Mount Fuji: Shield of War, Badge of Peace1

H. Byron Earhart

Invitation to Fuji

Mount Fuji2

The exquisite shape of Fuji, its symmetrical triangle dominating a broad plain, has delighted the Japanese for two millennia, and pleased Western eyes for several centuries. Unlike the manmade symbols of other countries––the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, and the pyramids of Egypt––this universally recognized sign for Japan is a natural landmark.

From its first mention in ancient Japanese poetry, this volcano became a mainstay of not only poetic and literary expression of diverse genres, but also of various graphic forms. Also, not unlike most peaks in the Japanese islands, it was esteemed as a sacred mountain, worthy of worship as a deity itself, or revered as the dwelling place of the divinities of Shinto, Buddhist, and Taoist origin. For most of its history, Fuji has been viewed as a physical, aesthetic, and spiritual phenomenon, but our focus here is on its appropriation as a clarion call for militarism and imperialism in World War II, and then in postwar times its transformation into a harbinger of peace and democracy.

In earlier days Fuji was one among many holy peaks, but in medieval times it eventually came to be seen by Japanese as the “number one” mountain of the known world of the three countries of India, China, and Japan. Two major factors led to an upgrading of Fuji’s importance. As political power shifted from the ancient capitals of Nara and Kyoto to the military rulers of Kamakura and Edo (Tokyo) in eastern Honshu, feudal lords and their retinues (and then merchants and common folk) traveled along the Tokaido (Eastern Sea Road). On this route they were treated to the lovely scenes, especially Fuji, later immortalized in Hiroshige’s woodblock depiction of Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido. In the mid-nineteenth century, as the country juggled the domestic problem of maintaining internal peace while warding off external threats from European and American powers, ideologues sought a symbol to emphasize the notion of “Japan” as a nation rather than as a group of individual feudal territories. Matters of aesthetics were part of the ongoing debate about Japanese identity. Some had favored the more Chinese style of monochrome painting to depict Fuji in a rather ethereal idealism, but the eighteenth century writer Hiraga Gennai insisted on a more empirical and realistic painting of the mountain. Convinced that the form of Fuji is identical with the concept of Japan as a nation, he argued for painting that could serve the national purpose.

The worldwide recognition of Fuji as an icon for Japan was made possible by the distribution of Hokusai’s and Hiroshige’s woodblock prints to Europe and America. By the time of Commodore Perry’s “opening” of Japan in 1852-1853, this snow-capped triangle was already famous in the West. The 1856 commemorative publication for Perry’s expedition pays tribute to the peak by placing its outline in the center of the embossed covers of the three volumes issued by Congress.

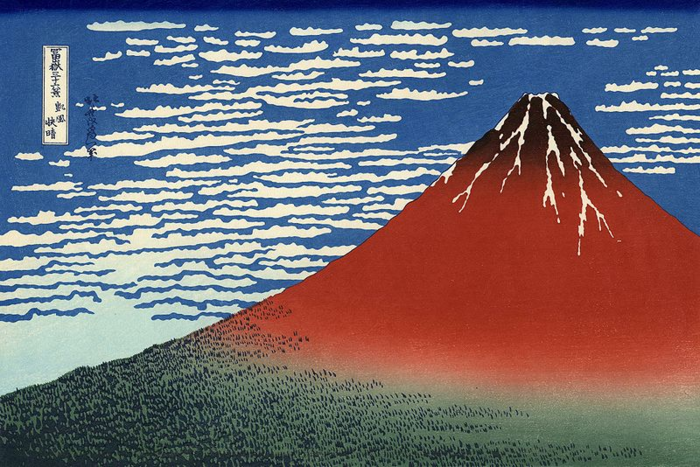

Hokusai, South Wind, Clear Sky (Red Fuji)3

The 1868 Meiji Restoration ended centuries of feudal rule and marked establishment of a new national government, also formalizing the shift of political power to Tokyo. The new government used the prestige of the emperor as the major symbol to forge identification with and allegiance to the national polity. Fuji was recruited for an important supporting role in this political drama in the transition to a unified country. The newly established national educational system included geography as a required subject; the study of Mount Fuji as a unique Japanese heritage was a key component of geography texts. Students read and composed poems about Fuji; viewed and drew pictures of the mountain, sang songs about it, and were encouraged to climb it. This symbol of the country also came to be used in the design of paper currency and coins as well as postage stamps.

Shield of War

Mount Fuji—the serene and lofty peak praised by generations of poets and artists, the sublime and sacred mountain that had inspired centuries of religious devotion––was, in effect, a ready-made symbol effective for unifying, motivating, and mobilizing the Japanese citizenry by 1931, when the Japanese army seized Manchuria and established Manchukuo, setting in motion a series of military advances into China and eventually plunging the Asia-Pacific region into a global war.

