably altered by the March 10 raid in order to convey a sense of the exceptionally catastrophic nature of the event.18 Thereafter, they charged that the state acted irresponsibly by failing to conduct a thorough survey of air raid casualties and to confirm the identities of the dead. A core argument is the contention that the United States, via its indiscriminate bombing of civilians in the March 10 raid, was liable to pay compensation according to Article Three of the 1907 Fourth Hague Convention – Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Japanese government, argued the plaintiffs, should be held responsible for agreeing to article 19(a) of the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty in which the country waived “all claims of Japan and its nationals against the Allied Powers and their nationals arising out of the war or out of actions taken because of the existence of a state of war….” Finally, plaintiffs argued that the defendant Japanese government violated numerous legal statutes, including Article 14 of the current constitution that guarantees equality under the law, by not providing financial relief to air raid sufferers while offering generous benefits to veterans and their families.

In suing the Japanese government, the plaintiffs confronted a multi-layered defense bulwark that has protected the state against an onslaught of war-related redress claims over the last few decades.19 One layer of defense meant to deter compensation claims brought by Japanese citizens is the “endurance doctrine” (jūninron), which holds that, since Japanese civilians equally experienced severe hardship during a time of national emergency, no particular group can receive special treatment from the government.20 This endurance doctrine has usually withstood significant challenges, and when the state has been forced to provide assistance to civilians for war-related suffering – such as atomic bomb sufferers – it has acted to present the suffering as exceptional so as not to open itself up to further compensation claims.21

The Japanese government’s wartime approach to its citizens affected by the war offers an important contrast to its “endurance doctrine”. In 1942, it established the “Wartime Damages Protection Act” (Senji saigai hogo-hō) to provide financial relief to civilians directly impacted by the war through the death of a civilian family member, bodily injury, or loss of personal property.22 Given the enormous damages and dislocation caused by the United States reducing most of Japan’s cities to rubble and ash three years later, it is no surprise that 920 million yen, a majority of the financial relief paid about by the state under the law’s provisions, went to over 17 million people affected by the air raids. That relief came to a complete halt in May 1946, however, when the Supreme Command for the Allied Powers abolished the “Wartime Damages Protection Act” as well as laws that provided financial assistance and disability pensions to veterans, civilian auxiliaries of the military, and their surviving families. In 1952, soon after regaining sovereignty, the government reinstated laws providing financial support to veterans and families, reestablishing the “Act on Relief to Wounded and Sick Retired Soldiers and Bereaved Family Members” (Senshōbyōsha senbotsusha izoku nado engo-hō) and passing the “Soldiers’ Pension Law” in 1953.23 The Japanese government, however, did not reinstate relief benefits to “civilian war victims” (ippan sensaisha). This fundamental shift from the wartime approach to relief did not go unnoticed. In a November 1952 Asahi Newspaper opinion piece, for example, social security specialist Suetaka Makoto argued against the development of a pension system that favored one segment of society over others – pointing explicitly to the exclusion of those orphaned and widowed by air raids – on the grounds that it created a privileged class and thereby contradicted the constitutionally guaranteed principle of equality under the law.24 While the government expanded the relief laws over the next two decades to include more military-related claims, it ignored calls to provide relief for civilian war victims. Subsequent legislative attempts to provide financial relief failed as well. In 1973, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party blocked the passage of a War Damages Relief Bill (Senji saigai engo hōan), as it did when lawmakers from opposition parties in the Diet collectively presented the bill for consideration fourteen times throughout the 1980s.25

The Court Verdict

At the very first oral proceeding in 2007, the Japanese government asked the court to reject all claims, arguing that they were merely a rehash of those made in a lawsuit brought by victims of the firebombing of Nagoya City, which the Supreme Court dismissed in 1987. The state reaffirmed its long-held stance that it is not constitutionally mandated to provide for compensation related to air raid losses, which it considers as part of overall war damages.26

The Tokyo District Court allowed the trial to continue, and in proceedings over the next two years the defendant Japanese government largely remained silent during the court proceedings. One of its few actions was to provide a brief list of war damage reports requested by plaintiff lawyers.27 Those surveys, countered lawyer Kuroiwa Akihiko, did not include an examination of the particular effects of the air raids or a coordinated and comprehensive attempt by the government to find out who was injured and killed.