In 1938, when the government began publishing its own news magazines, Fuji was a stock feature both for the Japanese homefront and the colonies and occupied areas. A prime example of Fuji’s utilization in domestic propaganda is a photo in the October 1944 issue of the widely distributed government publication Shashin Shūhō (Photographic Weekly Report).4 Shot from a low angle with a serious-looking youth in the turret of a tank that dominates the picture, a diminutive Fuji is nestled in the lower left of the picture, in the same fashion as some of Hokusai’s everyday scenes.

Bantam Tank Troop5

A 1942 issue of the same magazine features the Bantam Tank Troop in a photograph titled “At the Foot of Mount Fuji”; the camera positions Fuji as the crowning touch over this phalanx of boys in outsize uniforms, in front of tanks. The synergy of such pictures goes far beyond what the text explicitly states: although Fuji is invoked as a guardian, at the same time, the images encourage and inspire the boy soldiers to guard and preserve not only this national hallmark, but also the nation as the physical land and political entity nuanced by Fuji. That this deeper message need not be spelled out speaks to the power of Fuji’s iconic status.

A more ambitious appropriation of the sacred peak’s cachet was the plan to make Fuji the emblem of the vast territory of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere that promised Asians relief from the colonial yoke of the European powers, simultaneously liberating these nations and uniting “one billion Asians” under Japanese leadership. One project in this grandiose plan was the Shōnan (Singapore) Express, a train that would run from Tokyo to Singapore, renamed as Shōnan (The Light of the South). A 1942 issue of Shashin Shūhō features a cover story of the proposed train route from Tokyo to Shimonoseki, on to Seoul, Mukden, Beijing, Canton, Hanoi, Saigon, Bangkok, and finally Singapore. A photograph of the proposed train at Tokyo station shows the “Fuji Express,” with a Mount Fuji-shaped emblem on the front of the locomotive.6 Although the Fuji emblem is difficult to make out in this wartime, low quality newsprint, the map clearly lays out the extensive pan-Asia route on which the Fuji Express was to travel––traversing Honshu and crossing the ocean, then passing through the major cities of the Asian continent. In effect, Fuji was selected as the logo-in-motion for the great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, and symbolic ambassador in Japan’s overseas propaganda campaign. The train, however, never made its transcontinental trek.

A 1944 cover of Shashin Shūhō has a photo of an Army Special Attack Forces (Kamikaze Forces) airplane tail with the outline of Fuji on it.7 This unit was the Fugaku (Fuji) Squadron. One description of the sendoff of these planes reads, “A man’s life is lighter than a feather, and the mission with which you are charged of destroying the enemy is heavier than Mount Fuji.”8 From early times Fuji was a favorite thematic subject in all of the decorative arts, including personal items such as combs and netsuke, as well as utilitarian items such as sword guards. One superb example of a seventeenth century “campaign coat” (jinbaori) emblazoned with Fuji survives, probably worn in battle, but behind the scenes. Apparently during World War II, Fuji’s power was employed as an offensive weapon for the first time.

The borders between propaganda, indoctrination, and persuasion are porous, and these techniques share a wide range of expressions. A postage stamp is a means of mailing, but some wartime issues definitely fall into the category of “propaganda.” In fact, an earlier standard English-language catalog of Japanese philately designates a special category of “Propaganda Stamps.” Among twelve such stamps, it notes: “The design of the 4 sen stamp shows peerless Fuji and that monumental tower which was erected in the province of Hyūga (Miyazaki prefecture), the legendary cradle of the ancestors of the Japanese Emperors.”9 The tower commemorates the legendary first Emperor of Japan, Jimmu Tennō. The 1942 stamp pairs the peak of Fuji and the top of the tower with the imperial chrysanthemum crest in a religio-political trinity of support for imperialistic ambitions and the war effort.

A group of stamps issued during Japan’s World War II occupation of the Philippines, pairs Fuji with a local volcano, Mount Mayon, in the service of Japanese power in the Philippines. A set of three 1943 stamps features two mountains: Mount Mayon, slightly lower to the right emerging out of a tropical setting of palm trees, and Fuji, to the left and a little above, resting on a layer of clouds. The setting is identified as “Philippine Islands,” but the twinning of Fuji with Mayon––Fuji in a slightly superior position––is reminiscent of the Japanese government’s use of Confucian ideology on the Asian continent to urge cooperation of subordinate “little brother” Asian countries with their “big brother” Japan. A 1943 issue of Shashin Shūhō includes an article that calls Mount Mayon “the Philippine Fuji,”10 a verbal move akin to European discoverers and American explorers planting the cross or a flag to “claim” a territory.

Fuji’s colonial service was not limited to the Philippines: “Eleven kinds of stamps were issued in May, 1943, by the Japanese Naval Administration in the Moluccas and Lesser Sunda.” One set of four includes a stamp featuring Fuji with the symbols of modern Indonesia. The image expresses even more vividly than the caption the dominance of Fuji in the upper half of the stamp, with the “sun-flag” in the middle, and the map of the East Indies at the bottom. Another colonial stamp of earlier date (issued by “‘Manchukuo’ Puppet Government”) is the 1935 set “Visit of Emperor to Japan,” here referring to Henri Pu-yi, the (puppet) emperor of Manchukuo. The stamp shows puffs of clouds over the steep slope of Fuji, described as “auspicious clouds on Fuji,” implying that Japan’s close relationship with Manchukuo boded well for Fuji/Japan.11 Conversely, Fuji seems to welcome––and authenticate––the puppet emperor of Manchukuo. The patriotic service performed by Fuji’s postal images of the 1930s and 1940s evokes the ideal of the late Tokugawa ideologues who insisted that pictures of the mountain should be “tools of national utility.” Fuji certainly functioned as an instrument of imperial, colonial, and military goals, both within Japan and in the colonies.

Two Japanese wartime cartoons demonstrate how the image of Fuji was borrowed to promote the war; they contain the gist of the Japanese homefront mission of mocking the enemy and supporting the just cause of the war. One is a pictorial depicting Roosevelt and Churchill as debauched ogres drinking and partying within sight of Mount Fuji, with American military forces advancing over the globe toward the sacred peak, which rises majestically above the horizon and touches the top of the picture. The left side with the two Allied leaders has ominous dark clouds, but Fuji’s triangle is pure white: the morality play of Japan and purity is contrasted with the dark, sinister Allied leaders and their troops. In another cartoon in a 1944 Japanese popular magazine, an American is trying to lasso Mount Fuji, but is thwarted by the righteous bayonet of “the divine country Japan” that spears the American in the posterior.”12

Mount Fuji Across the Pacific

A remarkable parallel of the Japanese and American propaganda campaigns is that Fuji played a similar role on both sides of the Pacific, serving as a convenient sign for Japan as well as its people and government. An American newspaper cartoon published during the 1942-1943 Japanese occupation of two of the Aleutian Islands presents an interesting foil to the Japanese cartoon of the carousing ogres Roosevelt and Churchill overseeing the attack of Allied forces on Mount Fuji. In the American cartoon the viewpoint is reversed, with an apish Japanese soldier poised on the end of a long diving board that has “The Aleutians” printed on the end. The point of the cartoon is spelled out in its title: “Knock him off that springboard.” A tiny smoking Fuji and a miniature torii (sacred archway) identify the landmass of Japan anchoring that springboard.13 A significant contrast in the Japanese and American graphics is that on the Japanese side a lofty Fuji is positioned from mid-ground to the top; in the American cartoon, Fuji is a small and roughly drawn prop. But on both sides of the Pacific, no explanation is needed to convey the message that Fuji stands for Japan.

“Mom and Fuji”14

American military propaganda (referred to by practitioners as psychological warfare) was quite active during WWII, with 400,000,000 leaflets of propaganda dropped behind enemy lines in the Southwest Pacific. Under the tutelage of American social scientists, these “psywar” agents deliberately avoided criticism of the emperor to avoid antagonizing Japanese readers, blaming the war instead on the militarists (gunbatsu). Fuji, however, was fair game, and was used both as a carrot and a stick. Leaflets portrayed Fuji as a nostalgia-marker to convince starving and ill-equipped Japanese soldiers on Pacific isles to give up the fight and return to their homeland. One leaflet combines the theme of homesickness with fear, a picture set against the backdrop of cherry blossoms and Fuji, with a Japanese mother and child in the forefront, and dead Japanese soldiers behind this pair. Americans have joked that WWII GIs fought for the homespun values of “mom and apple pie.” This leaflet seems to appeal to the Japanese values of “mom and Fuji.” The same picture (probably a photo montage) was used on other leaflets with several texts calling on Japanese soldiers not to waste their lives in battle or suicide, but to return to the homeland, which was being destroyed by the war. The equating of Fuji and homeland is clear.

Mirror Image of Fuji15

Two other American propaganda leaflets utilize a photograph and a woodblock print of Fuji to invoke homesickness. In leaflet 101, the camera captures the triangle of Fuji reflected on a nearby lake, a favorite tourist shot. The back of the leaflet makes clear that “Its purpose was to stir up pangs of homesickness and resentment toward their leaders in Japanese troops who are about to be attacked by American forces.”16 The full text of this leaflet reads:

Now is the season of beauty in your homeland and the glorious snow-capped peak of Mount Fuji beckons to the traveler and the visitor. Your parents and wives await you and your dear children wonder whether they will ever see you again.