At the final proceeding that took place in May 2009, the plaintiffs submitted a 150-page legal brief, which the government, declining to offer a closing statement, characterized as not worthy of acknowledgement. Perhaps aware of how the court would eventually rule, the plaintiffs’ head lawyer, Nakayama Taketoshi, stated that the purpose of the lawsuit was to tell the situation of the Tokyo air raids, to make clear the suffering of the plaintiffs, and to raise awareness of the state’s responsibility to deal with this war-related issue. Another attorney assumed a more combative tone by charging that the government was directly responsible for the Tokyo air raids and its resulting casualties by its continued prosecution of the war after it became apparent that Japan had lost.

In December 2009, the Tokyo District Court ruled against the plaintiffs and ordered them to pay all costs associated with the trial. It ruled that it is not possible to determine conclusively that Article Three of the 1907 Fourth Hague Convention became a part of international customary law or that it gives individuals the right to seek damages when the laws of war are violated. Then, essentially adopting the state’s long-held “endurance obligation” position, the court stated that it would set a discriminatory precedent by ruling in favor of the plaintiffs due to the fact that the almost the entire Japanese nation had suffered during the war. In another echo of previous court rulings on war-related compensation cases, the Tokyo District Court held that only a legislative solution could resolve the issue of civilians– in particular air raid victims and orphans – who might warrant financial relief for wartime losses.28

Conclusion

|

2009 Asakusa “Peace Walk” Courtesy Hoshino Hiroshi Sumo wrestler near Kameido Station, Koto Ward, signs petition in support of Tokyo air raid lawsuit, 2008. Courtesy Hoshino Hiroshi Lawsuit plaintiffs and supporters attending a public meeting in Taito Ward, 2009. Photo by Cary Karacas |

Given the Japanese court system’s well-established record of rejecting war-related compensation lawsuits, observers of this particular lawsuit – and possibly some of the participants themselves – did not expect the Tokyo District Court to rule in favor of the plaintiffs. Despite the ruling, however, the plaintiffs can claim to have made important progress in the overall movement to ensure that the air raids are not forgotten. Via the first major lawsuit filed by a large number of people affected by the March 10, 1945 firebombing of Tokyo, a public record exists that conveys the conviction that the Japanese government bears responsibility for allowing the air raids to take place and for its subsequent neglect and mistreatment of air raid victims and bereaved families. The lawsuit, via news coverage and public awareness campaigns that included “Peace Walks” through Asakusa and signature-gathering drives at train stations in areas particularly affected by the March 10 firebombing, also heightened public awareness. At the handful of public meetings related to the lawsuit, hundreds of participants heard from not only plaintiffs and lawyers but from lawsuit supporters that included Tanaka Terumi, executive director of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organization, and Maeda Tetsuo, Tokyo representative of the Solidarity Committee for Chongqing Bombing Victims and a leading specialist on military affairs. This indicates how Tokyo air raid memory activists have formed important connections with groups involved in other redress activities and situated discussion of the Tokyo air raids in relation to Japan’s own air raids on Chinese cities and the general framework of the indiscriminate bombing of civilian populations.29