But you are here on a miserable island, awaiting our overwhelming force of men and machines. Your military leaders grow fat at home as they continue to mislead your people. They enjoy the beauties of the season and the thrilling sight of Mount Fuji. Their children eat with them and bask in their love.17

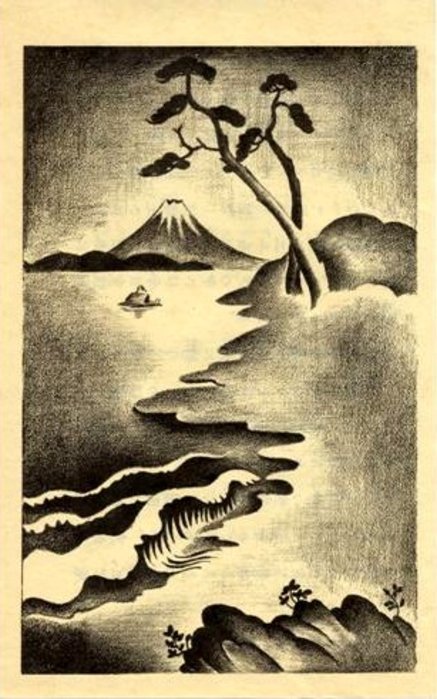

Traditional Print18

A leaflet in the style of a traditional print, a rather sentimental landscape, is leaflet 520. The picture features a stereotypical arrangement of rock, beach, waves, ocean, and two curved pines framing a distant Fuji. The text on the back of the leaflet, although not explicitly mentioning Fuji, parlays emotional attachment to the peak to criticize the military leadership and encourage soldiers to return to their homeland.

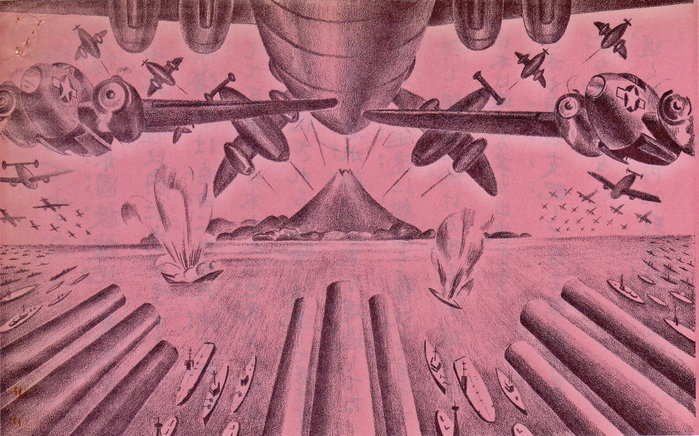

Bombardment of Fuji19

The sacred mountain was actually “targeted” by another American leaflet. Late in the war, when American planes were regularly bombing Japan, the “psywarriors” printed and dropped single sheets with the triangular peak prominent in the center, like a bull’s-eye. The lower third of the picture is a formation of battleship guns and ships pointing at Fuji; the upper third of the leaflet is the underside of a large four-engine bomber, flanked by a number of twin-engine bombers all headed toward Fuji, with two bombers returning from their sortie. Here the mountain is a visual rubric for Japan, the recipient of unrelenting air and naval bombardment, intended to invoke fear, despair, and surrender.

Fuji Pilgrim20

One of the most intriguing American leaflets is a portrayal of Fuji in its religious and ethical dimensions to turn the mind of the fighter away from the war toward traditional values. A tasteful dark blue and white broadsheet depicts a Japanese pilgrim standing at the foot of Fuji at the intersection of two paths marked by road-stones reading “Duty” and “Humanity”. The text on the leaflets states, “There are two roads but only one goal,” cajoling the soldier to serve family, emperor, and country by giving up on a war started by the militarists. The pilgrim in traditional outfit is flanked by the two road-stones, aligned with the peak of Fuji, and facing the summit as his “goal.” From each of the stone posts a ribbon of road winds up each side of the image toward the slopes of the mountain. The leaflet shows some acquaintance with the notion of Fuji as a sacred mountain, using the theme of climbing Fuji as an act of pilgrimage linked to personal, social, and national values.

The American psywarriors utilized Fuji as both sign and symbol for subtle invocation of emotions linked to homeland and duty. Japan’s sacred mountain played a double agent role in World War II, recruited for service in both Japanese and American propaganda.

Badge of Peace

In the postwar purging and reform administered by the US-led occupation forces, the symbol of Fuji remained intact, yet temporarily hidden from public view. By order of the Occupation censors within SCAP (the Supreme Command of the Allied Powers), Japanese filmmakers were not allowed to show Fuji. This prohibition, like a number of arbitrary decisions of the occupying authorities, was not without its self-contradictions. One film director, Makino Masahiro, who in 1946 was prevented by the censors from including scenes of Mount Fuji in his film Sophisticated Wanderer (Ikina furaibo), objected, arguing that the storyline was about cultivating land on the slopes of Fuji, and the film could not be completed without including the mountain. He claimed that Fuji was a symbol not of nationalism, but of the Japanese people. Frustrated by the persistent refusal of the authorities to allow shots of the mountain in the film, Makino asked them if they had really believed Fuji was a symbolism of nationalism, why hadn’t they dropped the atomic bomb on Fuji instead of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Makino’s question was rhetorical, but some commentators claim that the U.S. military did entertain the possibility of dropping the atomic bomb on Fuji in order to set off its natural volcanic forces. And a visit to various websites yields such suggestions across the political spectrum: the humanitarian voices write that it would have meant less loss of human life to bomb Fuji; the more vindictive argue that it would have served Japan right to lose its hallmark.

The Occupation’s rejection of Makino’s film presents a double, or even quadruple irony, because this was not the first time a Fuji film was blocked. The left-wing antiwar director Kamei Fumio, who in 1941 proposed a script for The Geology of Mt. Fuji (Fuji no chijitsu), was turned down by Japanese authorities because its rational, scientific analysis angered the government, which was promoting the mystique of Fuji as a national symbol.21 Wartime Japanese censorship blocked a film about Fuji because it was merely natural and therefore not imbued with mystical nationalism; postwar American censorship banished the mountain from the screen because even a “natural” scenario of farming on the peak’s slope was presumed to be nationalistic.

New Year’s Editorial22

If Fuji was excluded from films during the Occupation, it was not blackballed from other media. A photograph of the mountain was used to drive home a front-page 1946 New Year’s editorial of the Nippon Times, which announced the end of imperialism and looked forward to “the coming of Democracy and the Four Freedoms promised in the Atlantic Charter. The glistening peak of Mt. Fuji, the blue shadows of the pine mottled with whiteness, reflect a peacefulness that augurs well for the future….” In less than half a year, Fuji had been transformed from the shield of war to a badge of peace.

Another instance of the postwar “pacification” of Fuji’s image took place in postage stamps. In 1946 the government reissued a stamp featuring Yasukuni Shrine, the Shinto shrine where war dead are memorialized. An important symbol of emperor and war, to this day Yasukuni remains a controversial institution emblematic of the legitimacy and nobility of the emperor, the Japanese empire, and the Pacific War. The Occupation Forces insisted that the Yasukuni stamp be withdrawn. By contrast, “Postwar efforts at postage stamp making in Japan were marked by the implementation of a program for revising designs so as to symbolize a country out for peace. The first step toward the attainment of this avowed object was the issuance on August 1, 1946 of a stamp… [whose] design is taken from the ‘Shower at the Foot of Mt. Fuji,’ one of the masterpieces of Hokusai….”23 The heritage of the sacred/beautiful peak reemerged to trump its military/imperialistic record of service.

Not all Westerners were favorably inclined toward the sacred mountain as a harbinger of democracy. A postwar newspaper cartoon from the Detroit News portrays Fuji not as the voluntary bearer of, but the involuntary recipient of, democracy. This cartoon is dominated on the left side by an American GI who holds open a book, Democratic Way of Life, forcefully admonishing with his index finger in the face of a much shorter Japanese man holding a scabbarded sword with one hand, an offered flower in the other.24 The right side of the cartoon is a grab bag of Japanalia, crowned by snow-covered Fuji. Here the moral is that all of Japan, including Fuji, needs the American lesson of democracy.

USARJ Insignia

The ultimate irony in Fuji’s postwar trajectory is the fact that this image, temporarily banned by Occupation censors for its association with Japanese nationalism and militarism, soon became the design of choice for representing a united Japanese and American national and military effort. The American military presence in postwar Japan embraced Fuji, even adopting it as part of their official regalia. A prime example of these “Fujified” American military emblems is spelled out by an official website providing a history of “The United States Army Japan”: “The Distinctive Unit Insignia… for USARJ is a gold color metal and enamel device… consisting of a stylized representation of Mount Fuji in light blue, with a white peak silhouetted against a red demi-sun on a blue background…. The location of USARJ in Japan is symbolized by the representation of Mount Fuji, a world famous symbol of Japan.”25

Comsubgru Seven Cap

Other American military groups in Japan have been represented in some form with the shape of Fuji. The Command Submarine Group Seven, the American submarine group stationed at Yokosuka, Japan, has a cap (and various other accessories) with a badge featuring a light blue Fuji in the background, a red Shinto torii (sacred archway) in the middle ground, and in the foreground a submarine flanked by two dolphins.26 Fuji also appears on a number of postwar American military coins in Japan, representing the army, navy, air force, coast guard, and marines.27