Barring a radical departure from precedent, the Tokyo High Court will almost certainly rule against the appeal currently before it. The energy being generated by the lawsuit, however, is also being directed toward a national movement that may have a greater chance of realizing its stated objective. On August 14, 2010, local citizens groups, bereaved family groups, and air raid survivors from 25 cities announced the creation of a Japan Air Raid Victim Liaison Committee (Zenkoku kushu higaisha renraku kyōgikai). Its main goal is to petition Japanese Diet members and municipal assemblies in cities affected by the 1945 air raids to support the creation of a financial relief law for air raid survivors and family members of victims, as well as to conduct an extensive survey of people killed in the air raids. Masuzoe Yōichi, during his 2007-2009 term as Minister of Labor, Health, and Welfare, stated that it was time to “deal decisively” with the issue of relief for air raid victims. Similar to the matter of compensating Korean and Chinese wartime forced laborers, the Japanese government under the leadership of the Democratic Party of Japan may prove to be amenable to actually taking up the issue if significantly pressured to do so.30 Attending the first Japan Air Raid Victim Liaison Committee was Sugiyama Chisako, who lost her left eye during an air raid on Nagoya and has labored without success since the 1970s to compel the government to pass a relief law. Reflecting the tenacity of air raid memory activists, the ninety-four year old, after telling reporters that the war has not ended for air raid sufferers, vowed not to die before the government passes such legislation.31

Recommended citation: Cary Karacas, Fire Bombings and Forgotten Civilians: The Lawsuit Seeking Compensation for Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids 焼夷弾空襲と忘れられた被災市民―東京大空襲犠牲者による損害賠償請求訴訟, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol 9, Issue 3 No 6, January 17, 2011.

See the following articles included in this special issue:

Bret Fisk and Cary Karacas, “The Firebombing of Tokyo and Its Legacy: Introduction 東京大空襲とその遺したもの−−序論”

Sumida Local Cultural Research Center of Taize, “That Unforgettable Day–The Great Tokyo Air Raid through Drawings あの日を忘れない・描かれた東京大空襲”

Bret Fisk, “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived 被災者が語る東京空襲”

Katsumoto Saotomo, “Reconciliation and Peace through Remembering History: Preserving the Memory of the Great Tokyo Air Raid 「歴史の記憶」から和解と平和へ東京大空襲を語りついで”

Yamabe Masahiko, “Thinking Now about the Great Tokyo Air Raid 今、東京大空襲を考える”

Articles on relevant subjects include:

Robert Jacobs, “24 Hours After Hiroshima: National Geographic Channel Takes Up the Bomb”

Asahi Shimbun, “The Great Tokyo Air Raid and the Bombing of Civilians in World War II”

Yuki Tanaka and Richard Falk, “The Atomic Bombing, The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and the Shimoda Case: Lessons for Anti-Nuclear Legal Movements”

Marilyn B. Young, “Bombing Civilians: An American Tradition”

Mark Selden, “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq”

Yuki Tanaka, “Indiscriminate Bombing and the Enola Gay Legacy”

Notes

1 Tōkyō Daikūshū Soshō Genkokudan, Tōkyō Daikūshū Sojō – Shazai Oyobi Songai Baishō Seikyū Jiken (Great Tokyo Air Raid Petition – A Case for an Apology and Damage Compensation), 2007, 113. At least two other air raid-related compensation cases appeared before this one. On legal technicalities, in 1980 the Tokyo District Court rejected a compensation lawsuit brought by an individual who experienced the March 10 1945 raid, as did the Supreme Court in 1987 with a suit filed by Nagoya air raid victims.

2 In March 2008, twenty additional plaintiffs, some affected by air raids on Tokyo other than the March 10 firebombing, joined the lawsuit.

3 “Sensō Higaisha to Mitomete,” Asahi shimbun, 10 March 2007.

4 Mark Selden, “A forgotten holocaust: U.S. bombing strategy, the destruction of Japanese cities, and the American way of war from the Pacific War to Iraq,” in Yuki Tanaka and Marilyn Young, eds., Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth Century History (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009, pp. 77-96). Tokyo air raid activists use the figure of 100,000 deaths in the March 10 raid, but believe that the actual death toll is higher. For a discussion of the difficulties of counting the dead, see Gordon Daniels, “The Great Tokyo Air Raid, 9-10 March 1945” in W.G. Beasley, ed., Modern Japan: Aspects of History, Literature and Society, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977, pp.113-131; Selden 2009; and Michael Sherry, The Rise of American Air Power: The Creation of Armageddon (New Haven: Yale University Press), p. 406, note 76.