U.S. Army Challenge Coin

These American military symbols harken back to Commodore Perry’s mid-nineteenth century memorial volumes, a major vehicle for introducing Japan to the U.S. and the Western world, which had the outline of Fuji embossed on their cover––suggesting American domination over Fuji and Japan. In similar fashion, the adoption of Fuji by the U.S. military may also be seen as the “capture” of one of Japan’s preeminent symbols. This brings to mind the Japanese wartime propaganda depicting “the cartoon-thug America” who “tried to lasso Mount Fuji.” One of Japan’s worst wartime fears was realized in peacetime: Fuji became a trophy of the victorious Americans.

The notion of Fuji as military trophy has wartime precedents. Several of the most dramatic American wartime pictures of Fuji show the mountain “captured” by the camera through American submarine periscopes. Winston Churchill in his history of the war selected one such submarine photo of Fuji, pairing it with a photograph of a Japanese ship that has been torpedoed and is sinking.

Crews of various submarines brag about coming close enough to the Japanese homeland to photograph Fuji. The website for the submarine Icefish makes such a claim for their commander: “His daring proximity to the coast of Japan was documented by his famous photograph, published on the cover of Life magazine, of Mount Fuji, taken through the periscope of his submarine.”28 The braggadocio of these accounts resembles the “counting of coup” by Native Americans, who strove to strike or touch their enemy, and thereby display their own courage while robbing the power of the adversary. Here the derring-do of the sub commanders was to approach and seize the hallmark of Japan through photography.

Such an adventurous challenge could not escape the attention of Hollywood. The periscope “capture” of Fuji was dramatized in the 1943 Warner film Destination Tokyo, which featured Cary Grant. The mostly fictional account has an American submarine land in Tokyo Bay to prepare for Doolittle’s 1942 bombing of Tokyo. In the movie, when the periscope is raised to confirm their position, a huge Fuji appears right in front of them (as the soundtrack rises to a crescendo). This film uses Fuji as a marker for Japan both viewed through the periscope and from the deck of the submarine as a landing party goes ashore, and also in a brief aerial shot when Doolittle’s planes begin their bombing run on Tokyo.

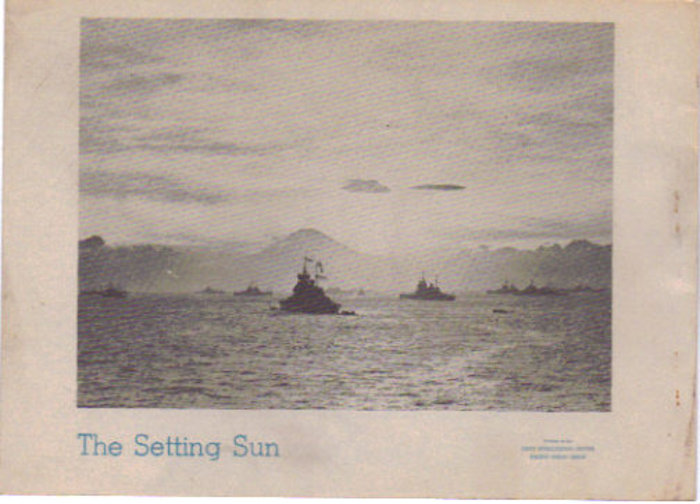

“The Setting Sun”

The most powerful symbolic use of Fuji to depict simultaneously the defeat of Japan and the capture of the mountain was at the surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay, with Fuji as a backdrop. An eight-page brochure issued by “Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Areas” titled “U.S.S. Missouri: Scene of Japanese Surrender,” was originally distributed to Naval personnel shortly after the surrender in 1945.29 The brochure consists mainly of postcard-size photographs, featuring an aerial shot of the Missouri, and the American and Japanese signatories of the surrender. The back of the pamphlet, titled “The Setting Sun,” shows the U.S. fleet anchored in Tokyo Bay, with the sun setting over the silhouette of Fuji, a fitting end to “the rising sun” (Japan). The picture vividly recalls the imagery of Commodore Perry’s 1856 commemorative volume with the American fleet dominating Tokyo Bay and Fuji, conveying the message that America has again dominated Japan, as symbolized by Fuji.

In 1953, the U.S. Post Office issued a stamp commemorating the hundredth anniversary of the opening of Japan by Perry in 1853. The timing of this stamp is significant also for being released just a year after the end of the 1945-1952 Occupation of Japan. The design of the stamp incorporated the anchorage of American warships in Tokyo Bay and a portrait of Perry, with Fuji in the center and a samurai in the lower right.

Commodore Perry Commemorative Stamp30

These are the same elements found embossed on the official reports of Perry’s Japan mission.

Exoticism, Eroticism, and Nationalism

Six decades after the end of World War II, scholars and politicians still argue about the causes of the war and the actions and intentions of the military and governmental leaders on both sides. What has happened to Fuji during this time? The sacred peak has continued to lose some of its sacrosanct aura, climbed by hundreds of thousands of Japanese and Western tourists, and only handfuls of traditional pilgrims. The exoticism of Fuji––seen so frequently in woodblock prints and borrowed so freely and forcefully by van Gogh and other Impressionists, while touted by literary figures such as Lafcadio Hearn, as well as many travelers––thrives, although success has its own perils. From the time of the economic miracle in Japan during the 1960s and 1970s, a veritable flood of stamps featuring Fuji was released by many countries. Fuji’s image has been replicated on almost every conceivable form of consumer goods––from toilet paper to drinking water––and in the United States as a name for Japanese restaurants (many of whose owners and staff are not Japanese).

A lesser-known aspect of Fuji’s heritage has been its erotic undertones––a medieval travel book likened Fuji’s eruptions to “sexual effervescence.” In 1950s America, Wanda Jackson, a contemporary and acquaintance of Elvis Presley, made famous the rockabilly tune “Fujiyama Mama,” which belted out the sexual innuendo of a Fujiyama mama who has been to Nagasaki and Hiroshima and can “do the same” to her lover, because she’s about to blow her top. Her tour of Japan and performance of this song was a smash hit. The author has seen at least one instance of a “Fuji Massage Parlor,” which utilizes “Fuji” as a synonym for “Asian” and draws on GI familiarity with the yellow-skinned sex trade.

The patriotic/nationalistic nuances of Fuji have been much more subdued since 1945. Two notable exceptions are the poet Kusano Shinpei and the painter Yokoyama Taikan. As young men in the early decades of the twentieth century, each spent considerable time outside Japan––Kusano in China, Yokoyama in India—in various “Pan-Asian” ventures before returning to Japan with renewed nationalistic and ultra-nationalistic views. Kusano returned to China in 1940 as an adviser to the puppet government established by the Japanese. He linked Fuji with China’s mythical mountain Kunlun in a 1943 poem––the same year as the release of the Philippine occupation postage stamp equating Fuji and Mount Mayon. In a 1968 poem he declared that Fuji is not a sacred mountain, it is just a mountain––“Just a mountain but the symbolic existence of Japan.”31

Yokoyama, who traveled to India in the first decade of the twentieth century, was active in the form of traditional Japanese painting (Nihonga). Shortly before World War II, with his mentor Okakura Kakuzō he welcomed to Japan the Nobel literature laureate Rabindranath Tagore––until Tagore criticized Japanese militarism. Yokoyama was a staunch supporter of Japanese expansionism across Asia, and personally contributed large sums for fighter planes. Like Kusano, after the war Yokoyama remained an unreconstructed nationalist. Kusano’s 1952 sketches for a painting Pacific Ocean on a Specific Day (Aru hi no Taiheiyo) reveal his intense patriotism. These views of Mount Fuji “looming serenely over wildly turbulent waves” have been interpreted as “a major statement about war and nationhood… an allegory of Japan’s emergence from… World War II.”32

Spiritualism, exoticism, eroticism, nationalism, imperialism, orientalism, reverse orientalism, pacifism, neo-nationalism––how could one mountain represent all of these modalities? The wartime and postwar episodes of Fuji’s exploitation, by both Japanese and Allied forces, present a sobering lesson of how culture can be made to serve war and pacification. Perhaps the true test of an icon is its ability to be flexible, malleable, and adaptable to multiple human situations and historical circumstances. Fuji has passed this test with flying colors.

No one can predict the next eruption of Fuji. But like the truncation of Mount St. Helens, or the catastrophic earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011 near Sendai, a cataclysmic event could occur, radically altering or even obliterating the perfect geometrical form of the mountain, leaving behind a wealth of aesthetic and spiritual conceptions without an earthly counterpart. Some Japanese and non-Japanese aficionados of Fuji have begun work to have the mountain recognized as a World Heritage Site, in order to preserve this cultural, environmental, and aesthetic legacy for future generations. Whatever the outcome, we share the optimistic view of the poet Kusano that people will still look back at Fuji “as a symbol of particular beauty,” and that “a large number of different works about Fuji [will] be created in the future.”33

H. Byron Earhart, Professor Emeritus of Comparative Religion at Western Michigan University, author of textbooks and monographs on Japanese religion, now resides in San Diego. His book, Mount Fuji: Icon of Japan is now available from the University of South Carolina Press. His next book is a comparative study of amulets, talismans, and fetishes.