5 For discussions of some of these compensation lawsuits, see, in addition to the many articles on forced labor by William Underwood in this journal: Robert Efird, 2008, “Japan’s ‘War Orphans’: Identification and State Responsibility,” The Journal of Japanese Studies 34.2 (2008), pp. 363-388; William Gao, “Overdue Redress: Surveying and Explaining the Shifting Japanese Jurisprudence on Victims’ Compensation Claims,” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 45 (2007), pp. 529-550; Petra Schmidt, “Japan’s Wartime Compensation: Forced Labour,” Asia-Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law 2 (2000), pp. 1-54; and Hae Bong Shin, “Compensation for Victims of Wartime Atrocities: Recent Developments in Japan’s Case Law,” Journal of International Criminal Justice 3 (2005), pp. 187-206.

6 The term was coined by historian Carol Gluck in “Operations of Memory: ‘Comfort Women’ and the World” in Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter, eds., Ruptured Histories: War and Memory in Post-Cold War Asia, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center, 2006, p.57.

7 Interview with Hoshino Hiroshi, 19 August 2009. For discussion of these terms, see Stephen Graham, ed., Cities, War, and Terrorism: Toward and Urban Geopolitics (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2004); and Kenneth Hewitt, “Place Annihilation: Area Bombing and the Fate of Urban Places,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 73.2 (1983), pp. 257-284.

8 Hoshino Hiroshi, “Tōkyō Kūshū, Kiroku Undō no Genzai,” (The Present Status of the Movement to Remember the Tokyo Air Raids), Rekishi Hyōron, 616 (2001), pp. 63-68; Semete Namae Dake Demo newsletter No. 13; 15 Jan 2006.

9 While city or local governments at other sites of catastrophic loss in Japan (most notably Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Okinawa, and Osaka) endeavored to compose such reports, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government did not until 2000.

10 Going through the reports brings to mind the spate of congratulatory messages cabled to Curtis LeMay, head of the XXIst Bomber Command, following the firebombing that killed the mother Haru, her children, and tens of thousands of others like them: “I am exceptionally pleased,” wrote, Army Air Forces chief of staff H.H. Arnold, closing with: “Good luck and good bombing.” Arnold’s top assistant, Lauris Norstad, expressed “the greatest admiration for the work you are doing,” and the commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s 58th Task Force wrote “may your targets always flame.” XXIst Bomber Command, Mission Report March 10, 1945, National Archives Record Group 18, Box 5446.

11 While we will never have an accurate figure of how many people died in the March 10, 1945 Great Tokyo Air Raid or for that matter in all of the air raids on Tokyo combined, a useful reference point when considering the 76,700 names of air raid victims that the city collected is the number of unidentified and unclaimed remains – 105,400 – that the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association (Tōkyō-to Irei Kyōkai) states are contained in a metropolitan charnel house. Hoshino 2001; Semete Namae Dake Demo newsletter Number 13, 15 January 2006.

12 One striking aspect of this monument as a receptacle for the names of the dead is that is closed to the public, and that even if an individual were allowed to enter the monument, the names of the dead, in closed books held behind a wall of glass, would not be visible. This is completely different, for instance, from how the names of the Osaka air raid victims are engraved in copper on a memorial, located outside the Peace Osaka museum, for all visitors to read and touch. The same holds true for Okinawa’s Cornerstone of Peace. For an analysis of the Tokyo air raid monument and the related movement to build a metropolitan peace museum, see Cary Karacas, “Place, Public Memory, and the Tokyo Air Raids,” Geographical Review, 100:4 (2010) pp. 521-537, found here.

13 Semete Namae Dake Demo newsletter Number 4, 15 August 2002; Number 6, 24 May 2003; Tōkyō-to Irei Kyōkai, Sensai Ōshisha Kaisō Jigyō Shimatsuki (A Complete Record of Steps Taken during the Reburial of the War Dead) (Tokyo: Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association, 1985).

14 Semete Namae Dake Demo newsletter Number 10, 15 February 2005, and Number 15, 10 September 2006.

15 The smell of burning flesh sickened even American B-29 crews flying 7,000 feet above the flames. See Chester Marshall, iSky Giants Over Japan: A Diary of a B-29 Combat Crew in WWII (Winona: Apollo Books, 1984), p. 147.