Recommended citation: H. Byron Earhart, Mount Fuji: Shield of War, Badge of Peace, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 20 No 1, May 16, 2011.

Notes

1 This article is excerpted, with permission, from the author’s forthcoming book, Mount Fuji: Icon of Japan, with University of South Carolina Press. The book contains illustrations not in the article, which includes more images related to Fuji’s role in war and peace. Special thanks to my son David C. Earhart for help with materials for the article, to my wife Virginia M. Earhart for assistance with the images, to Mike Sirota for editing the text, and to Mark Selden for editing the article for Japan Focus.

2 This photograph is from the psywarrior.com website, the listing “OWI Pacific Psyop Six Decades Ago,” with thanks to Herbert Friedman.

3 This print is from Wikimedia Commons, accessed April 28, 2011.

4 Hereafter cited as PWR. See PWR 34, 4 October 1944 (cover); see also this photo in David C. Earhart, Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media, p. 210, illustration no. 54.

5 This photo is from PWR 246, 11 November 1942, p. 17. Thanks to David C. Earhart for providing this image, courtesy of his Collection of Japanese Primary Sources from the Pacific War.

6 PWR 242, 14 October 1942, pp. 12-13; see this photo in David C. Earhart, Certain Victory, p. 291, illustration no. 79.

7 PWR 346, 29 November 1944 (cover); see this photo in David C. Earhart, Certain Victory, p. 440, illustration no. 51.

8 Dennis Warner and Peggy Warner, The Sacred Warriors: Japan’s Suicide Legions, p. 123.

9 Yokichi Yamamoto, Japanese Postage Stamps, pp. 68-69.

10 PWR 266, 7 April 1943, p. 17; see David C. Earhart, Certain Victory, p. 289, illustration no. 74.

11 Sakura Catalog of Japanese Stamps, pp. 216-221, 296-297.

12 John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War, pp. 195, 249. For another Japanese cartoon caricaturing Roosevelt and Churchill, see this link.

13 Dower, War Without Mercy, p. 184.

14 Psychological warfare leaflets from World War II, dropped from airplanes on Japanese civilians and military personnel, have been collected and described on the psywarrior.com website. Special thanks go to retired United States Army Sergeant Major Herbert Friedman, an expert on U. S. psychological operations, for locating and granting permission to reproduce images of Fuji on American propaganda leaflets. Leaflets are identified by the number on the psywarrior.com website, the listing “OWI Pacific Psyop Six Decades Ago.” Hereafter cited as “OWI.” Illustration 3 is leaflet 114a on this website. Friedman includes in “OWI” a brief section, “Mount Fuji as a Pictorial Theme of American Psyop,” to which the present author contributed.

15 This image is leaflet 101 from Friedman, “OWI.”

16 Friedman, “OWI.”

17 Friedman, “OWI,” Leaflet 101. Translation from Japanese is quoted from the website.

18 This image is leaflet 520 from Friedman, “OWI.”

19 This image is leaflet 519 from Friedman, “OWI.”

20 This image is leaflet 2064 from Friedman, “OWI.” The translations from Japanese are quoted from the website.

21 This account is adapted from Takakuni Hirano, Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema under the American Occupation, pp.104-145.

22 Nippon Times, January 4, 1946, p. 1. Thanks to David C. Earhart for providing this image, courtesy of his Collection of Japanese Primary Sources from the Pacific War.

23 Yamamoto, p. 76.

24 Dower, “Discussion,” in The Occupation of Japan: Arts and Culture, p. 121.

25 From “History of the US Army in Japan,” on an earlier website. A more recent website, does not include this historical account, but shows the distinctive insignia as in illustration 9, as well as a Fuji shoulder patch, and a challenge coin with Fuji. For a published source, see Barry Jason Stein and Peter Joseph Capelotti, U.S. Army Heraldic Crests, p. 411. Thanks to David C. Earhart for the gift of this insignia.

26 Thanks to Kenneth C. Earhart for the gift of this cap.

27 Four of these “challenge coins,” each with a different design including Fuji, are in the author’s personal collection, purchased on ebay.

28 See this link. Last accessed April 28, 2011.

29 Gift of the author’s father, Kenneth C. Earhart, who received it when stationed on the USS Missouri at the time of surrender.

30 This stamp is from Wikimedia Commons, accessed April 28, 2011.

31 Kusano Shinpei, Mt. Fuji: Selected Poems 1943-1986, p. 33.

32 John M. Rosenfield, “Nihonga and Its Resistance to ‘the Scorching Drought of Modern Vulgarity,’” p.174.

33 Kusano Shinpei, in Leith Morton, 1985. “A Dragon Rising: Kusano Shinpei’s Poetic Vision of Mt Fuji,” Oriental Society of Australia, (1985) 17: p. 53.