16 Tōkyō Daikūshū Sojō – Shazai oyobi songai baishō seikyū jiken.

17 For an extended analysis of the Tokyo air raid lawsuit and a related 1987 Nagoya air raid lawsuit, see Naitō Mitsuhiro, “Kūshū Higai to Kenpōteki Hoshō: Tōkyō Daikūshū Soshō ni Okeru Hisaisha Kyūsai no Kenpōron” (Air raid damages and legal compensation: A theory of constitutional compensation for victims in relation to the Great Tokyo Air Raid lawsuit), i, num. 106 (2009), pp. 1-51, found here.

18 Hewitt 1983, p.271.

19 With the court system usually assisting, the state has defended itself from most compensation lawsuits by foreign nationals with a handful of effective maneuvers: dismissing cases on technical grounds, the expiration of statute of limitations, the conclusion of state bilateral agreements, and an “irresponsibility of the state” doctrine that resists retroactively applying laws that obligate the state to compensate for losses incurred during the wartime period.

20 For detailed examinations of the applications of the endurance doctrine, see Robert Efird, “Japan’s ‘war orphans’: identification and state responsibility,” The Journal of Japanese Studies, 34. 2(2008), pp.363-388; and Akiko Naono, “Producing Sacrificial Subjects for the Nation,” in Herman Gray and Macarena Gomez-Barris, eds., Toward a Sociology of the Trace, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010, pp. 109-34.

21 Naono 2010.

22 Text of the 1942 Senji saigai hogo-hō.

23 Petra Schmidt, “Disabled Colonial Veterans of the Imperial Japanese Forces and the Right to Receive Social Benefits from Japan,” Sydney Law Review, 21 (1999), pp. 231-59, note 40; Ikeya Kōji, Robō no Kūshū Hisaisha: Sengo Hoshō no Kūhaku (Abandoned Air Raid Victims and the Absence of Postwar Compensation) (Tokyo: Kurieitibu Nijūichi, 2010). For a discussion veteran compensation laws, see Schmidt 1999.

24 Discussed in the Tokyo air raid lawsuit’s fifth oral proceeding, 24 April 2008.

25 Ikeya 2010.

26 Tokyo air raid lawsuit’s fourth oral proceeding, 21 January 2008.

27 These included the Economic Stabilization Agency’s 1949 Taiheiyō Sensō ni Yoru Wagakuni no Higai Sōgō Hōkokusho, (Overall Report of Damage Sustained by the Nation During the Pacific War, which can be viewed here); the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s 1953 Tōkyōto Sensai Shi, (A Record of War Damages in Tokyo); and the 1979 Zenkoku Sensai Shijitsu Chōsa Hōkokusho, (Survey Report of War Damages in Japan) released by the Japan Association for the Bereaved Families of War Dead (Nihon Sensai Izokukai) under the auspices of the Cabinet Secretariat.

28 Tokyo District Court 14 December 2009 ruling.

29 For example, see Maeda Tetsuo, Senryaku Bakugeki no Shisō: Gerunika, Jūkei, Hiroshima (Strategic Bombing Philosophy: Guernica, Chongquing, Hiroshima) (Tokyo: Gaifusha, 2006); and Sensō to Kūshū Mondai Kenkyūkai, eds., Jūkei Bakugeki to wa Nani Datta no ka. (What was the bombing of Chongqing about?) (Tokyo: Kōbunken, 2009).

30 William Underwood, “Redress Crossroads in Japan: Decisive Phase in Campaigns to Compensate Korean and Chinese Wartime Forced Laborers,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 30 No 1, July 26, 2010.

31 “Kūshū Hisaisha, Zenkoku Soshiki Kessei e – Kyūsai-hō no Seitei Motome,” Asahi shimbun, 13 July 2010; “Taisenchū no Kūshū Higaisha, Hatsu no Zenkoku Soshiki – Kyūsai-hō no Anbun Sakusei e,” Asahi shimbun, 15 August 2010.